Archive for the 'Tableau staging' Category

The raptures of rigor: Roy Andersson’s ABOUT ENDLESSNESS at Venice 2019

About Endlessness (Roy Andersson, 2019).

DB here:

In the midst of the frenzy of fast cutting in films of the 1990s, a few directors reminded us of the virtues of simply putting your camera on a tripod and letting the action unfold in front of it. Abbas Kiarostami, Hou Hsiao-hsien, Kitano Takeshi, Tsai Ming-liang, and several other filmmakers reminded us that the fixed camera and long take, i.e. the “theatrical” cinema so despised in the 1920s and 1930s, still harbored great expressive resources.

It’s a lesson we have to keep learning–with Warhol and Tati in the 1960s, Akerman and Duras and Angelopoulos in the 1970s, Iosseliani in the 1980s, and not least with one of the greatest exponents of the tendency, Manoel de Oliveira. His 1963 film Rite of Spring initiated his persistent, endlessly inventive exploration of the tableau shot. Doomed Love (1978; briefly discussed here) is a superb example; Francisca (1981) is another, and we were lucky to catch a superb restoration on display in the Venice Classics section. I hope to write about it soon!

After four years of production, Roy Andersson’s Songs from the Second Floor was released in 2000 and established his distinctive approach to the tableau tradition. Since then he has made only three features, the most recent of which played in competition at Venice 76. Of course we had to see it, and to visit his press conference.

This is visionary cinema of a unique kind.

Landscapes of unhappiness, minor and major

Start with some brute facts. About Endlessness runs only seventy minutes (without credits), and it consists of 32 one-shot scenes. As in Andersson’s other films since 2000, most scenes stand alone, without narrative connection to others.

Some are bare-bones situations, as when a young man watches a young woman watering a plant, or when a father ties his little girl’s shoe in a rainstorm. Others unfold a dramatic crisis. A man bursts into tears on a city bus, complaining that he doesn’t know what he wants. A dentist, put off by a patient’s yowls of pain, simply walks out of the consultation and ends up in a bar.

Some shots draw on our knowledge of a broader story, as when Hitler stalks into one chamber of his bunker and his lieutenants, exhausted by the bombardment, sporadically salute him. He hardly seems to notice. A few tableaux present a recurring thread, like minimalist running gags. A man recognizes a schoolmate, but wonders why the man won’t greet him. A priest feels himself losing his faith, gets drunk while celebrating mass, and consults a doctor for advice. And one recurring image shows a woman cradled in a man’s arms floating in the sky–at one point drifting over the ruins of the bombed Cologne of World War II.

What makes Andersson’s cinema so fascinating is his effort to design intricate, gradually unfolding compositions that harbor powerful emotional expression. Dialogue is at a minimum; objects are arranged with the precision of still lifes. His people are often doughy and plodding, with hangdog expressions and complexions like pumice, living in a world dominated by grays and pastel browns. His movies reveal how many shades of beige there can be.

The grandeur of the distant framings accentuate the impotence of the characters. These sad creatures are caught in strict, unsympathetic perspective, all sharp angles and endless vistas. They stand exposed by flat, minimally sculptured lighting. “I avoid shadows,” he explained at the press conference. “I want to make pictures where people can’t hide. A light without mercy.”

The same mercilessness is seen in the settings, which may look fairly naturalistic but are wholly artificial. Andersson uses miniatures, background painting, and digital effects to create his picture-book landscapes. Streets, cities, train platforms are all the product of years of preparation. Like Tativille in Jacques Tati’s Play Time, Andersson’s sets create a beguilingly realistic version of a wholly fake city.

The sets are calculated to make sense from a single vantage point, as Renaissance paintings are. In a shot like the first one below, moving the camera would reveal the forced-perspective buildings outside.

Some of these landscapes are as eerie as de Chirico’s, but without any of the sensuous shading.

Which means that posture, gesture, and objects near and far have to carry the drama, however anecdotal it may be. The man who thinks his old friend has snubbed him tells us that the friend has a Ph.D. His wife consoles him (after all, they’ve been to Niagara Falls), but he’s still anxious. His puzzled fretfulness is carried by his slumped bearing, his plaintive expression, and his clinging to his slotted spoon. Meanwhile we hear his pasta simmering ever more loudly in the kettle in lower frame right, a light objective correlative to his annoyance.

