Archive for the 'Film comments' Category

C is for Cine-discoveries

Funuke, Show Some Love, You Losers!

DB here:

Kristin and I think of Brussels as a gray city—gray skies, gray pavements, gray buildings, even gray, if often fashionable, clothes. It isn’t usually a fair description, though. In the twenty-plus summers we have been visiting, many days have been bright. I suppose our impression comes chiefly from one rainy fall we spent here in 1984, on a Fulbright research grant. Still, the public monuments bear us out, especially the Palais de Justice: except for its gold dome, it is gray, and has been encased in gray scaffolding for as long as we can remember.

Indeed, Brusselians assure us that the scaffolding will never go away because it’s holding the Palais up.

The gray motif continues this summer; during my visit, there have been almost no sunny days, just rain and chill. To prove that Belgians have stayed loyal to their favorite color, I took a shot of a new piece of public architecture near the Central Station: a half-circle of tipped-over pyramids that are, ineluctably, gray.

Still, the movies provide my light and color. I talked about Brussels as one of the great film cities in last year’s entry. I found further proof in a 2003 Marc Crunelle’s Histoire des cinemas bruxellois (in a series announced here), a small book with some fine pictures, one of which you will find at the end of this entry.

As usual, my host was the Royal Film Archive of Belgium. The archive offices remain in their splendid old building, the Hotel Ravenstein, but the new museum complex is still under construction. So the screenings continue to be held in the ex-Shell building, a piece of postwar Europopuluxe that I seem to enjoy more than most of the locals.

During my days, I watch films (very, very slowly) in the archive vaults; more about that project in my next entry. At night the event was Cinédécouvertes, the annual festival of new films that don’t yet have Belgian distribution. That festival, going back decades, has now been attached to a bigger event, the Brussels European Film Festival, which this year began on 28 June. BEFF showed thirty new titles, plus eight older items in open-air screenings, and it gave several prizes.

Kristin and I were in Bologna for Il Cinema Ritrovato and so I missed all of these, including the big Flemish film of 2007, Ben X. But Cinédécouvertes, running on during the BEFF, had its second and final week while I was in town. Films screened were competing for a 10,000-euro prize to be awarded to a distributor that would pick up the film. In addition, the venerable L’Age d’or prize would be awarded to a film that maintained the spirit of Buñuel’s scandalous masterpiece.

Herewith some notes on what I saw, and the prize results. Of course on the day I posted this, the sun came out.

Women, prep school, and manga

Cargo 200.

The two Iranian films in the program were earnest but varying in quality. Unfinished Stories (Pourya Azabayjani) is a network narrative following three women across a single night. A suicidal teenager doesn’t return home; her path crosses with that of a wife cast out by her husband; and she in turn brushes past a young woman who tries to smuggle her newborn baby out of the hospital. The situations are engagingly melodramatic, but the links among them (a footloose soldier, a compassionate taxi driver, an enigmatic old man) seemed to me forced, and as is often the case in these tales, the problem is how to conclude each story line in a satisfying way. The use of sound was very fresh, however. I especially liked the teenager’s obsessive replaying of taped conversations with her boyfriend. Often these “auditory flashbacks” are played over a black screen, and they come to exist as discrete, almost virtual scenes.

I like it when a film begins with a sharp, defining gesture, and Three Women (Manijeh Hekmat) had one. In close-up a car drives up to a tollbooth and the driver’s hand tosses a cellphone into a Charity Box there. Someone is on the run and cutting ties, but we won’t find out more for some time.

The first stretch of the movie concentrates on Minoo, a divorced professor and expert in Persian textiles. A rug dealer has promised to keep a precious carpet in the care of her museum, but he changes his mind and tries to sell it. In a fit of temper she grabs the carpet from its owner and takes it to her car, where her somewhat senile mother waits patiently for a trip to the hospital. Then the old lady vanishes. The emphasis shifts to Minoo’s daughter Pegah, who has set out on her own. The maddening Tehran traffic of the early scenes gives way to the empty quiet of the countryside. In the second half of the film, a favorite theme of Iranian cinema—the urban intellectual confronting rural life—is played out vividly when village elders debate whether to stone a woman who has had an abortion.

Like many of the best Iranian films, Three Women tells its story with dramatic force, offering robust conflicts and a degree of suspense rare in arthouse fare. Manijeh Hekmat, who made her name with Women’s Prison, manages the story threads skilfully, creating a continuous revelation of backstory and hints about how the tale will develop. I especially liked the way Minoo gradually realizes that she has had no idea how her daughter is living. As Alissa Simon points out in her perceptive review, Hekmat can spare time for a subtle composition as well. The ending came as a quiet surprise, deflating some dramatic issues but emphasizing the comparative unimportance of carpets, cellphones, and pop music in the face of the deeper problems facing Iranian women.

Add another woman and you have Adoor Gopalakrishnan’s Four Women. The quartet of stories, all adapted from literature and evidently set in the 1940s and 1950s, shows the fates befalling women in different roles, each identified with a title: The Prostitute, the Virgin, the Housewife, and the Spinster. Not much fun to serve in any of them, it turns out. The film has a sharp eye for details of local life and ceremonies, an ambition helped by the high-definition format: a slow-moving river is off-puttingly scummy. A little didactic and schematic, but it’s enlivened by a long sequence of a husband who methodically and endlessly eats everything put in front of him, with a seriousness he cannot bring to his marriage. The sequence starts in bemusement, moves to humor, and persists to the threshold of nausea.

The Argentine La sangre brota (Pablo Fendrik) was a little reminiscent of City of God in its relentless handheld assault on your senses, with the camera grazing faces and people racing in pursuit of drugs and money, with a beleagured taxi driver trying to do the right thing. La maison jaune (Amor Hakkar), from Algeria, appealed more to me. How much we owe neorealism! Quietly and simply, Hakkar tells of a father learning of his son’s death, fetching the body home for burial, and then trying to find a way to relieve his wife’s grief. So he paints his house yellow. Quiet and moving and not as simple, in story or pictorial technique, as it might sound.

Antonio Campos’ Afterschool (US) is a very assured first feature about drug-overdose deaths in a prep school. The story is told almost completely through the consciousness of Rob, an introspective and awkward freshman who indulges in internet porn. Passive to the point of inertia, Rob remains largely a mystery. This effect is often due to Campos’ bold use of the 2.40 widescreen frame, which often excludes some of the most important dramatic information. People are split by the left or right edge, or are decapitated by the top frameline, so we must strain to listen to the conversation and catch glimpses of the characters. This may sound arbitrary, but Campos finds ways to motivate the lopped-off compositions. One shot, when the parents of dead students record their thoughts on video, is one of the strongest pieces of staging I’ve seen this year. Unlikely to get U. S. theatrical release, if only because of its pacing, Afterschool marks Campos as definitely a director to watch. It won one of the two top Cinédécouvertes prizes.

The other top prizewinner was Yoshida Daihachi’s Funuke, Show Some Love, You Losers! It’s another insane Japanese family movie—that is, the family is insane, and the movie acts the same way, out of sympathy or contagion. After the parents are killed trying to save a cat from an oncoming truck (nice overhead shot of bloody skid marks), a new household takes shape. There’s the phlegmatic brother Shinji, his maniacally cheerful wife, his adolescent sister Kyomi, and his sister Sumika, who comes to stay after failing to make it in Tokyo as an actress. Family secrets emerge. Sumika starts turning tricks and Kyomi draws violent manga inspired by Sumika’s adventures. The comedy turns blacker when Kyomi’s comic books become best-sellers and all the family problems regale the reading public. With some scenes shot in high-contrast video, as if they were TV episodes, and a climax that blends film and manga, panel by panel, the film’s style is as all over the map as the characters and their complexes. Good dirty fun from the title onward.

The L’Age d’or prize went, deservedly, to Cargo 200 from Russia. Another black comedy, but one that gets blacker and less funny as it goes along, it becomes sort of a post-Glasnost’ Last House on the Left. (Seriously, maybe there’s an influence of Saw and Hostel here, with hints of Faulkner’s Sanctuary.) Set in 1984 and stuffed with retro clothes, hairstyles, and music, the plot spins crazy-eights around the corpse of a returning Afghan war hero; a teenager trying to buy homebrew vodka; a bootlegger who keeps a Vietnamese refugee as an assistant; a small-town policeman with a penchant for voyeuristic sex; and a professor of dialectical materialism who wanders, blinking, in and out of the lurid plot twists. Director Alexei Balabanov, who did the pioneering rough genre picture Brother (1997), gives no quarter here.

