How to tell a movie story: Mr. Stahr will see you now

Sunday | January 5, 2014 open printable version

open printable version

DB here:

It is 1935. Mr. George Boxley is a prominent writer who has been brought to Hollywood. He is working with two other screenwriters on a story, but he feels angry and dissatisfied. His collaborators ruin his contributions, and when he writes solo he produces “interesting talk but nothing more.” He has come to the head of production to complain, and beneath his annoyance lies a mild contempt for the movie craft.

He has tried to adjust his standards to movies, he explains, by having his dialogue delivered while his characters are dueling. At the end of the scene one falls into a well and has to be hauled up again.

The studio chief, Monroe Stahr, asks if Mr. Boxley would include such a scene in a book of his own.

“Naturally not.”

“You’d consider it too cheap.”

Boxley replies: “Movie standards are different.”

“Do you ever go to them?” Stahr asks.

“No,” confesses the parvenu screenwriter. “Almost never.” He explains, defensively, that movies are full of things like duels and falling down wells “and wearing strained facial expressions and talking incredible and unnatural dialogue.”

“Skip the dialogue for a minute,” said Stahr. “Granted your dialogue is more graceful than what these hacks can write—that’s why we brought you out here. But let’s imagine something that isn’t either bad dialogue or jumping down a well. Has your office got a stove in it that lights with a match?”

“I think it has,” said Boxley stiffly, “—but I never use it.”

Mr. Boxley is about to get a tutorial in how to tell a movie story.

Behind the glitter

F. Scott Fitzgerald

There have been novels about Hollywood as long as the movie industry has been there. Most have been either straightforward wish-fulfillment (girl/boy from the sticks makes it big) or cautionary tales (boy/girl fails or becomes depraved). The more ambitious “Hollywood novel” has been more sour and sweeping. It presents itself as a harsh exposé that makes a broad social comment on picture-makers, their public, and the society that spawns both.

This serious Hollywood novel is largely a creature of the late 1930s. Wedding hard-boiled style to Depression-era realism, Nathanael West’s Day of the Locust (1938) and Horace McCoy’s I Should Have Stayed Home (1938) present stark, aggressively despairing accounts. In these books, Hollywood is America, only more so.

Both West’s and McCoy’s books fared poorly in the market. The triumph was Budd Schulberg’s What Makes Sammy Run? (1941), which found in the rapacious Sammy Glick a prototype of the modern entertainment entrepreneur. Schulberg daringly emphasized the fact that Sammy was a Jew, creating a controversy that lasted for quite a while.

The booming movie market of the war years, along with the fact that more novelists found themselves involved with the studios, made the 1940s something of a golden age of the Hollywood novel. The movie kingdom became the setting for dozens of murder mysteries, veiled memoirs, and satires—some written by practicing screenwriters. (Among the most notable: Ben Hecht’s offhand but heartfelt I Hate Actors!, 1944). At a higher level of literary prestige, there were two 1948 titles from Englishmen, Evelyn Waugh’s caustic The Loved One and Aldous Huxley’s Ape and Essence, a novel written as a pseudo-screenplay. But none of these finished works won the enduring fame of an incomplete story published in the same year that Schulberg introduced Sammy Glick.

Built on the grand scale

Irving Thalberg.

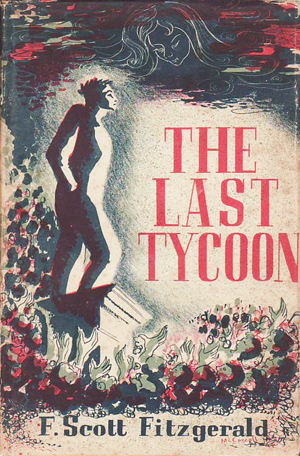

In 1939 F. Scott Fitzgerald had begun The Last Tycoon (perhaps intending to call it The Love of the Last Tycoon: A Western). By then his brief screenwriting career was over, but he was fascinated by MGM’s boy wonder Irving Thalberg, “one of the half-dozen men I have known who were built on the grand scale.” Fitzgerald decided to center his plot on Monroe Stahr, a Thalberg-like producer.

Stahr is a shrewd, intellectually gifted workaholic who is an expert in manipulating what is coming to be a new system of moviemaking. Brisk and efficient in the office, Stahr is occasionally cold and arrogant, but his primary trait is a remarkable sensitivity to the emotional temperature of each situation. He gains our sympathy because in private Stahr is sunk in melancholy, longing for his dead wife and hoping to find another woman to love.

When Fitzgerald died in 1940, he had completed less than half of The Last Tycoon. His long-time friend, the critic Edmund Wilson, assembled an edition that was issued in 1941, with the finished portions supplemented by notes and a five-act outline. The book had a great impact. The New York Times reviewer commented:

Uncompleted though it is, one would be blind indeed not to see that it would have been Fitzgerald’s best novel and a very fine one. Even in this truncated form it not only makes absorbing reading; it is the best piece of creative writing that we have about one phase of American life—Hollywood and the movies.

