Archive for the 'Directors: Tati' Category

Il Cinema Ritrovato: Strands from the 1950s and 1960s

Faraon (1966).

Kristin here:

David has already posted an early report on his first full day at Il Cinema Ritrovato in Bologna. It conveys something of the overwhelming abundance of offerings at this year’s festival. Writing another entry during the festival itself proved impossible, given our packed schedules, but now we have time to catch our breath and reflect on what we were able to see.

As with the 2013 festival, I decided that the only way to navigate the many simultaneous screenings was to pick out some major threads and stick with them. I chose the retrospective of Polish widescreen films of the 1960s, that of Indian classics from the 1950s, and the third season of early Japanese talkies. Miraculously, none of these conflicted with each other, the Polish films being on mainly in the mornings, the Japanese ones directly after the lunch break, and the Indian films starting late in the afternoon.

Again, it was possible to fit in a few films from the other programs on offer, including a series of Germaine Dulac’s films, restorations of East of Eden and Rebel without a Cause, a selection of Riccardo Freda’s work, Italian contributions lifted from various anthology films of the 1950s and 1960s, a celebration of the 50th anniversary of the Österreichisches Filmmuseum, and many Chaplin shorts (the festival was preceded by a brief conference on Chaplin).

The annual Cento Anni Fa program, showing films from 100 years ago, has changed, in part to accommodate the fact that the transition to feature films was well underway. The series programer, Mariann Lewinsky, has also branched out. Having discovered many unknown or little-known early silents during her annual quests, she has included other brief thematic programs, such as fashion in early films. In addition, there was a lengthier selection of early films dealing with war, given that we are now in the centenary of World War I.

A Journey from Pole to Pole

The Saragossa Manuscript (1965).

To me the biggest revelation of the festival was the program of Polish anamorphic widescreen films. Representing most of the major Polish directors working in widescreen in the 1960s, these were shown in 35mm, mostly in original release prints from the period, on the big screen of the Cinema Arlecchino theatre. Despite occasional wear in the prints, they looked great.

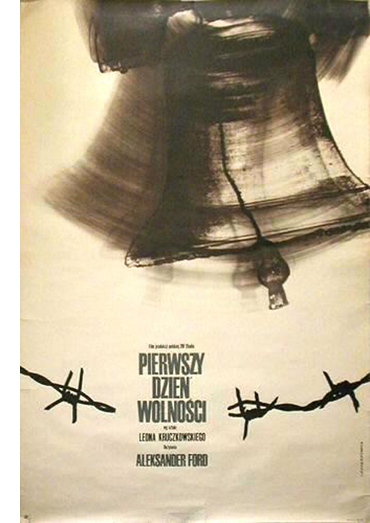

The series kicked off with Aleksander Ford’s little-known The First Day of Freedom (Perwszy dzień wolności, 1964). Like many of the films in the program, it dealt with World War II. Polish soldiers, escaped from a POW camp, enter a nearly deserted German town. They disagree on whether to help protect the civilians they encounter or participate in the general rape and pillage in the wake of the Nazi retreat. It’s a grim and realistic look at a topic seldom tackled in films about the war.

Also on the program was Andrej Munk’s Passenger (Paseżerka, 1963), left unfinished when the director was killed in a car accident. His colleagues eventually decided to assemble the film without additional footage, drawing upon still photos for some scenes and an effective voiceover filling in the action. The effort works well, and the result is a powerful examination of a Nazi death camp. The story does not concentrate on Jews but on political prisoners, implicitly communists and other rebels. The result is the sort of disguised political comment on Poland’s contemporary situation that is common in these films.

Early on, a middle-aged woman aboard a ship tells her companion about her life in as an official in the camp–a story that is contradicted when the actual scenes of her activities at the camp play out. The woman singles out a female prisoner, Marta, and rationalizes her irrational mixture of rewards and punishments as efforts to save her from the other prisoners’ fates. With its depictions of cat-and-mouse games between prisoners and captors and its references to mysterious sadistic rituals played out by the guards, the film is a powerful meditation on the camps, worthy, as Peter von Bagh’s program notes say, to sit alongside Resnais’s documentary, Night and Fog.

Among the unexpected delights of the series was Lenin in Poland (Lenin w Polsce, 1966) by Sergei Yutkevich (or, as he is credited here, Jutkevič). Yutkevich began as a member of the Soviet Montage movement, contributing a little-known, late feature, Golden Mountains (1932). Working in Poland, he managed the formidable task of humanizing Lenin in unorthodox ways. Yutkevich concentrates on the leader’s Polish exile on the eve of World War I. Framed by Lenin’s brief imprisonment on charges of espionage, the film proceeds through flashbacks to his recent activities. As portrayed by Maksim Strauch, whose resemblance to the revolutionary leader gave him a long career in numerous films, Lenin is humorous, kind, thoughtful, and a likeable protagonist. Yutkevich includes touches from the Montage movement, with some passages of quick cutting and frequent heroic framings of the protagonist.

With my interest in ancient Egypt, I was particularly curious about Faraon (Pharaoh, Jerzy Kawalerowicz, 1966). The director tackles the unusual and obscure topic of the end of the 20th Dynasty, which led to the end of the golden age of the New Kingdom and the instability of the Third Intermediate Period. The film’s drama comes from the real-life conflict between the impoverished, weakened monarch and the wealthy, powerful priests of Amun in Thebes. I’m not sure how well an audience not familiar with this era would follow the plot, even simplified as it is. There are some remarkable crowd scenes, as at the top of this entry, when Herhor, the chief of the priests, rallies the crowd against the pharaoh. Still, I did not find the story engaging. Presumably it was a covert commentary on politics in Poland at the time.

The best-known of Polish directors, Andrzej Wajda, was represented by two films. One was the earliest film shown in the series, Samson, from 1961. It concerns a young Jewish man who is lured to escape from the Warsaw Ghetto and spends most of the film dodging the police by moving from one temporary haven to another. Wajda creates a compelling depiction of the ghetto early on, and I wished he had stayed in that environment longer.

My favorite film of the festival was Wajda’s little-known Ashes (Popioły [not to be confused with Ashes and Diamonds], 1965), an epic tale of the Napoleonic wars and Poland’s unwise participation in them on the side of the French. The protagonist, Rafal Olbromski, is a naive young nobleman from a rural area, a Candide-like figure whom we follow as he leaves his estate to go to war and moves from locale to locale, manipulated by more sophisticated characters. The result is a dizzying succession of battle scenes, largely without any context being established, punctuated by visits to the estates of those who are backing the Polish participation in Napoleon’s conquests. Wajda seemed to have had nearly limitless funds for the film, and the battle scenes are monumental.

Far less obscure is Wojciech Has’s The Saragossa Manuscript (Rękopis znaleziony a Saragossie, 1965), a cult item among film buffs and reputedly one of Luis Buñuel’s favorite films. It’s a complex, surreal tale of a wandering soldier of the 18th Century who passes the gibbets of two executed men in a bleak Spanish landscape and enters a mysterious inn. There he encounters a large bound manuscript that leads him into a world of shifting fantasy and tales within tales within tales. Has’s was certainly one of the most humorous and entertaining films in the series.

The latest film in the program, Adventure with a Song (Przygoda z piosenka, Stanisław Bareja, 1969), was radically different from the others and provided a look at popular Polish cinema of the 1960s. Bareja was a successful director of comedies and musicals. This one follows a young singer who wins a local singing contest with the improbably named “The Donkey Had Two Troughs,” and decides to head for a professional career in Paris. The filmmakers’ attempts to replicate the Mod styles and garish colors of the 1960s in the West yield an incongruous and awkward but fascinating film .

The one disadvantage of seeing these vintage distribution prints (mostly with English subtitles) was that some were abridged versions, occasionally radically so. Samson, The First Days of Freedom, Adventure with a Song, and, inevitably Passenger were shown complete. Judging by imdb’s timings, however, others were missing significant amounts footage: Ashes (shown at 169′, originally 234′), The Saragossa Manuscript (155′ vs. 175′), Pharaoh (149′ vs. 180′).

Recently there seems to be a revival of interest in Polish classic films. Martin Scorsese has curated a large program that is currently touring the US with digital copies of restored films. (For links to numerous articles on the series and the restorations, see its Facebook page.) I hope that some enterprising company will issue the complete versions of these Polish classics in their proper widescreen ratios. Ashes is a particularly good candidate for such treatment. Having sat through it once at nearly three hours, I would happily watch it at closer to four.

