Archive for the 'Society for Cognitive Studies of the Moving Image' Category

Cinema in the world’s happiest place

Bust of Carl Theodor Dreyer in the Dagmar Bio, the film theatre he once managed.

DB here:

Denmark was the first foreign country I ever visited. Having never been to Canada or Mexico, I took off in the early summer of 1970. Technically, I touched down in Reykjavik first because I was flying Icelandic Airlines, the Ryanair of its day. You flew Icelandic to get to Europe as cheaply as possible. Although a few people got off at Reykjavik, most of us sat patiently on the tarmac before heading off to Copenhagen.

Ever since that summer, when blinding light invaded my basement room at 4:00 AM, I’ve had a soft spot for Denmark. Ib Monty, then head of the Danish Film Archive, kindly screened for me all the Dreyers I hadn’t seen, and in spare moments I learned the joys of Copenhagen’s canals and restaurants. Six years later I would spend nearly another whole summer there watching the same Dreyer films on a flatbed viewer in the archive vaults, a somewhat renovated army fort. Many visits later, including a couple to the charming city of Aarhus, I’m still a fan of the Danes. They manage to be modest yet accomplished, hard-working yet hard-partying. They put cultural figures like composer Carl Nielsen on their currency. We’re told that they are the happiest people in the world. I don’t doubt it.

So it was with special pleasure that I returned to Copenhagen for two weeks in June. The second week was consumed by a day of talks and seminars at the University of Copenhagen and then by the convention of the Society for Cognitive Studies of the Moving Image. I’ve given two long-winded previews of the latter event, and I hope to have more coverage of it in a later entry. Today, a smorgasbord of other things Danish–without, alas, mention of H. C. Andersen, Vilhelm Hammershøi, or Victor Borge.

Chaos reigns, more or less

The organizers of our SCSMI event pulled off a coup: Not only were we shown Antichrist in Asta, one of the Danish Film Institute‘s fine theatres, but along came Lars von Trier to spend an hour talking about it afterward.

The film struck me as mid-level von Trier, not as good as The Idiots, The Kingdom, Dancer in the Dark, and The Boss of It All (though others would call me out for admiring this last). It lacks the element of game-playing that I enjoy in what von Trier calls his “mathematical” works, most famously The Five Obstructions. Instead, Antichrist provides perhaps the most unadulterated surge of emotion and mystical/ mythical implication to be found in all his work. It tries to be an intellectual horror film somewhat in the David Lynch mode, with a plaintive, roiling soundtrack and unearthly visions, including a fox snarling, “Chaos reigns!”

I was surprised that the elements so sensationalized by the press are pretty brief; snip out four brief shots and you’d have a ferocious but much less controversial movie. It starts as your basic two-handed psychodrama, with a couple tearing at each other. As in those other duologues Strindberg’s The Stronger and Bergman’s Persona, the film presents a fluctuating power struggle–the man trying to rule through cool rationality, the woman tapping depths of grief and repressed anger.

Yet the film goes beyond psychodrama into realms of history and myth. The grieving mother rises into demonic fury by getting in touch with witchcraft, the subject of her unfinished university thesis. Antichrist could thus be read as an exercise in misogyny or as a celebration of woman’s primal energies. (For what it’s worth, several women in our audience said they liked the film a lot.) Of course the whole thing looks very fine, with a stylized black-and-white prologue (some shots taken at 1000 frames per second), and the rest rendered in that dodging, wandering camera style von Trier and the brilliant cinematographer Antony Dod Mantle have made their own.

The entire Q & A with von Trier, moderated by Peter Schepelern, is available as an audio file on the SCSMI conference website, perhaps to be followed by a video record. Some excerpts:

Von Trier explained that the film came out of a period of prolonged depression. “I used this project to get out of bed [every day].” Yet it’s less personal than his other works, he thinks, because it lacks his usual interest in rules, obstacles, and formal play–“a little more messy.” And he feels that by not operating the camera, he lost some intimacy with actors.

Von Trier explained that the film came out of a period of prolonged depression. “I used this project to get out of bed [every day].” Yet it’s less personal than his other works, he thinks, because it lacks his usual interest in rules, obstacles, and formal play–“a little more messy.” And he feels that by not operating the camera, he lost some intimacy with actors.

The Antichrist project seems to have brought out a mystical side of von Trier that hasn’t been so prominent in his public image. Years ago he conceived a film in which Satan created the earth, but that dissolved. Certain elements of the film, especially the emblematic forest creatures–blackbird, deer, and fox–come from his interest in shamanism. He has, he claims, traveled in alternative worlds with animal guides. “Never trust the first fox you meet.”

Is it a horror film? At least it has sources in the genre. Uncharacteristically, von Trier prepared for the project by revisiting not only classic horror films he admired, The Exorcist, The Shining, and Carrie, but also The Ring and Dark Water. He was particularly influenced in his youth by Altered States, another venture into “fantasy travels.”

He commented on how his free-camera technique imposed certain constraints in sound work. If you execute a “time cut”–that is, cutting directly to a new scene starting on a shot of a character–you must alter the sound somehow; otherwise the audience is likely to think that the action is continuous. This got me thinking about how The Boss of It All violated that convention, when each continuity cut actually yields a different sound ambience because each of the many cameras is miked separately.

Why is the film dedicated to Tarkovsky? “It was a way of getting rid of psychology.”

“I do not work with the audience in mind. I make films I would like to see myself.”

The Last is not least

Last Friday night the filmmaking program at the University of Copenhagen gave out its student film awards. The crowd was large and boisterous, the atmosphere festive and tipsy. I was honored to present the prize for the best fiction film, which went to desidst (punning on De sidst, “The Last”). The three winning filmmakers, pictured above, were Sissel Marie tonn-Petersen, Niels Holst-Jensen, and Toke Westmark Steensen.

Before I read the result, though, I was confronted with some damaging evidence in a copy of Film History: An Introduction.

Peaking in the 1910s

During my first week in Copenhagen, I was viewing Danish films from 1911 to 1915. As long-time readers of this blog know, I’m fascinated by the films of the 1910s, and Denmark boasts some of the most sophisticated works of the time. Thomas Christensen and Mikael Brae of the Danish Film Archive kindly let me watch several films, mostly from the once-mighty Nordisk film company.

The most remarkable films I saw were Ekspeditricen (1911), Dyrekøbt Aere (“Hard-Won Honor,” 1911), and Under Blinkfyrets Straaler (“Under the Beam of the Lighthouse,” 1913). All three of these offer sophisticated examples of the dominant storytelling technique of that period, what has been called the tableau style.

