Archive for the '1940s Hollywood' Category

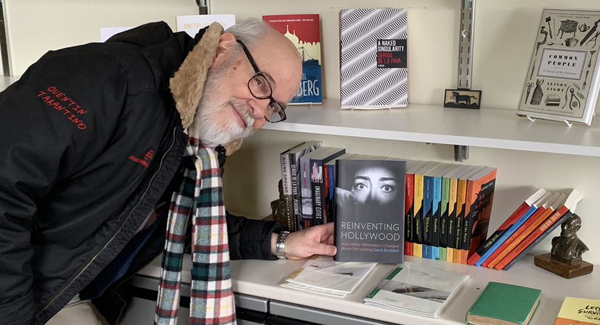

REINVENTING HOLLYWOOD in paperback: Welcome to the Variorum

Happy Death Day (2017).

DB here:

Reinventing Hollywood: How 1940s Filmmakers Changed Movie Storytelling came out about eighteen months ago in hardcover. Amazon and other sellers have been offering it at robust discounts. Now there’s a paperback, priced at $30, though that could also be discounted. I hope all these options put it within the range of readers interested in the period, in Hollywood generally, and in the history of storytelling in commercial cinema.

But of course time doesn’t stand still. Since I turned in the manuscript around Labor Day 2016 I’ve encountered some intriguing things that were more or less relevant to my research questions. (I’ve also found a few errors, most of them corrected in the paperback edition. Meet me in the codicil if you’re curious.) In this blog entry and some followups, I’ll discuss some films, books, and DVD releases that came out after I finished the book. They don’t force me to change my case, I think, but they’re things I wish I could have cited, if only in endnotes.

The first entry in this series is here.

Seeing Happy Death Day 2U reminded me of one of the central arguments of Reinventing. But before I get to that, let me talk about English drama of the years 1660-1710. No, really.

500 plays and more

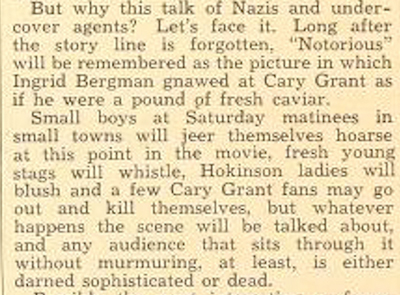

In the late 1960s a young scholar named Robert D. Hume became curious about Restoration drama. Going beyond the canon, he started reading minor works, eventually discovering a collection of microform cards that included virtually all English plays between 1500 and 1800. The set cost about 10% of his pre-tax annual salary, and he struggled to read the bad reproductions of 17th century printing. Still, the effort revealed something important. “All the modern criticism was so radically selective that the critics had no grasp at all of what was really being performed in the theatre.”

In the late 1960s a young scholar named Robert D. Hume became curious about Restoration drama. Going beyond the canon, he started reading minor works, eventually discovering a collection of microform cards that included virtually all English plays between 1500 and 1800. The set cost about 10% of his pre-tax annual salary, and he struggled to read the bad reproductions of 17th century printing. Still, the effort revealed something important. “All the modern criticism was so radically selective that the critics had no grasp at all of what was really being performed in the theatre.”

Hume’s method was simple and drastic. He read all of the preserved plays publicly performed in London between 1660 and 1710. Along with revivals, pageants, translations, and adaptations, there were about five hundred “new” plays, and these he concentrated on. They included famous ones like Marriage à la Mode and The Way of the World, as well as many obscure pieces.

The result was The Development of English Drama in the Late Seventeenth Century (Oxford: The Clarendon Press, 1976). Its first part surveys the conventions and formulas found in subgenres of comic and serious drama (sentimental romance, horror tragedy, and many others). In the second part Rob traces the development of these types across the period.

From the standpoint of my research I was fascinated to see that Rob reveals a teeming set of variations on generic schemas. Characters, situations, and plot twists are mixed and matched. A plot based on romance leading to marriage commonly shows the couple outwitting blocking characters. Sometimes, though, the man must win the woman over. Or she must conquer him. Similarly, when extramarital seduction drives the action, a man may pursue a woman but

occasionally an amorous, often older woman is the pursuer (She wou’d if she cou’d; The Amorous Widow) or an ineffectual male, usually a henpecked husband, is a comic pursuer (Sir Oliver Cockwood in She wou’d).

In Planet Hong Kong I called this tendency of mass entertainment a “variorum” one, by analogy with editions that print all the versions of a major text.

Once a genre gains prominence, a host of possibilities opens up. Horror filmmakers are likely to float the possibility of demonic children, if only because the competition has already shown demonic teenagers, rednecks, cars, and pets. Similarly, once the male-cop genre is going strong, someone is likely to explore the possibility of a tough woman cop.

You might object that using the term “variorum” is just a fancy way to talk about the mechanical formulas of mass entertainment. But by putting the emphasis on variety within familiarity, the label points up the need for constant innovation, great or small. Fans of film genres readily recognize this churn, but what I began to realize is that it’s common as well in both folk narratives and more “industrialized” ones, like theatre and popular literature.

Monuments of scholarship like Hume’s Development remind us that the variorum principle is a primary engine of popular entertainment. The urge for novelty puts pressure on artists to try to fill every niche in the ecosystem, sometimes forcing competitors to strain for far-fetched possibilities. The wild treatment of noir conventions in Serenity is a recent example.

Beyond genre: Style and narrative

Cover Girl (1944).

Some time in the 1990s I began to realize that a lot of my research applies the variorum principle to domains outside genre. For instance, Figures Traced in Light and the last chapter of On the History of Film Style look at cinematic staging from this standpoint, showing how basic principles of staging got realized in many ways across film history. I applied the variorum principle to particular narrative techniques in some essays in Poetics of Cinema, considering the options of forking-path plots and network narratives.

Reinventing tries to trace a wide range of storytelling options as they consolidated in the 1940s. Rob Hume could study every preserved play, but I couldn’t do that for films. I managed to watch about 600. (Later entries in this blog series will mention some I missed.) Not surprisingly, I found the variorum principle at work in the narrative techniques on display.

