Archive for the 'Directors: Hitchcock' Category

Recovered, discovered, and restored: DVDs, Blu-rays, and a book

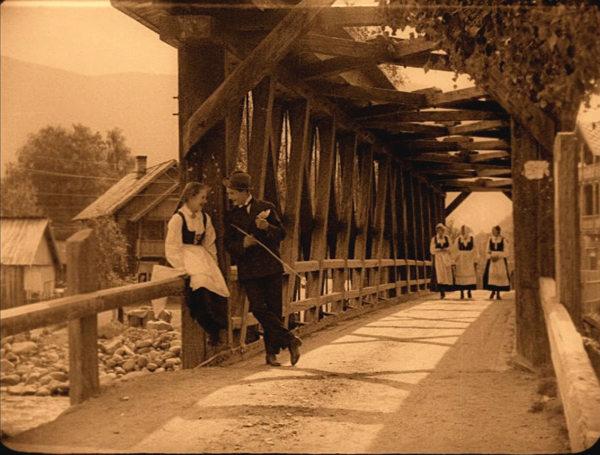

Gipsy Anne (1920).

Kristin here:

A stack of new DVDs/BDs and books has been gradually building up on the floor in a corner of my study. I’ve been meaning to blog about them, but first I had to catch up with viewing and reading. Or did I? With this year’s Il Cinema Ritrovato starting next week, I suddenly realized that the DVDs at the bottom of the pile were ones I bought there last year! Clearly, I would never catch up.

So this entry aims to notify you of releases, many obscure, that you may so far have missed. Mostly the DVDs and BDs come from the dedicated archives and independent home-video companies that release historical rarities and restorations.

Early Scandinavian films

I don’t think I had ever seen a Norwegian silent film, apart from the one Carl Dreyer made there, Glomdalsbruden (The Bride of Glomdal, 1925). Though produced between Master of the House and the wonderful La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc, The Bride of Glomdal is unquestionably one of Dreyer’s lesser works.

In the sales room at last year’s Il Cinema Ritrovato, one stand was selling four new releases of Norwegian and Swedish silent and early sound films. All were issued by the Norsk FilmInstitutt.

Of these, the most important seems to be Fante-Anne (Gipsy Anne), directed in 1920 by Rasmus Breistein. It’s generally considered the first Norwegian feature film, launching the genre of the rural melodrama that would be a mainstay of the industry.

Of these, the most important seems to be Fante-Anne (Gipsy Anne), directed in 1920 by Rasmus Breistein. It’s generally considered the first Norwegian feature film, launching the genre of the rural melodrama that would be a mainstay of the industry.

This is the only one of these Norwegian films that I have so far watched, and it’s a remarkable one. Clearly Breistein and his cinematographer Gunnar Nilsen-Vig were influenced by the great Swedish films of Sjöström and Stiller, and though Gipsy Ann is not up to the best work of those two, it shares the same feeling for landscape for for allowing a melodramatic situation to develop slowly and in unexpected ways.

It tells the story of a foundling child, Anne taken in by a widow who owns a large farm and who raises the girl alongside her son, Haldor. Haldor is a timid boy, constantly led astray by the adventurous Anne. Once they grow up, the two fall in love, but Haldor’s mother pushes her son into an engagement with a young woman from a well-to-do family. In the meantime, Jon, a humble tenant farmer working for the widow, falls in love with Anne, who snubs him.

Gipsy Anne has none of the clumsiness in lighting and staging that one so often sees in European films of the period around 1920. The cinematography is beautiful, as the frame at the top shows. Breistein has mastered shot/reverse shot and other aspects of analytical editing. The lighting is impressive, with some interiors using a strong backlight through windows and a soft fill that gives a sense of realism (left).

The film also sets up neat visual parallels. In a scene in Anne’s childhood (below left), she hides by an old farm building and curiously spies on some local lovers. Much later, she lurks heartbroken by Haldor’s lavish new house as he shows it to his fiancée:

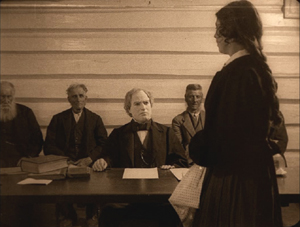

There are even some planimetric shots that yield dramatic compositions, one when Jon comforts the young Anne when she learns that she was adopted, and another, much later, when Anne is in court testifying about the fire that burned down Haldor’s new house:

Again there is a parallel, since Anne is hiding her own guilt in starting the fire, and Jon is about to falsely confess to the crime to protect her. (There’s also a hint at influence from Dreyer in that courtroom shot.)

Of the four releases, Fante-Anne is the only one put out in a Blu-ray version, packaged along with a DVD and an informative booklet in Norwegian and English. The print, with toning and a pleasantly rustic-sounding score, has English subtitles. Oddly enough, the Norsk Filminstitutt does not have an online shop. The film is available from at least two Norwegian online dealers in Scandinavian videos, Nordicdvd and Dvdhuset. It can also be ordered from an American source, Blu-ray.com.

Markens Grøde (The Growth of the Soil) was made only a year later, in 1921; it was directed by Gunnar Sommerfeldt and is another rural melodrama, adapted from a Nobel Prize-winning novel of the same title. This release is 89 minutes long and includes subtitles in English, French, Spanish, German, and Russian. It, too, can be ordered from Nordicdvd and DVDhuset.

The third release is an epic film, Brudeferden i Hardanger (The Bridal Party in Hardanger, 1926). Its two parts run 104 and 74 minutes; it was also directed by Rasmus Breistein, with cinematography by Gunnar Nilsen-Vig. DVDhuset carries it, but not Nordicdvd. It is, however, available from Amazon.uk. It has English subtitles.

Finally there is “Bjørnson på film,” a compilation of three early films based on the pastoral writings of Nobel Prize-winning author Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson and was issued in 2010, the centenary year of the author’s death. Two of these are Swedish productions: Synnøve Solbakken (1919, director John W. Brunius) and Et Farlig Frieri (A Dangerous Proposal, 1919, director Rune Carlsten). Lars Hansen stars in both, and Karin Molander co-stars in Synnøve Solbakken. The third is an early Norwegian talkie, En Glad Gutt (A Happy Boy, 1932, director John W. Brunius).

After considerable searching, I can find no online source for this 2-DVD set. Perhaps it will become available. Otherwise you’ll have to come to Il Cinema Ritrovato and see if it’s on sale again. If not, at least you will have a great time!

All these releases are PAL, though Fante-Anne is also Blu-ray region B; they would all need to be played on a multi-standard machine.

(Mostly) American treasures

The well-known and invaluable “Treasures” series from the National Film Preservation Foundation has become somewhat difficult to keep track of. It started with “Treasures from American Film Archives: 50 Preserved Films.” That was followed by “More Treasures from American Film Archives: 1894-1931.” After that volume numbers appeared, and the references to archives were dropped in favor of thematic collections: “Treasures III: Social Issues in American Film 1900-1934” and “American Treasures IV: Avant Garde 1947-1986.” Then Roman numerals disappeared with “Treasures 5: The West 1898-1938.”(The ones linked are still in print.)

Now we have an unnumbered entry, but it’s still part of the series: “Lost & Found: American Treasures from the New Zealand Film Archive.” Most readers will recall that in 2010 it was announced that about 75 films had been found in the New Zealand Film Archive. News coverage mostly centered on John Ford’s 1927 feature Upstream, which had up to that point been lost. That film forms the central attraction for this new release.

It also includes, however, an incomplete print of a distinctly non-American film, The White Shadow (1924). It was directed by Graham Cutts, but it is mainly of interest now as a film on which the young Alfred Hitchcock worked in several capacities. He wrote the script, based on a novel, and was assistant director, editor, and art director. Despite the enthusiastic tone of the program notes in the booklet accompanying this set, there is little detectable of the later Hitch. The story is ludicrously far-fetched, depending on the old good twin/bad twin contrast, with Betty Compson in both roles (above). At various points the twins pretend to be each other, much to the confusion of the bad twin’s fiancé, played by Clive Brook. The convoluted plot becomes even more so when a series of titles tries to convey the action of the missing final three reels.