Andersson teases us by letting us imagine how a micro-story might unfold. In a cafe, a woman sits alone, with no drink in front of her. She’s in the classic posture of waiting, A man eats dinner behind her (his cutlery clinks) and an empty table on far right bears the traces of another customer. In comes a large, lumpish fellow brandishing a bouquet. He hesitantly asks for Lisa Larsson. So it’s a rendezvous?

Nope. A bald man enters from frame left bearing two beers.

The lady doesn’t admit to being Ms. Larsson. Maybe she really isn’t, or maybe she found a better date. In any case, the newcomer turns and leaves, a bit sadly. Of course, there’s always the possibility that the absent customer on the right was his date. We, and he, won’t know.

Note, in passing, Andersson’s use of classic staging techniques. Tableau cinema needs to guide our attention through pictorial tactics such as central placement, frontal positioning, and patterns of blocking-and-revealing. By giving the bald man a central position in the format and letting him mask our view of the man eating in the corner, Andersson makes sure we’ll register the confrontation between him and the intruder.

Most of the tableaux are accompanied by a brief voice-over, a woman saying, “I saw…” followed by a single-sentence description of the action. Andersson claims to see her as a bit like Scheherazade, but she has as little commitment to a full story as he does. Her narration provides very little judgment on the scene but does supply a bit of information–often grim, as when we learn that a busker lost his legs in combat.

Indeed, war is a recurring motif in the film, making it bleaker than any of the other Andersson films I recall. Now the minor miseries and absurdities of modern life sit along a continuum of death and destruction. A sequence of spontaneous dance here, a father’s awkward love for his daughter there–these don’t wholly compensate for a wartime execution or the bombing of Dresden. The gags are fewer now, and Andersson’s fantastical but stubbornly tangible cities have never looked more oppressive. The idea of endlessness stretches in many provocative directions: the infinite vistas of city and sky, the pinpricks of guilt and frustration in everyday life, the obscene endlessness of war. Lucky are those who can in a gentle embrace float above it all.

Andersson’s last film, A Pigeon Sat on a Branch Reflecting on Existence, won the Golden Lion for Best Film in Venice in 2014. Maybe this one will too? It’s one of the best new films I’ve seen here this year. More on the others, in later entries!

Thanks to Paolo Baratta and Alberto Barbera for another fine festival, and to Peter Cowie for his invitation to participate in the College Cinema program. We also appreciate the kind assistance of Michela Lazzarin and Jasna Zoranovich for helping us before and during our stay.

We’ve written bits on Andersson’s films elsewhere in our blog entries. See our entries on tableau staging for lots more on how this stylistic approach works. I discuss the technique as well in On the History of Film Style and Figures Traced in Light: On Cinematic Staging.

To go beyond our Venice 2019 blogs, check out our Instagram page.

About Endlessness (2019).

Sometimes an actor’s back…

Il Maschera e il Volto (1919).

…can crisply punctuate a scene.

DB here:

One of the 1919 films on display at Cinema Ritrovato this year was Augusto Genina’s Il Maschera e il Volto (The Mask and the Face, 1919). It’s drawn from a popular play that satirized the erotic stratagems of the elite. The movie begins by introducing a gaggle of couples at a Lake Como house party, so I expected that it would create interlocking intrigues in the manner of silent-era Lubitsch films like The Marriage Circle (1924). Not so: the plot concentrates on one romantic triangle. The version we have, at 1799 meters, might be a little shorter than the original (said to be around 1900 meters), but it seems likely that the plot we have dominated the initial release too.

Savina is betraying her husband Paolo with the family lawyer Luciano. During the house party Paolo declares that a cuckolded husband has every right to murder the unfaithful wife. When he learns of Savina’s affair (but not Luciano’s complicity), he orders her to leave the household immediately. Paolo declares that she will become dead to him and their friends.

Paolo tells Luciano that he killed Savina. We get a lying flashback (yep, already and again) that shows him strangling her and dumping her body in the lake. Savina overhears his false confession. When she hears Luciano asserts that she got what she deserved, she realizes he’s worthless. Disillusioned about both of the men in her life, she follows Paolo’s order and leaves their estate.

Of course a woman’s corpse, face mutilated, is soon found in the lake. Now Paolo must stand trial for Savina’s murder, and Luciano must defend him.

Not the funniest comedy I ever saw, but it has a grim charm. One particular scene made me happy.

