Archive for October 2012

More of the world in a multiplex: another dispatch from Vancouver

Kristin here:

Latin America

In my first report, I mentioned that the Iranian film A Respectable Family was an unexpected gem. I’ve come across another, the Brazilian film, Neighboring Sounds (2012). It has a remarkable formal device that unfortunately I can’t disclose without ruining the film for those who haven’t seen it. It’s a technique that takes a while to figure out, since it’s cumulative. (Fortunately, unlike with A Respectable Family, I have yet to find a review or program note that mentions it.)

The film is set in Recife, the fifth largest city in Brazil. It centers around members of two families living in a complex of smaller, older houses surrounded by new condo high-rises that will eventually swallow the entire area. (The image above vividly shows the juxtaposition.) The divide between rich and poor is extreme, however, and the residents live in fear of crime, with elaborate gates and with grilles over their windows. Suspense is generated when a small group of men offer their services to provide security for the block, and once they are hired, we are left for a long time to wonder whether this is a cover for some other devious purpose.

The film is beautifully shot, taking advantage of the abstract compositions created by the modern apartment blocks and their glass windows and doors. As director Kleber Mendonça Filho says in the online press kit, “Architecture gone wrong is a nuisance, but extremely photogenic.”

The film’s title is taken literally, with many layers of offscreen sounds from nearby houses and streets forming much of the soundtrack. The complex use of Dolby Surround makes it especially desirable to view and listen to this film in a theater.

Neighboring Sounds has been picked up for US distribution by the Cinema Guild, which has handled other films we’ve enjoyed here in Vancouver , most notably Once upon a Time in Anatolia and The Strange Case of Angelica (and written about here and here, both available on DVD and Blu-ray.)

The Chilean film No (2012), starring Gael Garcia Bernal, has already gained a high reputation on the festival scene. (Like A Respectable Family, it was shown in the Directors’ Fortnight at Cannes.) David and I both thought it lived up to its buzz.

The plot deals with the 1988 referendum as to whether dictator Augusto Pinochet would remain in power. The side campaigning for the “no” vote was allowed a single 15-minute TV commercial each evening. Bernal plays a successful director of TV ads, Rene, who is lured into devising this commerical; he’s introduced showing off his latest spot for “Free” cola. He conceives of a campaign based on breezy optimism, with musical numbers (below right) and shots of cheerful workers acting as if Pinochet is already out of office. His tactics disgust several of the left-wing party leaders, as well as Rene’s estranged wife.

Technically the film is cleverly done. It was shot on old-fashioned U-matic video and shown in Academy ratio (not exactly reflected in these frames from the online trailer). Fuzzy images with occasional overexposure and other video artifacts not only suggest a period piece, but they also allow director Pablo Larraín (Tony Manero, Post Mortem) to seamlessly edit in historical footage of Pinochet and street clashes from 1988. No generates considerable suspense as well, whether or not one knows how the referendum turned out.

Sony Pictures Classics picked up No at Cannes and currently lists its release date as to be announced; according to IMDB, it will have a limited release in the USA on February 15.

Europe

A Royal Affair (2012, Nikolaj Arcel) has been chosen as Denmark’s entry for the Best Foreign Language Film Oscar. Of course, the long list of entries from various countries will be reduced to five before the voting occurs. Still, I wouldn’t be surprised if A Royal Affair ended up on the final list and even took the top award. In a way, it’s just what the Academy members like: a big, glossy costume drama based on uplifting historical events.

But I was relieved to discover that this is no Merchant-and-Ivory-style middle-brow adaptation. It’s a fascinating example of what happens when a bunch of leftist, cutting-edge filmmakers get their hands on a budget to make an historical epic. Although the film’s title and publicity center on the illicit romance that provides part of the drama, A Royal Affair focuses largely on politics. Its plot is loosely based on historical events during the Age of Enlightenment, during which Denmark initially remained a backward country based on serfdom, summary arrest, torture, and execution, and grinding poverty for the lower classes.

The opening shows the heroine, Caroline, born an English princess and wed to Danish King Christian VII, writing the story of her life for her children. A flashback then begins the story proper, with Caroline optimistically setting out for Denmark and quickly discovering that her husband is an impetuous, rude and possibly insane young man who cares nothing for her. Her loneliness and the backward situation in Denmark are gradually established. Eventually a young doctor, Struensee, who believes in the ideas of the Enlightenment philosophers, comes to court and befriends the king, helping him to behave in a more restrained fashion.

Caroline, too, is a devotee of Rousseau, Voltaire, and other authors whose works are banned in Denmark. Nearly an hour  into the film, she discovers that Struensee is of like mind, and a friendship gradually moves into love and a sexual affair. The couple manipulate Christian into passing laws to benefit the peasants, earning the ire of the nobility. The narrative continues to center more on the social struggle that the three carry out than it does on the romance plotline.

into the film, she discovers that Struensee is of like mind, and a friendship gradually moves into love and a sexual affair. The couple manipulate Christian into passing laws to benefit the peasants, earning the ire of the nobility. The narrative continues to center more on the social struggle that the three carry out than it does on the romance plotline.

When I heard that the Silver Bear for Best Actor was awarded to the film at Berlin, I assumed it went to Mads Mikkelsen, who plays Struensee–and seems to star in half the films coming out of Denmark these days (such as Thomas Vinterberg’s The Hunt, also shown this year in the festival). But the role of Christian VII actually seemed to me more challenging. Mikkel Boe Følsgaard has to play a character who begins as border-line insane, crude, and obnoxious, but who also must gain our sympathy when he becomes part of the plot to reform Denmark’s laws. I was delighted to learn upon further inquiry that is was in fact Følsgaard (on the left, with Mikkelsen, in the photo) who won the award. Well deserved.

As the image suggests, the film is shot in muted tones that tend to play down the costumes and sets more than historical dramas usually do. This approach helps direct our attention to the plot and politics rather than the pageantry. In short, I ended up liking the film much more than I expected to.