Worthy of restoration

There’s a growing interest in recent Indian films, at least in the USA. Our biggest local multiplex nearly always devotes  one screen to a Bollywood musical, and sometimes two. Yet few know the great classics of the early post-colonial period in India, following World War II and independence from Great Britain, which are seldom seen, even by film historians.

one screen to a Bollywood musical, and sometimes two. Yet few know the great classics of the early post-colonial period in India, following World War II and independence from Great Britain, which are seldom seen, even by film historians.

One reason is because many of these classics still await restoration. While most programs shown in Bologna consist of newly restored prints, this series was titled “The Golden 50s: India’s Endangered Classics.” Each of the features was accompanied by an episode of “Indian News Review,” a newsreel that for years was shown in film programs across India. Shivendra Singh Dungarpur, founder of the Film Heritage Foundation, curated the series and introduced each film, emphasizing that even the eight classics selected for the program are in danger if not properly restored soon.

The need was evident from the prints. Some were old distribution prints, but three of the films could only be shown on Blu-ray. Even under these conditions, however, the range and quality of Indian cinema of the 1950s was apparent.

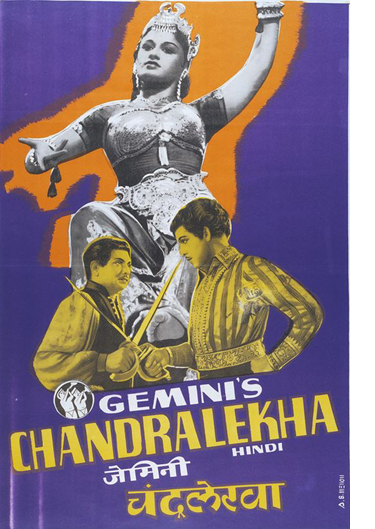

The earliest film in the series, Chandralekha (S. S. Vasan), was made a little before that decade, in 1948. Its presence stems from its crucial importance in Indian film history. It was the first big, successful Indian musical of the post-colonial era and set the pattern for many of the country’s subsequent films. The story has a fairy-tale setting, with a good and an evil brother fighting over the throne of their father’s kingdom and also for the hand of the beautiful Chandralekha. The rambling plot includes lots of songs and dance numbers, leading up to the climactic, legendary Drum Dance (below right), with dozens of dancers atop rows of enormous drums. It lives up to expectations. (For more on Chandralekha, see fellow Ritrovato fan Antii Alanen’s epic blog post.)

David has already described seeing the sole Raj Kapoor film in the series, the very popular Awara. Bimal Roy’s Two Acres of Land (Do Bigha Zameen, 1953) is a very different sort of film. Quite consciously inspired by Bicycle Thieves, Roy’s film eschews the standard musical numbers and deals with a poor farmer destined to lose his small farm unless he can pay off a large debt. His journey to Kolkata, with his son trailing after, throws obstacle after obstacle in his path, and Roy avoids a happy ending. The film was shot on the streets of Kolkata, which Dungarpur assured us have not changed much since this record of them.

David has already described seeing the sole Raj Kapoor film in the series, the very popular Awara. Bimal Roy’s Two Acres of Land (Do Bigha Zameen, 1953) is a very different sort of film. Quite consciously inspired by Bicycle Thieves, Roy’s film eschews the standard musical numbers and deals with a poor farmer destined to lose his small farm unless he can pay off a large debt. His journey to Kolkata, with his son trailing after, throws obstacle after obstacle in his path, and Roy avoids a happy ending. The film was shot on the streets of Kolkata, which Dungarpur assured us have not changed much since this record of them.

One of the great Indian directors, Ritwik Ghatak, has become somewhat familiar in the West, thanks in part to the British Film Institute’s issuing two of his masterpieces on DVD: A River Called Titas and The Cloud-Capped Star. The series at Bologna included Ghatak’s first feature, Ajantrik (1957). It is set among the poverty-stricken Oraons, an isolated population in Central India, and follows a man who is devoted to his dilapidated taxi, which he manages to hold together well enough to supply him a marginal living. He has come to think of the car as a human companion. (Accordingly, the title means, roughly, “not mechanical,” although for western distribution it was given the unenticing title Pathetic Fallacy.) Though Ajantrik is not a major film on the level of the others in the program, it was good to have the rare opportunity to see Ghatak’s first film.

The star of the series was undoubtedly an equally respected director, Guru Dutt. Two of his films, in both of which he also starred, were shown. One of his finest films, Pyaasa (The Thirsty One, 1957), was perhaps the best film of the program. Dutt is considered to have integrated the conventional song episodes of Indian cinema into his films more skillfully and in more original ways than other directors.

Dutt plays a great but unappreciated poet whose work is ignored by the intelligentsia of his own class. He wanders in despair among the poor and outcast, for whom he has great sympathy. In one haunting scene, he walks through a brothel district and sings of his despair for humanity (below). Early in the film he meets a prostitute who appreciates his poetry and falls in love with him. Only after the poet’s apparent death does his work become widely loved among the the common people, but his reputation is exploited by his hypocritical family and publisher.

Dutt’s Kaagaz Ke Phool (Paper Flowers, 1959), was also shown. Again Dutt plays an unappreciated artist. A film director divorces his wife and becomes the target of gossip when he casts a beautiful young actress in his next movie. His personal misery affects his ability to direct, and after a slow slide into alcoholism, he loses his job. The plot allows Dutt to express self-pity more obviously than in Pyaasa, and the comic scenes with his ex-wife’s family strike an odd tone in such a grim story. Kaagaz Ke Phool was not a success, and Dutt gave up filmmaking altogether, dying of an overdose of sleeping pills five years later. As Dungparapur pointed out, he was one of several important Indian filmmakers who died rather young, which makes the rescue of these classics all the more essential.

Pyaasa (1957).

Recovered, discovered, and restored: DVDs, Blu-rays, and a book

Gipsy Anne (1920).

Kristin here:

A stack of new DVDs/BDs and books has been gradually building up on the floor in a corner of my study. I’ve been meaning to blog about them, but first I had to catch up with viewing and reading. Or did I? With this year’s Il Cinema Ritrovato starting next week, I suddenly realized that the DVDs at the bottom of the pile were ones I bought there last year! Clearly, I would never catch up.

So this entry aims to notify you of releases, many obscure, that you may so far have missed. Mostly the DVDs and BDs come from the dedicated archives and independent home-video companies that release historical rarities and restorations.

Early Scandinavian films

I don’t think I had ever seen a Norwegian silent film, apart from the one Carl Dreyer made there, Glomdalsbruden (The Bride of Glomdal, 1925). Though produced between Master of the House and the wonderful La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc, The Bride of Glomdal is unquestionably one of Dreyer’s lesser works.

In the sales room at last year’s Il Cinema Ritrovato, one stand was selling four new releases of Norwegian and Swedish silent and early sound films. All were issued by the Norsk FilmInstitutt.

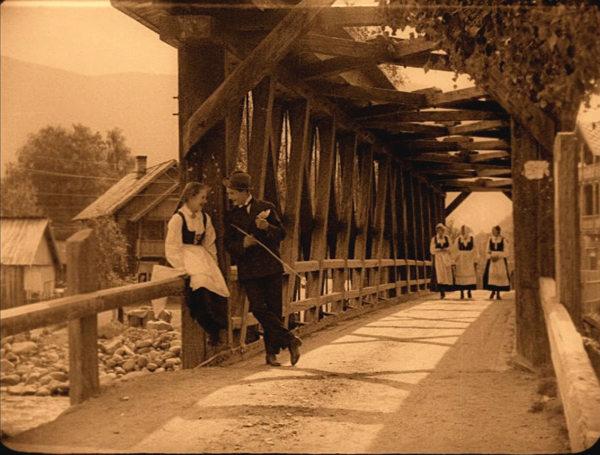

Of these, the most important seems to be Fante-Anne (Gipsy Anne), directed in 1920 by Rasmus Breistein. It’s generally considered the first Norwegian feature film, launching the genre of the rural melodrama that would be a mainstay of the industry.

Of these, the most important seems to be Fante-Anne (Gipsy Anne), directed in 1920 by Rasmus Breistein. It’s generally considered the first Norwegian feature film, launching the genre of the rural melodrama that would be a mainstay of the industry.

This is the only one of these Norwegian films that I have so far watched, and it’s a remarkable one. Clearly Breistein and his cinematographer Gunnar Nilsen-Vig were influenced by the great Swedish films of Sjöström and Stiller, and though Gipsy Ann is not up to the best work of those two, it shares the same feeling for landscape for for allowing a melodramatic situation to develop slowly and in unexpected ways.