I set out a couple of prototypes for the most common plots: the single-protagonist one (Five Graves to Cairo) and the plot based on a romantic couple (Cover Girl). Beyond those, I considered less common plot options, such as multiple protagonists and network narratives. Then I went on to consider narrational strategies that cut across all types. What strategies were available for mounting flashbacks, or expressing subjective states? In effect, I tried to reconstruct Forties Hollywood’s storytelling menu, largely independent of genre.

Another way to put this is that I was tracking norms. But the variorum principle shows that a norm isn’t just a mandate: Do this. Any normative practice is a cluster of stronger and weaker options.

These options lead to a cascade of further (normative) choices. Shoot a dialogue scene in a two-shot and you’ll need to adjust performances for viewer pickup. Shoot using a lot of close-ups and you’ll need to cut among your actors more frequently to keep everybody “in the scene”–that is, salient for the audience.

Choose a flashback and you’re forced to decide how far back to start it, what to include that’s relevant to the present action, and how to remind the audience of action that preceded the flashback. Of course you may also choose to try to make viewers forget, because you’ve misled them. That’s what happens in Mildred Pierce and Pulp Fiction.

Usually we find the variorum principle working among several films. What if creators put the principle to work within a single film?

The first day of the rest of your life

Every now and then filmmakers try out forking-path narratives. These plots, I suggest in this essay, trace out alternative futures for their characters. Blind Chance and Run Lola Run are prototypes, though there are plenty of examples earlier and later.

Sometimes the protagonist is dimly aware of the options. The protagonists of Blind Chance and Run Lola run seem to learn from their mistakes in the parallel lines of action. This can yield “multiple draft” narratives in which later story lines show characters struggling to achieve the best revision of circumstances they can.

I’d distinguish plots like these from Groundhog Day, which presents not alternative futures but identical replays of a specific time period. What makes each iteration different is that Phil, realizing he’s living the same day over and over, struggles to behave differently. This pattern has come to be called a time-loop narrative.

The time-loop and forking-path patterns usually provide only changes in the story-world elements of each track. Phil’s changing his routines takes place against a background of recurring situations. Similarly, the protagonist of Source Code gets to try out different ways to stop a train bomber.

What, though, if a looped or forking-path movie tried to survey several alternative genre conventions? That would give us a sense that the variorum idea has been swallowed up within a single film.

This happens, I think, in Happy Death Day. By now it’s not a spoiler to indicate that this slasher movie borrows the Groundhog Day premise and loops a single day in the life of mean girl Tree Gelbman. Each day she’s killed by a stalker in a babyface mask. Each time she dies, she awakes in the bed of Carter Davis, who brought her to his dorm room (without sexytime) to recover from a night of partying. As the days repeat, Tree becomes more desperate to avoid her fate and tries a variety of stratagems. They fail, until they don’t. In the course of them Tree learns to become a nicer person.

What’s interesting to me is that several variorum alternatives of the slasher genre are squeezed into this one film. The stalker kills Tree in a shadowy underpass, in a bedroom during a frat party, in her sorority bedroom, under a friend’s window, on a campus trail, and after chasing her through a hospital, a parking ramp, and a highway. She’s knifed, bludgeoned, hanged, run over, and stabbed with a broken bong.

Of course the shooting-gallery premise of slasher films often generates a string of variations across the film. Boyfriends, girlfriends, figures of authority, and passersby are dispatched by Jason or Freddie Krueger in ever more exotic ways. But in Happy Death Day, the sense of genre replay is heightened by Tree’s being the sole target of the ten variant homicides (one of which is a forced suicide). It’s as if we were watching a performer auditioning for screen tests in which she might be cast as one victim or another. But here the victim is always the Final Girl.

The comedy that haunts many slasher films is enhanced by the preposterous premise that Tree will survive. The deaths become vivid as replays by virtue of their tongue-in-cheek humor, as each slaying tries to outdo the earlier ones and as Tree sarcastically comments on her fate.

With the time-loop convention put into place by Groundhog Day, our interest goes beyond changes in the story world and concentrates more on narrative structure. We watch for scenes we’ve already seen, expecting them to be revised in surprising ways. The handling of the replays foregrounds film technique as well, as when in Happy Death Day Tree’s frantic walk across the quad after a late reset is rendered in distorted imagery reflecting her confusion. We register this as a variant on her earlier stride down the same route–hung-over, but not yet desperate.

One virtue of such repetitions for low-budget cinema is that the variant passages can be shot quite economically. You can save time on location by reusing camera setups, with the actors altering their performance, or their costumes and makeup. In the DVD bonus material, director Christopher Landon talks of following this production strategy. Why does low-budget cinema explore odd narrative options? They can come cheap.

Variants times 2 or 3

Happy Death Day 2U (2019).

A film series often self-consciously varies the story world that the continuing characters confront. In the studio era, Charlie Chan went to the circus and the opera, Mr. Moto got involved in a prizefight scheme, and Ma and Pa Kettle visited Waikiki. Today’s superhero franchises rely on fully-furnished, constantly changing story worlds. Back to the Future, though, launched a series that did more than present a story world that shifted from film to film. The trilogy self-consciously reorganized its plot structure and narration, with replays and alternative outcomes enabled by a time-travel premise. We’re expected to appreciate the altered replays as part of the film’s experience.

The sequel Happy Death Day 2U has just been released in that Dead Zone in which low-end American genre cinema flourishes. I have a lot to say about it, but it’s probably too soon. Still, it’s no spoiler to indicate that it offers a set of variants on the givens of the first film. For one thing, what caused the time loop of the original is now explained. The birthday motif gets elaborated via Tree’s backstory, with strong doses of sentiment. And suspects who were eliminated in the initial film step forward as plausible culprits in this one.

Just as important, there’s an added structural premise that gives the new entry an acknowledged affinity with Back to the Future II and other forking-path tales. To top things off, the second installment supplies a revised version of the outcome of the first one.

Although the sequel isn’t thriving at the box office, perhaps there will be a third entry.

I have the third movie and I have already pitched it to Blumhouse. Everybody is ready to go again if this movie does well. I keep shifting the tone, genre a little bit. The third movie I know is going to be a little different. It’s going to be really bonkers and really fun.

