Archive for the 'Animation' Category

Dante’s cheerful purgatorio

Twilight Zone: The Movie.

DB here:

When will we baby boomers relax our chokehold on popular culture? Never, if the enthusiastic response to Joe Dante’s visit to Madison last weekend is any indication. A showing of Gremlins (1984) packed the house. A screening of his Twilight Zone: The Movie episode brought fans forward with DVD slipcases to sign. College kids reminisced about watching The ‘burbs with their dads and Explorers with their buddies (all on video, of course).

Although steeped in classical Hollywood, intimately acquainted with the most obscure output of the studios, Dante hasn’t abandoned the present. He shoots TV shows, webisodes, and the 3D feature The Hole (still awaiting a US release). He hosts a website, Trailers from Hell, in which directors comment on other directors’ works using a trailer as a point of departure.

His films, from Piranha (1978) and The Howling (1981) to the present, by way of Amazon Women on the Moon (1987) and Matinee (1993), combine the gonzo spirit of the 1960s with a good-natured reverence for the past. Particularly movies. Particularly crazed, tasteless movies. Like Spielberg and Peter Jackson, he’s a fanboy. “Most filmmakers are kids at heart,” he says. “And all actors are.”

Unlike Spielberg and Jackson, though, Dante keeps politics close to the surface. His films sustain the baby-boomer hope that you can squeeze cultural critique into a genre project. Everybody knows that the Gremlins movies are subversive trips into the shadows of bourgeois normalcy. Has a shiny kitchen blender ever been used more efficiently?

The Gremlins pictures and The ‘burbs are valentines compared to Homecoming, Dante’s installment in the series Masters of Horror. This asks a simple question: Suppose that all the soldiers killed in combat were able to come back and vote? Is that a powerful lobbying group or what? When resurrected vets of Iraq start stalking to the polls, an Ann Coulter lookalike tries to stop them. Run on cable in 2005, this left-wing zombie movie slashes to ribbons pious platitudes about war’s costs. It’s required viewing for all 2012 presidential candidates.

Don’t crowd me, Joe

Dante began his career as a collagist. That’s not too fancy a name for a man who, with his friend Jon Davison, collected the ephemera of the great age of 16mm. TV shows, ads, and movie trailers swept out of local stations went into their archives. In time these and other glories of late-night TV found a new life, like a monster stitched together out of morgue remains. The strategy was simple. Dante and Davison rented five or six 16mm sub-B features and projected stretches of them, in rough order but jumbled together. The movies were interspersed with reels of clips.

The Movie Orgy played college campuses in the late 1960s and early 1970s. The Orgy lasted about seven hours, and its auteurs urged viewers to drift in and out. “Go get a pizza whenever you want. You won’t miss a thing.” Eventually Schlitz hired them to take it around the country and sold beer at the screenings.

When Dante began working for Roger Corman’s company—cutting trailers, thereby tapping his skills as a collage-maker—The Orgy was suspended. But some years ago the footage that he could find was transferred to digital and played at the New Beverly. It found a new success. Dennis Cozzallo has a lively tribute from 2008 here. Needless to say, we had to have The Orgy for Dante’s visit to Madison.

Affection for the detritus of the media takes many forms. After watching too many campus simpletons (both students and profs) laugh mockingly at Fritz Lang and John Woo movies, I’m opposed to condescension. I suspect Camp in its disdainful form. I don’t like people demonstrating their sense of superiority to the trash their parents and grandparents enjoyed. Knowingness leaves you with nothing.

But The Movie Orgy is different. It offers another take on subpar product: The pleasure of sheer unpredictability. How will common sense be violated? How will demands of craftsmanship be dodged or bungled? How will canons of taste be overturned? How will things that were once stupid, and remain stupid, and will be stupid forever, still communicate a certain cynical earnestness? A foolish idea carried off with obstinate conviction will always deserve respect, so Earth vs. The Flying Saucers and Beginning of the End wind up having a touching desperation, like the badly-tied noose in a suicide hanging.

But The Movie Orgy is different. It offers another take on subpar product: The pleasure of sheer unpredictability. How will common sense be violated? How will demands of craftsmanship be dodged or bungled? How will canons of taste be overturned? How will things that were once stupid, and remain stupid, and will be stupid forever, still communicate a certain cynical earnestness? A foolish idea carried off with obstinate conviction will always deserve respect, so Earth vs. The Flying Saucers and Beginning of the End wind up having a touching desperation, like the badly-tied noose in a suicide hanging.

Moreover, in sequence after sequence, there’s a quality of astonishment that doesn’t make us feel superior. Take one exemplary moment of dépaysment. If you and I tried to be naive or trashy, we couldn’t come up with this.

Andy Devine hosted a kiddie TV show, Andy’s Gang, which featured Froggy the Gremlin (Plunk your magic twanger, Froggie!), the cat Midnight, and Squeeky the mouse (played by a hamster). About an hour into The Orgy, Andy induces Midnight to play a miniature pipe organ while Squeeky accompanies him. Cut to a deep-focus shot of what seems to be a slightly drugged cat locked in place and rhythmically pawing the offscreen keyboard. In the background Squeeky, apparently clamped within a mechanical mouse body, bangs a tiny bass drum. Andy sings along tunelessly. The song is “Jesus Loves Me.”

You don’t laugh, you gape. It’s like one of our local attractions, The House on the Rock: What’s disturbing is not that it’s done poorly, but that somebody thought of doing it at all.

