Archive for the 'Film archives' Category

Down in front! Notes from the Raccoon Lodge

O Brother, Where Art Thou?

There is one hypothesis that I find interesting because it is so minimal, yet sufficient. This is that nobody cares where he sits, as long as it’s not in the very front.

—Thomas Schelling, 1978

DB here:

Where do you like to sit in a movie theatre? If you’re like most people, you sit fairly far back, maybe all the way in the back row.

Sitting in the rear is the default for public gatherings, it seems. Thomas Schelling famously offered seven hypotheses about why people don’t fill up the front of an auditorium as fast as they fill up the back. His reflections were occasioned by his giving a lecture to 800 people, none of whom would sit in the first dozen rows. I know the feeling, though on a smaller scale. Seeing all your audience huddled so far away, you suspect you have cooties.

Schelling didn’t, so far as I can tell, offer a definitive answer, and his charitable reflections on people’s motives don’t keep me from finding the migration to the rear disquieting. In lectures, those distant auditors send off an air of foreboding. They seem poised to flee at the moment the talk reveals its fully catastrophic dimensions.

There’s a debate about whether students who sit in the rear get worse grades than those who sit close. (See below.) Speaking from experience, I’d be inclined to say that professors tend to give better grades to students sitting close because those distant, blurred ranks tend to give off an aura of desperate yearning to be anywhere but there. The folks up front at least seem to be trying to be part of things. The back-row brigade have not learned the great lesson of social life: Feign interest.

As this lead-in suggests, I’m a front-zone sitter. But that predilection comes at a cost.

Rebel without a Cause.

For lectures I always try to get a front-row seat, close to the speaker if possible, or centered if there’s to be a big visual presentation. This vantage point is great. If there’s flop sweat, you see it. If not, you get to enjoy consummate performance up close. I’ve sat in the front row for fine speakers like Chomsky, Pinker, and Bruner (to stay just with the Boston brain trust).

When a filmmaker does a Q & A, the front row is a must: you get a good chance at an autograph. The only time I regretted my prime front seat for a live event was for a concert—a John Zorn one. Within five minutes I expected my eardrums to bleed. After that overture I don’t think I heard anything else.

I saw back-row bias in the movies demonstrated dramatically in Madrid, where Tom Gunning and I went to a movie together. I forget the name of the theatre, but the film was Welcome to Veraz (1991), a Euroduction featuring, inevitably, Richard Bohringer and, less predictably, Kirk Douglas. Once we got inside, we found that our tickets were for specific seats. The cashier had assigned us, and all other patrons, to the same row—in the back, naturally. The absurdity of a dozen of us sitting side by side in a vast theatre was lost on the staff. Tom and I moved to the front, but everybody else piously stayed in the same pew.

You can study a less extreme case in graphic form in those remaining venues, mostly European and Asian, that still ask you to choose your seat on a chart. A glance shows you that everyone has piled into retreat mode, leaving lots of nice seats for you. Problem is, those overhead diagrams of the venue aren’t to scale, and so you don’t really know how close you are to the screen when you’re picking your seat.

When you were little, you didn’t mind sitting up by the screen. You sometimes fought to do it. But as we age, we seem to gravitate toward the rear. We’re even told that we should sit a prescribed distance back, usually the dead center of the auditorium. A distance of 2-3 times the screen height is a common recommendation. But Kristin and I are front-zone people. Speaking for myself, I like scanning the frame in great saccadic sweeps and even sometimes turning my head to follow the action. CinemaScope and Cinerama give your eyeballs a real workout.

I know that most people find this sheer madness. When the picture comes looming up, you do feel a little disconcerted and overwhelmed. But I find that I adapt in a minute or two. Even the keystoned angle isn’t a problem, partly because of our old friend perceptual constancy.

Note that I said front-zone. Not every theatre favors front-row sitting. Kristin and I once went to a screening of An Autumn Afternoon in a tiny Parisian house, one of those that seem to have been carved out of a loading dock. We sat in the front row, but that was a mistake. We could put our feet up against the wall housing the screen, and we reckon we watched the movie at something like a 45-degree angle.

Something a little more peculiar happened when we went to a Fan Preview of Scott Pilgrim vs. the World. Firmly ensconced front and center, we were packed in by comic geeks, nerds, dorks, wonks and other damned souls, all determined to enjoy this movie. So we had the strange experience of hearing a line of dialogue and then, because its eloquence had a rich bouquet, hearing yelps of appreciation rolling back behind us, as row after row (a) heard it, (b) laughed, and (c) did an instant commentary on it. I can’t judge this movie objectively to this day.

So sometimes the front row isn’t ideal. Through experience, we know our local venues and favorite festival sites. In some theatres, such as most of our local Sundance screens, we sit 2-5 rows back, with C being a common choice. Still, the ticket seller usually does a double take and reminds us where the screen is. Then we get a shrug and something on the order of “Well, you won’t be crowded down there.”

Bologna Cinema Ritrovato 2008: Olaf Möller, Jonathan Rosenbaum, Don Crafton, Haden Guest, Kristin Thompson.

But in many venues the front row is perfect. Sitting there is hard-core moviegoing. I started aiming for it about forty years ago, when I began taking notes on every film I saw. If you sit too far back, how can you see your pad? You can’t be one of those idiots brandishing a lightbulb pen (even though I have some of those). The screen casts a little light that makes scribbling easier.

But even those who don’t write notes see the advantage of the front row. Nobody’s head looms in front of you. You’re less disturbed by latecomers. You have more leg room, and it’s easier to stretch out for a snooze. And should you wish to leave, the front row is the only one that lets you sneak out easily from any seat.

That last advantage, I should mention, can lead to trouble. Once at VIFF I was firmly planted in the front row, nose in book, as the auditorium filled. But I began to realize that these didn’t seem to be my tribe. There were more beards, nicer clothes, better hygiene, more sensitive faces. The place filled, and someone came forward to thank the sponsors for bringing a film about the efforts to save remote wetlands. I was in the wrong auditorium. To glares and mocking comments I slunk out in search of some obscure art movie I’ve forgotten.

Like everything else you do, front-row sitting sends a message. What message? For one thing, that signal of interest I mentioned in my classroom example. Somehow the front-row sitter seems to be more engaged, more eager to be swept up in the magic. You probably know the urban legend that the Cahiers du cinéma writers sat devoutly in the front row at Langlois’ Cinémathèque. We belong to a noble tradition, and we flaunt it. Chevaliers of cinéphilie, we risk eyestrain, neckache, back pain, and leg cramps for the art of cinema, or so we like to think.

Speaking of the Cinémathèque, back in 1970 I went to the Chaillot venue for a screening of Liebelei, to be attended by Luise Ullrich, one of the principal players. The place was full, but I had nabbed a nice spot up front. Before the film started, though, a Cinémathèque functionary started going along the front row asking every patron there a question. Everyone asked said no. I couldn’t hear the question at a distance, and perhaps might not have understood it if I had. So when the staff member came to me, I scarcely let him finish before declining. If non was good enough for other front-row denizens, it was good enough for me.

After the lights came down, Henri Langlois stepped onstage with Mme Ulrich. After a brief introduction, they descended. Only then did two people on the aisle surrender their seats for them. Then I realized all the French guys sharing the front row with me wouldn’t give up their seats even for the guest and the boss of it all. You see why I say front-row people are hard-core?