Bonkers or not, having another version would show that the Variorum never sleeps.

Two last points. First, a film I discussed last time, Confession (1937), internalizes the variorum impulse in a milder way, by replaying a key scene from a different character’s viewpoint. More unusually, Confession is a remarkably close remake of a German film, Mazurka, and thus constitutes a homegrown variation on the original.

Secondly, why study the variorum principle? Hume points out:

To insist on analyzing the famous writers and plays in isolation is a mistake: much may be learned by viewing them as they originally appeared–variably successful in the midst of a prolific, unstable, and rapidly changing theatre world.

So one argument is that we can best understand and appreciate masterful filmmaking against the background of normal practice. That seems right to me, but I think there are other good reasons to ask these questions.

For one thing, through bulk viewing of a lot of films, you may discover accomplished works. Many well-regarded films have gained their renown through accidents of release and critical reception. (His Girl Friday is one such.) Good films lurk in many crevices of film history.

I also think that the norms are of interest in themselves. They can show that craft practices harbor more variety than we sometimes think. Studying norms can also reveal offbeat possibilities that are sketched for future development. In Reinventing, I sometimes point to films, either obscure or awkwardly constructed or both, which anticipate trends to come. One example would be the strange, time-shifting exercise Repeat Performance (1947). It’s a Forties counterpart to Dangerous Corner (1934), a two-path plot looking toward more elaborate forking-path storytelling. It shows as well that rather unusual options can float around the edges of the variorum.

My quotations from Rob Hume come from correspondence and The Development of English Drama in the Late Seventeenth Century, pp. ix and 129. Thanks to Rob for sharing the backstory of the book’s composition. Readers interested in his method can learn much more about it in his later study Reconstructing Contexts: The Aims and Principles of Archaeo-Historicism (Oxford, 1999).

This entry relies on a distinction among a film’s story world, its plot structure, and its narration. The idea is explained in this essay and applied to a single film in a blog entry on The Wolf of Wall Street. Plots with loops and forking paths are connected with the idea that “form is the new content” in films from the 1990s and after. I try to chart that ecosystem in The Way Hollywood Tells It: Story and Style in Modern Movies. See also this entry for a quick summary of early examples of multiple-draft plotting. For more on the virtues of Charlie Chan and Mr. Moto, go here.

The following errors in the hardcover version of Reinventing Hollywood are corrected in the paperback.

p. 9: 12 lines from bottom: “had became” should be “had become”. Oops.

p. 93: Last sentence of second full paragraph: “The Killers (1956)” should be “The Killing (1956)”. Arrgh. Elsewhere on this site I discuss Kubrick’s heist film at some length.

p. 169: last two lines of second full paragraph: Weekend at the Waldorf should be Week-End at the Waldorf.

p. 334: first sentence of third full paragraph: “over two hours” should be “about one hundred minutes.” Doggone.

We couldn’t correct this slip, though: p. 524: two endnotes, nos. 30 and 33 citing “New Trend in the Horror Pix” should cite it as “New Trend in Horror Pix.”

Whenever I find goofs like these, I take comfort in this remark by Stephen Sondheim:

Having spent decades of proofing both music and lyrics, I now surrender to the inevitability that no matter how many times you reread what you’ve written, you fail to spot all the typos and oversights.

Sondheim adds, a little snidely, “As do your editors,” but that’s a bridge too far for me. Instead I thank the blameless Rodney Powell, Melinda Kennedy, Kelly Finefrock-Creed, Maggie Hivnor-Labarbera, and Garrett P. Kiely at the University of Chicago Press for all their help in shepherding Reinventing Hollywood into print.

Happy Death Day (2017).

REINVENTING HOLLYWOOD in paperback: Extra-credit reading and viewing

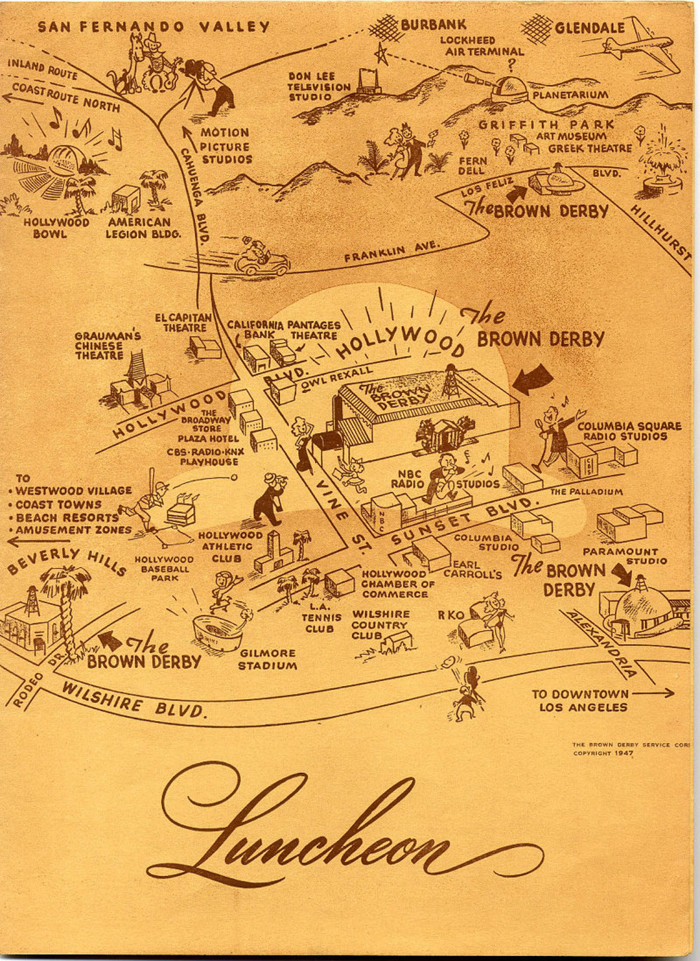

Brown Derby lunch menu.

DB here:

Reinventing Hollywood: How 1940s Filmmakers Changed Movie Storytelling came out about eighteen months ago in hardcover. Amazon and other sellers have been offering it at robust discounts. Now there’s a paperback, priced at $30, though that could also be discounted at some point. I hope these options put it within the range of readers interested in the period, in Hollywood generally, and in the history of storytelling in commercial cinema.