The form of The Orgy—and it does have a form, of sorts—is to open with openings and end with endings. Several of the movies get started in the first half hour (Dante and Davison love opening credits) and we’re given enough of the plots to become curious. Most prominent are Attack of the 50-Foot Woman and Speed Crazy, the latter receiving a loving dissection highlighting, and repeating to the point of obsession the heel protagonist’s tagline, “Don’t crowd me, Joe.” Eventually the guy and his flashy sports car wind up crowded, all right–crowded into a ravine.

More TV episodes and movies get added as the hours roll by, and by the end we’re facing Armageddon. Los Angeles, Las Vegas, Chicago, New York, DC—every major city is under attack by some alien or giant monster. Sky King has to dump dynamite for some reason, Superman has to save Lois from a pistolero. A sort of amphetamine Intolerance, The Movie Orgy cuts together all these climaxes, which include The End titles that are far, far from signaling the end.

The clip from Andy’s Gang reminds us that the piece is somewhat misnamed. It’s a Movies And TV Orgy. More specifically, it’s a Movies On TV orgy. The structure of the whole shebang imitates a long stretch of television ca. 1955-1960. Over lunch Dante recalled watching Million Dollar Movie as a kid in New Jersey, seeing a feature shoehorned into a ninety-minute slot and chopped up by commercials. The Orgy replicates the jagged tempo of switching among three or four channels, glimpsing variant commercials for Colgate toothpaste or Raleigh cigarettes, catching a bit of this movie and then a bit of that one. With all its kid shows from my youth (The Lone Ranger, Lassie, Mighty Mouse, etc.) in endless eruption and interruption, it’s a baby-boomer time capsule. Puncturing this evocation of childhood are the clips scavenged from teenpix and Dick Clark’s dance show, Vietnam, Nixon’s Checkers speech, and film-society icons like the Marx Brothers, Fields, and Abbott and Costello. The late sixties counterculture breathes more fully in some clever fake ad spots. In one, a crucifix starts to wobble as the carved Jesus struggles to free his hands.

Dante claims that he and Davison were inspired to find out about the popular culture that shaped their parents’ generation. But nearly everything we see filled the airwaves during our younger days as well. The Movie Orgy in its current form seems to me a zestful celebration of the world our generation saw when we flopped on our bellies, propped our chins in our hands, and stared at the tumultuous world inside a black-and-white (not color) TV (not video) set (not monitor).

We cartoon characters can have a wonderful life

Dante the collagist leaves his fingerprints all over another film he screened here. When Spielberg launched his Amblin company, he hunted for directors who could make family entertainment in a genre format. Dante, who had already started Gremlins, was invited onto the omnibus Twilight Zone project. After the fatal accident on the Landis set, the studio backed off and it become “a movie they wanted to make but didn’t want anything to do with.” This gave Dante wide latitude and made him think, mistakenly, that studio suits always leave directors alone.

For this episode, Dante wanted to do an original story but Warners insisted that it had to be based on an episode of the TV series. He went back to the original Jerome Bixby story, which Dante and Richard Matheson reworked to add cartoons as a running gloss to the comic horror. The pseudo-family of demonic little Anthony inhabits a house that is half cartoonland, half-PoMo-Caligari. Saturated colors, occasionally striped with noir shadows, provide another Dante caricature of family domesticity, but now cartoons comment on the action. When Helen steels herself to eat, the dog on the screen behind her is doing the same.

The crisscrossed shadows of the corridors are replayed in the sawtooth walls pursuing Bimbo.

The collage principle gets developed further in Dante’s use of the soundtrack. The Movie Orgy uses no new sound work; the clips are just spliced together. But for the Twilight Zone episode, let loose in Warners’ classic archive, Dante could weave in Carl Stalling music (reorchestrated for stereo by Jerry Goldsmith) and a rich mélange of daffy sound effects.

The TV is incessantly on. The cartoons running in the background supply whizzes, boinks, and thuds that jarringly punctuate the conversation between puzzled teacher Helen Foley and the family that Anthony holds in his magical grip. “This is Helen,” says Anthony, introducing her to Uncle Walt and his sister, as we hear a smash from the TV set. The cartoon tracks comment on the action too. As the family settle down in front of the tube, the elders dote on Helen and we hear a Stalling rendition of “Ain’t She Sweet?” Dinner is served to the tune of “The Teddy Bears’ Picnic.” And when Helen discovers her burger has been slathered with peanut butter, the visceral image is underscored by warbling winds that rise when she lifts the bun. Eisenstein, for reasons given here, would have loved the moment. The whole sequence plays out as live-action animation, with naturalistic dialogue and effects given a creepy overlay by the cartoon track. Is Helen Foley’s last name part of the gag?

Dante, impresario of the comic grotesque, finds his inspiration in popular culture, the more wacko and inept the better. The comedy may come from childhood silliness, the grotesque from childhood fears. They say we baby boomers will always be just big kids, and Dante accepts this with a grin and a darkly cheerful eye.

Many thanks to the resourceful Jim Healy for arranging his friend Joe Dante’s trip to Madison. Thanks as well to the Cinematheque, the Marquee, and the Chazen Museum of Art for hosting the screenings.

John Carradine in The Movie Orgy.

Scriptography

Hollywood screenwriters at work, according to Boy Meets Girl (1938).

It’s not every conference that opens a morning session by asking the men in the audience to take off their underwear.

But I anticipate.

