Archive for the 'New media: Technology' Category

Classical cinema lives! New evidence for old norms

Hero.

Kristin here—

Note: This entry was written for Jim Emerson’s Contrarian Blog-a-Thon (III).

When David and I got into film studies in the late 1960s and early 1970s, an era of Hollywood’s history was drawing to a close. Many of the great directors who had defined the classical studio era from the period of World War I to the early age of television were at or approaching retirement. Andrew Sarris’s pivotal book, The American Cinema: Directors and Directions 1929-1968 (1968) came out just in time to elevate their reputations by dubbing them with the fashionable French term auteur.

John Ford and Howard Hawks made their last films in this period (7 Women, 1966, and Rio Lobo, 1970). Alfred Hitchcock, Otto Preminger, and Vincente Minnelli kept driecting into the 1970s, though few would say their late films stacked up to their earlier ones. (Preminger did manage to struggle back after a string of turkeys to make a very creditable final film, The Human Factor, in 1980.) Sam Fuller kept working through the 1980s, but he had to go to France to do it. Billy Wilder’s last film came out in 1981, though most of us wish he had stopped with The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes in 1970.

The decline of these greats coincided with the rise of the New Hollywood generation, whose directors, originally dubbed “the movie brats,” have become the grand old men of the current cinema. It also coincided with the early rumblings of the blockbuster (Jaws, 1975) and franchise (Star Wars, 1977) age that we know today. Definitely a shift took place in the 1970s, but to what?

Many film historians have claimed that the films that have come out of Hollywood since roughly the end of the 1980s are radically different from those of the classical “Golden Age.” Factors like television, videogames, spectacular special effects, moviegoers with short attention spans, the internet, the acquisition of the old studios by multi-national corporations, and the resulting rise of franchises have all putatively given rise to a “post-classical” cinema. This phenomenon is sometimes also referred to as the “post-Hollywood” or “post-modern” era.

I’m suspicious of the “post” terms, vague as they are. Usually stylistic labels describe what something is, not what it follows. Do we speak of “post-silent” or “post black-and-white” cinema?

Post-classical films supposedly jettison the old norms of style and storytelling. Frenetic editing, constant camera movement, product placement, juggled time-schemes—these and other tropes of recent cinema have replaced the continuity system, the carefully structured screenplay, and the character-based storytelling of the classical era. Computer-generated imagery has enabled filmmakers to create action scenes, spectacular settings, and fantastical creatures that hold our attention so thoroughly that the plot ceases to matter.

Or not. David and I have spent much of our professional careers studying the norms of classical filmmaking. We’ve swum against the stream by claiming that, despite many changes in style and technique, the fundamental norms of classical storytelling have remained intact. The classical cinema is with us still, precisely because it enables filmmakers to present us with absorbing plots and characters. It also is a flexible filmmaking approach that can absorb new technologies and new influences from other media and bend them to its own uses.

It’s less seductive to proclaim a long-term stability in Hollywood than to trumpet revolutionary, transformational, epochal changes. Still, some things just work so well that people want to keep them going as is. American films have dominated world screens since 1915. Why tinker with an approach that works so well?

It’s amazing to think of it now, but back in the late 1970s, virtually no one had studied the traditional norms of Hollywood filmmaking. We all knew what the distinctive traits of the great auteurs were, but distinctive as opposed to what? Academics kept saying that someone should figure out just what the cinema of the classical studio era consisted of. What principles guided filmmakers? What assumptions did they share? Not realizing how much material was available on Hollywood cinema, we and our colleague Janet Staiger set out to document the norms of style, technology, and mode of production that composed the “classical Hollywood cinema.”

The result was a much larger tome than we had expected, The Classical Hollywood Cinema: Film Style and Mode of Production to 1960 (1985). After finishing it, David and I dusted off our hands, figuring that we had dealt with that topic. We went back to studying non-classical directors like Ozu, Eisenstein, Tati, Godard, Bresson, and Hou, confident that we had the knowledge to show exactly how and why their work differed from standard filmmaking.

Then claims about post-classical filmmaking started to appear. In our book, we had limited our survey to pre-1960 cinema because the breakdown of the studio structure and the competition from television led to a different situation in Hollywood. We did not, however, say that classical filmmaking died then. Quite the contrary; we said that it had endured through those changes in the industry.

Those favoring the post-classical explanation obviously disagreed with that. Bypassing our claims for the endurance of classical filmmaking, they borrowed our cut-off date of 1960, as if we had intended that year to signal the end of all aspects of the classical cinema—style, storytelling, mode of production, technology, the whole thing.

During the 1990s it became apparent that claims about post-classical cinema were becoming one very common way of dealing with modern Hollywood films. We decided to move well beyond 1960 and show that classical norms still prevail in American mainstream cinema. I wrote Storytelling in the New Hollywood (1999), which analyzes ten successful films of the 1980s and 1990s to show that they use narrative principles that are virtually the same as those that were standard in the 1930s and 1940s. Goal-oriented characters, dangling causes, appointments, double plot-lines, carefully timed turning points, redundancy—all these classical devices are still very much with us. The claim was not that every single film coming out of Hollywood adhered to classical norms, only that the vast majority did.

