Archive for the 'Books' Category

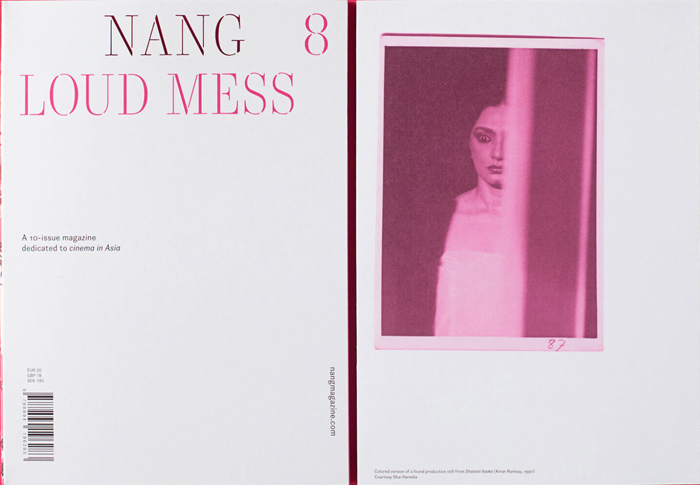

An elegant path into modern Asian cinema

DB here:

Nang is an anomaly in today’s film culture. A limited-edition magazine published only in hard copy, it carries no advertising, film reviews, or festival reports. It’s printed on exquisite, environmentally-sensitive paper, with binding that allows it to open and stay flat. It radiates casual elegance, and it’s devoted to modern Asian filmmaking. A preface explains:

Thanks to a unique group of guest editors and contributors, Nang broadens the horizons of what the moving image is in Asia, engaging its readers with a wide range of stories, contexts, subjects and works connected by the cinema.

This sounds fairly conventional, but Nang’s mission is also “to expand (the idea of) what a cinema magazine can be today.” This ambitious goal comes from this remarkable declaration of principles by Publisher and Editor-in-Chief Davide Cazzaro. He reveals Nang’s deep commitment to analog publishing and to quality, highly diversified content.

Cazzaro’s statement only hints at the riches within every issue.There are historical studies, such as Debrashree Mukherjee’s article on female barristers in Mumbai cinema and Chew Tee Pao’s account of archiving the Singapore feature Medium Rare. Experts such as Aaron Gerow, Jasper Sharp, Sam Ho, Victor Fan, Noel Vera, Darcy Paquet, Mark Schilling, and Goran Topalovic offer incisive, in-depth pieces. But this is no musty academic journal. There are cartoons, paintings, collages, and other forms of graphic art. There are poems and short stories as well: issue no. 3 is devoted to fiction.

Nang is passionately dedicated to honoring and understanding the creative process of filmmakers. Given my proclivities, I remain in awe of issue no. 5,”Inspiration,” which includes writings by and interviews with Mira Nair, John Woo, Jia Zhangke, Hou Hsiao-hsien, Tsui Hark, and many other directors. Me being me, I was especially keen to find out the Nair planned Monsoon Wedding by laying out “a sea of index cards” on her bed to keep the plot lines balanced.

No less revelatory is no. 6, “Manifestos,” which include previously untranslated manifestos from modern Asian film movements. There are documents from Taiwan, Indonesia, South Korea, India (Satayajit Ray, Ritwik Ghatak), the Philippines, and many other locales. There’s even serious consideration given to Kim Jong Il II’s 1973 On the Art of the Cinema, an effort by the North Korean dictator to specify the demands of a communist cinema. Each entry is graced by photos of hands cradling rocks.

Other issue topics are less clear-cut. “The Scent of Boys” is largely devoted to same-sex cinemas, but through an unusual route: writers were asked to reflect the sensory and sensual aspects of bodies and their interactions on the screen. Critics, historians, and filmmakers reflect on figures and films that have shaped their sensibilities. Issue no. 8, “Loud Mess,” is about “the power of transgression” in many dimensions–horror, eroticism, sound.

I really can’t do justice to the splendors on display in Nang. Go to the Blog page for a potpourri of articles and background on the editors. One concession to the digital realm: A ten-year look back at Nang. Most back issues are still available; go here to see the possibilities and browse some pages. Bargain-priced too, considering that these are in effect art books. But hurry: issue no. 9 is already out, and the next one is said to be the last.

Nang is an energetic, imaginative effort to open up new aspects of Asian filmmaking. Davide Cazzaro and his guest editors have given us a true labor of love–obviously, their love of Asian cinema, but also an acknowledgment of what many of us feel: This is one of the world’s greatest film traditions.