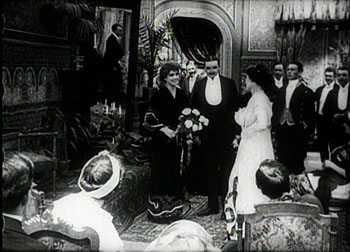

I can’t offer any visual analyses here, as I don’t have frame stills available in digital form, but here’s an example of the kind of thing I’m studying, taken from August Blom’s The Ballet Dancer (1911). Camilla (Asta Nielsen) has been seduced by Jean, a man-about-town, and she has come to sing for a society soirée at which Jean is present. But Jean is also carrying on an affair with the host’s wife.

The scene starts with the host Simon walking with his wife to the middle of the salon. Note the mirror in the upper area of the frame, just left of center.

She goes out frame right, and the host welcomes Camilla, bringing her to the central zone of the shot.

The hostess returns from off right to greet Camilla. Now we can see Camilla’s lover Jean in the mirror.

The hostess leaves the frame again, her husband settles into a chair, and Camilla starts to sing. But in the mirror we can see Jean bending over to kiss the hostess.

Soon Camilla notices Jean’s flirtation, and he straightens up.

Camilla interrupts her song, shouting and thrusting an accusing finger at the couple across the room.

I especially like the way in which Camilla’s finger points both at the offscreen couple and directly at her guilty lover’s reflection. If we haven’t noticed Jean’s infidelity yet, we certainly should now.

Today the same scene would be handled with lots of cutting and point-of-view framings, but the mirror allows Blom to pack a single long shot with simultaneous actions. (Mirrors were something of a signature device in Danish films of the period.) It’s a nice example of Charles Barr’s notion of gradation of emphasis, a principle that was at the heart of the intricate, sometimes exquisite ensemble staging we find so often in the 1910s.

Far from being a static, “theatrical” rendering of the action, the tableau technique looks forward to the deep-space stagings we associate with Welles and Wyler, as well as the distant long-take style of Theo Angelopoulos and Hou Hsiao-hsien. Studying film history is often our best way to understand the cinema of our moment, and perhaps of our future. At a more primal level, a week of prime examples of the tableau tradition gave me a fine dose of Danish happiness.

For background on the Society for Cognitive Studies of the Moving Image conference this year, try here and here. Earlier blog entries on this site have dealt with other aspects of 1910s cinema: director Yevgenii Bauer, tight staging in De Mille’s Kindling (1915), the emergence of classical film style around 1917, editing in William S. Hart movies, the years 1913 and 1918, and the triumph of Doug Fairbanks. I’ve proposed more complete accounts of 1910s staging strategies, and their impact on film history, in On the History of Film Style and Figures Traced in Light: On Cinematic Staging.

An excellent introduction to Danish cinema of this period is Ron Mottram’s 1988 Danish Cinema before Dreyer, a book which deserves to be reissued or put online. You can sample Danish 1910s films at the DFI archive database, where several clips are posted. Try these fragments: København ved nat (1910), Den frelsende Film (1916), and Kaerlighedsvalsen (1920). DVD versions of some 1910s classics, including The Ballet Dancer, can be ordered from the DFI Cinemateket shop; in the US, the titles are available for institutional purchase from Gartenberg Media. Everyone interested in silent cinema should own the Dreyer, Christensen, Psilander, and Asta Nielsen discs.

Who will watch the movie watchers?

DB here:

Today, I offer more on cognitive film studies, the activities of the Society for Cognitive Studies of the Moving Image, and why both matter. For background, visit the previous post and here and here. Throughout, I’ll harken back to the issue of convergent audience responses: How can viewers from different cultures grasp certain appeals that films provide?

This research tradition seeks to answer questions about moving-image media, especially questions of an artistic nature. The researchers examine filmmaking with the assistance of findings and theoretical frameworks that have emerged in the cognitive sciences of psychology, anthropology, and other disciplines. Some specifics:

Cognitive film studies emphasizes explanations over interpretations. Explanations can be causal (what made this happen) or functional (pointing out the purposes that something fulfills). When human action is part of what we’re studying, the explanations tend to involve goals and motives, means and ends. By contrast, a lot of humanistic media study emphasizes interpreting films but leaves causal and functional processes unexamined.

This research tradition is mentalistic. In explaining viewers’ responses, it looks first to features of the human mind. This doesn’t mean that researchers study minds cut off from society; rather, the emphasis is on the mental activities tied to all sorts of experience, including social action and interaction.

This tradition is naturalistic. The explanations it mounts try to fit in with current understanding of human capacities as analyzed by the social sciences. That entails that psychoanalysis, another mentalistic theory of human action, has not on the whole proven a source of reliable explanations. Some cognitively inclined researchers would add that psychoanalytic inquiry has been fruitful for pointing to areas of behavior that answer to naturalistic investigation.

The line of argument, accordingly, is that of rational inquiry, induction and deduction. It stands in contrast to much current film theory, which consists of more or less free association and the rote citation of major thinkers. Cognitive film theory tries to formulate clear-cut questions and to seek answers that have empirical grounding and conceptual coherence.

The tradition has a strong tendency to look for cross-cultural regularities among artworks and viewer experiences. The sources of these regularities need not be innate in any strong sense. Critics sometimes claim that cognitivists believe that everything is “hard-wired,” but virtually no cognitivists say or believe that. For one thing, our “wiring” changes at certain critical periods, especially two months, nine months, and four years of age. Moreover, the regularities in behavior we notice occurring across cultures or social milieus may have come into existence for many contingent reasons. That doesn’t make them any less interesting as explanatory factors.

For example, no culture is without fibers to bind things, but we shouldn’t expect to find a “string” gene or neuron. In this case, and many others, humans equipped with some common faculties and faced with common demands have found common solutions. We can study shared strategic behaviors without committing ourselves to biological determinism.

People who believe in the cultural construction of nearly everything appeal to learning as the means by which cultural processes shape individual action. Yet cultural constructivists have on the whole been unable to specify how learning is possible. Since an utterly vacant mind could never actively pursue or acquire or organize knowledge, we’re obliged to consider that some innate propensities are in place before humans make contact with the manifold of experience. No one needs to teach a newborn to pick out moving objects or synchronize lip movements with sound patterns.

