Archive for the 'Film comments' Category

Ritrovato 2017: Many faces, many places

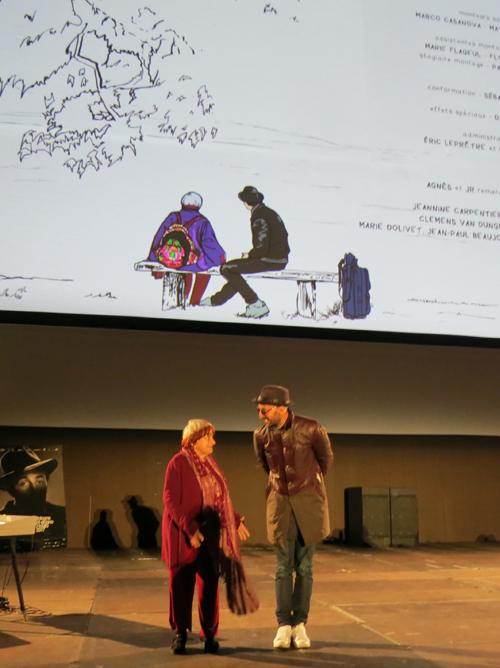

Agnès Varda and JR, Il Cinema Ritrovato, 1 July. Photo: DB.

DB here:

This final post from Il Cinema Ritrovato is no less a miscellany than the others. With over 500 films screened, Kristin and I invariably missed things that others raved about. Still, we saw enough powerful cinema to make us want to flag some key items for you.

Silents, please

Kristin has already mentioned one of the most startling items we saw, Le Coupable (1917) by André Antoine. I’m still processing the audacity of this film. The prosecutor in a murder trial abruptly claims the defendant as his son. We then get the familiar flashback format, shifting from the courtroom to the events leading up to the crime and the arrest. But the shifts between present and past are so quick, and the bits we see of the trial are given in such intense, stark singles, that they gain an astonishingly modern pulse.

Add in marvelous use of locations, real alleys and corridors and cafes, and you have a very impressive movie.

Once more, 1917 proves to be dynamite.

From the same year came Furcht (Fear), by Robert Wiene. Count Grevin wanders anxiously through his castle for about sixteen minutes of screen time before we realize, thanks to a flashback, that he’s haunted by his theft of a precious Indian statue, stolen from a temple. Soon a priest materializes, either on the castle grounds or in Grevin’s imagination, to declare that he has only seven years to enjoy life before vengeance strikes. Which it does, of course. Conrad Veidt plays the priest with the smoldering glare, and ambitious superimpositions show how committed German cinema was to special effects. Dr. Caligari was three years off.

Not that other years should be slighted. Le Collier de la danseuse (The Dancer’s Necklace, 1912) was an agreeably preposterous crime movie. (The thief has a jacket with fake hands dangling from the sleeves, just the thing for escaping handcuffs.) The film boasted the low, almost Ozuesque, camera height typical of other Pathé productions of the year.

Not that other years should be slighted. Le Collier de la danseuse (The Dancer’s Necklace, 1912) was an agreeably preposterous crime movie. (The thief has a jacket with fake hands dangling from the sleeves, just the thing for escaping handcuffs.) The film boasted the low, almost Ozuesque, camera height typical of other Pathé productions of the year.

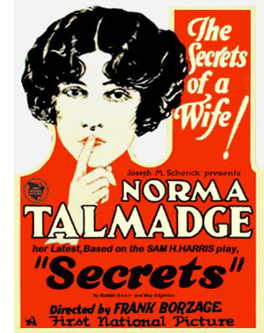

Borzage’s Secrets (1924) traces a marriage through three large flashbacks, with the first emphasizing romantic comedy, the second suspense, and the third family melodrama. Norma Talmadge, who savored a split-personality role in De Luxe Annie (1918), gets to play a woman at three ages here. The central section, devoted to a Griffithian siege on a lonely frontier cabin, showed Borzage’s ability to whip up enormous excitement, with an unexpectedly sad twist. The whole movie has over 11oo shots, indicating just how committed American filmmakers had become to fine-grained scene breakdowns.

All in all, the silent films on display this year were as revelatory as ever.

Cinematic geometries

The Abe Clan (1938).

For some years Ritrovato has included a Japanese sidebar curated by Alexander Jacoby and Johan Nordström. This year the theme was socially critical jidai-geki, or historical films. Some of them were fairly familiar to Western cinephiles because copies were circulated by the Japan Film Library Council from the 1970s onward. Examples include The Abe Clan (1938) and Fallen Blossoms (1938), both very good films. Along with these, the Bologna series gave the Yamanaka Sadao classic Humanity and Paper Balloons (1937) another well-deserved airing.

Some of these are fairly intimate dramas, others use a lot of spectacle. The image from Abe Clan above is fairly typical of the monumental turn some jidai-geki took in the late 1930s. Several of the films starred members of the left-wing Zenshinza kabuki troupe, perhaps best known to aficionados from Mizoguchi’s staggering Genroku Chushingura (1941-1942).

Three of the other films showed the range of this genre during Japan’s “dark valley,” its turn to authoritarian rule and imperial warfare. The Rise of Bandits (1937), by Takizawa Eisuke, was a rousing but melancholy Robin Hood tale. A lord’s honest son tries to save a shipment of gold from marauders, but he’s framed by his duplicitous brother. So he becomes the outlaws’ leader, at the cost of his wife’s life and his father’s trust. Some superb action sequences, including a fiery final assault on the castle, alternate with semicomic scenes among the bandits, with the hero’s cynical sidekick twisting not-too-bright thugs around his finger.

Hagiwara Ryo’s The Night Before (1939, production still above) was based on a Yamanaka script, and like Humanity and Paper Balloons, it braids together several characters’ fates. As rival samurai factions struggle during the Meiji restoration, ordinary people–an artist, a family running an inn, a young man wanting to make his name as a warrior, a bitter and disenchanted samurai–try to get by. One of the innkeeper’s daughters is attracted to the youth, another daughter who works as a geisha eyes the artist, and the old man seems to escape into endless games of shogi with a neighbor. The film has a panic-stricken climax, in which the factions collide in darkness along the riverside and innocents get swept up in the violence. As with many films in the series, the critique of mindless militarism isn’t far below the surface.

The Man Who Disappeared Yesterday (1941), by the great Masahiro Makino, is a murder mystery. An unpleasant landlord is the victim, and there are plenty of suspects. The scattered clues didn’t seem to me to play entirely fair, but the investigation is largely a pretext to explore adjacent households and obfuscate what turns out to be complicated post-murder maneuvers. At the climax, all the suspects are seated in a single line to hear the magistrate’s solution, just as if they were in Nero Wolfe’s office.