Thanks to Goran Topalovic for calling my attention to Nang and Davide Cazzaro for providing me sample issues!

An update about our blog

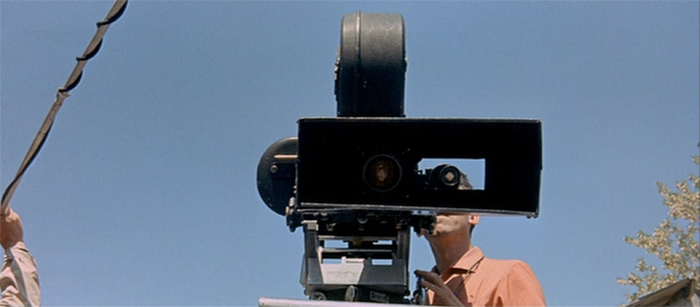

Contempt (Le Mépris, 1963).

DB here:

After fifteen years of fairly steady blogging, we suspended putting up new entries in early October. We were reluctant to go into explanations of a fluid situation, but now things are stable enough for us to set out what happened.

I had surgery for oral cancer in July and August, followed by brief hospital stays. My doctors, all excellent, have said and continue to say that my prognosis for recovery is good. After a hiatus of rest at home, when I posted two blogs, I went in for radiation treatments and chemotherapy. This process took six weeks and has left me very tired, while also dealing with side effects of the treatments and medications.

Since then, I simply have lacked the energy and concentration to write anything new. I try to find time for clerical cleanup work on my book manuscript, Perplexing Plots: Popular Storytelling and the Poetics of Murder. The plan is to submit it for production in March at Columbia University Press.

But Kristin, who has been devotedly taking care of me, and I now have a routine that should permit at least occasional blogging. She will of course provide her annual list of Best Films of the Year for 90 Years Ago, and she has some other ideas. I hope as well to offer something, though naps and streaming always seem to obtrude.

In some ways, there are a couple of substitutes for my blogging–both courtesy of Criterion. One is my video essay on Johnnie To Kei-fung’s Throw Down, “Hidden in Plain Sight.” A look at the movie’s characteristic narrative and stylistic strategies, it’s available on both the Channel and the blu-ray release. I’m grateful to Curtis Tsui, the producer, for asking me to do it; I now appreciate the film a lot more. The other bonus materials are extremely informative as well. If you haven’t seen Throw Down, what are you waiting for?

Before I went into surgery, I recorded two linked installments of our “Observations on Film Art” series. Both concern Godard’s use of aspect ratios. The first, on Vivre sa Vie, is available here. The second, on Le Mépris/Contempt, is here. I try to show how Godard exploits the differences between 4:3 proportions and the anamorphic widescreen format. (In a way, they balance the exploration of Godard’s late-career use of aspect ratios, seen in this blog entry.)

Kristin and Jeff Smith weren’t idle during our hiatus. The Channel released her analysis of the road motif in Pather Panchali and Jeff’s study of Agnès Varda’s editing in Le Bonheur. More installments are planned, of course. We appreciate our loyal viewers who have stuck with us through 45 episodes!

During my confinement, the books have kept arriving on our doorstep, and many deserve notice. I’d be remiss, though, if I didn’t call your attention to a couple of my favorites. One is J. J. Murphy’s monograph on The Florida Project. This in-depth exploration of Sean Baker’s creative process and the contributions of many collaborators is timely, given the release of Red Rocket. Besides, how many authors get the director they wrote about to do PR for them?

The other book is a magnificent contribution to our understanding of cinema: James E. Cutting’s The Movies on Our Minds: The Evolution of Cinematic Engagement. It offers a history of popular films from the standpoint of psychological engagement of the spectator. It shows “how they are structured, and how that structure has been crafted by a century’s worth of filmmakers to affect our minds.” Using Big Data (hundreds of films) and fine-grained analysis of cuts, lighting, and other techniques, James brings in evidence from empirical psychology to show that filmmakers are, as we’ve long known, “practical psychologists.” Beautifully designed with color illustrations, written in a conversational style, it’s destined to be a classic. I hope to blog about James’ book more at length when stamina returns.

It’s been heartening to see that we still get many pageloads every day; some of our efforts seem to endure. In addition, my colleagues here and elsewhere have been wonderfully kind in offering their support during these days. There are still months to go, but Kristin and I remain confident.

Contempt (Le Mépris, 1963).