Moreover, if you rest your case on the metaphor of construction, you need to specify the materials out of which action is built. Up to a point you can say that there are cultural constructions out of other constructions and so on. But the system has to get started somewhere. You have to be able to see color before you can learn that stoplights and stop signs are red. Ingrained capacities and tendencies are the best candidates for being the stuff out of which various cultural conventions are constructed.

Most cognitivists hold to the post-Chomskyan view of learning as the unfolding and refinement of innate predispositions and mental structures. In order to learn something, you need to know something else. In fact, a lot else. It now seems overwhelmingly evident that humans come into the world with many predispositions, some broad and vague, some quite concrete. Some of these are primed in the womb, as with a newborn’s preference for mother’s smell. Other predispositions require only a few confirming encounters to be locked in. A baby is sensitive to a certain range of phonological and prosodic patterns, and so she is ready to fasten on those characteristic of a specific language. Babies seem as well to have an intuitive physics; they are surprised when objects disappear or turn into something else. Babies also are sensitive to eye contact and smiling, both crucial to social interaction and reading others’ intentions.

In sum, the most plausible learning model is that of predispositions, often sometimes quite narrowly constrained, that are confirmed and fine-tuned by the environment (often within a critical period of exposure). We need active engagement with the environment, both physical and social, to let our intrinsic capacities develop to their full strength. Nature via nurture, as Matt Ridley likes to say.

One implication for film is that humans would be likely to recognize film images without extensive training or even a lot of exposure. (Sermin Ildirar found this in the village study mentioned in my previous post). Some understanding of the actions and emotions we see onscreen may have quite specific neural sources, with “mirror neurons” as currently good candidates for grounding recognition and empathy. Other patterns of storytelling and style could be quickly learned, as they piggyback on our understanding of real-world knowledge of social interactions.

Having a battery of predispositions would make sense in evolutionary terms. We gain survival advantage by coming into the world ready to have our biases fine-tuned by experience. Increasingly, for some researchers, the puzzles of cinematic convergence and divergence find their ultimate explanations in human biological and cultural evolution.

Booked

Noël Carroll and JJ Murphy, SCSMI convention June 2008.

I try never to take the present moment as a culmination or turning point in anything. Yet I can’t help noticing that the tenets of cognitive film studies chime in with three wider trends in our current intellectual life.

First, there is a burst of interest in the psychology of informal reasoning. A host of books talks about the shortcuts, heuristics, and predictable errors we make in everyday actions. Examples would be Carol Tavris and Elliot Aronson’s Mistakes Were Made, Ori and Rom Brafman’s Sway, Gary Marcus’s Kluge, Jonah Lehrer’s How We Decide, Joseph T. Hallinan’s Why We Make Mistakes, and Dan Zariely’s Predictably Irrational. The flourishing area of behavioral economics, typified by Akerlof and Shiller’s Animal Spirits, is an outgrowth of this line of inquiry. Most of these books explore the cognitive biases that were brought to light by psychologists some time ago, but now emotion is seen as playing a central role.

A second thread in the cultural conversation involves neurology. Now that brain scanning has yielded more precise ways of tracking mental activity, our common-sense actions are seen to have surprising and tangled roots. Many of the books just mentioned draw upon neuroscience to identify the sources of cognitive biases. A rich survey of the neurological territory as currently mapped can be found in Human: The Science Behind What Makes Us Unique, by Michael Gazzaniga.

Then there’s the hottest topic of all, a renewed interest in evolutionary biology. A host of books is rolling out explaining and debating Darwinism. (By the way, Charles, happy centenary.) A good recent example is Jerry Coyne’s Why Evolution Is True. But the interest in evolution has given a new salience to evolutionary psychology, that area of inquiry that investigates how our minds have been shaped and constrained by adaptation and other evolutionary processes.

Evolutionary psychology came to prominence in the social sciences with the 1992 breakthrough book The Adapted Mind: Evolutionary Psychology and the Generation of Culture. There Jerome H. Barkow, Leda Cosmides, and John Tooby flung down a challenge to traditional social science. Most researchers assumed that the mind was plastic and variable to a very large extent, both between cultures and within an individual’s lifetime. Culture held an irresistible sway over mental life. The essays collected in The Adapted Mind, particularly Tooby and Cosmides’ introductory manifesto, suggested that psychologists needed to consider evolution as a powerful source of explanations for mental activity. Steven Pinker’s The Blank Slate (2002) brought this line of thinking to a much broader public.

Although many humanists are proud of owing nothing to science, it’s curious that they often share traditional social sciences’ belief in a more or less blank slate. Virtually everything is culturally constructed; any biological givens are written off as nonexistent, unimportant, or uninteresting. But some humanistic scholars are starting to show that such factors possess both interest and explanatory value.

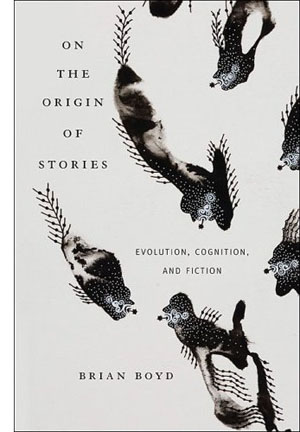

Studies linking art and literature to biological and cultural evolution are enjoying great prominence this year. Denis Dutton’s The Art Instinct and Brian Boyd’s On the Origins of Stories have sparked a wide discussion of how the play instinct, mate selection, and other adaptations might shed light on narrative, music, and the visual arts.

Now, when cognitive and evolutionary models are the latest thing in literary studies, to be applauded or denounced by the MLA rank and file, it’s worth remembering that film studies has been plowing this field for quite some time. Some people would say that my Narration in the Fiction Film (1985) opened up this wing of film studies, but although that book drew on current developments in cognitive psychology, it didn’t outline a broad research program.

More far-reaching was Noël Carroll’s “The Power of Movies,” also published in 1985. Carroll’s seminal essay laid out a concise explanation of cultural convergence through cinema, or as he put it, how “movies have engaged the widespread, intense response of untutored audiences throughout the century.” Carroll’s critique of then-current film theory, Mystifying Movies (1985 again), developed the essay’s idea as a counterweight to psychoanalytic and neo-Marxist explanations for the power of popular cinema. The importance of attention, the role of visual techniques in shaping uptake, and the possibility of evolutionary sources for cinema’s appeals—these and other themes of today’s cognitive film research can be found in Carroll’s work of twenty-five years ago. I suppose that “The Power of Movies” is the cognitivist’s equivalent to Mulvey’s “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema.”

A turning point?

