Archive for the 'Film theory' Category

Now you see it, now you can’t

DB here:

We usually respond to films spontaneously, but afterward we can think about our responses and figure out why we reacted as we did. When we’re fooled by a mystery, for instance, we can re-watch the film and trace exactly how we were misled. Now that Shutter Island is out on DVD, fans will be dissecting its visual gimmicks. Even when a film isn’t a mystery, a lot of critical analysis involves what we might call a rational reconstruction of how the whole shebang works. Novice screenwriters crack open a movie like The Apartment or The Godfather to peer into the fine mesh of plot construction, to tease out all the setups and plants and twists that seem inevitable only after the fact.

This is film research, we might say, at the personal level. Not in the sense of your or my unique identity, but rather at the scale we see the world. We don’t see atoms or gravity. We evolved to sense and think about middle-sized social and physical phenomena, like places and objects and, especially, other humans. We’re aware of the world because we sense ourselves as individual agents, guided by intentions and desires and beliefs. We’re used to talking about films at this level. When we track action and character, note surroundings and time passing, or ask about the purposes of a plot device or theme, we are working at the level of personhood.

But life assigns us to other levels too. There is the subpersonal level. All kinds of things are happening to you now that you can’t be aware of. You can’t watch the cells in your retina detect this sentence, or the neurons in your brain firing to make sense of it, or the flow of signals to your hand urging the mouse to scroll onward. A huge amount of our mental activity takes place behind the scenes that flit through our consciousness. We can’t pay attention to the man behind the curtain—partly because there is nobody there.

There’s also the suprapersonal level, the level of collective behavior patterns. Now we’re talking about people as parts of large-scale forces, like groups and cultures and societies. Historians have traditionally worked at this level. For example, some researchers have traced how film audiences, en masse, have responded to movies.

More strikingly, many scientists now study “self-organization”—the emergence of patterns of order that don’t seem to be willed or intended by individuals or groups. We find impressive instances in nature: fish swim and birds flock in intricate patterns that no one fish or bird could imagine or dictate. Such self-organization is even more striking in human activities like traffic flow or online networks. Is there a sort of “physics of society”? No doubt people have intentions and quirks, but often we can bracket those out and see shapes in the data that no one could have designed. The classic instance is a power law. A remarkable example is Vilfredo Pareto’s discovery that income distribution in any society tends to settle out as 20 percent of the people controlling 80 percent of the wealth. Mark Buchanan sums up the suprapersonal viewpoint this way: “Think patterns, not people.”

We know we can study films at the personal level. How can we study films subpersonally and suprapersonally too?

Reverse-engineering a movie

Mon Oncle.

My answer comes after four days earlier this month at the annual convention of the Society for Cognitive Studies of the Moving Image. We met in Roanoke, Virigina, in a massive nineteenth-century hotel made over into a convention center. You know the place has things under control when every PowerPoint presentation works flawlessly.

What ideas unite the film scholars, psychologists, and philosophers who gathered here? Roughly, the members explore moving-image media through empirical methods. Empirical inquiry can include classic scientific method (hypothesis/ experiment) or methods of aesthetic, historical or quantitative analysis. Typically the goal is not interpretation of a particular film or TV show or videogame but rather understanding of some general aspects of these media. Not explication, we might say, but rather explanation. Further, most members of the Society are interested in ways that film can be illuminated by areas of modern psychological research, such as neuroscience, cognitive science, and evolutionary psychology.

Some of our philosophers would say that they pursue conceptual analysis rather than empirical inquiry. Still, they join our meetings because the sorts of concepts they want to analyze are the ones that the film folk and the psychologists deploy—concepts like artistic intention or the nature of genre. Many of our liveliest sessions have come from disputes between Filmies, Psychos, and Philosophes.

For more on what we do, I’ve offered some background in earlier entries on this site. I previewed the 2008 convention here and here. I previewed the 2009 convention here and here.

Previews, but not followups. The big problem covering these events is that they’re so busy I have no time to blog during them, and by the time they’re over I’m usually en route to Il Cinema Ritrovato in Bologna. So I tended to make those entries introductions to the cognitive perspective, rather than surveys of who said what. This year, because our gathering was earlier than usual, I’m trying to sum up the event reasonably soon after it ended. We had simultaneous sessions, sometimes three at once, so I attended fewer than half of the talks. I’ll try to mention presentations that seem relevant, even if I didn’t hear them. Similarly, I heard some presentations (e.g., Lisa Broad on possible worlds) that were stimulating but don’t quite fit into my thesis here.

There were plenty of talks that developed arguments at the level I called personal. That is, they analyzed how films were designed to achieve certain effects. This calls for “reverse engineering”: starting from plausible viewer responses and then looking for creative choices made by the filmmakers that seemed to fulfill particular functions.

Take as an example Carl Plantinga’s paper on how we strike up moral attitudes toward characters. He was interested in how we achieve what Murray Smith calls “allegiance”—a “pro-attitude” toward certain characters. Is it just a matter of wishing good things for them, or admiring their positive traits? Is it a matter of sympathy for their situation?

Take as an example Carl Plantinga’s paper on how we strike up moral attitudes toward characters. He was interested in how we achieve what Murray Smith calls “allegiance”—a “pro-attitude” toward certain characters. Is it just a matter of wishing good things for them, or admiring their positive traits? Is it a matter of sympathy for their situation?

Carl argued that all these factors play a role, but they aren’t enough to assure our siding with a character. He argues that allegiance also involves moral judgments, or rather moral intuitions. Films exploit two facts about these moral intuitions: they must be summoned up quickly, without much thought, and they are often driven by emotion rather than ideas.

Oddly enough, our moral intuitions are not necessarily driven by moral standards! Carl drew on Anthony Appiah’s analysis of moral judgments as influenced by how a situation is framed, ordered, and primed—basic cognitive cues that influence responses. For example, Legends of the Fall sets up two brothers, one conventionally moral and the other not. Yet it’s the wild, violent Tristan who earns our sympathies, because he displays vitality, youth, beauty, sensitivity, and closeness to nature. The upshot is that we rationalize a moral judgment on non-moral grounds. Carl got several questions about his conception of morality and the possibility that our moral intuitions are tied to things we value, like beauty.

Malcolm Turvey offered a paper on gags in Jacques Tati. Pointing to prior work on how Tati’s gags are integrated into a shot’s composition (scattered so that we may miss them) and linked to one another (through overlap, Kristin has suggested), Malcolm went on to argue that the gags themselves don’t obey the conventions of classic comedy. They exhibit strategies of misinterpretation, blockage, ellipsis, fragmentation, and concealment that are highly original and unusually challenging. Malcolm is working on a book on “ludic modernism,” and he sees Tati as fitting into this tradition.

Malcolm’s precise and persuasive account was framed by a strong attack on the tendency of cognitive film theory to concentrate on ordinary, even undistinguished films and ignore problematic and avant-garde instances. He pointed to passages in Stephen Pinker’s writings that mock experimental art, and he urged cognitive film researchers to “call Pinker out” for his borderline Philistinism. He remarked that psychological researchers could learn as much from Tati’s work as from ordinary films…and maybe discover new things.

A similar sort of rational reconstruction at the level of personal response was found in many other papers I heard. Jason Gendler dissected the misleading narration in The Blue Gardenia. Rory Kelly wondered why viewers tend to forget the water-utility plotline at the start of Chinatown. James Fiumara considered why modern startle effects are comparatively rare in classic horror films. Torben Grodal isolated a group of “disgust-driven phobic films” (Taxi Driver, Blade Runner, Se7en) that sink so deeply into disgust that melancholy drives out empathy. Lennard Hojberg studied circular camera movements that express the dizziness of love as based on embodied vision.

A similar sort of rational reconstruction at the level of personal response was found in many other papers I heard. Jason Gendler dissected the misleading narration in The Blue Gardenia. Rory Kelly wondered why viewers tend to forget the water-utility plotline at the start of Chinatown. James Fiumara considered why modern startle effects are comparatively rare in classic horror films. Torben Grodal isolated a group of “disgust-driven phobic films” (Taxi Driver, Blade Runner, Se7en) that sink so deeply into disgust that melancholy drives out empathy. Lennard Hojberg studied circular camera movements that express the dizziness of love as based on embodied vision.

Some researchers used quantitative procedures to capture a film’s regularities. Monika Suckfuell (right) exposed some very complex patterns in a short film, Father and Daughter. These create a distinct emotional tone through what she calls “distance editing.” The patterns are combinations of thematic units like problem-solving or humor, and the recurring combinations arouse both comprehension and pleasure. In another quantitative study, Tseng Chiaoi and John Bateman sought to tie concrete uses of filmic elements with more abstract aspects of meaning. (Chiaoi and John had done a presentation on film-based discourse semantics at last year’s event.) Concentrating on characters’ action patterns, Chiaoi used computer software to trace their structures in television commercials and the war genre.