Makino’s style accentuates the spatial layout through a remarkable ten zoom-ins that yank us to one or another suspect as the explanation is given, sometimes with flashbacks. Camera zooms (as opposed to optical-printer ones, as in Citizen Kane) are rare in any national cinema of this period, and Makino uses them almost in the spirit of Hong Sangsoo, more to perk up our attention than to enlarge anything for closer scrutiny. (Admittedly, the last one rivets us on the guilty party.) The same geometrical impulse encloses the tale: an opening crane shot down, a closing one upward. As often in Japanese cinema, The Man Who Disappeared Yesterday marks and repeats film techniques to give a decorative flourish to the story.

Technique also comes to the fore, of course, in Divine (1935), a French production directed by Max Ophüls. The attraction isn’t just the dizzying camera movements, swimming through a tangle of backstage paraphernalia and crawling up stairways. Max is more than a master of the tracking shot. In one witty passage, framing and cutting coordinate to stretch the distance between a couple who can’t tear themselves away from each other. (In my last frame, the milkman’s head slides almost out of frame.)

The plot centers on a country girl who becomes a follies performer and is framed as a drug dealer by a Lothario and a lesbian. This contraption seems more or less a pretext for Ophüls to indulge his endless fascination with women striking poses for men while asserting their own demands. The abrupt and unexplained happy ending is the logical wrapup for a film less concerned with a plausible plot than a display of Woman in all her dazzling divinity. There. How’s that for a Sarris sentence?

Bigger than life

Although there were some repeats on Sunday, the final big event of the festival was the screening, to some 3000 people on the Piazza Maggiore, of the new film by Agnès Varda and JR. Kelley Conway reviewed its Cannes premiere for us earlier, and now that we’ve seen it, we like it a lot.

Varda has the ability to take a whimsical, borderline-cutesy idea and turn it into something poignant, as in Daguerreotypes and Opéra-mouffe. (Nursery-rhyming titles, like Mur Murs and Sans toit ni loi, encapsulate her attitude.) Her latest, an associational documentary along the lines of The Gleaners and I, depends on the premise of traveling through France and making enormous photographic portraits of ordinary people. These are then mounted on buildings in their home town–hence the title Visages Villages.

The result is both intimate and monumental. A postal clerk or a woman truck driver take on the billboard proportions of politicians and pop stars. Without any sense of slumming, Varda and JR can memorialize a woman living in a building about to be demolished, and can spare time for a haggard hermit who has dropped out of the system. It’s as powerful a populism as any you’ll see, but done with humor, genuine curiosity, and respect for the integrity of each subject. A playful approach to art can yield serious emotional effect.

As Visages Villages goes on, it turns introspective. Varda recalls episodes from her life and tries to incorporate one of her photos, a casual shot of Guy Bourdin, into a skewed tipsy WWII bunker rusting on a beach. She recalls young days with Godard and Karina, so that now when Godard dodges a meeting, she becomes rueful (“The rat!”). This lady gleaner is always gathering fragments, and we’re lucky she shares them with us.

Again Bologna gave excellent, overwhelming value. The surprises never stopped. Dropping into a film I hadn’t seen in three decades, Rancho Notorious, I not only had fun but realized once more Lang’s diabolical genius. A peculiar insert of a boot slipped into a stirrup puzzled me, but after an hour I got it. (Forgive me, Fritzie, for I knew not what I did.) Long may this festival flourish.

Thanks as ever to the vast and dedicated staff of Il Cinema Ritrovato, particularly Guy Borlée, Gian Luca Farinelli, and Mariann Lewinsky.

I discuss the trend toward monumental jidai-geki in chapters 12 and 15 of Poetics of Cinema. More detailed analysis can be found in Darrell William Davis’s book Picturing Japaneseness: Monumental Style, National Identity, Japanese Cinema.

Visages Villages (aka Faces, Places) is distributed by the Cohen Media Group.

Agnés Varda and JR. Photo: DB.

Ritrovato 2017: An embarrassment of riches

Place de la Concorde (somewhere between 1888 and 1904)

KT here:

David’s recent entry stressed the world-wide scope of offerings here at Il Cinema Ritrovato. The time period covered is even broader–this year as broad as it could possibly be. The final night’s film in the Piazza Maggiorre will be Agnès Varda and JR’s prize-winning documentary straight from this year’s Cannes festival, Visages Villages, with Varda here to introduce it. Yesterday we saw a work that may have been created before the cinema itself had been properly invented.

The earliest years

Somewhere in the time period 1888 to 1904, French scientist Etiennes-Jules Marey created a huge photographic format, a filmstrip 88 mm wide and 31 mm high. He exposed a series of images along this broad strip but never intended to project them as a film. As with much of Marey’s work, these high-quality photographs were tools to allow him to analyze movements, in this case those of humans and horses in the Place de la Concorde.

The National Technical Museum in Prague has scanned this series of frames to create a digital copy that can be projected in motion. The results, lasting only 45 seconds, has a clarity and detail that seems to rival that of Imax film. (The image at the top only hints at the effect.) We watched the piece four times and would have been glad to see it at least as many more.

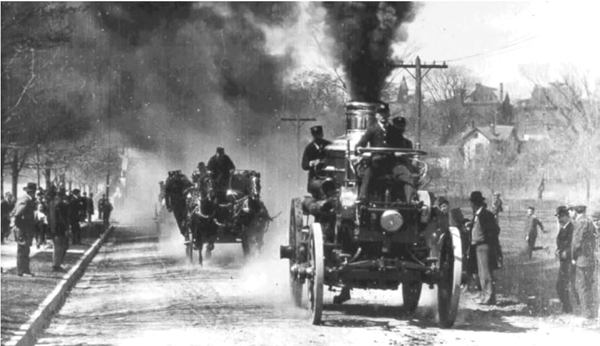

A major thread running through the festival is the year 1897, which, although only the second year of the established film industry, already saw the making of many beautiful and intriguing films. Among the ones shown here were films made by the American Mutoscope Company (later known under the more familiar name, American Mutoscope and Biograph) and British Mutoscope and Biograph. These films, made to be shown in both peepshow machines and projected onto screens, utilized a 68 mm format.

Such films have mainly been seen in poor prints that give an impression of primitive crudeness. Thanks to preservation work on collections in the EYE Filmmuseum and the BFI-National Archive, the richness and clarity of these films have become evident, and they look anything but primitive. One American film (above) is Jumbo, Horseless Fire Engine, credited to William Kennedy-Laurie Dickson himself, provides what must have been an exciting variant on the many films featuring horse-drawn fire engines racing along streets.