The film has its moments. Cutts, who was a decent if not outstanding director, manages some lovely compositions, as with the backlighting in the night interior below left. As with many of Hitchcock’s sets for the film, this one is pretty standard-issue. He obviously had some fun with the set for the tavern called The Cat Who Laughs. It looks a bit jumbled, but it’s actually full of little areas that Cutts uses effectively for picking out pieces of action amid the chaos:

So the Treasures series moves on, as does the Foundation. Not all of the discovered prints made it onto the DVD set. Several more have been preserved since and generously made available for free online viewing at the Foundation’s website; more will be added as the restorations are completed.

Blu-ray USA

American classics continue to make their way onto BD.

Flicker Alley has teamed with the Blackhawk Films Collection to release The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1923, director Wallace Worsley). No original 35mm negative or print is known to survive, so this release was mastered from a 16mm tinted copy struck at some point from the original negative. Some restrained digital restoration was done to clean it up a bit. The extras include an essay and audio commentary by Michael F. Blake and a 1915 film, Alas and Alack, with Chaney in his pre-movie star days playing a hunchback.

The film is available at Flicker Alley’s website, where you can also pre-order their three upcoming releases: a set of all Chaplin’s Mutual Comedies (1916-17); the first volume of The Mack Sennett Collection, including 50 films; and We’re in the Movies, which collects some early local films made by itinerant moviemakers, as well as Steve Schaller’s 1983 documentary, When You Wore a Tulip and I Wore a Big Red Rose, about the first film made in Wisconsin. There’s also a documentary about a small local theater in Los Angeles that showed silent films in the sound age.

D. W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation will celebrate its centennial next year, and now it’s also out on Blu-ray, from both Kino Classics in the USA and Eureka! in the UK. Both have the same new restoration from 35mm elements accompanied by the same score. The extras also appear to be identical–most notably seven Biograph shorts by Griffith about the Civil War. The main difference is that Kino throws in David Shepard’s 1993 restoration, with different musical accompaniment and a 24-minute documentary on the making of the film. Again, the Eureka! version is BD region B.

Last month Eureka! also released a BD of Billy Wilder’s Ace in the Hole (1951, BD region B) in their “Masters of Cinema” program. The release also contains a DVD version. You can check it out, along with other recent releases and upcoming ones here.

Edition-Filmmuseum

This German series works with an impressive array of archives, mostly German but also Swiss and Luxembourgian. The titles that result include modern films (Straub and Huillet figure in their catalogue, as does Werner Schroeter), television, experimental cinema (they’ve done several James Benning films), documentaries, and older films. (No Blu-ray as of now. Perhaps too expensive or perhaps just the sort of restraint that dictates the white backgrounds on their covers.)

Recently Edition-Filmmuseum released a set with two films by Gerhard Lamprecht, a little-known and but in the 1920s an important director of socially conscience films set among the working class. The two-disc release includes Menschen untereinander (1926) and Unter der Laterne (1928), each with two musical tracks to choose from. The German intertitles are subtitled in English and French, and the enclosed booklet is likewise trilingual. Like all the DVDs from this company, there is no region coding.

Similarly, another new release is devoted to the early films of Michail Kalatozov, a Georgian director better known for his Soviet films of the 1950s and 1960s (e.g., The Cranes Are Flying and I Am Cuba). One of the films here is Salt for Svanetia (1930), one of those vaguely familiar but rare titles from the history books on Soviet montage cinema. The other is Nail in the Boot (1932).

Salt for Svanetia is indeed a classic that anyone interested in silent cinema and the Soviet Montage movement should see. Set in an extremely isolated, primitive area of the Caucasus, Svanetia obviously needs a dose of Soviet modernizing. The peasants can barely subsist, and a lack of salt makes their cows and goats unable to produce milk. It’s basically an attempt to combine an ethnographic documentary with large doses of Montage-style rapid editing, canted cameras, heroic framings of people against the sky. At one point a man cutting another’s hair is framed against one of the local feudal era towers in a low angle that makes it look like something out of Alexander Nevsky (above). The film is a fascinating peep into a little-known culture.

Kalatozov stages some sketchy scenes using the locals: an avalanche which kills some men, a resulting funeral, a woman giving birth alone in the countryside. There’s no over-arching plot, though, and the director wisely sticks with showing off local customs. Naturally at the end the Soviets are building a long road to reach the area, and there’s a promise of good things to come.

Nail in the Boot is impressive for about two-thirds of its length. It stages some large battle scenes between what I take to by the Red and White Armies during the Civil War. The Whites are attacking an armored train, and a lot of explosions result. The soldiers aboard the train fire machine-guns, and Kalatozov conveys the sound by alternating single-frame shots of the muzzle of the gun with single-frame shots of the man firing it. Sound familiar? It happens two or three more times in the course of this film. Both of these films are definitely part of the Montage movement, but the director has come along so late in it that he seems to feel all the good ideas have been used, and they’re worth using again. So we get another quotation from October in a canted shot of a cannon’s wheel, and Kalatozov even steals the idea of our hero looking and feeling very small and his prosecutor becoming a looming giant, as in Kozintsev and Trauberg’s The Overcoat:

We are some time into the film before we meet the hero, and I was thinking that this might be one of those Montage films with no single central figure. But well into it, the ammunition on the train is running out, and a messenger is sent to run and get help. Much of the film simply shows him running along, becoming increasingly lame as a bullet in his boot digs into his foot. Ultimately he does not reach his goal, though he tries hard. Once he is put on trial for treason, he blames the shoddy workmanship of the cobblers who made his boot badly. This seems a strange anti-climax after the exciting battle scenes earlier on, but the film actually turns out to be about Soviet workers paying attention to what they’re doing and not putting out a bad product. All the workers looking on at the trial look shame-faced at the hero’s accusation, suggesting that if a hundred percent of the workers are doing a bad job, there’s not much hope of rectifying the situation.

Both films are fascinating because they come so late in the Montage movement, which lasted from 1925 to 1933, and they are particularly valuable because it’s harder to see the films from this late period than those from the 1920s.

Both films have optional English subtitles.

By the way, Edition Filmmuseum also sells Flicker Alley films, and those in Europe and elsewhere might find them easier to order on its website.

You’re gonna need a bigger shelf

There are three notable new releases of French films. Before I get to the two epic, brick-like sets, let me mention the new Eureka! Blu-ray of Jacques Rivette’s Le Pont du Nord (1981) in the “Masters of Cinema” series. Admirably, the film is presented in its original 1.37:1 aspect ratio. The supplements consist mainly of a thick booklet with some new essays, an interview with Rivette, and so on. You can read more about the booklet’s contents and buy the film here. Note that it is coded BD region B.

Now to the bricks.

At long last the French Impressionist director Jean Epstein is well represented on DVD. Although a few of his most famous films have appeared on video from time to time, these eight discs are a cornucopia of his work (plus a 68-minute documentary on his work by James June Schneider). They come from what are probably the best possible prints, since the set is issued by La Cinémathèque Française. Marie Epstein, who had made films herself in the late 1920s and 1930s, worked at the Cinémathèque for decades and helped preserve her brother’s work. A major retrospective of Epstein’s work ran at the Cinémathèque in April and May; the restorations in preparation for the series made possible to this DVD set. (This page links to further resources on Epstein.)

Epstein started out working for some of the large French film companies, though he mixed somewhat experimental films with more standard ones. His second surviving feature film, Cœur fidèle, is one of his most famous, and perhaps his masterpiece. A beautiful print of it is already available on a Eureka! DBD/BD combo (BD region B). There’s also a French DVD. I wrote a little about it when it made our top-ten films of 1923 list.