A Royal Affair will be released in the USA on November 9 by Magnolia Pictures.

At the other end of the budgetary scale is the Portuguese feature The Last Time I Saw Macao (2012, co-directed by João Pedro Rodrigues and João Rui Guerra da Mata). A common impulse among critics seems to be to compare this mysterious, lyrical film to some of Chris Marker’s works. There is little information available on it, but my impression was that the filmmakers shot a lot of lyrical footage of Macau and then concocted a story to fit it. There are shots of buildings, from skyscrapers to disreputable-looking back streets, as well as ephemeral items like some big, gaudy, cartoony balloons of tigers that decorated the streets for a local festival.

The plot has something to do with a mysterious gang, the Chinese zodiac (see image at the bottom), and the end of the world. The hero is barely glimpsed, narrating the story in voiceover (provided by both of the directors). The plot centers on his search for a transvestite named Candy, perhaps the “woman” seen performing a musical number in front of a cage containing live tigers in the sultry opening scene. The song, “You Kill Me,” is among several references to Josef von Sternberg’s Macao.

Despite the shoestring budget, the filmmakers manage convincingly to portray an apocalyptic destruction of the city, followed by bleak shots of deserted, early-morning Macao buildings that effectively suggest the aftermath. It reminded me of Godard’s depiction of a futuristic city in Alphaville, using contemporary buildings and highways.

No US release is planned, but The Last Time I Saw Macao is worth seeking out at upcoming festivals.

A Filmmaker of the World

I’ve mentioned some films that pleasantly surprised me, but almost certainly the best film we saw at Vancouver came as no surprise at all. We both loved Abbas Kiarostami’s Like Someone in Love, but we’re not going to write anything substantive about it, at least not now. It deserves another viewing or two before we could say anything worthwhile–and it hardly needs us to publicize it. The opening scene is fabulous, the subsequent rambling plot absorbing and intriguing, and the end, as so often happens with Kiarostami, puzzling and frustrating. Possibly the man can do no wrong.

IFC has theatrical rights for the USA. Currently its webpage announces “Coming in 2013.” This may mean primarily On Demand, though it would be a pity not to see Like Someone in Love on the big screen.

The end of one multiplex

Rumors circulated almost from the start of the festival, and on October 8 the festival’s director, Alan Franey, revealed officially that the Empire Granville will soon be closing down. A detailed story on the history of the Granville and its closing, with quotations from Franey and representatives of other film festivals that have used the venue, can be found here. Ideally next year’s festival will house most of its screenings in another of the city’s multiplexes, but the new venue is yet to be determined. We hope it will be someplace where we can bounce around the world from screen to screen as easily. The Granville has served us all well and will be missed.

Make mine music, not to mention pictures

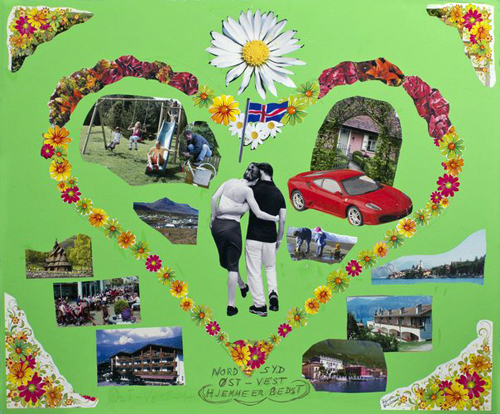

Collage by Sigrídur Níelsdóttir.

DB here:

The Vancouver International Film Festival has had strong commitments to certain types of cinema–Asian, Canadian, environmentally-sensitive documentaries, and perhaps least well-known, arts documentaries. I still recall seeing The Red Baton, a vivid account of Russian musical life under Stalin, at my first VIFF visit in 2006, and ever since I’ve tried to check out at least a few entries in this category. They’re not usually very daring formally, but they do open up areas of the arts that I cherish, and–just as important–areas I’m completely unaware of.

Childhood and the morning of the world

For instance, as an admirer of comic strips and comic books, I had to see Josh Melrod and Tara Wray’s Cartoon College. The institution in question is the Center for Cartoon Studies at White River Junction, Vermont. (Go here for the most educational college catalog I’ve ever seen.) Each year twenty students are admitted for the two-year MFA program, and the film follows several as they move through the curriculum.

Don’t be misled by the black clothes, Kool-aid hair, and cats’-eye glasses. These kids aren’t your usual Art School posers. They want to tell stories. Jen explores menstruation; Al, the 61-year-old Boston archaeologist, takes time off to learn to draw; and Blair the Mormon wants to chronicle his missionary work. Interviews with Lynda Barry, Art Spiegelman, Charles Burns, and Chris Ware are salted through this story of intense work, achievement, and occasional disappointment.

Don’t be misled by the black clothes, Kool-aid hair, and cats’-eye glasses. These kids aren’t your usual Art School posers. They want to tell stories. Jen explores menstruation; Al, the 61-year-old Boston archaeologist, takes time off to learn to draw; and Blair the Mormon wants to chronicle his missionary work. Interviews with Lynda Barry, Art Spiegelman, Charles Burns, and Chris Ware are salted through this story of intense work, achievement, and occasional disappointment.

One accomplishment of the film is to remind us of the very unusual qualities needed to be a cartoonist. There’s the patience of drawing hundreds of panels, and sometimes the same figure in hundreds of different postures, along with the hours of fine-grain line work and coloring. There’s also the sense that of all artists, cartoonists are most in touch with childhood, that period, as Ware remarks, when each experience is “rich and warm . . . and days seem to last for weeks.”

Perhaps that’s why the students radiate that awkward innocence that’s easily mocked. They explain how they didn’t fit in with their high-school milieu; one man recalls that people assumed he was either gay or a British exchange student “because I didn’t contract all my g’s and used proper English.” The great thing students find at CCS, says Spiegelman, is that “instead of being the outcast in art school you get to be with a bunch of other outcasts.” Yet these outcasts bond, forming couples and offering group critiques, and cooperating on projects for conventions and festivals. Cartoon College teaches you a lot about cartooning, but it also reminds you of the vitality of young imagination.