Strength in simplicity

Albert Serra directs the three kings in El cant dels ocells.

My three favorites were all resolutely unfancy. Shultes, a Russian item by Bakur Bakuradze, is a minimalist study of a pickpocket. Shultes lives with his mother, gives some of his loot to his legit brother, and takes up with a boy whom he tutors in thievery. At slightly over 200 shots, the movie is staged, shot, and cut with a precision that reminded me of Apichatpong Weerasethakul (Syndromes and a Century). On the inexpressiveness scale, Shultes, with eyes and mouth too small to fill up much of his face, makes Bresson’s pickpocket look positively other-directed.

As with all movies about stealing, the pleasure lies in trying to figure out the plan and spot the telltale moves—sort of like the misdirection of a magic act. Here the drama is cunningly contrived. What is Shultes writing in his little brown book? Who is Vasya? What’s his big plan? The plot jumps a level when we realize that all we’ve seen is a flashback, and the ensuing conversation puts things in a startling perspective. Our blankly amoral protagonist even becomes a shade sympathetic. Too rigorous and unemphatic to be an arthouse import, I fear, but ideal for a festival.

As with all movies about stealing, the pleasure lies in trying to figure out the plan and spot the telltale moves—sort of like the misdirection of a magic act. Here the drama is cunningly contrived. What is Shultes writing in his little brown book? Who is Vasya? What’s his big plan? The plot jumps a level when we realize that all we’ve seen is a flashback, and the ensuing conversation puts things in a startling perspective. Our blankly amoral protagonist even becomes a shade sympathetic. Too rigorous and unemphatic to be an arthouse import, I fear, but ideal for a festival.

Shinji Aoyama is best known for Eureka (2000), which won a prize at an earlier Cinédécouvertes. Sad Vacation is one of those films that try to do justice to the ways in which humans become tangled in relationships based on acquaintance, momentary bits of kindness, and sheer chance. Kenji helps smuggle Chinese workers into Japan, but when one dies, Kenji takes the orphan boy under his wing. Soon characters and connections proliferate. There is the salariman and his dumb pal searching for the runaway Kozue. Kenji cares for a slightly daft girl, and he becomes romantically involved with the bargirl Saeko. Accidentally he finds the mother who deserted him, and he joins her new family, complete with mild-mannered father and rebellious brother. Always hovering around are several men and women who work for the father’s trucking company—people rescued, it’s implied, from crime or neglect.

Aoyama manages the crisscrossing relationships delicately, without losing sight of the fact that behind Kenji’s laid-back appearance is a boiling desire to avenge himself on his mother. But she’s his match. A woman of smiling serenity, or smugness, she seems infinitely resilient. The final confrontation of the two, in a prison visiting room, has the giddy sense of one-upmanship of the prison visit in Secret Sunshine. Things turn grim and bleak, yet Sad Vacation manages to feel optimistic without being sentimental; even a flagrantly unrealistic soap bubble at the close seems perfectly in place. I notice that Aoyama has made nearly a film a year since Eureka; why aren’t we (by which I mean, I) seeing them?

Aoyama manages the crisscrossing relationships delicately, without losing sight of the fact that behind Kenji’s laid-back appearance is a boiling desire to avenge himself on his mother. But she’s his match. A woman of smiling serenity, or smugness, she seems infinitely resilient. The final confrontation of the two, in a prison visiting room, has the giddy sense of one-upmanship of the prison visit in Secret Sunshine. Things turn grim and bleak, yet Sad Vacation manages to feel optimistic without being sentimental; even a flagrantly unrealistic soap bubble at the close seems perfectly in place. I notice that Aoyama has made nearly a film a year since Eureka; why aren’t we (by which I mean, I) seeing them?

Some films, like those of Angelopoulos, seem to spit in the face of video. You can’t say you’ve seen them if you haven’t seen them on the big screen. Such was the case with my favorite of the films, The Song of the Birds (El cant dels ocells, 2008) by the Catalan director Albert Serra. It merges an aesthetic out of Straub/ Huillet—black and white, very long static takes, drifts and wisps of action—with a joyous naivete recalling Rossellini’s Little Flowers of St. Francis. Serra’s film also reminded me of Alain Cuny’s L’Annonce fait à Marie (1991) and one of the greatest of biblical films, From the Manger to the Cross (1912). All make modest simplicity their supreme concern.

We three kings of Orient are . . . well, definitely not riding on camels. We are in fact trudging through all kinds of terrain, scrub forests and watery plains and endless desert, to visit the baby Jesus. We are also quarreling about what direction to go, whether to turn back, and why we have to sleep side by side so tightly that our arms go numb. And in an eight-minute take we are struggling up a sand dune, vanishing down the other side, and then staggering up again in the distance.

The three kings aren’t characterized, and they are sometimes unidentifiable in the long-shot framings; only their body contours help pick them out. Intercut with their non-misadventures are glimpses of an angel (whom they may not see) and stretches featuring Joseph and Mary, who caress a lamb. Eventually the infant Himself puts in an appearance, burbling. When the kings finally arrive, one prostrates himself. The image settles into a tidy, unpretentious classical composition and we hear the film’s first burst of music, Pablo Casals’ cello rendering of the folk tune Song of the Birds.

The kings get a chance to bathe in a scummy pool before returning home. Off they trudge. “We’re like slaves!” one complains. In a final shot that would be sheer murk on a DVD, they swap robes and set off in different directions. Did I see them embrace one another? Did they murmur something? I couldn’t tell for sure. Night was falling and they were far away.

Like Casals’ cantata El Pessebre, The Song of the Birds gives us a Catalan nativity. The simplicity is genuine, not faux-naif, and the humility doesn’t preclude humor. Although the shots are quite complex, the spare surface texture invests a familiar story with a plain, shining dignity. Discovering films like this, which you will never see in a theatre and could not bear to watch on video, makes this ambitious festival such a worthy event. It maintains the heritage of one of the world’s great cinema cities.

Next up: A report on films I’m watching at the archive’s vaults on–no kidding–the Rue Gray.

The Metropole, Brussels, 1932.

Thanks to Jean-Paul Dorchain of the Archive for help in finding illustrations. And apologies to readers who came here and found only a stub earlier. An internet gremlin somehow purged the first version of this entry a few hours after it was posted.

B is for Bologna

A big crowd assembles for one of the nightly screenings on the Piazza Maggiore.

Not laziness or old age (we hope) but sheer busyness has reduced our Bologna blogging to a single entry this year. Last year we managed three entries, but this time there was just so much to see, from nine AM to midnight, that we couldn’t drag ourselves away to the laptop. That it was blazing hot and surprisingly humid may have given us less biobloggability as well. Still, DB has many pictures, so maybe a followup blog with unusual images of critics and historians disporting in the sun….

Some backstory: Hosted by the Cineteca of Bologna, Il Cinema Ritrovato is an annual festival of rediscovered and restored films. Every July hundreds of movies are screened in several venues. For our 2007 report, with more background and some orienting pictures, go here and then here and here. Watch a lyrical trailer for the event here.

As before, both KT and DB contribute to this year’s entry. But first, the breaking story.

Freder and Maria, together again for the first time

While we were there, the news of a long version of Metropolis broke. The estimable David Hudson offers a quick guide and an abundance of links at GreenCine. A rumor went around Bologna that fragments of the new Buenos Aires print would be screened, but instead there was a twenty-minute briefing anchored by Martin Koerber of the Deutsche Kinemathek. Along with him, Anke Wilkening (Friedrich-Wilhelm-Murnau Stiftung), Anna Bohn (Universitat der Kunste, Berlin), and Luciano Berriatua (Filmoteca Espanola) provided some key points of information.

*Provenance: The “director’s cut” was released in Argentina during the 1920s, with Spanish intertitles and inserts made at Ufa. A collector acquired a print. (Once more we have a collector to thank for saving film history.) When the Argentine film archive (Museo del Cine Pablo C. Ducros Hicken) received the copy in the 1960s, a 16mm dupe negative was made, and the nitrate original was discarded, a common practice at the time.

*Condition of the copy: The print is very worn, as the frame reproduced by Die Zeit indicates. Can the torrent of lines and scratches be eliminated? The rescue isn’t likely to be perfect; the damage is perhaps “beyond the reach of our algorithms,” as Martin puts it. To my eye, judging from the Die Zeit frames, many images are lacking in texture and contrast as well.

*Condition of the copy: The print is very worn, as the frame reproduced by Die Zeit indicates. Can the torrent of lines and scratches be eliminated? The rescue isn’t likely to be perfect; the damage is perhaps “beyond the reach of our algorithms,” as Martin puts it. To my eye, judging from the Die Zeit frames, many images are lacking in texture and contrast as well.

