Pesky brats, adventurous ducks, and jiving swamp critters

Thursday | April 23, 2015 open printable version

open printable version

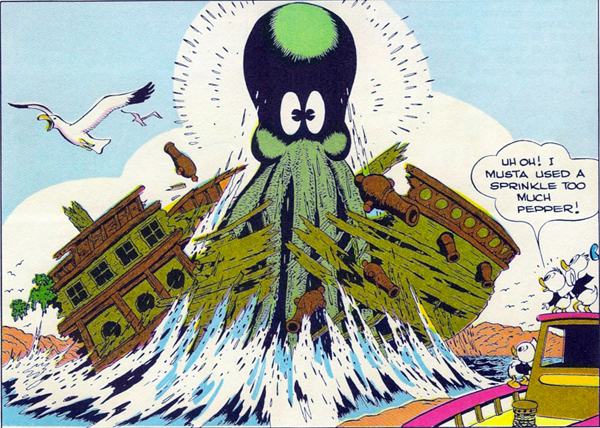

Carl Barks, Ghost of the Grotto (1947).

DB here:

We never need an excuse to write about comic strips or comic books. We’re fans and, just as important, we think of them as having important connections to film. We’re particularly fond of classic funny-animal comics, from Krazy Kat (the greatest) onward. So I got a double dose of pleasure reading Mike Barrier’s Funnybooks: The Improbable Glories of the Best American Comic Books. It taught me a lot about the history of some favorites, and it set me thinking about some overlaps and divergences between film and graphic art.

No Girls Allowed

Like Mike’s Disney book The Animated Man, Funnybooks is at one level a scrupulously researched business history. It explains how publisher Western Printing and Lithography (of Racine, WI) became the center of a thriving industry. Before the mid-1930s the company’s juvenile line came out chiefly under the Whitman imprint. Its illustrated storybooks licensed characters from Disney and comic strips like Dick Tracy and Little Orphan Annie. But Hal Horne and Oskar Lebeck pushed toward creating comic books proper, those inviting items that could compete with the superhero titles that were emerging. Their instincts were sound: Western’s comics, distributed by the Dell company, sold hundreds of thousands of copies.

After several tries at compiling daily comic strips into a single volume, Lebeck turned to original content. In the early 1940s he hired Walt Kelly, Carl Barks, and John Stanley. All had worked in film animation (Kelly and Barks for Disney, Stanley for Max Fleischer), but they adjusted to the demands of more static cartoon art. Into the rise and fall of Western and Dell, Barrier weaves the personal stories of the three creators and their less famous peers. Funnybooks is at once industrial history and a collective biography.

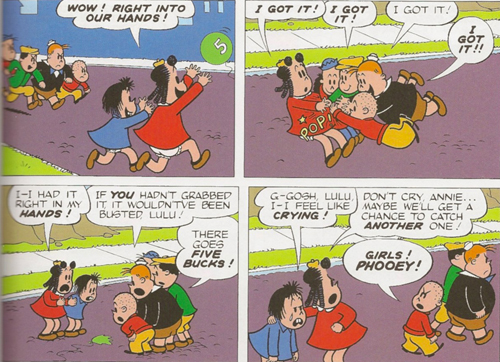

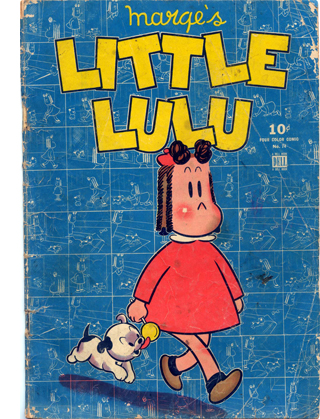

John Stanley, the least known of the trio, was brought on to do stories of Little Lulu, the stolid, crisply-curled girl created by Marjorie Buell. Stanley wrote and drew the entirety of the first book in 1945. The cover presents a heroine as blank as Hello Kitty and a background grid as febrile as a Chris Ware design. Afterward, Stanley chiefly served as writer on the Lulu stories, providing other artists with detailed scenarios and sketches. The panels might be somewhat stiff, but the plots were admirable. Often turning on mean childhood pranks, they were steeped in spite and petty revenge.