The big outer box of the set comes with three inner fold-out disc holders that reflect the phases of his career. The first is “Jean Epstein chez Albatros.” In 1924 Epstein joined the Russian-emigré company Albatros. Three of the four films he directed there are grouped together: Le Lion des Mogols (1924), starring Ivan Mosjoukine and Nathalie Lissenko; Le double amour (1925); and Les aventures de Robert Macaire (1925). The big gap here, and indeed in the entire set, is the absence of the fourth, L’Affiche (1924), which I think is one of his best. It does survive, so I hope it will eventually appear on disc. Apart from L’Affiche, these are all big-budget productions, and Robert Macaire is a serial running 200 minutes. This set has no overlap with the Albatros set from Flicker Alley that I wrote about last year and indeed is an excellent supplement to it.

Beginning in 1926, having been successful with his big Albatros films, Epstein produced his own work under the name “Les Film Jean Epstein.” Again, there were four films, the surviving three of which are on the discs in the second folder, “Jean Epstein: Première Vague”: Mauprat (1926), La glace à trois faces (1927), and La chute de la maison Usher (1928). (The lost film is Au pays de George Sand, 1926.) La chute de la maison Usher was for a long time the only Epstein film available on 16mm prints, which didn’t really do justice to its eerie German Expressionist-influenced sets.

Gradually, however, the reputation of La glace à trois faces (“The three-sided mirror”) has grown, and it is another highlight of Epstein’s career. It introduced a trope of modernism into the cinema, the notion of using point of view to create ambiguity. The story shows scenes concerning one man as seen through the eyes of his three lovers–each, of course, making him seem a very different person.

The other films deserve discovery as well. Le Lion des Mogols has a clever story (written by Mosjoukine) which starts out in a fictional Tibetan city where the hero, a nobleman (Mosjoukine) incurs the sultan’s wrath and flees. A cut to a ship suddenly reveals that we are in a modern world, and the film becomes a fish-out-of-water story as the hero blunders onto the set of a movie location shoot on deck (above). Intrigued, the female star of the film helps him adjust and brings him in as a leading actor. Thus our hero jumps from one genre, the fantasy Far-Eastern melodrama (familiar from various German films of the time, including the Chinese sequence from Lang’s Der müde Tod) to a modern romance. The film has the advantage of scenes in and around Albatros’s own studio:

Les Film Jean Epstein produced some major work, but it didn’t make money, and in 1928 Epstein changed course, He made 28 more films, up until his death in 1953, most of which are virtually unknown. The exceptions are some films modest, lyrical films he shot in Breton. Seven of these are presented as “Jean Epstein: Poèmes Bretons”: Finis Terrae (1928, Epstein’s last silent film), Mor’vran (1930), Les Berceaux (1931) L’Or des mers (1933), Chanson d’Ar-mor (1935), Le tempestaire (1947), and Les feux de la mer (1948). These range from 6 minutes to 82 minutes long. Most have simple plots and involve the sea.

The set has been put together so that the supplements for each film are on the end of its disc, not lumped together on a separate disc. There is also a 158-page book, not booklet, with program notes and many images: posters, designs, publicity stills, and frames. (It also has the smallest page numbers I have ever seen.) I can find no indication that the set is region-coded, but the Amazon.fr page says it’s PAL region 2. (I cannot find any reference to the set on the Cinémathèque’s own site, so I can’t confirm either way.) It does have optional English subtitles.

Since the beginning of film history, France has produced one of the world’s great national cinemas, and Jacques Tati is one of its greatest directors. On Facebook, Ingrid Hoeben, one of Tati’s devoted fans, runs a page called “I’d like to be part of the Monsieur Hulot universe, if only as a cardboard cut-out”, and I think she speaks for many of us. (She also runs a FB page on PlayTime–as she spells it. Many writers use Playtime, and I prefer Play Time.)

For those who love Tati, there is finally a new set of his complete works, restored and available in separate DVD and Blu-ray sets. The imposing big black box contains seven discs, each in its own cardboard fold-over holder, one for each of the features and one for the shorts. There are extras on each disc. The small book included with the set has a brief bio of Tati, information on the restoration of the films, and program notes.

There are various versions of some Tati films. The Mon Oncle disc includes both the French and English-dubbed versions. The Les Vacances de Monsieur Hulot disc has the 1953 version and the 1978 restoration. Jour de fête, which Tati tried to make in color, has three versions: the 1949 release print, the 1964 one with selective color added, and the 1994 restoration of the color version Tati had had to abandon.

The print of Play Time, though visually beautiful, is altered by some tampering by the restorers. It originally contained passages of music over a dark screen at beginning and end. I described these moments in my essay, “Play Time: Comedy on the Edge of Perception” (published in 1988 in Breaking the Glass Armor: Neoformalist Film Analysis). Of the beginning I wrote:

The film begins with pre-credits music involving percussion; at a seemingly arbitrary point in this music, the bright credits shot of clouds fades suddenly in from the darkness. Already we encounter the sound track as a separate level from the image track–as something to which we should pay cloe attention in its own right. (Unfortunately, most of this music seems to have been edited out of the re-release print.) (p. 253)

(The darkness and music actually last about 10 seconds before the cloud shot.)

And the ending, which in the original has several minutes of music played over a black screen:

Play Time structures even our transference, at the end, of aesthetic perception to everyday existence, by continuing its theme music for several minutes after the images stop–so long that we are forced to get up and move about to this music. The film’s sound track becomes an accompaniment for our own actions, inviting us to perceive our surroundings as we have perceived the film. (p. 261)

(The actual timing is about one minute, though it seems longer when you’re sitting in a darkened theater and are used to leaving immediately at film’s end.)

This new disc includes the dark footage at the end and the music, but the credits for the restoration and video are superimposed throughout–quite a different experience than music accompanying darkness. The music over darkness is shortened at the beginning to about 3 seconds, with the logo of Les Films de Mon Oncle’s logo and a dedication to Sophie Tatischeff, Tati’s daughter.

All these superimposed credits alters Tati’s intentions considerably. He clearly meant for that concluding music to make us almost actors in his film and to carry over its defamiliarization of the fictional world into the real world. Without it, this cannot be considered the definitive version of Play Time. It may seem a small matter, but the original decision was completely reflected Tati’s distinctive style.

Fortunately the Criterion collection’s version retains the music over black at the end, as well as a different set of supplements. Completists will need to have both.

For many, Tati’s last feature, Parade, will be new. It’s not a M. Hulot film or even really a fiction film. It was made in Sweden and consists of a variety performance by musicians, singers, a magician, and so on, all MCed by Tati in propria persona. Between other acts, Tati performs some of his most famous pantomime bits, including a remarkable scene where, as a tennis player, he mimes part of the action as if caught by a slow-motion news camera. Tati also devised some little scenes to take place among the audience, which contains some of the same sort of cardboard cut-outs that first appeared in Play Time:

Parade was shot on video during live performances, but the acts were also staged in a studio in 35mm (see bottom). That’s the source of the inconsistent visual style, though it’s less apparent on video than when projected in 35mm on a large screen.

It’s a strange but enjoyable and even complex film, if one goes into it without expecting it to be like Tati’s others.

Very few will have seen all of Tati’s shorts. These fall into three periods.

Three of them are from the mid-1930s, brief comedies ranging from 16 to 24 minutes: On demande une brute, Gai Dimanche, and Soigne ton gauche. Tati was a young music-hall performer at the time, specializing in sports pantomimes.

Second, there is L’École des facteurs (1946), a 16-minute version of of the same story that he expanded into Jour de fête a few years later. L’École des facteurs was his directorial debut, the earlier shorts having been directed by others.

And third, Tati made some shorts late in his career: Cours du soir (directed by Nicolas Ribowski), Degustation maison, and Forza Bastia (the latter two directed by Tati’s daughter, Sophie Tatischeff, who used the original family name).

The set has optional English subtitles and is BD Region B.

On early Soviet cinema and much more

The title of Natascha Drubek’s new book, Russisches Licht: Von der Ikone zum frühen Sowjetischen Kino might seem to imply a narrow field of study. Actually, though, it ranges far, examining the introduction of electric lighting into Russia and examining what a wide range of Russian commentators wrote about light at the time. This includes, of course, the cinema, an art form both composed of light and using light during the filming.