*Completeness: Contrary to some reports, virtually all the missing scenes are present on the Argentine print, the single exception being a small portion at a reel end. Among the new sequences are scenes filling in the roles of three characters (Georgy, Slim, and Josaphat), a car journey through the city, and moments of Freder’s delirium.

How can the researchers be confident that the print is so complete? It’s a fascinating story.

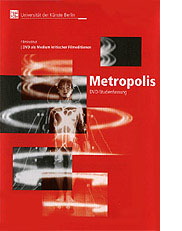

Metropolis has been reconstructed many times since the 1960s. In 2001, the Murnau foundation presented a digital restoration of the film supervised by Martin Koerber in collaboration with Enno Patalas. In this version, which is available on DVD (Transit Film, Kino International) about 30 minutes of the original material are missing. In 2003-2005 Enno Patalas and Anna Bohn together with a team at the University of the Arts in Berlin created a “Study Edition” version in which the missing footage was represented by bits of gray leader. For the first time the full length of the film was reconstructed with help from the the original music score.

In 2006 a “DVD study edition” was released by the Film Institute of the Berlin University of the Arts (Universität der Künste Berlin; DVD-Studienfassung Metropolis). This scrupulous version includes the original score, a lot of production material, and the complete script by Thea von Harbou. It’s a model of how digital formats can assist documentation of film history. The DVD incorporates production stills and intertitles from the missing scenes, and presents each scene in its original duration (sometimes with only gray leader onscreen). The editors determined the duration of each scene by a critical comparison of the remaining film materials with the music score and other source materials. This DVD edition was released in a limited edition available to educational and research facilities. For information see here or here.

In 2006 a “DVD study edition” was released by the Film Institute of the Berlin University of the Arts (Universität der Künste Berlin; DVD-Studienfassung Metropolis). This scrupulous version includes the original score, a lot of production material, and the complete script by Thea von Harbou. It’s a model of how digital formats can assist documentation of film history. The DVD incorporates production stills and intertitles from the missing scenes, and presents each scene in its original duration (sometimes with only gray leader onscreen). The editors determined the duration of each scene by a critical comparison of the remaining film materials with the music score and other source materials. This DVD edition was released in a limited edition available to educational and research facilities. For information see here or here.

Bohm and Patalas’s comparative method proved itself valid: The Buenos Aires footage fitted the gaps in their study edition perfectly!

A viewing copy will not be forthcoming immediately, given the restoration task, but sooner or later we will have a good approximation of the fullest version of one of the half-dozen most famous silent movies. Getting news like this while among archive professionals is one of the unique pleasures of Cinema Ritrovato. (Special thanks to Dr. Bohn for clarification on several points and to enterprising film historian Casper Tybjerg, who helped me get a copy of the Die Zeit issue.)

Two Davids and a Kevin: Robinson, Brownlow, and Shepard at a critics’ lunch.

Powell meets Bluebeard and Bartók

KT: One of the high points of the week for me was Michael Powell’s 1964 film of Béla Bartók’s short opera Bluebeard’s Castle. It was made for German television and shown in Bologna as Herzog Blaubarts Burg. Unfortunately it was programmed opposite the screening of fragments from Kuleshov’s Gay Canary, but Powell’s post-Peeping Tom films are so difficult to see that I made the difficult choice and gave up hope of seeing the entire Kuleshov retrospective.

Despite being relatively recent in comparison with most of the films shown during the week, Herzog Blaubarts Burg is one of the most obscure. I felt it was an extremely rare privilege to see it, one which I will probably never have again, at least in so splendid a print.

The film belongs to the late period of Powell’s career, after the controversial Peeping Tom had made it impossible for him to work within the mainstream film industry. It was produced by Norman Foster—though not the Norman Foster who directed Journey into Fear and several of the Charlie Chan and Mr. Moto films. This Norman Foster was an opera singer whose stage career was cut short by a dispute with Herbert von Karajan. His widow, Sybille Nabel-Foster, explained this and described how Foster produced and starred in two television adaptations, Herzog Blaubarts Burg and Die lustigen Weiber von Windsor (1966). Foster had originally approached Ingmar Bergman to direct the former, but when that proved impossible, Powell stepped in—and probably a good thing, too. It was definitely his kind of project.

The two performers are perfect for their roles. Foster plays Bluebeard brilliantly, having both a powerful bass voice and the necessary combination of handsomeness and a sense of threat. His co-star, the excellent soprano Ana Raquel Satre, recalls the pale beauties of some of Powell’s earlier films (Kathleen Byron as the increasingly mad Sister Ruth in Black Narcissus, Pamela Brown in I Know Where I’m Going!, and particularly Ludmilla Tcherina in The Tales of Hoffman), but she also bears a resemblance—perhaps deliberately enhanced through costuming and make-up—to Barbara Steele and other horror-film heroines of the 1960s.

The film was shot cheaply in a Salzburg studio, using garish, modernist settings against black backgrounds. These create a labyrinthine, floating space that avoids seeming stage-bound. (Hein Heckroth, the production designer, had previously worked on several Powell films, including The Red Shoes and The Tales of Hoffman.) I was reminded of Hans-Jürgen Syberberg’s Parsifal (1982), which looks somewhat less original in the light of Powell’s film.

As Nabel-Foster explained, after its initial screening on German television, Herzog Blaubarts Burg has been shown seldom because of rights complications with the Bartók estate. Non-commercial screenings have occurred on public television in the U.S. and Australia, but basically the film is off-limits until the copyright expires in 2015, seventy years after the composer’s death. Nabel-Foster has been providently preparing for a DVD release, gathering the original materials.

The print shown was a privately held Technicolor original from the era, in nearly mint condition. (The British Film Institute has a print as well.) The sparse subtitles written by Powell himself were added for this screening.

I’m not convinced that the film is quite the masterpiece that some claim, but it is a major item in Powell’s oeuvre nonetheless, and I felt privileged to have seen it in ideal conditions.

[July 12: Kent Jones, a great admirer of Powell and Bluebeard’s Castle, tells me that he programmed it at the Walter Reade in New York for a centenary retrospective of the director’s work in 2005. Foster’s widow introduced that screening as well.]

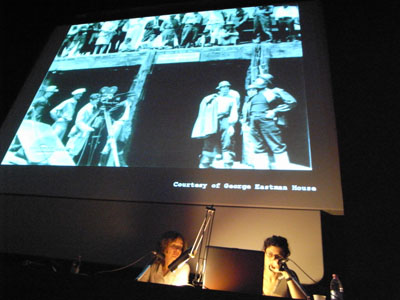

Janet Bergstrom and Cecilia Cenciarelli summarize their research on von Sternberg’s lost film The Sea Gull.

1908 and all that

KT: There were several programs of silent shorts, which I could only sample, as they tended to play opposite the Kuleshov films. As usual, the Bologna program included selections of short films from 100 years ago, so we were treated to numerous films from 1908. I was particularly pleased to see The Dog Outwits the Kidnappers, directed by Lewin Fitzhamon, who had made Rescued by Rover two years earlier. That film had been so fabulously successful that it had actually been shot three times as the negatives wore out from the striking of huge numbers of release prints.

The Dog Outwits the Kidnappers at first appears to be a sort of sequel (as it is described in the program), since it stars the same dog (Blair) who had played Rover, and again there is a kidnapped baby. It’s not really a sequel, though, since Cecil Hepworth, who had played the father in the earlier film, here appears as the kidnapper, and the dog is not named Rover. The new film is more fantastical than the original, since the dog races after the car in which the child is abducted and rather than fetching its master, effects the rescue itself by driving the car back home when the villain leaves his victim unattended!

Other 1908 films I particularly enjoyed: In Pathé’s Le crocodile cambrioleur, a thief hides inside a huge fake crocodile and crawls away, creating fear wherever he goes. The Acrobatic Fly by British director Percy Smith, provides a very close-up view of an apparently real fly juggling various small objects. (How was it done? It’s a mystery to me.)

Another retrospective series was “Irresistible forces: Comic Actresses and Suffragettes (1910-1915).” The suffragette films were rather depressing, despite the fact that many were meant at the time to be comic and amusing. Mostly the joke was how masculine these determined women were, a self-verifying proposition when the filmmakers often chose to have the suffragettes played by men. My favorite program was one involving early French female comics. I’ve long been fond of Gaumont’s Rosalie series since seeing a few at an early-cinema conference in Perpignon, France back in 1984. Rosalie, a chubby, cheerful little dynamo played by Sarah Duhamel, was highly entertaining in three films in the “France—Rosalie, Cunégonde et les autres…” program.