Le Pied qui étreint 1: Le Micro bafouilleur sans fil (1916).

I must report, however, that front-row sitting sends other signals too. Theatres in film archives have their regulars, and these folks, like me, believe that there’s only one good seat in any theatre, and they must occupy it. Fortunately, they mostly don’t agree on what that seat is. I’m always befuddled when the first person in the queue makes a dive for a seat far back and in the corner.

Alas, though, so many regulars have aimed at my target that every cinematheque has a coterie of front-row fans. And they’re perceived as, well, strange. I remember going to London’s National Film Theatre during a visit and getting in early enough to nab a prime front seat. Many regulars shuffled in to join me, and one seemed a bit miffed after the rank had filled. My neighbor told me apologetically that I was sitting in his friend’s seat. Of course I moved. Local loyalists have privileges. On another occasion a BFI staff member said that she worried that one of her friends might become “one of those sad front-row people at the NFT.” They didn’t seem unusually unhappy to me, but then they wouldn’t, for I am one of them.

My strangest contretemps with a front-row devotee came during a visit to the Munich archive. They were running Get Carter and I was the first entrant. I secured my front-row center post and settled down to read. (Front-row people show up early enough to finish substantial portions of Dostoevsky novels before the lights go down.) Suddenly an aged German lady, fortunately not Luise Ullrich, stood before me.

Seeing I was reading a book in English, she said, “Pardon me, you’re in my seat.”

I looked around and saw that we were the only people in the theatre.

“I always sit here,” she said. “I come every night.”

Nerdesse oblige. I relocated to the seat behind her. Moved by my gallantry, she twisted around to talk with me. I asked if she really came every night.

“Well, not every night. Not if they’re showing a Jap movie.” She looked severe. “I don’t like Japs.”

Comments about disloyalty to old friends leaped to my tongue, but I kept quiet.

Soon Get Carter started. The old bat immediately fell asleep.

She slept through the whole movie. I wanted to knock her upside the head. When I left, she was still out, snoring in my seat.

There are other drawbacks to the avant-garde spot in the movie theatre. Most people are bothered by handheld shots and 3D if they sit close, but I don’t find myself affected. Granted, I probably miss some of the surround-sound effects, which are apparently designed for a sweet spot far behind my territory. If it’s any compensation, the left/ right channels are really vivid for me.

The biggest drawback, though, is that you don’t have eyes in the back of your head. During Q & A sessions, you can’t track the conversation without twisting around in your seat. So I sit there as if I were listening to the radio. Worse, sitting close can render you oblivious to things going on behind you. If a fistfight broke out in that heavily populated rear section, you’d be in a poor position to watch it. Occasionally being in the front row makes me miss an outburst that was probably pretty entertaining but leaves me feeling like the guy in Pompeii who wondered why everybody was running past him just before a couple of tons of ash buried him.

A Drunkard’s Reformation (1909).

On the obliviousness scale, my most memorable front-row experience came during another overseas festival. A visiting actress of consequence had directed some feature-length films, and the festival had arranged a screening of one. This entailed setting up a video projector and preparing, far in advance, electronic subtitles in the local language. When the director saw me planted in the pole position she said, “You shouldn’t sit so close. This movie is like Dancer in the Dark.”

No problem, I assured her; I’d seen that from the front row too.

No one joined me in the front. But there was a sizeable audience. Once people had settled down, her introduction explained five things, each one adding to a litany of doom.

(1) She played the protagonist.

(2) The film was improvised.

(3) It was shot handheld.

(4) The actors were her friends.

(5) It was a satire on the superficiality of Los Angeles life.

She wished us a good screening and said she’d see us afterward for a discussion.

The film was as dire as I’d feared. When the lights came up I noticed that nobody was setting up the microphone on stage. I turned around. The technicians were putting away the projection equipment. I was the only viewer who’d hung on to the end. Needless to say, there was no auteur and no Q & A.

Despite all the drawbacks of front-zone sitting, I feel vindicated by a recent revelation. A review quotes James Wolcott’s acount of Pauline Kael’s preferred viewing station.

We take up mortar position in the back row. Pauline nearly always sits in the back, often right beneath the projectionist’s portholes, flanked by fellow critics on her squad. . . . (The auteurists — those ardent members of Andrew Sarris’s Raccoon Lodge — tended to huddle closer to the screen, as if to meld mind and image into a blissful, shimmering mirage of Kim Novak with her lips parted.)

I rest my case.

Thomas Schelling’s reflections on lecture-hall seating open his classic Micromotives and Macrobehavior. Among his more entertaining speculations on why people sit in the back is this one:

A fourth possibility is that everybody likes to watch the audience come in, as people do at weddings.

For some research on whether students sitting up front get higher grades, go here (abstracts only) and here. Jonathan Cohen provides a nice analysis of the research on perceptual constancy here. 3D has rekindled debates about where to sit; for one exchange among cinematographers, go here.

Le Pied qui étreint is discussed in more detail here.

Joe Dante at University of Wisconsin–Madison, November 2011. Photo by Jeff Kuykendall. For more on Dante’s visit, go to this earlier entry and to Jeff’s coverage here.

PS 23 January 2012: Please note that another couple likes to sit in the front row (from here).

Ledoux’s legacy

DB here:

Every summer Brussels hosts one of the world’s most unusual film festivals. By global standards it’s a small event: it showcases only twenty or so titles, each screened twice. The films are on the whole unknown. The prizes are minuscule by the million-plus benchmarks set by Dubai and Abu Dhabi. The venue stands behind an inconspicuous doorway. Yet for me it’s an unmissable event, a crucial influence on my thinking about film and my search for cinematic satisfaction.

Jacques the gentle

Young Murderer (Seishun no satsujin sha, 1976).

Between 1948 and his death in 1988, Jacques Ledoux was the curator of the Royal Film Archive of Belgium. He made it into one of the cinema’s legendary places, at once Mecca and Aladdin’s cave. On remarkably small budgets, he assembled broad and deep collections. He bought many titles for distribution to local cinemas and schools. He created a public screening program that for decades has shown five different films (two of them silents), every day of the year. The year Ledoux died he received an Erasmus Prize for his services to European culture.

His early life could have come out of an East European movie. Born in Poland in 1921, he fled to Belgium to escape the German onslaught. He hid in several places, including a monastery. There the abbot gave him work publishing Benedictine books. In the abbey’s screening room Ledoux discovered a copy of Nanook of the North. He offered it to the just-started Belgian Cinémathèque, and its supervisor, the filmmaker Henri Storck, offered Ledoux a job. Finding film archivery more appealing than studying science and medicine, he stayed with the Cinémathèque. Interestingly, “Jacques Ledoux” was a pseudonym; one translation is Jacques the Gentle.

Not always gentle Jacques in his scraps with other archivists and local politicians, Ledoux pledged himself to filmmakers, audiences, and—a rarity at the time—overseas film scholars. New Wave directors and Parisian critics made railway pilgrimages to Brussels to see films unavailable in France. When Kristin and I started doing research in the archive in the 1979, Ledoux welcomed us and guided us to treasures we hadn’t known existed.