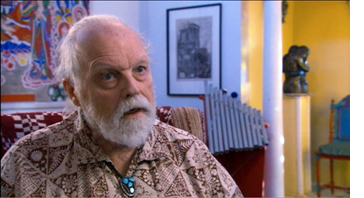

Lou Harrison, whom I knew chiefly as a pioneer of melding non-Western music with classical traditions, proved to be a fascinating figure in Eva Soltes’s Lou Harrison: A World of Music. This biographical account showed me that this man often considered marginal–far less well-known than Copland or Bernstein–in fact thrived at the center of the bohemian world of American music. He went to Mills College, taught at Black Mountain College, hung around with Henry Cowell and John Cage and Virgil Thompson, collaborated with Merce Cunningham and Mark Morris, and conducted the premiere of Ives’ monumental Third Symphony.

Harrison was open to every influence, from Schoenberg’s serialism to Harry Partch’s unorthodox instrumentation. He drew on Korean and Taiwanese music and Javanese Gamelan, and even composed pieces for Geiger counters (as a protest against nuclear testing). The result is music of great delicacy, with sumptuous textures and fluid melodies. Go here to listen to some samples.

Harrison was open to every influence, from Schoenberg’s serialism to Harry Partch’s unorthodox instrumentation. He drew on Korean and Taiwanese music and Javanese Gamelan, and even composed pieces for Geiger counters (as a protest against nuclear testing). The result is music of great delicacy, with sumptuous textures and fluid melodies. Go here to listen to some samples.

Like many of his peers and collaborators, Harrison was gay, and he wasn’t shy about saying so. The partner of his later years, Will Colvig, lovingly crafted unique instruments for his compositions. After Colvig’s death, Harrison struggled to put onstage Young Caesar, a gay-centered opera–for puppets, no less. “Lou was always out of fashion,” reflects conductor Michael Tilson Thomas. Unfashionable or not, Harrison left us music of pulsating lyricism and quiet, unforced radiance. The film’s celebration of this American original deserves wide circulation. Now a personal request to Ms. Soltes: How about Alan Hovhaness next?

Nordic thaws

Then there were two films that opened my ears. I wasn’t prepared for the brawny music of Kimmo Pohjonen, who is on roaring display in Kimmo Koskela’s Soundbreaker (aka Ice Bellows). Along with street mimes and face-painters, accordion playing has become a bad joke, but Pohjonen makes it a contact sport. Built like a torpedo, with short hair razored to a cellbock edge, he plays his amplified squeezebox like he’s grappling with a python. Our musician is first shown tramping across a frozen lake and then plunging through a hole before taking up his instrument and playing underwater.

It’s a nice introduction to Extreme Music, Finnish style. Thereafter, a mixture of concert footage and daily routine takes us into a world like Lou Harrison’s, where any sound can become music. Pohjonen will solo with the Kronos Quartet or with chugging farm machinery (the clip is here). Soundbreaker was the first film I saw in my VIFF visit. After hearing this infectious wahoo music, I ordered some albums. Consider doing the same.

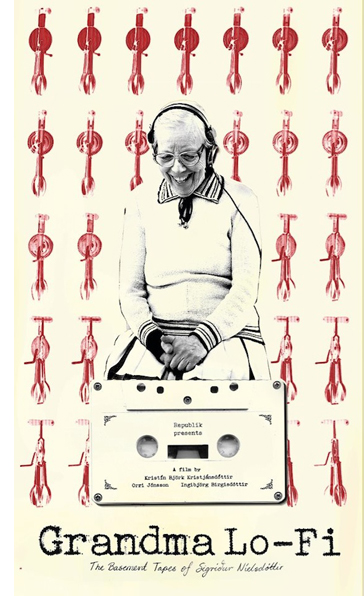

Speaking of Nordic revelations, there’s Grandma Lo-Fi: The Basement Tapes of Sigrídur Níelsdóttir. I can’t do better than quote the VIFF catalog, describing a lady who

decided to become a musician at the unlikely age of 70. Equipped with little more than a cassette recorder, cheap keyboards, common household items, and an adventurous spirit, she crafted an astonishing 59 albums in a mere seven years and became a DIY icon for a generation of Icelandic musicians.

Since some of those musicians include ones I follow, like múm, I had to catch up with Sigrídur.

Born in Denmark to a German mother and Danish father, she learned a little piano as a child. Later, after her sweetheart was lost at sea, she left her parents and made her own way. Parts of her life are hazy, but she wound up in Iceland with several children. Having worked as a shopkeeper, dog-walker, and lacemaker, she settled in old age in a basement apartment, where she began composing at a keyboard she called her “entertainer.”

Born in Denmark to a German mother and Danish father, she learned a little piano as a child. Later, after her sweetheart was lost at sea, she left her parents and made her own way. Parts of her life are hazy, but she wound up in Iceland with several children. Having worked as a shopkeeper, dog-walker, and lacemaker, she settled in old age in a basement apartment, where she began composing at a keyboard she called her “entertainer.”

Thanks to a double-tape boom box, she could dub and redub her compositions, often reusing commercial audiocassettes discarded from her library. Her music and voice were garnished with animal sounds (including barking dogs and cooing pigeons) and kitchenware noises. Eggbeaters made good helicopters, cheese graters evoked shamisens, and tinfoil provided campfire sounds. “Everyone is free to use these things. I don’t charge.” Like the rest of us, she self-publishes.

She filled her apartment with religious images and awoke at 4:30 AM to pray and read the Bible. Music, she says, taught her what the Bible really means. When she couldn’t sleep, she chirped to the birds; for all she knew, she might have been swearing in bird-talk. After 687 original songs, some dedicated to friends and family, she abruptly stopped her musical career and turned to cut-and-paste art. Her collages, like her music and album graphics, display simple geometric structures overwritten by doodlish embellishments, marks of classic “naive” or “outsider” art. But now outsider art inspires everyone.