As Mariann Lewinsky, who devises these annual series, pointed out, Duhamel is the only early female French comic whose name we know. Léotine, represented here in Rosalie and Léotine vont au théâtre, is played by an anonymous actress. I had not encountered Cunégonde, also anonymous, before, but she proved to be quite amusing as well. I particularly liked Cunégonde femme du monde, where she plays a maid who dresses up as a society lady when her employers go off on a trip; the carefully constructed story and twist ending are impressive for such an apparently minor one-reeler.

It was a treat to see a succession of gorgeous prints of von Sternberg’s films. I particularly enjoyed seeing Thunderbolt (1929) again after many years. Back in 1983 I taught a survey film history course in which I used the director’s first talkie as my example of the transition to sound. Not a good example, I must admit, since Thunderbolt is completely atypical, with its highly imaginative use of offscreen sound. The second half, set primarily in a prison block, involves shouts from unseen cells and a small band that breaks into songs, often completely out of tone with the action, at unexpected moments. Eisenstein and the other Soviet directors would have thoroughly approved of its sound counterpoint. I have to admit that I prefer von Sternberg’s George Bancroft films (Underworld, Docks of New York, and Thunderbolt) to the Dietrich ones. Not only are the plots simpler and more elegant, but they contain a genuine element of emotion that is not, as in the Dietrich series, frequently undercut by irony.

I didn’t make it to many of the CinemaScope films playing on the very big screen in the Cinema Arlecchino theater, but I did enjoy two westerns. Anthony Mann’s Man of the West (1958) and John Sturges’ Bad Day at Black Rock (1954) both looked terrific and were highly popular with everyone we talked to. The latter was particularly a revelation, since in contrast to the Mann, it hasn’t had much of a reputation among cinephiles.

A Rodchenko angle for Yuri Tsivian.

Teacher and experimenter

DB: As Kristin mentioned, we missed a lot of the “Hundred Years Ago” series—a pity, since 1908 is a miraculous year—in order to keep up with one of our favorite directors, Lev Kuleshov.

In the 1960s and 1970s, it was common to say that Eisenstein and Vertov were the most experimental Soviet directors, while the others were more conventional. Then we realized that in films like Arsenal (1928), Dovzhenko had his own wild ways. Then we discovered the Feks team, Kozintsev and Trauberg, and the bold montage of The New Babylon (1929). A closer look at Pudovkin, particularly his early sound films like A Simple Case (1932) and Deserter (1933), revealed that he too was no timid soul when it came to daring cutting and image/ sound juxtapositions. But surely their mentor Kuleshov, admirer of Hollywood continuity and proponent of the simplest sorts of constructive editing, played things safe?

Wrong again. Just as we must reevaluate the other master Soviet directors (even in their purportedly safe Stalinist projects), so too does Kuleshov deserve a fresh look. He got this thanks to Yuri Tsivian, who with the help of Ekatarina Hohlova (right; granddaughter of Kuleshov and his main actress Aleksandra Hohlova) and Nikolai Izvolov, mounted a superb retrospective. It ranged from Kuleshov’s first solo effort, Engineer Prite’s Project (1918) to his final film, the short feature Young Partisans (1942-3, never released).

Wrong again. Just as we must reevaluate the other master Soviet directors (even in their purportedly safe Stalinist projects), so too does Kuleshov deserve a fresh look. He got this thanks to Yuri Tsivian, who with the help of Ekatarina Hohlova (right; granddaughter of Kuleshov and his main actress Aleksandra Hohlova) and Nikolai Izvolov, mounted a superb retrospective. It ranged from Kuleshov’s first solo effort, Engineer Prite’s Project (1918) to his final film, the short feature Young Partisans (1942-3, never released).

My admiration for Kuleshov, confessed in an earlier blog entry, already led me to spot some weirdnesses in Mr. K’s official classics. The Extraordinary Adventures of Mr. West in the Land of the Bolsheviks (1924) boasts some very un-formulaic cutting in certain passages (including an upside-down shot when cowboy Jeddy ropes the sleigh driver), and By the Law (1926) makes chilling use of discontinuities when the scarecrow Hohlova holds the Irishman at gunpoint. But thanks to the retrospective we can confidently say that Kuleshov was no less venturesome, at least in certain projects, than his pupils.

Soviet specialists already suspected that The Great Consoler (1933) was K’s sound masterpiece, and another viewing confirmed it. It incorporates three registers. William S. Porter, in prison but serving in the pharmacy, witnesses brutality and oppression and is driven to drink. Under the name O. Henry he writes cheerfully sentimental tales as much to console himself as to charm readers. His stories are in turn consumed by shopgirls like Dulcie, a romantic who may not realize how unhappy she is. Kuleshov adds a level of sheer fantasy, represented by a pastiche silent film dramatizing O. Henry’s “A Retrieved Reformation,” in which a safecracker trying to go straight reveals his identity by saving a girl trapped in a bank vault. The embedded story features characters from the other two levels, convict Jimmy Valentine and Dulcie’s lover, a vaguely sadistic businessman in a ten-gallon hat.

The Great Consoler reminds us of the popularity of O. Henry in the Soviet Union, both among readers and the Russian Formalist literary theorists, who were fascinated by his flagrant, playful artifice. (Boris Eikhenbaum’s essay on the writer is one of the most brilliant pieces of literary analysis I know.) Even though Kuleshov must denounce Porter for reconciling the masses to their misery under capitalism, the zest of the embedded film and the unique architecture of the overall project pay tribute to another entertainer who did not forgo experimentation. And Kuleshov’s image of a writer in prison probably had Aesopian significance for artists in the era of Socialist Realism.

K’s other major sound experiment, less widely seen, is Gorizont (1932). The title is at once a man’s name and the Russian word for “horizon”—a metaphor literalized in the final shot of a train leaving a tunnel. As Yuri pointed out, it is one of the few Soviet films centered on a Jew, and so the formulaic growth-to-consciousness plotline takes on a new resonance in the light of Slavic anti-semitism. Lev Gorizont is an amiable, somewhat thick young man who dreams of emigrating to the US to make his fortune. But in New York he finds only poverty and disillusionment, eventually returning home to help make a better society. Famous for its use of sound, Gorizont contains a passage of imaginative “counterpoint.” Both Lev and his friend Smith have been jilted by the social-climber Rosie. As they talk, we hear warm piano music, but not until the end of the scene does Smith speculate that probably Rosie is somewhere listening to Chopin. The music has retrospectively functioned somewhat like crosscutting, suggesting that Rosie now lives among the wealthy.

Kuleshov, like Eisenstein, gained his fame for his ideas on editing and sound montage, but both men were deeply interested in performance. Kuleshov’s idea that the film actor should become an angular mannequin carries on the impulse of Meyerhold’s biomechanics, and he anticipated CGI software in suggesting that human action could be plotted on a three-dimensional grid. Still, Kuleshov usually gives his figures a fluid dynamism that doesn’t seem mechanical. The three narrative registers of The Great Consoler are delineated largely through acting: naturalistic and slowly paced in the prison scenes, rigid and posed in the shopgirl romance, and broad and eccentric in the embedded silent movie.

Kuleshov’s performance theories popped out of other films in the series. What survives of The Gay Canary (1929) centers on a cabaret actress courted by lustful reactionaries during the civil war, and her scenes of fury, as she flings around flowers, vases, and pieces of furniture, come off as acrobatic rather than realistic. Naturally, the circus milieu of 2 Buldy 2 (1929) encourages stunts. A father and son, both clowns, are to perform together for the first time, but the civil war separates them, and the elder Buldy, tempted for a moment to acquiesce to the White forces, casts his lot with the revolution. At the climax Buldy Jr. escapes the Whites thanks to flashy trampoline and trapeze acrobatics; the gaping enemy soldiers forget to shoot. Even Kuleshov’s more naturalistic films show flashes of kinetic, stylized acting. A partisan listens to a boy while draping himself over a door. A Bolshevik official answers the phone by reaching across his chest, twisting his body so the unused arm can hike itself up, right-angled, to the chair.

The interaction of the body with props occurs with a special flair in Young Partisans. A Bolshevik partisan tells some children how a boy saved his life in a German-occupied town (This flashback was directed by Igor Savchenko and functions as a short film on its own.) Having learned their lesson, the kids gather in their schoolroom and under the teacher’s eye draw a map of the partisans’ camp. But when Nazi soldiers burst in, the teacher flips the blackboard over; now all we see is algebra.