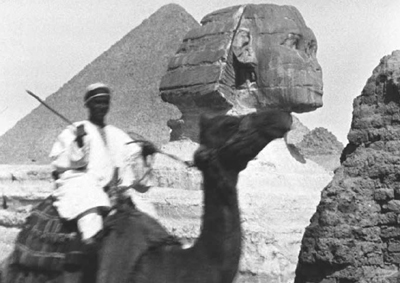

One of the Lumière company’s most prolific traveling cameramen was Alexandre Promio. I was naturally intrigued by series he filmed in Egypt in 1897. One thing that struck me about 28 films in the program was how few featured famous tourist attractions and truly picturesque images. True, Les Pyramides (vue générale) shows one of the most familiar ancient sites in the world, the Sphinx against the great pyramid of Khufu.

Most of the rest of these brief films are remarkably mundane, however. Place de la Citadelle shows an open space with a nondescript building in the distance rather than the two main attractions of the Citadel, the Mosque of Mohammed Ali and the spectacular view out over the city. Village de Sakkarah (cavaliers sur ânes) shows fellahin riding donkeys in modern Mit Rahina, but in the background the colossal quartzite statue of Ramesses II lies on the ground (where it still lies today, covered by a shelter). It is a beautiful statue, visited by nearly all tourists, and yet in the film it is merely a distant, vague shape, identifiable only to those who are familiar with it.

Numerous other views are moving, taken either from trains and showing ordinary industrial buildings or from boats, showing mainly palm trees. The collection leads one to speculate what prompted Promio to choose his subjects.

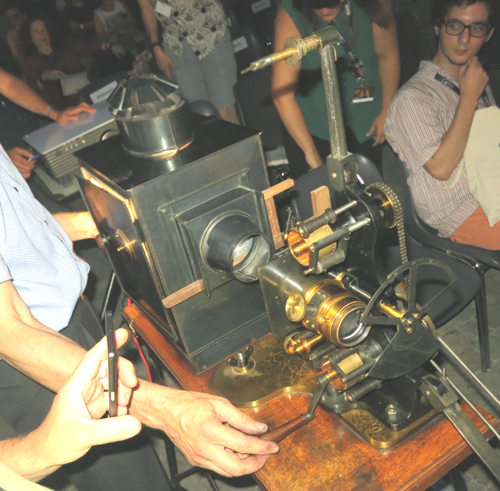

I believe the tradition of showing films in the open air of the Piazzetta Pier Paolo Pasolini (the courtyard of the Cineteca di Bologna) on carbon-arc projectors began in 2013, which I reported on it. This popular feature has expanded, with three programs this year. The first centered around Addio, Giovenezza!, which David described in his entry. The second was particularly special, with a five early shorts ranging from 1902 to 1907 shown on a vintage 1900 projector, hand-cranked by Nikolaus Wostry of the Filmarchiv Austria. The films were charming, but the star of the show was the projector. It looked like a magic lantern dressed up with special attachments that allowed for moving pictures, including a shutter sitting in front of the lens rather than within the body of the lantern. Indeed, the thing looks like a magic lantern converted into a film projector.

This projector cast a much smaller image than the later carbon-arc projector used for the second part of the show. The image had rounded corners and it flickered distinctly. At times, despite Wostry’s obvious expertise at hand-cranking, the image would briefly go to black. Watching this presentation, it became easy to grasp how early audiences might have been constantly aware of the artifice, the machine, creating these images and have marveled at any sort of moving photographs that were cast on the screen before them. It was a magical few minutes, making almost real the section of the program entitled “The Time Machine.”

Classics of 1917

Although there was some thought of ending the Cento Anni Fa programs once the feature film became established, that has fortunately not been done. Instead, a mixture of shorts and features continues to celebrate the cinema of a century ago. Some of the Italian films David wrote about came from that year.

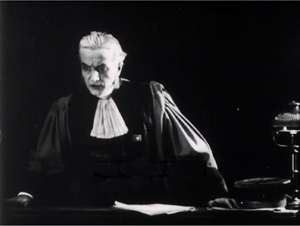

I had the chance to see two masterpieces from that year back to back: André Antoine’s Le coupable and Victor Sjöström’s The Girl from Stormycroft. Both center around the subject of women seduced and left pregnant by their selfish lovers.

I had never seen Le coupable. Antoine is often referred to as a naturalist theatrical director, but going by Le coupable and La terre (1921), he is equally a major film director in the realist tradition, though his output consisted of only nine films from the brief period 1917 to 1922.

While La terre was filmed largely in the countryside, Le coupable was shot in the streets of Paris, and many of its interiors seem to be set in real rooms. Antoine manages to combine the gritty realism of his lower-class milieux with beautiful cinematography (see bottom image). The story takes the unusual form (for its day) of a lengthy series of flashbacks framed by a trial of a young thief and murderer. The past does not unroll from witnesses’ testimony, however, but from one of the presiding judges’ lengthy confession that he is the father of the accused and had abandoned the boy’s mother. The situation is pure melodrama, but Antoine’s light touch and feel for the settings of the action make it a masterpiece.

The Girl from Stormycroft has the distinction of being the first adaptation of a novel by internationally popular author Selma Lagerlöf, whose work was to be the basis for several classics of the Swedish silent cinema, including The Phantom Carriage and Stiller’s The Saga of Gõsta Berling (1924). It is set in the countryside, in a group of small villages. Helga, the heroine, has been seduced by a married man who refuses to acknowledge her child as his own. In a key trial scene, she gives up her suit against him to prevent his committing a sin by swearing to a lie on the Bible. This gains the admiration of a well-off and kind young man, Gudmund, who persuades his mother to take Helga on as a maid. When his fiancée and her parents visit Gudmund’s family, they express disgust at her presence and depart (above), leaving Gudmund is left with doubts about his upcoming marriage.

Early sound films

Il Cinema Ritrovato’s programs offer an opportunity to sample early sound films from a much wider range of countries than usual. Gustav Machaty, best known for Ecstasy (1933), made From Saturday to Sunday in 1931. It follows a pair of working girls who go out to a ritzy nightclub with two wealthy men, intending to exploit the two for a lavish night out while avoiding their sexual demands.

This proves more difficult than they expected, and we end up following one of the pair as she is stranded late at night in the pouring rain. As the title suggests, the action is a slice of life, lasting less than 24 hours. Machaty manages to blend the visual style of the late 1920s with a firm grasp of sound technology. The result is an entertaining if rather conventional tale.

Mexican filmmakers seem to have proved equally adept at taking up sound. The program notes for the program “Rivoluzione e avventura: Il Cinema Messicano dell-Epoca d’Oro” point out that Mexican production burgeoned in the 1930s, going from one feature in 1931 to 21 in 1933.