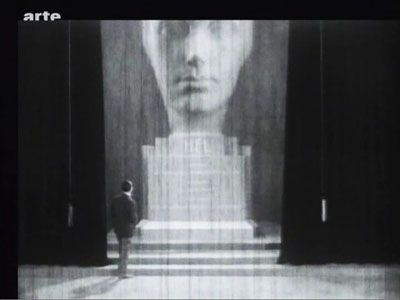

Unlike the very public Henri Langlois, Ledoux worked best behind the scenes. Probably most cinephiles today know him only from his brief appearance as one of the sinister experimentalists in La Jetée (1961). He resisted being photographed, and he refused to wear a necktie. Unsurprisingly, he admired directors who strayed from the beaten path. He created the first festival of experimental cinema at Knokke-le-Zoute, in 1949.

Unlike the very public Henri Langlois, Ledoux worked best behind the scenes. Probably most cinephiles today know him only from his brief appearance as one of the sinister experimentalists in La Jetée (1961). He resisted being photographed, and he refused to wear a necktie. Unsurprisingly, he admired directors who strayed from the beaten path. He created the first festival of experimental cinema at Knokke-le-Zoute, in 1949.

His desire to widen everyone’s knowledge of cinema found another outlet when he created the Prix l’Age d’or/ Prijs l’Age d’or in 1958. It was aimed to reward, as Ledoux put it, “a film that, by questioning taken-for-granted values, recalls the revolutionary and poetic film of Luis Buñuel, L’Age d’or.” Ledoux wanted to encourage a cinema that was subversive in both content and form.

The first prizes were given within the framework of the Knokke event: in 1958, to Kenneth Anger; in 1963, to Claes Oldenberg; in 1967 to Martin Scorsese (for The Big Shave). In 1973, the prize assumed something close to its current form. Several films were screened for the public, and the award, now in the form of cash, was decided by a jury system. The first winners were W. R.: Mysteries of the Organism (in 1973); Borowczyk’s Immoral Tales (1974); Raul Ruiz’s Expropriation (1975); Angelopoulos’ Traveling Players (1976); Hasegawa Kazuhiko’s Young Murderer (1977); and Antoni Padros’ Shirley Temple Story (1978).

The winners emerged from a vast and powerful field of competition. In 1973, the first formal year of L’Age d’or, there were sixty-nine films screened, including Aguirre, the Wrath of God, Oshima’s Ceremonies, Paul Morrissey’s Heat, Tout va bien, and works by Rosa von Praunheim, Wim Wenders, and Miklós Jancsó. There was even The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie, but Buñuel didn’t win a prize named after his own film! The number of titles dropped a little as the years passed, but it’s good to know that in 1978 Assault on Precinct 13, Eraserhead, Perceval le Gallois, and films by Ruiz, Littín, and Schroeter were in the competition.

Ciné-Discoveries

City of Sadness (Hou Hsiao-hsien, 1989); screened at Cinedécouvertes 1990.

Things changed a bit after 1979. The L’Age d’or criteria were modified to identify “films that by their originality, the singularity of their viewpoint, and their style [ecriture] deliberately break from cinematic conformity.” For whatever reasons, hard-edged subversive cinema was harder to come by. In the meantime, the Prix was absorbed into a broader festival Ledoux launched in 1979, Cinédécouvertes.

Cinédécouvertes became a “festival of festivals.” It culled its selection from films that had been screened at Rotterdam, Berlin, Cannes, Venice, and other events. What set Cinédécouvertes apart was its determination to expand film culture. All the films on the program had no Belgian distribution. Each cash award (today, two of 10,000 euros each) would go not to the filmmaker but to a distributor willing to pick up the film. This is a very tangible way to help films of quality find a local audience.

Over the last ten years, Cinédécouvertes has awarded prizes to Audition, Chunhyang, Werckmeister Harmonies, Oasis, Tropical Malady, Day Night Day Night, Mogari no Mori, Afterschool, and Police, Adjective. The L’Age d’or prize has been given to Aoyama’s Eureka, Reygadas’ Japón, Encina’s Hamaca Paraguay, Balabanov’s Cargo 200, and several others. Not every film has been picked up for local distribution, but the impulse to elevate films that go beyond the obvious festival favorites has continued. Ledoux’s successor as curator, Gabrielle Claes, has maintained the legacy of L’Age d’or and Cinédécouvertes. The July festival flourishes in the Cinematek’s newly rebuilt complex and in its other venue, the lovely postwar-moderne building in the Flagey neighborhood.

The annual Brussels event helped me find my way through modern cinema. There I saw my first Kiarostami (Where is My Friend’s Home?), my first Tarr (Perdition), my first Hou (Summer at Grandpa’s), my first Oliveira (No; or, the Vainglory of the Commander), my first Sokurov (The Second Circle), my first Kore-eda (Maborosi), my first Panahi (The Mirror), my first Jia (Xiao Wu). The Cinematek’s talent-spotters were quick to find many of the most important filmmakers of the 1980s and 1990s, and I’ll be forever grateful for their acumen. After I saw these films and many others here, my ideas about cinema got more cogent and complicated. My life got better, too.

Now most of these filmmakers find commercial distribution in Belgium, so Gabrielle’s scouts must scan new horizons. This year as usual Cinédécouvertes boasted some familiar names like Iosseliani, Wiseman, Guzman, and the eternal troublemaker Godard. But there are also filmmakers from Costa Rica, Sri Lanka, Ireland, Peru, Colombia, and Ukraine. The landscape of film is vast, as Ledoux always reminded us, and a small festival can nonetheless open windows wide.

Mind games, or just games

Elbowroom.

Psychology is at the center of festival cinema. Deprived of car chases and exploding buildings, arthouse filmmakers try to track elusive feelings and confused states of mind. That this can be dramatically engaging in quite a traditional way, as was shown by one of the Cinédécouvertes winners, How I Ended This Summer.

Director Aleksei Popogrebsky puts two men on a desolately beautiful island in the Arctic. They’re initially characterized by the way they execute the routines of measuring weather conditions. Sergei, the stolid older one, is soaked in the ambience of the place, enjoying fishing and boating while insisting on exactness in the log. Pasha is a summer intern, a little careless because he’s exhilarated by the atmosphere: he’s introduced first taking a Geiger-counter reading but then hopping and racing along a cliff edge to the beat of his iPod.

Soon, though, Pasha must give Sergei a piece of bad news that comes in over the radio. Out of awkwardness, fear, refusal of responsibility, and other impulses, he avoids telling his mentor. The consequences are unhappy for each. The film takes on the suspense of a thriller, with conflicts surfacing in a cat-and-mouse game at the climax. Yet before that, more subtly, we have watched several tense long takes of Pasha’s face as he tries to cover up his failures. Not surprisingly, How I Ended This Summer won one of the two Cinédécouvertes prizes. It is an engrossing case for character-driven, locale-sensitive cinema.

Elbowroom tackles psychology from a more opaque and disturbing angle. With no exposition or backstory, we’re plunged into an institution for the handicapped. During the first ten minutes, without dialogue, a handheld camera lurks over the shoulder of a young woman who tries with twisted fingers to apply lipstick. Soon she is preparing to have sex with another inmate, and after their liaison she is whacking her feeble roommates, who sob under her blows. Eventually we’ll recognize this introduction as a summary of her days: fighting with others, being coaxed or berated by staff, meeting her lover, and taking up cleaning tasks. Only far into the film will we learn about how she got here and what her fate will be.