It tells the story of a foundling child, Anne taken in by a widow who owns a large farm and who raises the girl alongside her son, Haldor. Haldor is a timid boy, constantly led astray by the adventurous Anne. Once they grow up, the two fall in love, but Haldor’s mother pushes her son into an engagement with a young woman from a well-to-do family. In the meantime, Jon, a humble tenant farmer working for the widow, falls in love with Anne, who snubs him.

Gipsy Anne has none of the clumsiness in lighting and staging that one so often sees in European films of the period around 1920. The cinematography is beautiful, as the frame at the top shows. Breistein has mastered shot/reverse shot and other aspects of analytical editing. The lighting is impressive, with some interiors using a strong backlight through windows and a soft fill that gives a sense of realism (left).

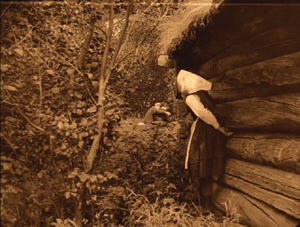

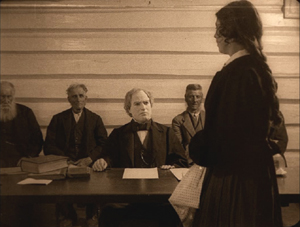

The film also sets up neat visual parallels. In a scene in Anne’s childhood (below left), she hides by an old farm building and curiously spies on some local lovers. Much later, she lurks heartbroken by Haldor’s lavish new house as he shows it to his fiancée:

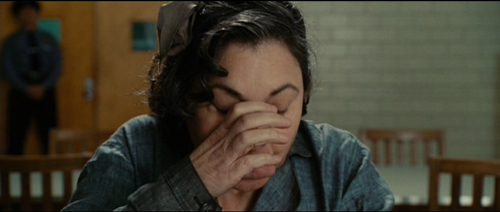

There are even some planimetric shots that yield dramatic compositions, one when Jon comforts the young Anne when she learns that she was adopted, and another, much later, when Anne is in court testifying about the fire that burned down Haldor’s new house:

Again there is a parallel, since Anne is hiding her own guilt in starting the fire, and Jon is about to falsely confess to the crime to protect her. (There’s also a hint at influence from Dreyer in that courtroom shot.)

Of the four releases, Fante-Anne is the only one put out in a Blu-ray version, packaged along with a DVD and an informative booklet in Norwegian and English. The print, with toning and a pleasantly rustic-sounding score, has English subtitles. Oddly enough, the Norsk Filminstitutt does not have an online shop. The film is available from at least two Norwegian online dealers in Scandinavian videos, Nordicdvd and Dvdhuset. It can also be ordered from an American source, Blu-ray.com.

Markens Grøde (The Growth of the Soil) was made only a year later, in 1921; it was directed by Gunnar Sommerfeldt and is another rural melodrama, adapted from a Nobel Prize-winning novel of the same title. This release is 89 minutes long and includes subtitles in English, French, Spanish, German, and Russian. It, too, can be ordered from Nordicdvd and DVDhuset.

The third release is an epic film, Brudeferden i Hardanger (The Bridal Party in Hardanger, 1926). Its two parts run 104 and 74 minutes; it was also directed by Rasmus Breistein, with cinematography by Gunnar Nilsen-Vig. DVDhuset carries it, but not Nordicdvd. It is, however, available from Amazon.uk. It has English subtitles.

Finally there is “Bjørnson på film,” a compilation of three early films based on the pastoral writings of Nobel Prize-winning author Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson and was issued in 2010, the centenary year of the author’s death. Two of these are Swedish productions: Synnøve Solbakken (1919, director John W. Brunius) and Et Farlig Frieri (A Dangerous Proposal, 1919, director Rune Carlsten). Lars Hansen stars in both, and Karin Molander co-stars in Synnøve Solbakken. The third is an early Norwegian talkie, En Glad Gutt (A Happy Boy, 1932, director John W. Brunius).

After considerable searching, I can find no online source for this 2-DVD set. Perhaps it will become available. Otherwise you’ll have to come to Il Cinema Ritrovato and see if it’s on sale again. If not, at least you will have a great time!

All these releases are PAL, though Fante-Anne is also Blu-ray region B; they would all need to be played on a multi-standard machine.

(Mostly) American treasures

The well-known and invaluable “Treasures” series from the National Film Preservation Foundation has become somewhat difficult to keep track of. It started with “Treasures from American Film Archives: 50 Preserved Films.” That was followed by “More Treasures from American Film Archives: 1894-1931.” After that volume numbers appeared, and the references to archives were dropped in favor of thematic collections: “Treasures III: Social Issues in American Film 1900-1934” and “American Treasures IV: Avant Garde 1947-1986.” Then Roman numerals disappeared with “Treasures 5: The West 1898-1938.”(The ones linked are still in print.)

Now we have an unnumbered entry, but it’s still part of the series: “Lost & Found: American Treasures from the New Zealand Film Archive.” Most readers will recall that in 2010 it was announced that about 75 films had been found in the New Zealand Film Archive. News coverage mostly centered on John Ford’s 1927 feature Upstream, which had up to that point been lost. That film forms the central attraction for this new release.

It also includes, however, an incomplete print of a distinctly non-American film, The White Shadow (1924). It was directed by Graham Cutts, but it is mainly of interest now as a film on which the young Alfred Hitchcock worked in several capacities. He wrote the script, based on a novel, and was assistant director, editor, and art director. Despite the enthusiastic tone of the program notes in the booklet accompanying this set, there is little detectable of the later Hitch. The story is ludicrously far-fetched, depending on the old good twin/bad twin contrast, with Betty Compson in both roles (above). At various points the twins pretend to be each other, much to the confusion of the bad twin’s fiancé, played by Clive Brook. The convoluted plot becomes even more so when a series of titles tries to convey the action of the missing final three reels.

The film has its moments. Cutts, who was a decent if not outstanding director, manages some lovely compositions, as with the backlighting in the night interior below left. As with many of Hitchcock’s sets for the film, this one is pretty standard-issue. He obviously had some fun with the set for the tavern called The Cat Who Laughs. It looks a bit jumbled, but it’s actually full of little areas that Cutts uses effectively for picking out pieces of action amid the chaos:

So the Treasures series moves on, as does the Foundation. Not all of the discovered prints made it onto the DVD set. Several more have been preserved since and generously made available for free online viewing at the Foundation’s website; more will be added as the restorations are completed.

Blu-ray USA

American classics continue to make their way onto BD.

Flicker Alley has teamed with the Blackhawk Films Collection to release The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1923, director Wallace Worsley). No original 35mm negative or print is known to survive, so this release was mastered from a 16mm tinted copy struck at some point from the original negative. Some restrained digital restoration was done to clean it up a bit. The extras include an essay and audio commentary by Michael F. Blake and a 1915 film, Alas and Alack, with Chaney in his pre-movie star days playing a hunchback.

The film is available at Flicker Alley’s website, where you can also pre-order their three upcoming releases: a set of all Chaplin’s Mutual Comedies (1916-17); the first volume of The Mack Sennett Collection, including 50 films; and We’re in the Movies, which collects some early local films made by itinerant moviemakers, as well as Steve Schaller’s 1983 documentary, When You Wore a Tulip and I Wore a Big Red Rose, about the first film made in Wisconsin. There’s also a documentary about a small local theater in Los Angeles that showed silent films in the sound age.

D. W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation will celebrate its centennial next year, and now it’s also out on Blu-ray, from both Kino Classics in the USA and Eureka! in the UK. Both have the same new restoration from 35mm elements accompanied by the same score. The extras also appear to be identical–most notably seven Biograph shorts by Griffith about the Civil War. The main difference is that Kino throws in David Shepard’s 1993 restoration, with different musical accompaniment and a 24-minute documentary on the making of the film. Again, the Eureka! version is BD region B.

Last month Eureka! also released a BD of Billy Wilder’s Ace in the Hole (1951, BD region B) in their “Masters of Cinema” program. The release also contains a DVD version. You can check it out, along with other recent releases and upcoming ones here.

Edition-Filmmuseum

This German series works with an impressive array of archives, mostly German but also Swiss and Luxembourgian. The titles that result include modern films (Straub and Huillet figure in their catalogue, as does Werner Schroeter), television, experimental cinema (they’ve done several James Benning films), documentaries, and older films. (No Blu-ray as of now. Perhaps too expensive or perhaps just the sort of restraint that dictates the white backgrounds on their covers.)