Squeezing the stimulus

Bopping after a session: Tseng Chiaoi and Paul Taberham.

The talks I’ve mentioned, along with several others, analyze processes that we can access by re-viewing films, studying their form and materials, and examining the genres and stylistic traditions to which they belong. But other talks concentrated on the subpersonal areas, the parts of our responses that we can’t access so easily.

For instance, how do we mentally stitch together various shots to create a unified space for a scene’s action? Film scholar Todd Berliner and psychologist Dale Cohen presented an account of how we achieve an illusion of spatial continuity. Initially the brain grasps shots as if they were pieces of space selected by the viewer, and then it builds up a model of the whole space—say a porch in front of a house’s front door. When a character moves his arm a certain way toward an offscreen area, our model of porches and doors makes it most probable that he is pressing the doorbell.

For instance, how do we mentally stitch together various shots to create a unified space for a scene’s action? Film scholar Todd Berliner and psychologist Dale Cohen presented an account of how we achieve an illusion of spatial continuity. Initially the brain grasps shots as if they were pieces of space selected by the viewer, and then it builds up a model of the whole space—say a porch in front of a house’s front door. When a character moves his arm a certain way toward an offscreen area, our model of porches and doors makes it most probable that he is pressing the doorbell.

In such ways we run “beyond the information given.” Filmmakers count on our doing that, so they give us feedback (say, the sound of a doorbell, or a shot of a door opening) that confirms our model of the space. Most mainstream films build in such redundancy. But the unity of these spaces is undermined by some contemporary exhibition technology. Todd and Dale suggested that the mental models we build of space exclude the movie theatre, so that surround sound and 3D become problematic.

They also got several good questions. How concretely specified are these model spaces? How do they develop in the course of a scene? Might our perception of continuity come down to a lack of perception of discontinuity—that is, maybe we operate on very simple default assumptions and don’t build up many models of the space.

Todd and Dale’s presentation was in the Helmholtz tradition; they even invoked “unconscious inference” as part of the story. Another tradition, represented by SCSMI founders Joseph and Barbara Anderson, invokes James J. Gibson’s ecological approach to perception, which argues that such modeling and inference-making isn’t really happening. Things are much more direct: Perception is data-driven, and needs top-down correction only in rare cases (like nighttime or fog).

Other perceptual researchers try for a more parsimonious research strategy: How much information about the visual world can we squeeze out of the stimulus? This question was raised by Jordan DeLong, who has been exploring how we can identify emotional arousal through very “low-level” information. Using a corpus of 150 films (more on this later), he looked at shot lengths, the distribution of shot-lengths across a film, and a purely physical measure of visual activity (essentially the change from frame to frame) to see if they correlate with genres we associate with high levels of arousal, like action and adventure films. Jordan’s study is preliminary, but there is the possibility that certain purely physical features are reliable indices to levels of arousal—even if people don’t notice those features and are much more fastened on characters and their actions.

The current projects of Tim Smith’s research team exemplify the parsimonious strategy. Tim is a long-time participant in SCSMI, and his talks show how a research program can expand and enrich itself.

We know people look at certain areas of a shot. We also know that our attention is directed, driven by features of the stimulus. What features? We filmies would pick out shot composition, color, movement, lighting, shot scale, etc. We can access those middle-level variables through expert introspection and analysis. But can those features be further decomposed?

Tim thinks so. We can consider any of these technical qualities as made up of luminance, color channels, and other low-level physical aspects of vision. Through signal-detection methods, Tim seeks to pinpoint what the crucial variables are. The results of his work are soon to be published, and I don’t want to give the game away. I’ll just say that he has shown through eye-tracking that certain low-level features are more important than others in engaging viewers’ attention.

One implication of Tim’s findings is that what I’ve called “intensified continuity” seems to have an optimal grip on spectators. This technique, he remarked, “almost paralyzes the eyes,” yielding “an illusion of active vision with passive eyes.” More generally, his work seems to back up James Cutting’s remark that “There is no such thing as voluntary attention sustained for more than a few seconds at a time.” Most of our attention is at the mercy of the outside world, which means that filmmakers need to engage us at every moment—either with narrative, or with something else we’ll find arresting.

Dan Levin, Pia Tikka; in the background William Brown, Carl Plantinga, and Dirk Eitzen.

Dan Levin gave the keynote address at SCSMI two years ago, and he showed how we vastly overrate our ability to spot outrageous changes in the world or on the movie screen. (He’ll have a field day with the tricks in Shutter Island, such as the one surmounting this blog.) This time around Dan talked about Theory of Mind in the movies, the ways that films exploit our (species-specific?) inclination to attribute beliefs, desires, and goals to the creatures we see in the world, and in films. His paper scanned mandatory, bottom-up cues, middle-level activity (the sort of organization of visual space Todd and Dale discussed), and then “controlled cognition,” such as our narrative expectations. So for Dan it’s not all in the stimulus. Once we’ve picked out certain aspects of it, our Theory of Mind system locks on them.

What aspects? Chiefly, signals of intention and marked eye direction. When we think we’re watching an intentional agent, like a movie character, we tend to see the agent’s eye direction as giving us a clue to his or her aims. Using films he has made, Dan tests people for how eyeline-matched cuts are read, and he varies the cues to see how people construe them differently.

Interestingly, when he showed the same shots in a different order, about two-thirds of the subjects didn’t notice that the order was different. That is, whether the object of the glance or the person glancing came first, gaze deflection remained the primary cue to understanding the situation. This suggests to me that storytelling cinema doesn’t absolutely need the classic pattern of person looking/ person looked at/ person looking, but the extra shot makes sure we all understand (redundancy again).

A similar sort of top-down/ bottom-up theory was proposed by Dan Barratt, who gave it a more computational spin. Like Tim, he works on eye movements; like Todd and Dale he’s interested in how we construct space; like Dan, he seeks out intentional factors. It’s not all in the stimulus, but we won’t know how much until we keep squeezing.

Ripples in the flow of films

The Society broke new ground in what I called the “suprapersonal” realm, that of large-scale patterns of activity that aren’t explicitly coordinated by individuals or groups. Several researchers are probing this in relation to films. Films are, in effect, deposits of human behavior; they are artifacts resulting from choice. What if we find patterns of choice that we can’t plausibly trace to coordinated decision-making?

Chris Atherton raised the issue by considering how to study style statistically. Citing Barry Salt as a pioneer in the area, he focused on the work of the Cinemetrics group and offered suggestions on how to better collect data and track patterns at various levels of generality. More sharply, he posed the question of function. How can you measure that? One implication was that in a big body of films we can disclose order that can’t wholly be explained as the sum of individual choices. Those choices matter, but so do forces we have yet to determine, including historical processes. Chris’s reflections chimed nicely with those of our keynote speaker.

James E. Cutting is a distinguished perceptual psychologist at Cornell. He’s written a fine book on motion perception and has done a quantitative historical study of the creation of the canon of French Impressionist painting. He’s a former dancer and a sensitive appreciator of art and music (and film). He’s the ideal person to analyze ticklish aesthetic issues.

You may have run across him recently because his research on Hollywood films was picked up and trumpeted in the press. “Solved: The Mathematics of the Hollywood Blockbuster,” read one headline. Needless to say, James was doing something more subtle. You can read summaries here and here.

In his lively address, “Attention, Intensity, and the Evolution of Hollywood Film,” James explained two of his areas of interest: the ebb and flow of change across a film, and how that change is tied to human pickup. James studies these topics with a big database: 150 movies from 1935 to 2005. He emphasizes widely seen films belonging to five genres and chosen from the highest-rated titles on IMDB. But there’s a micro- side too. He and his research team went through every film frame by frame coding each one along many dimensions.

Naturally, he takes on the vexed issue of Average Shot Length. You can read the ongoing discussions of this concept on Yuri Tsivian’s Cinemetrics site. What interests James is less ASL in itself than the ways in which comparable patterns of shot lengths cluster in certain parts of the film. A film’s ASL may be 8 seconds, but in some passages several shots might have similar lengths, say 12 seconds each. Moreover, those patterns may “ripple through the film,” recurring at certain intervals and different scales (shot clusters, scenes, or other chunks).

Not every film shows such patterns; film noirs seem random in their patterns of shot lengths. But many movies, especially those of the last fifty years do display these patterns—typically clusters of short shots for physical action, clusters of longer ones for conversations. This clustering tendency is on the increase, even outside the action genre.

