Archive for the 'Documentary film' Category

Vertov, sound technology, and 3D: Recent Blu-ray releases

The Man with a Movie Camera.

Kristin here:

Every now and then we accumulate a few new DVDs and Blu-ray discs and write up a summary of each. This entry is the first time when all the discs discussed are Blu-ray. In fact, none of these releases is available in the DVD format.

Vertov and more Vertov

Soviet director Dziga Vertov is known primarily for The Man with a Movie Camera (1929), one of the most revered silent films. It is a documentary, an experimental film, a city symphony, and a witness to Soviet society in the late 1920s, all in one. Flicker Alley has done great service to silent Soviet cinema with its Landmarks of Early Soviet Cinema and the serial Miss Mend by Boris Barnet and Fedor Ozep. Now it has brought out a Blu-ray disc of a remarkable 2014 restoration of The Man with the Movie Camera.

This version is based largely on a print struck from the original negative and left by Vertov with the Filmliga of Amsterdam, an early cine-club. It subsequently passed to the Nederlands Filmmuseum. The restoration added clips culled from other archival prints to fill in gaps in this copy, producing an edition that will be a revelation to many who are used to the scratchy, contrasty, and cropped prints that have circulated for decades.

For one thing, seeing that missing left side of the frame makes a big difference. A booklet included with the disc points out that modern versions are usually taken from sound prints of the film, which required that the left portion of the frame be reserved for the sound track. As a result, that area of the image was cropped out. This new release restores the full-frame original, and the result is dramatically different from earlier versions. Its visual quality is also impressive (see top).

with the disc points out that modern versions are usually taken from sound prints of the film, which required that the left portion of the frame be reserved for the sound track. As a result, that area of the image was cropped out. This new release restores the full-frame original, and the result is dramatically different from earlier versions. Its visual quality is also impressive (see top).

Yet Flicker Alley has been too modest in emphasizing this as a release simply of The Man with a Movie Camera. The full title of the release is “Dziga Vertov: The Man with the Movie Camera and other Newly-Restored Works.” Yet the “Other Newly-Restored Works,” featured in very small print on the cover, are hardly incidental. They include features that many researchers and cinephiles have long wished that they could view in good prints–or any prints at all.

These other works include most of Vertov’s famous features of the 1920s and early 1930s: Kino-Eye (1924), his first feature; Enthusiasm: Symphony of the Donbass (1931), his first sound feature; and Three Songs about Lenin (1934), a celebration of the tenth anniversary of the death of Lenin.

I don’t think any of these films is as important as The Man with the Movie Camera. For me, Kino-Eye is the most charming, with candid depictions of peasant festivals and the like. It was Vertov’s first opportunity to stretch his ambitions after years of work in newsreels and documentaries. It has a spontaneity that perhaps disappeared in the later features.

The disc includes an informative booklet that discusses both the films and their restorations. As an extra, there is the 1925 Kino-Pravda newsreel episode that Vertov made to commemorate the first anniversary of Lenin’s death. It incorporates rare newsreel footage of Lenin, cutting it together in ways that look like modern gifs.

The visual quality is inevitably variable, with the earlier films looking contrasty, but these are no doubt the best versions that we are likely ever to have. This Man with a Movie Camera supersedes the one from the BFI (in the UK) and from Kino (in the USA), though many will want to have the latter for its lovely score by Michael Nyman. The Flicker Alley version has a very different, but highly appropriate, score by the Alloy Orchestra.

Not all of Vertov’s early features are included. For those who want more, Edition Filmmuseum’s release of A Sixth Part of the World (1926), The Eleventh Year (1928), both with a Michael Nyman score, and one shorter film plus a documentary on Vertov, remains a necessity.

3D curiosities

Flicker Alley has also developed a specialty in releasing DVDs and Blu-rays exploring film formats. The company has paid particular attention to Cinerama (This Is Cinerama, Cinerama Holiday, South Seas Adventure, Windjammer, Seven Wonders of the World, and Search for Paradise). Now, in celebration of the centennial of 3D exhibition , it branches out into 3D with 3-D Rarities, described as “A Collection of 22  Ultra-rare and Stunningly Restored 3-D Films.” (Since we cannot reproduce 3D frame enlargements, the images below are taken from the Flicker Alley webpage just linked.)

Ultra-rare and Stunningly Restored 3-D Films.” (Since we cannot reproduce 3D frame enlargements, the images below are taken from the Flicker Alley webpage just linked.)

This BD brings together a thoroughly heterogeneous collection of short items, assembled into two programs. The first, “The Dawn of Stereoscopic Cinematography,” covers the years from 1922 to 1952, with short films made outside mainstream Hollywood. Some test footage by Edwin S. Porter and William E. Waddell shown in 1915 no longer survives, so the earliest films on the program are “Kelley’s Plasticon Pictures” (1922-23), including Thru’ the Trees, a travelogue of Washington, D. C. featuring shots of famous buildings framed primarily by foreground tree branches to create planes in depth.

The items that follow range from promotional films to animated shorts to a burlesque comedy featuring two fairly tame striptease segments and two fairly unfunny comedians. A  promotional film for Chrysler shown at the New York World’s Fair (New Dimensions, 1940) traces the assembly of a new Plymouth in great detail and with impressive animation, with the parts hopping around and sliding into place on their own.

promotional film for Chrysler shown at the New York World’s Fair (New Dimensions, 1940) traces the assembly of a new Plymouth in great detail and with impressive animation, with the parts hopping around and sliding into place on their own.

For many the highlights of this first program will be four shorts from the National Film Board of Canada, two of them by Norman McLaren. The first, Now Is the Time (1951), uses the filmmaker’s familiar drawn-on-film style (right), while the second, Around Is Around (1951), employs an oscilloscope to create more abstract patterns.

Films by two of McLaren’s colleagues are also included: O Canada (1952) by Evelyn Lambart and Twirligig (1952) by Gretta Ekman. These films are among the only ones on the whole program where objects are not thrust or thrown “out” at the audience.

The first program ends with an advertisement, Bolex Stereo (1952), a camera which supposedly was going to bring 16mm 3D home-movies into people’s living rooms. The complicated technology demonstrated shows why the idea did not catch on.

The second program, “Hollywood Enters the Third-Dimension,” consists mainly of trailers interspersed with a few shorts. The trailers include It Came from Outer Space and Miss Sadie Thompson (both 1953). One fascinating film is Rocky Marciano vs. Jersey Joe Walcott (1953), and I say this as one who has no interest in boxing. This 16-minute black-and-white film starts at the training camps of the two opponents and moves on to the match itself, in which Marciano famously knocked out Walcott in less than two minutes. The in-ring controversy over the call occupies the last part of the film, giving the whole thing a distinct dramatic shape. Multiple-camera filming and 3D add visual interest.

Stardust in Your Eyes (1953), a comedy short starring comic and impersonator Slick Slavin (aka Slaven in the credits), is said in the program notes to have been “a big hit at 3-D festivals. Judge for yourselves, but I advise keeping a finger on the next-chapter button for this one.

Few of these shorts can be said to be important classics of the 3D repertoire, but overall one gains a sense of the surprising range of films made with the process. One also learns that thrusting guns, spears, swords, and even sling-shots toward the audience, as well as throwing stones and other missiles at them, never grow old as far as the makers of these films are concerned. We have a pistol aimed at us in one of the “Kelley’s Plasticon Pictures” from 1922 (below left) and a rifle in the trailer for Hannah Lee (1953, right).

At least we now have the 3D version of Mad Max: Fury Road to recharge this particular visual trope in highly original ways.

Sound marches on

Way back in 2008, when this blog was a mere two years old, I reported on the first volume of a two-disc set of DVDs inaugurating the highly ambitious project, A Century of Sound: The History of Sound in Motion Pictures. That first volume covered the period to 1932. This one is entitled “The Sound of Movies: 1933-1975.” There was of course a lot more recorded sound in that period, and the new set stretches to four Blu-ray discs, for a total of over twelve hours of running time.

I can’t claim to have watched all those hours, but every section I sampled boasted extraordinary amounts of information. Robert Gitt, who originated the project with a 1992 lecture, again narrates. The coverage includes a huge number of rare diagrams, photographs, documents, and demo reels. In addition, many of the chapters add clips from films that contained the most innovative sound techniques of their day. The Garden of Allah, Okhlahoma!, Medium Cool, and many other titles are excerpted in superb copies.