Crime in the streets and on the page

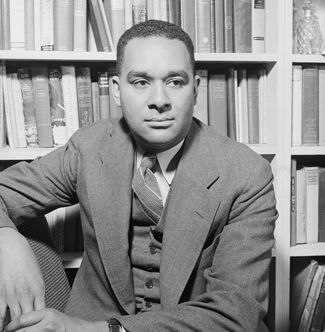

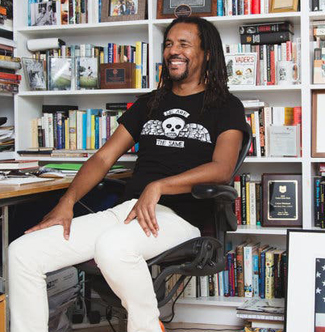

Richard Wright (Britannica.com); Colson Whitehead (New York Times).

DB here:

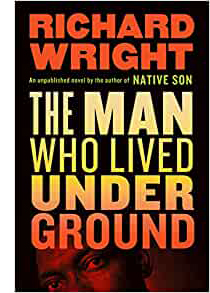

In the 1940s, Richard Wright was one of America’s most distinguished writers. His shocking novel Native Son (1940), in which a young Black man kills and decapitates a white woman, became a best-seller. After Citizen Kane, Orson Welles mounted a flamboyant Broadway version. Wright’s memoir Black Boy (1945) was a milestone in depicting the experience of a modern African American migrating from the South to Chicago. Yet a book Wright wrote between these two failed to find a publisher and has only recently been revealed.

The Man Who Lived Underground was inspired by a report about a Los Angeles burglar who launched his missions from a bunker in the sewer system. In Wright’s book, this Underground Man is Fred Daniels, a Black laborer who’s been arrested for a murder he didn’t commit. The police torture Fred into making a confession. But when Fred is allowed to accompany his pregnant wife to the hospital, he escapes into the sewers.

There follows an extraordinary adventure in exploring city life literally from below. Fred builds himself a sanctuary and begins to survey, in a cross-sectional panopticon, the lower depths of churches, movie theatres, markets, furnace rooms, and office buildings. As he grows more confident, he pillages food, furniture, and money, decorating his man-cave with dollar bills and jewels. But he also has an urge to return to the world above, if only to show what a free Black man can do.

There follows an extraordinary adventure in exploring city life literally from below. Fred builds himself a sanctuary and begins to survey, in a cross-sectional panopticon, the lower depths of churches, movie theatres, markets, furnace rooms, and office buildings. As he grows more confident, he pillages food, furniture, and money, decorating his man-cave with dollar bills and jewels. But he also has an urge to return to the world above, if only to show what a free Black man can do.

Why Wright’s manuscript was rejected is unclear. His agent and his customary publisher Harper left notes suggesting that the more symbolic, hallucinatory dimensions of the book didn’t blend with its social realism. One reader thought that the portrayal of Fred’s beating by the police was “unbearable.” That might refer to the harsh violence of the scenes, but also because Wright shows something seldom acknowledged, then or now: the routine, sadistic police brutality directed at Black citizens.

In any event, Wright set the book aside, but he did turn it into a 1944 short story of the same title. The Man Who Lived Underground was finally published this last spring by the Library of America, with very good contextualizing essays and Wright’s stimulating and wide-ranging “Memories of My Grandmother,” in which he traces the personal influences on the book.

He doesn’t dwell on one of the most obvious ingredients, probably because it was so pervasive in 1940s media: the power of a crime plot. Native Son had centered on a homicide, rendered from the killer’s viewpoint. This novel does the same with robbery, sinking us thoroughly into Fred’s mind and registering everything that happens in personal, sensuous detail. The cops of the opening come out of hard-boiled tradition, and Fred becomes another of all those wrong men fleeing the police in film and fiction. Hitchcock might well have agreed with a point Wright makes in his memoir: “I believe that the man who has been accused of a crime he has not committed is the very person who cannot adequately defend himself.”

I don’t want to trivialize a powerful book by saying it’s “just a thriller.” For one thing, Wright shows that thriller premises can be valid vehicles for social critique. But just as important, a crime plot can draw readers to engage more deeply with the action. If the book lacked the pressure of the police pursuit, and simply showed Fred as a vagrant touring the underground life of LA, it would be more episodic and diffuse. When Fred evades the police or embarks on his raids on the subterranean city, there’s a level of suspense that is of value in its own right.