The earliest film in this thread, El Compadre Mendoza (1933), is a technically and stylistically impressive film, looking like a Hollywood film of the same era. It’s part of a trilogy about the Mexican Revolution, coming between director Fernando de Fuentes’ El prisionero 13 (1933) and Vámonos con Pancho Villa (1935), though it is quite comprehensible and enjoyable on its own.

The irony of the title is that the protagonist, a jovial, sociable plantation owner, is professing loyalty to both sides, and for years he manages to live a pleasant life with his family and staff on their large hacienda. The film is remarkable in portraying the Revolution almost entirely offscreen. The narrative sticks mostly to Mendoza’s house, and we gauge the progress of the fighting purely through a series of sequences in which either revolutionary or government troops ride up the long, tree-lined road to the house. There Mendoza and his household provide a bit of socializing, putting up an effective façade of loyalty to whichever army is present at the time.

Mendoza develops a particular friendship with Felipe, a Revolutionary general (above), who also attracts Mendoza’s young wife in what develops into a lengthy unconsummated romance. Inevitably Mendoza’s juggling of the two sides collapses as he is forced to help one of them against his will.

For me the most unexpected discovery of the festival was the second Mexican film, Two Monks (1934). It is considered the first in the Mexican Gothic genre. It was inspired by the Spanish-language version of Dracula (directed in 1931 by George Melford for Universal), as well as by German Expressionist films.

There are no monsters in the film. Instead, a frame story set in a monastery that looks straight out of Murnau’s Faust (1926) introduces a young monk, Javier, who has gone mad. He attacks another monk, Juan, with a crucifix and confesses to the prior that he did so because Juan had committed a terrible crime. A lengthy flashback lays out the story of Javier’s love for Ana and his eventual rivalry with Juan. In the second half, Juan also confesses, and the story is repeated from his point of view. Scenes we saw earlier are replayed, often starting at an earlier point or ending at a later one, in a way that alters our understanding of the two monks’ past relationship. The result is not a Rashomon-type situation, for the two men agree on the events they describe, disagreeing only on the implications of those events.

It’s a remarkable narrational technique for this early in film history. The atmospheric claustrophobia created by the small cast (no passers-by are seen in the brief street scenes and no servants appear in the houses) and of dread created by the sets and the dissonant music of the climactic scene would bear comparison with the horror films of Universal and Hammer.

Restorations that make me feel old

Film restoration has been around for decades, but at some point within the several years I noticed that an increasing number of films were being restored were ones that I had seen when they first came out or shortly thereafter. Modern classics restoration wasn’t just for silent films and movies from the golden studio era. Now they’re for modern classics: The Graduate, Belle du jour, Women in Love, Blow-Up, and Day for Night (not to mention the restorations shown at Il Cinema Ritrovato in past years).

My first thought is, why do such recent films need restoration? Answer: maybe they’re not as recent as they seem to me. My second thought is, haven’t the studios realized that they need to take care of their films? Answer: Yes, to some extent, given the vital work done by studio archivists like Grover Crisp and Shawn Belston. Still, will There Will Be Blood be neglected until it needs restoration in twenty years’ time?

My first thought is, why do such recent films need restoration? Answer: maybe they’re not as recent as they seem to me. My second thought is, haven’t the studios realized that they need to take care of their films? Answer: Yes, to some extent, given the vital work done by studio archivists like Grover Crisp and Shawn Belston. Still, will There Will Be Blood be neglected until it needs restoration in twenty years’ time?

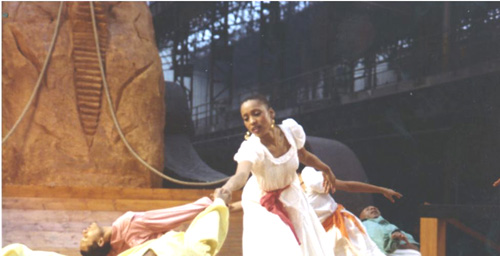

Among the relatively recent films presented in restoration here is Med Hondo’s West Indies (1979). The Film Foundation’s World Cinema Project undertook to restore a number of films by Hondo, a Mauritanian actor and director and one of the most important directors from the African continent.

West Indies is a remarkable film, a musical on the history of French slave-owning in its Caribbean colonies. Inside an empty factory Hondo built a large set depicting the upper and lower decks of a slave ship. The various sections of this ship provide stages upon which scenes, anything from a 1968 demonstration in the streets of Paris to a slave auction hundreds of years before. Five actors representing colonial interests, including a black man who cooperates in order to maintain his position as a figurehead governor, take similar roles throughout the action.

It’s a lively, entertaining film, done in color and widescreen, as well as a maddening look at French complacency and casual cruelty. Most of the musical numbers are dances rather than songs, with Hondo himself having choreographed several of them.

Hondo, now 81 and reportedly seeking backing for another film, was present at the festival and introduced the screening of West Indies that we attended. He was visibly moved by the chance to show this little-known work to an appreciative audience and thoroughly won us over during his brief presentation. With luck we will see a tenth film from him.

Thanks to Guy Borlée for his assistance with this blog, and to the programmers and staff of Ritrovato for another dazzling year. You can download the entire festival catalogue here.

Kelley Conway reviewed Visages Villages at Cannes for our blog.

Le coupable (1917)

Thrill me!

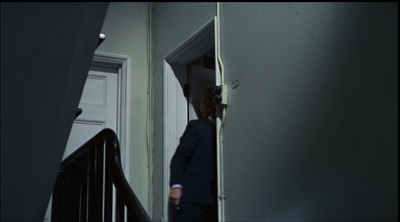

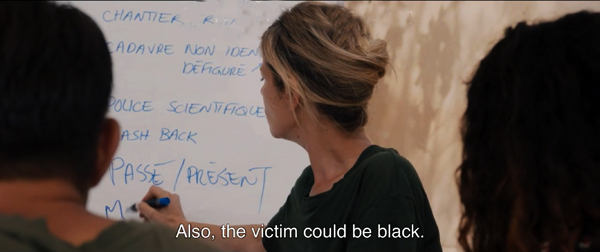

Based on a True Story (Polanski, 2017).

DB here:

Three examples, journalists say, and you’ve got a trend. Well, I have more than three, and probably the trend has been evident to you for some time. Still, I want to analyze it a bit more than I’ve seen done elsewhere.

That trend is the high-end thriller movie. This genre, or mega-genre, seems to have been all over Cannes this year.