Last weekend I was a guest of the Screenwriting Resource Network’s fourth annual Screenwriting Research Conference in Brussels. I think that a hell of a time was had by all, and I learned quite a bit, including some reasons why people are interested in screenplays.

Schmucks with Underwoods

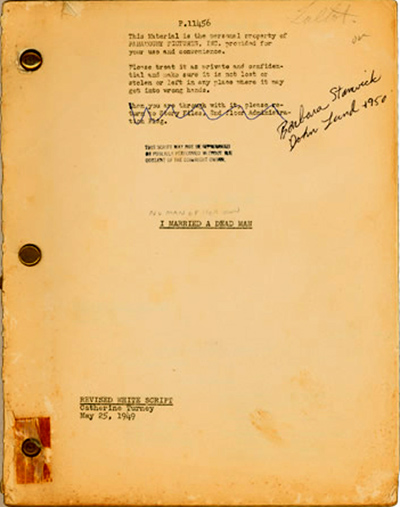

Catherine Turney script for No Man of Her Own (1950).

In my youth, there seemed to be a solemn pact among my peers that we would never study certain areas: censorship, audiences, adaptation (novels into film, particularly), and screenwriting. An earlier generation had, through patient labor, shown decisively that these subjects were dead boring. We, on the other hand, were fired by notions of the director as auteur, and indifferent to what were called “literary” and “sociological” approaches to film. So we triumphantly turned toward The Text—that is, the finished movie.

Things have changed since then. Yet there are still tempting reasons to consider the study of screenwriting a nonstarter if you’re interested in cinema as an art. If you think of the finished film as the achieved artwork, then study of screenplay drafts risks seeming irrelevant. Whatever the screenwriter(s) intended seems irrelevant to the result. So what if six or more screenwriters labored over Tootsie? The movie stands or falls by what we see onscreen.

This was the view presented in Jean-Claude Carrière’s three talks to our group. He suggested that the screenplay is destined to become landfill, and rightly so. It’s like the caterpillar that becomes a butterfly. Once the film has been made, the script has no intrinsic value.

Someone might say, “Wait! We study a painter’s sketches, a novelist’s drafts, or a composer’s early scores. These materials can contribute to understanding the finished work, and sometimes they have an artistic value of their own.” The problem is that in these arts, the preparatory materials are in the same medium as the result. But a script can’t count as a version of the film because prose can’t adequately specify the audiovisual texture of a movie. It’s commonly thought, plausibly, that giving the same script to two directors would result in significantly different films. So the script is at best a series of suggestions for filming, not a sketchy version of the movie. Why not discard it when the film is done?

The study of screenwriting has probably also lain in the shadows because of the proliferation of screenwriting gurus and how-to manuals. Every American over the age of eighteen seems to be writing a screenplay; the Cable Guy who visited me last week was working on two. So all the seminars and advice books have arguably put thinking about screenplays rather close to the amateur-script racket.

Moreover, screenplay studies seem to be part of a broader, paradoxical development in academic film studies. Today scholars have more access to films than ever before, thanks to video, festivals, archives, and the internet. Yet many researchers prefer to talk about everything but the film. More and more scholars want to study just those subjects that my cohort considered dull or irrelevant: censorship and regulation, audiences (composition, demographics, critical reception, fandom), and preproduction factors (storyboards, scripts). In addition, many academics have turned to bigger thematic ideas like film and architecture, film and the city, film and modernity. These trends of research usually make only glancing reference to actual movies, mostly mining them for quick illustrative examples.

In sum, many academics have abandoned the study of film as an artistic medium that finds its embodiment in important works. To get to know particular films more intimately, you increasingly have to go to the Net, to writers like Jim Emerson, Adrian Martin, and other sensitive analytical critics. Talking about screenwriting can seem to be another way of avoiding coming to grips with the intrinsic power of movies.

You can probably tell that one side of me shares some of the biases I’ve listed. But when I remind myself that what people should study aren’t topics but questions, I cheer up quite a bit. For there are, I think, worthwhile questions to be asked about all these areas, screenwriting included. The Brussels event gave some good instances of resourceful, occasionally exciting research into them.

Based on my short acquaintance, most of the research questions seem trained on one of two broad areas: Screenwriting and The Screenplay.

In the trenches

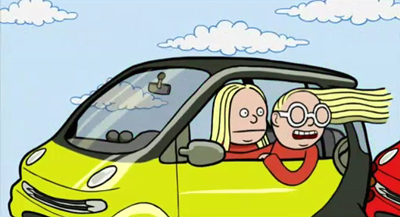

Kinky & Cosy

Screenwriting can be thought of as a practice, a creative activity with both personal and social aspects. How, we might ask, do screenwriters or directors express themselves in the script? How does a media industry recruit, sustain, and reward screenwriters? What are the conventions and constraints at work in a particular screenwriting community?

Questions like this are somewhat familiar to me. When I wrote my first book, on Carl Dreyer, I had to examine his scripts (notably the unproduced Jesus of Nazareth), and that helped me understand his characteristic methods of researching and planning his films. Later, when I collaborated with Kristin and Janet Staiger on The Classical Hollywood Cinema, I recognized a more institutional side of things. We can see from the films of the 1910s that filmmakers were cutting up the space in fresh ways. But this wasn’t a matter of directors simply winging it on the set. Kristin used published manuals and Janet used original screenplays to show that shot breakdowns were planned to a considerable degree before shooting. This habit made production more efficient and controllable.