I remember enjoying Lulu’s stories, especially their verbal comedy. When Tubby (I think it was) hits Lulu with a pie, he says, “I’ve thrown a custard to her face.” Lulu replies: “I liked breathing out and breathing in.” This was probably a post-Stanley passage, but the fact that I’ve remembered it for sixty years indicates the ways grown-up jokes can stick in the unformed brain. (I knew Boris Badenov before I knew Boris Godunov.)

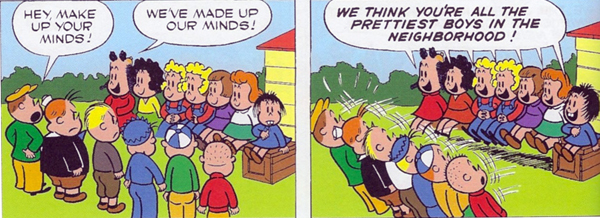

Mike is very good on the bitter humor that Stanley puts on display as Lulu and her girl pals skirmish with Tubby and his gang of sexist bullies.

His characters were never vulnerable to the suggestion so often made about the children in Charles Schulz’s comic strip Peanuts—that they were adults masquerading as children. They were instead children whose quarrels and schemes echoed adult life.

Lulu evolved, Mike shows, into a trickster who constantly showed up the boys, even as she herself was sometimes slapped down. In one story a rich boy, seeing Lulu longing for pastries in a shop window, doesn’t consider buying her one. Instead, he buys the shop and drops the shade on the window. Walking away on his golden stilts, “he felt very happy because now the poor little girl wouldn’t have to look at things she couldn’t buy.” Another compassionate conservative.

Stanley drew many other characters, including Bushmiller’s Nancy and the ingratiating Melvin Monster. His career fizzled out when comic-book publishing hit hard times in the 1950s. He wound up working in a factory that made aluminum rulers.

Rowrbazzle

Walt Kelly fared better. In the beginning he he worked on many series but he gained fame with his own creation, the enduring swampland of Pogo Possum and his friends. “Ensemble comedy,” Mike calls the remarkable menagerie Kelly assembled.

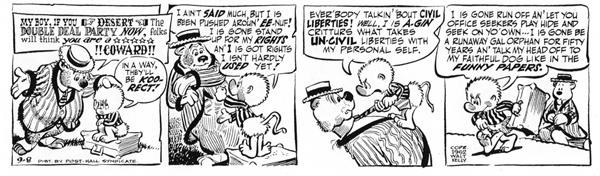

At first speaking in mangled Southern accents, Pogo, Albert the Alligator, Porkypine, Howland Owl, Churchy la Femme (another joke passing over kids’ heads), and a host of other creatures developed a patois as bizarre as the rodomontade you hear in Coconino County. Characters sang nonsense songs, recited garbled poetry, and engaged in pun-filled miscommunication. The wordplay was enhanced by lettering adjusted to different characters, notably the Gothic script associated with Deacon Mushrat and the circus-ballyhoo font employed by con artist P. T. Bridgeport.

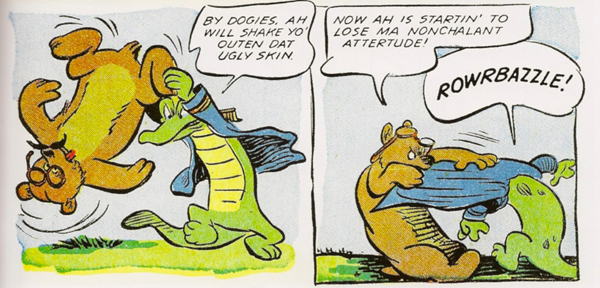

Slapstick went along with the verbal pyrotechnics. Kelly’s fluid line created complex equivalents of movie pratfalls, each one enlivened by fussy details (check the bear’s glasses below) and punctuated by unique sound effects. Barrier reports that in one Kelly comic, a cannon explodes with the sound “FRED.”