Recently Edition-Filmmuseum released a set with two films by Gerhard Lamprecht, a little-known and but in the 1920s an important director of socially conscience films set among the working class. The two-disc release includes Menschen untereinander (1926) and Unter der Laterne (1928), each with two musical tracks to choose from. The German intertitles are subtitled in English and French, and the enclosed booklet is likewise trilingual. Like all the DVDs from this company, there is no region coding.

Similarly, another new release is devoted to the early films of Michail Kalatozov, a Georgian director better known for his Soviet films of the 1950s and 1960s (e.g., The Cranes Are Flying and I Am Cuba). One of the films here is Salt for Svanetia (1930), one of those vaguely familiar but rare titles from the history books on Soviet montage cinema. The other is Nail in the Boot (1932).

Salt for Svanetia is indeed a classic that anyone interested in silent cinema and the Soviet Montage movement should see. Set in an extremely isolated, primitive area of the Caucasus, Svanetia obviously needs a dose of Soviet modernizing. The peasants can barely subsist, and a lack of salt makes their cows and goats unable to produce milk. It’s basically an attempt to combine an ethnographic documentary with large doses of Montage-style rapid editing, canted cameras, heroic framings of people against the sky. At one point a man cutting another’s hair is framed against one of the local feudal era towers in a low angle that makes it look like something out of Alexander Nevsky (above). The film is a fascinating peep into a little-known culture.

Kalatozov stages some sketchy scenes using the locals: an avalanche which kills some men, a resulting funeral, a woman giving birth alone in the countryside. There’s no over-arching plot, though, and the director wisely sticks with showing off local customs. Naturally at the end the Soviets are building a long road to reach the area, and there’s a promise of good things to come.

Nail in the Boot is impressive for about two-thirds of its length. It stages some large battle scenes between what I take to by the Red and White Armies during the Civil War. The Whites are attacking an armored train, and a lot of explosions result. The soldiers aboard the train fire machine-guns, and Kalatozov conveys the sound by alternating single-frame shots of the muzzle of the gun with single-frame shots of the man firing it. Sound familiar? It happens two or three more times in the course of this film. Both of these films are definitely part of the Montage movement, but the director has come along so late in it that he seems to feel all the good ideas have been used, and they’re worth using again. So we get another quotation from October in a canted shot of a cannon’s wheel, and Kalatozov even steals the idea of our hero looking and feeling very small and his prosecutor becoming a looming giant, as in Kozintsev and Trauberg’s The Overcoat:

We are some time into the film before we meet the hero, and I was thinking that this might be one of those Montage films with no single central figure. But well into it, the ammunition on the train is running out, and a messenger is sent to run and get help. Much of the film simply shows him running along, becoming increasingly lame as a bullet in his boot digs into his foot. Ultimately he does not reach his goal, though he tries hard. Once he is put on trial for treason, he blames the shoddy workmanship of the cobblers who made his boot badly. This seems a strange anti-climax after the exciting battle scenes earlier on, but the film actually turns out to be about Soviet workers paying attention to what they’re doing and not putting out a bad product. All the workers looking on at the trial look shame-faced at the hero’s accusation, suggesting that if a hundred percent of the workers are doing a bad job, there’s not much hope of rectifying the situation.

Both films are fascinating because they come so late in the Montage movement, which lasted from 1925 to 1933, and they are particularly valuable because it’s harder to see the films from this late period than those from the 1920s.

Both films have optional English subtitles.

By the way, Edition Filmmuseum also sells Flicker Alley films, and those in Europe and elsewhere might find them easier to order on its website.

You’re gonna need a bigger shelf

There are three notable new releases of French films. Before I get to the two epic, brick-like sets, let me mention the new Eureka! Blu-ray of Jacques Rivette’s Le Pont du Nord (1981) in the “Masters of Cinema” series. Admirably, the film is presented in its original 1.37:1 aspect ratio. The supplements consist mainly of a thick booklet with some new essays, an interview with Rivette, and so on. You can read more about the booklet’s contents and buy the film here. Note that it is coded BD region B.

Now to the bricks.

At long last the French Impressionist director Jean Epstein is well represented on DVD. Although a few of his most famous films have appeared on video from time to time, these eight discs are a cornucopia of his work (plus a 68-minute documentary on his work by James June Schneider). They come from what are probably the best possible prints, since the set is issued by La Cinémathèque Française. Marie Epstein, who had made films herself in the late 1920s and 1930s, worked at the Cinémathèque for decades and helped preserve her brother’s work. A major retrospective of Epstein’s work ran at the Cinémathèque in April and May; the restorations in preparation for the series made possible to this DVD set. (This page links to further resources on Epstein.)

Epstein started out working for some of the large French film companies, though he mixed somewhat experimental films with more standard ones. His second surviving feature film, Cœur fidèle, is one of his most famous, and perhaps his masterpiece. A beautiful print of it is already available on a Eureka! DBD/BD combo (BD region B). There’s also a French DVD. I wrote a little about it when it made our top-ten films of 1923 list.

The big outer box of the set comes with three inner fold-out disc holders that reflect the phases of his career. The first is “Jean Epstein chez Albatros.” In 1924 Epstein joined the Russian-emigré company Albatros. Three of the four films he directed there are grouped together: Le Lion des Mogols (1924), starring Ivan Mosjoukine and Nathalie Lissenko; Le double amour (1925); and Les aventures de Robert Macaire (1925). The big gap here, and indeed in the entire set, is the absence of the fourth, L’Affiche (1924), which I think is one of his best. It does survive, so I hope it will eventually appear on disc. Apart from L’Affiche, these are all big-budget productions, and Robert Macaire is a serial running 200 minutes. This set has no overlap with the Albatros set from Flicker Alley that I wrote about last year and indeed is an excellent supplement to it.

Beginning in 1926, having been successful with his big Albatros films, Epstein produced his own work under the name “Les Film Jean Epstein.” Again, there were four films, the surviving three of which are on the discs in the second folder, “Jean Epstein: Première Vague”: Mauprat (1926), La glace à trois faces (1927), and La chute de la maison Usher (1928). (The lost film is Au pays de George Sand, 1926.) La chute de la maison Usher was for a long time the only Epstein film available on 16mm prints, which didn’t really do justice to its eerie German Expressionist-influenced sets.

Gradually, however, the reputation of La glace à trois faces (“The three-sided mirror”) has grown, and it is another highlight of Epstein’s career. It introduced a trope of modernism into the cinema, the notion of using point of view to create ambiguity. The story shows scenes concerning one man as seen through the eyes of his three lovers–each, of course, making him seem a very different person.

The other films deserve discovery as well. Le Lion des Mogols has a clever story (written by Mosjoukine) which starts out in a fictional Tibetan city where the hero, a nobleman (Mosjoukine) incurs the sultan’s wrath and flees. A cut to a ship suddenly reveals that we are in a modern world, and the film becomes a fish-out-of-water story as the hero blunders onto the set of a movie location shoot on deck (above). Intrigued, the female star of the film helps him adjust and brings him in as a leading actor. Thus our hero jumps from one genre, the fantasy Far-Eastern melodrama (familiar from various German films of the time, including the Chinese sequence from Lang’s Der müde Tod) to a modern romance. The film has the advantage of scenes in and around Albatros’s own studio:

Les Film Jean Epstein produced some major work, but it didn’t make money, and in 1928 Epstein changed course, He made 28 more films, up until his death in 1953, most of which are virtually unknown. The exceptions are some films modest, lyrical films he shot in Breton. Seven of these are presented as “Jean Epstein: Poèmes Bretons”: Finis Terrae (1928, Epstein’s last silent film), Mor’vran (1930), Les Berceaux (1931) L’Or des mers (1933), Chanson d’Ar-mor (1935), Le tempestaire (1947), and Les feux de la mer (1948). These range from 6 minutes to 82 minutes long. Most have simple plots and involve the sea.

The set has been put together so that the supplements for each film are on the end of its disc, not lumped together on a separate disc. There is also a 158-page book, not booklet, with program notes and many images: posters, designs, publicity stills, and frames. (It also has the smallest page numbers I have ever seen.) I can find no indication that the set is region-coded, but the Amazon.fr page says it’s PAL region 2. (I cannot find any reference to the set on the Cinémathèque’s own site, so I can’t confirm either way.) It does have optional English subtitles.

Since the beginning of film history, France has produced one of the world’s great national cinemas, and Jacques Tati is one of its greatest directors. On Facebook, Ingrid Hoeben, one of Tati’s devoted fans, runs a page called “I’d like to be part of the Monsieur Hulot universe, if only as a cardboard cut-out”, and I think she speaks for many of us. (She also runs a FB page on PlayTime–as she spells it. Many writers use Playtime, and I prefer Play Time.)