David went on to make a similar argument in The Way Hollywood Tells It (2006), though he deals with visual style as well as narrative. There he examines some of the new norms of storytelling, showing how they are variants of the older classical system. He discusses, for example, “intensified continuity,” where tighter framings on actors, faster cutting, and prowling camera movements have modified but not replaced the standard continuity approach to presenting a conversation scene.

One of the most persistent claims by proponents of a post-classical era is the spectacle made possible by CGI. With the thrilling fight sequences of The Matrix, the vast battles of The Lord of the Rings, the extensive recreation of historical places of Gladiator, and the fantastical creatures and places of The Chronicles of Narnia: The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, the individual scene supposedly becomes more spellbinding than the story in which it is embedded.

David and I have tried to refute this claim to some extent. I talk about Terminator 2 in the first chapter of Storytelling, showing that it has a tightly constructed, character-based narrative. David has a chapter section called “A Certain Amount of Plot: Tentpoles, Locomotives, Blockbusters, Megapictures, and the Action Movie,” where he examines films like Judge Dredd and The Rock. He demonstrates that they, too, have plots that adhere to traditional Hollywood norms. He puts forth a more detailed analysis in this online essay.

We’ve never really dealt much, however, with the issue of how CGI may or may not have elevated spectacle over narrative interest. Luckily now a new book does that and does it very well. Shilo T. McClean, in her Digital Storytelling: The Narrative Power of Visual Effects in Film (MIT Press, 2007), agrees with much of what we have claimed about the survival of classical filmmaking (though The Way Hollywood Tells It came out too late for her to have seen it). She builds upon our case by examining systematically and imaginatively the question of whether digital special effects support narrative interest. McClean convincingly demonstrates that DVFx (digital visual effects), as she terms them, are used in an enormous variety of ways, and most of these help to tell classically constructed stories.

We’ve never really dealt much, however, with the issue of how CGI may or may not have elevated spectacle over narrative interest. Luckily now a new book does that and does it very well. Shilo T. McClean, in her Digital Storytelling: The Narrative Power of Visual Effects in Film (MIT Press, 2007), agrees with much of what we have claimed about the survival of classical filmmaking (though The Way Hollywood Tells It came out too late for her to have seen it). She builds upon our case by examining systematically and imaginatively the question of whether digital special effects support narrative interest. McClean convincingly demonstrates that DVFx (digital visual effects), as she terms them, are used in an enormous variety of ways, and most of these help to tell classically constructed stories.

McClean’s basic points are two. First, DVFx are not used just in the more obvious ways, for big action scenes or elaborate fantasy and science fiction settings. They are applied for a wide range of purposes, from dustbusting (removing dust and other minor flaws from frames) to spectacular scenes. Far from being inevitably spectacular, DVFx are often invisible. (1)

Second, McClean claims that whether modest or spectacular, DVFx usually serve the narrative in some way—and she points out that practitioners in the industry invariably make that same claim.

Digital Storytelling started out as McClean’s dissertation at the University of Technology Sydney. It betrays its origins in a survey of the literature that takes up the first two chapters. There the author is somewhat too conciliatory, for my taste anyway, to a number of theorists’ claims about the breakdown of narrative in the digital-effects age. She tries to find something useful in each writer’s position, even though some of those positions are irreconcilable with the general standpoint she adopts.

Chapter 3 sketches the history of computer graphics and how they came to be used in films. McClean points out that DVFx are perfectly suited to the three criteria for the adoption of new technology that David and Janet formulated in their sections of The Classical Hollywood Cinema: greater efficiency, product differentiation, and support for achieving standards of quality. Like sound and color, DVFx have marked a major technological shift for the film industry, but like them, DVFx have been readily integrated into the existing division of labor. A modern digital studio, as she says, functions in much the same way as a physical one does. Indeed, in watching the credits of a modern film, we see lighting, matte paintings, and so on listed as the specialties for the digital craftspeople.

In these early chapters, McClean points out that in many ways DVFx simply replaces the traditional special effects of the pre-digital age. Most of Citizen Kane’s many effects are not supposed to be noticeable, and indeed for years historians were unaware of just how many it contained. In cases where DVFx create a flashy effect, as in the virtual camera movements through walls in Panic Room, the function is to inform the viewer of the locations of various characters and create suspense. Probably the most vital lesson one could take away from this book is that techniques can serve multiple purposes in a film. Spectacularity, as McClean calls it, and storytelling can co-exist in the same digital images.

The author also explains that, unlike what many writers say about DVFx, they are not simply a post-production technique used to ramp up the visual appeal of a film. Computer imagery is used from the pre-production stages onward, and the mise-en-scene and camera movements must be planned around them.