The set as a whole is a gold mine for specialist researchers and technology buffs. The discs include long and detailed passages on such topics as push-pull recording and noise reduction, the latter a crucial challenge to the sound-recording industry for decades. Teachers who searched assiduously could find many clips suitable for classroom use.

A fair amount of the material ought to be interesting to nonspecialists too. For example, the third disc includes a history of early multi-channel and directional sound. The section on early stereophonic systems is fascinating, with its coverage of Leopold Stokowski’s participation in the two most important early films to introduce this new technology to a popular audience: 100 Men and a Girl (1937) and Fantasia (1940). We get generous clips from each. From 100 Men and a Girl, we see most of the famous scene in which an orchestra plays on different levels of Stokowski’s house and multiple channels allow sonic “close-ups” of each type of instrument over close views of that section of the orchestra:

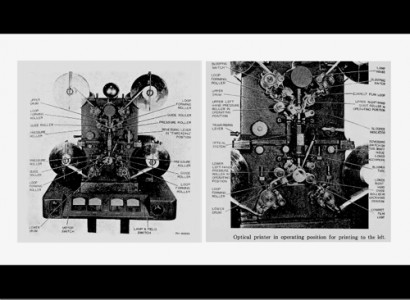

A thorough history of Fantasia includes the image below, typical of the sorts of material The Century of Sound presents: the Fantasound optical printer invented in order to print the multiple optical tracks used for the film’s stereo.

And someone obviously could not resist including a goodly dose of the short dances from the Nutcracker Suite section of the film (see bottom).

The Century of Sound is not for sale commercially. It “is available free of charge to educational, archival and research institutions and to qualified individual educators, researchers and scholars as a not-for-profit educational resource.” There is a modest fee for shipping. For information on ordering, write to CenturyofSound@cinema.ucla.edu.

Flicker Alley’s release of This Is Cinerama provoked David to a survey of Cinerama aesthetics in an earlier entry.

Fantasia.

Il Cinema Ritrovato: A final entry

The courtyard outside the Cineteca di Bologna, during Il Cinema Ritrovato.

DB here:

Some initial figures are in, and they’re fairly stupendous.

There were about 85,000 admissions to all screenings of this year’s Cinema Ritrovato, which ended ten days ago. That figure includes the big public shows on the Piazza Maggiore, but the day-in, day-out screenings were heavily attended as well. There were 2500 or so festival passes sold. Assuming that those people stayed for four of the festival’s eight days and attended four shows a day, we can surmise that at a minimum 40,000 of overall admissions came from dedicated cinephiles surging from venue to venue. And of course many passholders stayed seven or eight days and squeezed in more than four viewings on each one.

Broiling heat—one day approached 100 degrees Fahrenheit—didn’t seem to keep many away from the films, panels, book talks, and other events that crowded the schedule. Between 9 AM and 1 PM, each two-hour block offered six to eight choices, and the afternoon blocks, running from 2:30 to about 8 PM offered even more. Now that the festival has another space, a nearby university auditorium fitted for DCP projection, a whole new column of events was slotted in. Below, a bit of the queue for the Isabella Rossellini interview in the auditorium.

Next year, planners are hoping to add screenings at a renovated 100-year-old theatre on the Maggiore. There seems no doubt that the Cannes of Classic Cinema will get even bigger.

For the first time, I felt the pace was a bit rushed. Getting together with old friends was somewhat harder than before, unless you came a day or so early. (Even then, there were tempting Maggiore evening shows.) But the atmosphere was still easygoing. The courtyard of the Cineteca was an island of steamy relaxation, boasting more tables than in past years. The tent cafe provided snacks and drinks for those who simply decided not to be obsessive. Even I stopped and sat down, twice.

Word is out. A new wave of young film lovers has discovered Ritrovato. What had been dominated by hip (or hip-replaced) baby boomers was now teeming with students. The festival has added a Kids section and another devoted to older teens, and it was a pleasure to see them winding through the corridors of the Cineteca. The World Press has finally woken up too. The Guardian ran a rapturous encomium. Loyal blog sites such as Photogénie provided extensive coverage.

Just speaking for us, this was the first year Kristin and I had almost no time to blog during the event. Hence this, the last of our catch-up entries. (Click back for the earlier ones.) And I will leave out a lot.

All in favor of film, raise your hands

Has everything been said about digital cinema and its differences from photochemical cinema? Maybe so. Nonetheless, the two panels I visited on the subject raised a lot of intriguing points, in quite different formats.

The first session compared 35mm prints with digital restorations. Through clever maneuvering, the Ritrovato boffins were able to switch back and forth between versions as both were running, and the results were pretty compelling. Schawn Belston of Twentieth Century Fox provided a sample of Warlock, a twenty-year old print. It was contrasty but had saturated color; this was the sort of image I remember seeing in theatres. The digital restoration, a work in progress, was paler, with sharper edges, more solid-black shadows, and a more pastel color design. Pretty Poison was a much newer print, on Vision stock, and looked fine, as did the DCP.

Grover Crisp of Sony brought a Kubrick-approved print of Dr. Strangelove, considered best-quality in 1990s. He ran it in tandem with the recent 4K restoration managed by Cineric. The difference was very striking. For black-and-white, at least, the DCP seemed to me to have all the better of it. Kubrick, a major otaku on matters photographic, would I think have approved.

Further proof of the Crisp-Sony finesse was available in the utterly dazzling DCP we saw of Cover Girl (1944) on the big Arlecchino screen. I was surprised to find some of my circle disdaining this movie, but I think it’s wonderful. It seems to me a rough draft for many of Gene Kelly’s MGM pictures, from the trio boy-girl-stooge we get in Singin’ in the Rain (with Phil Silvers as Donald O’Connor) to the mind-bending doppelganger dance that looks forward to Anchors Aweigh and Jerry the Mouse. I also like the clever motifs of feet and faces, and the flashbacks, and …well, I must stop, because I expect to use Cover Girl as a major example in my still-unfinished book on Hollywood in the 1940s. Suffice it to say that I have never seen a better DCP rendering of Technicolor than was on display in Grover’s new edition.

Davide Pozzi rounded out the session with a pairwise comparison of different versions of Rocco and His Brothers. A vintage print from the camera negative had been vinegared, so the shots had rippling focus; the DCP restoration was fairly sharp and bright. This was a real work of reclamation.

The panelists agreed on a lot. Don’t try to banish grain; film is grainy. Don’t expect to match everything. No two prints ever looked alike anyhow, and variations among screens, lamps, and other exhibition factors don’t let us capture a pristine original experience. Because of the advances of digital restoration, there are new frustrations. Archivists are aware that older restorations may not look good today, while cinephiles who forgive scratches on “vintage” 35mm copies howl if a restoration doesn’t look smooth as silk.

Film has many futures. Pick one.

Serge Bromberg introducing the Lobster Films anniversary program, which included several “faux Lumières.”

Another panel, “The Future of Film” (let’s ban this as a title, shall we?), was less focused but more provocative. No fewer than fifteen critics, archivists, manufacturers, and filmmakers gathered before a standing-room crowd to discuss the prospects for the photochemical medium formerly known as film.

The panel’s speakers worked in shifts, three at a time. Everybody was lucid and brief. Some general points:

On the manufacturing front, Kodak and Orwo are committed to producing motion-picture stock. Christian Richter of Kodak noted that in 2006 his firm produced 11.8 billion feet of motion-picture film, while last year it produced only 450 million feet. The demand may be plateauing, but it’s too soon to be sure. The crucial problem may be the absence of labs, although boutique labs are starting to appear.

Some filmmakers, such as Gabe Klinger, consider film an essential part of their aesthetic. Alexander Payne prefers to shoot on film, but more important is film projection. He restated his view that “flicker will always be superior to glow.” By contrast, archivist Grover Crisp proposed that the standard of film projection had sunk so low that he prefers to see digital presentations, although those too can be substandard.

Some archives are preserving on film recent movies, including those shot digitally. Sony does, as does the CNC. Eric Le Roy reported that all French films receiving subsidy must deposit a print and the negative there, even if the project originated digitally. Mike Pogorzelski of the Academy archive spoke of the ongoing “Film to Film” effort, begun in 2012.

More generally, two archivists argued that the future of film lay in museums. José Manuel Costa of the Portuguese film archive argued that the basic principle had to be a respect for the nature of the medium. Cinema has changed, but it has existed in a specific technological environment since the nineteenth century, and it’s the mission of a film museum to retain that technology as long as possible. Accordingly, a film should be shown in the format in which it was made.