A scene of Hitchcockian suspense ensues: Will the Germans turn over the blackboard and discover the map? The tension is enlivened by a grotesque moment, when one alcoholic soldier finds a jar holding a pickled frog and decides to drink the formaldehyde. “Draw a map—show me where the partisans are!” the officer demands. He flips the blackboard, and in a split-second we see a boy crouching behind it; the blackboard swings into place toward us, the map now erased. The boy ducks into his seat, brushing off chalk dust.

There were plenty of other revelations. We got the reconstructed Prite (was it the first really modern Soviet film?), a bit of an original Kuleshov experiment in constructive editing, and a tantalizing fragment from The Female Journalist (1927), with a surprisingly pensive Hohlova as a modern-day reporter. Sasha (1930), directed by Hohlova herself, was a sympathetic portrait of a pregnant woman. An educational film called Forty Hearts (1930) explained the need to electrify the Soviet countryside and was brightened by faux-naïve animation. Timur and His Crew (1942), with some of the charm of a Nancy Drew movie, showed Young Pioneers helping on the home front; it unexpectedly centered on a girl’s devotion to her military father.

There were plenty of other revelations. We got the reconstructed Prite (was it the first really modern Soviet film?), a bit of an original Kuleshov experiment in constructive editing, and a tantalizing fragment from The Female Journalist (1927), with a surprisingly pensive Hohlova as a modern-day reporter. Sasha (1930), directed by Hohlova herself, was a sympathetic portrait of a pregnant woman. An educational film called Forty Hearts (1930) explained the need to electrify the Soviet countryside and was brightened by faux-naïve animation. Timur and His Crew (1942), with some of the charm of a Nancy Drew movie, showed Young Pioneers helping on the home front; it unexpectedly centered on a girl’s devotion to her military father.

One of the biggest surprises was news of Dokhunda (1936), an ethnographically based fiction set in Tazhikistan. Although the film is lost, Nikolai has reconstructed its plan, revealing that Kuleshov adopted a strange preproduction method. He prepared “living storyboards,” photos of the cast enacting the scenes. He then drew and scratched on them, creating busy, nervous backgrounds or changing the figures’ features and hair styles—Kuleshov as pre-Warhol scribbler, or a graffiti artist tagging his own images.

Nikolai has also finished a DVD edition of Prite that exemplifies what he calls hyperkino, a way of annotating and comparing a film’s images, texts, and supplementary materials for instant access. Another project involves the Yevgenii Bauer classic, The King of Paris (1917), which Kuleshov completed. We haven’t had the intertitles for this, however, but now Nikolai has discovered them, and they will go on the DVD version that is being completed. For more information on these projects and Dokhunda, go to hyperkino.net.

So Kuleshov stands revealed as more supple and ambitious than most of us once thought. Once more Bologna plays to its strengths—filling in gaps but also forcing us to rethink what we thought we knew.

The key issue: What the hell am I going to be seeing now? From left, Olaf Muller, Jonathan Rosenbaum, Don Crafton, Haden Guest, and KT.

So much else to report, so little time. Besides The King of Paris, there was a string of fine 1910s films. Raoul Walsh’s Pillars of Society (1916), while not a patch on his Regeneration of the previous year, offered a solid adaptation of Ibsen. The Dawn of a Tomorrow (1915), James Kirkwood’s Mary Pickford vehicle, seemed to me flat and talky, but others liked it. For me the outstanding item was Paul Garbagni’s In the Spring of Life (1912). Beautifully directed in the tableau style, with precise depth choreography and a stirring scene of a theatre consumed by fire, it starred three men who would become great directors very soon: Sjöström, Stiller, and Georg af Klercker.

Not to mention the von Sternbergs (I liked An American Tragedy much more on this outing), the Scope revivals (Man of the West, Ride Lonesome in a handsome digital restoration from Grover Crisp), my first viewing of Duvivier’s La Bandera (1935), the Monta Bell items (most notably the incessantly energetic Upstage from 1926), and on and on.

What can Gianluca Farinelli, Peter von Bagh, and Guy Borlée, along with their devoted staff members, do for an encore? Bravo! Now take a rest.

Standing Room Only for the rarely seen Children of Divorce (Sternberg/ Lloyd, 1927).

Times go by turns

Kristin here—

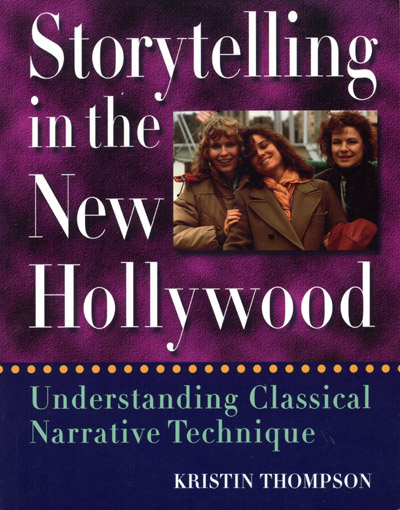

Last week during the Society for Cognitive Studies of the Moving Image conference here in Madison, I got to talking with Prof. Birger Langkjær of the University of Copenhagen. He asked me some questions about the concept of “turning points” in film narrative as I had used it in my book, Storytelling in the New Hollywood: Understanding Classical Narrative Technique. Specifically he wondered if turning points invariably involve changes of which the protagonist or protagonists are aware. The protagonist’s goals are usually what shape the plot, so can one have a turning point without him or her knowing about it?

I couldn’t really give a definitive answer on the spot, partly because it’s a complex subject and partly because I finished the book a decade ago (for publication in 1999). It seemed worth going back and trying to categorize the turning points in films I analyzed. Describing those turning points more specifically could be useful in itself, and it might help determine to what extent a protagonist’s knowledge of what causes those turning points typically forms a crucial component of them.

Characteristics of turning points

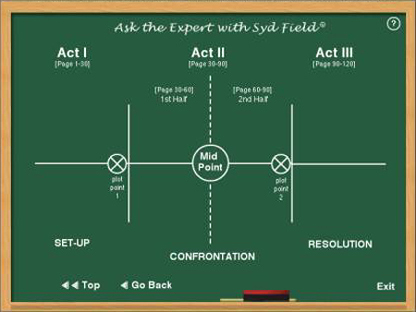

Most screenplay manuals treat turning points as the major events or changes that mark the end of an “act” of a movie. Syd Field, perhaps the most influential of all how-to manual authors, declared that all films, not just classical ones, have three acts. In a two-hour film, the first act will be about 30 minutes long, the second 60 minutes, and the third 30 minutes. The illustration at the top shows a graphic depiction of his model, which includes a midpoint, though Field doesn’t consider that midpoint to be a turning point.

I argued against this model in Storytelling, suggesting that upon analysis, most Hollywood films in fact have four large-scale parts of roughly equal length. The “three-act structure” has become so ingrained in thinking about film narratives that my claim is somewhat controversial. What has been overlooked is that I’m not claiming that all films have four acts. Rather, my claim is that in classical films large-scale parts tend to fall within the same average length range, roughly 25 to 35 minutes. If a film is two and a half hours rather than two hours, it will tend to have five parts, if three hours long, then six, and so on. And it’s not that I think films must have this structure. From observation, I think they usually do. Apparently filmmakers figured out early on, back in the mid-1910s when features were becoming standard, that the action should optimally run for at most about half an hour without some really major change occurring.

Field originally called these changes “plot points,” and he defined them as “an incident, or event, that hooks into the story and spins it around into another direction.” Perhaps because of that shift in direction, these moments have come more commonly to be called “turning points.” But what are they? Field’s definition is pretty vague.

In Storytelling I wrote, “I am assuming that the turning points almost invariably relate to the characters’ goals. A turning point may occur when a protagonist’s goal jells and he or she articulates it .… Or a turning point may come when one goal is achieved and another replaces it.” I also assumed that a major new premise often leads to a goal change (p. 29). “Almost invariably” because I don’t assume that there are hard and fast rules. As with large-scale parts, my claims about other classical narrative guidelines aren’t prescriptive in the way that screenplay manuals usually are.

To reiterate a few other things I said about turning points. They are not always the same as the moments of highest drama. Using Jaws as my example, I suggest that the moments of decision (not to hire Quint to kill the shark and later to hire him after all), rather than the big action scenes of the shark attacks, shape the causal chain (p. 33).

Not all turning points come exactly at the end of a large-scale part of the film (an “act” in most screenplay manuals). A turning point might come shortly before the end of a part, or the turning point may come at the beginning of the new part (pp. 29-30). The final turning point that leads into the climax comes when “all the premises regarding the goals and the lines of action have been introduced” (p. 29).