Not every film shows such patterns; film noirs seem random in their patterns of shot lengths. But many movies, especially those of the last fifty years do display these patterns—typically clusters of short shots for physical action, clusters of longer ones for conversations. This clustering tendency is on the increase, even outside the action genre.

The finding leads James to ask about the pacing of visual change, which raises the prospect of the sort of tension/ release dynamics we find in music. The patterns he finds don’t look arbitrary because they match the so-called 1/f or pink-noise pattern. This pattern has been detected in the natural world, in heartbeats, and in brain activity. It’s also been discovered in reaction times to tasks. In effect, the 1/f pattern captures not continual attentiveness but rather an alternation of intense concentration, moments of slower pickup, and moments of sheer mind-wandering. A nontechnical explanation of the 1/f pattern is here; a technical one is here.

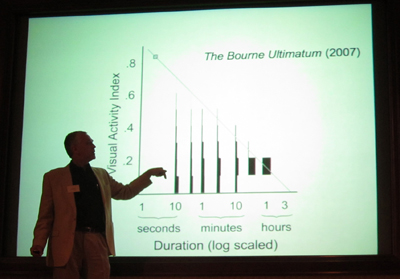

As for intensity, James is seeking to measure visual activity in the shots. How much change, in effect, can there be from frame to frame? This can be captured by correlating each frame with its mates. James and his team find that from 1930 to 1950, there’s been a steady increase of frame-to-frame visual activity across all genres. The images became busier, with more movement. Today, he suggests, Hollywood is exploring ways to raise the frame-to-frame visual activity—not only through lots of movement of characters (the action film comes to mind) but also through “queasicam” handheld movements.

In combination with decreasing ASLs, Hollywood seems to be asking: How briefly can I show you this and still get the point across? So far, James suggests, films like Mission: Impossible III and The Bourne Ultimatum seem to be the busiest at the visual level. But animated films score about the same.

James has a caveat: The size of the screen matters. Even a big home-theatre screen doesn’t duplicate the breadth of a theatre screen, which activates not only our central vision but our peripheral vision too. That’s why bumpy shots that you can tolerate on a computer monitor may make you queasy at the multiplex. Interestingly, the Bourne films and Cloverfield, James suggests, were more popular on IMDB after the DVD versions came out. Perhaps people were better able to assimilate them on a smaller display.

At one level, James is interested in the subpersonal factors. He grants that you don’t notice cuts but can attend to them if you shift your focus from the story. But the widespread patterns he discloses aren’t easy to ascribe to deliberate planning. Nobody but an avant-gardist would decide to have shots of similar lengths at points 14 minutes or 25 minutes apart throughout the film. But James finds such correlations at levels beyond chance.

I can’t pretend to understand everything mathematical in James’ argument, but I think that his discoveries open up a new way to think about pacing in film. My first impulse is to think about historical causes, as Chris suggests: filmmakers learning from each other, converging on optimum choices. But I also like to entertain the possibility that this optimum carries a resonance even beyond the flux of history. Perhaps like fish and fowl, filmmakers are obeying and viewers are fulfilling, completely unawares, deep rhythms built into nature and numbers.

A tangled databank

Traditional humanists would decry a lot of what goes on at SCSMI meetings. The appeal to general explanations, the recourse to biology and evolution, the use of quantitative and experimental methods would all smack of “scientism.” But more and more, humanists are starting to turn away from the endless reinterpretation of canonical or non-canonical artworks. Many are also quietly defecting from the Big Theory that dominated the 80s and 90s. In film publishing, I’m told, editors have come to an informal moratorium on books on Deleuze. Possibly more people write them than read them.

Committed to a theory of permanent revolution in Theory, humanists are seeking new pastures. Some have discovered neuroscience, others evolutionary psychology. Franco Moretti has launched quantitative studies of the literary marketplace. For many converts, the reconciliation with science is just a bandwagon to hop onto, and they will jump off when a newer one trundles past. But other scholars have been committed from early on. The prospect of “consilience,” the compatibility between the sciences and the arts, is something the literary Darwinists like Brian Boyd, Jonathan Gottschall, Joseph Carroll, and like-minded souls were defending long before it became fashionable.

Film theory, as Joe Anderson is fond of pointing out, has a long and intense fascination with experimental psychology. Hugo Münsterberg, Rudolf Arnheim, and Sergei Eisenstein saw no conflict in studying film art with tools and findings derived from the sciences. That interest was lost in the 1960s, for a variety of reasons. But some of us have persisted. An explicitly “cognitive” perspective has been developing in film studies for the last twenty-five years, and SCSMI has nurtured this tradition since 1997. Our commitment is deep. We’re making headway. We’re not going to go away.

There is grandeur in this view of life, and cinema.

Our Society owes a great debt to Stephen Prince of the Virginia Tech School of Performing Arts and Cinema, who hosted this year’s convention. He also gave a splendid paper on the research traditions behind precinematic optical toys, as a way of thinking about modern CGI.

I found these books on suprapersonal patterns helpful: Mark Buchanan, The Social Atom: Why the Rich Get Richer, Cheats Get Caught and Your Neighbor Usually Looks Like You (London: Cyan, 2007); Steven Strogatz, Synch: The Emerging Science of Spontaneous Order (New York: Theia, 2003); Philip Ball, Critical Mass: How One Thing Leads to Another (New York: Farrar Straus Giroux, 2004).

Todd Berliner and Dale Cohen’s paper, “The Illusion of Continuity: Active Perception and the Classical Editing System,” is scheduled for publication in the Journal of Film and Video in 2011. Tim Smith’s paper is in press at Cognitive Computation as P. J. Mital, T. J. Smith, R. Hill, and J. M. Henderson, “Clustering of gaze during dynamic scene viewing is predicted by motion.” You can check Tim’s DIEM project for video demonstrations, and his blog, Continuity Boy.

The original article by James Cutting, Jordan DeLong, and Christine Nothelfer, “Attention and the Evolution of Hollywood Film,” appeared in the March issue of Psychological Science. Access is through subscription.

As for Shutter Island, thanks to Justin Daering for pointing out the double sleight-of-hand. More thoughts on the film and Scorsese’s expressionist/ impressionist tendencies are in our backfile.

1999 Conference of the Center [later Society] for Cognitive Studies of the Moving Image; Valby, Denmark. Photo by Johannes Riis.

Glancing backward, mostly at critics

DB bere:

As Freud’s mom says in Huston’s film, “Memory plays queer tricks, Siggy.” Herewith, some journeys into the past, launched on a lazy June afternoon.

Ten-best lists are nothing new. The New York Times ran them in the 1930s. Here’s one for 1940 (NYT 29 Dec 1940, p. X5).

The Grapes of Wrath, The Baker’s Wife, Rebecca, Our Town, The Mortal Storm, Pride and Prejudice, The Great McGinty, The Long Voyage Home, The Great Dictator, and Fantasia.

The author’s runner-up titles include Of Mice and Men and The Philadelphia Story. Pretty tasteful by today’s standards, no? Who came up with a list including Hitchcock, Borzage, Sturges, Pagnol, Chaplin, Disney, Milestone, Cukor, and Ford twice?

None other than Bosley Crowther, long-serving Times reviewer who became the emblem of middlebrow taste in endless polemics (including some I’ve mounted). Who knew he was a closet auteurist?

Winchester ’73 (1950).

Now try this one.

The movies live on children from the ages of ten to nineteen, who go steadily and frequently and almost automatically to the pictures; from the age of twenty to twenty-five people still go, but less often; after thirty, the audience begins to vanish from the movie houses. Checks made by different researchers at different times and places turn up minor variations in percentages; but it works out that between the ages of thirty and fifty, more than half of the men and women in the Unites States, steady patrons of the movies in their earlier years, do not bother to see more than one picture a month; after fifty, more than half see virtually no pictures at all.

This is the ultimate, essential, overriding fact about the movies. . . .

Yes, another oldie, this time from Gilbert Seldes’ book The Great Audience (1950). What we’ve been told for years was characteristic of our Now—the infantilization of the audience—has been in force for at least sixty years.

By the way, here are some US features released in 1950: Father of the Bride, Gun Crazy, House by the River, In a Lonely Place, Julius Caesar, Mystery Street, Night and the City, Panic in the Streets, Rio Grande, Shakedown, Stage Fright, Stars in My Crown, Summer Stock, Sunset Blvd., The Asphalt Jungle, The Baron of Arizona, The File on Thelma Jordan, The Furies, The Gunfighter, The Third Man, Twelve O’Clock High, Union Station, Wagon Master, Where the Sidewalk Ends, Whirlpool, Winchester ’73, and probably some other good movies I haven’t seen.