The film, by Orrí Jónsson, Kristín Björk Kristjánsdóttír, and Ingíbjörg Bírgisdóttir, mimics the low-tech quality of Sigrídur’s oeuvre with rashes of graininess, images reminiscent of 8mm and VHS, and some self-conscious animation and SPFX tableaus featuring pop artists indebted to her. But the film isn’t mocking this remarkable woman, who perpetually grins in modest pride. As she tells us, “I don’t think you can do any harm with songs like these, right?” Like Lou Harrison, who was composing in his eighties, Sigrídur easily rivaled the energy and passion of Pohjonen and the kids of Cartoon College. Art keeps you young, as if you didn’t know.

I learn from many VIFFers that Alan Franey, Festival Director and CEO, is the guiding spirit behind the festival’s commitment to arts documentaries, and particularly those focused on music. For this and many other things, Kristin and I owe him our thanks.

10 October 2012: Thanks to Olli Sulopuisto for a major correction; I had initially called Pohjonen an Icelandic musician. Thanks to Olli as well for correcting a misspelled name.

Young Caesar, opera by Lou Harrison (1971).

Stretching the shot

Walker (2012).

It’s the editor’s job to think about coverage, and mistakes at this stage can have a very high price. Without that shot of the murderous feet walking slowly down the stairs, it’s impossible to build suspense. Inexperienced directors are often drawn to shooting important dramatic scenes in a single take—a “macho” style that leaves no way of changing pacing or helping unsteady performances.

Christine Vachon

DB here:

Go to any ambitious film festival, such as the Vancouver one Kristin and I are attending at the moment, and you’ll see several films made up of unusually sustained shots. Some Asian and European films may even be made entirely of long takes; in a few instances, none of the scenes may employ any editing at all. Movies made wholly of one-take scenes, or sequence-shots (plans-séquences) are probably more common today than they have been since 1920.

Why so many long takes? In the 1990s, when Vachon was writing, imitation and competition probably did come into play. The Movie Brats were sometimes up-front about their boy-on-boy rivalry. Here’s De Palma after seeing the shots following Jake into the ring in Raging Bull:

I thought I was pretty good at doing those kind of shots, but when I saw that I said, “Whoa!” And that’s when I started using those very complicated shots with the Steadicam.

Something similar may have been going on in earlier times. It seems to me that in 1940s Hollywood, directors came to a new consciousness of the long take. Preminger, Ophuls, Sturges, and Welles became famous for their sustained shots, and even Hitchcock, a long-time proponent of editing, switched sides, making some of the longest-take films of the era. Sometimes an action scene might be played out in one flamboyant take, as in The Killers and Gun Crazy. It does seem that these big boys appearing to compete to see how long they could hold their shots and how complicated they could make them. One scene in Welles’ Macbeth runs a full camera reel, or about ten minutes; Hitchcock’s Rope contains only eleven shots.

Yet I don’t think that macho showoffishness or competition can completely explain the urge to shoot long takes. Watching the Vancouver Dragons and Tigers series leads me to consider some other options.

Long view of the long take

Naniwa Elegy (1936).

Of course there were single-take movies at the beginning of cinema, as in Lumière’s documentary shorts. And in the period 1908-1920, as I’ve argued in many entries on this site, some great films were made relying on single-shot scenes. They operated with a staging-driven aesthetic that’s come to be known as the “tableau” style.

But with the rise of American cinema to international prominence, and worldwide directors’ willingness to create scenes in the process of editing, the long take became relatively uncommon. In the 1920s, a rapidly-cut film might make occasional use of a long take, often as a fairly intricate traveling shot, as in Murnau’s Sunrise and Vidor’s The Crowd. Early talkies sometimes began with a long tracking shot (e.g., Sunny Side Up, Scarface) before settling into a more editing-driven style. And a few directors in Western cinema, like Max Ophuls, Jean Renoir, and John Stahl, handled extended dialogue passages in a single shot. A long-take approach was somewhat more common in Japanese cinema, with of course Mizoguchi Kenji being a prime exponent in films like Naniwa Elegy, Sisters of Gion, and Genroku Chushingura.

Citizen Kane probably helped popularize the long take in the 1940s, but so did the development of new camera supports. Dollies that could move through a set in tight turns encouraged directors to try out more sustained shots. For such reasons, most long takes of the period involved camera movement. Although Welles had his share of flashy tracking shots, he was one of the few directors who also let the camera stay fixed in place throughout a scene, in both Citizen Kane (Toland emphasized its “single, non-dollying” shots) and the extraordinary kitchen scene of The Magnificent Ambersons.

Occasional long-take shots have been with us ever since, some of them highlighting balletic camera-actor staging, as in Antonioni’s bridge encounter in Story of a Love Affair and many interior shots of Le amiche. By the 1960s, and 1970s, some directors became identified with long takes and even single-shot sequences: Tarkovsky most famously, but also Straub and Huillet, Miklós Jancsó, and Theo Angelopoulos. Fassbinder tried it out occasionally (Katzelmacher) as did Wenders (Kings of the Road). And of course in the avant-garde, devastating half-hour shots marked some works by Andy Warhol, not your most macho filmmaker.

There are still long-take films being made in the mainstream—not only those motivated as scavenged recordings like Cloverfield or Paranormal Activity, but also ambitious experiments like Children of Men. On the whole, however, long-take technique has become a hallmark of festival cinema. As commercial directors (not just in Hollywood) has embraced ever-faster cutting, other filmmakers have pushed toward ever-longer takes. It’s as if the rise of what I’ve called intensified continuity has provoked filmmakers to go to the other extreme. This impulse is thrown into still sharper relief by the fact that many of these festival films use little camera movement. And today’s shooting on video lets you hold shots a lot longer than shooting on camera reels.

But what does long-take cinema buy you?

Dragons, tigers, and stillness

A Mere Life (2012).