Tempted by mystery

Over the last few years, I’ve been writing a book about how popular storytelling techniques in twentieth-century media have shown their experimental side. I try to trace how nonlinear time schemes, complexities of viewpoint, and unconventional strategies of segmentation have come to create what some have called the “New Narrative Complexity.” These maneuvers, it’s claimed, now attract audiences in themselves: “Form is the new content.”

I’ll try to show that this trend, however striking it seems to us, has important precedents. Since the end of the nineteenth century Anglo-American prose fiction, theatre, and film have at all levels of taste, tried out innovative methods. Audiences mastered them and some demanded more, so the pressure of competition led storytellers to try to surpass themselves and their peers. This process, I suggest, is vividly seen in the way in which mystery plots characteristic of detective stories, suspense tales, and kindred genres were escalated, mixed, and varied across the decades.

In addition, the conventions of mystery have long been incorporated into “serious” or prestigious western literature as well. Crime and its investigation have sustained plots from from Oedipus to Dostoevsky and Dickens and Henry James. Modernists haven’t resisted either. Not only did Faulkner write bona fide detective stories, most famously Intruder in the Dust (1948), but his more canonical novels depend on laying bare, through a process of investigation, family secrets. Mystery, and the puzzles and suspense it generates, pervades storytelling both High and Low and in-between.

Wright, composing his books in the Murder Culture of the 1940s, is a good example. But so too is another novel published this year, Colson Whitehead’s Harlem Shuffle.

A rising entrepreneur

Ray Carney owns a furniture store in Harlem, selling both new and used items on the installment plan. Most of his inventory is legitimate, and he prides himself on helping struggling families afford nice things. He lives comfortably with his wife Elizabeth, who’s expecting their second child. The book traces three phases of Ray’s life in tagged blocks: 1959, 1961, 1964.

Ray is part of a social milieu richly evoked by Whitehead’s exposition of the neighborhood and its politics. Period details, shop-window displays, and dynamics in the local Black hierarchy are gracefully integrated. Elizabeth’s well-off parents live on Strivers’ Row and her father looks down on Ray as a “rug merchant.” Backstory about people and places is sometimes supplied by wide-ranging external narration, but most of the descriptions are filtered through Ray’s perception. The splendor of the Theresa Hotel, the “Waldorf of Harlem,” is summoned up in his childhood memories of the spectacle of guests and performers parading in, cheered by adoring crowds.

Ray is part of a social milieu richly evoked by Whitehead’s exposition of the neighborhood and its politics. Period details, shop-window displays, and dynamics in the local Black hierarchy are gracefully integrated. Elizabeth’s well-off parents live on Strivers’ Row and her father looks down on Ray as a “rug merchant.” Backstory about people and places is sometimes supplied by wide-ranging external narration, but most of the descriptions are filtered through Ray’s perception. The splendor of the Theresa Hotel, the “Waldorf of Harlem,” is summoned up in his childhood memories of the spectacle of guests and performers parading in, cheered by adoring crowds.

From the start, we’re introduced to this social texture through a day in Ray’s life. The second sentence of the opening is:

Ray Carney was having one of his run-around days–uptown, downtown, zipping across the city. Keeping the machine humming. First up was Radio Row. . . .

At Radio Row, Ray brings some damaged radios to electronics dealer Mr. Aronowitz. There he buys TVs that supposedly “fell off the truck.” This establishes the blurred boundaries of Ray’s business, which includes a gray-market side hustle. The very full description of Aronowitz’s shop and his relation to Ray is typical of the book’s texture.

Next Ray visits a high-school friend who’s selling her sofa and chair before moving to DC. This chapter allows Whitehead to fill in Ray’s younger days and include a scene in which he reveals a surprising capacity for violence. Then Ray drives to his shop, where we’re introduced to his salesman Rusty, and the day proceeds. It’s important to establish Ray’s routines of pickup, delivery, and selling because very soon they will be disrupted.

Ray is more than a register of his surroundings; he’s an active protagonist. He is mildly driven to rise in the world. He vows to move his family to Riverside Drive “one day, when he had the money.” But he won’t turn ruthless. He’s convinced himself that he is a decent person, helping his customers, supporting his family, aiding his feckless cousin Freddie when he can. “I may be broke, but I ain’t crooked.” When he occasionally takes some sketchy merchandise or fences a few pieces of jewelry Freddie has stolen, he calls himself merely “a middleman.”

By now the reader suspects that this is a story about a decent man’s slide into high-risk compromise. The book’s first part bears the ominous epigraph: “”Carney was only slightly bent when it came to being crooked . . .” Only slightly bent may be bent too much.

