My girl Friday, and his, and yours

Monday | January 16, 2017 open printable version

open printable version

DB here:

Criterion has just released a fine edition showcasing two classics of American cinema: The Front Page (1930) and His Girl Friday (1940). His Girl Friday is in a new HD restoration, and the earlier film, long crawling around in disgraceful public-domain bootlegs, now has a 4K glow–maybe looking better than it did at the time. The extra fillip is that it’s a version that director Lewis Milestone preferred to the familiar one.

Along with the films comes a host of features: interviews and shorts about Howard Hawks, Rosalind Russell, and the making of HGF, radio adaptations of both the Front Page play and the HGF film, a short about Ben Hecht, trailers, appreciative essays by Michael Sragow and Farran Smith Nehme, and a session with me about HGF.

Along with the films comes a host of features: interviews and shorts about Howard Hawks, Rosalind Russell, and the making of HGF, radio adaptations of both the Front Page play and the HGF film, a short about Ben Hecht, trailers, appreciative essays by Michael Sragow and Farran Smith Nehme, and a session with me about HGF.

Needless to say, I’d be plugging this release strenuously even if I weren’t involved. Long-time readers of this blog know that an early entry hereabouts talked about the diverse paths HGF took to becoming the classic it’s now recognized to be. I used the film in many courses I taught during my early days at Madison. Kristin and I have been writing about the film since then as well, first in Film Art (it still retains its place from the 1979 edition), then in Narration in the Fiction Film (1985) and On the History of Film Style (1998). Other references sneak into our entries here from time to time. The Criterion edition offered me another chance to rattle on about a movie I still, after nearly fifty years, love inordinately.

What can be left to say? Plenty, but today I’ll mention just two items. First, what is a Girl Friday? And second, how unobtrusively delicate can film style be?

More slop on the hanging

The phrase “girl Friday” comes, ultimately, from Robinson Crusoe, Defoe’s 1719 novel of how the castaway protagonist turned a cannibal prisoner into his servant: his man, Friday. The hapless convert to Christianity gained his name because Crusoe rescued him on a Friday. An 1867 children’s story, “Will Crusoe and His Girl Friday,” shows a little boy and girl planning to reenact Defoe’s tale, adding gender insult to racial and class injury.

“My Girl Friday” was a spicy 1929 play about flappers who drug tycoons at a party and then convince them that the worst has happened. Consisting largely of scenes with chorus girls in bathing suits, it was dubbed by Variety “out and out smut.” Unsurprisingly, it found success on Broadway. During some weeks its BO take rivaled that of The Front Page, on stage at the same time.

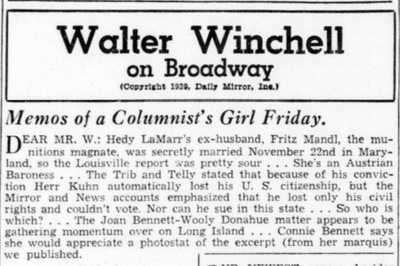

As far as I can tell, the phrase “girl Friday” became more prominent in American slang during the 1930s, thanks chiefly to columnist Walter Winchell (right, from Time 1938). At intervals from 1934 on, Winchell’s daily column carried the title “Memos of a Columnist’s Girl Friday.” The premise was that his secretary was an all-purpose newshound, gathering gossip and tidbits into a weekly memo to her boss. Evidently, Winchell’s secretary Ruth Cambridge (Mrs. Buddy Ebsen) didn’t write it. Under the “Memos” rubric Winchell could boast about his latest triumphs. His Girl Friday could ask innocently if “Mr. W.” saw the new Fortune poll of top columnists (in which he ranked high), or whether he noticed that several more newspapers had signed on to carry the column. Louella Parsons gave Winchell credit for publicizing the Girl Friday phrase.

As far as I can tell, the phrase “girl Friday” became more prominent in American slang during the 1930s, thanks chiefly to columnist Walter Winchell (right, from Time 1938). At intervals from 1934 on, Winchell’s daily column carried the title “Memos of a Columnist’s Girl Friday.” The premise was that his secretary was an all-purpose newshound, gathering gossip and tidbits into a weekly memo to her boss. Evidently, Winchell’s secretary Ruth Cambridge (Mrs. Buddy Ebsen) didn’t write it. Under the “Memos” rubric Winchell could boast about his latest triumphs. His Girl Friday could ask innocently if “Mr. W.” saw the new Fortune poll of top columnists (in which he ranked high), or whether he noticed that several more newspapers had signed on to carry the column. Louella Parsons gave Winchell credit for publicizing the Girl Friday phrase.

He started a brief feud when he smelled poaching. In 1937, two aspiring screenwriters sold MGM a story they called “My Girl Friday.” It involved, according to Daily Variety, “adventures of a newspaper circulation rustler.”