This year’s Dragons and Tigers series, the festival’s panorama of recent Asian cinema, had its usual quota of young people’s films about young people, not unlike America’s Mumblecore. The kids hang out, smoke, drink, flirt, berate each other, sometimes humiliate one another, occasionally come to a crisis in their lives. Other films were a bit more unusual. Several of all types, though, pointed up the virtues and limitations of current approaches to long-take shooting.

Most low-budget directors employing long takes don’t do so out of bravado or competitiveness. The reasons are more mundane: the tactic saves time and money. If you have rehearsed your actors, or if you want spontaneity and improvisation, you can get through a lot of your film more efficiently if you simply record the action. Editing in post-production comes down to choosing your best takes and finding the best arrangement of them.

For instance, Ninomiya Ryutaro’s The Charm of Others has about fifty shots in its eight-five minutes. Most scenes consist of only one or two shots. One seven-minute shot shows a young layabout Sakata trying to jolly his girlfriend out of dumping him. She’s seen him with another girl and tells him, “Eat first, then we’re through.” Instead, he pokes and tickles her, makes faces and jokes about liking to eat hair, and eventually wins her back. It’s a nice little examination of how men turn boyish, even babyish, when they’re trying to avoid a woman’s wrath.

Ninomiya, who plays Sakata, explains that although he had each scene’s core action fully scripted, he let actors improvise a fair amount during shooting. (Some specific words, however, had to be used.) The girlfriend scene was shot four times, the first three developing one approach to the action and the fourth take trying a totally different approach. Ninomiya wound up using the third take.

The Charm of Others is shot in a loose handheld style, with panning and tracking to follow its characters. This “free camera” technique is probably the most common way off-Hollywood directors employ the long take. The approach was on display as well in Mine Goichi’s The Kumamoto Dormitory. The plot follows a pair of slackers who want to work in films but lack ambition and anything approaching realistic expectations. More editing-driven, and somewhat more slickly made than The Charm of Others, it still averaged about eleven seconds per shot, a far cry from contemporary Hollywood’s average of five seconds or less.

For the most part, The Kumamoto Dormitory uses long takes in traditional ways–to record a scene’s interactions, and sometimes to create parallel story situations. In the beginning a lengthy shot drifts along dorm corridors as kids are moving in. One later in the semester shows boys in each room masturbating, playing mahjongg or computer games, and otherwise goofing off. Near the end another traveling shot shows the boys packing to leave as we hear an admistrator’s public speech describing how dorm life brings beginning students and graduating ones closer together. His inspiring line, “You were brought into the world because you were needed,” becomes ironic in the light of the dead-end hopes of a would-be movie director and his pal, an aspiring stunt man.

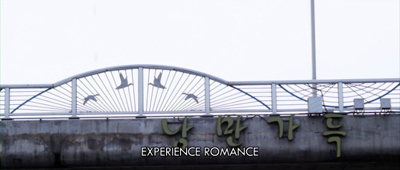

More rarely, the camera can be locked off during the long take, creating a static setup that may be refreshed by slight pans and reframings. Two of the films I’ve discussed earlier, Romance Joe and In Another Country, exemplify this approach; the former has fewer than 200 shots, the latter fewer than seventy. A similar approach, with a little more emphasis on dramatic compositions, is taken in Park Sanghun’s A Mere Life, a movie not about twentysomething crises but about the failure of a man to provide security for his wife and child. In a somewhat Mizoguchian tale of misery, most scenes are covered in only one or two fixed shots. There’s a striking scene in a café which obliges us to scan the background when a con artist bilks the husband and flees with his money. At another point, the camera’s refusal to budge and the director’s refusal to cut create considerable tension. Soon after the husband has lost the family’s savings, walls block our view of his desperate attempt to kill his wife and child.

The static long take is used in a more transparent way in Luo Li’s Emperor Visits the Hell, the winner of the Dragons and Tigers competition. The curious premise is that characters in present-day China are reenacting an episode in the classic saga Journey to the West. The reenactment, moreover, isn’t an affair of costumes or combat. It’s more abstract. For instance, the Dragon King is decapitated in the original story, but the Triadish character playing him in this film strolls around with his head firmly in place.

There are few single-take scenes, but the starkness of the décor and the fact that characters tend to be planted in a single spot give the film a sense of ceremonial gravity enhanced by the precise choices of camera position. Only in an epilogue, during the production’s wrap party in a restaurant, do the cast and crew assume their everyday identities. Then the camera goes handheld and roams bumpily around the table.

By the end Emperor Visits the Hell becomes a collection of contemporary long-take options: fixed versus moving, rock-solid framing versus shakycam.

Time on our hands

The long take has, we’re often told, another purpose: to capture real duration. Editing, it’s said, fragments not only space but also time. Whenever you cut, you have the opportunity to skip over dead moments. With a long take, especially a static one, the filmmaker is in effect asking us to register all the dead time between more important gestures, expressions, or lines of dialogue. This happens again and again in The Charm of Others, The Kumamoto Dormitory, and most of the movies I’ve already mentioned.

But the assumption of that “real time” flows through the shot can be questioned. The most common counterexample is slow- or fast-motion, which doesn’t respect the actual duration of the action the camera records. A rarer instance is offered by Tsai Ming-liang’s episode Walker in the portmanteau project Beautiful 2012, sponsored by the Hong Kong International Film Festival Society.

The action is bare-bones: A Buddhist monk walks through Hong Kong bearing a crinkly plastic bag in one hand and a sweet bun in the other. Across twenty-four minutes, twenty-one shots trace his progress through the city. In most the camera never movies, capturing the monk’s movement in static, sometimes abstract compositions. The catch is that the monk, played by Tsai regular Lee Kang-sheng, is advancing with preternatural slowness.