Joe, Barb, and Amy Anderson; SCSMI convention, June 2008.

Grand Theory in the humanities has prided itself on being cutting edge, yet it has ignored virtually all of the major developments in the human sciences, from Chomskyan linguistics through cognitive science and now evolutionary and neurological research. That ignoral can seem almost wilful. The 1990s saw a flourishing of cognitive film theory, such as Ed Tan’s study of emotion in cinema and Murray Smith’s study of characterization. Yet in 2006, when I was invited to London to give a paper surveying the perspective, I seemed to be speaking Martian. Two of the most distinguished senior film scholars in the UK said they couldn’t really comment adequately. The approach was all so new and unfamiliar!

If I had been haughty enough to offer two veterans of Screen some reading tips, I could have referred them to two compelling overviews. Paul Messaris’s Visual Literacy: Image, Mind, and Reality (1994) synthesized psychological and anthropological research on how people responded to media and concluded that there wasn’t yet any evidence that images and their normal combination were radically coded. Joseph Anderson’s Reality of Illusion (1998) showed how key questions of cinematic perception and comprehension have been addressed by empirical research in the social sciences. Joe and his wife Barbara were also pioneers in bringing evolutionary explanations to bear on cinematic problems, thanks to James J. Gibson’s “ecological” frame of reference.

In just the last year, three of the people deeply involved with SCSMI have published books that push the conversation in fresh directions. Assume that widely distributed propensities, either innate or converging through cross-cultural regularities, get fine-tuned by the specifics of cultural experience. How do these convergences and divergences emerge in films?

The most wide-ranging book comes from Torben Grodal. His first book, Moving Pictures (1999), was part of the last decade’s surge of cognitivist work. In Embodied Visions: Evolution, Emotion, Culture, and Film (Oxford), Grodal continues to explain our experience of film with the help of what we know about how brain areas are activated. At the center is the process that Torben calls PECMA (for Perception-Emotion- Cognition-Motor-Action). In this model, activation begins in brain areas dedicated to perception and flows on to associational and emotional centers, and then to areas providing cognitive appraisal. Here Grodal agrees with current thinking on the central role of emotion in processing information. Along with this “inner” account of cinematic response, Torben proposes an evolutionary account of enduring cinematic attractions. Romantic love, horror, and adventurous exploration all have evolutionary rationales.

The most wide-ranging book comes from Torben Grodal. His first book, Moving Pictures (1999), was part of the last decade’s surge of cognitivist work. In Embodied Visions: Evolution, Emotion, Culture, and Film (Oxford), Grodal continues to explain our experience of film with the help of what we know about how brain areas are activated. At the center is the process that Torben calls PECMA (for Perception-Emotion- Cognition-Motor-Action). In this model, activation begins in brain areas dedicated to perception and flows on to associational and emotional centers, and then to areas providing cognitive appraisal. Here Grodal agrees with current thinking on the central role of emotion in processing information. Along with this “inner” account of cinematic response, Torben proposes an evolutionary account of enduring cinematic attractions. Romantic love, horror, and adventurous exploration all have evolutionary rationales.

On both fronts, the book tries to balance the convergence/ divergence tendencies. Take My Neighbor Totoro.

The film is clearly influenced by its Japanese origin, from the use of Shinto gods to the rice fields and sliding doors. But the fact that children all over the world are fascinated by the film is only loosely related to those cultural specificities. . . . Miyazaki uses a series of devices that tap into innate and universal mental mechanisms and emotions. Central, of course, is the fascination with the soft, organic counterintuitive agent Totoro, who provides attachment security and empowerment for the little girl, Mei, in the absence of the parents.

Torben goes on to discuss how Miyazaki exploits our interest in “counterintuitive” phenomena, like ghosts and gods, in the figure of a cat who is also a bus.

While Embodied Visions offers a very broad theoretical framework, Carl Plantinga’s Moving Viewers: American Film and the Spectator’s Experience (University of California Press) focuses on Hollywood cinema and how it arouses emotions. Plantinga, who also contributed to the 1990s discussions, surveys the literature on emotion and explores varieties of emotions in film viewing. He makes fruitful distinctions between “long-range” emotions, like suspense, and those brief and intense feelings, like surprise and disgust.

While Embodied Visions offers a very broad theoretical framework, Carl Plantinga’s Moving Viewers: American Film and the Spectator’s Experience (University of California Press) focuses on Hollywood cinema and how it arouses emotions. Plantinga, who also contributed to the 1990s discussions, surveys the literature on emotion and explores varieties of emotions in film viewing. He makes fruitful distinctions between “long-range” emotions, like suspense, and those brief and intense feelings, like surprise and disgust.

Perhaps more interesting, Carl suggests that while sympathetic narratives evoke compassion and pity, distanced narratives evoke cooler feelings, like respect or disdain. This distinction allows him to deny that the common claim that the aesthetic distance we find in Antonioni or Angelopoulos is unemotional; these artists simply deal in different emotions. The distinction also enables him to puncture the belief that Hollywood offers only sentimental hogwash.

It might be thought that sympathetic narratives are the norm in Hollywood. Yet distanced narrative is pervasive in Hollywood, as it is in the “art” cinema. The distanced mode rejects the evocation of strong sympathy for characters—sympathies that are sometimes dismissed as sentimentality—in favor of a more distanced, critical, sometimes humorous, and occasionally cynical perspective.

Plantinga’s examples are action films like The Hunt for Red October, which evokes admiration for gallant stoicism, ironic comedies like Raising Arizona, and puzzle films like House of Games and The Usual Suspects.

One of Carl’s key points is that sympathetic narratives must evoke some negative emotions, when their characters are hit by misfortune. So melodrama is the sympathetic narrative par excellence. Moving Viewers closes with a sensitive discussion of how a film can orchestrate negative emotions in complicated ways, focusing on disgust as it is evoked in films as different as Mask and Polyester.

A comparable concern for how culture can fine-tune cross-cultural tendencies is set forth by Patrick Colm Hogan in Understanding Indian Movies: Culture, Cognition, and Cinematic Imagination (University of Texas). Hogan is an expert on Indian literature and aesthetics; I called him in to help me understand Slumdog Millionaire in an earlier entry. Hogan is also a major narrative theorist. His The Mind and Its Stories is a powerful study of cross-cultural narrative structures and their relation to prototypical emotions.