After this setup, the author systematically explores the factors that might influence the storytelling—or merely spectacular—use of DVFx. As we did in The Classical Hollywood Cinema, McClean samples a large number of films, 500 including shorts. Any film using DVFx, however unobtrusively, qualified.

On this basis, the author has distinguished eight types of DVFx usage. Documentary is one, as in films where computer reconstructions of ancient buildings are shown. Such usage comes into films when information is presented as part of the mise-en-scene, as with the educational film that is screened in Jurassic Park. The second type of DVFx usage, Invisible, is fairly self-explanatory. We are not supposed to notice when buildings are extended, clouds are added to skies, or smudges on actors’ faces disappear.

Seamless DVFx are those we know must be faked, even though the results look photorealistic. The recreation of ancient cities, as with Rome in Gladiator or giant storms, as in Master and Commander, are of this type. Exaggerated effects involves actions or things posited to be real but created in a stylized fashion. McClean cites the comic effects in Steven Chow comedies, and puts wire-erasure for stunts into this category. I assume The Hudsucker Proxy would be another instance.

Fantastical DVXs obviously involve impossible beings like dragons, cave trolls, and a wide variety of X-Men. McClean also finds them in non-fantasy, non-sci fic films like Forrest Gump, Big Fish, and Hero. Surrealist uses of effects can include mental representations, as in Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind and American Beauty, or a bizarre but objective world, as in Amélie.

Finally, there are New Traditionalist uses of DVFx, exemplified by Pixar’s films, and HypeRealist ones, like Final Fantasy.

Armed with this typology, McClean studies various approaches to film studies, testing what each one reveals about the use of DVFx. Since classical Hollywood cinema is based on character traits and goals, she begins by showing convincingly how DVFx can “establish, realize, and enhance” character. For example, films often use effects to put the protagonist in greater danger than would be safe to do in reality. The staged fights in Gladiator, the author argues, create a greater emotional engagement with the main character and make plausible the heroism that allows him to defeat his enemy in the end.

Next McClean tests how DVFx can change the impact of a film by analyzing a pre-digital film and its remake in the computer age. (As a method, this is similar to what David does in The Way Hollywood Tells It when he examines framing, editing, and other techniques in the two versions of The Thomas Crown Affair.) The case study chosen is the 1963 Robert Wise version of The Haunting and the Jan De Bont remake (1999). McClean presents considerable evidence that the inferiority of the later film has nothing to do with its expensive DVFx supernatural effects. Instead, she locates the problem partly in the removal of all the creepy ambiguity of the earlier version. De Bont also changes the heroine from a guilt-ridden, virtually suicidal woman (too wimpy in this politically-correct age?) to a strong, determined savior. The result is a conventional super-woman versus evil monster film where the digital effects stand out simply because the original story was stripped of its most intriguing elements.

McClean moves on to genre, an important subject given the apparent concentration of DVFx (the ones we notice, that is) in fantasy and sci-fi films. She rightly points out, “For all the many assertions that special effects are an emerging narrative form, no one has proposed the narrative structure that this new form demonstrates.” The author makes up for that lack herself, concocting an outline of a film based around a string of effects-laden action scenes. Her outline fits the descriptions of films as given by proponents of post-classicism. The result, however, doesn’t resemble any film I’ve ever seen.

In the genre chapter McClean uses an obvious research resource, but one that the post-classicists largely ignore. She has gone through the entire run of the special-effects journal Cinefex, on the assumption that the films it covers are those assumed to be most significant in terms of their DVFx. McClean lists the 291 films by genre, showing that sci-fi films and horror do not have a monopoly on DVFx. For example, thirty-three period and dramatic movies feature in her list.

To gauge the impact of the rise of franchises in modern Hollywood, McClean surveys the four Alien films, which begin in the pre-digital and move into the digital era. As with remakes, the author demonstrates through analysis that the decline in the series after its two first films had to do with a thematic shift and a change in the character of Ripley.

McClean does not overlook the auteur theory, tracing the work of Steven Spielberg during that same transition from pre-digital to digital cinema. Unlike the other effects-oriented giants of Hollywood, George Lucas and James Cameron, Spielberg has worked in many genres. As soon as DVFx became available, he used them in nearly all the ways listed in McClean’s typology, from the Invisible creation of the swooping airplanes in Empire of the Sun to the Exaggerated in the Flesh Fair setting in A.I. to the Fantastical Martians in War of the Worlds. Always in the service of the narrative.

Along the way McClean offers a number of astute observations. One of these is a novel argument against the “DVFx equals non-narrative spectacle” position. She points out that “In many instances technically weak DVFx will be forgiven if they are narratively congruent; it is the strength of the narrative that will carry them, rather than the other way round.” This claim is plausible when we consider how in the pre-digital age we tried to overlook the obvious back-projections and matte-work in Hitchcock films like The Birds and Marnie.