Sometimes we have to play a sort of Where’s-Waldo game with the compositions, searching for his stooped head or brilliant red robe or bare feet in a crowded shot. Most often, the emphasis falls simply on the monk’s movement. Hands lifted, head bent, he makes his way as if walking underwater. We watch each foot lift, shift weight, and descend in excruciatingly small changes of position. The movement proceeds not from camera trickery or CGI gimmicks; Lee’s performance presents a “temporal close-up” of humble, unstoppable walking. Meanwhile traffic, passersby, and other parts of his surroundings bustle along as usual. This is really stretching the shot–making the long take seem even longer.

One effect of these shots is to unroll an image of pure spiritual discipline, a sort of Zen exercise showing how microscopically an adept can control his body. Pedestrian yoga, you might say. Another effect Tsai creates is to summon up two times in one shot: that of normal activity and that of a spiritual tempo nestled within, but also opposed to, ordinary life. Eventually, when the monk bites into the bun, even that is rendered with the clarity of stop-motion photography. Here the long take exercises an almost scientific force, letting us see a simple act pulverized, as if a Muybridge image were translated into live action.

At the opposite extreme is the action-packed long take, running about seventy-five minutes, that comprises J. P. Sniadecki and Libbie D. Cohn’s People’s Park. The filmmakers had the good idea of taking us through a day’s pleasure in the city park of Chengdu, China, by means of a single traveling shot. A modern version of People on Sunday, the film unrolls a pageant of the everyday. People snack, trot past, make cellphone calls, rest on benches, sketch calligraphy on the paving stones, and above all make music. We see band concerts, karaoke performances, traditional opera, and spontaneous dancing to pop beats. The film starts with couples dancing and ends with an exuberant display of bouncy soloists who, we learned from Libbie Cohn after the screening, come often to perform for the sheer fun of it.

Just as important, instead of shooting at eye level, Sniadecki and Cohn filmed from a wheelchair. The lower-than-normal framing emphasizes kids, fills the frame with torsos, and yields unexpected revelations of figures in depth. We also get to watch a choreography of politeness as people subtly adjust to the camera as it squeezes through crowds or sidles among couples on a dance floor. Far from being the weightless, invisible camera of most Hollywood films, this camera and its carriage occupy actual space as the whole unit carves a sinuous path through the park. How, we sometimes wonder, will it get through here?

Many of the most famous long takes in film history are, we might say, teleological: They build toward a climax. Think of the tracking shot that opens Touch of Evil, beginning with a bomb set ticking and ending with an explosion. In a quieter way, the tableau aesthetic of the 1910s often gave the shot a distinct curve of interest, building to an expressive peak. (See here and here.)

And occasionally in today’s cinema, a shot that seems casual will subtly prepare us for a payoff. In The Charm of Others, a drinking game allows Sakata to tell others around the table what they must do. He orders two boys to kiss, and the girls join him in chanting, “Kiss! Kiss!” Those boys have already been present from the start of the shot, but now they become more than a pair of framing shoulders. Their obeying the order close to us furnishes an enjoyable topper for the take.

One problem facing the makers of People’s Park was the need to provide such a climax. As in Russian Ark, a single-shot feature film can’t simply stop; it needs to draw to a close, preferably on a striking note. In my view, Sniadecki and Cohn manage it. It would be unfair to tip you off–can there be such a thing as a stylistic spoiler?–but let’s just say it’s a moment of abrupt change within what is otherwise continuous, evenly-paced unfolding. Yes, dancing is involved.

In certain contexts, a long-take trend can, as Vachon mentions, exude a certain bragadoccio. Competition among artists, though, even with some bravado, isn’t necessarily a bad thing, as 1940s and 1980s Hollywood suggests. Sometimes as well the long take is an exigency demanded by time and money. It can yield artistic advantages, too, by building suspense (as in A Mere Life) or surprise (as in The Charm of Others) or both (as in People’s Park). It can also be a mark of virtuosity, a quality prized in most artistic traditions. A well-done long take can be like a sustained aria in an opera; its confident audacity can make you smile.

The epigraph quotation is from Christine Vachon’s Shooting to Kill (Morrow, 1998); the passage is available here. My quotation from Brian De Palma comes from “Emotion Pictures: Quentin Tarantino Talks to Brian De Palma,” in Brian De Palma Interviews, ed. Lawrence F. Knapp (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2003), 148. I discuss stylistic competition in contemporary American film in The Way Hollywood Tells It.

I consider Mizoguchi’s use of the long take in Chapter 3 of Figures Traced in Light. Some elaboration of that chapter is on this site.

Toland’s explanation for avoiding cutting is explained in his essay “Realism for Citizen Kane,” available here. For more on his decision-making, see our book, The Classical Hollywood Cinema: Film Style and Mode of Production to 1960, as well as this blog entry. For more on 1940s “fluid camera” technique, go here.

The segments of the film Beautiful 2012 began life as online videos. They are linked at Hong Kong Cinemagic. They play rather jerkily on my laptop, but the motion in projection is completely smooth.

My thanks to Tony Rayns and Shelly Kraicer, programmers of the Dragons and Tigers series, for their acumen and assistance.

People’s Park (2012).

Memories are unmade by this

Romance Joe (2011).

DB here:

The Vancouver International Film Festival always provides a host of intriguing experiments with narrative form. This year the Dragons and Tigers series, devoted as usual to new films from Asia, offers such a neat pairing of a veteran director and a newcomer that I can’t resist spending some time on them. Both, it turns out, are interested in memory–not just as a theme, but rather as a process involved in how we watch movies.

Passion for pattern

When we analyze a film, we usually notice patterns—an arc of character development, repeated imagery or musical motifs, recurring framings or lines of dialogue. Filmmakers use these elements of patterning to give elements special significance.

Sometimes the patterns we pick out are noticeable on our first viewing of a movie. Indeed, the film’s effect relies on our seeing later elements as completing a pattern.

Remember “You complete me” from Jerry Maguire? The reason you do, I think, is partly because its first appearance is very salient. It occurs when Jerry and Dorothy are riding in an elevator with a mute couple. Dorothy’s explanation of the couple’s signing highlights it (while characterizing her as a sympathetic person who learned ASL to communicate with a relative). When Jerry restates it in Dorothy’s living room, we recall that it’s a simple declaration of love—a straightforward statement from a man who is habitually slick and evasive. The fact that the phrase stuck in Jerry’s mind from the elevator encounter also offers further proof that he’s not as superficial as he seems. He remembered it, and now we do too.