At the Brussels get-together, Steven Price offered further evidence of this sort, which displayed some of his research on early scenarios for Mack Sennett movies like Crooked to the End (1915). Interestingly, Steven found that sometimes the later version of a continuity script was more laconic than the initial one. Perhaps the gags, once spelled out in the first draft, could be left up to the actors. This is the sort of thing he identified as a “trace” of production practices.

A parallel of sorts emerged in Maria Belodubrovskaya’s paper on screenwriting under Stalin. The Soviets, admiring Hollywood efficiency, tried to come up with a similar system. But their efforts to produce films in bulk were blocked by a censorship apparatus bent on ideological correctness. No surprise there, I guess. But Masha showed convincingly that the very efforts to mimic Hollywood’s “assembly-line” system also discouraged authors from submitting scripts. The writers thought (like many of their LA counterparts) that such a setup denied them creative freedom. In addition, the prospect of story departments providing a stream of screenplays ran afoul of the tradition that gave the director control of the final draft. And the role of producer, as one who could steer the whole process, didn’t exist! So much for the Soviet Hollywood.

What about other media? Sara Zanatta traced out the process of creating Italian TV series. She reviewed some major formats (miniseries, original series, adaptations of foreign series) and then took us through the process of creating individual episodes. Interestingly, it seems that the Italian system, unlike US television, makes the director the boss of it all. Frédéric Zeimat explained how he gained entry to the local screenwriting community through his university education, including work in Luc Dardennes’ workshop at the Free University of Brussels. Eventually he came up with a script that won prizes. He is about to become a showrunner for a sitcom.

One of the most stimulating panels I heard considered the writing of graphic novels and animation. Richard Neupert explored how recent French animation sustained the tradition of individual authorship while still acceding to some international norms of moviemaking. The cartoonist Nix discussed how he faced new problems in transferring his three-panel comic strip Kinky & Cosy from print to television. TV demanded less written text, especially signs, so that the clips could be exported outside Belgium. More deeply, Nix had to rethink how to pace the action and leave a beat (say, two seconds) after the punchline.

Pascal Lefèvre, one of Europe’s leading experts on comic art, provided a brisk, packed account of the history and practices of scriptwriting for Eurocomics. He described patterns of collaboration, format, and creative choice, placing special emphasis on comics as a spatial art different from cinema. His example was a page from Regis Franc’s ulta-widescreen album Le Café de la plage. Here’s a portion in which two periods of Monroe Stress’s life coexist in a single space. He muses as an adult while his childish self gobbles up food under the guidance of Mom.

Comics space can also change abruptly, as when a window appears in second panel.

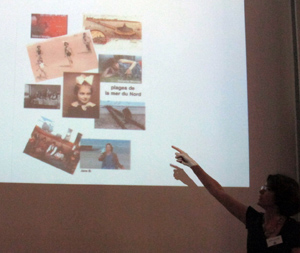

Other papers presented less institutionally fixed, more personal versions of screenwriting as a practice. Kelley Conway’s lecture on Agnes Varda exploited unique access to the filmmaker’s notebooks, scrapbooks, and databases. Kelley showed how Varda conceived three of her documentaries by means of strict categorical structures that were then frayed by digressions born out of the material she shot.

Anna Sofia Rossholm provided something similar for Bergman. Out of the vast Bergman archive she quarried sixty “workbooks,” typically one for each film. Whereas Varda’s books were filled with cutouts and images, Bergman was a word man, treating the books as diaries that recorded “this secret I.” Anna Sofia proposed that in his jottings and planning, Bergman not only communed with himself (calling himself an idiot on occasion) but also explored patterns of doubling akin to those we find in the films. The workbooks evidently held a special place for him: he included their pages in films like Hour of the Wolf and Saraband.

David Lean might be thought of as working in between the Hollywood system and the more personal European milieu. Ian Macdonald suggested that one of Lean’s unfilmed projects sheds light on what he calls screenplay poetics. Macdonald seeks, I think, a principled method for studying the creative process. He does this by tracing how a screen idea is transformed in a series of documents generated by the creative team. The process, he points out, is governed by the participants’ various conceptual frameworks. For Nostromo, Lean solicited two screenwriters and oversaw their rather different versions of the novel. Ian showed that Lean seems to have found solutions to adapting the book by fitting it to the three-act structure advocated by Hollywood artisans, a concrete case of a filmmaker accepting a fresh “poetics” or set of creative constraints.

All of these inquiries could lead to more general thoughts about the creative process in cinema. For some filmmakers, it’s a professional task, undertaken with full knowledge that problems and constraints will have to be dealt with. For others, such as Bergman and Varda, it’s obviously deeply personal, even autobiographical. Perhaps most intimate was the film discussed by Hester Joyce. New Zealand filmmaker Gaylene Preston based Home by Christmas (2010; above) partly on audiotape interviews with her father as he recalled his World War II experiences. Her script reconstructed her interviews with actors, then filled in scenes with documentary footage and scenes she imagined. It’s a family memoir on several levels: Preston’s daughter portrays her own grandmother.

The Screenplay: What is it?

Several of these probes into the creative process raise a more theoretical question. How should we best conceive of the screenplay? As a blueprint? A recipe? An outline? These labels all suggest something disposable preliminary to the real thing, the movie. But why can’t we think of the screenplay as a freestanding object? After all, there are films without screenplays, but there are also screenplays—some written by distinguished authors—that were never made into films. And some of these, like Pinter’s Proust screenplay, are read for their own sake.