She also suggests some plausible reasons why bad films might be heavy with DVFx. In some cases the effects create a publicity hook that makes up for the lack of other production values. In others, an inexperienced director, carried away with the “cool” possibilities of DVFx, uses them to excess.

And finally someone has come out strongly against the use of the term “cinema of attractions” to describe modern films. Historian Tom Gunning originally coined this phrase in describing very early cinema, where magic acts with stop-motion disappearances and elaborately hand-colored dances were as common as narrative films. For that period, the label worked and was useful. Applying it to later eras just because films have spectacular sequences has rendered the term much less meaningful.

One thing that I particularly like about McClean’s book is that she shows respect for the films she discusses. She actually seems to enjoy both watching and writing about them. McClean asks questions of aesthetic import, and she treats films as artworks—some good, some bad, but all to be taken seriously as evidence for her case.

Her final chapter provides an excellent conclusion: “While DVFx have completely reequipped the storyteller’s toolbox, they have not rewritten the storyteller’s rulebook entirely.” Yes, classical cinema lives, and Digital Storytelling provides vital new evidence to bolster that claim.

(1) In Film Art, we have touched on this range in the section “From Monsters to the Mundane: Computer-Generated Imagery in The Lord of the Rings” (pp.249-251 in the 7th edition, pp. 179-181 in the 8th). McLean treats the topic in far more depth.

Virtually true, or maybe not

From DB, for once a brief blog:

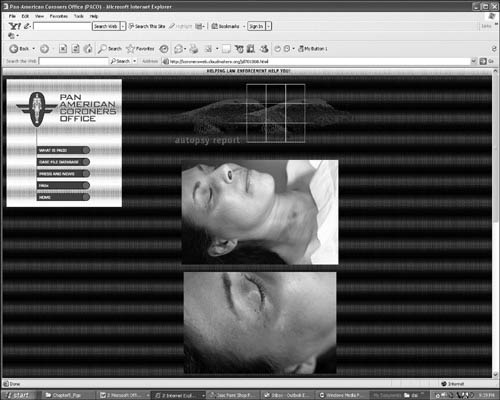

Perhaps the most enduring legacy of The Blair Witch Project was the idea of promoting the film through a faux website that treated the lore around the Witch as genuine. Later, the promotion for Spielberg’s A.I. created an alternate reality game (ARG) by scattering clues to a murder among many websites. The murder wasn’t part of A.I.‘s plot, but it did take place in the film’s fictional world, and online participants pursued an elaborate para-narrative that connected obliquely to the movie. A key character in the ARG, researcher Jeanine Salla, was listed as an actor in the film’s final credits. Ms. Salla evidently died a grisly death herself, as the autopsy report above indicates. She led other lives in fanfiction and online comic strips.

Now, for The Great World of Sound, director Craig Zobel has created a website. Nothing new in that. But Zobel also provides a website for a fictional company in the film. Here’s Screen International’s take (19-25 January 2007, print ed., p. 36):

It’s the 21st century equivalent of the film within the film—the fictional website of the shark-like record company in the movie. It’s everything you’d expect from a shady music company—flashing primary colors, bad clip art, typos and scrolling fonts, all to the sound of a soul-killing MIDI song file.

It starts well (banner reading, “You’re ad here”) but I found it not as wild as the SI description implies. Still, the idea is good, the execution diverting. Visit it here.

In a parallel thrust from Bookland, Jacquelyn Mitchard’s forthcoming young adult novel Now You See Her is being promoted by a series of YouTube video diaries purportedly made by the heroine, Hope Shay. The first one is up, and already at least one viewer thinks it’s the McCoy. (1)

We can probably expect to see more extensions of fictional worlds to the webworld. Are Hannibal Lecter podcasts next? Or an online university for which reading Special Topics in Calamity Physics is a prerequisite? See Henry Jenkins’ fine Convergence Culture for more on the A. I. puzzle ARG (pp. 123-128) and reflections on cross-media storytelling in general.

(1) Full disclosure: Hope is played by Lauren Peterson, the daughter of old friends Sue Collins and Jim Peterson. They also live down the street from us. Jim, now an attorney, took a Ph. D. in film studies here at UW. He’s the author of Dreams of Chaos, Visions of Order, an outstanding study of American avant-garde film.

PS Monday morning: I don’t watch much TV; The Simpsons, Olbermann, Ebert & Roeper, and the movie channels are pretty much it. So I’m grateful to Olli Sulopuisto for telling me that Lost has created its own ARG, The Lost Experience and that there’s a website for the fictional Hanso corporation. Much, much more can be found on the fansite.