Sometimes, though, we may find patterns that a viewer may not have noticed on first pass. That’s one of the appeals of doing analysis. As we get to know the film more intimately, we see patterns of coherence that probably many viewers didn’t notice before. In classically made films, for instance, a scene is likely to start with a long shot, proceed to two-shots or over-the-shoulder framings, and then toward tighter close-ups. This stylistic patterning follows the rising drama of the scene’s action. Most viewers probably don’t notice these patterns, but directors, cinematographers, editors, and film students are more likely to catch them. When we analyze a film’s style, we may be surprised to find how often these “hidden” patterns emerge.

Very occasionally a filmmaker gives us something in between obvious patterns and buried ones. A film might repeat something in such a way that (a) you recognize it as a repetition on first pass but (b) you can’t recall exactly what it harks back to. In other words, the filmmaker deliberately organized the movie so that the things that come back are difficult to place in the film as a whole.

The best-known example is perhaps Last Year at Marienbad, where the drifting, dreamlike succession of scenes doesn’t supply standard plot progression. The result is that the images, music, and lines of dialogue are felt as echoes of earlier scenes, but most viewers can’t pinpoint exactly where they first appeared. Another instance would be Buñuel’s Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie. Here we get scenes that start more or less realistically, and then devolve into absurdity—at which point one of the people in the scene bolts awake in bed. What we’ve just seen is a dream, but we can’t be sure exactly when the dream started because Buñuel and screenwriter Jean-Claude Carrière didn’t supply a scene that shows the character going to bed. One effect is that the movie seems like a daisy-chain of overlapping dreams, with no sure point at which we can declare that this or that moment is real.

Both Marienbad and Discreet Charm rely on a fact of cinema: It unrolls in time. So do novels, of course, in the act of reading anyhow. But when you’re reading a book you can stop and page back to check where you went off-track. Since the arrival of videotape viewing, we can in principle do the same thing, and we’d want to replay moments if we’re undertaking an analysis. But the normal conditions of viewing, in both theatres and at consumer command, bias us toward forward momentum. Intent on what happens next, we have a surprisingly hazy recall of what preceded the scene we’re watching now. Halfway through a movie, try to come up with an accurate scene-by-scene list of what you’ve just watched.

The diffuse memory we have of the prior action, and the difficulty of going back to check, is one reason that films need some explicit patterning, their marked repetitions, their constant restatement of the story’s premises. Redundancy of information compensates for the time-bound nature of viewing. Films that don’t supply this, as in my recent example of Sueño y silencio, demand a second viewing—and risk frustrating audiences.

In another country, at other times

Hong Sang-soo has long been a master of the half-hidden pattern. Each film, usually devoted to the comic deflation of male pretension, is built on a unique armature of repetitions. Most critical commentary simply ignores those, trying to summarize the plots straightforwardly and taking the result as comments on contemporary life—an urban milieu in which intellectuals eat, drink too much, smoke endless cigarettes, and make clumsy attempts at romance and sex. “People tell me that I make films about reality,” Hong remarks. “They’re wrong. I make films based on structures that I have thought up.” It’s the structures, I think, that engage us, and partly by asking us to test our memories of what we saw only an hour or less before.

For instance, The Virgin Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors (2000) at first seems a straightforward he-said/ she-said plot. Initally, scenes showing us a love affair’s progress are organized around one character. Then the affair is replayed, but centering on another character. Many scenes show us each character apart, but when they’re together, that scene gets repeated in the second character’s story. The problem is that some significant details are different in the two versions. We’re asked to wonder whether we’re getting the same story as each character remembers it, or two alternative universes in which the stories differ slightly. Moreover, it’s not easy to recall whether this or that prop or line of dialogue was precisely the same in the first presentation. The strain on our memory is part of the film’s fascination.

Hong has been a regular in the Dragons and Tigers sidebar over the years. He’s reliably prolific: two of his best films, both made in 2010, were in that year’s program. This year brought us another Hong brain-teaser and funnybone-tickler, In Another Country. It’s a measure of Hong’s growing international reputation that Isabelle Huppert is recruited to play three roles in another mazelike plot.

Yonju, staying with her mother in a coastal hotel and beset by family problems, tries writing film scripts. In the first, Anne, a French filmmaker, is vacationing with a South Korean director and his pregnant wife. As Anne gets involved with a hunky, good-natured lifeguard, the director is also making a play for her. Cut back to Yonju, trying another draft. In this one, Anne is a rich housewife from Seoul having an affair with a married man—again a director, but played by a different actor. As she waits for him to join her at the hotel, she meets the same lifeguard and romantic complications ensue. Back to Yonju trying another draft. Now Anne is accompanied by another woman, an older professor. They meet the first director, pregnant wife again in tow, while Anne has become preoccupied with getting life advice from a monk. Once more, needless to say, the lifeguard plays a central role.

As you’d expect with a multiple-draft narrative, the changes are accompanied by some constants—an evening barbeque, the lifeguard emerging from the sea, an encounter between him and Anne in his tent. There are even repeated ellipses, bits that are skipped over in each mini-story. For instance, in all three drafts Yonju, acting as hostess, starts to take Anne on a shopping trip and promises to show her something interesting. But then we cut to Anne alone, wandering through town. Why did the women separate? Is this Anne on a different occasion?

Most to the point of memory tricks, we’ll see something in a late scene that may result from something we saw in an earlier draft. When a bottle of liquor breaks on the beach late in the film, you might remember that a previous scene showed the bottle there already broken—but which scene, in what point, in what story? It’s as if Yonju’s different versions have contaminated one another, with scenes from one draft taken for granted in a different version. In the third draft, what Yonju promised was so interesting seems to be the lighthouse. We may forget that in the earlier versions, we never knew why Anne was searching for the lighthouse. Still, we’re unlikely to forget the parallel framings.