Belgian film archivist Nicola Mazzanti (on left above, with Pietro Marcello and Alexander Payne) seemed in accord. He remarked, in the wake of the earlier session, that digital treatment, or film restoration generally, can’t duplicate tinting, toning, stencil color, Technicolor, and other older processes. The originals are what they are—imperfect—but that imperfection is inherent in their material history. More acutely, the world outside the archive is entirely digital, so it will be a big task to keep analog alive. It will take money. And no European archive’s budget equals the cost of a single season of La Scala.

Scott Foundas, who chaired the sessions with easy good humor, indicated that perhaps the state of play was this. Digital capture and storage would not wholly replace film. By now film is recognized as distinct and worth its own attention. It’s going to exist alongside digital media for some time to come, although in niches and in more rarefied forms than before; like vinyl records.

Bologna, it became clear, is one of those places where film will continue to flourish. Fifty percent of screenings this year were analog, and the programmers included showings of Vertigo, The Heroes of Telemark, All That Heaven Allows, and other titles on “vintage” prints from earlier eras. Audiences packed in to see them and cheered.

What they saw, we must see

With all the talk of film’s enduring powers, two screenings reminded me of the power of photochemical recording as a record of history, both en masse and individual.

German Concentration Camps Factual Survey was overseen by Sidney Bernstein and involved several skilled filmmakers, including Hitchcock. It was designed to be shown to the German people as a record of what they had ignored over the last dozen years. But it remained unfinished when it was shelved in 1945.

In recent years the surviving reels have been shown occasionally under the title Memory of the Camps. In 2008 several staff at London’s Imperial War Museum began to restore the original and fill out the final reel. The filmmakers added a new recording of the original commentary, previously not attached to the footage.

Friends of Andy Warhol often commented that he used his ever-present Polaroid to keep his distance from his surroundings. You wonder if a similar strategy didn’t insulate, to some minimal degree, the American, British, and Russian cameramen who filmed the liberation of the camps. Their images show shriveled corpses covering the ground, flung into pits, shoveled into heaps. Spindly survivors move like ghostly marionettes. When I saw the first images of the bland camp officials smoking and chatting under guard, I immediately wondered: What self-control it must have taken not to have killed these men on sight.

The film is structured as a sort of anti-Grand Tour, starting in Bergen-Belsen, where SS officers seem genuinely annoyed at being forced to clear out the dead. The film moves eastward, guiding us by maps, to end in the abandoned Nazi extermination camps built in German-occupied Poland. Here shoe brushes, spectacles, and children’s toys fill warehouses. The names of German companies proudly adorn ovens.

One of the film’s main points, apparently suggested by Hitchcock, is the fact that the camps existed very close to population centers. Did the people celebrating Oktoberfest in Munich ever think of Dachau, half an hour away by train? Did the people breathing the mountain air of Ebensee spare a thought for the camp nearby? Arriving Allies insisted that people from surrounding towns be brought to witness what they had ignored. In the footage, men, women, and children file by the carnage.

Some seem moved, but eerie shots show town elders standing stiff and impassive before heaps of bodies.

Toby Haggith, one of the film’s restorers, was on hand for a follow-up session, something really demanded by the intensity of the experience. He answered questions with great seriousness and eloquence. He explained that the restoration team had decided to leave in the film’s original errors, based on contemporary reports of the size or uses of certain camps, as well as the film’s avoidance of focusing on Jewish victims. The film stresses the Nazis’ crimes against humanity at large, an emphasis, as Haggith pointed out, in tune with the United Nations initiative of the moment. “The very historicity of the film is what seizes us.”

Godard has suggested that there must be footage of the day-to-day running of the camps. Would the society that devised Agfa film and Arriflex cameras have failed to document the industrial-scale slaughter of which the Reich was so proud? Were there no amateur cineastes among the SS-men leading comfortable lives in their cottages? Was there no Leni Riefenstahl to cheerfully lend credibility to these charnel houses? Even if such footage exists, German Concentration Camps Factual Survey will serve as an unforgettable reminder that humans have a terrifying gift for brutality, and for ignoring horrors enacted right beside them.

Many doubts, much faith

Visita ou Memórias e Confissões.

In 1982, financial setbacks forced the Portuguese director Manoel de Oliveira to sell the house he had lived in for forty years. Before leaving, he decided to record his affection for the place. The result, Visita ou Memórias e Confissões was the quietest film I saw at Ritrovato. It was also one of the best.

We start at the gateway, coming in as if guests. But who owns the voices we hear? The murmuring man and woman who seem to be our surrogates passing along the path? We never see them as they enter the magnificently curvilinear house. But is it right to say they? Although we hear two voices, we hear only one person’s footsteps. The somewhat whimsical uncertainty that haunts so many Oliveira films is summoned up here by the simplest of means.

Eventually Oliveira greets us, standing in his study before his typewriter, and he explains some of the house’s history. He also runs some footage on a 16mm projector that coaxes him into discussing death, women, virginity, and sanctity. “I’m a man of many doubts and much faith.” Occasionally we hear the couple whispering as we coast past art objects and family pictures.

Oliveira tells us of his 1963 arrest while making Rite of Spring and his 1974 conflict with workers in his family’s factory—a tumultuous event that, we learn rather late, is the cause of his financial distress. These revelations come in the midst of a fascinating account of his family, accompanied by a tribute to his wife, to whom the film is dedicated. Individual history and social history blend in his recollections and the flow of visual memorabilia.

The spectral visitors glide out with us, and the film that Oliveira has been showing halts, leaving us a blaring white frame. According to his wishes, Visita wasn’t shown until after his death. Perhaps in 1982 he expected that event to come rather soon; he was seventy-three, after all.

He couldn’t have known, surely, that he would live another thirty-three years and make twenty-four more films. As José Manuel Costa pointed out, the great director wanted the film to be shown posthumously not as a final boast, but rather a wry, modest memoir of an exceptionally full life. By turns ironic and confessional, Oliveira’s testament demonstrates that we can be moved by a soft-spoken, patient peeling back of layers of the past.

Of course it was shown on film.

Kristin and I thank the many staff members who make Ritrovato such a wonderful experience. Special thanks to Gian Luca Farinelli, Guy Borlée, and Cecilia Cenciarelli. We are particularly grateful to Marcella Natale for her many moments of assistance, including giving us preliminary attendance figures.

German Concentration Camps Factual Survey will play several film festivals and public venues during the rest of the year and will eventually be distributed on DVD. Night Will Fall (2014), André Singer’s documentary on the making and restoration of the original film, is already available.

P.S. 31 July: Danny Kasman has an illuminating interview with Toby Haggith on the Factual Survey, along with important background information, at Cineaste.

Unveiling Ebertfest 2014

Kristin here:

In the early days of Ebertfest, Roger personally introduced every film at this five-day event, which took place this year from April 23 to 27. He would be onstage for the discussions and question sessions after each screening, often joined by directors, actors, or friends in the industry.

In the summer of 2006, there began the long battle with cancer that Roger fought so determinedly. He withdrew gradually from full participation in the festival that he had founded in his hometown of Champaign-Urbana sixteen years ago. He struggled to immerse himself in the festival, even though repeated surgeries had robbed him of his voice. He introduced fewer films, doing so with his computer’s artificial voice, and when even that became too taxing, he sat in his lounge chair at the back of the Virginia Theater, enjoying the event and occasionally appearing onstage with a cheery thumbs-up. Finally, last year on April 4, less than three weeks before the fifteenth Ebertfest, he passed away. That year’s festival became a celebration of his life.

The celebration continued this year, though on a more upbeat note. Some films were chosen from a list that Roger had left to his wife Chaz and festival organizer Nate Kohn, and they selected others in the same indie spirit. The tradition of showing a silent film with musical accompaniment was maintained. As always, the festival passes sold out, and the crowd, including many long-time regulars, enthusiastically cheered both films and filmmakers.

The tributes

Roger did not live to see the documentary devoted to his life and based on his popular memoir of the same name, Life Itself. It premiered in January at this year’s Sundance Film Festival. He participated in its making, however, encouraging director Steve James (whose 1994 documentary Hoop Dreams Roger had championed) to film him during the final four months of his life. Some of this candid footage reveals the painful and exhausting treatments Roger underwent, but much of it stresses his resilience and the support of Chaz and the rest of his family.