Most screenplay manuals consider goals to be static. To me, “Shifting or evolving goals are in fact the norm, at least in well-executed classical films” (p. 52). This doesn’t mean that the goal changes at every turning point. Instead, the end of a large-scale part may lead to a continuation of the goal(s) but with a distinct change of tactics (p. 28).

One big advantage of talking about different types of turning points is that it allows the analyst to see how the different large-scale parts function. A well-done classical film doesn’t just have exposition and a climax with a bunch of stuff in the middle. (Field calls that long second act the “Confrontation” in the diagram above.) I believe that once the setup is over, there is a stretch of “complicating action,” which often acts as a sort of second setup, creating a whole new situation that follows from the first turning point. The third part is the “development,” which often consists of a series of delays and obstacles that essentially function to keep the complications from continuing to pile up until the whole plot becomes too convoluted. The development also serves to keep the climax from starting too soon. The third turning point is the last major premise or piece of information that needs to be set in place before the action can start moving toward its resolution in the climax.

David uses this approach to large-scale parts in his online essay, “Anatomy of the Action Picture,” which discusses Mission: Impossible III.

TYPES OF TURNING POINTS

Returning to some of the examples I used in Storytelling, let’s see what sorts of changes their turning points involve. In most of these cases, the protagonist is aware of what is happening, but there are some exceptions or nuances.

1. An accomplishment, later to be reversed

Top Hat: end of setup, Jerry and Dale fall in love, but she soon conceives the mistaken idea that he is married to her best friend. (p. 28)

Tootsie: end of setup, Michael gets a job, but the results will throw his life increasingly into chaos. (p. 60)

Parenthood: end of complicating action, the parents seem to be making progress in solving their problems. (p. 268)

2. Apparent failure, reiteration of goal

The Miracle Worker: end of development, parents remove Helen from cabin, Anne states goal again. (p. 28)

The Silence of the Lambs: turning point comes at beginning of development, Chilton makes Lecter a counter-offer, removing him from the FBI’s charge. The FBI’s tactic has failed, but soon Clarice visits Lecter to pursue her questioning. (p. 123)

Here’s a case where we don’t see Clarice learning about Chilton’s treacherous undermining of the FBI’s efforts. A few scenes later she simply shows up to visit Lecter, and we realize that she has not given up her goal of getting information from him. Clearly a turning point can occur without the main character’s knowledge, but he or she will usually learn about it shortly thereafter.

Groundhog Day: end of development. Failure to save old man. No reiteration of goal, which is implicitly that Phil will continue to improve himself. (p. 147)

2a. Failure, new goal

Amadeus: end of complicating action, Salieri declares that he is now God’s enemy and will ruin Mozart. (p. 195)

Amadeus is an example of what I call a “parallel protagonist” film. Here Salieri is aware of his own decision, but Mozart never learns that his colleague hates him so. Parallel protagonists have separate goals, but they need not be aware of each other’s goals. The same would be true in a film with multiple protagonists, to the extent that they have separate goals.

2b. Failure, lack of goal

Groundhog Day: end of complicating action, suicidal despair. (p. 144)

Amadeus: end of setup, Salieri humiliated by Mozart, conceives strong resentment but no specific goal. (p. 191)

Parenthood: end of development, the parents are all resigned to their failures. (pp. 275-76)

3. Major new premise, reiteration of strategy

Witness: end of complicating action, Carter tells Book to stay hidden. (p. 29)

The Wrong Man: end of complicating action, Manny is freed on bail; he has the chance to try and prove his innocence. (p. 39)

Terminator 2: end of development, Sarah, Terminator, and John steal chip from Cyberdine, continue in their attempt to destroy it. (p. 42)

Amadeus: end of second development, Constanza leaves Mozart, allowing Salieri the access that will permit him to fulfill his goal of killing his rival. (p. 205)

4. Protagonist/Important character makes a decision, then changes or modifies goal

Little Shop of Horrors (1986): end of complicating action, Seymour agrees to kill someone to feed blood to Audrey II. (p. 29)

The Godfather: end of development, Michael says family will go legit, asks Kay to marry him. (p. 30)

Casablanca: end of complicating action, Rick rejects Ilsa’s account of her relationship with Victor. (p. 32)

The Producers: end of setup, Leo decides to join Max in committing fraud. (p. 38)

Tootsie: end of complicating action, Michael decides to start improvising Dorothy’s lines, setting up “her” success. (p. 64)

Back to the Future: end of development. Martie decides to leave a message for Doc warning him about the Libyan attack; the result is to save Doc from being killed. (p. 94)

Desperately Seeking Susan: end of setup, Roberta apparently decides to pursue Susan, change her boring life. (p. 166)

Such decisions obviously form the basis for turning points fairly frequently, and by definition the protagonist is aware of what is happening.

5. Major Revelation, new goal or move into climax

Witness: end of setup, Book is told the killer is a cop, changes tactics, flees. (p. 28)

Witness: end of development, Book learns partner has been killed, realizes he must act. (p. 29)

The Bodyguard: end of development, revelation of Nikki as villain, attack on house, death of Nikki. (p. 31)

Terminator 2: end of setup, John discovers the Terminator must obey him, sets goals of protection without killing and of rescuing Sarah from the asylum. (p. 41)

Terminator 2: end of complicating action, Sarah realizes that the war can be prevented, conceives goal of killing Dyson. (p. 42)

Tootsie: end of development, Michael’s agent tells him he must get out of playing Dorothy without being charged with fraud. (p. 69)

The Silence of the Lambs: end of setup, Clarice finds the body in the warehouse and realizes that Lecter is willing to help her. (p. 115)

The Silence of the Lambs: end of development, Clarice and Ardelia realize “He knew her,” the clue that will lead to the solution. (p. 126)

Alien: end of development, revelation that the “company” and Ash are prepared to sacrifice the crew; will lead to decision by survivors to abandon the ship and save themselves. (p. 299)

Such revelations usually involve the protagonist knowing what is happening, but I believe there are exceptional cases where the viewer learns something that the protagonist does not. This kind of revelation often involves either villains turning out to be allies or apparent allies turning out to be villains.

Take the case of Demolition Man. At 54 minutes into the film, about nine minutes before the end of the complicating action, the audience learns that the apparently benevolent Dr. Cocteau (Nigel Hawthorne), who has developed the new pacifist society of Los Angeles, is a ruthless villain. This moment isn’t the turning point that ends the complicating action; I take that to be the escape of the “Scraps,” the rebels who oppose Cocteau, from their underground prison. Most of those nine minutes consist of the hero, John (Sylvester Stallone) meeting Cocteau and going out to dinner with him. John shows signs of strongly disliking the new society, and he refuses to kill the rebels when they escape. Still, there is no sign that he considers Cocteau a villain. Rather, John thinks of himself as a misfit and expresses a desire to leave the new Los Angeles. The turning point that ends the complication depends on his assumption that Cocteau on his side, even if John considers the leader’s bland society to be unattractive.

The development portion is full of typical delays: the scene of John visiting Lenina Huxley’s (Sandra Bullock) apartment, where she invites him to have virtual sex, and the following scene of John exploring the odd, modernistic apartment assigned to him. At 74 minutes in, or about six minutes before the end of the development, John begins to learn of Cocteau’s true nature. He confronts Cocteau in the latter’s office and nearly shoots him. The scene where John tells the members of the police department who remain loyal to him that they will invade the underground prison to capture Cocteau’s violent agent, Simon Phoenix (Wesley Snipes) marks the end of the development, with a new, specific goal determining the action of the climax.

Here is a case where for a significant portion of the narrative the protagonist remains ignorant of something that the audience has been shown. Even here, however, John displays a dislike of Cocteau and what he has done to Los Angeles society. Classical films seem disinclined to show their heroes as thoroughly deluded. John’s underlying decency and common sense make him ready to distrust a leader whom everyone else, including Lenina, admire.

6. Enough information accumulates to cause the formulation of goals

Back to the Future: end of complicating action, goals of synchronizing with lightning storm, getting Marty’s father and mother together at dance. (p. 90)

Desperately Seeking Susan: end of complicating action. Information about gangsters and growing attraction to Dez lead to convergence of Roberta’s goals. (p. 170)

Parenthood: end of setup, in this case with multiple goals formed for four separate plotlines.