A comparable concern for how culture can fine-tune cross-cultural tendencies is set forth by Patrick Colm Hogan in Understanding Indian Movies: Culture, Cognition, and Cinematic Imagination (University of Texas). Hogan is an expert on Indian literature and aesthetics; I called him in to help me understand Slumdog Millionaire in an earlier entry. Hogan is also a major narrative theorist. His The Mind and Its Stories is a powerful study of cross-cultural narrative structures and their relation to prototypical emotions.

Understanding Indian Movies shows how those universal plot structures gain richness and emotional force through their encounter with Indian traditions and current social conditions. For example, the sacrificial plot found in all cultures is particularized in Santosh Sivan’s The Terrorist. The film transforms the standard plot for the sake of ideological point and emotional force, modeling its suicide-bomber tale on the assassination of Rajiv Gandhi. “The contemporary history depicted by the film was already emplotted in a prototypical narrative form by the people who made that history.”

Hogan’s book is not as localized in its concerns as the title might imply. It’s not only about how to watch Indian movies but also about how to do cognitive studies of media. For instance, Patrick often pauses to criticize over-simplified evolutionary explanations, and he urges that such explanations be used cautiously. But he nonetheless defends the overall convergence/ divergence perspective.

On the one hand there is particularity—not merely the particularity of national cultures, but the particularity of regions, religions, castes, classes, philosophies, ages, and so forth, all the way down to individuals. On the other hand, there is the common genetic heritage of the human brain, the common principles of childhood development (beyond genetics), the recurring practices that arise from group dynamics—a whole series of universal principles that we all share. . . . Whether we are European, Chinese, African, or Indian, Christian, Jewish, Hindu, or Muslim, it is these universals that make it possible for us to understand Indian movies and to appreciate them, rather than merely drawing abstract inferences about them, as if they were part of some inscrutable puzzle.

The differences among these books are considerable. Grodal wants explanations at the level of neurology. Plantinga, of a philosophical temper, wants to clarify the concepts we use to talk about emotions in our experience of films. Hogan is constantly looking for the political implications of artistic choices. But such a range of emphasis matches the variety of the papers assembled for our next meeting.

The Society for Cognitive Studies of the Moving Image meets next week in Copenhagen. Patrick Hogan, alas, will not be joining us. But Torben Grodal is speaking on “Crime Fiction from a Biocultural Pespective,” and Carl Plantinga is giving a talk called “Models of Real and Hypothetical Spectators.” Once more, a complete list of papers can be downloaded here.

In sum, evidence is mounting that the SCSMI is now the gathering point for a very robust, accessible, and exhilarating approach to thinking about how films work and work upon us—all of us.

Research conducted by SCSMI members is available in The Journal of Moving Image Studies and in Projections.

Noël Carroll’s essay “The Power of Movies” can be found in his Theorizing the Moving Image (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996), 78-93. He revisited these ideas in the 1996 essay “Film, Attention, and Communication: A Naturalistic Perspective,” available in Engaging the Moving Image (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2003), 10-58. Some SCSMI members will be represented in the forthcoming Evolutionary Approaches to Literature and Film: A Reader in Science and Art (Columbia University Press), edited by Brian Boyd, Joseph Carroll, and Jon Gottschall. Evolutionary Psychology, by Robin Dunbar, Louise Barrett, and John Lycett provides an excellent survey of several of the ideas I gestured toward today.

Himmelskibet (The Space Ship, aka A Trip to Mars, 1918).

Invasion of the Brainiacs II

DB here:

What gives movies the power to arouse emotions in audiences? How is it that films can convey abstract meanings, or trigger visceral responses? How is it that viewers can follow even fairly complex stories on the screen?

General questions like this fall into the domain of film theory. It’s an area of inquiry that divides people. Some filmmakers consider it beside the point, or simply an intellectual game, or a destructive urge to dissect what is best left mysterious. Many readers consider it academic bluffing, another proof of Shaw’s aphorism that all professions are conspiracies against the laity.

These complaints aren’t quite fair. Early film theorists like Hugo Münsterberg, Rudolf Arnheim, André Bazin, and Lev Kuleshov wrote clearly and often gracefully. Even Sergei Eisenstein, probably the most obscure of the major pre-1960 theorists, can be read with comparative ease. Moreover, generations of filmmakers have been influenced by these theorists; indeed, some of these writers, like Kuleshov and Eisenstein, were filmmakers themselves.

But those day are gone, someone may say. Does contemporary film theory, bred in the hothouse of universities and fertilized by High Theory in the humanities, have any relevance to filmmakers and ordinary viewers? I think that at least one theoretical trend does, if readers are willing to follow an argument pitched beyond comments on this or that movie.

That is, film theory isn’t film criticism. Its major aim is more general and systematic. A theoretical book or essay tries to answer a question about the nature, functions, and uses of cinema—perhaps not all cinema, but at least a large stretch of it, say documentary or mainstream fiction or animation or a national film output. Particular films come into the argument as examples or bodies of evidence for more general points.

In about three weeks, about fifty people will gather at the University of Copenhagen to do some film theory together. It’s the annual meeting of the Society for Cognitive Studies of the Moving Image. I talked about the group last year (here and here) in the runup to our Madison event.

The sort of theorizing we’ll do, for all its variety, is in my view the most exciting and promising on the horizon just now. It’s also understandable by anyone interested in puzzles of cinematic expression, and it has powerful implications for creative media practice.

We’ll also be in Copenhagen for Midsummer Night, which is always pleasant. Go here for the lovely song that thousands of Danes will try to sing, despite terminal drunkenness. No real witches burned, however.

Concordance and convergence

But back to topic: Puzzles of cinematic expression, I said. What puzzles? Well, films are understood. Remarkably often, they achieve effects that their creators aimed for. Michael Moore gets his message across; Judd Apatow makes us laugh; a Hitchcock thriller keeps us in suspense. What enables movies to reliably achieve such regularity of response?

It’s not enough to say: Moore hammers home his points, Apatow creates funny situations, Hitchcock puts the woman in danger. Any useful explanation subsumes a single case to a more general law or tendency. So a worthwhile explanation for these cinematic experiences would appeal to more basic features of artworks, cultural activities, or our minds. We can pick up on Moore’s message because we know how to make inferences within certain contexts. We can laugh at a joke because we understand the tacit rules of humor. We recognize a suspenseful situation because… well, there are several suggestions.

This sort of question is largely overlooked by theorists of Cultural Studies, another area of contemporary media studies. They typically emphasize difference and divergence, highlighting the varying, even conflicting ways that audiences or critics interpret a film.