Soohee, stricken with cerebral palsy, is played by a young woman with a milder disease. Very often the camera doesn’t let us see her face, fastening instead on a ¾ view from behind. This seems to me partly a matter of tact, but its ultimate effect is to force us to infer Soohee’s state of mind from her behavior. The visual narration remains resolutely outside the character. Psychology gets reduced to gestures— spasmodic smearing of lipstick, the clasping of a necklace, the seizure of a baby doll (with which she’s bribed). Only at the end does a long held close-up of Soohee’s twitching, smiling face give us fairly direct access to her feelings. Despite the smile—which can be read as a sort of perverse victory for her—Soohee isn’t the noble victim; we’ve seen her petty and selfish side already.

This trip into a world most of us haven’t seen before is presented without conventional pieties, and it’s unsettling. Elbowroom, Ham Kyoung-Rock’s first feature, offers the sort of challenge to aesthetic and moral conventions that the L’Age d’or Prize was designed to encourage. The film won it.

Characters’ psychological developments can also be brought out by parallel construction. A willful little girl and a scientist cross paths in Paz Fábrega’s Cold Water of the Sea. Karina is on a beach holiday with her family and insists on wandering off at intervals. Marianne is a medical researcher, here for a vacation with her boyfriend. When Marianne finds Karina asleep along the road one night, the girl claims that her parents are dead and that her uncle abuses her. But next morning she’s gone, and fears for her safety are only the first of several anxieties that haunt Marianne’s holiday. While Karina incessantly bedevils her mother and makes mischief with other kids, Marianne descends into ennui as she watches her boyfriend devote his time to selling a piece of family property.

Characters’ psychological developments can also be brought out by parallel construction. A willful little girl and a scientist cross paths in Paz Fábrega’s Cold Water of the Sea. Karina is on a beach holiday with her family and insists on wandering off at intervals. Marianne is a medical researcher, here for a vacation with her boyfriend. When Marianne finds Karina asleep along the road one night, the girl claims that her parents are dead and that her uncle abuses her. But next morning she’s gone, and fears for her safety are only the first of several anxieties that haunt Marianne’s holiday. While Karina incessantly bedevils her mother and makes mischief with other kids, Marianne descends into ennui as she watches her boyfriend devote his time to selling a piece of family property.

Once more Rossellini’s Voyage to Italy proves to be a template for festival cinema. What is wrong with Marianne goes beyond her diabetes: she feels bored and useless. But while Rossellini adhered primarily to the viewpoints of his dissolving couple, Fabrega opens out the portrayal of upper-class anomie by intercutting episodes from the lives of working-class families. The film has two fully-developed protagonists, with Karina’s verve balancing Marianne’s increasing torper. Splitting his story allows Fabrega to make some social points (the family camps on the beach, the couple stays in a motel with a scummed-over swimming pool) and to suggest secret affinities between the little girl and the professional woman. Cold Water of the Sea seemed to me an honorable effort to let some air into the premises of the standard portrayal of a cosmopolitan couple’s ennui.

Parallels likewise form the core of Otar Iosseliani’s Chantrapas, another of his celebrations of shirkers, layabouts, con artists, and free spirits. The title is Russian slang for a disreputable outsider (derived from the French ne chantera pas, “won’t sing”). Here the outsider is Kolya, a young Georgian director who turns in a movie that can’t pass the censors. He emigrates to Paris, where he finds an aging producer (played by Pierre Etaix) eager to tap his talent. But the new project’s backers try to take over the project in scenes deliberately echoing the ones of Party interference.

Chantrapas lacks the shaggy intricacy of Iosseliani’s “network narratives” like Chasing Butterflies (1992) and Favorites of the Moon (1984), the latter of which I enjoyed analyzing in Poetics of Cinema. When we’re given a single protagonist, as in Monday Morning (2002), Iosseliani’s characteristic refusal of motivation, exposition, and introspection creates a more plodding pace. No mind games here. In earlier films, his favorite shot—panning to follow people walking—creates convergences and near-misses and comic comparisons in the vein of Tati. Here the pans serve as merely functional devices, almost time-fillers, and comedy is largely lacking. Still, Iosseliani avoids the easy traps. A Soviet censor bans Kolya’s film, then congratulates him on making such a good movie. When the Parisian preview audience flees the theatre, we can’t call them philistines. Kolya’s movie, despite its stylistic debt to Iosseliani’s own films, looks awful. In the end, even cinema seems less important than smoking, drinking, eating, and, above all, loafing.

It was a documentary, Nostalgia de la Luz by Patricio Guzmán, that won the second Cinédécouvertes prize. It starts as a memoir of Guzmán’s fascination with astronomy, explaining that the unusually clear skies of Chile have attracted researchers who want to probe the cosmos. Because the light from heavenly bodies takes a long time to reach us, Guzmán casts his observers as archeologists and historians: “The past is the astronomer’s main tool.” This is the pivot to the film’s main subject, the search for the disappeared under the US-installed dictator Pinochet.

The analogies rush over us. The enormity of the universe is paralleled by the immensity of Pinochet’s oppression of his country. Captives in desert concentration camps learned astronomy, but eventually they were forced inside at night; the skies’ hint of freedom threatened the regime. Some of the astronomers are friends or relations of the disappeared and see research as therapeutic, putting their personal sufferings in a much more vast cycle of change. Above all there are the old women who patiently scour the desert for traces of their loved ones. A woman tells of finding her brother’s foot, still encased in sock and shoe. “I spent all morning with my brother’s foot. We were reunited.” Scientists try to know the history of the cosmos, and ordinary people tirelessly challenge their government’s efforts to conceal crimes. Both groups, Guzmán suggests, acquire nobility through their respect for the past.

Taking some chances

More formally daring was Totó. This was the first Peter Schreiner film I’ve seen, and on the basis of this I’d say his high reputation as a documentarist is well-deserved. Without benefit of voice-over explanations, we follow Totó from his day job at the Vienna Concert Hall (is he a guard or usher?) to his hometown in Calabria. The film is an impressionistic flow registering his musings, his train travel, and his conversations with old friends, many of the items juggled out of chronological order.

Schreiner avoids the usual cinéma-vérité approach to shooting. Instead the camera is locked down, the framing is often cropped unexpectedly, and the digital video supplies close-ups that recall Yousuf Karsh in their clinical detail. We see pores, nose hair, follicles at the hairline; the seams of sagging eyelids tremble like paramecia. In addition—though I won’t swear that Schreiner controlled this—the subtitles hop about the frame, sometimes centered, sometimes tucked into a corner of the shot, usually with the purpose of never covering the gigantic mouths of the people speaking. All in all, a documentary that balances its human story with an almost surgical curiosity about the faces of its subjects. The Jean Epstein of Finis Terrae would, I think, admire Totó.

I had to miss some of the offerings, notably Oliveira’s Strange Case of Angelica. (Fingers crossed that it shows up in Vancouver.) Eugène Green’s Portuguese Nun was screened, but I’ve already mentioned it on this site. Other things I saw didn’t arouse my passion or my thinking, so they go unmentioned here. Of the remainders, two stood out above the rest for me.