Life Itself was the opening night film. James has done a wonderful job of capturing the spirit of the book and in assembling archival footage and photographs, interspersed with new interviews. The result is anything but maudlin, with a candid treatment of Roger’s early struggles with alcoholism and an amusing summary of Roger’s prickly but affectionate relationship with his TV partner Gene Siskel.

Life Itself was picked up for theatrical distribution by Magnolia Pictures and will receive a summer release, followed by a showing on CNN. (Scott Foundas reviewed the film favorably for Variety, as did Todd McCarthy for The Hollywood Reporter.)

Another tribute followed the next day, when a life-size bronze statue of Roger by sculptor Rick Harney was unveiled outside the Virginia Theater (above). Harney portrays Roger in his most famous pose, sitting in a movie-theater seat and giving a thumbs-up gesture. There is an empty seat on either side of him, so that people can sit beside the statue and have their photos taken. (See the image of Barry C. Allen in the section “Of Paramount importance,” below.)

Far from silent

Roger was a big fan of the Alloy Orchestra, consisting of (L to R above) Terry Donahue, Ken Winokur, and Roger Miller, who specialize in accompanying silent films. They have appeared several times at Ebertfest, playing original music for such films as Metropolis and Underworld. Rather than taking a traditional approach to silent-film music, using piano, organ, or small chamber ensemble, they compose modern scores, played on electronic keyboard combined with their well-known “rack of junk” percussion section, including a variety of found objects, supplemented with musical saw, banjo, accordion, clarinet, and other instruments. The result is surprisingly unified and provides a rousingly appropriate accompaniment to the silents shown at Ebertfest over the years.

I have had the privilege of introducing the film and leading the post-film Q&A on some of these occasions, including for this year’s feature, Victor Seastrom’s 1924 classic, He Who Gets Slapped. (Swedish director Victor Sjöström used the Americanized version during his career in Hollywood.) I put the film in context by pointing out three important historical aspects of the film. First, it was the first film made from script to screen by the newly formed MGM studio, formed in 1924 from the merger of Goldwyn Productions, Metro, and Louis B. Mayer Pictures. (Two earlier releases by MGM were Norma Shearer vehicles which originated at Mayer.) Second, it was probably the film that cemented Lon Chaney’s stardom, after his breakthrough role as Quasimodo in the 1922 Hunchback of Notre Dame. Starting in 1912, Chaney had been in well over 100 films before Hunchback, many of them shorts and nearly all of them supporting roles. Third, He Who Gets Slapped was Seastrom’s second American film after Name the Man in 1923, and a distinct improvement on that first effort.

Naturally MGM wanted a big, prestigious hit for its first production, and He Who Gets Slapped came through, being both a critical and popular success–and also boosted Norma Shearer to major stardom. Seastrom and Chaney both stayed on at MGM, though the former returned to European filmmaking after the coming of sound and Chaney died in 1930.

I was joined for the post-film discussion by Michael Phillips of the Chicago Tribune, and we talked with Donahue and Winokur while Miller sold the group’s CDs and DVDs in the festival shop. They revealed that this new score had been commissioned by the Telluride Film Festival and that it was a project that appealed to their taste for off-beat films. There were many questions from the audience, and we suspect that the Alloy Orchestra will continue to be a regular feature of the festival.

A cornerstone of indie cinema

Although Roger was occasionally criticized for supposedly lowering the tone of film reviewing by participating in a television series, he and partner Gene Siskel regularly tried to promote indie and foreign films that didn’t get wide attention. Roger did the same in his written reviews, and Ebertfest was originally known as the “Overlooked Film Festival.” Inevitably it was shortened by many attendees to “Ebertfest,” and eventually that name became official. It reflects the wider range of films that came to be included, with the silent-film screening and frequent showings of 70mm prints of films like My Fair Lady that were hardly overlooked.

Among Roger’s friends was Michael Barker, co-founder and co-president of Sony Pictures Classics, one of the most important of the small number of American companies still specializing in independent and foreign releases. A long-time Ebertfest regular, Barker usually brings a current or recent release to show, along with filmmakers or actors. This year he was doubly generous, bringing Capote (2005, above), to which Roger had given a four-star review, and the current release Wadjda (2012).

Roger never reviewed the latter, but it is certainly the sort of film that he loved: a glimpse into a little-known culture by a first-time filmmaker with a progressive viewpoint. Wadjda is remarkable as the first feature film made in Saudi Arabia, where there are no movie theaters. Moreover, it was made by a woman, Haifaa Al-Monsour, and tells the story of a little girl who defies tradition by aspiring to buy and ride a bicycle in a country where this, like women driving cars, was illegal. (Below, Wadjda learns to ride a bicycle on a rooftop, hidden from public view.)

Both the film and Al-Monsour thoroughly charmed the audience. Barker interviewed her afterward, and she revealed that, not surprisingly, the making of the film was touched by the same sort of repression that it portrays. Women are not allowed to work alongside men in Saudi Arabia, so Al-Monsour had to hide in a van while shooting on location. Given that there is no cinema infrastructure in the country, the film was a Saudi Arabian-German co-production, with Arabic and German names mingling in the credits. We also learned that it has since become legal for Saudi girls to ride bicycles. Perhaps someday filmmaking will become more common there, and male and female crew members can work openly together.

Naturally Wadjda was made with a digital camera, since this new technology is crucial to the spread of filmmaking in places like the Middle East where there is little money or equipment for production. In contrast, Capote was shown in a beautiful widescreen 35mm print that looked great spread across the entire width of the Virginia’s huge screen. Naturally the screening became a tribute to the late Phillip Seymour Hoffman, giving his only Oscar-winning performance (out of four nominations) in the lead role.

Barker had brought with him a surprise guest, Capote‘s director, Bennett Miller, whose appearance had not been announced in advance. He discussed how he and scriptwriter Dan Futterman learned that there was a second, rival Capote film in the works, Infamous (2006), which also dealt with the period when the author was researching In Cold Blood. Miller and Futterman decided to press ahead, a wise move in that their film drew more attention than did Infamous. Much of the discussion was devoted to Hoffman’s performance and his acting style in general.

Capote was Miller’s first fiction feature. He had come to public attention with his documentary The Cruise (1998), which Roger had given a brief three-star review. Roger continued his support for Miller with a four-star review for Moneyball (2011). It’s a pity he did not live to see Miller’s latest, Foxcatcher, which will be playing in competition at Cannes in May.

Overlooked no longer

Perhaps no young filmmaker better demonstrates the impact that Roger’s support can have on a career than Ramin Bahrani. Roger saw his first feature, Man Push Cart, at Sundance in 2006 and invited it and the filmmaker to the  “Overlooked Film Festival” that April. (Roger’s Sundance review is here.) The film then played other festivals, notably Venice and our own Madison-based Wisconsin Film Festival. It won several awards, including an Independent Spirit Award for best first feature. In October Roger gave the film a more formal review, awarding it four stars. Man Push Cart never got a wide release, and it certainly didn’t make much money. Still, quite possibly the high profile provided by Roger’s attention allowed Bahrani to move ahead with his career.

“Overlooked Film Festival” that April. (Roger’s Sundance review is here.) The film then played other festivals, notably Venice and our own Madison-based Wisconsin Film Festival. It won several awards, including an Independent Spirit Award for best first feature. In October Roger gave the film a more formal review, awarding it four stars. Man Push Cart never got a wide release, and it certainly didn’t make much money. Still, quite possibly the high profile provided by Roger’s attention allowed Bahrani to move ahead with his career.

His second film, Chop Shop, brought him to Ebertfest a second time, in 2009. (Roger’s program notes are here, and his four-star review here.) At about that time, Bahrani’s third film, Goodbye Solo, was released. Given its modest budget, it did reasonably well at the box office, grossing nearly a million dollars worldwide (in contrast to Man Push Cart‘s roughly $56 thousand). Bahrani inched toward mainstream filmmaking with At Any Price (2012), starring Dennis Quaid and Zac Efron, and he is currently in post-production on 99 Homes, with Andrew Garfield, Michael Shannon, and Laura Dern. During the onstage discussion, he spoke of struggling to maintain a balance between the indie spirit of his earlier films and the more popularly oriented films he has recently made.