The introductory section covers theoretical approaches to cinema, including the work of the Russian Formalists. Drubek goes on to consider factors in the early history of media in Russian and Soviet cinema, including writings on theaters and film censorship.

She then goes back to the roots of thought on light and media further back in Russian history, dealing with icons and the church, as well as the influence of icons on the Russian avant-garde of the pre-Revolutionary period. Finally she deals with cinema and in particular with the films of Evgenii Bauer.

I cannot claim to have read the book, for with my shaky knowledge of German it would be slow going. But it is an impressive achievement, and anyone interested in Russian/Soviet cinema and especially Bauer should have it. It is available online directly from the publisher.

Tati’s classic fishing routine in Parade.

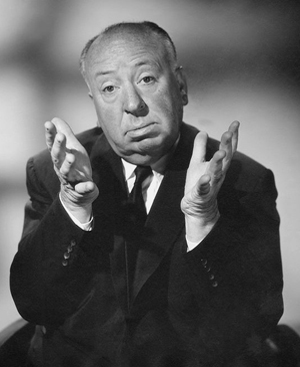

Hitchcock again: 3.9 steps to s-u-s-p-e-n-s-e

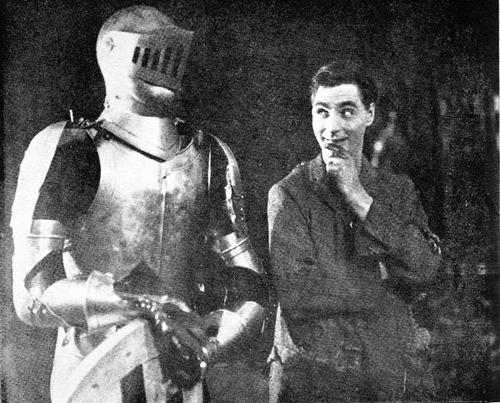

Henry Edwards; Alfred Hitchcock.

DB here:

My previous entry reminded you that Hitchcock was notorious for distinguishing between suspense and surprise. To achieve suspense, he maintained, the audience has to be aware of more than the characters know. Surprise arises when we know as much as the characters, or less. Hitchcock also declared his general preference for suspense, since it provides prolonged tension while surprise produces merely a momentary buzz. The mystery was: Where do this distinction and this preference come from? Are they original with Sir Alfred, or can we find precedents?

The story so far:

Step 1: The distinction itself goes back at least to the eighteenth century and the playwright/theorist Gotthold Ephriam Lessing. Lessing likewise expressed his preference for suspense because it demanded superior craftsmanship and yielded stronger effects on the audience.

Step 2: The distinction and the preference for suspense was still circulating in late nineteenth and early twentieth-century commentaries on theatre. My entry also mentioned a 1922 screen playwriting manual by Howard Dimick that took the same stance.

So we’ve located general conditions for influence. By the early 1920s, the suspense/surprise doublet was still circulating in the worlds of film and theatre, when Hitchcock was starting his career. But influence, like its source-word influenza, requires close contact. It would be good to find the secret agent who might have passed along the idea to the young director.

Step 3: My P.S. to the entry ropes in one candidate: Eliot Stannard. Richard Allen proposed him as a possibility, and Ian Macdonald supplied information that strengthened the suspicion. Stannard was a busy screenwriter of the period, who worked closely with Hitchcock on nearly all his silent pictures, and he even wrote a manual on screenwriting. Although he apparently didn’t talk about suspense and surprise in print, he would have known William Archer and other drama theorists who did. Stannard could well have initiated Hitchcock into the idea.

Step 3.9: But do we have the wrong man? After I posted my P. S., another foreign correspondent weighed in. Charles Barr writes:

A key figure here is Henry Edwards. Director in British cinema 1916-1937, and actor for much longer. His (lost) feature film Lily of the Alley in 1923 made a big point of avoiding intertitles. Whether or not he saw it, Hitchcock must have at least been aware of it, even though later he always said that The Last Laugh was the first such film. And already in 1920 Edwards had spelled out the surprise/suspense distinction: see attachment from the trade paper The Bioscope.

Edwards was indeed a major figure, as producer, actor, and director during the 1910s and 1920s. At the British Film Institute site, Geoff Brown and Briony Dixon provide a lively account of his career. He was clearly in a position to influence younger filmmakers.

The 1920 Bioscope article, cited in the Brown/Dixon overview and supplied to Charles by Ph.D. student Michaela Mikalauski, is a revelation. Edwards writes:

We must so construct our story that suspense is created–suspense is the dread that something may happen, and it is on this that we must build our story.

We must so construct it, that by careful preparation impeding difficulties or dangers are looming up before our characters. We must show the audience these dangers, and keep our characters ignorant of them until the proper moment; and it is the nearing of the danger to the blissfully ignorant character, making us long to cry out and warn him, that give suspense.

Tellingly, Edwards uses an example of an explosion. Imagine that our hero, wandering in the wilderness, has taken shelter in a shack. He sits on a box and lights a cigarette. While he has a leisurely smoke, his match has ignited some dry rubbish by the box. He rises and leaves the shed, just as the box is blown to pieces. Now we realize that it contained dynamite.

Here is a case in which there is expectancy, and never for a moment suspense, because the audience does not know of the impending danger to the character.

Now let us defy the critics who clamour for “surprise” in film construction, and tell the incident in the language of the screen.

Edwards goes on to imagine that we’ve seen quarrymen leave the box of dynamite behind. When the hero ambles in and settles down on the box for a smoke, we’re already apprehensive. Now every gesture he makes prolongs the tension, and we watch anxiously as the discarded match ignites scraps beside the box.

It becomes a question as to which will take the longer, the hero to recover his strength and go, or the box of dynamite to explode. Here is sheer suspense, and when there hero has gone it is no jar to the audience but rather a pleasurable expectancy to see the box explode harmlessly in the air.

After supplying another, more psychological example, Edwards concludes his piece: “The letters of the film alphabet are s-u-s-p-e-n-s-e.”

This article–published the very year that a young and innocent Hitchcock began work for Famous Players-Lasky in Islington–shows that the terms in which Hitchcock understood the suspense/ surprise distinction were already clearly articulated in English film culture. Even the bomb situation that Hitchcock would summon up for Truffaut is there in Edwards’ piece. But of course this information doesn’t sabotage the standing of Stannard, who may have read the Bioscope article and transmitted its lesson to Hitchcock in later years.

I confess I had thought I was done with the thing, but the last few days have brought a small frenzy of emails, and I’m feeling a bit of vertigo. Still, there seems not a shadow of a doubt that Hitchcock was maintaining his faith in a storytelling device that goes back quite far and still had a grip on the formative years of British and American cinema.

Thanks very much to Charles Barr for the information and for sending me the Edwards article. It was published as “The Language of Action,” Bioscope (1 July 1920), supplement p. iv. Thanks also to Michaela Mikalauski for locating the piece, and to Antti Alanen for forwarding some crucial email addresses.

Charles’ revised edition of his Vertigo monograph includes some further comments on the suspense/surprise distinction as it relates to that film. Charles is also completing a new book, with Alain Kerzoncuf, called Hitchcock: Lost and Found. It surveys the little-known films from all periods of Hitchcock’s career. “It devotes some 15,000 words to ‘Before the Pleasure Garden,’ discussing the 21 films Hitchcock was involved with (surviving in whole or part or not at all) and also a bit on the wider context, which is where Edwards comes in. This is all about to go to the publisher (Kentucky) and if all goes well will be out by the end of 2014.”

I’m grateful to all. The little adventure, which I suspect is not quite over, has been rich and strange.

Broken Threads (1918), produced and directed by Henry Edwards, who also starred.