This sort of play with our memory can bring the movie to a satisfying, if enigmatic, conclusion. An umbrella, a casual and forgettable prop in one version, provides a kind of minuscule climax in the last. And the final shot of Anne walking into the distance becomes a variant of the film’s first one.

In Another Country provides plenty of social comedy. Hong’s customary satire of Korean males’ awkward sexual aggressiveness is now accompanied by digs at westerners’ search for mystic Asian enlightenment. But the narrative structure is amusing in itself. Hong cajoles us into enjoying the surprising but inevitable recycling of situations, lines, and camera setups. Few filmmakers can make audiences laugh at the mere appearance of a shot and tease us to expect a replay of or departure from what we’ve already seen. Even if we couldn’t say precisely when we saw that image before, we recognize it and participate in a light-hearted game—the game of form.

Wristcutters share their stories

Romance Joe (2011) was made by Lee Kwangkuk, Hong Sangsoo’s assistant director on many projects. No surprise, then, that his debut relies on parallels and variants. Yet it’s much more explicitly about storytelling than In Another Country. Hong uses Yonju’s script drafts as a peg to hang his variations on, but he doesn’t suggest he’s exploring the very nature of narrating. Lee puts fiction-making at the center of his game.

It would be misleading to summarize the plot, since the film aims to put any firm sense of what really happened into question. The core, we might be tempted to say, is the story of a schoolgirl, Cho-hee, who is shunned because she has had sex with an unnamed man. A boy in her class takes pity on her, and when he finds that she has slashed her wrists in a forest glade, he rescues her. They tentatively fall in love and flee to Seoul. On their first night there, he takes fright and returns home. Left alone, she turns to prostitution, and years later, when the boy is now in Seoul in film school, she agrees to participate in a student film he’s crewing. He doesn’t recognize her. More years pass, and the boy is now a film director. He returns to the village, recalls their runaway romance, and in despair attempts suicide. Meanwhile, Cho-hee’s son, whom she has left with her grandparents, comes to the village in search of his mother.

I think it’s fair to say that even this bare-bones anatomy of Romance Joe isn’t fully registered on a first viewing. And in any case, my synopsis is misleading. Why? Because many of these actions are presented as intersecting tales told by two characters who don’t know one another. A Seoul screenwriter recounts the story of the boy’s search for his mother as a purely fictitious one, an idea he has for a script. Alongside that tale, but not precisely inside it, we see Lee, another writer who’s blocked on a story and visits a village to compose a film. There he spends a long night with a tea lady-hooker, Rei-ji, who takes over storytelling duties. Like Scheherazade, she regales him with another story (see our top still). Her tale focuses on the suicidal screenwriter she calls “Romance Joe”–who turns out to be a filmmaker who has gone missing.

So we have one character telling the story of another character who’s hearing a story presented by Rei-ji–a story about yet a third filmmaker, the despairing director, and one that includes his own memories. More confusingly, Rei-ji’s story not only overlaps with the boy’s quest; she becomes a character in the first screenwriter’s imaginary plot. To add to the intricacy, the film employs only partial framing situations, so we might get a scene establishing one tale’s telling, then the embedded tale, and then another situation of telling, as if what we’ve just seen was launched by one storyteller but picked up by another. Instead of a Chinese-box or Russian-doll structure, with one tale neatly enclosed in another, we get something like a cut-and-shuffle mix. And like In Another Country, this film doesn’t wrap things up by a return to the narrating frame; we’re left with something more ambivalent–a question about the very status of the whole assemblage of stories.

It sounds choppy, but it all flows. As one scene slips into another, with abrupt reminders that we’re seeing events told by someone or other, we’re confronted with a cascade like that in Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie. We’d be unlikely to recall the precise moment when one story melted into another. Storytelling is linked to rumor and gossip, chiefly by the fact that the trigger for Lee’s initial writer’s block is the suicide of a major actress, supposedly hounded by innuendo. The chief parallel is to Cho-hee, driven to suicide by malicious classmates, but other characters sport the scars of slashed wrists. In this context, the motifs of rumor and suicide tie together the stories conjured up by each of the narrators–again, apparently operating in some predetermined harmony.

Throughout, our uncertainty is increased by some tantalizing misdirections. Might Rei-ji, not Cho-yee, actually be the boy’s mother? Has Lee, after hearing Rei-ji’s story, created the very film we have watched? Finally, the possibility that Rei-ji is no less a fictioneer than the professional writers is broached when she returns to the teahouse and tells the younger hooker that you can make more money through talk than through sex. “Everyone wants a different story. Put some thought into what clients want.” In telling one screenwriter a story about another one, she’s just suiting the service to the customer.

When we study narrative we naturally emphasize the main plot points, the twists and climaxes that claim our attention, the hints that pay off: the gun in the first act that goes off in the last. But films like In Another Country and Romance Joe remind us, as Roland Barthes put it, that “reading is forgetting.” By planting items that will become important later, filmmakers keep us focused on what’s to come and eventually mobilize memory to make all the pieces fit. But filmmakers can also seed their plots with small things that we barely register, then bring them back as half-recalled items. Films like Hong’s and Lee’s are more than puzzle movies; they induce our imaginations to grapple with the limited capacity of our memories. Those limitations in turn affect how we judge characters and the truths of the tales they bear. And in films like theirs, as often in life, our judgments have to remain in tense suspension.

I discuss problems of viewers’ memory in “Cognition and Comprehension: Viewing and Forgetting in Mildred Pierce,” in Poetics of Cinema. I consider Jerry Maguire‘s narrative organization in The Way Hollywood Tells It. For previous VIFF entries that examine complex narration and plot structure, go here and here.

P.S. 5 Oct 2012: Sean Axmaker, with whom we spent many lively hours at VIFF, has posted reviews of several Asian films, including Romance Joe, at Parallax View.

In Another Country (2012).