Perhaps not a luminous year, but I’d settle. Especially compared with 2010. Did kids just have better taste then?

Beyond reviewing

Most people conceive a film critic as a film reviewer. The review is a well-established genre, and we all have its conventions in our bones. At a minimum, you synopsize the plot, comment on the acting, mention the pacing or the cinematography, throw in some wisecracks, and recommend or condemn the film. Good reviewers do these things well, but the genre remains a limited one.

Crowther was a reviewer; Seldes was something more. But how to define that extra something? Two long-lived heavyweights can help us.

In the 1935 essay “The Literary Worker’s Polonius: A Brief Guide for Authors and Editors,” Edmund Wilson spells out what he takes to be the duties and genres of literary labor. At the time, the “New Criticism” in the universities had barely gotten started, so most literary criticism Wilson encountered was journalistic and belletristic—that is, reviewing.

Accordingly, Wilson distinguishes different types of reviewers. There the people who simply need work. There are literary columnists who pump out observations on the latest books. There are people who want to write about something else; that’s when you use the book under review as a pretext to ride your hobby horse. There are the reviewer experts, as when a philosopher is called in to review a book of philosophy. Then there’s the rarest, the “reviewer critics.” Here is why such creatures are rare.

Such a reviewer should be more or less familiar, or ready to familiarize himself, with the past work of every important writer he deals with and be able to write about an author’s new book in the light of his general development and intention. He should also be able to see the author in relation to the national literature as a whole and the national literature in relation to other literatures. But this means a great deal of work, and it presupposes a certain amount of training.

In sum, the best critic has to be very, very knowledgeable. But is knowledge enough?

T. S. Eliot, it’s often said, believed that the only qualification of a critic is to be very intelligent. (One example of this claim is here.) What Eliot actually wrote is more interesting. His 1920 essay “The Perfect Critic” is considering Aristotle as a theorist of literature. Of The Poetics he notes:

In his short and broken treatise he provides an eternal example—not of laws, or even of method, for there is no method except to be very intelligent, but of intelligence itself swiftly operating the analysis of sensation to the point of principle and definition.

The final clause is a good description of what I take “poetics” to be as applied to film. We analyze effect (“sensation”) so to discover not laws but principles (governing a genre, a trend, a style, whatever) that we in turn articulate (“definition”). In this analysis, we don’t use a method—that is, I take it, a prior commitment to a system of thought that blocks our seeing the object in its own terms.

Contrary to the common modern view that our personal feelings and ideas color everything we think about, Eliot seems to advocate a more objective way of thinking. Aristotle the theorist is praised because “in every sphere he looked solely and steadfastly at the object.” His search for the principles underlying tragedy, comedy, and epic is contrasted with the dogmas of Horace, the “lazy critic” who offers us precepts, tips from the top about laws to be obeyed. (Sound familiar from screenplay manuals?)

Aristotle, Eliot thinks, was endowed with “universal intelligence”: “He could apply his intelligence to anything.” Such a gift overrides the sort of specialized inquiry that yields “methods.” I read “The Perfect Critic” as recommending that critics try to combine their sensitivity to nuance with Aristotelian intelligence:

Aristotle had what is called the scientific mind—a mind which, as it is rarely found among scientists except in fragments, might better be called the intelligent mind. For there is no other intelligence than this, and in so far as artists and men of letters are intelligent (we may doubt whether the level of intelligence among men of letters is as high as among men of science) their intelligence is of this kind.

This is what it is to be “intelligent” in Eliot’s sense: to be wide-ranging, rigorous, and committed to understanding the artwork both as unique object and embodiment of principle. He finally spells it out in his praise for the Symbolist Remy de Gourmont:

Of all modern critics, perhaps Remy de Gourmont had most of the general intelligence of Aristotle. An amateur, though an excessively able amateur, in physiology, he combines to a remarkable degree sensitiveness, erudition, sense of fact and sense of history, and generalizing power.

So Wilsonian erudition and historical knowledge aren’t enough. You need sensitivity, “a sense of fact,” and “generalizing power”—the ability to see larger implications and principles at work in what you’re writing about. In short, the best critics don’t shy away from probing ideas.

The general go

Where do the ruminations of Wilson and Eliot leave us with writers who go beyond reviewing? Let’s go back to Seldes.

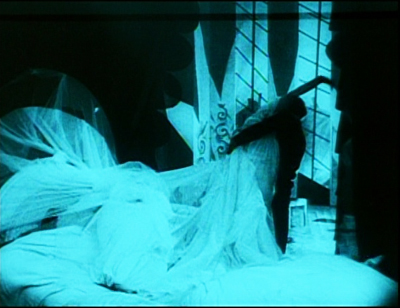

He became one of our best American critics, in fact one of our first media critics, thanks to his “generalizing power.” The 7 Lively Arts (1924) was a trailblazing defense of Tin Pan Alley, comic strips, vaudeville, jazz, and films. Reacting against “genteel” taste, Seldes believed that the bursts of exaltation to be found in the “minor” arts were as profound as anything to be found elsewhere. “Our experience of perfection is so limited that even when it occurs in a secondary field we hail its coming.” Such perfection is to be found, he says, in an instant in The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, when Cesare seizes Jane and the bed curtains snag her gown. He starts with what Eliot called “sensation,” the piercing arousal.

A moment comes when everything is exactly right, and you have an occurrence—it may be something exquisite or something unnamably gross; there is in it an ecstasy which sets it apart from everything else.

But Seldes goes beyond noting moments that give him a buzz. He tries to explain how and why the vulgar arts can arouse us. It’s hard for us now to realize that what we take for granted as vital popular culture was scorned by the much of the intelligentsia. In 1924 Seldes set out on a crusade to convince his readers that the Keystone Kops, Flo Ziegfeld, Irving Berlin, ragtime, and Fanny Brice offered more of genuine artistry than the Bogus Arts (we’d say middlebrow) that were then ruling high culture. In 1924, this was a thunderbolt:

The daily comic strip of George Herriman (Krazy Kat) is easily the most amusing and fantastic and satisfactory work of art produced in America today.

If the best critics offer not only opinions but information and ideas to back them up, The 7 Lively Arts had both in abundance. Seldes begins the book with the suggestion that the consolidation of the film industry, and particularly the establishment of Triangle, Kay-Bee, and Keystone, was the turning-point in the history of American film. But instead of the usual litany of praise for Griffith’s and Ince’s discovery of “cinematic” storytelling, Seldes condemns them as too quickly seduced by extravagant spectacle. The journeyman Mack Sennett stuck to making “the most despised, and by all odds the most interesting, films produced in America. . . . He is the Keystone the builders rejected.” Far more than the work of Griffith and Ince, Sennett’s comedies exploit what cinema is best suited for: chases, crashes, explosions, “locomotives running wild, yet never destroying the cars they so miraculously send spinning before them. . . . And all of this is done with the camera, through action presented to the eye.”

Seldes wrote about radio, dancing, and other pastimes, but films were his special love. An Hour with the Movies and the Talkies (1929) and The Movies Come from America (1937) combine historical knowledge with subtle appreciation of the forces operating on studio picturemaking. These books thrum with ideas. For instance, Seldes defends the director as the key creative artist in cinema. One reason is that only the director can control pacing.

The director is responsible for the general go of a picture, for making it run off neatly, for controlling the speed of its various parts, for seeing that a romantic episode does not race along while a melodramatic conversation lags. He is, or ought to be, responsible for the interruptions of the main action of the picture so that a comic interlude is not placed too near to the climax of a tragic one, but only near enough to give more intensity to the emotion.

What about the camera? Hollywood movies, he says, have developed a rapid-turnover tradition that favors conciseness and novelty in the flow of images.

When Van Dyke in 1934 [in The Thin Man] wished to show a familiar event in the life of any man who walks a dog—an event which, although familiar, might not be passed by the censors—he merely showed the leash tightening and the hand of the man being jerked back; then the man stood still and a little later the same operation was repeated. . . . The part not only takes the place of the whole, but is more effective because the imagination of the spectator supplies what is missing.

Seldes might have added that once we’ve supplied that missing piece, we laugh at Asta’s ability to puncture Nick Charles’ serious disquisition on murder.

Seldes became a tamer thinker later in life. By the 1950s he was part of the media establishment, producing television shows on culture. He grew disappointed with the film industry, leading to his critiques in The Great Audience. Still, his critical skills persisted. His next major book, The Public Arts (1956), pins his hopes on television but also offers a balanced account of Hollywood’s widescreen revolution. Confronted with CinemaScope and its kindred systems, he worried, again, about pacing.