Matthew J. Bruccoli, who has brought out the authoritative edition, remarks:

Even in its preliminary and incomplete condition, The Love of the Last Tycoon is regarded as the best novel written about the movies.

Reading the book for my research on the 1940s, I became fascinated by its understanding of what we might call the Hollywood aesthetic.

That understanding begins with a recognition of the production process. Most Hollywood novels mention actual stars and directors, but The Last Tycoon goes beyond name-dropping. It takes us into the offices, the editing rooms, and onto the set when Stahr must fire a director. These scenes have an authority that most novels lack, assisted by Fitzgerald’s effort to present his mogul not as a monster but as a man of genuine, if sometimes dictatorial, charm, tact, and taste.

Setting his novel in 1935, Fitzgerald also registers how studio organization shifted toward a central-producer system. Stahr deliberately avoids learning the details of camerawork, editing, and sound.

He could have understood easily enough—often he preferred not to, to preserve a sensual acceptance when he saw the scene unfold in the rushes. . . . His function was different from that of Griffith in the early days, who had been all things to every finished frame of film.

One of Fitzgerald’s most cryptic notes indicates his recognition of different studio styles.

The Warner Brothers narrative writing and the Metro dramatic, packed—cut back and forth writing from Stahr.

This might be a reference to Warners’ vivacious montage sequences, which were sometimes considered “narrative,” while fully enacted scenes were called “dramatic.” The use of “cut back and forth” here exemplifies Fitzgerald’s occasional use of movie slang in his notes, as when he gets his characters on the Super Chief passenger train:

In a very short transition or montage, I bring the whole party West on the chief.

Like many intellectuals of his time, Fitzgerald was fascinated by the movies as an artistic medium. The standard version of film history was articulated in many books of the period, most notably Lewis Jacobs’ Rise of the American Film (1938). Fitzgerald dots his novel with commonplaces about the history of cinema.

She was reputed to have been on the set the day Griffith invented the close-up!

[Stahr] prepared for the meeting [with the Writers Guild] by running off the Russian Revolutionary Films that he had in his film library at home. He also ran off “Doctor Caligari” and Salvador Dali’s “Un Chien Andalou,” possibly suspecting that they had a bearing on the matter.

Astonishingly, Fitzgerald even considered calling his novel The Lumière Man.

Most original, I think, is the episode I’ve started to present to you. It’s an exemplary scene, showing how good Stahr is at his job. He subtly steers Mr. Boxley, the East Coast littérateur, toward returning to the screenplay. But he also tutors Mr. Boxley, and us, in a deeper awareness of how classical Hollywood aimed to tell its stories.

Just making pictures

Imagine, Stahr tells Boxley, you’re sitting in your office, tired out.

A pretty stenographer that you’ve seen before comes into the room and you watch her—idly. She doesn’t see you although you’re very close to her. She takes off her gloves, opens her purse, and dumps it out on the table.

Stahr continues. From her change, the young woman picks out a nickel and puts it on the desk. She picks up a matchbox and then takes her black gloves to the stove. She puts them inside the stove and starts to light it, when the phone suddenly rings.

The girl picks it up, says hello—listens—and says deliberately into the phone, “I’ve never owned a pair of black gloves in my life.”

The stenographer hangs up and kneels by the stove again.

Just as she lights the match you glance around very suddenly and see that there’s another man in the office, watching every move the girl makes.

Stahr pauses.

“Go on,” said Boxley smiling. “What happens?”

“I don’t know,” said Stahr. “I was just making pictures.”

Boxley feels he’s been wrong-footed.

“It’s just melodrama,” he said.

“Not necessarily,” said Stahr. “In any case nobody has moved violently or talked cheap dialogue or had any facial expression at all. There was only one bad line, and a writer like you could improve it. But you were interested.”

Question time

Throughout the 1930s, critics like Otis Ferguson praised American studio pictures for their clean, straight storytelling. The primary concern of Fritz Lang, for instance, “is with the rightness and immediacy of each fragment as it appears to you, makes its impression, leads you along with each incident of the story, and projects the imagination beyond into things to come.” I think that Stahr’s tutorial helps us understand how that blend of immediacy and flow, vivid moments and keen anticipation, works.

For one thing, the gloves scene doesn’t fit certain clichés about Hollywood. It isn’t spectacular; it’s not a chase or a fight or a seduction or a slapstick episode. As Stahr points out, nobody is dueling or falling down a well.

We often say that Hollywood movies emphasize plot (lots of action) over character (stereotyped, at that). But this scene doesn’t have much action, and we don’t know anything about the character. (We can’t even be sure she’s lying; maybe these gloves aren’t hers.) What we have is plot and character fused in a situation. The scene creates, out of mundane materials, a crisis.