Studying how viewers appropriate a film differently is an important enterprise, but so is studying convergence. Arguably, studying convergence has priority, since the splits and variations often emerge against a background of common reactions. A libertarian can interpret Die Hard as a paean to individual initiative, while a neo-Marxist can interpret it as a skirmish in the class war, but both agree that John and Holly love each other, that her coworker is a weasel, and that in the end John McClane’s defeat of Hans Gruber counts as worthwhile. Both viewers may feel a surge of satisfaction when McClane, told by a terrorist he should have shot sooner, blasts the man and adds, “Thanks for the advice.” What enables two ideologically opposed viewers to agree on so much?

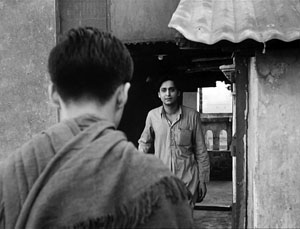

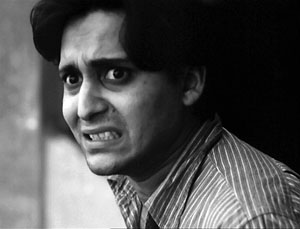

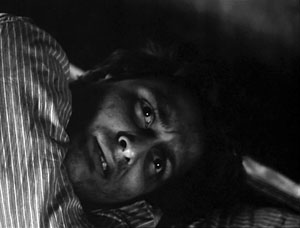

Films aren’t just understood in common; they arouse remarkably similar emotions across cultures. This is a truism, but it’s been too often sidestepped by post-1960 film theory. Who, watching The World of Apu, doesn’t feel sympathy and pity for the hero when he learns of the sudden death of his beloved wife? Perhaps we even register a measure of his despair in the face of this brutal turn of events.

We can follow a suite of emotions flitting across Apu’s face. I doubt that words are adequate to capture them.

Are these facial expressions signs that we read, like the instructions printed on a prescription bottle? Surely something deeper is involved in responding to them—for want of a better word, fellow-feeling. Indians’ marriage customs and attitudes toward death may be quite different from those of viewers in other countries, but that fact doesn’t suppress a burst of spontaneous sympathy toward the film’s hero. We are different, but we also share a lot.

The puzzle of convergence was put on the agenda quite explicitly by theorists of semiotics. Back in the 1960s, they argued that film consisted of more or less arbitrary signs and codes. Christian Metz, the most prominent semiotician, was partly concerned with how codes are “read” in concert by many viewers. Today, I suppose, most proponents of Cultural Studies subscribe to some version of the codes idea, but now the concept is used to emphasize incompatibilities. So many codes are in play, each one inflected by aspects of identity (gender, race, class, ethnicity, etc.), that commonality of response is rare or not worth examining.

A complete theoretical account, if we ever have one, would presumably have to reckon with both differences and regularities. The dynamic of convergence and divergence is a central part of one arena of film studies that has, for better or worse, been called cognitivism.

Sampling

Gathering for Uri Hasson‘s keynote lecture, SCSMI 2008.

The cognitive approach to media remains a pretty broad one, and the Society for Cognitive Studies of the Moving Image hosts a plurality of approaches at its annual meetings. SCSMI has become home to media aesthetes, empirical researchers, and philosophers in the analytic tradition who are interested in interrogating the concepts used by the other two groups. Last year’s gathering, at our campus here in Madison, created a lively dialogue among these interests.

For instance, some of us Film Studies geeks wonder why people so consistently ignore mismatched cuts. Dan Levin’s ingenious experiments on “change blindness” provide a hilarious rejoinder. In one study conducted with Dan Simons, a stooge asks directions of an innocent passerby. As they’re talking, a pair of bravos carry a plank between them, and another confederate is substituted for the first one.

You guessed it. Most subjects don’t notice that the person they’re talking to has changed into somebody else! So how can we worry about mismatched details in cuts? Actually, Dan’s research isn’t just deflationary. It helps spell out particular conditions under which change blindness can occur.

Another stimulating talk was offered by Jason Mittell. He asked how long-running prime-time TV serials can solve the problem of memory. In this week’s episode what strategies are available to recall the most relevant action of earlier episodes? How can previous action be presented without boring faithful fans? Jason, who has a new book on American TV and culture out this spring, went beyond describing the strategies. He suggested how they can become a new source of formal innovation, as in the Death of the Week in Six Feet Under.

Sermin Ildirar of Istanbul University presented the results of a study on adults living in a village in South Turkey. These viewers were older, ca. 50-75, and—here’s the interesting part—had never seen films or TV shows. To what extent would they understand “film grammar,” the conventions of continuity editing and point-of-view, that people with greater media experience grasp intuitively? To facilitate comprehension, the researchers made film clips featuring familiar surroundings.

The results were intriguingly mixed. Some techniques, such as shots that overlapped space, were understood as presenting coherent locales. But most viewers didn’t grasp shot/ reverse-shot combinations as a social exchange. They simply saw the person in each shot as an isolated figure.

The discussion, as you may expect, was lively, concerning the extent to which a story situation had been present, the need to cue a conversation, and the like. I found it a sharp, provocative piece of research. Stephan Schwan, who worked with Sermin and Markus Huff, has become a central figure studying how the basic conventions of cutting and framing might be built up on the basis of real-world knowledge, and both he and Sermin are back at SCSMI this year.

Stephan Schwan, Thomas Schick, Markus Huff, and Sermin Ildirar, with Johannes Riis in the background; SCSMI 2008.

There were plenty of other stimulating papers: Tim Smith’s usual enlightening work on points of attention within the frame, Johannes Riis on agency and characterization, Paisley Livingston on what can count as fictional in a film, Patrick Keating on implications for emotion of alternative theories of screenplay structure, Margarethe Bruun Vaage on fiction and empathy, and on and on.

One of the best things about this gathering was that the ideas were sharply defined and presented in vivid, concrete prose. I can’t imagine that ordinary film fans wouldn’t have found something to enjoy, and of course many of these matters lie at the heart of what filmmakers are trying to achieve. Indeed, some filmmakers regularly give papers at our conventions. The much-sought link between theory and practice is being made, again and again, in the arena of the SCSMI.

Last year I came to believe that this research program was hitting its stride. My hunch is confirmed by this year’s gathering in Copenhagen. The department of media studies there has long been a leader in this realm. You can download a Word version of the schedule here.

Lest you think that the conference participants don’t talk much about particular movies, I should add that there’s one film we’ll definitely be talking about this time around. Our Copenhagen hosts have arranged for a screening of von Trier’s Antichrist.