Bahrani visited Ebertfest for a third time this year, belatedly showing Goodbye Solo. We had enjoyed this film when it came out, and it holds up very well on a second viewing. It’s a simple story of opposites coming together by chance. An irrepressibly talkative, friendly immigrant cab driver, Solo (a nickname for Souléymane), becomes concerned when a dour elderly man engages him for a one-way trip to a regional park whose main feature is a windy cliff. He fears that William is planning suicide. Solo arranges to drive William whenever he calls for a cab and even becomes his roommate in a cheap hotel. Gradually, with the help of his young stepdaughter Alex, he seems to draw William out of his defensive shell.

As in Bahrani’s earlier films the main character is an immigrant and played by one, using his own first name (Souléymane Sy Savané). He’s the main character in that we are with him almost constantly, seeing William only as he does. William is a vital counterpart to him, however. He is perfectly embodied by Red West, an actor who worked for Elvis Presley and did stunt work and bit parts in films and television since the late 1950s. He may look vaguely familiar to some viewers, but he’s not really recognizable as a star and comes across convincingly as an aging man buffeted by life’s misfortunes.

Most of the film takes place in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, Bahrani’s hometown, with many moody, atmospheric shots of the cityscape at night. One crucial scene involves a drive into the woods and mountains, however, and much of it is filmed in a dense fog. One questioner from the audience asked if Bahrani had planned to shoot in such weather or if, given his short shooting schedule, the fog turned out to be a hindrance to him. He responded that he had dreamed of being able to shoot in fog and that the weather cooperated on the three days planned for that locale. In fact, he re-shot some images as the fog became denser, to keep the scene fairly consistent.

Bahrani’s presence at Ebertfest spans half its existence, from 2006 to 2014. As the festival becomes more diverse in its offerings, it is good to have him back as a reminder of the Ebertfest’s early emphasis on the “overlooked.”

Of Paramount importance

Logo for National Telefilm Associates, TV syndication arm of Republic Pictures.

DB here:

Among the guests at this year’s E-fest was Barry C. Allen. For over a decade Barry was Executive Director of Film Preservation and Archival Resources for Paramount. That meant that he had to find, protect, and preserve the film and television assets of the company—including not just the Paramount-labeled product but libraries that Paramount acquired. Most notable among the latter was the Republic Pictures collection.

We may think of Republic as primarily a B studio, but it produced several significant films in the 1940s and 1950s—The Red Pony, The Great Flammarion, Macbeth, Moonrise, and Johnny Guitar. John Wayne became the most famous Republic star in films like Dark Command, Angel and the Badman, and Sands of Iwo Jima. John Ford’s The Quiet Man was Wayne’s last for the studio, which folded in 1959. Next time you see one of the gorgeous prints or digital copies of that classic, thank Barry for his deep background work that underlies the ongoing work of his dedicated colleagues.

Barry told me quite a lot about conservation and restoration, but just as fascinating was his account of his earlier career. A lover of opera, literature, and painting since his teenage years, he was as well a passionate movie lover. An Indianapolis native, he thinks he saw his first movie in 1949 at the Vogue, now a nightclub. He projected films in his high school and explored still photography. He was impressed when a teacher told him: “If you want to make film, learn editing.” Soon he was in a local TV station editing syndicated movies.

Barry told me quite a lot about conservation and restoration, but just as fascinating was his account of his earlier career. A lover of opera, literature, and painting since his teenage years, he was as well a passionate movie lover. An Indianapolis native, he thinks he saw his first movie in 1949 at the Vogue, now a nightclub. He projected films in his high school and explored still photography. He was impressed when a teacher told him: “If you want to make film, learn editing.” Soon he was in a local TV station editing syndicated movies.

Hard as it may seem for young people today to believe, in the 1950s TV stations routinely cut the films they showed. Packages of 16mm prints circulated to local stations, and these showings were sponsored by local businesses. Commercials had to be inserted (usually eight per show), and the films had to be fitted to specific lengths.

WISH-TV ran three movies a day, and two of those would be trimmed to 90-minute air slots. That meant reducing the film, regardless of length, to 67-68 minutes. Barry’s job was to look for scenes to omit—usually the opening portions—and smoothly remove them. Fortunately for purists, the late movie, running at 11:30, was usually shown uncut, and then the station would sign off.

By coincidence I recently saw a TV print of Union Depot (Warners, 1932) that had several minutes of the opening exposition lopped off. We who have Turner Classic Movies don’t realize how lucky we are. Fortunately for film collectors, some stations, like Barry’s, retained the trims and put them back into the prints.

While working at WISH-TV, Barry began booking films part-time. He programmed some art cinemas in the Indianapolis area during the early 1970s, mixing classic fare (Marx Brothers), current cult movies (Night of the Living Dead), and arthouse releases like Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie—a bigger hit than anyone had anticipated. He also helped arrange a visit of Gloria Swanson with Queen Kelly; she carried the nitrate reels in her baggage.

At the same time, Barry was learning the new world of video editing, with ¾” tape and telecine. Because of his experience in television, Barry was contacted by Paramount to become Director of Domestic Syndication Operations. His chief duty was to deliver films to TV stations via tape, satellite, and prints. From that position, he moved to the preservation role he held until 2010, when he retired.

Barry is a true film fan. He has reread Brownlow’s The Parade’s Gone By many times and retains his love for classic cinema. The film that converted him to foreign-language cinema was, as for many of his generation, Children of Paradise, but he retains a fondness for Juliet of the Spirits, The Lady Killers, and other mainstays of the arthouse circuit of his (and my) day. He’s proudest of his work preserving John Wayne’s pre-Stagecoach films.

It was a great pleasure to hang out with Barry at Ebertfest. Talking with him reminded me that The Industry has long housed many sophisticated intellectuals and cinephiles. Not every suit is a crass bureaucrat.

Young-ish adult

Patton Oswalt had planned to come to Ebertfest in an earlier year, to accompany Big Fan and to show Kind Hearts and Coronets to an undergrad audience. He had to withdraw, but he showed up this year. On Wednesday night he screened The Taking of Pelham 123 to an enthusiastic campus crowd, and the following night, after getting his Golden Thumb, he talked about Young Adult. (Roger’s review is here.)

As you might expect from someone who has mastered stand-up, writing (the excellent Zombie Spaceship Wasteland), TV acting, and film acting, Oswalt stressed the need for young people to grab every opportunity to work. He enjoys doing stand-up; with no need to adjust to anybody else, it’s “the last fascist post in entertainment.” But he also likes working with other actors in the collaborative milieu of shooting film. He insists on not improvising: “Do all the work before you get on camera.” I was surprised at how quickly Young Adult was shot—one month, no sets. Oswalt explained that one aspect of his character in the film, a guy who customizes peculiar action figures, was based on Sillof, a hobbyist who does the same thing and sells the results. Oswalt talks about Sillof and Roger Ebert here.

As you might expect from someone who has mastered stand-up, writing (the excellent Zombie Spaceship Wasteland), TV acting, and film acting, Oswalt stressed the need for young people to grab every opportunity to work. He enjoys doing stand-up; with no need to adjust to anybody else, it’s “the last fascist post in entertainment.” But he also likes working with other actors in the collaborative milieu of shooting film. He insists on not improvising: “Do all the work before you get on camera.” I was surprised at how quickly Young Adult was shot—one month, no sets. Oswalt explained that one aspect of his character in the film, a guy who customizes peculiar action figures, was based on Sillof, a hobbyist who does the same thing and sells the results. Oswalt talks about Sillof and Roger Ebert here.

It’s common for viewers to notice that Mavis Gary, the malevolent, disturbed main character of Young Adult, doesn’t change or learn. “Anti-arc and anti-growth,” Oswalt called the movie. I found the film intriguing because structurally, it seems to be that rare romantic comedy centered on the antagonist.

Mavis returns to her home town to seduce her old boyfriend, who’s now a happy husband and father. A more conventional plot would be organized around Buddy and his family. In that version we’d share their perspective on the action and we’d see Mavis as a disruptive force menacing their happiness.

What screenwriter Diablo Cody has done, I think, is built the film around what most plots would consider the villain. So it’s not surprising that there’s no change; villains often persist in their wickedness to the point of death. Attaching our viewpoint to the traditional antagonist not only creates new comic possibilities, mostly based on Mavis’s growing desperation and her obliviousness to her social gaffes. The movie comes off as more sour and outrageous than it would if Buddy and Beth had been the center of the plot.