In cases like this, should we consider the screenplay a literary genre? And if the screenplay for an unproduced film can be considered a discrete object, what stops us from treating a filmed script in exactly the same way? Moreover, why even speak of a single screenplay, when we know that most commercial films at least go through several drafts? Can’t we consider each one an independent literary text? We’re now far from Carrière’s idea that the script finds its consummation in the finished film and as a piece of writing it should wind up in the ashcan.

And not all screenplays are literary texts. The scrapbooks and databases that Varda accumulates are works of visual art, collages or mixed-media assemblages. Are these merely drafts of the film, or do they have an independent existence or value? We seem to be asking the sort of question that Ted Nannicelli poses in his Ph. D. dissertation. Is there an ontology of the screenplay?

Take a concrete example. Ann Igelstrom’s paper, “Narration in the Screenplay Text,” asked how literary techniques are deployed in the screenplay. When a passage in the script for Before Sunset begins, “We see…,” who exactly is this we? Ann argued that traditional narrative concepts involving the source of the narration, the implied author and implied reader, and the rhetoric of telling can illuminate conventions of screenwriting. Here the screenplay seems definitely a literary text.

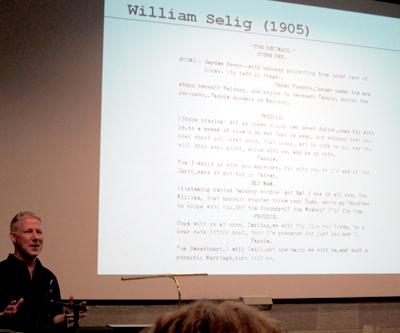

In his keynote address, “The Screenplay: An Accelerated Critical History,” Steven Price (above) declared a more abstract interest in the ontology of the screenplay but proposed that there was no clear-cut way of defining it. Historically, the screenplay takes many forms. Steven pointed out that even in Hollywood, there were many alternative formats, ranging from detailed breakdowns to the “master-scene” method (the option that didn’t specify shots or camera positions). And conceptually, the screenplay carried traces of its original production purposes, as well as other constellations of meaning. (Mack Sennett scripts seem to him part of a Sadean tradition of dehumanized, repetitive recombination.) So if there is a distinctive mode of being of the screenplay, outside of its role in production, it will turn out to be a messy one.

Envoi

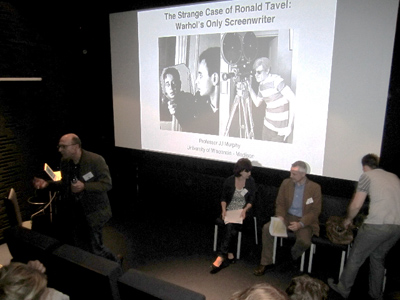

J. J. Murphy presents a paper on Ronald Tavel. Photo courtesy Richard Neupert.

If we conceive studies of screenplay and screenwriting as revolving around specific research questions, those of us interested in film as art can learn a lot. If our interests are in film history, researchers can show how organizations of production and individual choices by screenwriters/directors can shape the final product. For those of us interested in more theoretical explorations, asking about the nature and “mode of being” of the screenplay can’t help but make us think more about the ontology of cinema itself.

And if we want to know films more intimately, being aware of the creative choices that were made by the filmmakers throws a spotlight on aspects of the film we might otherwise not notice. It’s all very well to say we’ll examine the film “in itself,” but our attention is invariably selective. Knowledge of behind-the-scenes decisions can sharpen our awareness of artistic matters. Anna Sofia’s research on Bergman, like Marja-Riitta Koivumäki’s paper on Tarkovsky’s screenplay for My Name Is Ivan, activates parts of the film for special notice.

Because there were split sessions at the conference, and because I was plagued by jet lag, I couldn’t attend every panel and talk. I regret missing papers I later heard were very fine, and I haven’t written up everything I heard. I haven’t sufficiently talked about screenwriting pedagogy, represented in papers like Lucien Georgescu’s dramatic appeal to rethink whether screenwriting should be taught in film schools, or Debbie Danielpour’s stimulating survey of her methods of teaching genre scripting. So this is just a small sample of what these folks are up to. But you can tell, I think, that they’re posing questions at a level of sophistication that my 1960s cohort couldn’t have envisioned. Despite what the cynics say, there is progress in academic work.

As for men’s underpants: All is explained here.

I’m grateful to conference organizers Ronald Geerts and Hugo Vercauteren for inviting me to speak at the gathering. I must also thank conference organizer and old friend Muriel Andrin, along with Dominique Nasta and their colleagues and students from the Arts du Spectacle Department at the Université Libre de Bruxelles. My friends at the Cinematek, Stef and Bart and Hilde, helped me with my PowerPoint. Thanks as well to the Universitaire Associatie Brussel (Vrije Universiteit Brussel / Rits-Erasmushogeschool Brussel) and Associatie KULeuven (MAD-Faculty / Sint Lukas Brussel). A high point of the event was the visit to La Fleur en Papier Doré. Special thanks to Gabrielle Claes for her heartfelt introduction to my talk, not to mention a delicious bucket of moules.