7. A disaster, accidental or deliberate, changes the characters’ situations/goals

The Wrong Man: end of setup, Manny is mistakenly arrested. (p. 39)

Jurassic Park: end of complicating action, Nedry shuts down the electricity grid of the park, letting the dinosaurs loose. (p. 32)

Jaws: end of complicating action; the attack involving his son makes Brody force the mayor to accept his original, thwarted tactic of hiring Quint. (p. 34)

Alien: end of setup, facehugger attaches itself to Kane. The goal conceived shortly thereafter is to investigate it and save him. (p. 292)

Alien: end of complicating action, alien bursts from Kane’s stomach; goal becomes to save the crew and ship. (p. 295)

Desperately Seeking Susan: end of development, Roberta’s arrest leads to a low point, and she opts to turn to Dez for help. (p. 172)

Amadeus: end of first development, death of Leopold, which Salieri later exploits in his plot against Mozart. (p. 201)

The Hunt for Red October: end of complicating action, Ramius realizes he has a saboteur aboard and needs Ryan’s help; Ryan starts planning actively to help him. (p. 233)

8. Protagonist’s tactics are blocked or he/she is forced to use the wrong tactics

Jaws: end of setup, Brody’s desire to hire Quint rejected. (p. 23)

Back to the Future: end of setup, Doc sets time machine’s date; after new large-scale section begins, attack by Libyans accidentally sends Marty back to 1955. (p. 85)

Groundhog Day: end of setup, Phil trapped in repeating time, goal of becoming a network weather forecaster destroyed. He soon opts for irresponsible self-indulgence. (p. 139)

9. Characters working at cross-purposes resolve their differences

Jaws: end of development, the three main characters bond, allowing them to cooperate to kill the shark. (p. 35)

The Hunt for Red October: end of development, Ramius and Ryan make contact, with Captain Mancuso’s help, they start working together. (p. 237)

10. A supernatural premise determines a character’s behavior

Liar, Liar: end of setup, Max wishes that his father would have a day where he is unable to tell a lie. Also end of complicating action, where Max fails to cancel the wish. (p. 38)

11. The protagonist/major character succeeds in one goal, allowing him/her to pursue another

Liar, Liar: end of development, Fletcher wins his court case, freeing him to try and regain his wife and son. (p. 39)

The Hunt for Red October: end of setup, Ramius learns that the silent feature of his new submarine works; he apparently intends some sort of attack on the US but is in fact plotting an elaborate ruse to defect. (p. 225)

These examples suggest that protagonists usually do know about the major events that form turning points, or they learn about them shortly after they occur. The main exception would seem to be when there are two major parallel characters, one of whom is to some extent villainous, as in the case of Amadeus, where one of the characters is duped. This reminds me of The Producers, where Max and Leo leave the theater early, convinced that they have succeeded in their goal of creating a box-office disaster. Lingering in the theater, the narration allows us to see the transition from audience disgust to fascination. Only after the audience comes into the bar where the two partners are celebrating do they realize what has happened (“I never in a million years thought I’d ever love a show called Springtime for Hitler!”) To understand the irony and/or humor in such situations, the film spectator must at least briefly know more than the main characters do.

The examples also confirm that character goals seldom endure unchanged across the length of a film. Revelations, decisions, disasters, supernatural events, and presumably others kinds of causes frequently cause major shifts in characters’ goals or at least in the tactics they employ in pursuing them. Even in what seems like a fairly straightforward thriller like Alien, the crew’s assumptions that they must loyally protect their spaceship are completely reversed at the end of the development, and the narrative turns into an attack on corporate greed and ruthlessness. Whatever one thinks of classical Hollywood films, they are usually more complex than the three-act model allows for.

Note: My title comes from Robert Southwell’s poem of the same name.

[July 11: Jim Emerson has made some insightful comments on this entry on his Scanners blog.]

Reflections in a crystal eye

Whew! After many months of work, we finally sent in our revised third edition of Film History: An Introduction. Elsewhere on this site you can read about its earlier incarnations, and we expect to say more about it as it approaches publication in February 2009. But writing this tome isn’t as fast as webposting, for sure.

So how did we celebrate? A meal out and Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull (after about sixteen trailers for Paramount and DreamWorks releases). As with Beowulf and Ratatouille, we talk/ write about it together, but not in dialogue form. Kristin gets her time at the podium, then David. And there are of course spoilers.

Don’t even mention pyramid power

Kristin here:

I enjoyed the first half or so of IJatKotCS, but gradually it occurred to me that it wasn’t really building. It was violating the basic law of suspense films, which is to make your villain threatening and the things at stake important. Sure, in the B-film serials that inspired the Indiana Jones films, the premises are ludicrous. But so are the sets and the acting and just about everything about them, because they were so cheaply and quickly made.

With Indiana Jones, these adventure films become high-budget productions with the biggest, best special effects that money can buy. They star actors who have won or been nominated for Oscars. Moreover, the scripts don’t imitate the clichéd, bare-bones plots of the Bs. These are complicated stories that not only move ahead at a pace undreamed of in the serial days, but they toss in many little details and in-jokes in the backgrounds. With Steven Spielberg directing, one expects the non-stop thrills to also make sense, at least in a casual way.

Eventually I became distracted by the fact that certain things stopped making sense to me. Most obviously, what is at stake with that crystal skull? The Soviets want it, and Irina Spalko informs Indy that it’s to make a psychic weapon. Hmmm. And what is that, exactly? She doesn’t explain, and it’s clear that the Reds don’t know enough about the crystal skull to really understand what they’d do with it. In fact, they need Indy to help them every step of the way, and after a certain point his expertise becomes irrelevant, and they’re all dependent on Prof. Oxley to lead them to the kingdom.

I suspect most people’s reaction to her “psychic weapon” announcement is to think she’s nuts, deluded. The skull has apparently driven Oxley crazy (John Hurt playing loony as only he can do). Or did that just happen because he was locked in a very grim Peruvian insane asylum? We’re allowed to go on wondering if the skull has any psychic powers until the scene where Indy gets strapped in a chair and forced to stare into the eyes of the skull. The fact that he is so profoundly shaken by the experience finally shows that the object does have some sort of psychic effect.

But how could it be a weapon? Earlier an atomic bomb has gone off, and that’s engineered by our side, the good guys. How could a psychic weapon top that? Are the Russkies going to strap all the American soldiers one by one into chairs and make them stare into the skull? Talk about creeping Communism!

Spalko can’t explain it to us, since she is trying not only to get the skull but to figure out its secrets. Up to the very end, she says “I vunt to know.”

Of course, ignorance on the part of the villains need not be a problem. In Raiders of the Lost Ark, the Nazis didn’t know what power the Ark of the Covenant contained until it was too late. At least there, though, we understand from early on that the Ark really is dangerous in what is presumed to be a physical way. Moreover, there the villains were Nazis. We know what horrors the Nazis perpetrated on the world, and we and our allies actually went to war with them. With the Soviets, it was largely a long, tense brinksmanship. Luckily we never found out what a war with the USSR would be like. Today, well after the Soviet Union imploded on its own, the paranoia over reds in our midst seems quaint in an adventure film. Early on Indy and his department chair (Jim Broadbent) lose their jobs, and in a glum scene they deplore how Americans’ irrational fear of Communism has caused it. Yet soon after we discover that there really are Communist spies looking to steal America’s secrets. A mixture of tone, to say the least.

In Raiders, the Nazis seemed to be part of a worldwide network of spies. Spalko seems to be operating with only the group of soldiers that accompanies her. She never reports back to “headquarters.” One wonders if maybe Khrushchev sent her off on a wild-goose chase to get rid of her for a while.

Professor Jones Flunks Archaeology 101

One thing that distracted me and that seems to vitiate the notion of real threat in IJatKotCS is the fact that it’s based on hoaxes and wacko theories. At least there’s some archaeological evidence that elements of the Bible have their bases in real events. There may have been some sort of Ark of the Covenant and a Holy Grail. But to base the premise of the film on Chariots of the Gods (Erich von Däniken, 1968) and crystal skulls gives it a certain ludicrous quality that wasn’t there in the earlier films’ premises, wild though they were.

The film flits lightly past the nuts and bolts of how that Kingdom of the Crystal Skull came to be. Presumably, as in Chariots of the Gods, the aliens arrived and traveled around giving instructions on how to build such things as pyramids and Easter Island statues. The room in IJatKotCS where artifacts from Egypt, China, and other ancient cultures are gathered implies that long ago the aliens visited the earth, collected examples of the fruits of their teachings, and … instead of putting them in their space ship to take home, they left them in a chamber that would be crushed when the Kingdom built over the space ship is destroyed. (Don’t get me started on where the ancient Peruvian warriors who pop out of the walls to briefly chase the good guys came from.)