Not a spoiler, a teaser

What I haven’t told you is that each of the book’s three parts depends on a plot schema derived from the mystery tradition. Part One centers on a heist, a bold jewel robbery of the landmark Hotel Theresa (above). The second part is a story of political bribery and the revenge taken for a double cross, in the vein of Hammett’s Glass Key. Part three starts with a robbery but becomes a man-on-the run plot. These conventional action arcs give propulsion to the social and psychological dimensions of Ray’s activities.

Whitehead acknowledges the influence of the crime tale. According to a profile in the Times:

Whitehead steeped himself in novels by Chester Himes, Patricia Highsmith and Richard Stark, one of Donald Westlake’s pen names.

These three writers neatly parallel the book’s three parts: Stark for the heist, Himes for the Harlem backroom intrigue, and Highsmith for the suspense-driven finale. Whitehead’s editor notices the blend and sees the genre dimension as a vehicle for the book’s themes:

“What Colson does with the heist genre, he hits all the marks, the dialogue is fabulous, but as you get further into the story, you begin to realize the depths of what he’s up to,” said Bill Thomas, editor in chief and publisher of Doubleday. “You begin to see he’s using the tropes of the crime genre to tell a much larger and deeper story.”

It works the other way too. Without these “tropes,” readers would be less gripped by the social critique. (By the way, I’d argue that a lot of genre fiction does “tell a much larger and deeper story,” while also offering other pleasures.)

Whitehead smoothly integrates the crime elements with the tradition of the twentieth-century American social-psychological novel (Wharton, Fitzgerald, O’Hara, et al. up to Bellow and Updike). He pulls a bait-and-switch in the very opening. I reported the opening’s second sentence, but I left off the very first one.

His cousin Freddie brought him on the heist one hot night in early June. Ray Carney was having one of his run-around days–uptown, downtown zipping across the city. Keeping the machine humming.

We won’t hear of the heist again for another twenty pages, but that first sentence is enough to prime us to keep going.

We’re eased into the crime plot by another addition to Ray’s itinerary on that first day, a visit to the somewhat shady bar Nightbirds, which is revealed as part of his common routine. Soon enough Freddie is pitching his plan, and the book moves into the canonical heist pattern I’ve discussed before.

The bulk of the first part’s action takes place in the aftermath phase of the heist, a common option. Like classic caper stories, Harlem Shuffle plays with time and viewpoint, shifting to a flashback that renders Freddie’s experience during the robbery–all of which enhance the classic effects of suspense and surprise. Back in the present, the tension rises. Ray gets a visit from a rival gang, rendered in pure hardboiled prose, filtered through Ray’s panic.

He’d have to satisfy himself with making it through the meeting in one piece.

The safecracker dismissed the class.”We keep our mouths shut,” Arthur said, “see how it shakes out. Then divvy it up like we planned. ” Miami Joe never closed a job unless he was satisfied they were free and clear.

The meeting ends with Ray facing a deadline: “Four days for Carney to come up with an angle.”

I’ve gone a little too far into the action, maybe, but please consider this as parallel to the way Whitehead treats his first sentence. I’ve offered not so much a spoiler as a tease. I can’t see any other way to show how elegantly the book absorbs genre conventions while aiming at a broader analysis of Harlem life and Ray’s character.

Thick local history

Barber shop; The Undefeated.

Since I’m interested in style, I was struck by several strategies that Whitehead uses to pursue the “larger and deeper strategies” that “purer” crime fiction seldom attempts. One strategy is more elaborate description, often thickened through adding a historical dimension.

Contrast Chester Himes’ wild tale of a single night of cascading crime, A Rage in Harlem (1957), set roughly in the middle of the three eras Whitehead presents. Himes’  book is driven by spurts of dialogue and frantic pursuits, captures, escapes, fights with fists and knives and pistols. The plot is kicked off by a preposterous machine that can transform ten-dollar bills into hundreds, and it ends with a hearse tearing through night streets bearing (supposedly) a trunk full of gold. Before things go spinning out of control, however, the hapless protagonist Jackson calls on his brother Goldy, whose scam is to dress up like a nun and beg in front of the Teresa Hotel. A chapter starts:

book is driven by spurts of dialogue and frantic pursuits, captures, escapes, fights with fists and knives and pistols. The plot is kicked off by a preposterous machine that can transform ten-dollar bills into hundreds, and it ends with a hearse tearing through night streets bearing (supposedly) a trunk full of gold. Before things go spinning out of control, however, the hapless protagonist Jackson calls on his brother Goldy, whose scam is to dress up like a nun and beg in front of the Teresa Hotel. A chapter starts:

The plate-glass front of Blumstein’s Department Store, exhibiting eye-catching items of wearing apparel and house furnishings for the residents of Harlem, extended from the back of the Hotel a half block down 125th Street.