My name is David and I’m a frame-counter

DB here:

Elsewhere on this site and in Figures Traced in Light (Chapter 1) and The Way Hollywood Tells It (second essay), I sometimes say rude things about the rapid editing in today’s films. But I’m actually a fan of fast cutting–when it’s precise, functional, and thoughtful. Most directors today don’t think about their cuts. Godard: “The only great problem of cinema seems to be more and more, with each film, when and why to start a shot and when and why to end it.”

My interest in fast cutting goes back to the 1960s, when I was first reading Eisenstein and seeing fims by Godard, Truffaut, Hitchcock, and, yes, Richard Lester. At first I would wind sequences backward and forward on a 16mm projector, stopping to pull the film off the reels to hold up to the light. For my dissertation on French cinema of the 1920s, I had a chance to examine films by Abel Gance, Jean Epstein, Germaine Dulac, et cie on editing tables or rewinds. In quickly-cut passages, the patterns of shot-length showed how a director could control the visual pace.

Over the years, when I studied 35mm film prints regularly, I periodically returned to my love of rhythmically cut passages. I studied Dreyer’s Passion de Jeanne d’Arc, the work of the Soviet Montage directors, and Asian action movies, from 1920s Japanese swordplay items to 1990s Hong Kong martial-arts sagas. Somewhat surprisingly, I found that Ozu, as in everything else, was there too; a lot of his intermediate spaces (landscapes, objects in rooms) are cut arithmetically.

By examining 16mm and 35mm prints, I could measure shot lengths in frames. In a sound film, a 24-frame shot would last a second on the screen. Things were trickier in gauging the cutting of silent films, since they were shown at rates between 16 and 24 frames per second. But at least the number of frames per shot gave me a sense of rhythmic relationships. A sequence in Jean Epstein’s Chute de la Maison Usher (1928) displays an arithmetical unfolding that would yield a distinct tempo at any projection speed of the era.

Directors have been counting frames for a long time. Experimental filmmakers like Brakhage did. Ozu had a special stopwatch built to register feet and frames during filming. Hitchcock cared about frame counting too. In Film Art‘s chapter on editing (pp. 224-225 of the new edition), we show how the gas station fire in The Birds gains impact from its steadily shorter shot lengths. The first shot lasts 20 frames, the second 18, the third 16, and so on down to 8 frames.

In sum, frame counting is one valuable way to find how a director can govern the pace of our pickup. When shots come this fast, our involvement can quicken as well.

When 35mm plays us false

For silent films, counting frames can be a problem if you have a “stretch-printed” copy. Since silent films often ran at something less than 24 frames per second (sound speed), some later film versions have been printed to repeat frames at certain intervals, to stretch out the print to 24 fps. That makes it easier to add a synchronized score to the print.

In the 1970s the Soviets were big fans of this procedure, rereleasing many classics by Eisenstein, Pudovkin, and others in stretch-printed 35mm and 16mm copies. The Soviet Montage filmmakers definitely counted frames, calculating the shots to play off each other rhythmically, so adding extra frames spoiled things. Worse, the stretch-printed versions often played sluggishly at sound speed, making the action spasmodic and blurring the figures. The result completely wrecked the rhythmic effects the directors were after. Even today, stretch-printed copies of Eisenstein’s Strike are in circulation.

Videotape and the 3:2 pulldown

Videotape arrived. The first Betavision players measured something–a little tally counter clicked away–but you couldn’t be sure what was being counted. Then came digital displays that measured hours, minutes, and seconds. But what about frames? When I tried to count frames on videotape, I found that the figures didn’t match those I got from film frames.

To see why, we have to remember that television developed its own frame rates. The technical details can get pretty daunting; see here for one account. I also recommend Jim Taylor’s DVD Demystified and Kallenberger and Cvjetnicanin’s Film into Video. Still, we non-engineers can get a general sense of what’s at stake.

There are two primary television standards, NTSC and PAL. NTSC (for National Television System Committee) is used primarily in North America and Japan. PAL (Phase Alternating Line) is common throughout Europe and Asia. Because NTSC video operates at a 60-Hertz refresh rate, the rate for individual frames is close to 30 per second. (Actually, it’s 29.97 fps.) The problem is this: Do you run 24-frame movies at 30 frames per second on television? This would make them look speeded up. Or do you pad out a second of film to fit a second of TV? American engineers took the second solution and created the so-called 3:2 pulldown.

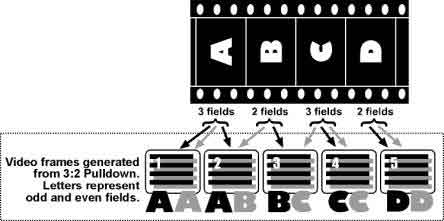

In interlaced video, each “frame” is really two venetian-blind image fields presented as one image on your screen.(1) In the 3:2 pulldown, some film frames are selectively repeated to fill out the video playback format. The film is converted to video by making two fields from one film frame and then three from the next frame. Here is a useful diagram from a site on video transfer.

The 3:2 pulldown preserves three of the original four film frames (video frames AA, CC, and DD above).

