Archive for the 'National cinemas: Africa' Category

The World comes to Vancouver

The Golden Era.

Kristin here:

One of the great pleasures of the Vancouver International Film Festival is the ability it provides for a quick trip around the world, especially to countries whose films are seldom seen in a non-festival setting.

In one day I was able to see an Algerian film and one from the Ivory Coast. It struck me that both of them reflected how far digital filmmaking has come in small producing countries. When digital cameras came on the scene, they were hailed as a way for people in nations with little or no filmmaking infrastructure to create movies. The results, fascinating though they might be, often betrayed visually the fact that they were made with non-professional cameras.

Perhaps we have reached a new stage in digital filmmaking in such countries. Both the Algerian film, The Rooftops (Merzak Allouache, 2013), and the Ivory Coast one, Run (Philippe Lacôte, 2014), have a polish and complexity of form and style that put them on a level with those made in larger, more established national cinemas.

The Rooftops provides a model of how to make a film with a limited budget and avoid conventionality. Allouache chose to set the film entirely on the rooftops of five districts of Algiers. It’s a gimmick of sorts, and yet it carries practical advantages. No sets had to be built, and few, if any scenes required artificial light. Presumably no streets had to be cleared, since no action is staged at ground-level.

Beyond that, each scene could be played out with the city of Algiers providing a backdrop, as when a group of young musicians practice on one of the rooftops:

With backgrounds like that, who needs sets?

The film has a strict formal logic, both spatially and temporally. It begins by introducing five rooftops, each with its own set of characters. There’s no crossover among the groups. None of them ever meet, so this isn’t what David has termed a network narrative. But the look of each rooftop is different, and simply by keeping the characters in one limited area, the filmmakers help us keep track of them fairly easily as the narrative moves among storylines.

The film starts with the first call to prayer in the darkness before dawn, and at intervals the four other calls follow (with a subtitle providing information on the name of each call and the time period within which the respective prayers are supposed to be performed.) These essentially act as chapter breaks, giving a sense of time passing. The five prayers also echo the five rooftops.

There’s no shortage of drama in each group’s story. On a lower floor of an unfinished building a mob boss has a man tortured, trying to force him to sign something. This disturbs a group of filmmakers taking shots from the roof above, with dire consequences. A landlord is murdered on another rooftop, and a suicide occurs on yet another. One gets a cumulative impression of crime and conflict being rife across these various districts of Algiers.

Allouache is considered the preeminent Algierian director, and the violence and strife depicted rather melodramatically are part of his ongoing critique of his nation’s social problems.

In contrast, Lacôte sets Run apart by adopting a classic flashback structure. The film opens with the crisis of the story: the hero, nicknamed “Run,” shoots the prime minister in a crowded auditorium and flees.

From then on, we see him in hiding as he reflects on how he became an assassin. The alternation of scenes from his youth and his current-day attempts to avoid capture are easily comprehensible. Lacôste finds ways to create visual interest and avoid conventional stagings of scenes, as in the low angle above that juxtaposes the hero with a looming, crisscrossing ceiling.

Another example comes when his friend gives him shelter and food. Rather than a simple shot/reverse-shot conversation across a table, we see a depth scene, with Run sitting on the floor to eat and his friend in the foreground twisting to talk with him:

Back in the 1960s and 1970s, the notion was that people in underdeveloped countries could gain small cameras and discover their own ways of making films, free of Hollywood conventions. To some extent that happened. But with the globilization of mass media, few people, however isolated, can remain unaware of Western culture.

Presumably some filmmakers have aspired to match the technical standards of Western offerings in international film festivals. These two films show them succeeding, having thoroughly grasped the conventions of both art films and popular genres. We ‘ll discuss an example of the latter in an upcoming entry on Middle-eastern films at VIFF, and in particular the Iranian vampire film, Girl Walks Home Alone at Night.

Ann Hui’s quiet epic

Ann Hui’s career is usually associated with intimate films, mostly studies of character. We saw her at Ebertfest earlier this year, where she presented A Simple Life, the epitome of such films.

Now she has surprised audiences with another character study, but one set in a tumultuous period of Chinese history, the late 1930s and early 1940s. The Golden Era (2014) tells the story of female writer Xiao Hong, who died young in 1942. Not all the facts of Xiao Hong’s life are known, and the narrative sketches scenes derived from the author’s own writings. Interspersed are “documentary” shots of interviews with people (played by actors) who knew and worked with Xiao Hong.

Much of the tale consists of small-scale scenes, conversations among a few people set indoors or in the streets. Yet as the Japanese invasion begins and spreads, occasional big scenes occur, and Hui proves herself perfectly capable of suggesting creating a sense of epic events.

The war is only fleetingly present, however. We see it mainly from the viewpoint of the main characters, as when a quiet indoor conversation scenes are abruptly and startlingly cut short by bombs going off outside and shattering windows.

The film’s settings and costumes create a vivid sense of the era. There are street scenes in Hong Kong shortly before its fall to the Japanese that appear almost documentary in their realism. Throughout the images are beautiful, as the frame at the top of the entry demonstrates.