We say that Hollywood films grab us through emotion. Do we feel strong passions here? Well, not so much. We say that Hollywood films make us identify with the characters. Are we identifying with the young woman, or the magically unseen Boxley, or the man suddenly revealed watching the whole thing? Not really. The paramount emotion, as Stahr points out, is that diffuse, low-level one we call interest.

What does grab us, I think you’ll agree, are the questions that are implicit in the action. Why does the woman leave a nickel on the desk? Why does she start to burn the gloves? Why does she deny owning black gloves? Why is the man watching her? And what will happen next?

Noël Carroll has developed a theory of narrative he calls “erotetic.” Telling a story, he suggests, creates a controlled cascade of questions. Sometimes they pile up, as here; sometimes a question is answered but the answer raises another question. Stahr’s lesson supports Carroll’s idea that in any art, narration is a matter of asking, postponing, and answering questions. Erotetic principles, Stahr suggests, are more central to Hollywood storytelling than obvious appeals like spectacle and gags.

Another narrative theorist, Meir Sternberg, has proposed that the “master effects” aroused by stories are curiosity, surprise, and suspense. Curiosity is a matter of wondering about what led up to the actions we’re seeing now. What has impelled our stenographer to burn these gloves? Surprise comes from revealing a gap in the telling’s continuity. This occurs when Stahr’s “pan shot” (“you glance around very suddenly”) reveals a man in the office watching her efforts. If curiosity involves the past, and surprise punctuates the present, suspense points us forward: What will happen next? Stahr’s anecdote breaks off just as we learn that the man is watching. Will he prevent her from burning the gloves? More generally, how will he figure in the plot to come? Sternberg’s three cognitive attitudes, which he considers fundamental to narrative engagement, are neatly wrapped up in Stahr’s toy example.

Every writer knows that coming up with a grabby scene is easy. The problem is paying everything off. So admittedly, Stahr has dodged the work of figuring out the whole plot. Nonetheless, his example should clarify one notion of Hollywood storytelling. Relatively easy to shoot (Mr. Boxley, close to the woman but mysteriously unseen, is obviously the camera), but demanding skill in pacing and performance, the scene shows, I think, the unpretentious power of that clean storytelling that Ferguson and his peers celebrated.

The intellectuals who throughout the 1930s and 1940s derided Hollywood as simple-minded and uncreative didn’t really drill down into the specifics of how the storytelling system worked. Fitzgerald did, perhaps because as a novelist he could observe and appreciate the craft of it—even if he couldn’t actually succeed at it himself. The Last Tycoon is a nuanced tribute to Hollywood as an aggressive business that need not necessarily suffocate richness of personality. It’s also a modest tribute to the power of a storytelling model that is only apparently obvious.

“What was the nickel for?” asked Boxley evasively.

“I don’t know,” said Stahr. Suddenly he laughed. “Oh yes—the nickel was for the movies.”

I’ve drawn my quotations of Fitzgerald’s working drafts from both Edmund Wilson’s 1941 edition of The Last Tycoon and from Matthew J. Bruccoli’s 1993 edition of The Love of the Last Tycoon: The Authorized Text. Each version contains many intriguing jottings that aren’t included in the other one. Quotations from the main text come from Bruccoli’s edition, except that I’ve corrected Fitzgerald’s misspelling of “nickel.”

I’ve been guided by Anthony Slide’s excellent bibliographical survey, The Hollywood Novel: A Critical Guide to Over 1200 Works (McFarland, 1995). See also Budd Wilson Schuberg’s portmanteau review, “Literature of the Film: The Hollywood Novel,” Films 1, 2 (Spring 1940), 68-78.

Janet Staiger explains how Thalberg, a prototype of the central-producer system during the 1920s, was gradually embracing the newer division of labor, that of the producer-unit system, in the early 1930s. See her chapter 25 in the book she wrote with Kristin and me, The Classical Hollywood System: Film Style and Mode of Production to 1960.

Noël Carroll’s theory of erotetic narration is explained in several of his publications; a convenient one is The Philosophy of Horror, chapter 3. For Meir Sternberg’s account of curiosity, suspense, and surprise, see his “Telling in Time” series in Poetics Today (Winter 1990, Fall 1992, and Spring 2006).

J. Donald Adams’ review of The Last Tycoon is in The New York Times (9 November 1941). My quotation from Otis Ferguson comes from “Fritz Lang and Company,” The Film Criticism of Otis Ferguson, ed. Robert Wilson (Temple University Press, 1971), 372.

An earlier entry on Ferguson further develops his ideas about the clean contours of Hollywood storytelling.

Elia Kazan’s film of The Last Tycoon includes the Boxley scene. Apart from adding unnecessary lines, it’s an exercise in ham, with other characters watching Boxley’s discomfiture and a smug Stahr (Robert De Niro) dashing about the room and pantomiming the action. Kazan’s Stahr burlesques the story situation he invokes, whereas I take the novel’s scene as a playful but sincere object lesson.

Stahr shows Boxley the black gloves in Kazan’s Last Tycoon.