Wherever the movie touches time, it as mysterious and primordial as the beating of the heart. Absorbed in new techniques, directors may neglect essentials as they did a generation ago when they immobilized the camera to favor the microphone; but, as they recovered mobility then, so I am confident that they will recover the art of using and manipulating time in the substructure of their pictures.

Although he’s seldom discussed in film circles now, Seldes stands out as a worthy critic not because of one-off reviews but in virtue of his pointed, sometimes daring ideas, his knowledge, and the zest they arouse in the reader. These are the payoffs, I think, when a critic leaves reviewing, even the 10-best lists and other fun parts, behind.

My quotations from Seldes come from The Great Audience (New York: Viking Press, 1950), 12; The 7 Lively Arts (Mineoloa, NY: Dover, 2001), 204, 309, and 5; Movies for the Millions (London: Batsford, 1937), 75; The Public Arts (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1956), 55-56. For more on Seldes and his milieu, see Michael Kammen’s excellent intellectual biography, The Lively Arts: Gilbert Seldes and the Transformation of Cultural Criticism in the United States (New York: Oxford University Press, 1996).

My quotation from “The Literary Worker’s Polonius,” comes from Edmund Wilson, Literary Essays and Reviews of the 1920s and 1930s (New York: Library of America, 2007), 490.

Although the terminology is different, Eliot seems to be advancing something similar to Kristin’s arguments about film analysis in the first chapter of Breaking the Glass Armor: Neoformalist Film Analysis (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1988).

The Thin Man (1934). Seldes forgot that it was Nora, not Nick, who senses Asta’s response to the call of nature.

A hundred years, plus a few thousand more, in a day

Charlie Keil, Yuri Tsivian, Henry Jenkins, Kristin Thompson, and Janet Staiger. Photo by Joel Ninmann.

Last Saturday we held the symposium “Movies, Media, and Methods” in honor of Kristin’s arrival at age sixty. Four distinguished scholars, all professors from major universities, presented top-flight talks. As a bonus, Kristin gave The Film People a glimpse into her Egyptological work. I report on this very full day in the hope of giving a sense of how stimulating we found it.

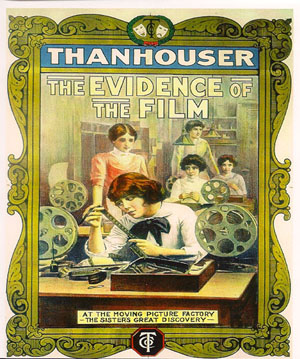

Thanhouser was an American film company that flourished between 1909 and 1917. It has been overshadowed by Biograph because that firm put out more films and, not incidentally, employed D. W. Griffith. But Ned Thanhouser has been diligently gathering his family company’s output from archives around the world and releasing it in informative DVD editions. The most famous Thanhouser production is probably Cry of the Children (1912), a powerful attack on child labor. You could also try the thriller The Woman in White (1917), adapted from Wilkie Collins’ masterful novel. A study in sadism, and more subtle than The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo.

Charlie Keil, an expert in 1910s US film from the University of Toronto, examined Thanhouser’s films with two questions in mind. Did the studio have a “distinctive personality” in its products? And does its output reflect the development of film style across the crucial transitional years of the early 1910s? Borrowing a method that Kristin had applied to Vitagraph films in an essay, Charlie took one film from 1911, one from 1912, and one from 1913. Charlie wasn’t ready to conclude that these specimens displayed a unique studio style, but it was clear that across just three years, big changes in storytelling were taking place.

The plot of Get Rich Quick (1911) involves a man who joins a business that is scamming innocent investors. The film uses only five locales and plays scenes in long takes. The Little Girl Next Door (1912) has a more complex plot, with two distinct lines of action that converge on a child’s drowning. It uses many more locales and an ellipsis of a year to trace the changes in a family’s fortunes. It also incorporates cut-in close views and point-of-view editing. The Elusive Diamond (1913) is less psychology-driven than The Little Girl Next Door, but its intrigue relies almost completely on dialogue titles and it includes many close-ups and variation of camera setups.

Three films and three years: A vivid cross-section of the rapid development of what soon became classical visual storytelling. Moving from 18 shots to 53 shots to 74 shots, the films became less dependent on staging and more dependent on editing. At the same time, Charlie didn’t fail to notice how the long takes in Get Rich Quick allow some felicities of performance, particularly the way that the wife’s handling of her apron charts her psychological states. She brushes it aside to show how poor they are, then she uses it as a giant hankie.

Like all good papers, Charlie’s left a lot to be discussed. People asked about how much pre-planning was done at Thanhouser, about the directors and screenwriters on staff, about the division of labor. We were left with a sense that here was another mostly unknown region that would reward further study.

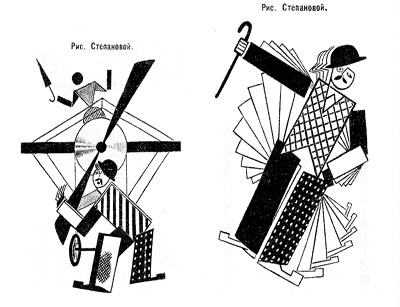

Fernand Léger, Cubist Charlot (1923).

Yuri Tsivian of the University of Chicago carried us into the twenties with an in-depth examination of early Russian reactions to Charlie Chaplin. The paper held many surprises. Chaplin was popular in many countries from 1915 onward, and very soon after he was celebrated by European intellectuals. But Russia lagged behind; there’s no concrete evidence that any Chaplin films were shown there until 1922. Yet the Soviet avant-garde embraced him. How and why?

Instead of looking for a dual relationship—Chaplin directly influencing Russian artists—Yuri postulated a “triangular” relationship, in which Chaplin’s image was mediated through other European sources. For instance, Léger’s numerous images of a fragmented Chaplin led Futurists and Constructivists to declare Charlie “one of us.” They loved the idea of man as a machine executing precisely articulated movement, and what they heard of Chaplin’s pantomime and gags led them to praise him. Chaplin, said Lev Kuleshov, is “our first teacher” because he knows bio-mechanical premises better than anyone. According to the photographer and graphic designer Rodchenko Chaplin instructs viewers in how to walk or put on a hat in the most perfect manner.

So strong was this “virtual” image that artists could read Chaplin into the slapstick comedians they did see. Yuri showed that Varvara Stepanova’s striking rendition of Chaplin as an airplane propeller derived from a film he wasn’t in!

Perhaps she didn’t care: Nikolai Foregger suggested that Chaplin himself was unimportant, that the crucial fact was that he created a whole school of comedians within what Yuri called “a collaborative research community”—that is, Hollywood!

Yuri’s paper, in homage to the Russian Formalists, invoked the “law of fortuity” in art. This refers to the possibility that artistic borrowings, blendings, and crossovers are not determined by any broader social processes, as the Marxists were arguing, but are merely contingent. “Life interferes with art from below.” Accidents and unforeseen intersections, such as the Chaplin craze meeting the Constructivist movement, allow artists to seize on whatever is around them for new material. Yuri’s reference was to Kristin’s revival of Formalist methods in her “neoformalist” studies of Eisenstein, Tati, and other filmmakers.

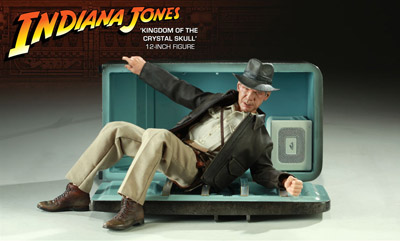

Janet Staiger of the University of Texas at Austin collaborated with us on The Classical Hollywood Cinema, and she has for several years been the leading scholar of reception studies in film and television. In looking at the Indiana Jones series, her paper nodded to Kristin’s work on the Lord of the Rings franchise and her study of fans’ responses to the films.

“Nuking the fridge,” Janet explained, has become fan jargon for an outrageous plot twist. The phrase comes from a notorious moment in Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull (2008), in which Professor Jones escapes an atomic blast by diving into a lead-lined refrigerator. The moment becomes a crux for clashing fan judgments: This is totally unrealistic vs. Realism doesn’t matter. Janet went on to show how these and other fan responses, entwined in IMDB commentary threads, utilized several different interpretive frames.

One was authorship. Like academics and journalists, fan are auteurists. They assign the director responsibility for major aspects of the film. But this doesn’t mean that they agree in how to use this frame. In the case of Crystal Skull, a certain Kid Mogul asked if Spielberg’s willingness to reinvigorate the franchise was purely mercenary: “Is it just about the money?” Others took a more career-survey approach, noting that after prestige pictures like Schindler’s List Spielberg recalibrated his popcorn movies, particularly by handling violence more gingerly.