Making us side with the villain also allows Oswalt, as Matt Freehauf, to play a more active role as Mavis’s counselor. In a more traditional film, he’d probably be rewritten to be a friend of Buddy’s. Here he’s the wisecracking voice of sanity, reminding Mavis of her selfishness while still being enough in thrall to high-school values to find her fascinating. As in Shakespearean comedy, though, the spoiler is expelled from the green world that she threatens. It’s just that here, we go in and out of it with her and see that her illusions remain intact. Maybe we also share her sense that the good people can be fairly boring.

All you can eat

There aren’t any villains in Ann Hui’s A Simple Life, a film we first saw in Vancouver back in 2011. Roger had hoped to bring it last year, but Ann couldn’t come, as she was working on her upcoming release, The Golden Era. This year she was free to accompany the film that had a special meaning for Roger at that point in his life.

The quietness of the film is exemplary. It’s an effort to make a drama out of everyday happenings—people working, eating, sharing a home, getting sick, worrying about money, helping friends, and all the other stuff that fills most of our time. The two central characters are, as Roger’s review puts it, “two inward people” who are simple and decent. Yet Ann’s script and direction, and the playing of Deanie Yip Tak-han and Andy Lau Tak-wah, give us a full-length portrait of a relationship in which each depends on the other.

Roger Leung takes Ah-Tao, his amah, or all-purpose servant, pretty much for granted. She feeds him, watches out for his health, cleans the apartment, even packs for his business trips. When he’s not loping to and from his film shoot, he’s impassively chowing down her cooking and staring at the TV. A sudden stroke incapacitates her, and now comes the first surprise. A conventional plot would show her resisting being sent to a nursing home, but she insists on going. Having worked for Roger’s family for sixty years, Ah-Tao can’t accept being waited upon in the apartment. So she moves to a home, where most of the film takes place.

A Simple Life resists the chance to play up dramas in the facility. Thanks to a mixture of amateur actors and non-actors, the film has a documentary quality. It captures in a matter-of-fact way the grim side of the place—slack jaws, staring eyes, pervasive smells. (A small touch: Ah-Tao stuffs tissue into her nostrils when she heads to the toilet.) Mostly, however, we get a sense of the facility’s everyday routines as the seasons change. The dramas are minuscule. Occasionally the old folks snap at one another, and one visitor gets testy with her mother-in-law. One woman dies (in a bit of cinematic trickery, Ann suggests that it’s Ah-Tao), and an old man who keeps borrowing money is revealed to have a bit of a secret. It’s suggested that a pleasant young woman working at the care facility will become Roger’s new amah, but that seems not to happen. The prospect of a romance with her is evoked only to be dispelled.

Ah-Tao’s health crisis has made Roger more self-reliant, but his life has become much emptier. He seems to realize this in a late scene, when he stands in the hospital deciding how to handle Ah-Tao’s final illness. Throughout the film, food has been a multifaceted image of caring, community, friendship, childhood (Roger’s friends recall Ah-Tao cooking for them), and even the afterlife. Ah-Tao and Roger rewrite the Ecclesiastes line about what’s proper to every season by filling in favorite dishes. As he mulls over Ah-Tao’s fate, Roger is, of course, eating. But it’s cheap takeaway noodles and soda pop. This silent scene measures his, and her, loss better than any dialogue could.

The art of American agitprop

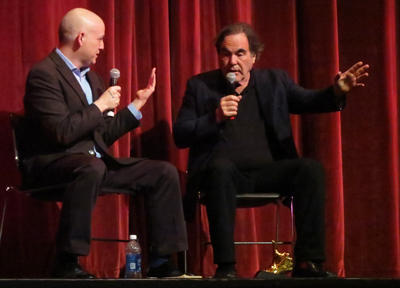

Matt Zoller Seitz and Oliver Stone on stage at the Virginia Theatre.

A Simple Life is a very quiet film. Ebertfest’s highest-profile visitors brought along two of the noisiest movies of 1989. It’s the twenty-fifth anniversary of Do The Right Thing (Roger’s review) and Born on the Fourth of July (Roger’s review), and seen in successive nights they seemed to me to put the “agitation” into agitprop.

During the Q & A, Spike Lee reminded us that some initial reviews of the film (here shown in a gorgeous 35mm print) had warned that the film could arouse racial tensions. Odie Henderson has charted the alarmist tone of many critiques. Lee insisted, as he has for years, that he was asking questions rather than positing solutions. “We wanted the audience to determine who did the right thing.” He added that the film was, at least, true to the tensions of New York at the time, which were–and still are–unresolved.

During the Q & A, Spike Lee reminded us that some initial reviews of the film (here shown in a gorgeous 35mm print) had warned that the film could arouse racial tensions. Odie Henderson has charted the alarmist tone of many critiques. Lee insisted, as he has for years, that he was asking questions rather than positing solutions. “We wanted the audience to determine who did the right thing.” He added that the film was, at least, true to the tensions of New York at the time, which were–and still are–unresolved.

The ending has become the most controversial part of the film. It’s here that Lee was, I think, especially forceful. The crowd in the street is aghast at the killing of Radio Raheem by a ferocious cop, but what really triggers the riot is Mookie’s act of smashing the pizzeria window. I’ve always taken this as Mookie finally choosing sides. He has sat the fence throughout–befriending one of Sal’s sons and quarreling with the other, supporting Sal in some moments but ragging him in others. Now he focuses the issue: Are property rights (Sal’s sovereignty over his business) more important than human life? Moreover, in a crisis, Mookie must ally himself with the people he lives with, not the Italian-Americans who drive in every day. It’s a courageous scene because it risks making viewers, especially white viewers, turn against that charming character, but I can’t imagine the action concluding any other way. Lee had to move the project to Universal from Paramount, where the suits wanted Mookie and Sal to hug at the end.

Staking so much on social allegory, the film sacrifices characterization. Characters tend to stand for social roles and attitudes rather than stand on their own as individuals. The actors’ performances, especially their line readings, keep the roles fresh, though, and the film still looks magnificent. I was struck this time by the extravagance of its visual style. In almost every scene Lee tweaks things pictorially through angles, color saturation, slow-motion, short and long lenses, and the like–extravagant noodlings that may be the filmic equivalent of street graffiti.

By the end, in order to underscore the confrontation of Radio Raheem and Sal, Lee and DP Ernest Dickerson go all out with clashing, steeply canted wide-angle shots. (We’ve seen a few before, but not so many together and usually not so close.) Having dialed things up pretty far, the movie has to go to 10.

In Born on the Fourth of July, Stone more or less starts at 11 and dials up from there. Beginning with boys playing soldier and shifting to an Independence Day parade that for scale and pomp would do justice to V-J Day, the movie announces itself as larger than life. The storyline is pretty straightforward, much simpler than that of Do The Right Thing. A keen young patriot fired up with JFK’s anti-Communist fervor plunges into the savage inferno of Viet Nam. Coming back haunted and paralyzed, Ron Kovic is still a fervent America-firster until he sees college kids pounded by cops during a demonstration. This sets him thinking, and eventually, after finding no solace in the fleshpots of Mexico, he returns to join the anti-war movement.

Even more than Lee, Stone sacrifices characterization and plot density to a larger message. The Kovic character arc suits Cruise, who built his early career on playing overconfident striplings who get whacked by reality. But again characterization is played down in favor of symbolic typicality. While there’s a suggestion that Ron Kovic joins the Marines partly to prove his manhood after losing a crucial wrestling match, the plot also insists that his hectoring mother and community pressure force him to live up to the model of patriotic young America. He becomes an emblem of every young man who went to prove his loyalty to Mom and apple pie.

Likewise, Ron’s almost-girlfriend in high school becomes a college activist and so their reunion–and her indifference to his concern for her–is subsumed to a larger political point. (The hippies forget the vets.) We learn almost nothing about the friend who also goes into service; when they reunite back home, their exchanges consist mostly of more reflections on the awfulness of the war. Later Cruise is betrayed, almost casually, by an activist who turns out to be a narc. But this man is scarcely identified, let alone given motives: he’s there to remind us that the cops planted moles among the movement.

What fills in for characterization is spectacle. I don’t mean vast action; Stone explained that he had quite a limited budget, and crowds were at a premium. Instead, what’s showcased, as in Do The Right Thing, is a dazzling cinematic technique.