For those who love Tati, there is finally a new set of his complete works, restored and available in separate DVD and Blu-ray sets. The imposing big black box contains seven discs, each in its own cardboard fold-over holder, one for each of the features and one for the shorts. There are extras on each disc. The small book included with the set has a brief bio of Tati, information on the restoration of the films, and program notes.

There are various versions of some Tati films. The Mon Oncle disc includes both the French and English-dubbed versions. The Les Vacances de Monsieur Hulot disc has the 1953 version and the 1978 restoration. Jour de fête, which Tati tried to make in color, has three versions: the 1949 release print, the 1964 one with selective color added, and the 1994 restoration of the color version Tati had had to abandon.

The print of Play Time, though visually beautiful, is altered by some tampering by the restorers. It originally contained passages of music over a dark screen at beginning and end. I described these moments in my essay, “Play Time: Comedy on the Edge of Perception” (published in 1988 in Breaking the Glass Armor: Neoformalist Film Analysis). Of the beginning I wrote:

The film begins with pre-credits music involving percussion; at a seemingly arbitrary point in this music, the bright credits shot of clouds fades suddenly in from the darkness. Already we encounter the sound track as a separate level from the image track–as something to which we should pay cloe attention in its own right. (Unfortunately, most of this music seems to have been edited out of the re-release print.) (p. 253)

(The darkness and music actually last about 10 seconds before the cloud shot.)

And the ending, which in the original has several minutes of music played over a black screen:

Play Time structures even our transference, at the end, of aesthetic perception to everyday existence, by continuing its theme music for several minutes after the images stop–so long that we are forced to get up and move about to this music. The film’s sound track becomes an accompaniment for our own actions, inviting us to perceive our surroundings as we have perceived the film. (p. 261)

(The actual timing is about one minute, though it seems longer when you’re sitting in a darkened theater and are used to leaving immediately at film’s end.)

This new disc includes the dark footage at the end and the music, but the credits for the restoration and video are superimposed throughout–quite a different experience than music accompanying darkness. The music over darkness is shortened at the beginning to about 3 seconds, with the logo of Les Films de Mon Oncle’s logo and a dedication to Sophie Tatischeff, Tati’s daughter.

All these superimposed credits alters Tati’s intentions considerably. He clearly meant for that concluding music to make us almost actors in his film and to carry over its defamiliarization of the fictional world into the real world. Without it, this cannot be considered the definitive version of Play Time. It may seem a small matter, but the original decision was completely reflected Tati’s distinctive style.

Fortunately the Criterion collection’s version retains the music over black at the end, as well as a different set of supplements. Completists will need to have both.

For many, Tati’s last feature, Parade, will be new. It’s not a M. Hulot film or even really a fiction film. It was made in Sweden and consists of a variety performance by musicians, singers, a magician, and so on, all MCed by Tati in propria persona. Between other acts, Tati performs some of his most famous pantomime bits, including a remarkable scene where, as a tennis player, he mimes part of the action as if caught by a slow-motion news camera. Tati also devised some little scenes to take place among the audience, which contains some of the same sort of cardboard cut-outs that first appeared in Play Time:

Parade was shot on video during live performances, but the acts were also staged in a studio in 35mm (see bottom). That’s the source of the inconsistent visual style, though it’s less apparent on video than when projected in 35mm on a large screen.

It’s a strange but enjoyable and even complex film, if one goes into it without expecting it to be like Tati’s others.

Very few will have seen all of Tati’s shorts. These fall into three periods.

Three of them are from the mid-1930s, brief comedies ranging from 16 to 24 minutes: On demande une brute, Gai Dimanche, and Soigne ton gauche. Tati was a young music-hall performer at the time, specializing in sports pantomimes.

Second, there is L’École des facteurs (1946), a 16-minute version of of the same story that he expanded into Jour de fête a few years later. L’École des facteurs was his directorial debut, the earlier shorts having been directed by others.

And third, Tati made some shorts late in his career: Cours du soir (directed by Nicolas Ribowski), Degustation maison, and Forza Bastia (the latter two directed by Tati’s daughter, Sophie Tatischeff, who used the original family name).

The set has optional English subtitles and is BD Region B.

On early Soviet cinema and much more

The title of Natascha Drubek’s new book, Russisches Licht: Von der Ikone zum frühen Sowjetischen Kino might seem to imply a narrow field of study. Actually, though, it ranges far, examining the introduction of electric lighting into Russia and examining what a wide range of Russian commentators wrote about light at the time. This includes, of course, the cinema, an art form both composed of light and using light during the filming.

The introductory section covers theoretical approaches to cinema, including the work of the Russian Formalists. Drubek goes on to consider factors in the early history of media in Russian and Soviet cinema, including writings on theaters and film censorship.

She then goes back to the roots of thought on light and media further back in Russian history, dealing with icons and the church, as well as the influence of icons on the Russian avant-garde of the pre-Revolutionary period. Finally she deals with cinema and in particular with the films of Evgenii Bauer.

I cannot claim to have read the book, for with my shaky knowledge of German it would be slow going. But it is an impressive achievement, and anyone interested in Russian/Soviet cinema and especially Bauer should have it. It is available online directly from the publisher.

Tati’s classic fishing routine in Parade.

More cinema Bolognese

Josette Andriot, decked out for Protéa.

Kristin here, with more from Cinema Ritrovato in Bologna:

When one thinks of female masters of disguise and action in the silent cinema, Musidora as Irma Vep in Feuillade’s Les Vampyrs probably springs first to mind. But for the historian, hovering always in the background was the legendary film by Victorin-Hippolyte Jasset, Protéa (1913), with Josette Andriot in the lead role. We knew the film mainly from a frequently reproduced image of the heroine in a black outfit, one of many she wears in the film.

Andriot was unconventionally beautiful, with dark hair and eyes and strong rather than delicate features. She was a genuine athlete, hired initially by Jasset for her riding ability, though he later exploited her acrobatic abilities in chases and scrambles around buildings.

Andriot was unconventionally beautiful, with dark hair and eyes and strong rather than delicate features. She was a genuine athlete, hired initially by Jasset for her riding ability, though he later exploited her acrobatic abilities in chases and scrambles around buildings.

Protéa has now been restored, though there is still missing footage. The heroine’s partner is Lucien Bataille, looking rather like a particularly devious James Cagney in the role of L’Anguille (“The Eel”), whose quick-change abilities and athleticism match hers. The thin, episodic plot revolves around a classic Macguffin, a treaty between two imaginary, vaguely Eastern European countries. The pair must acquire the document and hold onto it through one danger after another, outnumbered and chased all the while by a ruthless gang of spies for the other side.

I was startled by how modern the film seemed. Critics today tend to claim, inaccurately, that big action films throw some big thrill at the audience every few minutes. Protéa really does. The underlying purpose of the plot is to have the two leads escape from one sticky situation and change disguises, only to land immediately in another sticky situation. It’s essentially a serial boiled down into a feature.

The term “cinema of attractions” was originally coined by Tom Gunning to describe very early films that depended on novelties rather than narratives. These days, many academics apply the phrase to almost any film, old or new, boasting a lot of action and big special effects. But I’m tempted to use it of Protéa anyway. Jasset usually doesn’t keep Protéa and L’Anguille in any one disguise or situation long enough to exploit the initial premise. One moment she’s pretending to be a man; next thing we know, she’s an elegant partygoer and L’Anguille is a servant. The basic problem is that whenever the characters get into trouble, they don’t rise to the occasion by exploiting their current roles more cleverly. They just flee and assume a new disguise to try again. As a result most of the individual episodes remain unmemorable.

One exception is a sustained sequence showing the couple as traveling animal trainers. At one point they crawl into the cage and play with a real lion, and they stay in these disguises long enough to actually use the big cats to fend off their pursuers. The final hectic chase, with Protéa on a bicycle fleeing toward a bridge set aflame by the villains, is the most impressive passage we can enjoy as sustained action. (I won’t reveal how it comes out, except to say that the climactic moment prefigures a modern action heroine driving a bus toward a gap in an unfinished freeway.)

Protéa is fun, in large part due to the talent of the two leads. It’s a pity that this was Jasset’s penultimate film. He died in hospital before it was released. (His last film, La Danseuse de Kali, also starring Andriot, was recently rediscovered by our friend Hiroshi Komatsu and was shown in this year’s festival.) Perhaps Jasset would have developed into one of the major directors of serials. Still, one can see why Feuillade, who knew how to build suspense by stretching out a scene’s action, became the French master of the form.