But you don’t see this exactly this result when you jog/shuttle through a videotape frame by frame because the VCR has been engineered to display the 3:2 pulldown slightly differently. Stepping through a videotape, we find that some frames will show phases of movement and some repeat a phase. Depending on your playback machine and the tape itself, you may get varying patterns. Usually I see four video freeze-frames decomposing a movement, then they’re followed by an extra frame in which nothing changes.(2) That process turns 4 film frames into 5 display frames. Adding 6 repeated frames to the original 24 frames yields 30 video frames a second. I find that you can get a rough sense of the number of frames in the original shot by ignoring the repeated frames in the video display, but the video frames showing decomposed movement may or may not correspond to the actual film frames.

Laserdiscs and the frame count

Those heavy, rainbow-flashing 12″ discs: Cinephiles loved ’em. They gave us a sharper picture, properly letterboxed, along with terrific sound. Aficionados today still prefer the rich digital sound of laserdiscs to the compression of many DVDs.

Most laserdiscs used the CLV (Constant Linear Velocity) format, which preserved and even exaggerated the effects of the 3:2 pulldown. Counting frames meant stepping through the stills and ignoring the repeated ones, as with videotape, but often the coupled frames (AB and BC above) shivered wildly. But in the high-end CAV (Constant Angular Velocity) format, laserdiscs were able to make each stored frame pristine. This is why people thought that laserdiscs would be used archivally, for storing paintings, photographs, manuscript pages.

A bonus of the CAV format was that in transferring motion pictures to disc, one film frame could be matched to a single video frame. In fact, each film frame was assigned its own number, so the counter display spit out digits with blinding speed. During normal playback, the 3:2 repeated frames were added in, but in STEP mode, CAV laserdiscs gave you the original film frames one by one–steady, crisp, and bright. Frame-counting gained a new piece of hardware.

DVD and frame counting

Laserdiscs used optical analog technology for the image track. But consumers wanted something easier to handle, on the model of the music CD, so in came digital image technology via MPEG-2 and the DVD.

Despite all the differences between digital video and film (color, resolution, artifacts, etc.), DVDs in the NTSC format gained one advantage over tape. Like CAV laserdiscs, they could preserve the 24-frames-per-second rate of film. Essentially MPEG-2 technology encodes the film frame by frame. Flags on the DVD instruct the player to regenerate extra frames during playback. For a more detailed explanation, go to Dan Ramer’s article here.

The result is that during freeze-frame viewing, a DVD can yield the original film frames. Watch the Universal DVD of The Birds, and the frame-counts correspond to the 20-18-etc. layout we discovered on a 16mm print. Your remote’s STEP button moves through the original frames, hiding the repeated ones that were shown during normal playback.

But not always. DVDs can sometimes play us false.

Before the DVD was a gleam in Warren Lieberfarb‘s eye, I studied King Hu’s wonderful A Touch of Zen on an editing table. There is a lot of frame arithmetic in the editing. During one swordfight, the mysterious stranger leaps away from the blows of Miss Yang and lands in a medium shot. He steps back, tipping up his face to reveal that she’s bloodied his head. He stares in astonishment. The shot lasts only 20 frames.

Yang stands still, holding her sword at the ready. The shot lasts a mere 9 frames, which dynamizes her stillness.

The stranger turns and runs out of frame in another twenty-frame shot. The static shot of Miss Yang now becomes an abrupt punctuation, and the stranger’s panic registers on us more sharply by being caught up in a repetitive rhythmic pattern.

Yang plunges after him, in a twelve-frame shot.

All four shots add up to less than three seconds of screen time, but they’re completely legible. It seems to me that the shots accentuate a pause in the fight by inserting a striking micro-rhythm, and then they dissolve that by letting the fighters continue the combat. Would that today’s filmmakers thought out their cuts so precisely! (If you want to learn more about King Hu’s editing style, see my Planet Hong Kong and the essay on him in the forthcoming Poetics of Cinema.)

But if you examine these shots on the US DVD of A Touch of Zen, you’ll find that the number of frames is way off from the film. The first and third shots run 25 frames each, not 20 frames; the second shot runs 11 frames (instead of 9), and the fourth 15 (instead of 12). Why? Inspection reveals our old friend, the 3:2 pulldown, at work. Improper authoring has left in the frames that should be jettisoned in step playback.

An even more severe instance: The sequence from Epstein’s Fall of the House of Usher that I admired in my dissertation days. It has become hash on the US DVD. When I try to count frames, I find that apparently the silent original has been stretch-printed and subjected to the 3:2 pulldown. When I click through the frames on a DVD player, I find that many frames are repeated, and some shots have doubled in length.

The lesson: Not all DVDs are created equal, or equally accurate in their correspondence with the original film.

What about PAL?

NTSC interlaced video has a 60-Hertz refresh rate. But PAL has a 50-Hertz one. That means not 30 video frames per second but 25. What do you do in transferring a film? The obvious answer: You speed it up.