Piano ensemble

Readers of this blog know that I like to study staging in 1910s films, and Genina provided nifty examples in the 2017 Ritrovato season. Like the Lupu Pick film I reviewed at this year’s jamboree, Il Maschera lies stylistically midway between pure tableau cinema and editing-driven construction. Interior scenes are often broken up by many cuts, but they’re typically axial, straight-in and straight-back, without reverse angles. (The exception is the trial scene. As in many 1910s films, it creates a more immersive space through “all-over” cutting.) In most scenes, the shots enlarge actors to follow their responses, but we don’t get setups that penetrate the space, putting us inside the flow of action.

Still, axial cuts, as Eisenstein and Kurosawa and John McTiernan knew, have a peculiar power. They can be abrupt and punchy, or more subtle in readjusting the framings. The latter option is on display in the film’s first big scene, when all the guests gather in the salon around the piano.

The scene runs about two and half minutes and consists of twelve shots and six dialogue titles. What’s worth noticing is the slight variations in setups, coordinated with what Charles Barr has felicitously called “gradation of emphasis.” Often the changing setups are masked by an inserted dialogue title, so there are no bumps in continuity.

The orienting view is a bustling shot that piles up faces and shoulders along the horizontal axis.

In an axial cut-in, the guests debate the righteousness of Othello’s murder of Desdemona. A further cut-in shows Luciano and Savina on the far right sharing glances. (The curly-haired woman will prove an innocent witness.) It’s a Hitchcockian situation, but without the POV singles.

Soon an older husband rises from his chair in the rear (another cut-in, “through” the group) and comes forward to join them. He draws alongside the husband to calm him down.

I’ve talked about crowded tableaus like this before. The Americans I survey were somewhat bolder than Genina in jamming the heads even closer together, creating partial faces that float out of the background. Genina has, however, other goals in view.

The woman in white

During the cut-ins, Genina takes the opportunity to rearrange the actors around the piano and re-scale his shots. There are five distinct variants of the piano grouping; even setups that might seem the same aren’t quite. There are two setups of the adulterous couple. All these are calibrated to suit the action presented.

For instance, when Paolo launches his rant about unfaithful women, the framing is tighter to favor him, and the foreground woman in white is primed for her big moment.

Similarly, the second cut to the adulterous couple is framed somewhat differently from the earlier one (on left), with Luciano pushing aside the cute curlyhead. He and Savina are listening more intently to Paolo’s denunciation of faithless wives.

So what seem to be fairly straightforward repetitions of setups are in fact minutely adjusted to favor certain actions. This strategy allows Genina to return to the whole ensemble.

In a closer view, the woman in white suggests that they stop arguing about infidelity and go in to play cards. She rises, blotting out Paolo in mid-rant.

The effect would be less pointed if she were in black like the other women.

Everyone but the older husband turns away, and people retire to the next room in the distance. They drain the space like water emptying out of a tub. That leaves what filmmakers today would call the scene’s button: the old man noticing that Luciano and Savina don’t join the group. Throughout the scene they’ve been literally marginalized on the far right.

It’s through this older man we just barely see the couple leave. He seems to understand the game they’re playing. and now he watches them disappear, perhaps to a private rendezvous.

The scene ends with another turning from the camera, another actor’s back letting us know the action is done.

Very often, turning from the camera signals the end of scenes, and of films.

It would have been fairly easy for any director to simply let the actors clustered around Paolo drag him off to play cards. But by having the woman in the foreground pop up, cut off our view of Paolo, and trigger a general exit Genina makes the action taper off briskly. Staging in the silent cinema is full of such little felicities, and it’s one job of criticism to appreciate them. It’s especially important since such techniques seem no longer part of filmmakers’ skill sets.

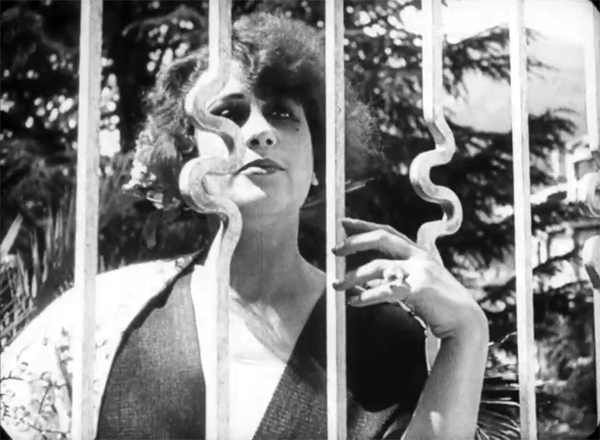

Then again, some Maschera images just whack you in the eye. Who doesn’t sense passion, elaborately caged, in the image below?