Hitchcock, Lessing, and the bomb under the table

DB here:

Every good cinephile knows Alfred Hitchcock’s famous distinction between suspense and surprise. In articles and interviews from the 1930s on, he explained that situations are more gripping if the audience has more knowledge than the characters do. His classic example, in conversation with Truffaut, was a bomb under a table.

We are now having a very innocent little chat. Let us suppose that there is a bomb underneath this table between us. Nothing happens, and then all of a sudden, “Boom!” There is an explosion. The public is surprised, but priot to this surprise, it has seen an absolutely ordinary scene, of no special consequence. Now, let us take a suspense situation. The bomb is underneath the table and the public knows it, probably because they have seen the anarchist place it there. The public is aware that the bomb is going to explode at one o’clock, and there is a clock in the decor. The public can see that it is a quarter to one. In these conditions this innocuous conversation becomes fascinating because the public is participating in the scene. The audience is longing to warn the characters on the screen: “You shouldn’t be talking about such trivial matters. There’s a bomb beneath you and it’s about to explode!”

In the first case we have given the public fifteen seconds of surprise at the moment of the explosion. In the second case we have provided them with fifteen minutes of suspense.

In Film Art, we invoke Hitchcock’s example to illuminate how narration can be more or less restricted. You can confine the narration to what only a character knows, or you can expand it to give the viewer story information that a character doesn’t have. By widening the audience’s knowledge somewhat, you can build suspense; by confining it, you can make the audience share the character’s surprise.

After Hitchcock came to the United States, he often invoked this distinction in interviews, and it became part of craft lore among writers of screenplays and genre fiction. I trace the idea’s fortunes a little in the online essay, “Murder Culture.” In practice, though, Hitchcock didn’t always follow through. Rebecca (1940) and Suspicion (1941) confine our knowledge very closely to the protagonist’s, without providing that wider perspective he advocates in his remarks to Truffaut. And surprise is central to some Hitchcock works, notably Psycho.

In other films, of course, he did follow his own advice. When Johnny Jones detours to the Tower of London in Foreign Correspondent, we know that the little man steering him there intends to kill him. Shadow of a Doubt lets us see Uncle Charlie in a sinister light before he visits Santa Rosa, and glimpses of his behavior strongly hint that he will menace Young Charlie when she starts to investigate him. And of course The Greatest Film Ever Made (or is it?) tips us off to what’s really going on with Madeleine/ Judy before poor Scottie grasps it.

I’ve wondered: Is this suspense/surprise distinction original with Hitchcock? In the tapes of the original interview with Truffaut, he notes: “You know, there has always been this dispute between suspense and surprise. . . . What I’m saying is not new, I’ve said this many times before.” He then launches into a more expansive account of the bomb-table scenario.

His formulation is ambiguous. Is the distinction “not new” because it’s been around a long while (“always”), or because he’s reiterated it many times? And is his preference for suspense an uncommon opinion? Exact answers may lie in the vast Hitchcock literature, but so far I haven’t found them. Here’s what I came up with.

What enduring disquietude

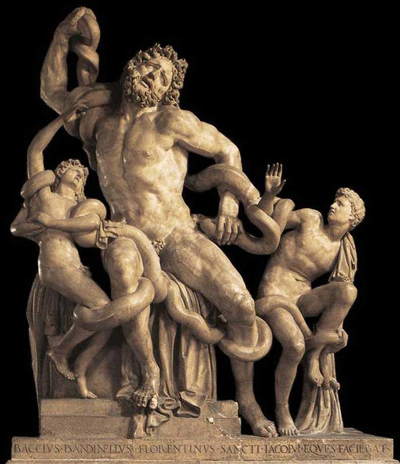

Gotthold Ephriam Lessing was a playwright and drama theorist. His Miss Sarah Sampson (1755) is sometimes considered the first “bourgeois tragedy” in German, and his best-known play is perhaps Nathan the Wise (1779), a classic that was made into a notable silent film. Lessing is also famous for his influential book-length essay Laocoön: An Essay on the Limits of Painting and Poetry (1766), which has been a center of debate in aesthetics ever since.

In that piece he argued for a fundamental distinction between time-based arts (drama, literature) and arts of space (painting, sculpture). From that distinction Lessing inferred a principle of decorum, or expressive fitness, for different media. He claimed that the famous sculpture showing Laocoön and his sons caught in the serpent’s coils could express only a split-second of pain, not the extended agony of their struggle. As a three-dimensional image, the father’s scream is vivid, but it lacks “all the intermediate stages of emotion” that a poem could have rendered as it unfolded in time. The great film theorist Rudolf Arnheim argued that the sound film obliges us to ask whether moving images and recorded dialogue cover different expressive territories, so he called his essay “The New Laocoön.”

Lessing also ruminated on the drama, and his thoughts about playwriting, set down in notes written between 1767 and 1769, contain many intriguing observations. In one passage, he replies to writers who have criticized ancient Greek playwrights for giving away too much in their prologues. These critics have implied that audiences would be more satisfied if big events took them by surprise. So, says Lessing mockingly, let’s simply reedit the plays and chop out all the information that sets up the final reversals.

His serious point is that a surprise yields only a transitory thrill. In the passage below, he uses “poet” and “poem” in a general sense, including storytellers and dramatists, plays and prose fiction.

For one instance where it is useful to conceal from the spectator an important event until it has taken place there are ten and more where interest demands the very contrary. By means of secrecy a poet effects a short surprise, but in what enduring disquietude could he have maintained us if he had made no secret about it! Whoever is struck down in a moment, I can only pity for a moment. But how if I expect the blow, how if I see the storm brewing and threatening for some time about my head or his?. . .

[By not preparing the spectator] the whole poem becomes a collection of little artistic tricks by means of which we effect nothing more than a short surprise. If on the contrary everything that concerns the personages is known, I see in this knowledge the source of the most violent emotions.

Lessing is evidently thinking of classic cases of recognition, plot twists that reveal connections among characters that they were long unaware of. (Oedipus is actually the son of the man he killed!) At another point, Lessing’s English translators find the word Hitchcock uses: “Our participation will be all the more lively and strong the longer and more confidently we have foreseen the issue.” “Foreseeing” here might be too strong, because in Hitchcock’s parable of the bomb we don’t really know the outcome. Will the men at the table escape in time, or halt the bomb, or be blown up? The inevitability of catastrophe that we expect in Greek tragedy produces a different sort of suspense than we experience in modern narratives. Yet it remains suspense nonetheless.

Lessing goes on to suggest that Aristotle valued Euripides most among dramatists not because of the plays’ gruesome endings but at least partly because “the author let the spectators foresee all the misfortunes that were to befall his personages, in order to gain their sympathy.” In other words, we have that sort of unrestricted narration we usually call omniscience. That’s what is at stake in Hitchcock’s bomb example.

Clairvoyant aloofness

It’s a long stretch from the late eighteenth century to Hitchcock’s time. Thanks to Google, and especially its wondrous Ngram software, we can get a rough sense of what happened to the duality of suspense and surprise in those intervening years.

A quick sampling shows that they were conjoined by the late nineteenth century. An anonymous 1884 critic finds that in Tennyson’s plays “the elements of suspense, of surprise, are altogether wanting.” In 1882, J. Brander Matthews, towering authority on theatre history, praises Hugo’s vibrant play Cromwell:

There is the familiar use of moments of surprise and suspense, and of stage-effects appealing to the eye and the ear. In the first act Richard Cromwell drops into the midst of the conspirators against his father,–surprise; he accuses them of treachery in drinking without him,–suspense; suddenly a trumpet sounds, and a crier orders open the doors of the tavern where all are sitting,–suspense again; when the doors are flung wide, we see the populace and a company of soldiers, and the criers on horseback, who reads a proclamation of a general fast, and commands the closing of all taverns,–surprise again. A somewhat similar scene of succeeding suspense and surprise is to be found in the fourth act.

Throughout this period writers fairly often counterpoised suspense and surprise as two essential strategies of plotting. But do the writers recognize the narrational implications they harbor, and do writers display Hitchcock’s preference for suspense? Yes to both.