But of course time doesn’t stand still. Since I turned in the manuscript around Labor Day 2016 I’ve encountered some intriguing things that were more or less relevant to my research questions. (I’ve also found a few errors, most of them corrected in the paperback edition. Meet me in the codicil if you’re curious.) In this blog entry and some followups, I’ll discuss some films, books, and DVD releases that came out after I finished the book. They don’t force me to change my case, I think, but they’re things I wish I could have cited, if only in endnotes.

Prosperity helps the movies

Lobby, Loew’s theatre, Rochester, New York, 1940.

Apart from studies of single creators, film historians have often sought to go macro, to tie the films to a broader cultural context. Elsewhere on this site I’ve criticized claims that films directly reflect national character, a zeitgeist, or a mood of the moment. There’s no denying that films bear the traces of the societies that make them. The question is how to understand that process—and how to explain it.

I vote for seeing cultural material as filtered through the constraints and choices of the institutions that filmmakers work in. Writers, directors, producers, and other participants (deliberately or unwittingly) pick out bits of cultural flotsam and reshape them. Buzzy ideas become plot premises. New technologies fulfill old functions. The newspaper-headline montages of the 1930s are replaced by shots of chyrons and cable news feeds today. Stereotypes become characters–sometimes unstereotypical ones. Not reflection, then, but refraction, with agents and social institutions recasting some trends that are out there.

But the macro level shapes cinema in another way: as a set of economic and technological preconditions. Around 1900, a society without a market economy and access to machine technology couldn’t have invented cinema. Before the smartphone, people living in certain countries lacked the infrastructure to access the Internet.

Historians sometimes distinguish between proximate causes—factors we can trace with some specificity—and distal causes, those more basic and pervasive preconditions that provide a background for the proximate causes. Along these lines, I wish I’d drawn on Robert J. Gordon’s 2016 masterwork, The Rise and Fall of American Growth.

Gordon proposes that the century from 1870 to 1970 saw five great clusters of technological innovations: electricity, urban sanitation, chemicals and pharmaceuticals, the internal combustion engine, and modern communication systems. Most became feasible at the end of the nineteenth century, but they took some years to develop, starting to disseminate through the US population from 1920 onward. They peaked, he claims, by 1970 but a significant threshold was crossed around 1940.

Gordon proposes that the century from 1870 to 1970 saw five great clusters of technological innovations: electricity, urban sanitation, chemicals and pharmaceuticals, the internal combustion engine, and modern communication systems. Most became feasible at the end of the nineteenth century, but they took some years to develop, starting to disseminate through the US population from 1920 onward. They peaked, he claims, by 1970 but a significant threshold was crossed around 1940.

Thanks to the Great Depression, FDR’s recovery scheme, and the start of World War II, both the American economy and most American lifestyles improved dramatically. Home electricity, refrigerators, washing machines, radios, telephones, central heating, cheap clothing, sanitation (no more horse droppings on Main Street), the rise of life expectancy, and the fall of infant mortality transformed everyday life. Most of these improvements were tied to the growth of cities. As Gordon puts it:

Except in the rural south, daily life for every American changed beyond recognition between 1870 and 1940. Urbanization brought fundamental change. The percentage of the population living in urban America—that is, towns or cities having more than 2,500 population—grew from 25 percent to 57 percent. By 1940, many fewer Americans were isolated on farms, far from urban civilization, culture, and information.

Reinventing Hollywood emphasized the boom in movie attendance that took off around 1940. Surely American migration to cities fed into this.

The growth of the film industry in the early and mid-Forties parallels a surge in everyday circumstances as well. By 1950, 92 percent of households had a motor vehicle. Penicillin and streptomycin had begun to drastically reduce instances of pneumonia, rheumatic fever, syphilis, and tuberculosis, while a new vaccine eliminated polio. And the rural population continued to dwindle, particularly when people were lured by the fat paychecks in war-related industries.

Did the diffusion of the major consumer technologies through American society directly affect the form and style of the films? No. Just as the struggle with the Axis didn’t demand flashback structure or voice-over narration, neither did the economic forces in society at large. But they did provide a basis for a leisure economy in which filmgoing could flourish, especially when the war cut down rival entertainments and provided more discretionary income. I discuss these processes at some length in Reinventing. Likewise, radio technology didn’t automatically create new narrational devices like voice-over and auditory flashbacks. Radio’s creative artists chose to develop specific techniques to achieve immediate ends. The rise in American standards of living is not a proximate cause but a powerful precondition for the 1940s surge in innovative storytelling. I could have signaled that factor more strongly.

Hanging out

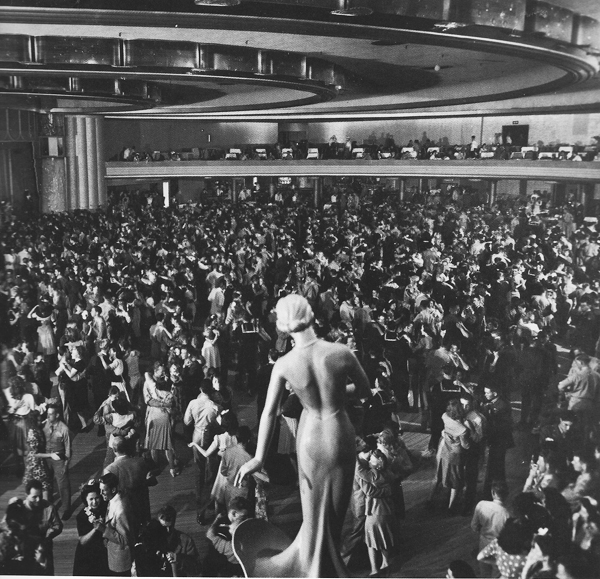

Hollywood Palladium Café.

If the bottom-up approach I tried out is to get anywhere, it needs to show that there’s a community of creators aware of what other folks are doing. Accordingly, the first chapter of Reinventing argues for the importance of Hollywood as bristling with social networks that facilitated cooperation within competition.