A great many deals were announced for thrillers starting, shooting, or completed. Coming up is Paul Schrader’s First Reformed, “centering on members of a church who are troubled by the loss of their loved ones.” There’s Sarah Daggar-Nickson’s A Vigilante, with Olivia Wilde as a woman avenging victims of domestic abuse. There’s Ridley Scott’s All the Money in the World, about the kidnapping of J. Paul Getty III. There’s Lars von Trier’s serial-killer exercise The House that Jack Built. There’s as well 24 Hours to Live, Escape from Praetoria, Close, In Love and Hate, and Extremely Wicked, Shockingly Evil and Vile, featuring Zac Efron as Ted Bundy. Claire Denis, who has made two thrillers, is planning another. Not of all these may see completion, but there’s a trend here.

Then there were the movies actually screened: Based on a True Story (Assayas/ Polanski), Good Time (the Safdie brothers), L’Amant Double (Ozon), The Killing of a Sacred Deer (Lanthimos), The Merciless (Byun), You Were Never Really Here (Ramsay), and Wind River (Sheridan), among others. There was an alien-invasion thriller (Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s Before We Vanish), a political thriller (The Summit), and even an “agricultural thriller” (Bloody Milk). The creative writing class assembled in Cantet’s The Workshop is evidently defined through diversity debates, but what is the group collectively writing? A thriller.

Thrillers seldom come up high in any year’s global box-office grosses. Yet they’re a central part of international film culture and the business it’s attached to. Few other genres are as pervasive and prestigious. What’s going on here?

A prestigious mega-genre

Vertigo (Hitchcock, 1958).

Thriller has been an ambiguous term throughout the twentieth century. For British readers and writers around World War I, the label covered both detective stories and stories of action and adventure, usually centered on spies and criminal masterminds.

By the mid-1930s the term became even more expansive, coming to include as well stories of crime or impending menace centered on home life (the “domestic thriller”) or a maladjusted loner (the “psychological thriller”). The prototypes were the British novel Before the Fact (1932) and the play Gas Light (aka Gaslight and Angel Street, 1938).

While the detective story organizes its plot around an investigation, and aims to whet the reader’s curiosity about a solution to the puzzle, in the domestic or psychological thriller, suspense outranks curiosity. We’re no longer wondering whodunit; often, we know. We ask: Who will escape, and how will the menace be stopped? Accordingly, unlike the detective story or the tale of the lone adventurer, the thriller might put us in the mind of the miscreant or the potential victim.

In the 1940s, the prototypical film thrillers were directed by Hitchcock. I’ve argued elsewhere that he mapped out several possibilities with Foreign Correspondent and Saboteur (spy thrillers) Rebecca and Suspicion (domestic suspense), and Shadow of a Doubt (domestic suspense plus psychological probing). Today, I suppose core-candidates of this strain of thrillers, on both page and screen, would be The Ghost Writer, Gone Girl, and The Girl on the Train.

In the 1940s, as psychological and domestic thrillers became more common, critics and practitioners started to distinguish detective stories from thrillers. In thinking about suspense, people noticed that the distinctive emotional responses depend on different ranges of knowledge about the narrative factors at play. With the classic detective story, Holmesian or hard-boiled, we’re limited to what the detective and sidekicks know. By contrast, a classic thriller may limit us to the threatened characters or to the perpetrator. If a thriller plot does emphasize the investigation we’re likely to get an alternating attachment to cop and crook, as in M, Silence of the Lambs, and Heat.

Today, I think, most people have reverted to a catchall conception of the thriller, including detective stories in the mix. That’s partly because pure detective plotting, fictional or factual, remains surprisingly popular in books, TV, and podcasts like S-Town. The police procedural, fitted out with cops who have their own problems, is virtually the default for many mysteries. So when Cannes coverage refers to thrillers, investigation tales like Campion’s Top of the Lake are included.

In addition, “impure” detective plotting can exploit thriller values. Films primarily focused on an investigation, but emphasizing suspense and danger, can achieve the ominous tension of thrillers, as Se7en and The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo do. More generally, any film involving crime, such as a heist or a political cover-up, could, if it’s structured for suspense and plot twists, be counted as part of the genre.

Yet tales of police detection aren’t currently very central to film, I think. Their role, Jeff Smith suggests, has been somewhat filled by the reporter-as-detective, in Spotlight, Kill the Messenger, and others. Straight-up suspense plots are even more common, as in the classic victim-in-danger plots of The Shallows, Don’t Breathe, and Get Out. Tales of psychological and domestic suspense coalesced as a major trend in Hollywood during the 1940s. It became so important that I devoted a chapter to it in my upcoming book, Reinventing Hollywood: How 1940s Filmmakers Changed Movie Storytelling. (You can get an earlier version of that argument here.)

By referring to “high-tone” thrillers, I simply want to indicate that major directors, writers, and stars have long worked in this broad genre. In the old days we had Lang, Preminger, Siodmak, Minnelli, Cukor, John Sturges, Delmer Daves, Cavalcanti, and many others. Today, as then, there are plenty of mid-range or low-end thrillers (though not as many as there are horror films), but a great many prestigious filmmakers have tried their hand: Soderbergh (Haywire, Side Effects), Scorsese (Cape Fear, Shutter Island), Ridley Scott (Hannibal), Tony Scott (Enemy of the State, Déja vu), Coppola (The Conversation), Bigelow (Blue Steel, Strange Days), Singer (The Usual Suspects), the Coen brothers (Blood Simple, No Country for Old Men et al.), Shyamalan (The Sixth Sense, Split), Nolan (Memento et al.), Lee (Son of Sam, Clockers, Inside Man), Spielberg (Jaws, Minority Report), Lumet (Before the Devil Knows You’re Dead), Cronenberg (A History of Violence, Eastern Promises), Tarantino (Reservoir Dogs, Pulp Fiction, Jackie Brown), Kubrick (Eyes Wide Shut), and even Woody Allen (Match Point, Crimes and Misdemeanors). Brian De Palma and David Fincher work almost exclusively in the genre.

And that list is just American. You can add Almodóvar, Assayas, Besson, Denis, Polanski, Figgis, Frears, Mendes, Refn, Villeneuve, Cuarón, Haneke, Cantet, Tarr, Gareth Jones, and a host of Asians like Kurosawa Kiyoshi, Park Chan-wook, Bong Joon-ho, and Johnnie To. I can’t think of another genre that has attracted more excellent directors. The more high-end talents who tackle the genre, the more attractive it becomes to other filmmakers.

Signing on to a tradition

Creepy (Kurosawa, 2016).

If you’re a writer or a director, and you’re not making a superhero film or a franchise entry, you really have only a few choices nowadays: drama, comedy, thriller. The thriller is a tempting option on several grounds.