With Trumpian self-regard, Winchell asserted that he had popularized many catchphrases that Hollywood had bought as titles: “Blessed Event,” “Orchids to You,” “Is My Face Red?” “Okay, America,” and even “Whoopee.” In addition, he noted that MGM had spent a cool quarter of a million dollars to enhance a scene of The Great Ziegfeld. In the face of such largesse, Winchell felt justified in asking for compensation.

Therefore we think it would be ducky if MGM sent $10,000 to us for the use of “My Girl Friday,” which became better known via this dep’t.

Winchell hastened to add that he would give the money to charity. He pressed his case in several columns and in radio broadcasts. Paramount joined the fray, claiming that it acquired the title when it bought the old play, so MGM couldn’t use it anyway. At which point the Hays Office was consulted.

Using his Girl Friday voice, Winchell responded that he claimed only to have popularized the phrase, and in any case what was $10,000 to Hollywood, especially if the money went to charity? Muttering about how MGM’s song “Your Broadway and Mine” swiped the original title of his column, Winchell subsided, as did the dispute. MGM evidently never adapted the story in question.

Then, on 9 December 1939, Walter ran this.

No hard feelings from Winchell, apparently. He may have benefited from the association with the movie. During production and even after release, the film was sometimes called My Girl Friday. And the linkage of a Girl Friday to the newspaper game, be it gossip or circulation rustling, fitted the movie well, as it evoked Winchell’s rat-a-tat radio delivery and his near-prosthetic adhesion to phone receivers.

Yet Winchell mysteriously dropped the “Memos” rubric from his column in 1941. In the decades to come, many businessmen would claim to have a Girl Friday of their own. Maybe the film ultimately popularized the phrase more successfully than Winchell did.

For the waiter

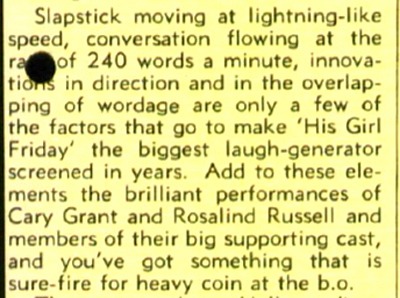

Daily Variety (5 January 1940), 3.

As a theatrical adaptation, His Girl Friday offers a challenge that Hawks accepted with ease. He had worked on films limited to a few interiors before, as with the train scenes of Twentieth Century (1934) and much of the airport action of Only Angels Have Wings (1939). He knew how to enliven situations unfolding in tightly confined settings.

Apart from enjoying the fast-paced comedy, you can learn a lot about film technique from the way Hawks energizes his static, prosaic surroundings. Take his resolutely unflashy staging in depth. It’s most apparent in the pressroom of the Criminal Courts Building, as I suggest in the supplement, but there are plenty of felicities of staging elsewhere. The most apparently unpromising example involves the restaurant where Walter Burns takes his ex-wife Hildy Johnson and her fiancé Bruce Baldwin. What to do with this simple set?

At a late point in the scene Walter will seek the help of the waiter Gus, who’ll call Walter to the phone. It’s a basic problem: How should the director prepare for that phase of the action? Hawks does it by setting up a zone of depth at the start of the scene, priming it quietly throughout, and paying it off when it’s needed.

Bruce, Walter, and Hildy enter the restaurant from the background. (Novice directors please note: No need for a sign saying, “Restaurant.”) The group comes to a table in the foreground. After some comic byplay as Walter grabs the chair next to Hildy, the three get seated and chat with Gus.

This framing orients us to the table and the rear area by the bar. We’ll never leave this general orientation on the scene. This commitment, far from being simply “theatrical,” makes for economy as the action develops.

In the course of the scene, Hawks activates the rear zone by having Gus come and go from it. Of course that area isn’t emphasized. Who’s likely to notice Gus giving the sandwich order back there when there’s patter and funny business to watch right in front of us?

In the course of the scene, Gus will come back to the table, pouring water, delivering sandwiches, and getting kicked in the shin by Hildy, who’s aiming at Walter. Throughout, we’re quietly primed for that alley of space behind Walter to be occupied by Gus.

The priming pays off when Walter, realizing that he has to prevent Hildy’s taking the train today, deliberately spills water in his lap.

Walter pivots and heads to Gus, who’s back there in his domain, waiting to be pulled into the plot. He’ll summon Walter to the fake phone call.

No big deal–certainly not as eye-catching as the dazzling comedy around the table. But the care for such little things is the mark of a craftsmanship that uses space compactly, without fuss. No need for camera angles that show the fourth wall (or even walls two and three). No need to build more of the set on the side; this is Columbia, after all. Just let reliable Joe Walker light that background enough to keep us aware of it (out of focus for most of the scene) and then activate it when you need it.

Hawks was obeying the advice Alexander MacKendrick would later give:

Within the same frame, the director can organize the action so that preparation for what will happen next is seen in the background of what is happening now.

Or as Hawks put it in 1976:

You know which way the men are going to come in, and then you experiment and see where you’re going to have Wayne sitting at a table, and then you see where the girl sits, and then in a few minutes you’ve got it all worked out, and it’s perfectly simple, as far as I am concerned.