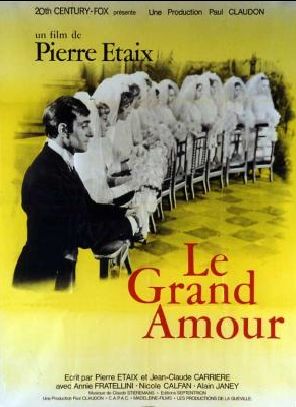

Etaix Refurbished

In an earlier entry, I mentioned that for some years French comic director and actor Pierre Etaix had not controlled the rights to his own films (two shorts and six fiction features). During that time, they were out of circulation and unavailable in any format. That situation has finally been rectified. Etaix has recovered the rights, and all the films have now been restored. They were re-premiered earlier this year at Cannes, and two were included in Il Cinema Ritrovato: the short Heureux anniversaire (1962) and the feature Le grand amour (1969).

Etaix’s early work in the cinema was during the 1950s as an assistant to Jacques Tati, and he is widely seen as having been greatly influenced by Tati. That’s true to some degree. In Le grand amour there are gags using sudden peculiar noises. Although the plot centers around the hero Pierre, his wife Florence, and his in-laws, there are nosy neighbors and waiters through whose eyes we are occasionally asked to view the action. When Pierre’s friend gives him instructions on how to behave on an upcoming date with his pretty secretary, bar patrons assume that they’re witnessing two gay men flirting.

Still, Etaix’s general approach is not particularly Tatian. He does not play a continuing character from film to film. In Le grand amour, as the young husband lured into managing his father-in-law’s factory, he dresses in conservative suits and casual wear; no Hush Puppies, striped socks, and too-short raincoat for him. Pierre succeeds in his dull job, unlike Hulot, who makes a mess of things when given a low-level job at his brother-in-law’s factory. The neighbors watch Pierre not because he is eccentric, but because they jump to wrong conclusions about his mundane behavior.

More importantly, though, Le grand amour creates a great deal of its humor with a technique that Tati would never use. He frequently shows hypothetical alternatives to the scene at hand. What if Pierre’s sophisticated friend were married to Florence? We see a scene played out with the friend in his place. There is a dream in which Pierre’s bed drives like a car along a country road, encountering other bed-cars and finally picking up the new secretary, hitchhiking by the road. When Pierre finally dares to take the secretary out to dinner, he launches into a nervous, boring monologue on business prospects, and we see him as she does, successively older and grayer with each reverse shot. When the gossipy neighbors pass along a story about Pierre, we see the successively exaggerated versions played out one by one, from the reality in which he merely tips his hat to a pretty woman he passes in a park through overt flirting to a passionate encounter behind a bush.

Le grand amour is not as funny as Tati’s films, but that probably results from an explicit melancholy that underlies this tale of disillusionment with marriage and final acceptance of the realities of life-long love. At times it reminded me more of the playful moments in Truffaut, especially in Shoot the Piano Player. Whether or not one wants to place Etaix in the New Wave, his play between reality and fantasy would seem to put him in the category of “ludic modernism” that Malcolm Turvey spoke about in his paper at the recent Society for the Cognitive Study of the Moving Image conference.

The restored print was beautiful, with the kinds of bright and pastel colors and high-key lighting that one seldom sees in the drab films of today. Presumably the new copies will show at other festivals and in art-houses with DVD releases to come.

Cinephiles’ corner

Bologna brings out a bevy of critics, historians, programmers, and unabashed film lovers of all stripes. Herewith, a sampling from DB.

Two critics for the ages: Kent Jones of Physical Evidence and the World Cinema Foundation, alongside Joe McBride, author of books on Ford, Capra, Welles, and Spielberg.

Dick Abel and Virginia Wright Wexman, both distinguished scholars, flank a copy of Dick’s book, French Cinema: The First Wave–presumably kept under glass like the rare specimen it is.

Curatorial cuddling: Haden Guest of the Harvard Film Archive, Adrienne Mancia retired from MoMA (and once a UW Badger).

The Cottafavi Cult invictus: Critics and programmers Barbara Wurm, Olaf Möller, and Christoph Uber, always in the front row.

Camille Blot-Wellens, director of Film Collections at the Cinémathèque Française tells Danish historian Casper Tybjerg of her restoration of Albert Capellani’s Chevalier de Maison-Rouge (1914).

Two walking film encyclopedias sitting down: Kevin Brownlow, pioneer British historian, director, and collector, and Lee Tsiantis of Turner Classic Movies.

David Meeker, master of British cinema and jazz on the screen; Matthew Bernstein, author of Walter Wanger, a study of the Leo Frank lynching, and other studies of film history and culture.

Mariann Lewinsky, heroic programmer of the 1910 series and the Capellani retrospective, introduces Nikolaus Wostry, of Filmarchiv Austria.

More to come in at least one more Bologna-based entry!

Now you see it, now you can’t

DB here:

We usually respond to films spontaneously, but afterward we can think about our responses and figure out why we reacted as we did. When we’re fooled by a mystery, for instance, we can re-watch the film and trace exactly how we were misled. Now that Shutter Island is out on DVD, fans will be dissecting its visual gimmicks. Even when a film isn’t a mystery, a lot of critical analysis involves what we might call a rational reconstruction of how the whole shebang works. Novice screenwriters crack open a movie like The Apartment or The Godfather to peer into the fine mesh of plot construction, to tease out all the setups and plants and twists that seem inevitable only after the fact.

This is film research, we might say, at the personal level. Not in the sense of your or my unique identity, but rather at the scale we see the world. We don’t see atoms or gravity. We evolved to sense and think about middle-sized social and physical phenomena, like places and objects and, especially, other humans. We’re aware of the world because we sense ourselves as individual agents, guided by intentions and desires and beliefs. We’re used to talking about films at this level. When we track action and character, note surroundings and time passing, or ask about the purposes of a plot device or theme, we are working at the level of personhood.

But life assigns us to other levels too. There is the subpersonal level. All kinds of things are happening to you now that you can’t be aware of. You can’t watch the cells in your retina detect this sentence, or the neurons in your brain firing to make sense of it, or the flow of signals to your hand urging the mouse to scroll onward. A huge amount of our mental activity takes place behind the scenes that flit through our consciousness. We can’t pay attention to the man behind the curtain—partly because there is nobody there.

There’s also the suprapersonal level, the level of collective behavior patterns. Now we’re talking about people as parts of large-scale forces, like groups and cultures and societies. Historians have traditionally worked at this level. For example, some researchers have traced how film audiences, en masse, have responded to movies.

More strikingly, many scientists now study “self-organization”—the emergence of patterns of order that don’t seem to be willed or intended by individuals or groups. We find impressive instances in nature: fish swim and birds flock in intricate patterns that no one fish or bird could imagine or dictate. Such self-organization is even more striking in human activities like traffic flow or online networks. Is there a sort of “physics of society”? No doubt people have intentions and quirks, but often we can bracket those out and see shapes in the data that no one could have designed. The classic instance is a power law. A remarkable example is Vilfredo Pareto’s discovery that income distribution in any society tends to settle out as 20 percent of the people controlling 80 percent of the wealth. Mark Buchanan sums up the suprapersonal viewpoint this way: “Think patterns, not people.”

We know we can study films at the personal level. How can we study films subpersonally and suprapersonally too?

Reverse-engineering a movie

Mon Oncle.

My answer comes after four days earlier this month at the annual convention of the Society for Cognitive Studies of the Moving Image. We met in Roanoke, Virigina, in a massive nineteenth-century hotel made over into a convention center. You know the place has things under control when every PowerPoint presentation works flawlessly.

What ideas unite the film scholars, psychologists, and philosophers who gathered here? Roughly, the members explore moving-image media through empirical methods. Empirical inquiry can include classic scientific method (hypothesis/ experiment) or methods of aesthetic, historical or quantitative analysis. Typically the goal is not interpretation of a particular film or TV show or videogame but rather understanding of some general aspects of these media. Not explication, we might say, but rather explanation. Further, most members of the Society are interested in ways that film can be illuminated by areas of modern psychological research, such as neuroscience, cognitive science, and evolutionary psychology.

Some of our philosophers would say that they pursue conceptual analysis rather than empirical inquiry. Still, they join our meetings because the sorts of concepts they want to analyze are the ones that the film folk and the psychologists deploy—concepts like artistic intention or the nature of genre. Many of our liveliest sessions have come from disputes between Filmies, Psychos, and Philosophes.