Thanks as usual to the Cinema Ritrovato Directors: Cecilia Cenciarelli, Gian Luca Farinelli, Ehsan Khoshbakht, Mariann Lewinsky, and their colleagues. We particularly owe Mariann for her curating of the Hundred Years Ago series every year. Special thanks as well to Guy Borlée, the Festival Coordinator.

Information about La maschera e il volto can be found in Vittorio Martinelli’s Il Cinema Muto Italiano: I film del dopogerra/1919 (Rome: Bianco et nero, 1960), 170-172.

Other Sometimes... entries consider a single axial cut, a shot in depth, a jump cut, a reframing, and a production still.

Il Maschera e il Volto (1919).

A hundred years ago, and less, at Cinema Ritrovato ’19

DB here:

Hundreds of films, thousands of passholders, sweltering heat (105 degrees Fahrenheit on Thursday). Dazzling tributes to Fox films, Youssef Chahine, Eduardo De Filippo, Henry King, Felix Feist, silent star Musidora, sound star Jean Gabin, and other themes. Many filmmakers from Africa, South Korea, and Europe, as well as master classes with Francis Ford Coppola and Jane Campion.

Yes, Cinema Ritrovato is on steroids this year.

And as we always say: There are so many tough, indeed impossible, choices. Kristin has been faithfully following the African series, while I’ve hopped between restored and rediscovered Hollywood classics and the films from 1919. Today I’ll report a bit on the latter, with an addendum on a major filmmaker’s ave atque vale.

1919 bounty

Song of the Scarlet Flower (1919). Production still.

By the end of the 1910s, the feature-length format had become well-established, and a bevy of directors in Europe and America were launching their careers. Abel Gance, Victor Sjöström, Mauritz Stiller, John Ford, Raoul Walsh, Cecil B. DeMille, Lois Weber, Charlie Chaplin, Douglas Fairbanks, William S. Hart, Mary Pickford, and many other figures had already made impressive work. 1919 brought us some outstanding titles. There was von Stroheim’s Blind Husbands, Griffith’s Broken Blossoms and True Heart Susie, Lubitsch’s Madame DuBarry, along with the lesser-known Victory of Maurice Tourneur, the first part of Sjöström’s Sons of Ingmar, and the overbearing, delirious Nerven of Robert Reinert.

Bologna showed none of these. Its massive 1919 lineup featured some classics in restorations, notably Capellani’s The Red Lantern (starring Nazimova), Dreyer’s debut The President, and Stiller’s Herr Arne’s Treasure. As a sidebar there was the 1919 Italian serial I Topi Grigi, a fun sub-Feuillade exercise in crooks and chases with some nifty shots. And there were a great many fragments and short films from that year, including a Hungarian entry by Mihály (Michael) Kertész (Curtiz).

Less known than Stiller’s official classics is The Song of the Scarlet Flower, a wonderful open-air drama about a young farmer’s wanderings and his heart-rending romances with three women. In a new digital version, it emerged as one of the most sheerly beautiful films I saw at Bologna. The central action sequence, in which the hero dares to ride a log through rapids to the very edge of a waterfall, gained even greater tension thanks to the swelling orchestral score by Armas Järnefelt–the only original score to be preserved for a Swedish silent.

1919, German style

Der Mädchenhirt (The Pimp, 1919). Production still.

Then there were two remarkable German films unknown to me, both by directors better known for later work. Der Mädchenhirt (The Pimp) was by Karl Grune, most famous for The Street (Die Strasse, 1923). The plot follows a shiftless young man who casually becomes a pimp and pulls women into prostitution. Introducing the film, Karl Wratschko pointed out that many Weimar films warned of sexual misbehavior, and certainly the young hero of this film gets ample punishment for his sins.

Stylistically, Der Mädchenhirt was typical of much European cinema of the late ‘teens, when the tableau style, which promoted intricate staging with few analytical cuts, was losing force. Grune mostly handles action in ensemble shots broken up by axial cuts to closer views. If German filmmakers weren’t quite as editing-prone as other European directors, that may be because they didn’t have access to American models. Not until January 1920 were Hollywood films of the war years imported into Germany.