Another frame was story-based “lit talk.” Fans disparaging the film found it clumsily plotted and lacking in character development. Several were quite sensitive to narrative coherence, one-off gags (such as nuking the fridge), and pacing. Those defending the film appealed to the emotional burst of the final chase scenes.

Janet’s third frame of reference was what she called “formula dissonance.” She sought to capture what seeing the film would be like for those who knew Indy’s story only through the TV series or video versions of the earlier installments in the franchise. She suggested that the formula was by 2008 quite abstracted and idealized for many fans. Their sense of the franchise was thus tested by the extraterrestrial twist that resolved the Crystal Skull plot. Does it reframe the whole series in a cosmic context, or is it a violation of the premises of the Indy universe?

Janet’s survey of these types of responses made me notice that the assumptions of academic film studies and of journalistic criticism overlap with fan conversation. Fans who liked the film tried to make everything fit by appeal to organic unity, technical proficiency, emotional intensity, and other familiar criteria. It made me suspect yet another reason why “amateur” and “professional” film criticism seem to be merging: Perhaps their conceptual frames of reference aren’t so far apart. But their tastes and their degrees of commitment surely are.

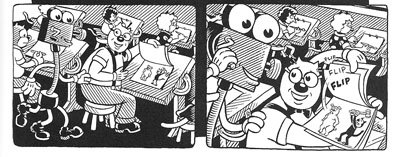

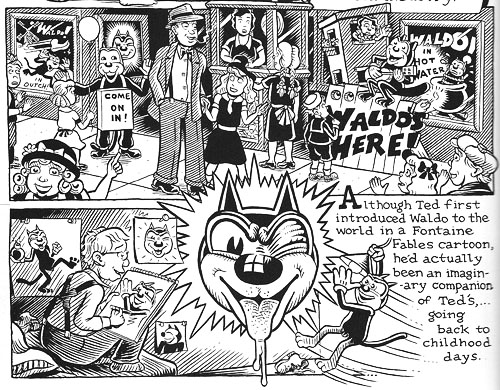

You might have expected Henry Jenkins of the Annenberg School at the University of Southern California to talk about fans too. After all, he practically invented the modern study of media fandom with his book Textual Poachers, and his work influenced Kristin’s study of fan promotion of The Lord of the Rings. Instead he turned to a survey of an artist’s oeuvre. He showed how Kim Deitch’s vast output of stories appropriate imagery from nineteenth and twentieth century mass media and present highly personal versions of the history of popular culture.

In a way, though, Henry’s talk involved fandom because Deitch is himself a prototypical fanman. He’s an obsessive collector, likely to turn his search for a rare toy or drawing into a Byzantine odyssey on the page. Fascinated by Hollywood scandal, he has constructed a phantasmagoric history of mass media through fictional characters (e.g., fake movie stars) who confront real people (e.g., Fatty Arbuckle). He’s particularly concerned about what he takes to be the warping of animated film by the influences of the mass market, epitomized by the Disney empire. The emblematic moment in Boulevard of Broken Dreams comes when Deitch’s Winsor McKay stand-in addresses torpid animators at a tribute dinner and denounces them for selling out.

Deitch’s most famous character is Waldo the cat, and Henry traced the powerful connotations of this emblematic figure. Waldo recalls Felix, the most heavily merchandised comics figure before Mickey, as well as the black cat as a figure of deception, witchcraft, and even African-American minstrelsy. Through Waldo, Deitch could hop across the history of film and comics, from McKay to Mighty Mouse and 1940s abstract films. In Alias the Cat!, Deitch finds in the 1910s everything that we associate with media today: serial narrative, stories shifting across different media platforms, an uncertain line between publicity and self-expression, and a mixing of news and sensational fiction.

Henry situated Deitch in a broader trend of comic artists trying to find a new history of their medium, one that dislodges superheroes from a central role. Deitch’s themes of old-fashioned craftsmanship, lovably antiquated technology, adult dread and degeneracy lurking behind children’s stories, and the commodity demands of comic art link him to contemporaries like Chris Ware and Art Spigelman.

Henry’s talk spurred a lot of discussion, including the question of whether we can treat an artist as offering a history that is comparable to academic research. Can Deitch’s hallucinatory vision of American media be a plausible basis for understanding what really happened? On the whole we don’t expect an artist to offer rigorous arguments. An artwork appropriates history for its own end. (Not all the Greek philosophers actually gathered together in the way Raphael depicts them in the School of Athens painting.) How cogent you find Deitch’s critique probably also depends on whether you share his disdain for Disney. His floppy-limbed denizens fuse headcomix grotesquerie with the 1930s animation that most prestige studios abandoned. As in Sally Cruikshank’s sprightly cartoon Quasi at the Quackadero, Deitch’s rubbery frames revive a style in which everything seems to throb and shimmy.

Kristin’s talk, “How I Spend My Winter Vacations: The Amarna Statuary Project and Techniques of Visual Analysis,” had two parts. In the second part, she reviewed her recent work in assembling statues out of tiny bits that had been dumped by archaeologists decades ago. You can read some of this story here. The side of her work most intriguing to students of film, I think, involves her attraction to Egyptian art in the first place.

Egyptian art is often thought of as unrealistic, but during his reign in the fourteenth century BCE the pharaoh Akhenaten introduced a peculiar sort of stylization into it. When he instituted a monotheistic religion centered on the sun god Ra (embodied in the Aten), he also demanded a new pictorial style. Thus the Aten is depicted as a disc shedding rays, a symbol of life and dominion. In addition, the royal family displays biggish hips and thighs, which fit the fecundity theme. More strikingly to our eye, Akhenaten’s family were represented as somewhat distorted, with long and narrow faces, hands, and feet. The ruler’s crown is elongated as well. Several aspects of the new style are present in Kristin’s favorite scene, a beautiful relief carving known as the Berlin family stela.

You can see the Aten’s rays ending in little hands holding ankh signs to the royal couple’s noses. But just as important is the human dimension of the scene, and two sorts of action displayed there: swiveled shoulders and pointing hands.

Unlike the flat, frontal portrayal we associate with Egyptian art, the family members are caught in twisting postures that bring one shoulder forward. Kristin explained:

Akhenaten is lifting his daughter, his foreground arm moving backward to hold her legs, the other moving forward to support her body as he kisses her. She reaches with her rear arm to chuck him affectionately under the chin, while her other arm moves backward in a pointing gesture. On the opposite site, Nefertiti’s foreground arm is held bent and backward to steady the youngest daughter of the three present, who is standing on her thigh and reaching up rather precariously to grab a golden decoration hanging from her mother’s crown. Nefertiti’s rear hand goes forward to steady the second daughter, who is also pointing, this time with her rear arm as she twists to look at her mother. These kinds of gestures can be found again and again in such scenes.

The twisting movement wasn’t unknown among images of workers and private individuals; Amarna artists, presumably encouraged by Akhenaten, applied the device to portraying the royal family.

Just as significant are the pointing gestures we find in the stela. Some scholars have interpreted them as protective gestures, which are found in other images. But Kristin points out:

In those cases, the protecting figures hold their arms straight, they stare in the direction of the thing to be protected (as one presumably would in reciting a spell), and there is something dangerous present. None of this applies in the scene in the stela.

In those cases, the protecting figures hold their arms straight, they stare in the direction of the thing to be protected (as one presumably would in reciting a spell), and there is something dangerous present. None of this applies in the scene in the stela.

After pondering this scene quite a lot, it occurred to me that it looked like a really early film, a short scene, perhaps 30 seconds long, that we were to interpret as a tiny narrative. The pointing gestures seemed comparable to pantomime, where one has to interpret movements in the absence of intertitles.

Given that so much Amarna art is about displaying the royal couple as having created life by giving birth to their daughters and as sustaining that life, it seems to me that this stela is full of indications of nurturing. The columns and roof indicate that the parents have their kids in a little shelter to keep them out of the hot sun. The rows of pots behind Akhenaten’s stool are no doubt filled with cool drinks for them. Nefertiti carefully holds onto the two children on her lap while Akhenaten kisses the eldest. My interpretation is that the eldest is saying something like, why don’t you kiss sister, too?” and the one opposite is pointing out the kiss to her mother and saying something like, “Look, daddy’s kissing sister; I want a kiss too.”

This may not sound like the sort of thing kids would say, but the circulation of affectionate gestures among the family members in these casual scenes is nearly universal. The chucking under the chin gesture used by Meretaten here shows up again and again, as do embraces and kisses.