Formal organizations, which Kristin, Janet Staiger, and I traced out in our Classical Hollywood Cinema, include professional associations, supply firms, trade papers, and the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. These served as clearing-houses for filmmaking information. Reinventing adds in the more informal ties among personnel on the job or outside work hours (partying, playing cards or polo). In that era of loanouts and independent production, people who socialized might wind up working together.

I mention a few Hollywood hangouts, but now I wish I’d done more with the night spots that sprang up in the 1930s, most notably the Hollywood Derby, the Cocoanut Grove, and the Trocadero.

Most of the watering holes lingered into the Forties, when new attractions like Ciro’s and the Mocambo were added to the list. There were some more risqué ones, like Club Zombie and Florentine Gardens, which advertised topless/ bottomless performers. And there was the vast Palladium café, with a dance floor that could accommodate 7500 people.

These and many more venues are featured in magnificent photos in Jim Heiman’s Out with the Stars: Hollywood Nightlife in the Golden Era. Yes, everybody is shown smoking cigarettes.

I did edge into this area by discussing Breakfast in Hollywood (1946) as a network narrative. It features Bonita Granville, Zasu Pitts, Spike Jones, Nat King Cole, Hedda Hopper, and, I’m told, the mothers of Gary Cooper and Joan Crawford. The movie was a spinoff of a current radio show that broadcast from Sardi’s before moving to a dedicated venue on Vine Street. An enormous sign promised “Glorified Ham and Eggs from Pan to Mouth.”

The minimal switcheroo

Reinventing Hollywood surveys flashbacks, subjectivity, voice-over, ellipsis, multiple-protagonist plots, and other techniques. They were taken up widely and explored in various directions.

But they weren’t brand-new. Apart from voice-over, of course, these storytelling strategies appeared fairly often in the silent era. And although the 1930s largely swerved away from these strategies, they did pop up occasionally. I discussed several examples, such as The Power and the Glory (1933), The Life of Vergie Winters (1934), Peter Ibbetson (1935), and the crazed Poverty Row item The Sin of Nora Moran (1933).

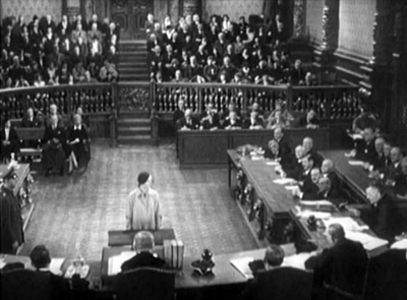

Tom Gunning reminded me of another important precursor. Confession (1937), a Warners melodrama starring Kay Francis, tells of a young woman becoming the prey of a suave but rapacious composer. When she leaves a supper club with him, he’s shot by the woman who has just performed a song. In the singer’s trial, she reveals that he seduced and abandoned her and that the young woman he tried to seduce is her daughter. The court goes fairly easy on her.

The tale is told through some devices that would proliferate in the 1940s. Voice-over monologue to let us in on a character’s thoughts? Check, although it’s very minimal. Flashback to illustrate trial testimony? Check, although that was already a fairly common option from the silent era onward. And a replay of events that show us an event from different viewpoints? Check, although another trial drama, the RKO Ann Harding vehicle The Witness Chair (1936) had pursued the same strategy. (It can be found as far back as The Woman Under Oath (1919), as discussed in an earlier entry.)

What makes Confession more interesting, as Tom also told me, is that it’s a maniacally close remake of Willi Forst’s Mazurka (1935). Here Pola Negri plays the avenging discarded lover. Joe May was a very talented director, but in Confession, he was content to copy the original scene for scene, and sometimes shot for shot. A portion of the German version’s first shot is re-used in the beginning of the American film.

The courtroom is one of several sets that are more or less replicated. Again, the Mazurka shot is first.

Both versions include a replay of an earlier scene. In the first instance, the daughter is unaware that her mother hovers in the hall outside. In the replay, we’re attached to the mother watching the young woman with her adopted mother. The parallel Mazurka sequences are on the top, the Confession ones below.

May’s remake supports a couple of points I made in the book. One source of Hollywood’s 1940s narrative ambitions was foreign cinema. French, German, and British films were exploring these techniques in the 1930s, and some relevant titles got exported to the US. A few were remade, with The Long Night (1947), based on Carné’s Le Jour se lève (1939), being one of the most famous. At the same time, some European directors, like May, started working in Hollywood. Julien Duvivier, for example, leaped into the new US trends with Lydia (1941), Tales of Manhattan (1942), and Flesh and Fantasy (1943).

Hollywood endlessly recycles material, as the new Star Is Born shows. Remakes weren’t as common then as they are now, but they did exist. We might see them as part of the process that includes the switcheroo, the habit of varying an existing premise or gimmick with a change that makes the thing look fresh. I suppose the most famous switcheroo comes in His Girl Friday (1940), where the male protagonist of The Front Page (1931) becomes a woman. Neatly, the name Hildy Johnson works both ways. Even Lydia can be seen as a switcheroo on Duvivier’s own Carnet de bal (1937). Everything, as we know, is grist for the Hollywood mill.

Most broadly, popular entertainment exemplifies what I call the variorum impulse, the urge to tweak or twist existing materials and devices. The aim is to produce something new that’s at once novel and familiar. More on the Variorum in a later entry.

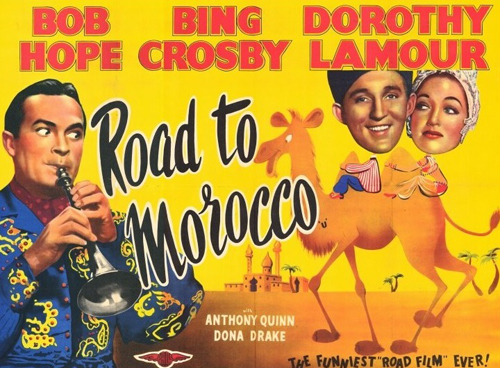

Bing and Bob

I’ve had reason to praise Gary Giddins elsewhere on this site, but I never got around to talking about the wonderful first volume of his biography of Bing Crosby. Now he’s come up with Bing Crosby: Swinging on a Star: The War Years 1940-1946. Of course he deals with the musical career in definitive fashion, but just as important for me is his in-depth coverage of Der Bingle’s movies.