Another film carried this moderate continuity style to an intriguing extreme. Tötet nicht mehr! (Kill No More!) framed a plea against capital punishment within a family drama. Sebald, the son of a by-the-book prosecutor, falls in love with the daughter of a former prisoner. When Sebald is cast out by his father, the couple take up a theatrical career playing Pierrot and Colombine. But then Sebald blocks the theatre director from seducing his wife, so the director blackballs them and they can’t get work in other shows. Visiting the director, Sebald quarrels with the man and kills him. He’s arrested, tried, and sentenced to death.

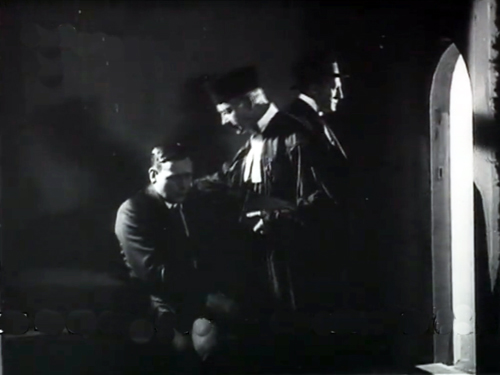

Tötet nicht mehr! displays some remarkable visual qualities. Cross-lighting in the climactic prison scenes sculpts Sebald, the priest, and the lawyer Landt in a bold variety of ways.

Director Lupu Pick (Sylvester, 1924) uses this dramatic lighting to enhance the tableau-plus-axial-cut approach. The police are examining the crime scene and questioning Sebald. A depth composition gives us the corpse in the lower foreground, the detectives in the middle ground, and way in the back, the barely-visible face of Sebald perched between the shoulders of the two central men.

One detective walks to the distant background to question Sebald. Anybody else would have staged this bit of action in the better-lit zone on the left, where a detective talks with his colleagues. Instead, far back, a single pencil-line of light picks out the edge of Sebald’s face and body.

An axial cut-in presents a tight two-shot of the cop and Sebald–again, made stark and tense by the lighting.

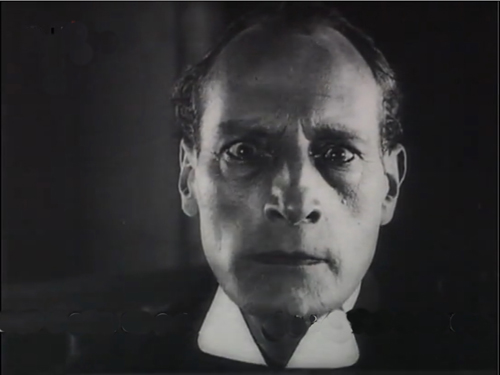

The plot of Tötet nicht mehr! is a generational one, starting with the tragedies befalling the woman’s father. These scenes introduce the sympathetic lawyer Landt, who tries to help the family throughout its troubles. Landt becomes the vehicle of the film’s message against capital punishment, which gets full airing in the boy’s trial.

In the films of the 1910s, courtroom scenes tend to be more heavily and freely edited than others. This is largely because of the need to cut among judges, jury, witnesses testifying, lawyers pontificating, and the onlookers. Pick exploits the situation with dozens of shots of participants. We also get optical point-of-view shots showing Sebald awaiting the jury’s verdict by staring at the doorknob of the jury room. There’s even a “lying flashback,” which dramatizes the prosecutor’s inaccurate reconstruction of the quarrel that led to the crime.

Most impressive, I think, is the pictorial progression in Landt’s impassioned plea to the jury to let Sebald escape execution. Among many reaction shots and reestablishing framings, Landt is rendered in increasingly close shots as he addresses the judges and the jury–and us.

The textural lighting and the ruthless elimination of the background reminded me of the trial scene of André Antoine’s Le Coupable of 1917, run at an earlier installment of Ritrovato.

There were plenty of other 1919 films on display, several of which I have yet to see. But this should give you an indication of the service that Cinema Ritrovato continues to render to the cause of understanding film history.

Not so long ago

The Widows of Noirmoutier (2006).

Film history close to our time was the subject of Varda par Agnès, the filmmaker’s last statement on her career. Prepared during her final years of life and produced by her daughter Rosalie Varda, it’s a poignant and revealing account of what mattered to her in her work. It showed Varda’s wry, playful humor and her commitment to treating social issues in intimate human terms. It’s a body of cinema that grows ever more important each year.