My Joy (Schastye moe), by Sergei Loznitsa, is a daring piece of work. After a harsh prologue, it spends the first hour or so on Georgy, a trucker whose effort to make a simple delivery takes him into the predatory world of the new Eastern Europe. He meets corrupt cops, a teenage hooker, and most dangerously a trio of ragged men bent on stealing his load. After an anticlimactic confrontation, the film introduces a fresh cast of characters, including a mysterious Dostoevskian seer. The film becomes steadily more despairing, culminating in a shocking burst of violence at a roadside checkpoint.

At moments, My Joy flirts with the idea of network narrative. When Georgy turns away from a traffic snarl, the camera dwells on roadside hookers long enough to make you think that they will now become protagonists. One character does bind the stories together: an old man who fought in World War II and who now helps the seer at a moment of crisis. The sidelong digressions, slightly larger-than-life situations, and the floating time periods suggest a sort of Eastern European magic realism. But the whole is intensely realized, at once fascinating and dreadful. After one viewing, I wanted to see it again.

My favorite, as you might expect, was Godard’s Film Socialisme. There are the usual moments of self-conscious cuteness (the zoom to the cover of Balzac’s Lost Illusions, for instance), but on the whole it’s pretty splendid.

Contrary to what a lot of people claim, I don’t think Godard is an “essayist” in most of his films. (Perhaps in Histoire(s) du cinema, but rarely elsewhere.) He tells stories. Granted, they are elliptical, fragmentary, occulted stories, free of expository background and flagrantly unrealistic in their unfolding. Into these stories he inserts citations, interruptions, digressions: associational form gnaws away at narrative. But stories they remain.

The first part of Film Socialisme takes place on a cruise ship. As it visits various ports on the Mediterannean, some passengers learn that a likely war criminal is on board. Then, like Loznitsa, Godard shifts to a new plot. In the French countryside, a garage-owner’s family is invaded by a TV crew. (As far as I can tell from the untranslated dialogue, the son and daughter are purportedly running for elective office.) Finally, in the last eighteen minutes or so, we get pure associational cinema—not an essay, I think, but something like a collage-poem: a busy montage of clips seeking (or so it seems to me) to ask what sort of European politics is possible after the death of socialism.

Andréa Picard has already written a superb commentary on the film, and it would be useless for me, after only two viewings, to try to go much beyond her account. I’d just say that the first two stories show the same sort of ripe visual imagination we have come to expect from late Godard. The images are oblique and opaque, framed precisely but denying us much in the way of story information. Who are these people? Who’s related to whom? (Who are the women apparently linked with the mysterious Goldberg?) More concretely, who’s talking to whom?

Godard cuts among images of varying degrees of definition in a manner reminiscent of Eloge de l’amour, but here color is paramount. We get saturated blocks of blue sky and blue/ turquoise/ charcoal sea. See the image further above, or this one, which is virtually a perceptual experiment on the ways that color changes with light and texture.

Anybody with eyes in their head should recognize that such shots show what light, shape, and color can accomplish without aid of CGI. They aren’t simply pretty; they’re gorgeous in a unique way. No other filmmaker I know can achieve images like them. We also get entrancing scatters of light in low-rez shots in the ship’s central areas and discotheque.

Just as noteworthy from my front-row seat was Godard’s almost Protestant severity in sound mixing. For the first twenty minutes or so, the sound is segregated on the extreme right and extreme left tracks, leaving nothing for the center channel. We hear music on the left channel and sound effects on the right, or ambient sound on one side and dialogue on the other. The result is a strange displacement: characters centered in the screen have their dialogue issuing from a side channel. Sometimes a sound will drift from one channel to another and back again, but not in a way motivated by character movement (“sound panning”). Having accustomed us to this schizophrenic non-mix, Godard then starts dropping a few bits into the center channel. But for the bulk of the shipboard story, that region is largely unused.

We leave the ship with a title, “Quo Vadis Europa,” and now we’re in Martin’s garage, listening to him being interviewed by an offscreen woman. His voice squarely occupies the central channel, with offscreen traffic sliding around the side channels. The same central zone is assigned to the wife and the kids. Would it be too much to say that the working people have taken control of the soundtrack? In any case, although the side channels are very active, the sound remains centered during a permutational cluster of family scenes (parents and children alone, father with daughter, mother with son, boy with father, daughter with mother).

This section ends with a final confrontation with the nosy reporters. The overall episode can be seen as a revisiting of Numero deux (1975), another uneasy family romance and one of Godard’s first forays into video.

The rapid-fire finale would require the sort of parsing that Histoire(s) du cinema has invited. Through footage swiped from many other filmmakers, Godard revisits the cruise ship’s ports of call, investing each with a symbolic role in the history of the West. Egypt and Greece get considerable emphasis, but so do Palestine and Israel. This history is, naturally, filtered through cinema: not just footage of the Spanish Civil War but clips from fiction films like The Four Days of Naples (1962). After glimpses of Eisenstein’s Odessa Steps massacre, we get shots of today’s kids standing on the steps declaring they have never heard of Battleship Potemkin.

Exasperating and exhilarating, Film Socialisme shows no flagging of its maker’s vision. “He’s a poet who thinks he’s a philosopher,” a friend remarked. Or perhaps he’s a filmmaker who thinks he’s a painter and composer. In any case, Film Socialisme will be remembered long after most films of 2010 have been forgotten. More intransigent than most of his other late features, and unlikely to be distributed theatrically outside France, if there, it shows why we need “little” festivals like Cinédécouvertes now more than ever.

The home page of the Cinematek is here. A complete list of L’Age d’or and Cinédécouvertes winners is here. Last year, between research and preparing for Summer Movie Camp, I had no time to blog about the festival. But you can go to my earlier coverage for 2007 and 2008.

As one who cares about Godard’s aspect ratios, it pains me to use illustrations from online sources, which are notably wider than the version I saw projected in Brussels. When I can get my hands on a proper DVD version, I will replace these images with ones of the right proportions.

Seeing movie seeing: Display monitors in the reception area of the Cinematek.

More cinema Bolognese

Josette Andriot, decked out for Protéa.

Kristin here, with more from Cinema Ritrovato in Bologna:

When one thinks of female masters of disguise and action in the silent cinema, Musidora as Irma Vep in Feuillade’s Les Vampyrs probably springs first to mind. But for the historian, hovering always in the background was the legendary film by Victorin-Hippolyte Jasset, Protéa (1913), with Josette Andriot in the lead role. We knew the film mainly from a frequently reproduced image of the heroine in a black outfit, one of many she wears in the film.

Andriot was unconventionally beautiful, with dark hair and eyes and strong rather than delicate features. She was a genuine athlete, hired initially by Jasset for her riding ability, though he later exploited her acrobatic abilities in chases and scrambles around buildings.

Andriot was unconventionally beautiful, with dark hair and eyes and strong rather than delicate features. She was a genuine athlete, hired initially by Jasset for her riding ability, though he later exploited her acrobatic abilities in chases and scrambles around buildings.

Protéa has now been restored, though there is still missing footage. The heroine’s partner is Lucien Bataille, looking rather like a particularly devious James Cagney in the role of L’Anguille (“The Eel”), whose quick-change abilities and athleticism match hers. The thin, episodic plot revolves around a classic Macguffin, a treaty between two imaginary, vaguely Eastern European countries. The pair must acquire the document and hold onto it through one danger after another, outnumbered and chased all the while by a ruthless gang of spies for the other side.