For one thing, there’s what Patrick Anderson’s book title announces: The Triumph of the Thriller. Anderson’s book is problematic in some of its historical claims, but there’s no denying the great presence of crime, mystery, and suspense fiction on bestseller lists since the 1970s. Anderson points out that the fat bestsellers of the 1950s, the Michener and Alan Drury sagas, were replaced by bulky crime novels like Gorky Park and Red Dragon. As I write this, nine of the top fifteen books on the Times hardcover-fiction list are either detective stories or suspense stories. A thriller movie has a decent chance to be popular.

This process really started in the Forties. Then there emerged bestselling works laying out the options still dominant today. Erle Stanley Gardner provided the legal mystery before Grisham; Ellery Queen gave us the classic puzzle; Mickey Spillane provided hard-boiled investigation; and Mary Roberts Rinehart, Mignon G. Eberhart, and Daphne du Maurier ruled over the woman-in-peril thriller. Alongside them, there flourished psychological and domestic thrillers—not as hugely popular but strong and critically favored. Much suspense writing was by women, notably Dorothy B. Hughes, Margaret Millar, and Patricia Highsmith, but Cornell Woolrich and John Franklin Bardin contributed too.

I’d argue that mystery-mongering won further prestige in the Forties thanks to Hollywood films. Detective movies gained respectability with The Maltese Falcon, Laura, Crossfire, and other films. Well-made items like Double Indemnity, Mildred Pierce, The Ministry of Fear, The Stranger, The Spiral Staircase, The Window, The Reckless Moment, The Asphalt Jungle, and the work of Hitchcock showed still wider possibilities. Many of these films helped make people think better of the literary genre too. Since then, the suspense thriller has never left Hollywood, with outstanding examples being Hitchcock’s 1950s-1970s films, as well as The Manchurian Candidate (1962), Seconds (1966), Wait Until Dark (1967), Rosemary’s Baby (1968), The Parallax View (1974), Chinatown (1974), and Three Days of the Condor (1975), and onward.

Which is to say there’s an impressive tradition. That’s a second factor pushing current directors to thrillers. It does no harm to have your film compared to the biggest name of all. Google the phrase “this Hitchcockian thriller” and you’ll get over three thousand results. Science fiction and fantasy don’t yet, I think, have quite this level of prestige, though those genres’ premises can be deployed in thriller plotting, as in Source Code, Inception, and Ex Machina.

Since psychological thrillers in particular depend on intricate plotting and moderately complex characters, those elements can infuse the project with a sense of classical gravitas. Side Effects allowed Soderbergh to display a crisp economy that had been kept out of both gonzo projects like Schizopolis and slicker ones like Erin Brockovich.

Ben Hecht noted that mystery stories are ingenious because they have to be. You get points for cleverness in a way other genres don’t permit. Because the thriller is all about misdirection, the filmmaker can explore unusual stratagems of narration that might be out of keeping in other genres. In the Forties, mystery-driven plots encouraged writers to try replay flashbacks that clarified obscure situations. Mildred Pierce is probably the most elaborate example. Up to the present, a thriller lets filmmakers test their skill handling twists and reveals. Since most such films are a kind of game with the viewer, the audience becomes aware of the filmmakers’ skill to an unusual degree.

Thrillers also tend to be stylistic exercises to a greater extent than other genres do. You can display restraint, as Kurosawa Kiyoshi does with his fastidious long-take long shots, or you can go wild., as with De Palma’s split-screens and diopter compositions. Hitchcock was, again, a model with his high-impact montage sequences and florid moments like the retreating shot down the staircase during one murder in Frenzy.

Would any other genre tolerate the showoffish track through a coffeepot’s handle that Fincher throws in our face in Panic Room? It would be distracting in a drama and wouldn’t be goofy enough for a comedy.

Yet in a thriller, the shot not only goes Hitchcock one better but becomes a flamboyant riff in a movie about punishing the rich with a dose of forced confinement. More recently, the German one-take film Victoria exemplifies the look-ma-no-hands treatment of thriller conventions. Would that movie be as buzzworthy if it had been shot and cut in the orthodox way?

Fairly cheap thrills

Non-Stop (Collet-Serra, 2014). Production budget: $50 million. Worldwide gross: $222 million.

The triumph of the movie thriller benefits from an enormous amount of good source material. The Europeans have long recognized the enduring appeal of English and American novels; recall that Visconti turned a James M. Cain novel into Ossessione. After the 40s rise of the thriller, Highsmith became a particular favorite (Clément, Chabrol, Wenders). Ruth Rendell has been mined too, by Chabrol (two times), Ozon, Almodóvar, and Claude Miller. Chabrol, who grew up reading série noire novels, adapted 40s works by Ellery Queen and Charlotte Armstrong, as well as books by Ed McBain and Stanley Ellin. Truffaut tried Woolrich twice and Charles Williams once. Costa-Gavras offered his version of Westlake’s The Ax, while Tavernier and Corneau picked up Jim Thompson. At Cannes, Ozon’s L’Amant double derives from a Joyce Carol Oates thriller the author calls “a prose movie.”

Of course the French have looked closer to home as well, with many versions of Simenon novels by Renoir, Duvivier, Carné, Chabrol (inevitably), Leconte, and others. The trend continues with this year’s Assayas/Polanski adaptation of the French psychological thriller Based on a True Story.

In all such cases, writers and directors get a twofer: a well-crafted plot from a master or mistress of the genre, and praise for having the good taste to disseminate the downmarket genre most favored by intellectuals.

Another advantage of the thriller is economy. There are big-budget thrillers like Inception, Spectre, and the Mission: Impossible franchise. But the thriller can also flourish in the realm of the American mid-budget picture. Recently The Accountant, The Girl on the Train, and The Maze Runner all had budgets under $50 million. Putting aside marketing costs, which are seldom divulged, consider estimated production costs versus worldwide grosses of these top-20 thrillers of the last seven years. The figures come from Box Office Mojo.

Taken 2 $45 million $376 million

Gone Girl $61 million $369 million

Now You See Me $75 million $351 million

Lucy $40 million $463 million

Kingsman: The Secret Service $81 million $414 million

Then there are the low-budget bonanzas.

The Shallows $17 million $119 million

Don’t Breathe $9.9 million $157 million

The Purge: Election Year $10 million $118 million

Split $9 million $276 million

Get Out $4.5 million $241 million

Of course budgets of foreign thrillers are more constrained, and I don’t have figures for typical examples. Still, overseas filmmakers tackling the genre have an advantage over their peers in other genres. Thrillers are exportable to the lucrative American market, twice over.