Visiting the UW-Madison campus just before coming to Urbana for Ebertfest, Stone offered some filmmaking advice: “Tell it fast, tell it excitingly.” The excitement here comes from slamming whip pans, thunderous sound, various degrees of slow-motion, silhouettes, jerky cuts, Steadicam trailing, handheld shots, all jammed into the wide, wide frame. Every crack is filled with icons and noises–flags, whirring choppers, kids with toy guns, prancing blondes, commentative music. “Soldier Boy” plays on the supermarket Muzak when Ron is telling Donna about his plans.

By the time Ron visits the family of the comrade he accidentally killed, Stone finds another method of visual italicization: the split-focus diopter that creates slightly surreal depth.

Since so many scenes have consisted of a flurry of intensified techniques, simple over-the-shoulder reverse shots might let the excitement level drop. So a new optical device aims to deliver fresh impact in one of the film’s quietest moments.

Like Lee, Stone took the Virginia Theatre audience behind the scenes. He agreed with William Friedkin, who was originally slated to do the film: “This is as close as you’ll every come to Frank Capra.” Instead of using the shuffled time scheme of Kovic’s autobiography, Friedkin advised that “This is good corn. Write it straight through.” Hence the film breaks into distinct chapters, each about half an hour long and sometimes tagged with dates. They operate as blocks measuring phases of Ron’s conversion. Like many filmmakers of his period, Stone deliberately made each chapter pictorially distinct–the low-contrast Life-magazine colors of the opening parade versus the lava-like orange of the beachfront battle.

Stone pointed out that this film marked the beginning of his career as a figure of public controversy. Like Lee, he was attacked from many sides, and from then on he was a lightning rod. Matt Zoller Seitz (who’s preparing a book on Stone) pointed out that at the period, he was astonishingly prolific. From 1986 (Salvador, Platoon) to 1999 (Any Given Sunday), he directed twelve features, about one a year.

Lee was hyperactive as well over the same years, releasing fourteen films. And neither has stopped. Lee’s new film is the Kickstarter-funded Da Sweet Blood of Jesus, while Stone is touring to support the DVD release of his 2012 documentary series, The Untold History of the United States. Both men like to work, and more important, they’re driven by their ideas as well as their feelings. By seeking new ways to agitate us, they impart an inflammatory energy to everything they try. And in giving them a chance to share their insights and intelligence with audiences outside the Cannes-Berlin-Venice circuit, Ebertfest once again demonstrates its uniqueness. Roger would be proud.

The introductions and Q&A sessions for most of the films, as well as the morning panel discussions, have been posted on Ebertfest’s YouTube page. Program notes for each film are online; see this schedule and click on the title.

For historical background on Barry Allen’s work as an editor of syndicated TV prints, see Eric Hoyt’s new book Hollywood Vault: Film Libraries Before Home Video.

P. S. 1 May 2014: Thanks to Ramin S. Khanjani for pointing out that Ramin Bahrani had worked on other films before Man Push Cart. These included one feature he made in Iran, Biganegan (Strangers, 2000); it got only limited play in festivals and apparently a few theaters. I can’t find information about the others online, and presumably they were shorts and/or did not receive distribution. (K.T.)

Ann Hui, with Kristin, gets into the spirit of Ebertfest. David is represented in absentia by the Dots.

I am a camera, sometimes: TIM’S VERMEER

DB here:

Sometimes you sense that a film is made especially for you, and you expect to enjoy and admire it well before you see it. This happened, I guess, with millions of people and films like Star Wars, Twilight, and The Hunger Games. I didn’t share those viewers’ hopes, but I knew from advance publicity that I would be keenly interested in the new documentary, Tim’s Vermeer.

Why? It involves Penn & Teller, two demigods of mine; it’s about art and technology; and it investigates the possibility that a painter used optical devices to create glowing, mysterious images. In the process, it reawakens the controversy around David Hockney’s thesis in Secret Knowledge that many old masters were employing lenses and mirrors to render nature with unprecedented richness.

I wasn’t disappointed. It was the most intellectual fun I’ve had at the movies in the last year.

It’s hard to explain technical stuff clearly, and even harder to dramatize it so that audiences are engaged. Tim’s Vermeer teaches you a lot about art, technology, and human will and skill. The personality of the central figure makes the tale engrossing and funny, often suspenseful, and at moments a little wistful. At the same time you get to study one of the greatest paintings in the western world in a thoroughly unpretentious way.

There, I’ve made my recommendation. Stop now if you want your experience completely unsullied. But you’ve perhaps read other reviews, and nearly everything I mention in what follows is mentioned in at least one of those. Sony Pictures Classics has kindly put the screenplay online, so there really are no secrets if you’re determined to know it all. I want merely to convey some of the excitement the film gave me. It explores a fascinating problem in art history through one man’s patience, ingenuity, and determination.

Tim Jenison, a wealthy software innovator, is a polymath—musician, tinkerer, and fan of art. He is not a painter, but he works with images constantly; part of his fortune derives from Video Toaster and other postproduction software. He comes across as articulate, avuncular, and gifted with a self-deprecating sense of humor.

In 2001 Tim learned of two recently published books, Hockney’s Secret Knowledge: Rediscovering the Lost Techniques of the Old Masters and Vermeer’s Camera, a more academic investigation by Philip Steadman. Steadman made a strong case for Vermeer’s use of a camera obscura in painting his pictures.

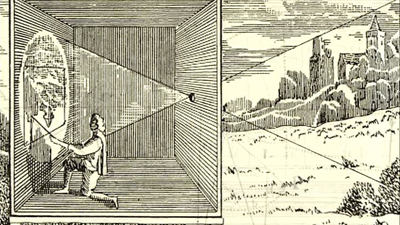

The camera obscura is a box that uses a small hole and lens to project an image of the scene outside the box. The image appears, inverted and flopped side to side, on the wall opposite the lens. Project the image onto a drawing surface, and you can trace it, although it’s difficult and requires a lot of practice.

The photographic camera is such a device, using film stock or a chip to fix the image. Amateurs used portable camera obscuras for some centuries before photography, and there’s evidence that Canaletto and other major artists employed them. A camera obscura (or “dark room”) can be any size, and it’s possible to set one up as a booth in a parlor. This is what Steadman suggested Vermeer did. Features of the paintings, such as perspective convergence and certain visual distortions, were characteristic of camera obscura images.

Hockney made bigger claims. He proposed that use of the camera obscura, along with convex mirrors and other optical gear, went far beyond Vermeer and a few other image makers. Caravaggio, for instance, seemed to him a master of staging tableaux vivants in his cellar and then copying what his array of gadgets yielded—in effect, creating a photographer’s studio.

Hockney’s proposals created a storm of controversy, with art historians, optical scientists, and cultural critics driven to fury. A common ad hominem complaint was that Hockney didn’t draw well himself and used photography to help him, so he would naturally denigrate a draftsman of genius. You can see some links to the debate in this entry’s codicil.

Steadman, a historian of architecture, used the perspective presented in the paintings to calculate the dimensions of the room and the placement of the camera obscura, and as a result he could measure the size of the projected images, which uncannily matched the size of the finished paintings. Tim took another direction.

By reflecting the camera obscura image into a hand mirror that he could position just above the picture in progress, Tim found that without training or talent he could copy a scene with astonishing accuracy. He started without a camera obscura, just using the hand mirror to paint an image from a photo of his father-in-law. The result encouraged him to go farther—much farther.

Tim’s Vermeer documents Tim’s painstaking process. He used 3D mapping to plot the space shown in The Music Lesson. He then built the room and furnished it with life-size replicas of the furniture and fittings. He ground authentic versions of the pigments and lenses used in Vermeer’s era. He even found models to stand, fixed in place by clamps, while he painted, with infinitesimal slowness, the image caught by his lens and hand mirror. By trial and error he found that adding another mirror helped even more. He was painting from a three-dimensional scene, as captured on a camera obscura.

The entire project consumed 1825 days. Documentaries always document more than they intend to, and part of the film’s attraction is its portrait of a man driven to the limit to test his hunches. His presence adds a human narrative to what could have been considered a dry academic debate. You have to wonder what Herzog would have made of this multimillionaire spending years trying to replicate a masterpiece.

Tim’s obsession yielded a remarkably exact version of the scene done entirely by hand, eye, and optical devices. The film shows Hockney and Steadman approving Tim’s picture as a valid “proof of concept,” as he calls it.