I was startled by how modern the film seemed. Critics today tend to claim, inaccurately, that big action films throw some big thrill at the audience every few minutes. Protéa really does. The underlying purpose of the plot is to have the two leads escape from one sticky situation and change disguises, only to land immediately in another sticky situation. It’s essentially a serial boiled down into a feature.

The term “cinema of attractions” was originally coined by Tom Gunning to describe very early films that depended on novelties rather than narratives. These days, many academics apply the phrase to almost any film, old or new, boasting a lot of action and big special effects. But I’m tempted to use it of Protéa anyway. Jasset usually doesn’t keep Protéa and L’Anguille in any one disguise or situation long enough to exploit the initial premise. One moment she’s pretending to be a man; next thing we know, she’s an elegant partygoer and L’Anguille is a servant. The basic problem is that whenever the characters get into trouble, they don’t rise to the occasion by exploiting their current roles more cleverly. They just flee and assume a new disguise to try again. As a result most of the individual episodes remain unmemorable.

One exception is a sustained sequence showing the couple as traveling animal trainers. At one point they crawl into the cage and play with a real lion, and they stay in these disguises long enough to actually use the big cats to fend off their pursuers. The final hectic chase, with Protéa on a bicycle fleeing toward a bridge set aflame by the villains, is the most impressive passage we can enjoy as sustained action. (I won’t reveal how it comes out, except to say that the climactic moment prefigures a modern action heroine driving a bus toward a gap in an unfinished freeway.)

Protéa is fun, in large part due to the talent of the two leads. It’s a pity that this was Jasset’s penultimate film. He died in hospital before it was released. (His last film, La Danseuse de Kali, also starring Andriot, was recently rediscovered by our friend Hiroshi Komatsu and was shown in this year’s festival.) Perhaps Jasset would have developed into one of the major directors of serials. Still, one can see why Feuillade, who knew how to build suspense by stretching out a scene’s action, became the French master of the form.

Etaix Refurbished

In an earlier entry, I mentioned that for some years French comic director and actor Pierre Etaix had not controlled the rights to his own films (two shorts and six fiction features). During that time, they were out of circulation and unavailable in any format. That situation has finally been rectified. Etaix has recovered the rights, and all the films have now been restored. They were re-premiered earlier this year at Cannes, and two were included in Il Cinema Ritrovato: the short Heureux anniversaire (1962) and the feature Le grand amour (1969).

Etaix’s early work in the cinema was during the 1950s as an assistant to Jacques Tati, and he is widely seen as having been greatly influenced by Tati. That’s true to some degree. In Le grand amour there are gags using sudden peculiar noises. Although the plot centers around the hero Pierre, his wife Florence, and his in-laws, there are nosy neighbors and waiters through whose eyes we are occasionally asked to view the action. When Pierre’s friend gives him instructions on how to behave on an upcoming date with his pretty secretary, bar patrons assume that they’re witnessing two gay men flirting.

Still, Etaix’s general approach is not particularly Tatian. He does not play a continuing character from film to film. In Le grand amour, as the young husband lured into managing his father-in-law’s factory, he dresses in conservative suits and casual wear; no Hush Puppies, striped socks, and too-short raincoat for him. Pierre succeeds in his dull job, unlike Hulot, who makes a mess of things when given a low-level job at his brother-in-law’s factory. The neighbors watch Pierre not because he is eccentric, but because they jump to wrong conclusions about his mundane behavior.

More importantly, though, Le grand amour creates a great deal of its humor with a technique that Tati would never use. He frequently shows hypothetical alternatives to the scene at hand. What if Pierre’s sophisticated friend were married to Florence? We see a scene played out with the friend in his place. There is a dream in which Pierre’s bed drives like a car along a country road, encountering other bed-cars and finally picking up the new secretary, hitchhiking by the road. When Pierre finally dares to take the secretary out to dinner, he launches into a nervous, boring monologue on business prospects, and we see him as she does, successively older and grayer with each reverse shot. When the gossipy neighbors pass along a story about Pierre, we see the successively exaggerated versions played out one by one, from the reality in which he merely tips his hat to a pretty woman he passes in a park through overt flirting to a passionate encounter behind a bush.

Le grand amour is not as funny as Tati’s films, but that probably results from an explicit melancholy that underlies this tale of disillusionment with marriage and final acceptance of the realities of life-long love. At times it reminded me more of the playful moments in Truffaut, especially in Shoot the Piano Player. Whether or not one wants to place Etaix in the New Wave, his play between reality and fantasy would seem to put him in the category of “ludic modernism” that Malcolm Turvey spoke about in his paper at the recent Society for the Cognitive Study of the Moving Image conference.

The restored print was beautiful, with the kinds of bright and pastel colors and high-key lighting that one seldom sees in the drab films of today. Presumably the new copies will show at other festivals and in art-houses with DVD releases to come.

Cinephiles’ corner

Bologna brings out a bevy of critics, historians, programmers, and unabashed film lovers of all stripes. Herewith, a sampling from DB.

Two critics for the ages: Kent Jones of Physical Evidence and the World Cinema Foundation, alongside Joe McBride, author of books on Ford, Capra, Welles, and Spielberg.

Dick Abel and Virginia Wright Wexman, both distinguished scholars, flank a copy of Dick’s book, French Cinema: The First Wave–presumably kept under glass like the rare specimen it is.

Curatorial cuddling: Haden Guest of the Harvard Film Archive, Adrienne Mancia retired from MoMA (and once a UW Badger).

The Cottafavi Cult invictus: Critics and programmers Barbara Wurm, Olaf Möller, and Christoph Uber, always in the front row.

Camille Blot-Wellens, director of Film Collections at the Cinémathèque Française tells Danish historian Casper Tybjerg of her restoration of Albert Capellani’s Chevalier de Maison-Rouge (1914).

Two walking film encyclopedias sitting down: Kevin Brownlow, pioneer British historian, director, and collector, and Lee Tsiantis of Turner Classic Movies.

David Meeker, master of British cinema and jazz on the screen; Matthew Bernstein, author of Walter Wanger, a study of the Leo Frank lynching, and other studies of film history and culture.

Mariann Lewinsky, heroic programmer of the 1910 series and the Capellani retrospective, introduces Nikolaus Wostry, of Filmarchiv Austria.

More to come in at least one more Bologna-based entry!

METROPOLIS unbound

Fritz Lang has created a lot of pretty pictures and has discovered the astonishing talent of Brigitte Helm. I cannot blame him for not being able to cut the quantity of ideas in individual scenes mercilessly enough (the water catastrophe, the duel), but instead repeatedly trying out new lighting and angles. This time the film’s qualities lie precisely in these efforts: and if the viewer knows how to make the best of something, he will derive pleasure from these images.

Rudolf Arnheim, review of Metropolis, 1927.

Along with La Roue and The Battleship Potemkin, Metropolis (1927) is one of the great sacred monsters of the cinema. Many versions circulate, and restorations never seem to stop. A beautifully restored, though incomplete, version was premiered in Berlin in 2001. This is the basis of the most authoritative DVD releases. By now, however, everybody has heard about the 2008 discovery of a significantly longer version in Argentina, a 16mm preservation copy drawn from a scratch-infested 35 nitrate original.