Reinventing, alas, devotes no space to Going My Way (1944), but after reading Giddins’ fifty pages on the film’s production, with sharp excursions into McCarey’s working methods and the tug-of-war about billing in the credits, I wish I had. It’s of course an extraordinary movie, loosely plotted and irresistible in its gentle momentum.

Reinventing, alas, devotes no space to Going My Way (1944), but after reading Giddins’ fifty pages on the film’s production, with sharp excursions into McCarey’s working methods and the tug-of-war about billing in the credits, I wish I had. It’s of course an extraordinary movie, loosely plotted and irresistible in its gentle momentum.

McCarey sold Crosby on the part as if he were peddling a modern High Concept project: “You’re going to play a hep priest.” Giddins carefully traces how the film took the country by storm and led to Crosby’s new, extraordinarily powerful contract with Paramount.

Bing enters my book in Chapter 11, as partner to Bob Hope in the zany Road films. These, along with other Hope vehicles, exemplify for me the acute movie-consciousness we find throughout the 1940s. Of course silent films and early talkies were often set among moviemakers (one of my favorites is Boy Meets Girl, 1938). But the theme shifted into higher gear in the 1940s and early 1950s, when we got films that exhumed Hollywood’s history (The Perils of Pauline, 1947; Singin’ in the Rain, 1952) and comic films that made fun of cinematic conventions. The latter is most wildly illustrated in Hellzapoppin’ (1941), but we get comparable cinematic in-jokes in the Road movies.

Giddins leads us behind the scenes, showing how the Road scripts, tentatively approved by the Breen Office, would get pulled apart during shooting and naughty bits of impromptu got shoved in in.

The writers aimed not only to make scripts funny but also to bamboozle censors. As Bing and Bob crisscrossed the set between takes, like fighters going to their corners, they would receive whispered zingers from personal gagmen, each star looking to unbalance the other; the constant comic rigor roused players and crew. Breen had no knowledge of the ad libs or how scenes would play.

Giddins is constantly throwing crosslights on these films. He shows, for instance, that the “high-velocity raillery” of The Road to Zanzibar (1941) owes something to producer Paul Jones, who had worked on Preston Sturges’ comedies. “The pace of the dialogue between crooner and comedian is impeccable, unforced, and funnier than the actual lines.”

To greater or lesser degree Giddins plumbs all the fourteen films Crosby made in these years, weaving them into the spectacular radio, touring, and recording career of one of the most popular stars in American entertainment. There’s plenty of sadness to go around too.

I could go on and on, as you know. After I finished the book I discovered George S. Kaufman’s 1945 play Hollywood Pinafore; or, The Lad Who Loved a Salary. It uses Arthur Sullivan’s score for H.M.S. Pinafore to mock the movie capital. Here’s a sample featuring the gossip columnist Louhedda:

Somehow all the weekly checks/definitely hinge on sex./ One man fills another’s shoes./Hard to tell whose baby’s whose./ Many autographs annoy/ Ella Raines and Myrna Loy./Goldwyn claims that all our ills/ Can be traced to double bills.

Et cetera. A bit labored, but cute.

Next time: Reinventing Hollywood and Happy Death Day 2U.

Thanks to Tom Gunning, Dan Morgan, Ally Nadia Field, Jim Lastra, Richard Neer, Jim Chandler, Mike Phillips, and Gary Kafer, as well as those who attended my lectures at the University of Chicago in January.

The following errors are in the hardcover version of Reinventing Hollywood but are corrected in the paperback.

p. 9: 12 lines from bottom: “had became” should be “had become”. Yow.

p. 93: Last sentence of second full paragraph: “The Killers (1956)” should be “The Killing (1956)”. What a brain fart. Elsewhere on this site I discuss Kubrick’s heist film at some length.

p. 169: last two lines of second full paragraph: Weekend at the Waldorf should be Week-End at the Waldorf.

p. 334: first sentence of third full paragraph: “over two hours” should be “about one hundred minutes.” Sad!

We couldn’t correct this slip, though: p. 524: two endnotes, nos. 30 and 33 citing “New Trend in the Horror Pix” should cite it as “New Trend in Horror Pix.”

Whenever I find slips like these, I take comfort in this remark by Stephen Sondheim:

Having spent decades of proofing both music and lyrics, I now surrender to the inevitability that no matter how many times you reread what you’ve written, you fail to spot all the typos and oversights.

Sondheim adds, a little snidely, “As do your editors,” but that’s a bridge too far for me. Instead I thank the blameless Rodney Powell, Melinda Kennedy, Kelly Finefrock-Creed, Maggie Hivnor-Labarbera, and Garrett P. Kiely at the University of Chicago Press for all their help in shepherding Reinventing Hollywood into print.

UChi marketing guru Levi Stahl tweets: David Bordwell stops by the office but refuses to pose with his own book unless you also let him include Richard Stark’s Parker novels in the picture. It’s as close as I’ll get to greatness.

NOTORIOUSly yours, from Criterion

DB here:

Notorious was the subject of the first piece of criticism I published. The venue was Film Heritage, one of those little cinephile magazines that flourished, if that’s the word, in the 1960s. My appreciative essay came out in 1969, as I was finishing my senior year in college.

I haven’t dared to look back at it. Actually, I’m not sure I have a copy. The soft-focus imagery of memory tells me that some things that would preoccupy me in the future–interest in narrative structure, style, point-of-view, the spectator’s engagement with mystery and suspense–are there, though in ploddingly naive shape.

Since those days Hitchcock has always been with me. He’s been the subject of articles and blogs and many, many classroom sessions. Now, thanks to the Criterion collection, I’ve had a chance to revisit Notorious.