First, a thriller can be an art-house breakout. Volver, The Lives of Others, and The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo (2009) all scored over $10 million at the US box office, a very high number for a foreign-language film. Asian titles that get into the market have done reasonably well, and enjoy long lives on video and streaming. The Handmaiden and Train to Busan, both from South Korea, doubled the theatrical take of non-thrillers Toni Erdmann and Julieta, as well as that of American indies like Certain Women and The Hollers. Elsewhere, thrillers comprised two of the three big arthouse hits in the UK during the first four months of this year: The Handmaiden, a con-artist movie in its essence, and Elle, a lacquered woman-in-peril shocker.

Second, a solid import can be remade with prominent actors, as Wages of Fear and The Secret in Their Eyes were. Probably the most high-profile recent example was The Departed, a redo of Hong Kong’s Infernal Affairs. Sometimes the director of the original is allowed to shoot the remake, as happened with The Vanishing, Loft, and Hitchcock’s The Man Who Knew Too Much.

Even if the remake doesn’t get produced, just the purchase of remake rights is a big plus. I remember one European writer-director telling me that he earned more from selling the remake rights to his breakout film than he did from the original. He was also offered to direct the remake, but he declined, explaining: “If someone else does it, and it’s good, that’s good for the original. If it’s bad, people will praise the original as better.” And by making a specialty hit, the screenwriter or director gets on the Hollywood radar. If you can direct an effective thriller, American opportunities can open up, as Asian directors have discovered.

Thrillers attract performers. Actors want to do offbeat things, and between their big-paycheck parts they may find the conflicted, often duplicitous characters of psychological thrillers challenging roles. For Side Effects Soderbergh rounded up name performers Jude Law, Rooney Mara, Catherine Zeta-Jones, and Channing Tatum. The Coens are skillful at working with stars like Brad Pitt (Burn after Reading). The rise of the thriller has given actors good Academy Award chances too. Here are some I noticed:

Jane Fonda (Klute), Jodie Foster (Silence of the Lambs), Frances McDormand (Fargo), Natalie Portman (Black Swan), Brie Larson (Room), Anjelica Huston (Prizzi’s Honor), Kim Basinger (L.A. Confidential), Rachel Weisz (The Constant Gardener), Jeremy Irons (Reversal of Fortune), Denzel Washington (Training Day), Sean Penn (Mystic River), Sean Connery (The Untouchables), Tommy Lee Jones (The Fugitive), Kevin Spacey (The Usual Suspects), Benicio Del Toro (Traffic), Tim Robbins (Mystic River), Javier Bardem (No Country for Old Men), Mark Rylance (Bridge of Spies).

Finally, there’s deniability. Because of the genre’s literary prestige, because of the tony talent behind and before the camera, and because of the genre’s ability to cross cultures, the thriller can be….more than a thriller. Just as critics hail every good mystery or spy novel as not just a thriller but literature, so we cinephiles have no problem considering Hitchcock films and Coen films and their ilk as potential masterpieces. On the most influential list of the fifty best films we find The Godfather and Godfather II, Mulholland Dr., Taxi Driver, and Psycho. At the very top is Vertigo, not only a superb thriller but purportedly the greatest film ever made.

I worried that perhaps this whole argument was an exercise in confirmation bias–finding what favors your hunch and ignoring counterexamples. Looking through lists of top releases, I was obliged to recognize that thrillers aren’t as highly rewarded in film culture as serious dramas (Manchester by the Sea, Moonlight, Paterson, Jackie, The Fits). But I also kept finding recent films I’d forgotten to mention (Hell or High Water, The Green Room) or didn’t know of (Karyn Kusama’s The Invitation, Mike Flanigan’s Hush). They supported the minimal intuition that thrillers play an important role in both independent and mainstream moviemaking.

And not just on the fringes or the second tier. Perhaps because film is such an accessible art, all movies are fair game for the canon. As a fan of thrillers in all variants, from genteel cozies and had-I-but-known tales to hard-boiled noir and warped psychodramas, I’m glad that we cinephiles have no problem ranking members of this mega-genre up there with the official classics of Bergman, Fellini, and Antonioni (who built three movies around thriller premises). Of course other genres yield outstanding films as well. But we should be proud that cinema can offer works that aren’t merely “good of their kind” but good of any kind. For that reason alone, ambitious filmmakers are likely to persist in thrill-seeking.

Thanks to Kristin, Jeff Smith, and David Koepp for comments that helped me in this entry. Ben Hecht’s remark comes from Philip K. Scheuer, “A Town Called Hollywood,” Los Angeles Times (30 June 1940), C3.

You can get a fair sense of what the Brits thought a thriller was from a book by Basil Hogarth (great name), Writing Thrillers for Profit: A Practical Guide (London: Black, 1936). A very good survey of the mega-genre is Martin Rubin’s Thrillers (Cambridge University Press, 1999). David Koepp, screenwriter of Panic Room, has thoughts on the thriller film elsewhere on this blog.

Having just finished Delphine de Vigan’s Based on a True Story, I can see what attracted Assayas and Polanski. The film (which I haven’t yet seen) could be a nifty intersection of thriller conventions and the art-cinema aesthetic. As a gynocentric suspenser, though, the book doesn’t seem to me up to, say, Laura Lippman’s Life Sentences, a more densely constructed tale of a memoirist’s mind. And de Vigan’s central gimmick goes back quite a ways; to mention its predecessors would constitute a spoiler. For more on women’s suspense fiction, see “Deadlier than the male (novelist).” For more on Truffaut’s debt to the Hitchcock thriller, try this.

The Workshop (Cantet, 2017).

Wisconsin Fim Festival: An unexpected gem, a Zucchini, and a farewell

Clash (2016)

Kristin here:

Three more films from this year’s Wisconsin Film Festival.

Clash (Eshtebak, 2016)

David and I were intrigued by the festival’s program notes describing Egyptian director Mohamed Diab’s second feature, Clash, as taking place with the camera entirely confined to the interior of a police paddy-wagon. This kind of limitation can be a fruitful device, as it was in the Israeli film Lebanon; there the action took place inside a military tank. Clash turned out to be a real discovery, the best film I saw at the Festival (putting aside A Quiet Passion, which we had already seen at the Vancouver International Film Festival.).

Diab’s paddy-wagon has the advantage of rows of barred windows and a door, so that we can frequently see what’s happening outside. The film is set in the summer of 2013, when there were protests, often turning violent, in the wake of the ouster of President Mohamed Morsi and his replacement by the current president, Abdel Fattah el-Sisi. The truck moves through Cairo, encountering waves of such protests, and it gradually fills with a collection of people with various religions, beliefs, and cultures–supporters of Morsi’s party, the Muslim Brotherhood; others who oppose him; Christians; a homeless man; a nurse; and two journalists–with arguments and violence erupting inside the vehicle as well as outside.