Varda par Agnès also showed her characteristic sensitivity to overall form. It’s framed by bits of her talking to audiences in master classes, so she becomes the narrator. Some stretches are chronological, going film by film, but just as often the links are associational. The women of Black Panthers (1968) remind her of the abortion activists of One Sings, the Other Doesn’t (1977). That’s about the friendship of two women, which suggests by contrast a film about a woman alone, Vagabond (1985). The beach of Vagabond summons up the plenitude of Le Bonheur (1965). And so on.

This might seem rambling, but it’s not. Varda explains that she often conceives her films with a strict structure–the strung-together tracking shots of Vagabond, the tight time frame and spatial coordinates of Cleo from 5 to 7 (1962). Varda par Agnès splits about halfway through, flashing back to Varda’s early still photography and adroitly linking that to her emergence as a “visual artist.”

She began mounting expositions like L’Îl et Elle, which housed cinema cabins (big transparent cubes made of ribbons of 35mm film) and Widows of Noirmoutier. Around a central image of collective grief, small screens show women sharing the everyday details of life without a partner. In just this clip, it’s almost unbearably touching. Apart from the resonance with Varda’s devotion to Jacques Demy, I was reminded of Chekhov’s line: “If you’re afraid of loneliness, don’t get married.”

We’ve been so busy with films, and queueing for films, that we’ve had little time to blog about our visit. Later entries will have to come after we’ve left Cinema Ritrovato.

Thanks as usual to the Cinema Ritrovato Directors: Cecilia Cenciarelli, Gian Luca Farinelli, Ehsan Khoshbakht, Marianne Lewinsky, and their colleagues. Special thanks to Guy Borlée, the Festival Coordinator.

The complete score for Song of the Scarlet Flower is available on CD and streaming.

For Varda’s last visit to Cinema Ritrovato, go here. We discuss Varda’s career and Kelley Conway’s in-depth study of it here. See also Kelley on Varda at Cannes. A forthcoming installment of our Criterion Channel series is devoted to Vagabond.

For more on the stylistics of 1910s films, see the category Tableau Staging. I discuss The President in the Danish Film Institute essay, “The Dreyer Generation.”

The Criterion Collection’s magnificent Bergman collection wins Best Boxed Set at the annual DVD awards, Cinema Ritrovato 2019. Congratulations to producer Abbey Lustgarten and all her colleagues!

Two essential German silent classics from Edition Filmmuseum

Der Gang in die Nacht (1921).

Kristin here:

Back in 2016, the Munich Film Archive gave us a preview of the restored version of F. W. Murnau’s earliest surviving film, Der Gang in die Nacht (1921). The print was splendid, and David posted an entry in which he analyzed the film’s style and situated it in the context of German cinema in the early post-World War I years. He tied the film to the tableau style that developed in much of the world outside the USA during the 1910s and which began to adjust to Hollywood norms of continuity editing just when Murnau was making films like Der Gang in die Nacht.

In that entry he used several frames from the restoration, and a glance over it will show its spectacular visual quality. I won’t spend much time on that film here, since David covered it so thoroughly. He wrote, “We can hope that the film will soon appear on DVD. Remember DVDs?” He and I certainly do. The Edition Filmmuseum obviously does as well. They continue to release their restorations and collections of more recent experimental films solely on DVD. Maybe Blu-rays are simply too expensive to produce, or perhaps the staff there consider Blu-rays a passing fad, like talkies. At any rate, this DVD release looks great (see above). it can easily be ordered from the Edition Filmmuseum’s shop (English page).

Apart from the tableau staging and the proto-continuity cut-ins that David discusses, there are some impressive depth shots–involving, as often happens in 1910s films, spectators in a theater box with the stage in the distance.

The film was restored from the original camera negative, though negatives were not edited in the final form of the film. By studying Murnau’s shooting script and restoration work previously done by Enno Patalas, the team were able to reconstruct the films’s editing and intertitles. The tinting and toning are based on the conventions of the period and are thoroughly plausible. David’s remarks in his earlier post are condensed slightly into this still applicable summary quoted in Stefan Drössler’s notes on the film:

The Munich Film Museum’s team has created one of the most beautiful editions of a silent film I’ve ever seen. You look at these shots and realize that most versions of silent films are deeply unfaithful to what early audiences saw. In those days, the camera negative was usually the printing negative, so what was recorded got onto the screen. The new Munich restoration allows you to see everything in the frame, with a marvelous translucence and density of detail. Forget High Frame Rate: This is hypnotic, immersive cinema.