George Pierce Baker, early twentieth-century drama macher, weighed in with his book Dramatic Technique (1919). He notes that in Shakespeare’s Henry VI, Part I, a revelation of the Countess’s plan yields “a momentary sensation, surprise.” Baker reimagines two versions of the situation: When we know more than one of the antagonists does, and when we know more than both of them do.

Suppose we had been allowed to know the plans of the Countess, and they had seemed very dangerous for Talbot. Then, as she played with him, there would have been more suspense than in Shakespeare’s text, because an audience would have been wondering, not merely “What is the blow Talbot will strike?” but “Can any blow he will strike overcome the seemingly effective plans of the Countess?” Suppose we had been allowed to know the plans of both. Then, as we watched the Countess playing her scheme off against the plan of Talbot, of which she would be unaware, might there not easily be even more suspense? At every turn of their dialogue we should be wondering: “Why does not Talbot strike now? Can he save the situation, if he delays? With all this against him, can he save it in any case?”

Baker concludes that surprise enlivens the situation, but suspense allows for deeper characterization: awaiting an outcome, we must speculate on the characters’ temperaments, motives, and strategies.

Baker has already cited the Lessing passage I’ve mentioned, and he goes on to quote another authority of his period, William Archer. Archer’s Play-Making (1912) became something of a Bible for aspiring playwrights. (Preston Sturges swore by it.) Without explicitly mentioning suspense or surprise, Archer celebrates the pleasures of lording it over the characters.

The essential and abiding pleasure of the theatre lies in foreknowledge. In relation to the characters of the drama, the audience are as gods looking before and after. Sitting in the theatre, we taste, for a moment, the glory of omniscience. With vision unsealed, we watch the gropings of purblind mortals after happiness and smile at their stumblings, their blunders, their futile quests, their misplaced exultations, their groundless panics. To keep a secret from us is to reduce us to their level, and deprive us of our clairvoyant aloofness.

All of these drama theorists are promoting the well-made play as the best model for plot construction. They’re reacting against popular melodrama, with its episodic construction, wild coincidences, and startling twists–a model of what our colleague Lea Jacobs calls “situational” dramaturgy. The preference for suspense is a recognition of the playwright’s adroit shaping of the plot, preparing the later revelations carefully but also creating a steady arc of tension rather than a firecracker string of surprises. Suspense, it’s implied, is just more difficult to achieve than surprise, and a successful passage of suspense testifies to the writer’s skill.

In sum, by the time Hitchcock started his film career, the suspense/surprise couplet was fairly common in discussions of playwriting, and the superiority of suspense was more or less assumed. A 1922 essay concedes, “Whether or not surprise has a legitimate place in the drama is debated by commentators.” But the author, one Delmar Edmundson, suggests that an “entirely unexpected” turn of events in a one-act play can yield a valid thrill, just as in an O. Henry story. Still, the author suggests that even such a twist needs to be subtly prepared for.

In 1922 as well, Howard T. Dimick’s Modern Photoplay Writing: Its Craftsmanship devotes a whole chapter, “Suspense, Excitement, and Crisis,” to the need to make the viewer “participate” in the action. The melodrama Lady X, then recently adapted to film, affords an example. The attorney defending an older woman is in fact her son, though neither of them knows it. (Shades of ancient Greek theatre.) The result is double suspense: we, like the characters, worry about the outcome of the trial, but we also wonder whether they will discover their kinship. “Had the woman’s identity been kept from the spectators till the end and then ‘sprung’ with explosive suddenness, fully half the emotional effect would have been stripped from the play.” Lessing had already anticipated the power of situations of unknown identity: “None of the personages need know each other if only the spectator knows them all.”

At this point, I can’t say precisely how Hitchcock learned of the distinction between suspense and surprise. Clearly, though, the idea was circulating in the theatrical and cinematic milieu of his early career. It’s entirely possible that he read Archer, Dimick, or some comparable source.

In any event, the distinction isn’t original with him. He is, however, the person who made it central to conversations about filmic construction. Recall that he always denied making detective stories. As the Master of Suspense, he wanted to play down the startling solution to a mystery and instead emphasize slowly building tension. And his continuing reliance on the distinction reminds us that the man always in search of what he thought was “purely cinematic” owed a great deal to the theatre. Some critics complained about divulging Judy/ Madeleine’s secret partway through Vertigo, but here, as in most of his films, Hitchcock was adhering to lessons learned from the well-made play. The result was a “disquietude” that endures.

Hitchcock’s remarks appear in Truffaut, Hitchcock, p. 52 of my 1967 edition. There he somewhat qualifies his position about superior knowledge, adding at the end of the passage I’ve quoted: “The conclusion is that whenever possible the public must be informed. Except when the surprise is a twist, that is, when the unexpected ending is itself the highlight of the story.” I take it that this plot construction is different from that of a mystery plot, which poses questions explicitly (whodunit?). A twist ending, by contrast, catches us by surprise because we didn’t suspect that certain aspects of the situation were in question. Central examples would be Stage Fright, Psycho, and, more recently, The Sixth Sense.

Truffaut’s Hitchcock book (the first hardcover film book I ever owned, I think) is a considerable condensation of the extensive interview. The sessions, punctuated by sounds of cigars being lit and snacks being eaten, are preserved on tape. Thanks to the Internets, they are available here. Hitchcock’s slightly more elaborate version of the bomb scenario occurs in session 4, starting at 17:44.

You can read the books I’ve cited in free digital versions: Lessing’s Laocoon and his essays on theatre; J. Brander Matthews’ French Dramatists of the 19th Century; William Archer’s Play-Making; George Pierce Baker’s Dramatic Technique; and Howard T. Dimick’s Modern Photoplay Writing: Its Craftsmanship. Print editions are also available, of course. Other passages I’ve quoted come from Anon., “New Editions of Tennyson,” The Critic and Good Literature (15 March 1884), 123; and Delmar J. Edmundson, “Writing the One-Act Play VIII: Suspense and Preparation,” The Drama 12, 7 (April 1922), 258. Arnheim’s essay “The New Laocoön” is in Film as Art. For more on situational dramaturgy, see Ben Brewster and Lea Jacobs, Theatre to Cinema (Oxford, 1998).

Thanks to Hitchcock adept Sidney Gottlieb for helpful advice on this entry. Anyone interested in Hitchcock needs to consult Sid’s excellent collections Hitchcock on Hitchcock and Alfred Hitchcock Interviews. The suspense/surprise duality recurs throughout them in varied forms.

Google’s Ngram software is here. It’s a tremendously useful tool for historical research.

I’d be grateful to anyone who can help pin down sources for Hitchcock’s acquaintance with the suspense/surprise couplet. As ever, feel free to correspond and I’ll update the entry as necessary.

P.S. 30 November 2013: Correspondence incoming! Richard Allen, NYU professor, lead guitarist, and Hitchcock expert, suggests in an email: “One suspects that the person who probably introduced Hitchcock to this was Eliot Stannard.” Stannard participated in writing all but one of Hitchcock’s all-silent films, and he published a short manual on screenplay technique, Writing Screen Plays (1920), derived from columns he published in Kine Weekly.

I haven’t been able to determine whether Stannard opined on the suspense/surprise duality, as the manual is extraordinarily rare, and the writing on Stannard that I’ve seen doesn’t explore this aspect of his work. Nonetheless I can recommend Charles Barr, English Hitchcock (Cameron & Hollis, 1999), 22-26; Barr’s article, “Writing Screen Plays: Stannard and Hitchcock,” in Young and Innocent? The Cinema in Britain, 1896-1930 (Exeter University Press, 2002), ed. Andrew Higson, 227-241; and especially Ian W. Macdonald’s chapter, “Hitchcock’s Forgotten Screenwriter: Eliot Stannard,” in his brand-new and enlightening Screenwriting Poetics and the Screen Idea (Palgrave Macmillan, 2013), 132-160. Further information on Stannard, or other sources of Hitchcock’s idea, remains welcome.