In all, eccentricity was the watchword, usually accompanied by food, or characters trying to get it. Albert had a disconcerting habit of accidentally eating his friends. Any of the crew might launch into retelling a classic children’s story featuring the entire cast. These were fairy tales not so much fractured as splintered. In all, it’s astonishing how many pictorial and verbal gags Kelly could cram into four daily panels.

Kelly, a superb draftsman, learned the secret of round forms in his Disney days, and Mike traces how this tendency toward cuteness helped make Pogo a success. But Kelly also had a nutty sense of humor that set him apart from other Western/Dell artists. Mike surveys Kelly’s range, from liberal political cartoons to Our Gang comics, and he treats with care how Kelly’s work included both racial caricatures and more affirmative images of African Americans.

Mike shows how Kelly’s talents outgrew the Dell family. As Pogo and his pals became more popular with intellectuals, the comic-book format proved a rickety vehicle for the artist’s ambitions. Kelly shifted his energies toward daily and Sunday strips that attracted nation-wide attention, not least for satirizing Joseph McCarthy and the Jack Acid (aka John Birch) Society. Pogo’s swamps, I thought at the time, became the liberal counterweight to Al Capp’s reactionary Dogpatch. Like Doonesbury and Calvin & Hobbes later, the dailies became incorporated into best-selling books published by Simon & Schuster. Those collections, to be found on every college kid’s bookshelf in the 1960s and 1970s, made Pogo as much a part of the official counterculture as Frodo Baggins. “We have met the enemy and he is us” became the slogan of a generation.

A peculiar affinity with those damn Ducks

If Funnybooks has a protagonist, it is Carl Barks. No wonder. Unlike Stanley, he both wrote and drew his books. Unlike Kelly, he was anonymous. A modest worker prized by all who knew him, he simply spent year after year turning out the beautifully crafted adventures of Donald Duck, Uncle Scrooge, and their associates. He was, it seems, born to make funny-animal comic books.

Mike Barrier is a long-time Barksian. His 1981 Carl Barks and the Art of the Comic Book is at once a biography, an appreciation, and a catalogue raisonné of this master of precision artwork. The new book fits some of Mike’s earlier arguments into the wider tale of Western and Dell, but he has also deepened his ideas about the nature of Barks’ achievement. He is able to expand his recognition of Barks’ gift for characterization, mood, and emotional expression.

Mike Barrier is a long-time Barksian. His 1981 Carl Barks and the Art of the Comic Book is at once a biography, an appreciation, and a catalogue raisonné of this master of precision artwork. The new book fits some of Mike’s earlier arguments into the wider tale of Western and Dell, but he has also deepened his ideas about the nature of Barks’ achievement. He is able to expand his recognition of Barks’ gift for characterization, mood, and emotional expression.

Instead of merely recycling an iconic character from the Disney animated shorts, Barks gave Donald his own town, Duckburg, populated by a new cast of characters—Gyro Gearloose, Gladstone Gander, the Beagle Boys, and others. Barks, it seems, gained this creative freedom because everyone at Western admired him. Mike quotes one old timer who calls Barks “the genius of the group. . . . He had a particular affinity with those damn Ducks.” Barks once thought he could support himself raising chickens. Fortunately for us, he turned his poultry fascination to comic books displaying elegant storytelling.

Here’s where Mike set me thinking about some relations between film and comics. He points out that a panel often needs to convey the passage of time—not through movement, as in film, but through devices for suggesting interplay among characters and their environment. The staging of the action, the composition, and the placement of dialogue balloons all create a rhythm of reading. Whereas Japanese manga can split an instant into many single, striking images (and thus create very long books), American comics developed ways to suggest the ripening of the story, moment by moment, within each panel.