Since 2008 a team at the Friedrich-Wilhelm-Murnau-Stiftung has been at work adding material from the Argentine version to the earlier one. Kristin and I have written earlier entries (here and here) tracing the progress of the restoration, and the team have produced a detailed website explaining their work. The result made its world premiere at the Berlin Film Festival earlier this year, and an exhaustive exhibition about the film has been running at the Deutsche Kinematek in Berlin.

Now I’ve seen it, at a screening during the Hong Kong International Film Festival. Frank Strobel, a member of the restoration team, conducted the Hong Kong Sinfonietta, and another collaborator, Martin Koerber, curator at the Deutsche Kinematek, was present to discuss the restoration process. A handsome booklet, cosponsored by the Goethe-Institut of Hong Kong, provided a lot of background. The film was projected digitally, but at very high resolution and looking quite crisp. I had a front-row center seat. I had a swell time.

Metropolis has never been my favorite Lang of the period, but this version makes the strongest possible case for the film. It’s hard to dislike its shameless, preposterous ambitions, its stew of biblical and modern ingredients, its bold architectural vistas, and its trancelike characterizations. Also, people running crazily about in gargantuan spaces can usually hold your interest.

I just met a girl named Maria

All [the American editors] were trying to do was to bring out the real thought that was manifestly back of the production and which the Germans had simply “muffed.” I am willing to wager that “Metropolis” as it is seen at the Rialto now is nearer Fritz Lang’s idea than the version he himself released in Germany. . . . There was originally a very beautiful statue of a woman’s head, and on the base was her name–and that name was “Hel.” Now the German word for “hell” is “hoelle” so they were quite innocent of the fact that this name would create a guffaw in an English speaking audience. So it was necessary to cut this beautiful bit out of the picture . . . .

Randolph Bartlett, The New York Times, 13 March 1927

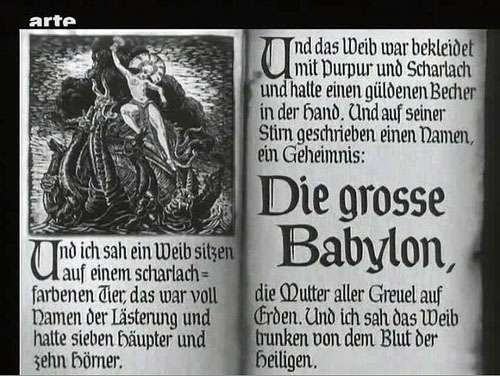

The new version gives the film a better narrative balance. Somewhat surprisingly, the plot hinges on one of the oldest and simplest narrative devices: mistaken identities. The overlord Fredersen engages the crazed scientist Rotwang to create a mechanical Maria who will lead the workers astray. Rotwang takes the occasion to avenge himself on Fredersen by having his robot urge the workers to destroy the machines. Two Marias, then–actually more, if you count the robot Maria’s incarnation as the Whore of Babylon in the Yoshiwara Club.

Thanks to the Argentine footage, we now know that another major character doubling involves Freder. At the start of the version we all know, Freder is visited by Maria and a flock of children. Upon seeing her radiant charity, he becomes suddenly convinced that he must join the oppressed workers, his “brothers and sisters.” Helping them has become his destiny. He gains an ally in Josaphat, an employee whom his father has brusquely fired. Descending to the cavernous machine halls, Freder switches identities with Georgy, a worker who returns aboveground to live Freder’s life. Freder wants him to go to Josaphat’s apartment, where they will meet. But the Thin Man, a long, leering hireling of Freder’s father, is charged with trailing Freder.

Stretches of the Thin Man subplot are missing from the previous version, but now we can see that Georgy/ Freder is a sort of early counterweight to the Maria/ Maria parallels. As in the latter case, the switch leads to misunderstanding, with the Thin Man following Georgy to the club and eventually to Josaphat. The Georgy substitution also allows Harbou and Lang to introduce the Yoshiwara Club early, but teasingly, in a rapidly dissolving montage. Only later will we get a good look at the delicious degeneracy inside.

As Martin Koerber indicated in several remarks, the older, most common version of Metropolis turns it into a science-fiction film, since it puts the robot Maria at the center of the plot. Just as important, though, is Freder’s plan for overturning class oppression, something fleshed out in the Georgy/ Josaphat material. Other new footage puts the relationship between Fredersen and Rotwang in a new light. We now see that Rotwang was in love with Fredersen’s wife Hel, and he has constructed not only a huge bust of her but also a “mechanical man,” outfitted with a distinctly female anatomy, as a sort of Hel substitute.

Fredersen diverts Rotwang’s plan to the purpose of mimicking Maria. So we get another doubling: Freder’s mother Hel becomes the firmware for the robot Maria through the machinations of two father figures. (Freder will kill one and redeem the other.) In all, the new footage yields a play of eerie Freudian substitutions.

The 2010 restoration also establishes the film as consisting of three large-scale movements. The first section, “Prelude” (Auftakt), runs a bit more than an hour. It shows Freder joining the workers and his father planning to have the Thin Man follow him. This part also introduces Rotwang, establishes Fredersen’s order to make a robot Maria, and ends with Rotwang’s capture of Maria. A second part, called “Intermezzo” and lasting about thirty minutes, is devoted to intertwining the Freder/ Josaphat plot with the creation of the robot Maria. The section more or less climaxes with a demo of the new Maria, dancing sexily at the Yoshiwara.

In “Furioso,” everything builds to a climax across a remarkable fifty minutes. The cloned Maria leads the workers to destroy the machines, fulfilling Rotwang’s plan to avenge himself on Fredersen, while the real Maria escapes from Rotwang’s compound during a fight between Rotwang and Fredersen. (We’re still lacking some of this footage.) At the same time, Freder and Josaphat converge on the underground city. The workers’ smashing of the machines triggers a flood from which the children must be saved. At the finale, during a hand-to-hand struggle with Freder, Rotwang falls to his death. There follows the famous epilogue in which Freder, “the Mediator,” must bring together hands (the foreman Grot) and head (the capitalist Fredersen).

Fluidity and freedom

This delirious fable is rendered with unrelenting zest. Lang has now perfected his breathless version of silent-film narration. He relies on simple, immediately graspable compositions, rapid crosscutting among different plotlines, and a dynamic approach to analytical editing.

In the late 1920s, many American films became more heavily dependent on intertitles; it’s as if directors were anticipating talkies. But of Metropolis’s over 1800 shots, I counted only 26 expository titles and 156 dialogue titles—in a film running nearly 2 ½ hours. Lang plunges us into each scene with no fuss, and once we’re there, a smooth continuity carries us from shot to shot. Confronting the seven deadly sins in the cathedral, Freder turns away, twisting Georgy’s cap in his hands as he exits the frame.

Cut to the main area of the cathedral, and Freder is still twisting the cap as he enters the frame. (Like other shots from the Argentine version, this is slightly reduced because of the 16mm source.)

He lifts the cap, and we get his point of view on Georgy’s name and number.

Cut to the Yoshiwara nightclub closing, as Georgy steps groggily into the street.

Here the new footage lets us see that Lang is exploiting the sort of verbal and imagistic hooks he had developed in earlier films: from Georgy’s cap to Georgy himself, with no need of an intertitle to take us to the new scene.

Lang’s freedom of camera position is typical of late silent cinema, but he deploys his angles with characteristic precision. As usual in Europe, Hollywood-style continuity isn’t completely adhered to—there are some crossings of the 180-degree line—but Lang is careful to keep us oriented to the action through eyelines. This allows great flexibility in camera placement.