A Sister of Mercy sat on a campstool to one side of the entrance, shaking a round black collection-box at the passersby and smiling sadly.

So much for the milieu. Before Elmore Leonard explained, “I tend to leave out the parts that readers tend to skip,” Himes was practicing a minimal functional description of the wares in Blumstein’s window. Now here is Whitehead on another shop display:

Sterling Gold & Gem was a venerable jewelry store on Amsterdam, ten blocks up. The dusty orange bulbs in the sign out front blinked on and off to simulate movement, like a greyhound dashing around a track. Young lovers knew the engagement rings and wedding bands out front, while the drawers of uncut stones and hot merch in the back catered to a more disreputable clientele. Given his insulting rates, the owner, Abe Evans, was a fence and Shylock of last resort. . . .

…and so on, with several more sentences about Evans’ business conduct, eventually bringing us back to Carney’s mind with a button: “Fancy that.”

Whitehead gives us a sharp picture of the display as a visual attraction, complete with a simile, followed by an account of innocent lovers, before taking us back to the dirty part of the business. He provides a glimpse of the “deep history” of the store, while Himes is minimally concerned to anchor his new scene geographically.

The contrast isn’t simple. Whitehead needs to establish Abe on his entrance into Carney’s situation, as Himes needed to set up Goldy–which Himes soon does through backstory after the passage I quoted. To supply a more dense backstory to the window display would slow up Himes’ grim comic extravaganza as it’s building steam. And Whitehead isn’t above using a classic scenic hook, a mention of Sterling Gold & Gem, in the paragraph just before, which smoothly justifies filling in Evans’ backstory. I just want to suggest that Whitehead’s back-and-fill description, showing that patterns of social behavior pervade even consumer goods, is typical of a register of writing that tries to steep plot action in cultural implication.

If Himes asks us to tease significance out of howlingly outrageous situations, Whitehead points us toward innocuous items as a cluster of signs that need deciphering. It’s an effort to saturate every moment with implicit meanings that merge with the broader themes of the book. This story of the gnawing corruption of an ordinary man depends on the same disparity: the innocent hearts of young lovers and the man who uses them as pretexts for more or less petty crimes.

Thick description, laced with metaphor, is only one strategy for “lifting” crime schemes to the level of “serious writing.” Chandler got credit for the same thing, as does John le Carré now. Wright employs the same technique in The Man Who Lived Underground.

Style of this sort is exactly what the mainstream prestige novel has promoted for over a century, but it needn’t supply our only criteria for exciting narrative. The virtues of the Himes approach are can be found in Hammett, particularly in the Continental Op stories. Minimalism has its own power, in speed, force, and the creation of a pulsating rhythm.

There are dimensions to The Man Who Lived Underground, A Rage in Harlem, and Harlem Shuffle that experts in African American literature could detect and that I can’t. Of course those dimensions should be explored; we should strive to know artworks as intimately as possible. To that end, I’m interested in how formal and stylistic techniques available to many storytellers of different sorts can be mobilized to engage audiences–and to straddle the boundary between “high art” and “mass art.”

More specifically, my book is an effort to show the formal and stylistic achievements of a genre that in its most intriguing experiments modifies or challenges canons of Serious Literature. A robust storytelling tradition forges its own tradition of craftsmanship, and that tradition is open to borrowing from anyone. Of course we cinephiles have known about this possibility for a long time.

As several critics have pointed out, Whitehead has blended genre conventions into other work, notably The Underground Railroad, with its alternative-reality/ steampunk premise of a real railway helping runaway slaves escape. I’d just add that the novel and the streaming series based on it adhere to classic mystery schemas: an investigation pursued by an implacable tracker, and a couple on the run.

The book I mention is currently titled Perplexing Plots: Popular Storytelling and the Poetics of Murder. It’s slated to be published by Columbia University Press, with no release date yet established.

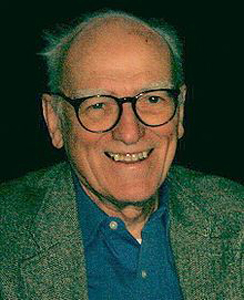

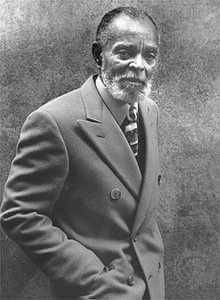

Donald Westlake; Chester Himes; Patricia Highsmith.