Films shot at 24 frames per second tend to run at 25 in PAL videos, both tapes and DVDs. As a result, many films on European video run shorter than they did in the theatre, or on American DVDs. For example, Preminger’s Where the Sidewalk Ends runs 94:41 on the Fox DVD, but the same film, known as Mark Dixon Detective, runs 90:49 on the French DVD release. That’s a difference of nearly four minutes. PAL video playback of a 24 fps movie runs about 4% shorter than the original. For this reason, some European films are shot at 25 frames per second, to facilitate transfer to PAL.

So counting frames on a PAL videotape or DVD won’t necessarily mislead you on the number of frames, since none is repeated. That’s the case with our Touch of Zen example. Both the UK and the French DVDs of King Hu’s film yield the correct frame-counts for the shots in question. We just need to remember that each frame is onscreen for a tiny bit less time. In other words, each shot will contain the right number of frames, but that shot will be briefer in screen duration .

Note to Sátántangó fans: Yes, that means a much shorter movie. The PAL DVD available from England’s Artificial Eye claims to run 419 minutes; if you disregard opening and closing credits, the film runs a shade under 400 minutes. But the 35mm version I clocked here runs 434 minutes sans credits. So if you want to add 34 minutes to your life, watch the import DVD.

Note to Asian cinema fans: For reasons I don’t understand, many Hong Kong DVDs yield very blurred and vibrating still-frame images, not corresponding to the frames of the original film. These discs may be using a downmarket authoring process, or there may be problems converting to and fro between PAL and NTSC.

Progressive scan

This all applies to interlaced video, the original television broadcast format. Now we have progressive-scan video, for plasma and LCD displays and computer monitors. A progressive display, still adhering to the 60-Herz standard, is rigged to preserve the right number of film frames without repeating any.

But it does so by in effect combining two film frames together, and the step function may skip over several frames, or create a blurred composite that isn’t there on any frame. This is especially apparent on media-player computer software.

When I run my Touch of Zen shots on my computer, I get wildly abbreviated frame-counts in Step mode. In WinDVD, for instance, the first shot of the UK DVD registers as 8 frames, not 20; the second as 3 frames, not 9; the third as 9 frames, not 20; and the fourth as 6, not 12. Same thing for Epstein’s Fall of the House of Usher. On a tabletop DVD player there are more frames than in the original film; on my player’s software, there are fewer.

For this reason, I’d avoid trying to count frames on a computer’s media player.

So…..

Frame-counting is a nifty tool for discovering some secrets of filmmaking, but when we work from a video copy, we need to keep in mind the constraints of the various formats. And whenever possible, check the film!

(1) To complicate things, the scanning of alternate raster lines never yields a single complete frame. Before the image is fully completed at the bottom, it’s being refreshed at the top! To this extent, the video frame doesn’t have the stable, singular identity of a film frame. It can be encoded to correspond to a film frame, but as an image display, even a frozen frame is always in the process of being filled in. It’s just that our eyes, not designed to track such small-scale processes, are fooled.

(2) A quick sampling of my old VHS tapes shows that occasionally a tape doesn’t exhibit effects of the 3:2 pulldown. My Facets VHS copy of Where Is the Friend’s Home? plays back on two machines without any repeated frames. Perhaps this comes from making the transfer from a PAL master tape?

Film educators no longer criminals

Kristin here—

The rise of digital media has made the unauthorized copying of intellectual property easy. That, of course, drives the producers of that material crazy. We all know that the entertainment industry is said to be losing billions of dollars world wide from various sorts of piracy, from the sale of bootleg DVDs in southeast Asia to the downloading of sounds and images from the internet.

Much of this activity is undoubtedly illegal and undoubtedly violates entertainment producers’ copyright. But in trying to stem the tide of piracy, the industry hasn’t just gone after the wrongdoers. It has encouraged Congress to make more and more uses of intellectual property illegal, in the process riding roughshod over the Fair Use provision in the United States Code. A brilliant way to stamp out crime: make more activities into crimes and hence have more criminals to pursue. You’d think they have enough problems just going after the real pirates. But people like educators and scholars who try to use clips from movies in their classes or frame enlargements as illustrations in articles and books were thrown into the general mix of copyright violators.

That happened in 1998, when the Digital Millennium Copyright Act was signed into law by Bill Clinton. It essentially made any copying of visual or sonic material that involved breaking a digital encryption code illegal. All sorts of means exist to break these codes. Programs exist to grab frames from movies on DVD. Fans can post images on their websites (thereby offering the studios free publicity). Professors can import frames into their Powerpoint-based lectures. Scholars can illustrate their articles and books with reasonably high-quality images. The devising of such programs and the activities just mentioned were all illegal under the DMCA.

(For the Copyright Office’s own summary of the act, go here; for the Wikipedia summary, here.)