Next time: Going deeper into cognitivism, and three recent explorations.

Malcolm Turvey makes a point to Trevor Ponech and Richard Allen, SCSMI 2008.

Kristin and I have talked about pictorial universals elsewhere on this site. See her blog entry on eyeline matching in ancient Egyptian art, and my comments on “representational relativism” here.

Images at the top of this entry are taken from the Danish film Himmelskibet (The Space Ship, aka A Trip to Mars, 1918).

Books, an essential part of any stimulus plan

The Pathé Palace theatre, Brussels, designed by Paul Hamesse.

DB here:

Some shamefully brief notes on new publications. Disclaimer: All are by friends. Modified disclaimer: I have excellent taste in friends.

You call me reductive like that’s a bad thing

It’s easy to see why we might tell each other factual stories. We have an appetite for information, and knowing more stuff helps us cope with the social and natural world. We can also imagine why people tell fictitious stories that we think are true. Liars want to gain power by creating false beliefs in others. But now comes the puzzle. Why do we spend so much of our time telling one another stories that neither side believes?

Brian Boyd’s On the Origin of Stories: Evolution, Cognition, and Fiction (Harvard University Press) is the first comprehensive study of how the evolution of humans as a social, adaptively flexible species has shaped our propensity for fictional narrative. The book is a real blockbuster, making use of a huge range of findings in the social and biological sciences. Brian paints a plausible picture, I believe, of the sources of storytelling. Along the way he shows how two specimens of fiction, The Odyssey and Horton Hears a Who, exemplify the richness and value of make-believe stories.

Brian Boyd’s On the Origin of Stories: Evolution, Cognition, and Fiction (Harvard University Press) is the first comprehensive study of how the evolution of humans as a social, adaptively flexible species has shaped our propensity for fictional narrative. The book is a real blockbuster, making use of a huge range of findings in the social and biological sciences. Brian paints a plausible picture, I believe, of the sources of storytelling. Along the way he shows how two specimens of fiction, The Odyssey and Horton Hears a Who, exemplify the richness and value of make-believe stories.

The standard objection to an evolutionary approach to art is that it’s reductive. It supposedly robs an individual artwork of its unique flavor, or it boils art-making down to something it isn’t, something blindly biological. Art is supposed to be really, really special. We want it to be far removed from primate hierarchies, mating behavior, or gossip. For a typical criticism along these lines, see this review of Denis Dutton’s The Art Instinct. Brian has already adroitly responded to this sort of complaint here. See also Joseph Carroll’s examination of reductivism on his site.

It seems to me that all worthwhile explanations are reductive in some way. They simplify and idealize the phenomenon (usually known as “messy reality”) by highlighting certain causes and functions. This doesn’t make such explanations inherently wrong, since some questions can be plausibly answered in such terms. For example, often the literary theorist is asking questions about regularities, those patterns that emerge across a variety of texts. That question already indicates that the researcher isn’t trying to capture reality in all its cacophony. (For me, it’s all about the questions.)

Literary humanists sometimes talk as if they want explanations to be as complex as the thing being explained. But that would be like asking for the map to be as detailed as the territory. In fact, however, humanists tacitly recognize that explanations can’t capture every twitch and bump of the phenomenon. Consider some types of explanations that are common in the humanities: Culture made this happen. Race/ class/ gender / all the above caused that. Whatever the usefulness of these constructs, it’s hard to claim that they’re not “reductive”—that is to say, selective, idealized, and more abstract than the movie or novel being examined. Likewise, when people decry evolutionary aesthetics for its “universalist” impulse, I want to ask: Don’t many academics take culture or the social construction of gender to be universals?

I want to write more about Brian’s remarkable book when I talk about our annual convention of the Society for Cognitive Studies of the Moving Image. For now, I’ll just quote Steven Pinker’s praise for On the Origin of Stories: “This is an insightful, erudite, and thoroughly original work. Aside from illuminating the human love of fiction, it proves that consilience between the humanities and sciences can enrich both fields of knowledge.”

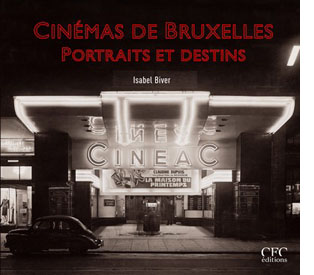

Faded beauties of Belgium

In its day, Brussels played host to some fabulous picture palaces. Now after years of research Isabel Biver has given us a deluxe book, Cinémas de Bruxelles: Portraits et destins. It’s the most comprehensive volume I know on any city’s cinemas.

Isabel glides backward from contemporary multiplexes and tiny repertory houses to the grandeur of the picture palaces. The Eldorado was a blend of Art Deco style and quasi-African motifs sculpted in stucco. King Albert graced the opening in 1933. There was the Variétés, a multi-purpose house built in 1937. It had rotating stages, air conditioning, and space for nearly 2000 souls (cut back to a thousand when Cinerama was installed). It was, Isabel claims, the first movie house in the world to be lit entirely by neon.

Isabel glides backward from contemporary multiplexes and tiny repertory houses to the grandeur of the picture palaces. The Eldorado was a blend of Art Deco style and quasi-African motifs sculpted in stucco. King Albert graced the opening in 1933. There was the Variétés, a multi-purpose house built in 1937. It had rotating stages, air conditioning, and space for nearly 2000 souls (cut back to a thousand when Cinerama was installed). It was, Isabel claims, the first movie house in the world to be lit entirely by neon.

Then there was the Pathé Palace, shown at the top of this entry. Dating back to 1913, it boasted 2500 places and included cafes and even a garden. This imposing Art Nouveau building was designed by Paul Hamesse, probably the city’s most inspired theatre architect. Hamesse also created the Agora Palace, which opened in 1922. Huge (nearly 3000 seats), the Agora was one of the most luxurious film theatres in Europe.

And we can’t forget the Métropole, the very incarnation of the modern style. Sinuous in its Art Deco lines, it packed in 3000 viewers. When it opened in 1932, it attracted nearly 53,000 spectators during its first week. The neon on the Métropole’s façade lit up the night, and its two-tiered glassed-in mezzanine became as much a spectacle as the films inside. See the still at the bottom of this earlier entry of mine. A ghost of its former self still sits on the Rue Neuve. Local historians consider the failure to preserve the Métropole a scandal in the city’s architectural history.