The unstated premise is indeed perfectly simple: You don’t need to show more space than the physical action requires. It’s a rare premise today.

How long is it?

This sort of priming fits neatly into a cinema based in continuity–dramatic, spatial, temporal. Hawks is a master of staging action so that it flows unobtrusively. At times, though, it’s fun to spot some discontinuities, and editing is a good place to look.

Ozu is, to my knowledge, the only director who invariably creates perfect match-cuts on action. Even Hawks has to cheat things a bit to make the editing flow. (Hildy’s pitching of her purse is an example I use in the commentary.) But consider how Hawks can get a spark out of a small, mismatched action.

We’re still in the restaurant, and Walter has persuaded Hildy to cover the Earl Williams story in exchange for buying an insurance policy from Bruce. Talking of his upcoming physical, Walter boasts, “Say, I’m as good as I ever was.” Hildy fires back, “That was never anything to brag about,” and Walter reacts and turns his head. As he turns, we get these two shots.

At first Walter is stunned, apparently readying a reply; but at the cut, he’s sporting a grin. It’s partly a grin of triumph, showing that he’s gotten Hildy to do his bidding, but it’s also an appreciation of her wit: a sort of “That’s my girl” pride in her fast comeback. Strictly speaking, the cut’s a mismatch, but the instantaneous switch in reaction gives the scene double value.

Finally, there’s framing. The rugged outdoor guy Hawks is as delicate as they come when it’s a matter of frame corners and edges, and his sense of pictorial balance is fastidious. Go back to the long opening scene in Walter’s office, when he and Hildy are going through the preliminaries. They size each other up before Walter sits down in his swivel chair.

A slight track forward has planted Walter in the lower corner of the frame. A cut in to Hildy’s reaction (not shown) enables a transition to a slightly different framing. That setup allows Walter to invite her onto his knee, which pokes up from the bottom edge.

Joe Walker has obligingly edge-lit that stretch of pant leg, and it’s about the only thing moving in the shot, so we can’t miss Walter’s come-on.

Now Hawks does something very pretty. Hildy moves to the table and perches on it. Hawks reframes with her, but keeps the shot oddly unbalanced, with Walter resolutely facing the area she’s not in.

A sort of spatial suspense develops. Hawks sustains this odd framing while Walter picks up a cigarette, tosses one to Hildy, lights up, and tosses her a match. Fairly deliberately too, in what’s supposed to be Hollywood’s fastest movie.

When both are smoking comfortably, Walter swivels his chair to snap his head into the lower left corner, which has been waiting for him all along. The simple movement provides the scene’s new beat, which starts with Walter’s line: “How long is it?” I haven’t yet mentioned that this is a fairly dirty movie, but you knew that.

The shot began with the actor’s head in the lower right, developed with that head poised midway in the frame, and now ends with the head cocked in the lower left. What looks like sterile geometry feels, on the screen, perfectly unforced. And lest we misread the “How long is it?” Walter innocently explains, in a medium shot, that he’s just wondering how long it’s been since they’ve seen each other. That in turn calls up an over-the-shoulder reverse angle, and the next phase of the scene is off and running.

At this point in film history, the cinematographer, while shooting, could not see exactly what the lens was taking in. The careful unbalancing and rebalancing of the shot had to be achieved through a mixture of expertise and intuition. The same thing with keeping Gus in reserve back there by the bar, and letting an incompatible take of Grant’s reaction stay in after a cut. It’s all perfectly simple, as far as I’m concerned.

Thanks to Kim Hendrickson, Grant Delin, and Peter Becker of Criterion for inviting me to spend more time with this splendid movie. Hawks’ quotation about keeping it simple comes from my On the History of Film Style (Harvard University Press, 1997), 149.

You can find background here on the restoration of The Front Page, supplied by Academy archivists Mike Pogorzelski and Heather Linville.

You can get a sampling of Winchell’s radio delivery from the period here, complete with nervous teletype clackings serving as transitions. For more background on HGF, go here. That entry observes the usefulness of the film’s lines in many situations. In this respect it resembles another Hawks film, that repository of worldly wisdom known as Rio Bravo.

Gus the waiter is played by the inimitable Irving Bacon, one of a dozen or so outstanding supporting players. This is another of the film’s triumphs: Regis Toomey, Porter Hall, Gene Lockhart, Abner Biberman, Roscoe Karns, and other memorable character actors all seem to be having fun. And Billy Gilbert as the wayward Pettibone is the friendliest deus ex machina in Hollywood cinema.

Finally, do audiences today know the meaning of Hildy’s flipped hand in response to one of Walter’s catty remarks? Has nose-thumbing gone out of popular culture? Apparently not.

P.S. 4 February 2017: On the Parallax View site, Sean Axmaker has the most in-depth appreciation of this edition of The Front Page I’ve seen online. And he has plenty to say about HGF too.

P.S. 2 February 2018: His Girl Friday is now streaming on FilmStruck, and among the bonus materials is the video essay I mention.

His Girl Friday (1940).