Fredersen is dictating to his secretaries while Josaphat is monitoring prices. A vast establishing shot shows all of them.

Fredersen’s pacing around his office allows Lang to introduce a new area around the window and the desk.

Now pacing in the center of the office, Fredersen pauses in his dictation and Freder bursts in behind him.

But Fredersen, who’s already holding up one hand as he speaks, simply twists his wrist, and this silences his son.

The shot approximates Freder’s point of view, but Lang gets a bonus from it. The sharp change of angle makes the imperious hand (and not, say, Fredersen’s expression) the compositional focus of the shot. In fact, this sort of hovering hand will become part of the characterization of Fredersen, and Lang will stress it through, once more, energetic changes of angle.

And still later, the framing will spotlight Freder’s pointing finger by pushing it to one zone on the far right of the shot.

Lang’s concise handling of such small actions forms a delicate counterbalance to the mass movements elsewhere in the film. Perhaps for him, both gestures and crowd scenes are merely two ways of creating a geometry that can activate every area of the screen.

The carefully controlled freedom of spatial construction is facilitated by one of Lang’s favorite tactics: shooting from directly on the axis of character interaction. (No, Wes Anderson didn’t invent this.) Lang in effect sets the camera between the two characters so that they stare out at us, as if mesmerized. The technique is most memorable in the scene in which Freder is confronted by Maria and the children.

Again, though, the Argentine material brings more instances to our attention.

Putting the camera on the axis allows Lang leeway in changing his angles. From a shot on the center line, you can cut to pretty much any other area of space.

Lang’s crisp visual narration comes to a climax in the well-named Furioso section. As the action ramps up, the characters rush from spot to spot, hurling themselves into the frame and then abruptly halting to hold the composition.

The extreme case is the robot Maria, whose head and limbs jerk puppetlike from one position to another.

In all, Lang’s precise, almost diagrammatic visual style rushes us through the film’s wild plot and dazzling architecture. An emblem of precision in the service of slightly demented material might be that memorable close-up of the robot Maria: One eye staring out normally, the other half-closed, and the mouth half-twisted in a leer, as if the circuitry in the skull was failing.

A little encyclopedia

Martin Kroeber, Togichi Akira, Winnie Fu, Sam Ho, and Wong Ain-ling discuss preservation and restoration at the Hong Kong Film Archive.

In a Q & A after the screening, Martin Koerber and Frank Strobel shared information about the version. They and their colleague Anke Wilkening could publish a whole book about the restoration, but here are some highlights, drawn as well from Martin’s comments at a lengthy seminar at the Hong Kong Film Archive.

*Sources for information about the premiere version include a copy of the script (helpfully marked with reel ends and calculations about running time), censorship cards recording the credits and intertitles reel by reel, Gottfried Huppertz’s musical score, and thousands of production stills.

*Using these materials, earlier researchers were able to create a sort of mosaic of the version that premiered in Berlin in January 1927. The resulting study film embedded long swathes of blank footage as place-holders. The fact that the Argentine shots fitted in neatly proved the validity of that edition. This study film may be ordered on DVD at nominal cost by educational and research institutions.

*What’s still missing? Some shots in the Argentine version may have been censored; we’re missing a bit in which Georgy, at liberty in a cab, sees a woman baring her body. Also lacking is nearly all the fight between Rotwang and Fredersen, which enables Maria’s escape. In addition, the Argentine print lacks a scene showing a monk preaching in the cathedral, which yields some apocalyptic images.

*If the film plays fast for contemporary tastes, don’t blame the restorers. This version runs at 24 frames per second. Actually, for the 1927 premiere the film was run even faster. The score includes passages accompanying missing footage as well as over a thousand synch-points for specific onscreen action. On the basis of this evidence, it seems that the film was designed to run at about 28 frames per second. This reminds us that silent-film running speeds were far from standardized, and they sometimes exceeded the 24 fps that would be established for sound film. (For more on this matter, go here and scroll down a bit.) In addition, Frank mentioned that in theatres with orchestras, the conductor could regulate the speed of the film with a dial set into the podium.

*Why insert the cropped 16mm footage in such obvious fashion? Couldn’t the framelines be adjusted to match the surrounding 35mm material? Yes, but this slight blowup of the footage would falsify the shot scale of the original footage and not match comparable shots in the 35mm footage. Moreover, Martin pointed out that because not all the scratches and fuzziness of the 16mm material could be purged, it’s better to let these stand stand out somewhat as evidence of the vagaries of film history–like leaving some damage visible in historic buildings.

*Why is the restoration in black and white, since most silent film restorations are in color? Lang was opposed to tinting and toning, so Metropolis premiered in black and white. This caused a debate among critics, some of whom considered it a promising departure from contemporary practices of coloring scenes. The tinted versions that one can occasionally see are likely export versions colored at the request of distributors in particular markets.

*Although future screenings of the 2010 version are to be accompanied by other ensembles devising their own music, there’s a powerful case for retaining Huppertz’s original score. It reflects the filmmakers’ intentions, and its Wagnerian romanticism and modern rhythms are enjoyable simply as music. Just as important, Huppertz designed his score around leitmotifs that, as in opera, can call to mind characters who aren’t onscreen at the moment.

*Metropolis, Martin argued, is too often considered simply a late Expressionist film or an early science-fiction effort. Now we can see that it’s much more: “a compendium of everything in the air in 1927 Germany.” It brings together political ideas, debates about class society and urban life, current trends in the fine arts, acting styles, and cinematic experiments. It owes a great deal to the “monumental” films of the late 1910s, such as Joe May’s Herrin der Welt (1919), but it’s also a synthesis of what filmmaking had become since then. “It’s a little encyclopedia of 1927 cinema. . . . There’s something in it for everybody.”

To see the restoration with the stirring score, vigorously conducted by Frank, was a high point of my Hong Kong trip and indeed of my filmgoing year.

This version of Metropolis was simulcast, if that’s the right word, on 12 February by Arte during the premiere at the Berlin International Film Festival. My frames are taken from that broadcast version; hence the bug. The restoration will be screened on Turner Classic Movies in the fall, and then released on DVD in the US by Kino International.

The epigraph quotation from Arnheim comes from Film Essays and Criticism, trans. Brenda Benthien (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1997), 119. The article about the US cut of the film, which became widely seen around the world, is Randolph Bartlett, “German Film Revision Upheld as Needed Here,” New York Times (13 March 1927), X3.

Thanks to Martin Koerber for an abundance of information. For further reading, he recommends Erich Kettelhut’s memoirs on designing and filming the project, Der Schatten des Architekten (Munich: Belleville, 2009), ed. Werner Sudendorf, with many documents from sketches and photos; and the Deutschen Kinemathek exhibition catalogue, Fritz Langs Metropolis, ed. Franziska Latell and Werner Sudendorf (Munich: Belleville, 2010). You can get a sense of the tangled history of the versions of the film from Martin’s article in the latter volume, which includes a detailed account of the digital restoration. An earlier version of his piece, keyed to the 2001 version, is available as “Notes on the Proliferation of Metropolis,” in Preserve Then Show (Copenhagen: Danish Film Institute, 2002), 128-137. The Metropolis exhibition runs through 25 April.

A special thanks to Lee Tsiantis, Langian extraordinaire.