The new Blu-ray edition includes a dazzling array of extras. Many were available on the now out-of-print 2001 Criterion DVD: two audio commentaries featuring Rudy Behlmer and Marion Keane, the Lux Radio Theatre adaptation starring Joseph Cotten, and newsreel footage of Hitchcock and Bergman. Added to that earlier material are an interview with Donald Spoto, a video essay on technique by John Bailey, a 2009 documentary about the film, a study of the film’s preproduction by Daniel Raim, and a print essay by Angelica Jade Bastien. Since I just got my copy and wanted to tell you about it, I haven’t had time to plunge into all of this, but the samples I’ve checked are exhilarating.

The new Blu-ray edition includes a dazzling array of extras. Many were available on the now out-of-print 2001 Criterion DVD: two audio commentaries featuring Rudy Behlmer and Marion Keane, the Lux Radio Theatre adaptation starring Joseph Cotten, and newsreel footage of Hitchcock and Bergman. Added to that earlier material are an interview with Donald Spoto, a video essay on technique by John Bailey, a 2009 documentary about the film, a study of the film’s preproduction by Daniel Raim, and a print essay by Angelica Jade Bastien. Since I just got my copy and wanted to tell you about it, I haven’t had time to plunge into all of this, but the samples I’ve checked are exhilarating.

Hitchcock is the most teachable of classic directors. His strategies are just obvious enough for beginners to notice them, but they always open up new directions for more experienced viewers.

I reconfirmed all this when I decided to devote a chapter of Reinventing Hollywood to Hitchcock and Welles. These two masters decisively influenced the 1940s, the period I was considering. But they were in turn influenced by the crosscurrents in their filmmaking community. And they came to epitomize, for me, the artistic richness of what Hollywood could do in this golden age.

In addition, I tried to make the case that they carried storytelling strategies typical of the period into later eras. I declared, in a burst of geek recklessness:

Vertigo constitutes a thoroughgoing compilation/revision of 1940s subjective devices. The obsessive optical POV shots of Scottie trailing Madeleine give way to a dream tricked out with pulsating color, abstract rear projetion, stark geometric patterns, and animated flowers. . . . Along with all the other echoes–portraits, therapy for a traumatized man, voice-over confession, point-of-view switches, the hint of a reincarnated or time-traveling woman–the powerful probes of subjectivity make Vertigo, though released in 1958, one of the most typical forties movies.

But then so is Notorious, a film I had little to say about in the book. So I’m glad that Criterion’s invitation to contribute a 30-minute short on this new release led me back to a film I’ve loved for over fifty years.

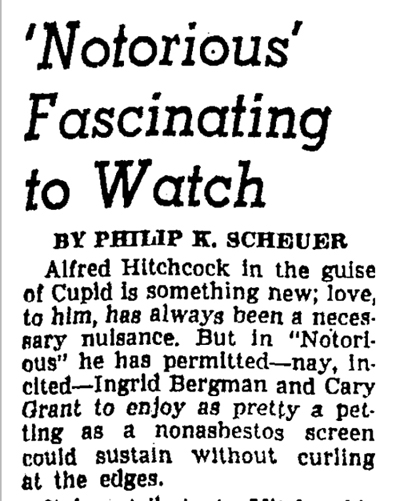

Darned sophisticated, or dead

My supplement concentrates on the climax in Alicia’s bedroom and on the staircase of Sebastian’s mansion. Spiraling out from that sequence, I try to show how it’s the culmination of many storytelling strategies, from point-of-view editing to long takes. I also trace out something I didn’t fully realize until I researched the film’s reception: It was considered very sexy.

For one thing, Ingrid Bergman was associated with innocents, and her playing a promiscuous party girl (“notorious”) was a bit of spice. For another, Hitchcock’s earlier films, though they always had erotic overtones, didn’t really center on a passionate romance. His heroines didn’t convey much smoldering passion, despite all his prattle about glacial blondes thawing out fast. His darkly handsome protagonists (Maxim in Rebecca, Johnnie in Suspicion, Uncle Charlie in Shadow of a Doubt) are more steely than steamy. As for Joel McCrae in Foreign Correspondent and Bob Cummings in Saboteur, they seem virtual Boy Scouts. Only Spellbound, which introduces a psychoanalyst to ecstasy in the rangy form of Gregory Peck, seems a first stab at the sexual complications of Notorious. And the analyst is played, of course, by Bergman, radiant as soon as she takes off her glasses.

The 1940s had a well-established convention that a handsome friend of the family could rescue a wife from the predations of her husband (Gaslight, Sleep My Love) or other tormentor (Shadow of a Doubt). Film scholar Diane Waldman called this figure the helper male. In the second half of Notorious Devlin plays this role. The basic situation–a man stealing another man’s lawfully wedded wife–is pretty edgy in itself, especially since Sebastian is far more frankly in love with Alicia than Devlin is. I try to show that Hitchcock wrings new emotion from the convention by making the husband, trapped between his Nazi gang and his ruthless mother, sympathetic. Meanwhile, the helper male comes off unusually cruel, needling Alicia about the carnal bargain he plunged her into.

And then there’s all that snogging. The romance in Notorious is one long tease–between the characters, and between the screen and the viewer. The Los Angeles Times critic made it the basis of his lead:

Devlin and Alicia are all over each other, notably in the famous scene in her apartment. (Have they done The Deed? Obviously yes.) Their tight embrace, their constant pecking and nibbling and nuzzling as they float across the room, provoked a lot of notice. In the supplement I quote Dorothy Kilgallen, whom my oldest readers will remember from “What’s My Line?” on TV. She wrote this in Modern Screen:

So it makes a certain amount of sense for a power company to assume that incandescent stars can sell electricity, as below. In Toledo, too.

For this and other reasons, I’m happy to have a chance to revisit one of my very favorite Hitchcock films. I bet that you’ll enjoy seeing this stunning copy and immersing yourself in all the bonuses. Hitch is endlessly fascinating, and he’s one of the main reasons we love movies.

Thanks to Curtis Tsui, who produced the disc, as well as Erik Gunneson and James Runde here at UW–Madison, and all the New York postproduction team. Thanks as well to Peter Becker and Kim Hendrickson for all they do to keep Criterion at the top of its game.

Greg Ruth, designer of cover art for Criterion, explains his creative process on their site. More details on the release, with clip, are here.