The film’s three-hour running length adds to the epic feel, tracing the heroine’s changing fortunes across momentous historical events. It makes a striking contrast with A Simple Life, and yet Hui’s concern with precision and detail in delineating characters remains constant. The pair might bring her back to the sort of prominence outside Hong Kong that she enjoyed in the 1980s and early 1990s. Indeed, The Golden Era was just presented as the gala film at the Busan Film Festival.

Another farewell from a Ghibli master

Just over a year ago Miyazaki Hayao announced that he would retire, having completed and released his final film, The Wind Rises (2013). Speculation over the fate of Studio Ghibli, the animation studio that he co-founded, followed.

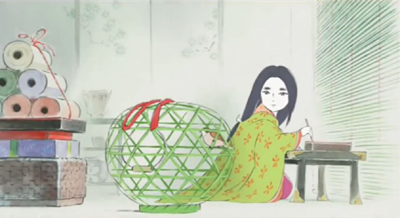

Now we have the reported final film of a second of the three original founders, Takahata Isao, whose most famous film is Grave of the Fireflies (1988). Like The Wind Rises, The Tale of the Princess Kaguya (2014) lets its director go out on a high note.

Based on a tenth-century fairy tale, Princess Kaguya has a distinctive style, with most scenes done in translucent watercolors in pastel shades, quite different from the solid, vivid colors of much of Miyazaki’s work. It tells its story in a leisurely fashion, running 137 minutes, which may be a bit challenging for younger children, but it is never boring.

Kaguya is not necessarily a princess. We’re not sure what she is. She appears miraculously one day as a tiny baby in a glowing bamboo shoot. She is iscovered by a bamboo-cutter who assumes she is a princess and insists on calling her that. The bamboo-cutter and his wife raise her in a forest cottage (seen below). The opening section is idyllic, with the tiny girl growing unnaturally fast, in spurts. She is befriended by neighboring children, and the group explores the surrounding countryside, reveling in the beauty of the plants and animals they observe there.

Spurred by another miraculous discovery, this time of gold nuggets inside a bamboo stalk, the bamboo-cutter decides to build a mansion in a nearby city and make Naguya into a real princess by marrying her off to royalty. There ensues the classic competition among suitors to find the most fabulous object and present it to Naguya.

Naturally Naguya longs for the countryside and finally rebels. In a remarkably stylized, exciting scene that contrasts with the rest of the film, she races toward her forest home, and the pastel settings disappear. She becomes a blur of black, white, and red flashing through a gloomy landscape with sketchily drawn trees and plants that flicker wildly past:

The Tale of Princess Taguya has been announced for an October 17 release in the USA, distributed by GKids. Unfortunately it will only be available in a dubbed version. Even dubbed, it’s worth seeing on the big screen, but with luck there will be an option for the original Japanese-language version with subtitles on the DVD/BD release.

Studio Ghibli has released another film, The Kingdom of Dreams and Madness, a documentary about the studio by Sunada Mami. (It played at Toronto but is not here at VIFF.) Its appearance seems to hint that Ghibli really is going to cease feature production, though the official story is that it is only pausing. It has been a prolific producer of short animated films, and perhaps that side of its activities will continue. For a good summary of the situation and a description of the documentary, see here.

The Tale of Princess Taguya

VIFF: Maps, math, madness, and more

Camille Claudel, 1915.

Kristin here:

We’re halfway through the Vancouver International Film Festival, as we continue to catch up on world cinema in one dizzying ten-day swoop. Here’s a handful of worthwhile films I’ve seen so far.

Another “brave” performance

Critics speak of “brave” performances as those in which the role calls for an actress (seldom, for some reason, an actor) to allow herself to look ugly and awkward or to participate in explicit set scenes. The word got tossed around a lot this year in regard to the two young actresses in Blue Is the Warmest Color, this year’s Palm d’Or winner at Cannes. David and I saw it here and found it disappointingly conventional.

Juliette Binoche’s performance in Bruno Dumont’s Camille Claudel, 1915 (2013) has her eschewing makeup and playing the haggard, aging inmate of an insane asylum. Historically, Claudel was a sculptress and Augut Rodin’s lover before being placed in the asylum by her family. As the title suggests, we see only a small slice of her life, after she has already spent a good deal of time in the asylum, a laudably humane one set in a Catholic nunnery in the mountains.

For much of the film, we stay with her, registering both her annoyance at the antics of her fellow inmates and her compassion for them. She seems to suffer from a persecution complex, cooking all her own food and eating apart from the others (above) through a fear of being poisoned. She attributes her incarceration to Rodin’s and his colleagues’ schemes to steal her studio and sculptures. We have no way of knowing how much of this is true, and hence no way of knowing whether she is really unbalanced enough to be in an institution with incurable cases. Her occasional visits to the complex’s church and her communing with nature help to sustain her.