A founding document in the contemporary study of the screenplay is Claudia Sternberg’s Written for the Screen: The American Motion-Picture Screenplay as Text (Stauffenburg, 1997). Other books central to the conference cohort include Steven Maras’s Screenwriting: History, Theory, and Practice, Steven Price’s The Screenplay: Authorship, Theory and Criticism, J. J. Murphy’s Me and You and Memento and Fargo: How Independent Screenplays Work, and Jill Nelmes’s anthology Analysing the Screenplay, which includes many essays by members of the group. See also the affiliated Journal of Screenwriting.

For more information on the Screenwriting Research Network, go here. (Thanks to Ian Macdonald for the link.) The next conference will be held in Sydney, and the 2013 one will take place in Madison, Wisconsin.

P.S. 22 Sept 2011: A panel discussion with Jean-Claude Carrière held during the conference is available here. Although the site is in Dutch, the discussion is in English. Thanks to Ronald Geerts for the information.

P.P.S. Thanks to Joonas Linkola for a spelling correction!

Coke does go through you pretty fast. Richard Neupert at a Coca-Cola machine that exploits a Brussels landmark.

An all-too-short visit to Ebertfest 13

Tulip’s unique way of expressing delight at the prospect of walkies.

Kristin here–

With David still recovering from pneumonia, I drove down to Champaign-Urbana by myself for a truncated Ebertfest visit. As always,  the event began with a reception at the president’s home, where Roger delivered a speech via his talking computer (left).

the event began with a reception at the president’s home, where Roger delivered a speech via his talking computer (left).

This year, rather than kicking off the festival with a Wednesday-night screening of a 70mm print, the opening program was a screening of the restored version of Metropolis, incorporating footage found in Argentina. (David has already blogged about the new version, having seen it last year at the Hong Kong Film Festival.) I had the privilege of introducing the screening.

Roger’s program notes gave a good summary of the film and its latest restoration, so I talked a little about why it’s not all the odd that a nearly complete print should be found in Argentina. First there’s the matter of what happened to prints at the end of their theatrical circulation in the silent era. Films didn’t open around the world day and date the way they do now. Prints might be exhibited in one country, then move onto another with new intertitles in a different language cut in. They might be shown for years, until their useful life was over. By that point they might have reached places far away from their place of origin. They were also usually covered with scratches and lines, and they weren’t worth the cost of shipping them back to their makers. They might be buried, as was the case with the 1978 Dawson City find in Alaska, or stored in the attic of a theater, or rescued by a projectionist who tucked them away in a garage. In some cases, collectors acquired them, as happened with the Argentinian Metropolis print. Occasionally these treasures come to light, as recently happened when the Film Archive of New Zealand located several American titles, such as John Ford’s lost silent film Upstream. So far-flung places that long ago were the end of the line for prints are where we might expect them to resurface. Indeed, New Zealand’s archive also held a print of Metropolis that contained some shots not found in earlier restorations or in the Argentinian print, and these appear in this latest version.

A second reason why Argentina is not a surprising place to find a long print of Metropolis has to do with the German film industry’s strength after World War I. Despite having been defeated, the country built up its production until it was second only to Hollywood. European companies found it difficult to sell their films in the U.S.; then, as now, American films dominated their domestic market. German companies sought other areas where they could compete on a more equal footing. They were quite successful in South America, and Fritz Lang’s films were among the most popular there. Small wonder, than, that a well-worn, largely complete print should survive there.

The original score has been reconstructed, but as has become customary at Ebertfest, the Alloy Orchestra supplied their own original accompaniment. (See below.)

Dog-lovers’ delight

The thing that sets Ebertfest apart from other festivals is that it reflects the taste of one person. Roger chooses the films, and his reviews are reprinted in the program as notes. When Roger saw the acclaimed animated film My Dog Tulip, based on J. R. Ackerley’s memoir about life with his Alsatian, he was reminded of another man whose only love was his dog, Umberto D. So, having the ability to program of double feature of the two films, Roger did. Apart from the annual silent film, Ebertfest seldom shows older classics, so this was something of a departure. I had only seen a 16mm copy of Umberto D, way back in my graduate-school days, so it was great to see a 35mm print on the big Virginia Theater screen.

The juxtaposition of the two films worked well, with the grim image of old age and despair of Umberto D followed by the nostalgic but fairly upbeat My Dog Tulip. Judging by the questions and comments afterward, the latter struck a particular chord with dog lovers in the audience, and during the remainder of my stay I heard many pet anecdotes exchanged among people around me.

The film was created by a husband-wife team, with Paul Fierlinger drawing on a digital tablet and Sandra Fierlinger painting in the colors with a computer program. As I pointed out during the panel discussion after Nina Paley’s Sita Sings the Blues was shown at Ebertfest in 2009, computer animation doesn’t mean that the computer does all the work. Far from it. A computer has to have a lot of material fed into it before it can aid in the filmmaking process. Each frame of My Dog Tulip was done by hand, and it has the look of traditional cel animation. (As with traditional cel animation, the Fierlingers use each image twice in a row, so that only twelve drawings suffice for a second of film.) There’s a deliberately rough, slightly jittery look to the outlines of the figures in the shots, helping give that impression of drawn animation.

Ordinarily I would have preferred to see the film in 35mm, but Paul and Sandra told me that the 35mm prints actually washed out some of the vibrancy of the intended colors. The digital print projected at Ebertfest definitely did the colors justice.