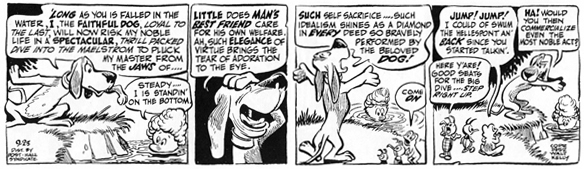

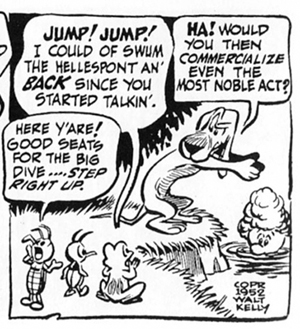

My last Pogo panel featuring the self-aggrandizing hound Beauregard is a good example.

Without the balloons, the image would be a snapshot, but the balloons produce a temporal flow. The most prominent balloon, filling about a quarter of the frame, reports the frog urging Beauregard to jump. The next balloon that we notice, snuggled against the first, shows the bug trying to exploit the rescue (“Step right up”). Farthest right, Beauregard replies to the bug, talking diagonally past the frog. The speeches are the usual Kelly demotic, incorporating low slang, literary references, and pompous rhetoric, and the order in which we read them and attach them to action accentuates the differences in diction.

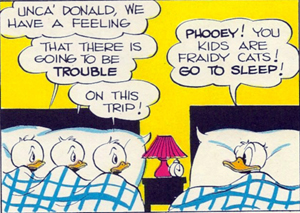

Barks could create this sense of rhythmic duration with his ready-made chorus of Huey, Dewey, and Louie. In this panel from “Frozen Gold” (1944), the cascade of balloons assumes a left-to-right reading and creates a pulse capped by Donald’s brusque reply.

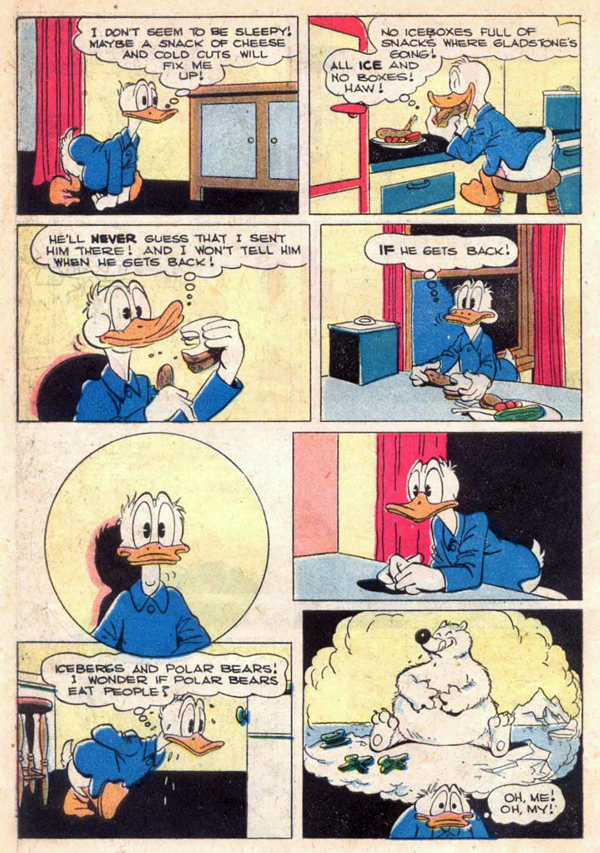

Most panels don’t create such a dense sense of time unfolding. That is more commonly achieved through several panels depicting a stretch of action. Or sometimes inaction. In a wonderful passage, Mike discusses how Barks uses a pause to suggest Donald’s growing guilt feelings after sending the odious Gladstone to the North Pole. At first he gloats, but then in a series of panels he starts to question what he’s done.

Barrier takes this page as a turning point in Barks’s evolution as an artist. Eight panels, some without action, convey a deepening psychological state, capped with an image of Donald crushed by his imagination of what could happen to Gladstone. The sense of food stuck in Donald’s craw is nicely hinted at by two motion lines near his neck.