The Los Angeles Times review comes from the issue of 23 August 1946, p. A7. The Kilgallen Modern Screen piece is available via Lantern, here. If you youngsters didn’t get her reference to Helen Hokinson, go here.

For another in-depth analysis of a single sequence, see Cristina Álvarez López & Adrian Martin’s Filmkrant video essay, “Place and Space in a Scene from Notorious.” They showed me things I had never noticed–more proof of the richness of Hitchcock World.

Cary Grant’s image was used to sell oil a few years before, as illustrated in this entry.

P.S. 21 January 2019: For more on the steamy side of Notorious, there’s “The Clinch That Filled 1,200 Seats,” at the redoubtable Greenbriar Picture Shows. Thanks to John McElwee for bringing it to my notice!

Better Theatres (24 August 1946).

Lovelorn LYDIA: A new installment on the Criterion Channel

DB here:

In the fading days of FilmStruck, Kristin and Jeff and I are looking forward to continuing our Observations on Film Art series on the new version of the Criterion Channel in the spring. (If you’re in the areas served, US and Canada, you can sign up here. I did already. Quick and easy.)

In the meantime, our final entry on the FilmStruck platform is going live on Monday, 19 November. There I consider Julien Duvivier’s Lydia (1941) as an example of the power of flashback storytelling.

I talked about the film in Reinventing Hollywood as part of the massive 1940s revival of this technique. Critics’ long-standing emphasis on film noir has led us to think that that trend epitomized flashback construction, but actually the technique is almost completely general. In the book, I consider several “women’s pictures” that employ it: Kitty Foyle (1940), The Affairs of Susan (1945), The Locket (1946; also discussed here), and Lydia. The Criterion series allows me to illustrate more concretely how Duvivier and his colleagues tell the story of a woman captured by passion and moving into old age almost (but not completely) disillusioned.

Working on the book and the entry made me better appreciate a director I’d neglected. Like everybody else, I had had a high regard for La Belle Équipe (1936) and Pépé le Moko (1937), and I had seen and liked his Simenon adaptation Panique (1946). A special favorite of mine is his cross-border comedy about switchboard romances, Allo Berlin? Ici Paris! with clever sound work quite advanced for 1931. Beyond Lydia, other Hollywood efforts of his proved important for Reinventing Hollywood. Tales of Manhattan (1942) and Flesh and Fantasy (1943) are adroit instances of the episode film, that format using what I called “block construction.”

Duvivier was sometimes disdained by the younger generation as an old-guard academic, but I’ve come to see him as a rather interesting experimentalist. He tried out a day-in-the-life network narrative (Sous le ciel de Paris, 1951), a charming what-if comedy about screenwriting (La Fête à Henriette, 1952), and a solid Gabin polar (Voici les temps des assassins, 1954). His suspense drama Marie-Octobre (1959), might seem overly theatrical because it has a Rope-like confinement to a single evening, an anniversary dinner for survivors of the Resistance, but it’s actually based on a novel and gains tension from its almost real-time duration. It showcases a range of major stars (Darrieux, Blier, Reggiani, Ventura) and boasts one of the most dazzling parlor sets I’ve seen in a long while.

Among his thrillers adapted from English authors there’s the curious Chabrolian exercise, La Chambre ardente (1962), based on a John Dickson Carr novel, and the seedy Chair de poule (aka Highway Pickup, 1963, below) from James Hadley Chase.

I’m sure there are clunkers and potboilers among his dozens of titles, but it’s a pretty distinguished career, running back to the silent cinema and his early classic Poil de carotte (1925). His department-store drama, Au Bonheur des Dames (1930), exemplifies bravura silent-film style at its height. He even remade The Golem (1936).

For me, Lydia encapsulates the ambitions typical of Duvivier and 1940s Hollywood. The film could count as a rewrite of Carnet du bal (1937), his story of a woman who revisits the men who danced with her one night in her youth. That plot might seem to demand a string of flashbacks, but instead it’s all played in the present. Her confrontation with what the dashing young men have become leads to a string of extraordinary encounters enacted by top players of the day (Rosay, Bauer, Fernandel, Raimu, Jouvet, Sylvie). The melancholy tone, involving a mournful devotion to impossible love, is reminiscent of Dreyer’s Gertrud.

Lydia takes the alternative option of actually dramatizing the memories of the heroine and her three lovers as they reflect on the old days. The flashbacks are daringly introduced with straight cuts and curt sound bridges; a couple of scenes use slow-motion for the past, a very unusual choice for the period. The soundtrack is unusually lush, with the brilliant Miklós Rózsa supplying lilting waltzes and even some early electronic effects. For a bold montage merging Lydia’s passion with that of the raging sea, he came up with a fierce piano concerto.

The film plays on the disparities of time and memory in a rather modern way. Flashbacks contradict one another, and what we see doesn’t always match what the voice-over tells us. Lydia in the present seems to whisper advice to the girl we see in the past, as if she’s watching the film along with us. The climax is quietly devastating: the twist was demanded by censorship, but producer Alexander Korda claimed, rightly, that it improved the film. We’re left wondering how much to trust Lydia’s memory of her idealized affair.

One thing that didn’t make it into our entry: Discussion of the peculiar cottage where Lydia and her lover Richard share their passionate idyll. It seems to be built out of the bodies of big naked people. So I share one image with you, below.

Apart from that, I hope you get to play my installment, in the waning days of FilmStruck, or maybe cached on the new Criterion Channel in the spring. You can sign up for that streaming service here, and the sooner you do it, the easier it will be to launch.

We’re grateful as usual to Peter Becker, Kim Hendrickson, Grant Delin, and the whole Criterion team, and to Erik Gunneson of the UW Department of Communication Arts. Special thanks to Daniel Reis, editor of most of our installments, whose adroit cutting strengthened them enormously. (The Lydia entry masterfully stitches together disparate sequences using Lydia’s dialogue as a voice-over.) Other entries were cut by the equally gifted Clyde Folley. Thanks as well to Kelley Conway and Phillip Lopate for conversations about Duvivier.

Criterion has served Duvivier well, offering several of his works on DVD.

A list of our Observations installments to date is here.

Lydia (1941): A house embellished with ships’ figureheads becomes the lovers’ sanctuary.