Cinémas de Bruxelles is a model presentation of local theatres. Not only does it trace the history of the major houses, but it includes a glossary of terms, a large bibliography, and an index of all theatres, both central and suburban. Needless to say, it is gorgeously illustrated. Whether or not you read French, I think you would enjoy this book, for it evokes an age we’re all nostalgic for, even if we didn’t live through it.

A TV interview with Isabel in French is here, with glimpses of what remains of the Métropole. She also gives guided tours of the remaining cinemas in the city center and in the neighborhoods. More information here.

A guy named Joe

Tropical Malady.

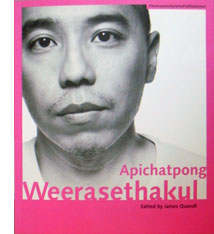

It’s seldom that a young filmmaker gets a hefty book devoted to him. Apichatpong Weerasethakul (aka Joe) will turn forty next year. He comes from Thailand, not a country adept at negotiating world film culture, and he is known chiefly for only four features. Yet he has become one of the most admired filmmakers on the festival circuit. His films are apparently very simple, usually built on parallel narratives. They have a relaxed tempo, exploiting long takes, often shot from a fixed vantage point, and scenes whose story points emerge very gradually. Joe’s movies tease your imagination while captivating your eyes. Each one could earn the title of his first feature: Mysterious Object at Noon.

It’s appropriate, then, that the tireless Austrian Film Museum has published a lavish collection of critical studies. Edited by James Quandt, the anthology arrives along with a massive retrospective of the director’s work, which includes many short documentaries and occasional pieces.

It’s appropriate, then, that the tireless Austrian Film Museum has published a lavish collection of critical studies. Edited by James Quandt, the anthology arrives along with a massive retrospective of the director’s work, which includes many short documentaries and occasional pieces.

James’ introductory essay, as evocative and eloquent as usual, is virtually a monograph, discussing all the features in depth. Alongside it are discerning essays by other old hands. Tony Rayns offers his usual incisive observations, focusing largely on Joe’s short films and the recurring imagery of hospitals, while Benedict Anderson surveys the Thai reception of Tropical Malady. Karen Newman offers precious information and judgments about Joe’s installations. The director himself signs several essays and participates in interviews and exchanges. Even Tilda Swinton has something to say.

I remember when Mysterious Object at Noon played the Brussels festival Cinédécouvertes in 2000. I was baffled. Joe’s movies taught me to watch them, and finally with Syndromes and a Century I got in sync. Its austere lyricism, off-center humor, and patiently unfolding echoes win me over every time I see it. (You can search this blogsite for several mentions, but JJ Murphy has a fuller appreciation of Syndromes here.) Thanks to Alexander Horwath and his colleagues for making this wonderful anthology, decked out with color stills and rich bibliography and filmography, available to us—and in English.

Zap goes the Chazen

Zap, Snarf, Subvert, Young Lust, Tits & Clits, Air Pirates Funnies, Slow Death Funnies, Feds ‘n’ Heads, Corn Fed Comics, Dope Comix, Cocaine Comix, Corporate Crime Comics: The names define the era. The sixties didn’t end until the mid-1970s, and these outrageous cartoon books really came into their own after the election of Nixon in 1968.

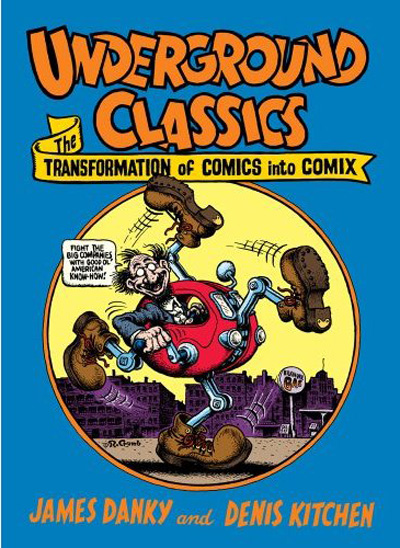

On 2 May, the Chazen Museum on our campus launches its exhibition, Underground Classics: The Transformation of Comics into Comix, 1963-1990. A whirlwind of events, including films and lectures, will revolve around galleries full of imagery from the demented pens of Kim Deitch, Aline Kominsky Crumb, Trina Robbins, Gilbert Shelton, Robert Crumb, Bill Griffith, and many other cartoonists.

The show was originated by Jim Danky, a scholar of public media from our State Historical Society, and Denis Kitchen, comic artist and the publisher of Kitchen Sink Press here in Wisconsin. Jim has long argued for the archival value of minority and subcultural publications. He started our Center for Print Culture and has been an advocate for gathering print materials by and for children, women, and ethnic minorities. He virtually created the area of “alternative library journalism”—collecting obscure publications from all zones of the political spectrum. I recall his satisfaction in telling me that he had managed to acquire a collection of The War Is Now!, the radical Catholic newsletter published by Hutton Gibson, father of Mel.

The show was originated by Jim Danky, a scholar of public media from our State Historical Society, and Denis Kitchen, comic artist and the publisher of Kitchen Sink Press here in Wisconsin. Jim has long argued for the archival value of minority and subcultural publications. He started our Center for Print Culture and has been an advocate for gathering print materials by and for children, women, and ethnic minorities. He virtually created the area of “alternative library journalism”—collecting obscure publications from all zones of the political spectrum. I recall his satisfaction in telling me that he had managed to acquire a collection of The War Is Now!, the radical Catholic newsletter published by Hutton Gibson, father of Mel.

For some years Jim has been telling me about his efforts to mount the comix show. It’s no small matter to collect this elusive material and then persuade a museum to show it. Not too many galleries feature talking penises, Jesus visiting a faculty party, or Mickey and Minnie robbed at gunpoint by a dope dealer. Maybe we forget, in the age of the Web and The Onion, just how scabrous these things looked forty years ago. Actually, they still look scabrous. They also look pretty funny, and they’re often well-drawn. As a historical codicil, the exhibition includes 1980s images from artists extending the tradition, such as Drew Friedman and Charles Burns.

The show runs until 12 July 2009. If you can’t get to town, there’s the splendid catalogue. It includes essays by Jim and Denis, Jay Lynch, Patrick Rosenkranz, Trina Robbins, and Paul Buhle. There are free screenings of Fritz the Cat and Crumb at our Cinematheque. And you can read an interview with Jim about the show here.

Remember our motto: Lotsa pictures, lotsa fun.

Up next: Days and nights at Ebertfest.

The Eldorado Cinema, Brussels, designed by Marcel Chabot.