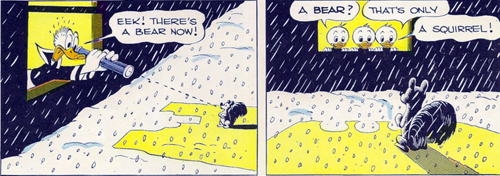

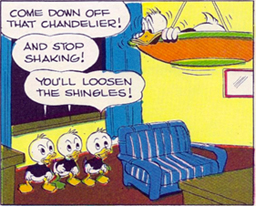

Instead of stretching action by a pause, the artist can accelerate it through ellipsis. Here’s a lovely Barks passage from “Christmas on Bear Mountain” (1947) that’s somewhat filmlike, and yet not. Huey, Dewey, and Louie are checking out a snowstorm and Donald approaches with his telescope. The suggestion is that he approaches their window from off right, with only a few steps until he gets there.

Now comes the first ellipsis: The boys have left the window, and Donald is already spotting what he thinks is a bear. This is very concise storytelling. A sharp change of angle shows another ellipsis: the boys are back at the window identifying the squirrel.

In the “cut” between panels 3 and 4, Donald has disappeared. Where’d he go? The next panel shows us.

The jumps in time are covered by the smoothly varied compositions: 1 and 2, sitting side by side, flow neatly, while 3 and 4, overlapping pictorially, actually cover a time gap. The gap is filled by panel 5, a nice variant on what we saw in 1 and 2. You’d seldom find cuts like these in a film, though I’d welcome somebody trying.

I don’t want to give the impression that Funnybooks is a theoretical study. Mike Barrier, who has thought seriously about the aesthetics and history of comics for fifty years, has given us another precious historical account of this extraordinary popular art and three of its masters. It’s up to us to recognize how his discoveries can shed light on pictorial storytelling generally.

P.S. 28 April 2015: Funnybooks has been nominated for an Eisner Award. Congratulations to Mike! Another fine nominee is Thierry Smolderen’s The Origins of Comics: From William Hogarth to Winsor McCay (University Press of Mississippi), translated by Bart Beaty & Nick Nguyen.

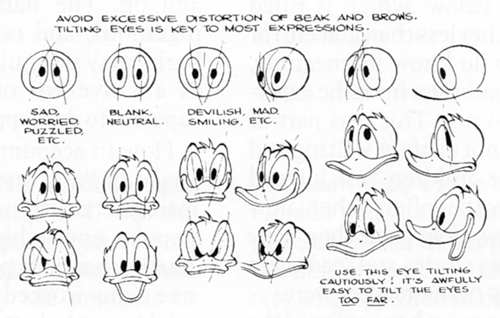

My illustrations are drawn from The Best of Walt Disney Comics 1944 and The Best of Walt Disney Comics 1947 (Western Publishing, n.d.); Walt Kelly, Pogo: The Complete Dell Comics, vol. 2 (Hermes, 2014); Walt Kelly, Pogo: The Complete Syndicated Comic Strips, vol. 2: Bona Fide Balderdash (Fantagraphics, 2012); and Little Lulu Color Special (Dark Horse, 2006). The model sheet of Donald heads comes from Mike Barrier, Carl Barks and the Art of the Comic Book (M. Lilien, 1981), 43.

Thanks to Hank Luttrell of Twentieth Century Books for helping me find some rare items. And be sure to check Mike Barrier’s encyclopedic website. His 23 April entry rounds up several reviews of Funnybooks.

If anyone reading this doesn’t know Scott McCloud’s superb surveys of the art and craft of comics, I should mention Understanding Comics (Morrow, 1993) and Making Comics (Morrow, 2004). Both books contain many observations on how comics manipulate time.

Looking back at my blog entry on Tintin, I think that the sense of time unfolding within the frame is what Hergé was getting at when he picked a certain image of Captain Haddock as the essence of his method. In the same entry, I suggest that Hergé was creating continuity and ellipses in ways similar to Barks’s Bear Mountain story. Still, Hergé offers more tightly constrained choices of angle and less drastically changing compositions.