In the 1970s, when David and I were setting out to write Film Art and our other early books, we faced a similar issue, though at that time the copyright law concerning the use of frame enlargements was far less clear. Film studies was still a young field. Most publications on cinema, whether textbook or scholarly article, used studio-generated publicity photos as illustrations. We reasoned that such images did not reflect what really appeared in the film, since they were still photos taken on the set, often with different poses, lighting, and camera position. They were useless for the sort of close analysis we wanted to do.

Film Art thus became the first introductory film text to use frame enlargements extensively. Our publishers accepted the idea that such illustrations fell under fair use. Other publishers, however, were nervous about the idea. Did reproducing frames violate copyright? Editors weren’t always willing to risk finding out the hard way. Some authors paid large “permissions” fees to reproduce frames. Others gave up and settled for production stills.

Around 1990 I was asked by the Society for Cinema Studies (now the Society for Film and Media Studies) to chair a committee to investigate the validity of Fair Use as applied to film images. The result was the “Report of the Ad Hoc Committee of the Society For Cinema Studies, ’Fair Usage Publication of Film Stills’” (1993). This report established that fair use most probably applied to film frames, and educators and scholars were not violating copyright when they used slides or illustrations photographed from the original film. Several presses changed their policies as a result of the report, no longer requiring their authors to obtain unnecessary permissions for frame reproductions. The use of frame enlargements in scholarly publications spread, and film studies benefited as more authentic and useful images were employed by scholars.

Happy ending, right? Certainly the studios never sued over frame enlargements, before or after the report. In fact, relatively few authors were using frame enlargements. It took special equipment to photograph such frames: expensive camera attachments, color-balanced light sources, and the expertise to use both. Those of us publishing extensively illustrated books on Ozu or Eisenstein weren’t exactly a concern to the film industry. In fact, studio executives probably didn’t know that we existed and wouldn’t care if they had.

Then along came DVDs, which made frame grabbing easy. Scholars who had never bothered to get the special equipment or learn how to photograph film frames suddenly could quickly pull images for use in their publications. The reliance on publicity stills declined further. Frames were everywhere, all presumably covered by the same Fair Use law that 1993 report had opined applied to the reproduction of film frames. Legitimate users of frames had to get around the encryption codes, but like millions of DVD users around the world, most of them were savvy enough to do so.

I’m sure that the DMCA was not envisioned as applying to film scholars seizing frames for their publications or professors using visual examples in classes. Still, the provisions of the act were so broad that suddenly scholars and educators were criminalized for doing what they needed to do to foster knowledge: show clips from DVDs in lectures and use frame enlargements from DVDs in books and articles. They had to get around the studios’ codes that prevented piracy. Many of us went ahead and broke the codes and published DVD-derived illustrations in our books or compiled discs containing clips from films to show in lectures. The studios didn’t seem to care, since to the best of my knowledge no teacher or scholar had ever been prosecuted for violating the DMCA.

Finally the recognition of this ludicrous state of affairs has been partially remedied. The Librarian of Congress, James Billington, himself a fine scholar in the area of Russian and Soviet studies, recommended a series of exemptions to the DMCA. The first one relates to film: “Audiovisual works included in the educational library of a college or university’s film or media studies department, when circumvention is accomplished for the purpose of making compilations of portions of those works for educational use in the classroom by media studies or film professors.” (“Circumvention” is described as “circumvention of technical measures that control access to copyrighted works.”)

This is specific to classroom situations and only applies to DVDs owned by an educational institution. What if the teacher copies clips from his/her own DVDs to use in class? (All too frequent, given the tight budgets of universities and high schools.) Nevertheless, the general implication of this exemption is that the same Fair Use principle that applied to film clips and frames duplicated from analogue copies of films (i.e., 35mm and 16mm prints) should apply even if the educator or scholar is breaking a code to do that duplication. If clips are OK, why wouldn’t single frames be?

The exemption is a small step in chipping away at the monolithic laws protecting intellectual property that the studios are determined to put in place even when it goes against their own interests. Lectures, articles, and books do not damage the studios’ ability to exploit their own films commercially (one of requirements for Fair Use to apply). Quite the contrary. Film professors show clips and still images that publicize films and possibly inspire students to rent or buy DVDs. Articles and books similarly publicize films, even though their contribution to the attention paid to any given title is minuscule.

Making an exception in the DMCA as originally passed to allow for the educational/scholarly use of digital film images would never have occurred to the studios as they lobbied for this sweeping legislation. Few movers and shakers within the industry know there is such a thing as film scholarship, much less understand what we do. Fortunately people like Billington understand. His recommended exemptions went into force November 27.

So, film educator, the next time you prepare a lecture involving clips, you don’t need to pull the curtains, lock the doors, and glance nervously over your shoulder as you copy a tracking shot from Grand Illusion and another from The Magnificent Ambersons. You are no longer a thief.