P.P.S. 2 December 2013: Ian Macdonald writes: “It’s very difficult, as you know, to trace the development of ideas such as the bomb in the briefcase/suspense-surprise thing. Stannard is surprising in that he clearly thought about how best to tell stories on screen, and came close to insights like Russian montage before those ideas became known in London (as Charles Barr has already pointed out). Unfortunately he did not continue to publish ideas after the early 20s, and his work is of course mixed up with ideas from everyone else in his ‘work group’. My picture of Stannard is built up from scraps, and his manual I have only seen in the British Library. This is tantalisingly aimed at the wannabe, so does not take ideas very far either. However, I’m sure he was aware of the prevailing doxa of play construction through such as William Archer, as others (like Brunel) were, and I’m sure that Hitch hoovered up Stannard’s ideas along with everyone else’s. As an inveterate theatre-goer, Hitch would also have been aware of ideas on suspense also. I will also have another look at my material specifically on this suspense question, for further clues, and let you know.” Thanks to Ian, Richard, and Sid Gottlieb for writing! More as things develop.

P.P.S. 5 December 2013: Oh, boy, have things developed. See the next entry.

P.P.P.S. 12 December 20113: Ashish Mehta has found evidence for the suspense-surprise duality in another eighteenth-century figure. He writes:

“Here’s what Samuel Johnson had to say in essay #3 of The Idler, published April 29, 1758, accessible here:

It has long been the complaint of those who frequent the theater, that all the dramatic art has been long exhausted, and that the vicissitudes of fortune, and accidents of life, have been shewn in every possible combination, till the first scene informs us of the last, and the play no sooner opens, than every auditor knows how it will conclude. When a conspiracy is formed in a tragedy, we guess by whom it will be detected ; when a letter is dropt in a comedy, we can tell by whom it will be found. Nothing is now left for the poet but character and sentiment, which are to make their way as they can, without the soft anxiety of suspense, or the enlivening agitation of surprise. (Emphasis added.)”

Thanks to Ashish for this!

Vertigo (1958).

“We didn’t have a sense that VERTIGO was special”: Doc Erickson on classic Hollywood

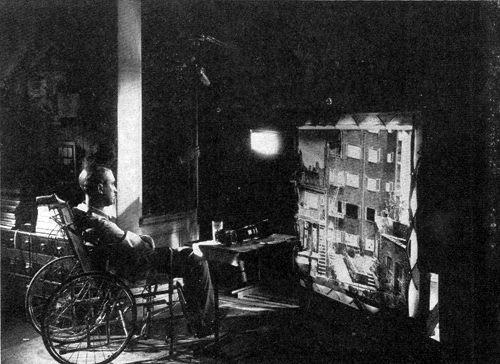

Rear Window (1954); illuminated transparency used to create the lens reflection.

Note: This entry was nearly finished when Roger Ebert died on 4 April. I had intended to send it to him in advance. I think he would want me to post it as I’d planned–just before this year’s Ebertfest.

DB here:

On 17 April, about 1500 people will gather at the Virginia Theatre in Urbana, Illinois, for a celebration of movie love known as Ebertfest. Among Ebertfest’s many guests will be C. O. “Doc” Erickson.

This genial man, who visits Ebertfest each year, is a Hollywood veteran. He was production manager for Alfred Hitchcock, Sidney Lumet, John Huston, Anthony Mann, Roman Polanski, and Ridley Scott. In later years he was associate or executive producer on Chinatown, Urban Cowboy, Popeye, Blade Runner, Looking for Bobby Fischer, Groundhog Day, Kiss the Girls, Windtalkers, and many other projects.

In short, he was an eyewitness to film history. During our visits to Ebertfest Kristin and I have often talked with Doc about his career, and last year I interviewed him for an hour. I thought it was time we set down some of the things we’ve learned. I’ve supplemented Doc’s remarks to us with quotations from Douglas Bell’s 2006 detailed, book-length interview with him.

Setting the scenes

Sunset Boulevard (1950).

Doc began working for Paramount Pictures in December 1944, a year after his graduation from the University of Illinois—Champaign-Urbana. This young man, not yet twenty-one, stepped into the studio that would harbor, across the next few years, The Lost Weekend, The Blue Dahlia, The Strange Love of Martha Ivers, Unconquered, I Walk Alone, A Foreign Affair, Sorry, Wrong Number, The Big Clock, The Heiress, The File on Thelma Jordan, The Furies, Sunset Boulevard, and several Bob Hope, Bing Crosby, and Martin and Lewis comedies.

Initially he worked on estimating the budgets for back-lot and set construction. Doc’s unit would try to give the director some leeway. “Ultimately, it wasn’t [a director’s] fault if the set went over budget. . . . We had to try to get enough money in there so that it wasn’t going to go over budget, because then we’d catch hell.” Then Doc and his colleagues would monitor the building of the set to make sure that the specifications were followed and the budget was adhered to.

Doc moved to stage management and supervision, which required him to plan how a production’s sets were arranged in a sound stage. Four or more sets would have to be fitted together, jigsaw-fashion. Doc would try out arrangements by shifting cutout sets on something like a bulletin board, marked with entrances, walls, and power sources. This was called “spotting the sets.” Spotting was much easier in the days of overhead lighting; lighting from the floor, which became more common as the decade went on, posed extra problems.

Once used, the sets might be dismantled, with different departments rescuing what they could use again. A whole set might be saved for another picture (“fold and hold”). B-pictures recycled sets from A pictures. At the other extreme, ornate interior sets might use units drawn from luxurious houses that had been dismantled. From New York mansions came pieces that were shipped to Hollywood and resassembled to create a salon or ballroom.

Paramount’s back lot included big standing sets, including a train station with some cars on the track. “Then, of course, you had pieces of the train in the scene dock, that could be dragged out and assembled on the stage.” A street at the south end of the lot was used for Westerns and featured a mountain that blocked the view of the adjacent RKO studio.

I’ve long been struck by the fact that articles from the classic period seldom talk about the look of sets for ordinary rooms. So I asked: What colors would be found on the sets in black-and-white movies? Doc smiled. “Black and white—or rather, shades of gray.” Sometimes a bit of green would be added. (I’ve read that sometimes snow was painted yellow to make it dazzle.) Pause and think about how hallucinatory it must have looked: actors moving through a three-dimensional black-and-white movie.

The crew was expected to average fifteen to twenty setups per day, at a period when shooting a top-line feature took anywhere from seven to twelve weeks, or even more. The Paramount policy was to press ahead and finish with a set quickly, even if not every shot was taken. Retakes were likely to be close views of the actors and could be picked up later without need for the full set. This flexibility was feasible because most productions were still shot inside the studio walls. Despite the trend toward location shooting in the late 40s, Doc says, “We weren’t off the lot very much.”

The 1940s saw the rise of the hyphenate filmmaker, and this trend was vigorous at Paramount. The studio roster boasted screenwriter-directors Preston Sturges and Billy Wilder and several director-producers, including Cecil B. DeMille, Mark Sandrich, Mitchell Leisen, and John Farrow. At Paramount, Doc recalls, “The director was king.” No wonder that one of the most kingly figures of the period wound up there for several years.

A step up

The Misfits (1961).

Doc had moved into the role of assistant unit production manager for Secret of the Incas (1954), directed by Jerry Hopper and starring Charlton Heston and Robert Young. His new job involved managing the day-to-day work of filming as a liaison between the production office and the shoot. A production manager works closely with the assistant director to keep the work on schedule and within budget.

When Hitchcock made his five-picture deal with Paramount and was preparing Rear Window, his assistant director, Herbert Coleman, found that all Paramount’s established production managers had been assigned. Coleman asked Doc to take the job, and Hitchcock approved. Doc’s experience with budget estimating and set supervision made him a natural choice for promotion.