Little things

Equinox Flower (Ozu, 1958).

DB here:

Academic critics and fans share a passion for looking closely at the movies we admire. A lot of film critics enjoy spiraling out from the film to ponder Big Ideas, which is okay, I guess. But I confess I particularly enjoy digging in for trouvailles (great word), lucky discoveries that passed me by on earlier encounters.

Across my career, many of the directors I admire seem to have tucked in little things just for me (or you). They don’t necessarily carry meanings; they’re quietly decorative, subtly off-center to the narrative. Tati slipped peculiar items into the corners of the frame. Sturges offered gags that only people with his sense of humor will find funny. A successful crowdsourcing enterprise exposed Welles’ homages to early film. Above all, Ozu nudged me toward red teakettles and surprising details. Who else lines up the levels of beverages in a table setting, and then matches that plane to the edge of a fruit bowl?

If you care enough about my movie, the director seems to say, I’ll reward you with a trouvaille. Here are two I found recently.

Showing the stitches

Sometimes a trouvaille is a felicity of craft. The director quietly shows off his virtuosity to those in the know. While studying Pulp Fiction for a book I’m finishing, I noticed that Tarantino sets up the ending in a sidelong way.

You’ll remember that the opening shows Honey Bunny and Pumpkin discussing how a restaurant is one of the safest robbery targets. Abruptly they launch an assault on the diner. Then they drop out of the film for a couple of hours.

Very likely we’ve forgotten about them when Jules and Vincent settle down for breakfast in a diner. After discussing the virtues of pork products and the prospects for Jules’ future, Vincent rises to go to the toilet. As he pauses, it’s possible, but not easy, to discern the larcenous couple out of focus in their booth behind him. Given their peripheral status and the centrality of Travolta’s performance, I suspect that almost no one notices them on a first viewing.

Soon after Vincent has left, we’ll hear a repetition of the final bits of the couple’s conversation and we’ll see a replay of their leaping up to announce the robbery. Tarantino has rewarded the sharp-eyed viewer with a slight anticipation of the replay, and a hint at how his film will fold back on its opening sequence.

But this echo is matched by a “pre-echo” during the opening sequence. As Pumpkin and Honey Bunny plan their heist, a close view of her includes a bulky man in a t-shirt walking into the distance.

At this point, a first-time viewer hasn’t been introduced to Vincent, so the t-shirt guy is just part of the scenery. Only in retrospect do we realize that here Tarantino is anticipating, and overlapping, the portion of the robbery that we’ll see in the final moments of the film.

Here the critic/fan is invited to appreciate how carefully made the film is. It’s a quality we don’t sufficiently recognize in Tarantino: a delight in fine-grained formal niceties.

Easter Egg, avant la lettre

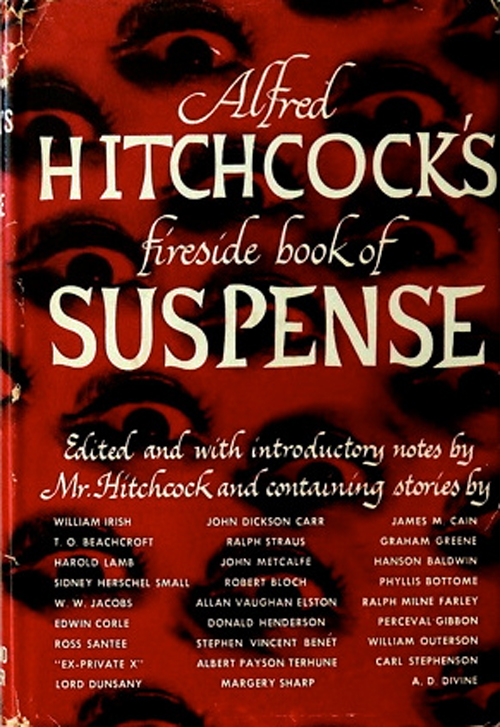

In Hitchcock’s Strangers on a Train (1950), tennis pro Guy Haines is introduced (implausibly) reading a book on his trip. Soon he’s accosted by the spoiled, marginally nuts Bruno Anthony, and the plot gets under way. Only a fan, or a critic, will want to know: What’s Guy reading?