Diab had to tread a fine line in his depiction of these people, since his basic theme is that they all must learn to cooperate to some extent if they hope to survive the baking heat, tear gas, gunfire, police bullying, and the anger of the mobs outside the truck. Officially the Muslim Brotherhood is considered a terrorist organization in Egypt, though Diab manages a fairly even-handed treatment of its members and supporters. Remarkably the censors did not require any changes to the film.

Just as remarkably, Diab was able to stage huge, convincingly terrifying riots in Cairo’s streets and highways (above). In a brief interview at Cannes last year, where Clash was shown in the Un Certain Regard section, he was asked if the shoot was difficult.

Very. You are risking your life because people might mistake the shoot for a protest, or might mistake you for the police. And there are haters of both, who can shoot you. It took us months of preparation. Egyptians to whom I’ve shown the film are blown away because they know that what we did is almost impossible.

He makes similar remarks in a question-and-answer session at the London Film Festival; his discussion of the film’s techniques comes from about 9:30 to 13:50.

The characters in the truck are constantly in danger, both from each other and from the rioters, and the action is absolutely riveting. There are a few lulls to vary the pace and to allow the prisoners to deal with their wounds and try to work out a strategy to protect themselves, but otherwise the suspense is maintained at a high level. A climactic scene in which rioters attack the truck, flashing laser pointers into it and trying to tip it over is handled, as Variety‘s review put it, with “brilliantly choreographed pandemonium.”

Clash was a huge success in Egypt. It was released in France in September and is already out on region 2 DVD (French subtitles only) there. Its festival life seems to be drawing to a close. It’s due for theatrical release in the UK and Ireland on April 21 and presumably will come out on Blu-ray and/or DVD. You can get a good sense of the film from the online trailers, the European one and especially the Egyptian one, though the film is not nearly so fast-cut.

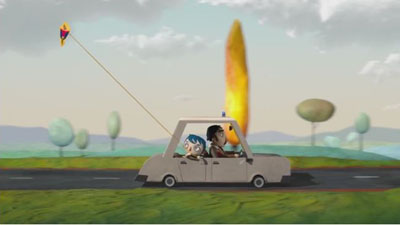

My Life as a Zucchini (Ma vie de courgette, 2016)

2016 was a good year for animation. Kubo and the Two Strings, The Red Turtle, Moana, and Finding Dory were excellent as well. (I thought Zootopia was overrated.) Add My Life as a Zucchini to that list. This being Madison and the Wisconsin Film Festival being a university-sponsored event, we saw it with French subtitles rather than dubbed.

The style of the film, with its bright colors and cute, big-headed characters (above and at the bottom), makes it seem aimed at children, and the story is presented almost entirely through the viewpoints of Zucchini and the other children he meets. Yet children younger than teenagers would probably find parts of it incomprehensible or disturbing. The boys indulge in naïve but somewhat explicit speculation about sex. Zucchini’s beer-swilling mother apparently dies in an accident that he inadvertently causes, though this happens offscreen. He is taken by a sympathetic policeman to a small home for young children in the countryside. Not all are orphans, as it is made clear that one girl was taken away from her sexually abusive father and some of the others come from homes ruined by addiction or violence. Zucchini gets bullied and teased before finally being accepted.

All this makes for a strain of melancholy running through the film, but there is considerable humor to counter it, and the ending is happy.

Like Kubo, My Life as a Zucchini is puppet animation. Clearly it was done on a much lower budget, without the laser-printed changeable faces that make Laika’s characters so expressive. Charmingly, if distractingly, the clothes of the puppets occasionally shift positions, betraying the handling by the animators between frames–as when the red star on Zucchini’s T-shirt inadvertently takes on a life of its own. But on the whole, the filmmakers have used simple means to give their figures considerable expressivity.

The nomination of My Life as a Zucchini for the Best Animated Feature Oscar came as something of a surprise. Foreign films do show up in that category, but this one had its widest American release in a mere 53 theaters. It came out on February 24 and is still in 22 theaters, having grossed $286,154 as of April 6. (Presumably that does not count the two WFF screenings; the one we went to was sold out.) The DVD and Blu-ray versions are available for pre-orders on Amazon. The description says that both the original French-language soundtrack and the English-dubbed one are included.

Afterimage (Powidoki, 2016)

Afterimage premiered at the Toronto Film Festical almost exactly a month before the death of director Andrzej Wajda. It deals with the co-founder of Polish Constructivism, Wladyslaw Strzeminski, who helped create the Blok group in Warsaw in 1923. The plot covers only Strzeminski’s last years, but we get a strong sense of his entire career through gallery scenes displaying his work.

Socialist Realism was imposed upon Polish artists after the country came under the sway of the USSR in the wake of World War II. The film’s action starts with Strzeminski’s being fired in 1950 by the Ministry of Culture and Art because he refused to adhere to the doctrine. We see his stubborn resistance and the attempts by his adoring students to help him find respect and other work. Up to his death in 1952, he is oppressed by intransigent officials bent on denying him even the most demeaning jobs.

Reviewers have treated Afterimage with the respect due a veteran auteur late in a six-decade-plus career, but they deem it to lack the energy and appeal of his earlier work. Certainly compared with Wajda’s films of the 1950s and 1960s (we’ve commented briefly on two from the 1960s), Afterimage is a fairly conventional film. It’s beautifully made, as Wajda clearly had a considerable budget to recreate the historical look of Soviet-era buildings and streets of the early 1950s. To anyone unfamiliar with the impact that Socialist Realism could have on the avant-garde artists in the USSR and elsewhere starting in the 1930s, the film provides a vivid example. The film also contains an excellent performance by Boguslaw Linda, perhaps best known as the lead in Kieslowski’s Blind Chance.

Strzeminski, being the victim of persecution from almost the beginning, automatically becomes a sympathetic character. He also lost an arm and a leg in 1916 during World War I. (The budget is on display again in the fact that undetectable special effects removed Linda’s own arm and leg.) It is hinted that if he had been grievously injured in World War II, some allowances might be made, but having it happen during the Tsarist war of the pre-revolutionary era earns him no credit with the officials.

Yet Strzeminski loses some of our sympathy through his treatment of his teenage daughter Nika. She is interested in his art, closely examining the “Neoplastic Room” he helped create in the Lodz Museum–just before it is dismantled and put into storage as part of Strzeminski’s punishement. Nika also tries to help her father, cooking for him and trying to get him to cut back on smoking, but his ingracious rejection of her efforts helps drive her to live in a girls’ dormitory near her school. He remarks matter-of-factly after Nika leaves, “She will have a hard life.”

Our thanks to Graham Swindoll of Kino Lorber for help with this entry. As well, of course we owe a debt of gratitude to the WFF programmers Jim Healy, Mike King, and Ben Reiser.

My Life as a Zucchini (2016)