For more on what we do, I’ve offered some background in earlier entries on this site. I previewed the 2008 convention here and here. I previewed the 2009 convention here and here.

Previews, but not followups. The big problem covering these events is that they’re so busy I have no time to blog during them, and by the time they’re over I’m usually en route to Il Cinema Ritrovato in Bologna. So I tended to make those entries introductions to the cognitive perspective, rather than surveys of who said what. This year, because our gathering was earlier than usual, I’m trying to sum up the event reasonably soon after it ended. We had simultaneous sessions, sometimes three at once, so I attended fewer than half of the talks. I’ll try to mention presentations that seem relevant, even if I didn’t hear them. Similarly, I heard some presentations (e.g., Lisa Broad on possible worlds) that were stimulating but don’t quite fit into my thesis here.

There were plenty of talks that developed arguments at the level I called personal. That is, they analyzed how films were designed to achieve certain effects. This calls for “reverse engineering”: starting from plausible viewer responses and then looking for creative choices made by the filmmakers that seemed to fulfill particular functions.

Take as an example Carl Plantinga’s paper on how we strike up moral attitudes toward characters. He was interested in how we achieve what Murray Smith calls “allegiance”—a “pro-attitude” toward certain characters. Is it just a matter of wishing good things for them, or admiring their positive traits? Is it a matter of sympathy for their situation?

Take as an example Carl Plantinga’s paper on how we strike up moral attitudes toward characters. He was interested in how we achieve what Murray Smith calls “allegiance”—a “pro-attitude” toward certain characters. Is it just a matter of wishing good things for them, or admiring their positive traits? Is it a matter of sympathy for their situation?

Carl argued that all these factors play a role, but they aren’t enough to assure our siding with a character. He argues that allegiance also involves moral judgments, or rather moral intuitions. Films exploit two facts about these moral intuitions: they must be summoned up quickly, without much thought, and they are often driven by emotion rather than ideas.

Oddly enough, our moral intuitions are not necessarily driven by moral standards! Carl drew on Anthony Appiah’s analysis of moral judgments as influenced by how a situation is framed, ordered, and primed—basic cognitive cues that influence responses. For example, Legends of the Fall sets up two brothers, one conventionally moral and the other not. Yet it’s the wild, violent Tristan who earns our sympathies, because he displays vitality, youth, beauty, sensitivity, and closeness to nature. The upshot is that we rationalize a moral judgment on non-moral grounds. Carl got several questions about his conception of morality and the possibility that our moral intuitions are tied to things we value, like beauty.

Malcolm Turvey offered a paper on gags in Jacques Tati. Pointing to prior work on how Tati’s gags are integrated into a shot’s composition (scattered so that we may miss them) and linked to one another (through overlap, Kristin has suggested), Malcolm went on to argue that the gags themselves don’t obey the conventions of classic comedy. They exhibit strategies of misinterpretation, blockage, ellipsis, fragmentation, and concealment that are highly original and unusually challenging. Malcolm is working on a book on “ludic modernism,” and he sees Tati as fitting into this tradition.

Malcolm’s precise and persuasive account was framed by a strong attack on the tendency of cognitive film theory to concentrate on ordinary, even undistinguished films and ignore problematic and avant-garde instances. He pointed to passages in Stephen Pinker’s writings that mock experimental art, and he urged cognitive film researchers to “call Pinker out” for his borderline Philistinism. He remarked that psychological researchers could learn as much from Tati’s work as from ordinary films…and maybe discover new things.

A similar sort of rational reconstruction at the level of personal response was found in many other papers I heard. Jason Gendler dissected the misleading narration in The Blue Gardenia. Rory Kelly wondered why viewers tend to forget the water-utility plotline at the start of Chinatown. James Fiumara considered why modern startle effects are comparatively rare in classic horror films. Torben Grodal isolated a group of “disgust-driven phobic films” (Taxi Driver, Blade Runner, Se7en) that sink so deeply into disgust that melancholy drives out empathy. Lennard Hojberg studied circular camera movements that express the dizziness of love as based on embodied vision.

A similar sort of rational reconstruction at the level of personal response was found in many other papers I heard. Jason Gendler dissected the misleading narration in The Blue Gardenia. Rory Kelly wondered why viewers tend to forget the water-utility plotline at the start of Chinatown. James Fiumara considered why modern startle effects are comparatively rare in classic horror films. Torben Grodal isolated a group of “disgust-driven phobic films” (Taxi Driver, Blade Runner, Se7en) that sink so deeply into disgust that melancholy drives out empathy. Lennard Hojberg studied circular camera movements that express the dizziness of love as based on embodied vision.

Some researchers used quantitative procedures to capture a film’s regularities. Monika Suckfuell (right) exposed some very complex patterns in a short film, Father and Daughter. These create a distinct emotional tone through what she calls “distance editing.” The patterns are combinations of thematic units like problem-solving or humor, and the recurring combinations arouse both comprehension and pleasure. In another quantitative study, Tseng Chiaoi and John Bateman sought to tie concrete uses of filmic elements with more abstract aspects of meaning. (Chiaoi and John had done a presentation on film-based discourse semantics at last year’s event.) Concentrating on characters’ action patterns, Chiaoi used computer software to trace their structures in television commercials and the war genre.

Squeezing the stimulus

Bopping after a session: Tseng Chiaoi and Paul Taberham.

The talks I’ve mentioned, along with several others, analyze processes that we can access by re-viewing films, studying their form and materials, and examining the genres and stylistic traditions to which they belong. But other talks concentrated on the subpersonal areas, the parts of our responses that we can’t access so easily.

For instance, how do we mentally stitch together various shots to create a unified space for a scene’s action? Film scholar Todd Berliner and psychologist Dale Cohen presented an account of how we achieve an illusion of spatial continuity. Initially the brain grasps shots as if they were pieces of space selected by the viewer, and then it builds up a model of the whole space—say a porch in front of a house’s front door. When a character moves his arm a certain way toward an offscreen area, our model of porches and doors makes it most probable that he is pressing the doorbell.

For instance, how do we mentally stitch together various shots to create a unified space for a scene’s action? Film scholar Todd Berliner and psychologist Dale Cohen presented an account of how we achieve an illusion of spatial continuity. Initially the brain grasps shots as if they were pieces of space selected by the viewer, and then it builds up a model of the whole space—say a porch in front of a house’s front door. When a character moves his arm a certain way toward an offscreen area, our model of porches and doors makes it most probable that he is pressing the doorbell.

In such ways we run “beyond the information given.” Filmmakers count on our doing that, so they give us feedback (say, the sound of a doorbell, or a shot of a door opening) that confirms our model of the space. Most mainstream films build in such redundancy. But the unity of these spaces is undermined by some contemporary exhibition technology. Todd and Dale suggested that the mental models we build of space exclude the movie theatre, so that surround sound and 3D become problematic.

They also got several good questions. How concretely specified are these model spaces? How do they develop in the course of a scene? Might our perception of continuity come down to a lack of perception of discontinuity—that is, maybe we operate on very simple default assumptions and don’t build up many models of the space.

Todd and Dale’s presentation was in the Helmholtz tradition; they even invoked “unconscious inference” as part of the story. Another tradition, represented by SCSMI founders Joseph and Barbara Anderson, invokes James J. Gibson’s ecological approach to perception, which argues that such modeling and inference-making isn’t really happening. Things are much more direct: Perception is data-driven, and needs top-down correction only in rare cases (like nighttime or fog).

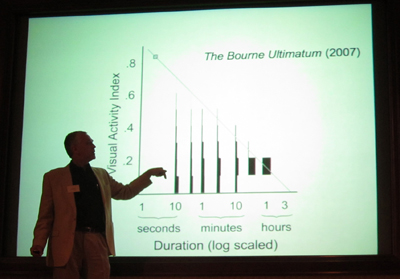

Other perceptual researchers try for a more parsimonious research strategy: How much information about the visual world can we squeeze out of the stimulus? This question was raised by Jordan DeLong, who has been exploring how we can identify emotional arousal through very “low-level” information. Using a corpus of 150 films (more on this later), he looked at shot lengths, the distribution of shot-lengths across a film, and a purely physical measure of visual activity (essentially the change from frame to frame) to see if they correlate with genres we associate with high levels of arousal, like action and adventure films. Jordan’s study is preliminary, but there is the possibility that certain purely physical features are reliable indices to levels of arousal—even if people don’t notice those features and are much more fastened on characters and their actions.

The current projects of Tim Smith’s research team exemplify the parsimonious strategy. Tim is a long-time participant in SCSMI, and his talks show how a research program can expand and enrich itself.