It’s not easy to tell. We don’t get a close-up of the book. The best we can tell, from above, is that it’s a hardcover, with a photo on the back of the dust jacket. Later, after Guy and Bruno have shared a meal in a compartment, we can glimpse the spine.

Blown up, thanks to the glory of Blu-ray, the spine looks like this.

A little research reveals that the volume is Hitchcock’s collection of stories published in 1947 by Simon and Schuster.

Several anthologies were published under Hitchcock’s name from the 1940s onward, but most were in paperback. This was a more prestigious item, and I suspect it helped the branding effort that was underway during his Hollywood career. The picture on the back is of Hitchcock, of course. (My copy lacks a dust jacket, so I can’t supply that.) But the resonance comes from the fact that I was reading this very book as part of preparation for my own study of 1940s mystery culture.

It’s not exactly product placement; the book’s presence is too fleeting to register with audiences, surely. Including the book seems more in the nature of a private joke among Hitch and his team. Guy is a man of good taste, reading a book by the man directing the film he’s in.

Today we’re familiar with Easter Eggs, those bonus materials that establish a complicity between filmmmaker and viewer. Is this an early example? It could be a prize for fan connoisseurship. The book isn’t emphasized, being buried in the mise-en-scene, and so it encourages the devout to poke and probe. It also points outside the film to the production context. Still, how many 1950 viewers, lacking our ability to freeze and magnify the frame, could have spotted it? Perhaps only the devotion of a modern fan, aided by new technology, can bring this trouvaille to light. An incipient Easter Egg, then, awaiting digital technology to be discovered?

Once we’re down this rabbit hole, let’s scramble further. What stories might Guy be reading? There are two hints. We have the placement of the jacket flap in the shot above, and an earlier shot showing the book open.

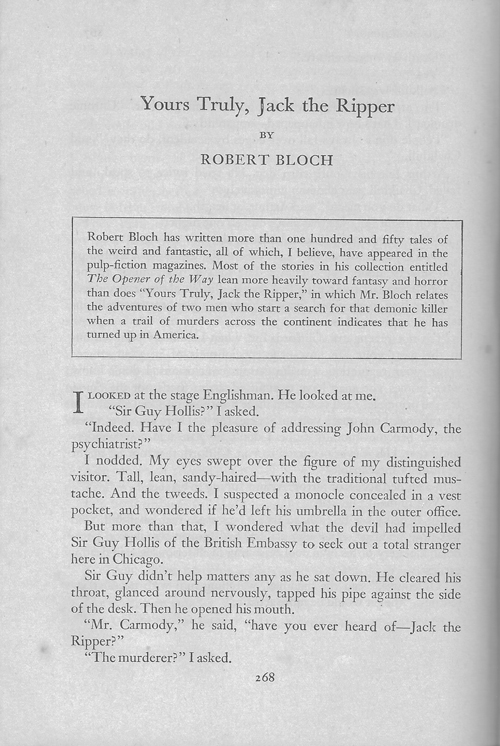

As best I can tell, the story Guy’s reading is likely to be “Yours Truly, Jack the Ripper.” It tells of a psychiatrist who meets an Englishman called “Guy Hollis.” Sir Guy believes that Jack the Ripper has migrated to the US and is at large in Chicago. With the aid of the psychiatrist, Sir Guy finds him. Apart from the name Guy, the correspondence to Strangers it would seem to involve a peculiar bond between two men, one of whom is a psychopathic killer.

But there’s another, stranger affinity.

The author of “Yours Truly, Jack the Ripper” is Robert Bloch., whose novel Psycho would furnish Sir Alfred his 1960 film. Coincidence? In the land of trouvailles, are there any coincidences?

Fans have raked over these movies assiduously, so I can’t imagine I’m the first to notice these fine touches. No matter. When you discover them on your own, you still feel a tiny thrill of communicating with the filmmaker, behind the backs of all those folks who didn’t notice. Ozu, I often feel, is making movies especially addressed to me. It’s an illusion, of course, but I refuse to give it up.

Thanks to the University of Wisconsin–Madison Filmies listserv for helping me understand what counts as Easter Eggs, and for a reality check on my sanity.

This site includes lots more on Hitchcock, Ozu, Sturges, and Tarantino. My book on Ozu is available from the University of Michigan. It takes time to download, so be patient.

P.S. 15 August 2021: As I thought, I’m not the first. A mere twenty-one years ago, Dana Polan in his monograph on Pulp Fiction (British Film Institute) noticed the pre-echo of Vincent headed toward the toilet. Good going, Dana! Film analysis wins again.

Days of Youth (Ozu, 1929).