Doc supported Hitchcock on several films, becoming a guest at the director’s home and traveling with him. After finishing Vertigo, Hitchcock shifted to studios that had their own personnel for production management. Hitch offered Doc a place on his television series, but Doc moved on to other Paramount pictures: “I wanted to remain in the feature film world.” He worked in Manhattan with Sidney Lumet on That Kind of Woman (1959). Doc admired Lumet’s meticulous planning of every shot, as well as his insistence on table readings of the whole film before shooting.

Doc then teamed up with John Huston. In 1959 Huston was trying to launch The Man Who Would Be King, and for location scouting he took Doc and other team members on a forty-day trip around the world, paid for by Universal. But that project was put on hold. Doc went on to manage production for The Misfits (1961), Freud (1962), and Reflections in a Golden Eye (1967). On the latter two films, Elizabeth Taylor lobbied for Montgomery Clift—winning on Freud, losing on Reflections. (Brando got the part.)

Knowing my interests, Doc pointed out some of Huston’s directorial touches, including some striking uses of deep space. In the image above, Montgomery Clift’s quarrel with the rodeo judge is framed in the car window while Marilyn Monroe frets that he could have died in his fall from the bull. Doc also thinks that Huston showed adroit staging in the Reflections scene showing Brian Keith wiping lipstick off his mouth while Elizabeth Taylor, in the back seat, uses the rearview mirror to help her repaint her lips.

The movie industry was pushing toward ever more spectacular projects, and Doc sometimes went epic. After a production manager on 55 Days at Peking (1963) quit, the film’s editor, Robert Lawrence, suggested Doc. The film’s direction was credited to Nicholas Ray, but the bulk of the footage was shot by Andrew Marton. There followed Doc’s stint on The Fall of the Roman Empire (1964). He recalls Anthony Mann’s excellent eye for composition. The most tangled production was Cleopatra (1963), which had begun shooting in 1960 and was plagued with constant delays. Doc was there for the last eight months of shooting, up to August 1962. He worked under Lewis Merman, the Fox production manager (“one of the greatest human beings I’ve ever known”). Merman was also known as Doc, so the production had both a Big Doc and a Little Doc. It needed even more docs.

Hitch

For my current research I asked Doc a lot about 1940s studio practices, but I couldn’t avoid touching on what everybody asks him about. How was working with Hitchcock? Hitchcock productions have been chronicled in detail by many writers, so I’ll just pick some bits that Doc brought out for me.

On Rear Window (1954), Doc’s expertise in squeezing sets into a sound stage came in handy. The script demanded that the camera be confined to Scottie’s apartment and that we see only what could be seen from that room. Remarkably, Doc recalls no matte shots being used on the production. The apartment, the courtyard outside, and the apartment building opposite were all installed on a single stage.

Doc was struck by the lighting limitations of this complex and confined set. The color film stock was quite slow, and so illumination levels were very high. He told Douglas Bell:

We had to pour so much light into those apartments, up where Raymond Burr was, it almost put him on fire. It was terrible. Or you would never be able to see him, from where we were shooting. . . . But today it would be nothing, it would be a cinch.

Lens length was also a problem because the camera couldn’t easily simulate the telephoto view of the apartment across the courtyard. Doc found a way to mount the camera outside the window to get a little closer to the opposite building and suggest the enlargement provided by Scottie’s long lens.

Hitchcock had claimed he would need only twenty-four days to shoot Rear Window, but it ran to thirty-six, and its cost was considerably beyond what he had estimated. So great was Hitchcock’s standing in the industry that Paramount didn’t object, knowing the result would be a major picture. Doc was on the set every day. Hitchcock would position the actors and frame the shot, but then return to his chair to watch.

Hitchcock liked Doc and picked him again for To Catch a Thief (1955). For this they left the studio and shot on the Riviera for several weeks—Doc’s first location shoot. After the on-site filming was finished, Hitchcock returned to Paramount for studio scenes and Doc stayed to oversee helicopter shots of the roadways with special-effects specialist Wallace Kelly. The team followed the famous Hitchcock lists and storyboards for such second-unit footage.

Without a break Hitchcock drafted Doc for The Trouble with Harry (1956). Originally to be set in England, the story was transposed to New England. Despite some location work, there were a surprising number of studio exteriors (as are quite obvious to our eyes today). Doc supervised the building of woods on Stage 14, but then scattered around leaves brought in from Vermont and New Hampshire.

Doc was involved in scouting locations in Marrakech and London for The Man Who Knew Too Much (1956), along with assisting Coleman and Hitchcock in the usual way. Hitchcock clashed with John Michael Hayes on the project, and according to Doc, Steven Derosa’s account of the contretemps in Writing with Hitchcock does justice to the complexity of the situation.

Doc’s memories of the master’s next production, Vertigo, are detailed, but they and other participants’ accounts are chronicled in Dan Auiler’s Vertigo: The Making of a Hitchcock Classic. What I found surprising were two of Doc’s responses to the project. Doc found that the production went very easily. He thinks that was because he had learned so much about location shooting with the overseas demands of To Catch a Thief and The Man Who Knew Too Much. My second surprise: “We had no sense that Vertigo was special.”

I’m out of step with the world’s critical consensus. I wouldn’t consider Vertigo the best film of all time, or even the best film by Hitchcock. (My votes would go to Shadow of a Doubt, Notorious, Rear Window, and Psycho. All seem to me perfect, endlessly exhilarating pictures.) To a great extent, I think that American Hitchcock never stopped being a 40s director, so I tend to see Vertigo as an uneven mix of plot elements and visual ideas from that wild era. Good as the film is, I think, the expository scenes are rather flatly filmed and lack the flair that Hitchcock brought to such scenes in his earlier films.

But thanks to the undeniable brilliance of many other scenes, along with the revolution of taste promoted by the Cahiers du cinéma critics and the long suppression of the film (making it a sought-after treasure), Vertigo has become a holy grail of obsessional cinema. Its plot premise has fed cinephiles’ fantasies. In the history of taste, a fairly creaky tale of murderous deception has become the ultimate vessel of filmic fascination. One hero’s delusion now epitomizes all movie-made illusion.

Give Doc the last word: “When we finished Vertigo, we never thought of it as being the film that everybody thinks it is today. It’s become bigger than life itself.”

Thanks to Doc Erickson for affable and informative conversations.

Being mostly interested in the Old Hollywood, Kristin and I didn’t question Doc about his work of more recent decades. Those activities are covered in Douglas Bell’s extensive interview, recorded in An Oral History with C. O. Erickson (Los Angeles: Academy of Motion Picture Arts, Margaret Herrick Library, 2006). I’ve drawn much information from this volume. I thank Jenny Romero, Special Collections Department Coordinator at the Herrick Library, for facilitating access to it, and to Kristin for examining it for me during her recent visits to Los Angeles.

For a detailed account of the division of labor on 55 Days at Peking, see Bernard Eisenschitz, Nicholas Ray: An American Journey, trans. Tom Milne (Faber, 1993), 378-389. Andrew Marton, who took over the shoot after Nicholas Ray was dismissed, estimated that sixty to sixty-five percent of the finished film was his work. See Andrew Marton Interviewed by Joanne D’Annunzio: A Directors Guild of America Oral History, 413-418.

Herbert Coleman’s book The Hollywood I Knew: A Memoir: 1916-1988, revisits his AD work with Hitchcock in considerable detail, and many of the anecdotes he recounts involve Doc Erickson. For more on the production of Hitchcock’s films, see Patrick McGilligan’s Alfred Hitchcock: A Life in Darkness and Light and Bill Krohn’s Hitchcock at Work.

Without any planning, the last six months or so have been this blog’s Hitchcock period. The entries include items on Dial M for Murder (screened at the Toronto International Film Festival last September), on David O. Selznick, on the first Man Who Knew Too Much, and on the rise of the suspense thriller during the 1940s. On Lumet, for whom Doc also worked, you can see this entry. The production photographs in today’s entry are taken from Arthur S. Gavin, “Rear Window,” American Cinematographer 35, 2 (February 1954), 76-78.

Kristin and Doc Erickson, Ebertfest 2009.