We know people look at certain areas of a shot. We also know that our attention is directed, driven by features of the stimulus. What features? We filmies would pick out shot composition, color, movement, lighting, shot scale, etc. We can access those middle-level variables through expert introspection and analysis. But can those features be further decomposed?

Tim thinks so. We can consider any of these technical qualities as made up of luminance, color channels, and other low-level physical aspects of vision. Through signal-detection methods, Tim seeks to pinpoint what the crucial variables are. The results of his work are soon to be published, and I don’t want to give the game away. I’ll just say that he has shown through eye-tracking that certain low-level features are more important than others in engaging viewers’ attention.

One implication of Tim’s findings is that what I’ve called “intensified continuity” seems to have an optimal grip on spectators. This technique, he remarked, “almost paralyzes the eyes,” yielding “an illusion of active vision with passive eyes.” More generally, his work seems to back up James Cutting’s remark that “There is no such thing as voluntary attention sustained for more than a few seconds at a time.” Most of our attention is at the mercy of the outside world, which means that filmmakers need to engage us at every moment—either with narrative, or with something else we’ll find arresting.

Dan Levin, Pia Tikka; in the background William Brown, Carl Plantinga, and Dirk Eitzen.

Dan Levin gave the keynote address at SCSMI two years ago, and he showed how we vastly overrate our ability to spot outrageous changes in the world or on the movie screen. (He’ll have a field day with the tricks in Shutter Island, such as the one surmounting this blog.) This time around Dan talked about Theory of Mind in the movies, the ways that films exploit our (species-specific?) inclination to attribute beliefs, desires, and goals to the creatures we see in the world, and in films. His paper scanned mandatory, bottom-up cues, middle-level activity (the sort of organization of visual space Todd and Dale discussed), and then “controlled cognition,” such as our narrative expectations. So for Dan it’s not all in the stimulus. Once we’ve picked out certain aspects of it, our Theory of Mind system locks on them.

What aspects? Chiefly, signals of intention and marked eye direction. When we think we’re watching an intentional agent, like a movie character, we tend to see the agent’s eye direction as giving us a clue to his or her aims. Using films he has made, Dan tests people for how eyeline-matched cuts are read, and he varies the cues to see how people construe them differently.

Interestingly, when he showed the same shots in a different order, about two-thirds of the subjects didn’t notice that the order was different. That is, whether the object of the glance or the person glancing came first, gaze deflection remained the primary cue to understanding the situation. This suggests to me that storytelling cinema doesn’t absolutely need the classic pattern of person looking/ person looked at/ person looking, but the extra shot makes sure we all understand (redundancy again).

A similar sort of top-down/ bottom-up theory was proposed by Dan Barratt, who gave it a more computational spin. Like Tim, he works on eye movements; like Todd and Dale he’s interested in how we construct space; like Dan, he seeks out intentional factors. It’s not all in the stimulus, but we won’t know how much until we keep squeezing.

Ripples in the flow of films

The Society broke new ground in what I called the “suprapersonal” realm, that of large-scale patterns of activity that aren’t explicitly coordinated by individuals or groups. Several researchers are probing this in relation to films. Films are, in effect, deposits of human behavior; they are artifacts resulting from choice. What if we find patterns of choice that we can’t plausibly trace to coordinated decision-making?

Chris Atherton raised the issue by considering how to study style statistically. Citing Barry Salt as a pioneer in the area, he focused on the work of the Cinemetrics group and offered suggestions on how to better collect data and track patterns at various levels of generality. More sharply, he posed the question of function. How can you measure that? One implication was that in a big body of films we can disclose order that can’t wholly be explained as the sum of individual choices. Those choices matter, but so do forces we have yet to determine, including historical processes. Chris’s reflections chimed nicely with those of our keynote speaker.

James E. Cutting is a distinguished perceptual psychologist at Cornell. He’s written a fine book on motion perception and has done a quantitative historical study of the creation of the canon of French Impressionist painting. He’s a former dancer and a sensitive appreciator of art and music (and film). He’s the ideal person to analyze ticklish aesthetic issues.

You may have run across him recently because his research on Hollywood films was picked up and trumpeted in the press. “Solved: The Mathematics of the Hollywood Blockbuster,” read one headline. Needless to say, James was doing something more subtle. You can read summaries here and here.

In his lively address, “Attention, Intensity, and the Evolution of Hollywood Film,” James explained two of his areas of interest: the ebb and flow of change across a film, and how that change is tied to human pickup. James studies these topics with a big database: 150 movies from 1935 to 2005. He emphasizes widely seen films belonging to five genres and chosen from the highest-rated titles on IMDB. But there’s a micro- side too. He and his research team went through every film frame by frame coding each one along many dimensions.

Naturally, he takes on the vexed issue of Average Shot Length. You can read the ongoing discussions of this concept on Yuri Tsivian’s Cinemetrics site. What interests James is less ASL in itself than the ways in which comparable patterns of shot lengths cluster in certain parts of the film. A film’s ASL may be 8 seconds, but in some passages several shots might have similar lengths, say 12 seconds each. Moreover, those patterns may “ripple through the film,” recurring at certain intervals and different scales (shot clusters, scenes, or other chunks).

Not every film shows such patterns; film noirs seem random in their patterns of shot lengths. But many movies, especially those of the last fifty years do display these patterns—typically clusters of short shots for physical action, clusters of longer ones for conversations. This clustering tendency is on the increase, even outside the action genre.

Not every film shows such patterns; film noirs seem random in their patterns of shot lengths. But many movies, especially those of the last fifty years do display these patterns—typically clusters of short shots for physical action, clusters of longer ones for conversations. This clustering tendency is on the increase, even outside the action genre.

The finding leads James to ask about the pacing of visual change, which raises the prospect of the sort of tension/ release dynamics we find in music. The patterns he finds don’t look arbitrary because they match the so-called 1/f or pink-noise pattern. This pattern has been detected in the natural world, in heartbeats, and in brain activity. It’s also been discovered in reaction times to tasks. In effect, the 1/f pattern captures not continual attentiveness but rather an alternation of intense concentration, moments of slower pickup, and moments of sheer mind-wandering. A nontechnical explanation of the 1/f pattern is here; a technical one is here.

As for intensity, James is seeking to measure visual activity in the shots. How much change, in effect, can there be from frame to frame? This can be captured by correlating each frame with its mates. James and his team find that from 1930 to 1950, there’s been a steady increase of frame-to-frame visual activity across all genres. The images became busier, with more movement. Today, he suggests, Hollywood is exploring ways to raise the frame-to-frame visual activity—not only through lots of movement of characters (the action film comes to mind) but also through “queasicam” handheld movements.

In combination with decreasing ASLs, Hollywood seems to be asking: How briefly can I show you this and still get the point across? So far, James suggests, films like Mission: Impossible III and The Bourne Ultimatum seem to be the busiest at the visual level. But animated films score about the same.

James has a caveat: The size of the screen matters. Even a big home-theatre screen doesn’t duplicate the breadth of a theatre screen, which activates not only our central vision but our peripheral vision too. That’s why bumpy shots that you can tolerate on a computer monitor may make you queasy at the multiplex. Interestingly, the Bourne films and Cloverfield, James suggests, were more popular on IMDB after the DVD versions came out. Perhaps people were better able to assimilate them on a smaller display.

At one level, James is interested in the subpersonal factors. He grants that you don’t notice cuts but can attend to them if you shift your focus from the story. But the widespread patterns he discloses aren’t easy to ascribe to deliberate planning. Nobody but an avant-gardist would decide to have shots of similar lengths at points 14 minutes or 25 minutes apart throughout the film. But James finds such correlations at levels beyond chance.

I can’t pretend to understand everything mathematical in James’ argument, but I think that his discoveries open up a new way to think about pacing in film. My first impulse is to think about historical causes, as Chris suggests: filmmakers learning from each other, converging on optimum choices. But I also like to entertain the possibility that this optimum carries a resonance even beyond the flux of history. Perhaps like fish and fowl, filmmakers are obeying and viewers are fulfilling, completely unawares, deep rhythms built into nature and numbers.

A tangled databank

Traditional humanists would decry a lot of what goes on at SCSMI meetings. The appeal to general explanations, the recourse to biology and evolution, the use of quantitative and experimental methods would all smack of “scientism.” But more and more, humanists are starting to turn away from the endless reinterpretation of canonical or non-canonical artworks. Many are also quietly defecting from the Big Theory that dominated the 80s and 90s. In film publishing, I’m told, editors have come to an informal moratorium on books on Deleuze. Possibly more people write them than read them.