Then there are the skulls. The “real” crystal skulls held in museums, most notably the British Museum one referred to in the film, have been shown to be objects made in modern times, probably within the past 150 years. Those skulls, however, are of normal proportions. The ones in the movie are strangely elongated. Head-binding, Indy offhandedly explains.

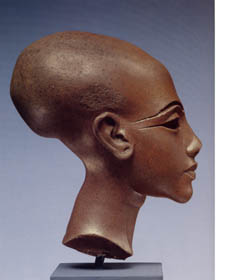

There’s another apparent source for this, one that I’m familiar with. The pharaoh Akhenaten, famed equally for inventing monotheism back in the 14th Century BCE and for being married to Nefertiti, has been the subject of much far-out speculation. The art of his era, the Amarna Period, shows his family with strikingly elongated skulls, as in the quartzite head of the statue of a princess at the left. Head-binding, various medical syndromes, and pictorial stylization have been posited. One imaginative claim has it that Akhenaten and his family actually were space aliens.

There’s another apparent source for this, one that I’m familiar with. The pharaoh Akhenaten, famed equally for inventing monotheism back in the 14th Century BCE and for being married to Nefertiti, has been the subject of much far-out speculation. The art of his era, the Amarna Period, shows his family with strikingly elongated skulls, as in the quartzite head of the statue of a princess at the left. Head-binding, various medical syndromes, and pictorial stylization have been posited. One imaginative claim has it that Akhenaten and his family actually were space aliens.

In fact, we still have no convincing explanation as to why this style occurred in Amarna statuary. (The Egyptian expedition I work on is at Amarna, the ancient city built by Akhenaten, and I work with statuary fragments found there.) The film, of course, doesn’t bring Akhenaten into it, though I think I did spot a photo of the seated statue of him in the Louvre on the chalkboard of Indy’s classroom. Akhenaten is a figure of considerable interest to New Age enthusiasts. Every now and then a group of people in white robes and turbans actually come to Amarna to worship in the ruins of the temples.

The ancient-aliens-visited-earth premises and the less explicit references to Amarna are woven in with El Dorado and with the Roswell myth that modern aliens visited earth. There’s even a nod to the Alien Autopsy film that David discussed in an entry on “Film Forgery.” The film also brings in the mysterious Nazca Lines, the shapes carved into the earth over which Indy and Mutt fly as they arrive in Peru. Some have claimed that the lines are runways for alien ships, and I think the film tries to imply that. But why would a flying saucer that takes off (and presumably lands) vertically need a runway, let alone one shaped like a monkey or any of the other complex figures that survive today?

The silliness that hovered near the edge of plausibility in the earlier films has crossed that line. At least the first and third movies made an effort to ground their mcguffins in real history and real places. Tanis, where a lengthy portion of Raiders takes place, is a real set of ruins in Egypt. In Last Crusade, Indy and his father can spar by showing off their knowledge of actual or apparently actual history. (I’ll leave it to the comments on the “goofs” page of the Internet Movie Data-base to deal with the transfer of the Mayans from Central America to Peru.) Each of those films was a race to prevent a lethal object falling into the hands of those who would both desecrate it and use it for evil purposes. Crystal Skull is a race to figure out what the apparently dangerous object is, given that the only person who knows, Oxley, is conveniently rendered unable to explain it.

Indy and his group win the race and get to the chamber ringed by crystal skeletons first, so that Spalko is effectively defeated before she gets there, though she doesn’t know that yet. Which brings me to the last thing that baffled me. Why, if the thirteen skeletons were separate beings, as they are depicted in the wall paintings, do they merge into one before being restored to life? Apparently the space ship was waiting to depart because, unlike in E.T., the aliens didn’t want to leave one of their number behind. But is there more than one alien left at the end to depart in the huge ship? Does the ship wait simply because it brought only one passenger, and that passenger can’t start it moving until it gets its head back? Yet surely there would have had to have been a crew to help build all those ancient wonders and bring the evidence back to the “kingdom.”

Maybe a second viewing would clear all this up, but the old serials didn’t need second viewings to be understood—and neither did the earlier Indy films.

The Spielberg Touch

DB here:

Kristin’s critique reminds us that the classic Hollywood structure demands a linear logic, but not a plausible or even particularly deterministic one. Like other action films, Crystal Skull follows the template she pointed out in her New Hollywood book: four parts, the first three running about half an hour and the climax somewhat shorter, the whole capped by an epilogue. It goes to show the difference between plot structure and the events of the fictional world that structure presents. The structure can make preposterous or puzzling chains of action seem acceptable—especially if it whisks them along.

I was taken, as usual, by Spielberg’s brisk direction. In the last decade he’s had a remarkably hot hand. Amistad, Saving Private Ryan, A. I., Minority Report, Catch Me If You Can, The Terminal (much underrated, I think), The War of the Worlds, and Munich are very strong movies. For all their faults (sometimes those slippery endings), they would be enough to establish a younger director at the very top. So I was watching for what I take to be The Spielberg Touch.

His staging is still solid and resourceful. When he has to let people talk, he moves them around the set, avoiding those dreary passages of stand-and-deliver that most directors today resort to. (Check the dialogue scenes from The Matrix Reloaded.) In a soda fountain, he lets your attention drift from the exposition between Mutt and Indiana to the teenyboppers behind them, to the point where I was distracted from Mutt’s explanation of those muddled plot premises Kristin points out.

Spielberg has said that he favors lengthier shots than are typical today. That’s true in most of his dramas and comedies, but here the cutting is fast. The shots average 4.6 seconds by my count, which is about the same as the other Indiana Jones films (1). But whatever his shot length, Spielberg doesn’t resort to choppiness, the sort of image-snatching that typifies today’s mainstream cinema. He’s one of the few filmmakers working today (Shyamalan is another) who tries to give most shots a distinct arc—a beginning, a middle, and an end.

Granted, most shots in any movie will develop or progress, even if a character just steps forward or raises an eyebrow at the end of a spoken line. But Spielberg enriches his shots in the way that the old adage suggests: The only problem of direction is to prepare the audience for what is going to happen next.

The ambitious Spielberg shot starts with something that links precisely to a previous shot, then develops a visual or narrative premise of that, then ends with a firm point of information that carries us into the next shot. His main tools for building the shot are are spatial depth and camera movement.

Linking the shots, in multiple ways

In War of the Worlds. the protagonist Ray is hurrying toward the center of his neighborhood, where people are gathering. He passes a garage, where the mechanic Manny and his assistant are trying to fix a burned-out ignition. As Ray strides by, he suggests changing the solenoid, and Manny agrees. This becomes important later, when Ray will seize the vehicle because it’s the only civilian car that’s working.

Spielberg binds his shots together in this way. The end of the first shot shows Ray, along with others, hurrying to the left. Cut to a shot from inside the garage, with a silhouette in the foreground bending over a car’s engine. Ray becomes visible in the distance.

Ray’s appearance and reappearance link the shots, while Spielberg’s composition has prepared us for a dialogue between Ray and the man, as yet unseen, in the foreground. Cut to a moving point-of-view shot of Manny rising and turning to Ray (us) and explaining what has happened.

Reverse shot of Ray, still trotting along, over Manny’s shoulder as he suggests changing the solenoid. As he goes on, cut: The moving shot now detaches itself from Ray’s point of view and shows Manny ordering his assistant to change the solenoid. The assistant bends over the engine.

Cut to another driver bent over his engine. This reiterates the story point that everybody’s car has stopped, but it also echoes the end of the last shot (and the beginning shot of Manny in silhouette). Crane up slightly to pick up Ray walking leftward in the distance, an echo of the foreground/ background interplay of the Manny/ Ray shot.

How to develop this shot? We follow Ray, along with a skateboarder, to the intersection, where Spielberg introduces a new element. The shot gradually brightens and as Ray moves to the major intersection, rays of light wash out the image.

The next shot will repeat this pattern, from darkness to rays of light, so that the following shot can start with a burst of light that envelops Ray.

Then a new story component, involving Ray’s two buddies, comes in from the foreground. Their conversation with Ray will get a tracking shot devoted to it, but it will end with a story point….and so on.

Spielberg maps his story points quite precisely onto the beginning/ middle/ end of his shots so that they link smoothly with one another. Each camera movement or depth pattern leads to a distinct revelation, sometimes a fresh one, sometimes an expansion or specification of information we’ve already received. This is one reason he uses so many matches on action, even in simple dialogue scenes. The last bit of one shot can serve as the premise for the next if its movement can be carried over the cut.

Something extra between the shots