The film is carefully clear about what Tim’s demo didn’t prove. He hasn’t shown that Vermeer did it this way. We have in fact no written documents concerning how Vermeer produced his pictures, so our inferences are based wholly on the paintings and the historical circumstances. For example, Antony Van Leeuwenhoek, celebrated microscopist, lived in Delft at the same time and served as executor of Vermeer’s estate. But no documents indicate that they discussed lenses, or even knew one another.

Nor has Tim proved that he’s as good as Vermeer. Hockney insists that paintings are marks and “machines don’t make marks.” Vermeer’s touch may be inimitable and owe nothing to optics.

And Tim hasn’t supported Hockney’s suggestion that there’s no other way Vermeer could have gotten his distinctive look. Admittedly, thanks to perceptual psychologist Colin Blakemore, Tim found that Vermeer’s pictures include visual phenomena that aren’t available to our unaided eye, such as fine gradations of light on a pebbly surface. Still, perhaps Vermeer was familiar with optically generated images and imitated them, freehand, in his pictures. Perhaps he used a camera obscura simply as inspiration and a guide to visual discovery.

What Tim has shown is that a simple knowledge of how light behaves in mirrors and lenses–knowledge that was available in Vermeer’s milieu—could enable someone to produce images of extraordinary accuracy and detail, if he or she were willing to expend a hell of a lot of time and trouble.

Lawrence Gowing suggests that to Vermeer the drudgery that Tim underwent was exhilarating.

It was in the camera cabinet perhaps, behind the thick curtains, that he entered the world of ideal, undemanding relationships. There he could spend the hours watching the silent women move to and fro.

Maybe Vermeer was, as Tim suggests, an ancestor of today’s CGI geeks, toiling over his picture for days and weeks, though without the benefit of pizza and Mountain Dew. There are thousands of such people today. Were they around then too? Was Vermeer the first keyboard monkey?

The outsider’s risk

Here are some objections to the Hockney-Steadman-Jenison line of argument. I don’t think they’re insurmountable.

There are always crank theories around. But although the public discussions of Hockney’s thesis came close to calling him nuts, it’s worth listening to an artist’s conception of how another artist might work—especially when the skeptics aren’t practicing artists themselves. Hockney isn’t proposing the sort of numerological theories we get, say, in the film Room 237, or the “secret geometries” line of argument that maintains that every line and mass proves the artist was a Rosicrucian or a Freemason. Hockney’s theory may be wrong, but it’s not wacko.

Jenison is a naïve dabbler from outside the art world and lacks certified expertise. Again, it’s not a matter of who floats an idea but how valid the idea is. Why couldn’t a computer-graphics expert come up with enlightening ideas about pictures? Craftsmen in any domain often spot fine points that lay people can’t.

Besides, insiders can be mistaken. Forgers have long fooled connoisseurs. The Smiling Girl picture above was shown as a Vermeer at London’s Royal Academy in 1929, but now it’s regarded as a fake.

It’s too easy. If this were all there were to painting lifelike pictures, you might say, any kid could do it. Well, not many would have the patience. Tim spent 130 days painting the picture and he nearly gave up. It was stressful, hard on his back, and strewn with unexpected obstacles. He had to take frequent breaks. Freehand drawing is a lot easier, not to mention faster. Although Tim is no painter by training, he clearly has a careful eye and extreme fine motor control in his fingers. I, who can scarcely draw a straight line with a ruler, couldn’t do what he did.

It’s too hard. Tim’s painstaking dabbing is laborious, others might grant, but it’s donkey work. His conception of art is “difficulty of doing,” but there are lots of things that are hard to do, like building ships in a bottle, and they aren’t art. But all art requires discipline, and in those times experts labored for days over bits of the canvas that hardly anybody would notice. As a craft, painting is inherently hard, but we can scarcely imagine the amount of energy invested in the voluptuous images of Vermeer’s period. Damien Hirst can whip up high-priced paintings fast for today’s market, but conditions at that time would slow him down. He’d probably have to catch his own shark.

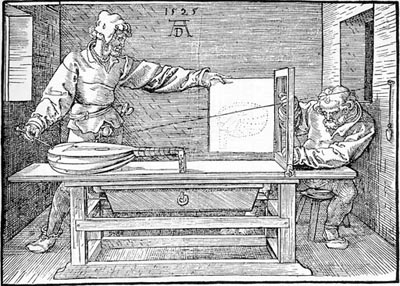

It’s too reliant on technology. But art has used mechanical devices for centuries. The best examples, very relevant to Vermeer, are all the drawing aids associated with perspective, including not just straightedges and protractors but complex gadgets like Durer’s famous converging-string setup that allowed him to draw curved volumes.

Such devices are shortcuts to deploying the geometry of the system. As Steadman says in the film, “Perspective is an algorithm.”

Later eras have given us much art dependent on technology, from tubes of oil paint to Hockney’s own Polaroid- and iPad-assisted imagery. And of course film and video art wouldn’t exist without machines. Hockney puts it well from the standpoint of the practicing painter:

[Raphael] would have wanted to make as vivid a portrait as he could. As a professional painter, he had a job to do and would have used all the tools at his disposal, including, if he thought they would help, lenses. He would not think, “I’m a great artist at the height of the Renaissance who should disdain such methods.”

Hockney and Steadman report that practicing artists they’ve encountered have been far less hostile to their ideas than art historians have been.

It insults greatness. I suppose this is what Susan Sontag meant by saying, “If David Hockney’s thesis is correct, it would be a bit like finding out that all the great lovers of history have been using Viagra.”

Actually, the copying of a camera obscura image isn’t as mechanical as one might think, but even if it were, would it be devastating? We allow photographers, with their mechanisms for intercepting light rays, the status of great artists.

The objection rests on a valid point. We do need to know something of how an artwork was made in order to understand and judge it. But in this case I don’t think that discovering that Vermeer used mechanical aids would minimize our appreciation of the pictures. It might, however, change our sense of how he relates to the traditions that followed. This change in our understanding is something Hockney and Jenison hope to bring about.

It dispells the mystery. This is the toughest argument to counter because it assumes that we want mystery in our art. It seems to me ultimately a religious way of thinking about art. I’m enough of a rationalist to hope that in any area, research can turn some mysteries into puzzles, then turn puzzles into problems, and maybe solve some of the problems.

There’ll always be a residue of questions we can’t answer. Given the feeble progress we’ve made in understanding art, no one should worry. We researchers nibble at the edges, and the Big Mysteries aren’t going away any time soon. In the meantime, we can ask whether Tim, along with Hockney, Steadman, and others, has answered some worthwhile questions about how Vermeer made his pictures.

My wish list

Here are some matters that a longer film would probably have been able to tackle. I’d love to see a version that did.

How does Vermeer fit into the broader history of art? The painting traditions in which Vermeer worked—genre scenes, portraiture, perspective–aren’t articulated in the film. In addition, the use of the camera obscura by other painters could be brought out. Perhaps the assumption is that Hockney covered that territory.

Still, to avoid certain accusations, it might have been better to grant that artists blend talent, training, and hard work with selective knowledge of what earlier artists have done, and what rivals are up to. E. H. Gombrich emphasizes the various factors involved: the tasks that artists undertake, their tools, their techniques (including inherited visual patterns, or schemas), the problems inherent in a project, and the artist’s circumstances, such as competition with other artists and the fluctuating tastes of their audience.

The exactitude of Vermeer’s interiors, for instance, is in tune with contemporary Dutch paintings of household routines (so-called genre painting) and of still-life paintings of foods glistening on a tabletop. There was a taste for meticulous presentation of everyday life at the time, and this probably impelled Vermeer toward his unique brand of realism. Was he trying to top his rivals? The film suggests that his delicacy and precision surpass what’s on display in contemporaries like Pieter de Hooch.

What counts as realism? Vermeer’s pictures look fantastically accurate, and have for some time. But he selects only certain dimensions of reality to capture. Other painters focus on movement, which is all but absent from Vermeer’s images. There’s a snapshot quality to Baroque representations of figures in action, which look scarily realistic. And many other painters render details that impress from a distance or even close up; Jan Van Eyck is probably the most famous.

What about the lenses and mirrors? Tim goes to great lengths to mimic the features of Vermeer’s room and to mix paints as he might have. The film is mostly silent, though, about his optical devices. What focal lengths were the lenses in camera obscuras? We know that different focal lengths render perspective in differing ways. Some of the distortions commentators have found in Vermeer’s picture seem to proceed from wide-angle coverage. Moreover, Tim’s hand mirror and convex mirror seem to be modern ones. Are these enough like what Vermeer would have had available?