Matt Soller Zeitz with Paul and Sandra Fierlinger onstage after the screening

Filling the big screen

On Friday, two very well-known directors presented beautiful, color, widescreen 35mm prints that looked terrific–and huge–on the big screen. (I was sitting in the second row for one, the first row for the other, so the effect was particularly overwhelming.) I had missed Richard Linklater’s most recent release, Me and Orson Welles, in first run, so it was a pleasure to catch up with it. As all the reviewers remarked, Christian McKay uncannily impersonates the real Orson Welles. As Linklater pointed out, McKay was in his  mid-30s at the time of filming, while Welles was a mere 22 during the time depicted–and yet the portrayal works, since Welles didn’t really look young, even at the beginning of his career.

mid-30s at the time of filming, while Welles was a mere 22 during the time depicted–and yet the portrayal works, since Welles didn’t really look young, even at the beginning of his career.

The film pulls a great deal of humor out of rehearsals for Welles’s famous 1937 staging of Julius Caesar, with the director’s whims and ego dominating the proceedings, and Zac Efron’s stagestruck high-school kid providing a naive point of view of the backstage politicking. Given all the antics in the lead-up to the premiere, it’s impressive that Linklater manages to switch gears abruptly and present snippets from the production itself that genuinely suggest the impact of Welles’s revolutionary staging. It wowed New York and pioneered the way for modern-dress versions of the Bard’s works.

The on-stage discussion after the film revealed that the production, which manages to convey 1930s New York so convincingly, was mostly shot on the Isle of Man. The British island not only offered favorable production incentives, but it boasted a well-preserved local playhouse that could double for the long-since-destroyed Mercury Theater.

That evening veteran director Norman Jewison presented one of his less well-known films, Only You (1994). It’s a screwball, absurdly romantic comedy starring Marisa Tomei and Robert Downey Jr., both looking very young and very gorgeous.

After Jewison moved from television into feature films in the 1960s, his early projects included two Doris Day and Rock Hudson comedies (The Thrill of It All and Send Me No Flowers), and he returned to the genre with Moonstruck.

Only You has a slender plot in which the heroine, convinced that a Ouija board has given her the name of the man she will marry, abandons her fiancé to follow a man she thinks is her destined true love across Italy. Cinematography by Sven Nykvist and location shooting in Venice, Rome, and Positano give the film considerable charm.

David has been recovering well, but I didn’t want to leave him alone too long. I returned home today rather than staying through the entire festival. But it was a wonderful few days, and I enjoyed talking with Michael Barker, Paul and Sandra Fierlinger, Kevin Lee, Michael Phillips, David Poland (when he wasn’t busy chasing his lively 15-month-old son), some of Roger’s “Far-flung Correspondents,” and many of the devoted audience members who return year after year to this unique event. With luck, both David and I will be there for the whole event next year.

(From the Ebertfest website)

Note: For a second year, the introductions, post-film discussions, and morning panels were streamed live, and they’re also archived online.

Three minutes of “Three Brothers”

Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows Part 1

Kristin here:

Last wee I went to see Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows Part 1. Behind the pack, of course, since it had been out nearly a month. But I dislike watching films in a crowd. My ideal is to be alone in the theater, which David and I managed last week with Megamind. In this case I picked the first matinee on a school day and saw the film at our local Sundance multiplex. (Yes, even Sundance runs some popular films to help support the less successful art films.) I figured that noisy youngsters, even if they skipped school to see DH1, wouldn’t go to Sundance. I was right. Four or five adults were sitting about ten rows behind me. I never heard a peep or crackling candy wrapper out of them. The film was really film, too, 35mm.

I had been curious about how the filmmakers would deal with some of the stranger aspects of J. K. Rowling’s seventh and final book. Breaking it into two parts seemed an obvious and smart move, and it does have less of a rushed feeling than the previous adaptations had. But Deathly Hallows the book has some very unconventional aspects.

For a start, Rowling reveals dark, indeed downright nasty things alleged about Albus Dumbledore, who up to this point has been your standard-issue comic-but-wise, twinkly-eyed mentor figure. I wondered if the film would dare to do the same. It does, but so far only as a very minor side issue. In the first part, at least, Harry is obviously distinctly miffed that Dumbledore hasn’t left him more information about how to deal with horcruxes, but he doesn’t seem to feel that his hero had feet of clay.

Second, it seems downright perverse on Rowling’s part that in a long series which has come to focus on the search for horcruxes and should just be working up its climax, she throws another set of mysterious, lost objects, the three Deathly Hallows, at us. Let’s see, six horcruxes, three hallows. What’s the difference? Which should the characters be seeking, and why? Is Voldemort after them, too? In the book, Harry becomes obsessed with finding the hallows, even though the horcruxes are the main point. That last premise, Harry’s obsession, hasn’t shown up in the film, so far anyway, but otherwise the hallows are fully treated in the film.

Finally, Rowling gives us a very long portion of the book where Harry, Hermione, and, for a time, Ron, are fugitives moving from place to place, camping out each night as they try to figure out where the remaining horcruxes are—and not having much luck either with that or with destroying the one they have obtained. I personally think this is a rather daring move. Given that for this long section we are confined entirely to Harry’s point of view, we get little sense of what is happening in the outer world. Naturally the film can’t spend quite as much of its length on this period of nomadic existence. Still, it does devote an unexpectedly long time to portraying it.

Some critics have complained that the action stalls during this portion. Others have noted that the slow-down allows for us at last to linger over the psychological states of the three main characters, who are being worn down by fear, frustration, and the horcrux’s presence. This stretch also displays some beautifully bleak locations, well filmed. Plus, as Rowling no doubt intended, this part of the narrative conveys a real sense of the characters’ seemingly hopeless position: They are in great danger and without any apparent clue as to where to look next.