Despite all the stylization, then, Kristin concludes that the stela depicts a scene of intimate affection, complete with a child toying with a mother’s ornament. This homely realism chimes with other realistic tendencies in Amarna art, such as the differentiation of right and left feet and the presentation of plants and animals in non-stereotyped ways. In sum, Kristin’s ability to look closely at film style helped her make discoveries about visual narrative in a completely different domain.

So our Saturday talks included cinema-related material from 1911 to about 2010, and with Kristin’s lecture we flashed back about 3300 years. Every talk was crisp and lucid. We were spared the juggling of empty abstractions, the free-associative rambling, and the self-congratulatory cleverness that plague the humanities. We got knowledge and opinion presented with enthusiasm, modesty, and good humor.

Kristin and I are grateful to our presenters, as well to all the friends old and new who showed up: Leslie Midkiff Debauche from Stevens Point, Carl Plantinga from Michigan, Peter Rist from Montreal, Brenda Benthien from Cleveland, Virginia Wright Wexman from Chicago, Vicente José Benet from Spain (via Chicago) and many others. In all, a day to remember.

For more information on Kristin’s research see my earlier entry. For other cinematic implications of the Berlin stela of Akhenaten’s family , see Kristin’s blog entry here. Her article, “Frontal Shoulders in Amarna Royal Reliefs: Solutions to an Aesthetic Problem,” is available in The Journal of the Society for the Study of Egyptian Antiquities 27 (1997, published 2000).

All of our speakers are represented on the Web: Henry here, Charlie here, Janet here, and Yuri here (and of course on Cinemetrics). For more on Janet’s study of online critics and the frames they inherit, see her essay, “The Revenge of the Film Education Movement.”

Kim Deitch, Boulevard of Broken Dreams.

METROPOLIS unbound

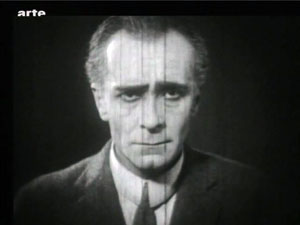

Fritz Lang has created a lot of pretty pictures and has discovered the astonishing talent of Brigitte Helm. I cannot blame him for not being able to cut the quantity of ideas in individual scenes mercilessly enough (the water catastrophe, the duel), but instead repeatedly trying out new lighting and angles. This time the film’s qualities lie precisely in these efforts: and if the viewer knows how to make the best of something, he will derive pleasure from these images.

Rudolf Arnheim, review of Metropolis, 1927.

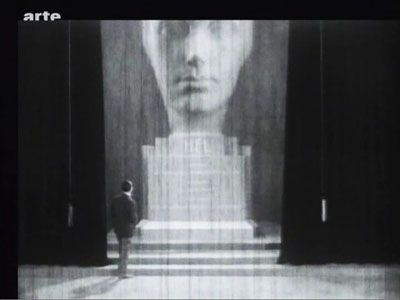

Along with La Roue and The Battleship Potemkin, Metropolis (1927) is one of the great sacred monsters of the cinema. Many versions circulate, and restorations never seem to stop. A beautifully restored, though incomplete, version was premiered in Berlin in 2001. This is the basis of the most authoritative DVD releases. By now, however, everybody has heard about the 2008 discovery of a significantly longer version in Argentina, a 16mm preservation copy drawn from a scratch-infested 35 nitrate original.

Since 2008 a team at the Friedrich-Wilhelm-Murnau-Stiftung has been at work adding material from the Argentine version to the earlier one. Kristin and I have written earlier entries (here and here) tracing the progress of the restoration, and the team have produced a detailed website explaining their work. The result made its world premiere at the Berlin Film Festival earlier this year, and an exhaustive exhibition about the film has been running at the Deutsche Kinematek in Berlin.

Now I’ve seen it, at a screening during the Hong Kong International Film Festival. Frank Strobel, a member of the restoration team, conducted the Hong Kong Sinfonietta, and another collaborator, Martin Koerber, curator at the Deutsche Kinematek, was present to discuss the restoration process. A handsome booklet, cosponsored by the Goethe-Institut of Hong Kong, provided a lot of background. The film was projected digitally, but at very high resolution and looking quite crisp. I had a front-row center seat. I had a swell time.

Metropolis has never been my favorite Lang of the period, but this version makes the strongest possible case for the film. It’s hard to dislike its shameless, preposterous ambitions, its stew of biblical and modern ingredients, its bold architectural vistas, and its trancelike characterizations. Also, people running crazily about in gargantuan spaces can usually hold your interest.

I just met a girl named Maria

All [the American editors] were trying to do was to bring out the real thought that was manifestly back of the production and which the Germans had simply “muffed.” I am willing to wager that “Metropolis” as it is seen at the Rialto now is nearer Fritz Lang’s idea than the version he himself released in Germany. . . . There was originally a very beautiful statue of a woman’s head, and on the base was her name–and that name was “Hel.” Now the German word for “hell” is “hoelle” so they were quite innocent of the fact that this name would create a guffaw in an English speaking audience. So it was necessary to cut this beautiful bit out of the picture . . . .

Randolph Bartlett, The New York Times, 13 March 1927

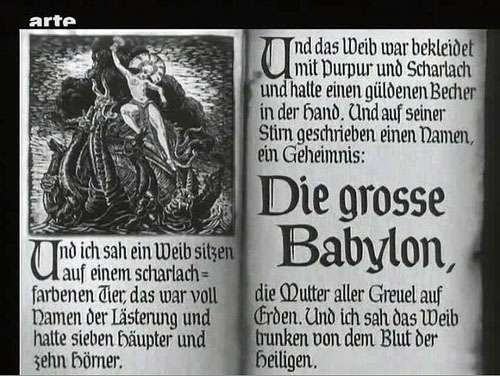

The new version gives the film a better narrative balance. Somewhat surprisingly, the plot hinges on one of the oldest and simplest narrative devices: mistaken identities. The overlord Fredersen engages the crazed scientist Rotwang to create a mechanical Maria who will lead the workers astray. Rotwang takes the occasion to avenge himself on Fredersen by having his robot urge the workers to destroy the machines. Two Marias, then–actually more, if you count the robot Maria’s incarnation as the Whore of Babylon in the Yoshiwara Club.

Thanks to the Argentine footage, we now know that another major character doubling involves Freder. At the start of the version we all know, Freder is visited by Maria and a flock of children. Upon seeing her radiant charity, he becomes suddenly convinced that he must join the oppressed workers, his “brothers and sisters.” Helping them has become his destiny. He gains an ally in Josaphat, an employee whom his father has brusquely fired. Descending to the cavernous machine halls, Freder switches identities with Georgy, a worker who returns aboveground to live Freder’s life. Freder wants him to go to Josaphat’s apartment, where they will meet. But the Thin Man, a long, leering hireling of Freder’s father, is charged with trailing Freder.

Stretches of the Thin Man subplot are missing from the previous version, but now we can see that Georgy/ Freder is a sort of early counterweight to the Maria/ Maria parallels. As in the latter case, the switch leads to misunderstanding, with the Thin Man following Georgy to the club and eventually to Josaphat. The Georgy substitution also allows Harbou and Lang to introduce the Yoshiwara Club early, but teasingly, in a rapidly dissolving montage. Only later will we get a good look at the delicious degeneracy inside.

As Martin Koerber indicated in several remarks, the older, most common version of Metropolis turns it into a science-fiction film, since it puts the robot Maria at the center of the plot. Just as important, though, is Freder’s plan for overturning class oppression, something fleshed out in the Georgy/ Josaphat material. Other new footage puts the relationship between Fredersen and Rotwang in a new light. We now see that Rotwang was in love with Fredersen’s wife Hel, and he has constructed not only a huge bust of her but also a “mechanical man,” outfitted with a distinctly female anatomy, as a sort of Hel substitute.

Fredersen diverts Rotwang’s plan to the purpose of mimicking Maria. So we get another doubling: Freder’s mother Hel becomes the firmware for the robot Maria through the machinations of two father figures. (Freder will kill one and redeem the other.) In all, the new footage yields a play of eerie Freudian substitutions.

The 2010 restoration also establishes the film as consisting of three large-scale movements. The first section, “Prelude” (Auftakt), runs a bit more than an hour. It shows Freder joining the workers and his father planning to have the Thin Man follow him. This part also introduces Rotwang, establishes Fredersen’s order to make a robot Maria, and ends with Rotwang’s capture of Maria. A second part, called “Intermezzo” and lasting about thirty minutes, is devoted to intertwining the Freder/ Josaphat plot with the creation of the robot Maria. The section more or less climaxes with a demo of the new Maria, dancing sexily at the Yoshiwara.