Well into the film, there is an abrupt point-of-view switch to her brother, the author Paul Claudel, as he pauses en route to the asylum in order to pray. We soon realize that he is a religious zealot, utterly devoted to his own view of Catholicism. The contrast between his dogmatism and Camille’s simple religious sincerity bodes ill for her hopes that he will arrange for her release.

Camille Claudel, 1915 is currently available only on unsubtitled French DVD and Blu-ray.

Math and maps

I am a fan of maps and of scientific exploration of exotic places, and Detlev Buck’s Measuring the World (2012) promised to deal with both in 3D. It weaves together fictionalized accounts of the exploits of two contemporaneous geniuses of the early 19th century: world explorer Alexander von Humboldt and mathematical genius Carl Friedrich Gauss.

I had high hopes for the 3D, imagining scenes a bit like the scene where Michael Fassbender plays with dazzling holograms of space maps in Prometheus–toned down a bit and more scientifically grounded, of course. Unfortunately there was nothing of the sort, with the 3D being used more conventionally for creating depth in the playing space, with branches in the foreground of shots in the Amazonian jungle and that sort of thing.

The film turned out to be a rather rollicking depiction of the two careers. The conceit is set up that Karl Wilhelm Ferdinand, Herzog von Braunschweig provided financing for both Gauss and Humboldt. He is caricatured (above) as a frivolous, silly man who reacts in utter incomprehension when handed Gauss’s first book on mathematics–as who would not at the time, given that it introduced startling new insights that revolutionized the field? Ferdinand was in fact a highly educated military man, and he never supported von Humboldt’s work.

Still, the eccentricities of the two seekers of knowledge are entertaining, the scenes of von Humboldt seeking specimens in the Amazon and on into the Andes are exotic, and the whole thing conveys something of the enthusiasm lingering as the Age of Enlightenment was coming to its end.

Measuring the World is available as a region-coded import with English subtitles under its original title Die Vermessung der Welt on DVD, Blu-ray, and Blu-ray 3D.

An African Charmer

The Senegalese film, Tall as the Baobab Tree (2012), is the first feature of a young white filmmaker, Jeremy Teicher, who first visited the village in which the film is set when he was 19 and making a documentary about it. Based on stories of village life he was told at that time by young students, he made Tall as the Baobab Tree at age 22. The local people helped with the script and acted in the film.

As with many African films, the subject relates to a traditional custom which has come in modern times to be viewed as a problem. It reminds me of Ousmane Sembene’s last feature, Mooladé (2004), which dealt with how a village’s women began to resist the practice of genital mutilation. Tall as the Baobab Tree concerns the practice of selling young daughters into marriage.

The story centers around Coumba, a teenager who has just passed her school exams. Her older brother falls from a baobab tree (the one seen looming above the scene above), and to pay for his medical costs, the father decides to sell Debo, the younger sister, into marriage. Coumba secretly works as a maid in a nearby resort to pay the costs, but although she succeeds in raising most of the money, the local village elder insists that custom dictates that the promised marriage must go through.

Although the father and village elder are clearly seen as in the wrong, they are not made into villains but are seen as stuck in the patterns of outdated traditions. Much emphasis is put on the education that Coumba has benefited from and that Debo will never experience. A touching scene near the film’s beginning shows Coumba among the students waiting in a group as the names of those who have passed their exams are read out. Clearly this was an actual event captured by the filmmaker, and the joy of the successful students effectively emphasizes education as the means to defeat the more oppressive remnants of tribal traditions.

Teicher describes his experiences and approach in collaborating with the villagers on the film in an interview on the BFI website.

Beyond Ghibli

The films of Miyazaki Hayao (Kiki’s Delivery Service, Spirited Away) and his colleagues at the Ghibli animation studio are the heights of Japanese animation. Beyond them, we in the west tend to know of other Japanese animated films as more simply made anime, with lots of violent action. But, as the program notes state, “it’s time to expand your horizons.” Hosoda Mamoru’s Wolf Children (2012) somewhat resembles the Ghibli films in genre, being a fairy-tale-like fantasy set in the present day.

Hana, a student, is attracted to a young man, Ookami, who decides to sit in on one of her classes. She offers to share her textbook, and as a romance develops, she discovers that Ookami is a shape-shifter, able to change into a wolf. After they have two children, Ookami is killed while in his wolf form. His children have inherited his ability, and Hana moves to a house in the countryside to hide their peculiarities from prying eyes.

The story follows the daughter, Yuki, as she decides to go to school and follow the human half of her nature, and the son, Ame, as he prowls the surrounding forests and mountains, communing with wolves he discovers there. The result has an environmental theme similar to that underlying some of Miyazaki’s films, with particular sympathy for the perpetually hunted wolves.

While the figure animation here is not as subtle as that of the Ghibli films, the settings are beautiful and detailed, with highly textured portrayals of the roiling movements of large cumulus clouds and the rustling of countless leaves in a forest.

Wolf Children looks great on the big screen, but if you can’t catch it in a theater, it’s due out in the USA on November 26, available on DVD or a combination Blu-ray/DVD set.

Wolf Children.