One minor obstacle that I remember noting when I first read the book is that the hallows are introduced by having Hermione read aloud a fairy tale from the book Dumbledore has bequeathed to her, The Tales of Beedle the Bard. The tale, “The Tale of the Three Brothers,” occupies only about two pages, but having someone read that much text aloud in a film can be deadly.

The filmmakers came up with a solution that is both inspired and extremely well executed. As Hermione reads, we see a roughly three-minute animated sequence that illustrates her words.  The filmmakers have acknowledged that their model was Lotte Reiniger’s technique of silhouette animation, which she developed in the 1920s and used for such classics as The Adventures of Prince Achmed (1926). For DH1, similar silhouette effects are achieved with 3D digital animation.

The filmmakers have acknowledged that their model was Lotte Reiniger’s technique of silhouette animation, which she developed in the 1920s and used for such classics as The Adventures of Prince Achmed (1926). For DH1, similar silhouette effects are achieved with 3D digital animation.

I wondered who had designed and animated this little sequence and determined to watch for references to it in the credits. As is typical with effects-heavy films these days, several companies were listed and the credits rolled by too quickly for me to catch much. Still, I don’t think that the little film-within-a-film was mentioned specifically or its creator named as having been attached to it. Even Variety‘s review, which refers in passing to the sequence, doesn’t mention its maker.

A lot of other viewers were impressed enough to try and find out who was responsible. DH1 was released in the US on November 19, and by the next day, Cartoon Brew posted a story on the subject: “A number of readers have written to ask who animated the shadow puppet-inspired ‘Tale of the Three Brothers’ sequence in the new Harry Potter film Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows. It was directed and designed by Ben Hibon who produced it in association with Framestore.” Surprisingly, it also turns out that the section of Framestore that normally makes commercials did the “Three Brothers” scene.

I spent some time tracking Hibon down, finding some good-quality frames to display here, and locating clips. There are a few interviews with Hibon, plenty of clips and entire shorts, and filmographies. The video quality of some of these clips is dreadful, though, and a lot of the stories one finds via Google are short, repetitive pieces.

Most of this material is not all that easy to find, so herewith a guide to where you can most usefully find information on someone who seems to be an up-and-coming talent.

Hibon has designed video games, made music videos and commercials, done a short “screen” for MTV, and directed a few shorts and a trailer for a feature, A.D., which seems still to be in progress. The fullest filmography is the official one on the website for Hibon’s own company, Stateless Films.

Animation and effects expert Bill Desowitz has interviewed Hibon for Animation World Network. That’s recent, December 3, and deals exclusively with the DH1 scene. On November 23, fxguide posted an interview with Dale Newton, the sequence supervisor for the piece. An older, undated interview with Hibon on It’s Art Magazine concerns the series of five two-minute shorts collectively known as “Heavenly Sword.” These relate to a video game of the same name that Hibon designed. This series is visually quite distinctive, but it’s a far more conventional work than the “Three Brothers” short, being heavily influenced by anime.

Also on November 23, indiewire posted a short background article on Hibon, with several videos. With one exception, which I’ll get to shortly, don’t watch these films here or on YouTube. Why? Because the Stateless Films site has most of them and more. Hibon’s clips are larger and better quality than anything else I checked, plus they’re displayed with a black screen and far fewer distracting graphics than on YouTube. Click on the Archives link to see older works, including samples of Hibon’s work on videogames.

His site is the only place where I found a full version of his ad for the French bank, Crédit Agricole. The point of the ad is that this is the first green bank. It’s a gorgeous piece, full of images of pollution and decay gradually giving way to scenes of places restored to their pristine state and new, clean technology in place. Here are some images, from a vertical descent downward through a series of jet-trails (at bottom), a shot in which a wall of identical canned goods suddenly flies away to reveal a street market with fresh produce on sale, and windmills replacing old factory chimneys that fly apart:

There’s a dream-like quality to the whole thing, with a lot of shots, many with rapid movement, juxtaposed with slow, stately music.

The indiewire clips linked above include two shortened, English-language versions of this ad, with Sean Connery appearing to make the message explicit. There are also some Crédit Agricole ads made by more conventional filmmakers. Watch one or two of those, and you’ll find the contrast dramatic.

None of these sites and others with Hibon clips or shorts has the “Three Brothers” sequence, not surprisingly. That is, YouTube has some horrendous, out-of-focus subtitled auditorium videos, made in perhaps a South American or Spanish theater. Avoid like the plague.

Framestore’s site has some information on Hibon’s sequence, and the only clip from it that I could find. It’s very small and too dark to render the subtleties of the visuals, but there it is. Framestore also animated the two house-elves, Dobby and Kreatur, and there’s some information on that part of the project as well.

The January, 2011 issue of Cinefex has a story on DH1 that will undoubtedly include a section on the “Three Brothers” animation, but I haven’t seen that yet.

One reason that there are so many short pieces on Hibon on the internet is that at almost exactly the same time, on November 22, Variety announced that the filmmaker had been signed to direct a long-dormant New Line project, Pan. It’s a variation on the Peter Pan story, with the roles of villain and hero being switched; here Captain Hook is a detective on the trail of a certain child-kidnapper. The studio acquired the project in 1996, and for a while it looked as though Guillermo del Toro would direct. This time the film might get made, since the Variety story reports that it’s being cast and should start shooting next fall.