In “Furioso,” everything builds to a climax across a remarkable fifty minutes. The cloned Maria leads the workers to destroy the machines, fulfilling Rotwang’s plan to avenge himself on Fredersen, while the real Maria escapes from Rotwang’s compound during a fight between Rotwang and Fredersen. (We’re still lacking some of this footage.) At the same time, Freder and Josaphat converge on the underground city. The workers’ smashing of the machines triggers a flood from which the children must be saved. At the finale, during a hand-to-hand struggle with Freder, Rotwang falls to his death. There follows the famous epilogue in which Freder, “the Mediator,” must bring together hands (the foreman Grot) and head (the capitalist Fredersen).

Fluidity and freedom

This delirious fable is rendered with unrelenting zest. Lang has now perfected his breathless version of silent-film narration. He relies on simple, immediately graspable compositions, rapid crosscutting among different plotlines, and a dynamic approach to analytical editing.

In the late 1920s, many American films became more heavily dependent on intertitles; it’s as if directors were anticipating talkies. But of Metropolis’s over 1800 shots, I counted only 26 expository titles and 156 dialogue titles—in a film running nearly 2 ½ hours. Lang plunges us into each scene with no fuss, and once we’re there, a smooth continuity carries us from shot to shot. Confronting the seven deadly sins in the cathedral, Freder turns away, twisting Georgy’s cap in his hands as he exits the frame.

Cut to the main area of the cathedral, and Freder is still twisting the cap as he enters the frame. (Like other shots from the Argentine version, this is slightly reduced because of the 16mm source.)

He lifts the cap, and we get his point of view on Georgy’s name and number.

Cut to the Yoshiwara nightclub closing, as Georgy steps groggily into the street.

Here the new footage lets us see that Lang is exploiting the sort of verbal and imagistic hooks he had developed in earlier films: from Georgy’s cap to Georgy himself, with no need of an intertitle to take us to the new scene.

Lang’s freedom of camera position is typical of late silent cinema, but he deploys his angles with characteristic precision. As usual in Europe, Hollywood-style continuity isn’t completely adhered to—there are some crossings of the 180-degree line—but Lang is careful to keep us oriented to the action through eyelines. This allows great flexibility in camera placement.

Fredersen is dictating to his secretaries while Josaphat is monitoring prices. A vast establishing shot shows all of them.

Fredersen’s pacing around his office allows Lang to introduce a new area around the window and the desk.

Now pacing in the center of the office, Fredersen pauses in his dictation and Freder bursts in behind him.

But Fredersen, who’s already holding up one hand as he speaks, simply twists his wrist, and this silences his son.

The shot approximates Freder’s point of view, but Lang gets a bonus from it. The sharp change of angle makes the imperious hand (and not, say, Fredersen’s expression) the compositional focus of the shot. In fact, this sort of hovering hand will become part of the characterization of Fredersen, and Lang will stress it through, once more, energetic changes of angle.

And still later, the framing will spotlight Freder’s pointing finger by pushing it to one zone on the far right of the shot.

Lang’s concise handling of such small actions forms a delicate counterbalance to the mass movements elsewhere in the film. Perhaps for him, both gestures and crowd scenes are merely two ways of creating a geometry that can activate every area of the screen.

The carefully controlled freedom of spatial construction is facilitated by one of Lang’s favorite tactics: shooting from directly on the axis of character interaction. (No, Wes Anderson didn’t invent this.) Lang in effect sets the camera between the two characters so that they stare out at us, as if mesmerized. The technique is most memorable in the scene in which Freder is confronted by Maria and the children.

Again, though, the Argentine material brings more instances to our attention.

Putting the camera on the axis allows Lang leeway in changing his angles. From a shot on the center line, you can cut to pretty much any other area of space.

Lang’s crisp visual narration comes to a climax in the well-named Furioso section. As the action ramps up, the characters rush from spot to spot, hurling themselves into the frame and then abruptly halting to hold the composition.

The extreme case is the robot Maria, whose head and limbs jerk puppetlike from one position to another.

In all, Lang’s precise, almost diagrammatic visual style rushes us through the film’s wild plot and dazzling architecture. An emblem of precision in the service of slightly demented material might be that memorable close-up of the robot Maria: One eye staring out normally, the other half-closed, and the mouth half-twisted in a leer, as if the circuitry in the skull was failing.

A little encyclopedia

Martin Kroeber, Togichi Akira, Winnie Fu, Sam Ho, and Wong Ain-ling discuss preservation and restoration at the Hong Kong Film Archive.

In a Q & A after the screening, Martin Koerber and Frank Strobel shared information about the version. They and their colleague Anke Wilkening could publish a whole book about the restoration, but here are some highlights, drawn as well from Martin’s comments at a lengthy seminar at the Hong Kong Film Archive.

*Sources for information about the premiere version include a copy of the script (helpfully marked with reel ends and calculations about running time), censorship cards recording the credits and intertitles reel by reel, Gottfried Huppertz’s musical score, and thousands of production stills.

*Using these materials, earlier researchers were able to create a sort of mosaic of the version that premiered in Berlin in January 1927. The resulting study film embedded long swathes of blank footage as place-holders. The fact that the Argentine shots fitted in neatly proved the validity of that edition. This study film may be ordered on DVD at nominal cost by educational and research institutions.

*What’s still missing? Some shots in the Argentine version may have been censored; we’re missing a bit in which Georgy, at liberty in a cab, sees a woman baring her body. Also lacking is nearly all the fight between Rotwang and Fredersen, which enables Maria’s escape. In addition, the Argentine print lacks a scene showing a monk preaching in the cathedral, which yields some apocalyptic images.

*If the film plays fast for contemporary tastes, don’t blame the restorers. This version runs at 24 frames per second. Actually, for the 1927 premiere the film was run even faster. The score includes passages accompanying missing footage as well as over a thousand synch-points for specific onscreen action. On the basis of this evidence, it seems that the film was designed to run at about 28 frames per second. This reminds us that silent-film running speeds were far from standardized, and they sometimes exceeded the 24 fps that would be established for sound film. (For more on this matter, go here and scroll down a bit.) In addition, Frank mentioned that in theatres with orchestras, the conductor could regulate the speed of the film with a dial set into the podium.

*Why insert the cropped 16mm footage in such obvious fashion? Couldn’t the framelines be adjusted to match the surrounding 35mm material? Yes, but this slight blowup of the footage would falsify the shot scale of the original footage and not match comparable shots in the 35mm footage. Moreover, Martin pointed out that because not all the scratches and fuzziness of the 16mm material could be purged, it’s better to let these stand stand out somewhat as evidence of the vagaries of film history–like leaving some damage visible in historic buildings.

*Why is the restoration in black and white, since most silent film restorations are in color? Lang was opposed to tinting and toning, so Metropolis premiered in black and white. This caused a debate among critics, some of whom considered it a promising departure from contemporary practices of coloring scenes. The tinted versions that one can occasionally see are likely export versions colored at the request of distributors in particular markets.

*Although future screenings of the 2010 version are to be accompanied by other ensembles devising their own music, there’s a powerful case for retaining Huppertz’s original score. It reflects the filmmakers’ intentions, and its Wagnerian romanticism and modern rhythms are enjoyable simply as music. Just as important, Huppertz designed his score around leitmotifs that, as in opera, can call to mind characters who aren’t onscreen at the moment.

*Metropolis, Martin argued, is too often considered simply a late Expressionist film or an early science-fiction effort. Now we can see that it’s much more: “a compendium of everything in the air in 1927 Germany.” It brings together political ideas, debates about class society and urban life, current trends in the fine arts, acting styles, and cinematic experiments. It owes a great deal to the “monumental” films of the late 1910s, such as Joe May’s Herrin der Welt (1919), but it’s also a synthesis of what filmmaking had become since then. “It’s a little encyclopedia of 1927 cinema. . . . There’s something in it for everybody.”

To see the restoration with the stirring score, vigorously conducted by Frank, was a high point of my Hong Kong trip and indeed of my filmgoing year.

This version of Metropolis was simulcast, if that’s the right word, on 12 February by Arte during the premiere at the Berlin International Film Festival. My frames are taken from that broadcast version; hence the bug. The restoration will be screened on Turner Classic Movies in the fall, and then released on DVD in the US by Kino International.

The epigraph quotation from Arnheim comes from Film Essays and Criticism, trans. Brenda Benthien (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1997), 119. The article about the US cut of the film, which became widely seen around the world, is Randolph Bartlett, “German Film Revision Upheld as Needed Here,” New York Times (13 March 1927), X3.