The DVD lives up to that description.

A 1921 double feature

Without much fanfare, this release also contains another major classic of 1921, Scherben (“Shattered” or more literally “Fragments”). Its director, Lupu Pick, is probably best known today from his performance as the tragic Japanese spy, Dr. Masimoto, in Fritz Lang’s Spione (1928). He was, however, a prolific director from 1918 to 1931. (His acting career lasted from 1910 to 1928.) Many of his films are apparently lost, though I have seen two: Mr. Wu (1918) and Das Panzergewölbe (1924), both good but conventional films.

As a director, however, he is best known for making two of the main films in the brief vogue for Kammerspiele: Scherben and Sylvester, or New Year’s Eve (1923). These two films were scripted by Carl Mayer, who, as Anton Kaes points out in the accompanying booklet, wrote all the German Kammerspiele films: Hintertreppe (1921, dir. Leopold Jessner), Sylvester, and Der letzte Mann (1924, dir. Murnau). One might add Carl Theodor Dreyer’s Michael (1924), shot in Germany and scripted by Thea von Harbau.

Mayer was all in favor of films with no intertitles–though in practice that meant almost none. Der letzte Mann is one such, with an expository title introducing the sarcastic happy ending that Mayer was forced to add. Scherben is another. Near the end there is a single dialogue title. Moreover, Scherben’s subtitle is Ein deutsches Filmkammerspiel: Drama in fünf Tage. The five days are divided into the five reels of the film, and each is introduced by an expository title. There are a few letters and other texts that convey vital information, but overall the action is presented pictorially.

Scherben might be said to represent the slow cinema of its day. Its remarkable and lengthy opening shot is filmed from the front of a slowly moving train, simply showing progress along a track in a snowy landscape (above).

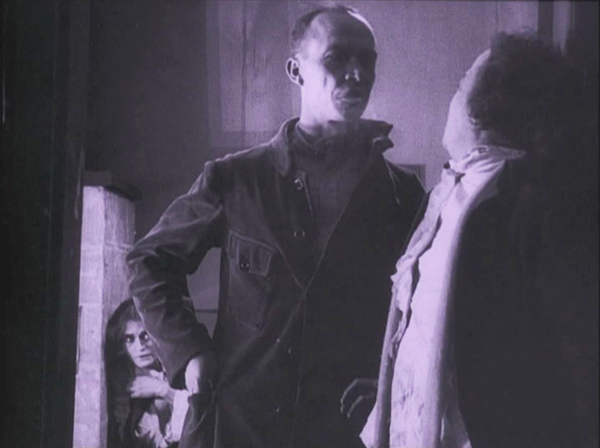

The main character (played by Werner Krauss, famous as Dr. Caligari) is a linesman, living with his wife and daughter in an isolated house. Their stultifying daily routine is gradually set up during the early scenes. Drama is introduced when a railroad inspector comes to visit, staying with the family. He and the daughter are immediately attracted to each other, spending a night together. The wife discovers this, staggers out into the snow to pray at a local shrine, and freezes to death. The tragedy deepens from there.

The film proceeds at the notoriously languid pace of German art films of the period. Pick injects stylistic flourishes derived from trends of the period. For some reason, the hallway of the family’s house has little Expressionistic painted highlights dotted around it.

Werner Krauss often acts “with his back,” well before Emil Jannings was praised for doing so in the framing prison scenes of E. A. Dupont’s Variety (1925.)

Pick calls upon the 1910s obsession with mirrors when the inspector reacts to accusations that he has seduced the linesman’s daughter.

Pick also evokes the depth staging of the tableau style, with small areas of the screen glimpsed in the background, most notably in the scene where the mother discovers the lovers together. (See below.)

The print is not as spectacular as that of Der Gang in die Nacht, having been reconstructed from prints in the Gosfilmofond archive in Moscow and the Bundesarchiv in Berlin without extensive digital restoration. Still, we should be glad to have this milestone film available. Taken together, the two films make a welcome addition to the number of German classics available for home viewing and classroom use.

Scherben (1921).