Archive for the 'Directors: Wong Kar-wai' Category

Rights to revert to author

In the Mood for Love.

DB here:

“They never tell you that.”

My neighbor Jim Cortada is a polymath. He joined IBM in the 1970s, when history Ph.D.s faced bleak prospects for academic jobs. Since then Jim has done everything from selling mainframes to leading seminars on quality management. As a business guru, he writes books on management strategy and tactics. He also writes both popular and academic books on the history of information technology. He finds time as well to write books on his grad-school specialty, Spanish diplomatic history.

Jim’s Amazon listing consists of fifty titles. He has worked with publishers as small as Lulu and as big as Oxford. So when he talks about the nuts and bolts of publishing, I listen. His reaction to what happened to me recently is as succinct as it as accurate: They never tell you that. Put into proper context, it’s good for young academics to keep in the back of their minds.

The Syndics speak, after prodding

14 Amazons.

Early this spring, when my royalty statement from Harvard University Press arrived, I noticed an anomaly. From early 2000 through the end of 2007, Planet Hong Kong had sold about 7000 copies. The average, about 800-900 copies a year, isn’t much for trade books, but fairly solid for an academic title. Perhaps courses on Hong Kong film were using it as a text.

But the newest royalty statement brought me up short. In calendar 2008, the sales dropped off the cliff. Harvard shifted only 85 paperback copies and virtually no hardcovers.

Naturally, I blamed myself. People were losing interest, or the book wasn’t good enough to sustain an audience. But then I noticed that Amazon was offering the book only from third-party sellers. I checked Barnes & Noble and Harvard’s own website; both claimed to offer new copies. So I assumed that some long-term glitch at Amazon was leading to declining sales.

Naturally, I blamed myself. People were losing interest, or the book wasn’t good enough to sustain an audience. But then I noticed that Amazon was offering the book only from third-party sellers. I checked Barnes & Noble and Harvard’s own website; both claimed to offer new copies. So I assumed that some long-term glitch at Amazon was leading to declining sales.

So about six weeks ago I tried contacting my editor at Harvard. Getting no email replies, I left phone messages. No response.

Mossbacks among you will recognize this as a danger sign. When an editor doesn’t reply, it’s not good news. So a call to Harvard’s editorial offices brought the promise of a prompt response. An email from a good-natured staff member there gave me the lowdown: Planet Hong Kong was being taken out of print. There were too many pictures to make a reprint edition worthwhile, someone had decided. Exactly when was that decision made? That matter was left vague, but I was told that the process of transferring rights to me had already begun.

Actually, I was a little surprised at that. Transferring rights back to the author is an old-media custom, but today, when “multiple platforms” are the new business model, there’s no reason for a book to go out of print. Publishers can keep selling a book through print-on-demand or in digital copies. Why Harvard’s decision-makers chose to revert the rights to me remains a bit of a mystery.

In any event, now the 2008 sales slump made sense. Only 85 copies of PHK were sold that year because in all likelihood Harvard, having decided not to reprint, was simply exhausting its stock of copies. On the basis of past performance, those sad 85 copies probably sold fairly early in the year, so there’s reason to think that the decision not to reprint was taken at some point in 2008, perhaps quite early. Yet I wasn’t informed of the decision until I inquired in 2009.

Nor am I complaining that I wasn’t consulted about the decision. Editors and press directors never tip their hand, for the very good reason that the author has no contractual say in the matter. And telling can only cause trouble, because authors have an annoying desire to keep their books in print.

In particular, academics relish prolonged disputation. If you’re told that your book might be headed for landfill, wouldn’t you launch an ambitious plea for reconsideration, complete with references to all the people you know who love the book and reminders that generations yet unborn will be eager to absorb your ideas? (Quotes from favorable reviews optional.) If tension rises, you can always murmur about feeble marketing efforts and a risibly high cover price. It could all get nasty, and the conclusion is foregone anyhow.

So when the publisher is mulling whether to drop your book, don’t expect to have a vote. But once the press has decided to drop it, why the reluctance to tell you?

I’m the one who’s supposed to kill my darlings

Shanghai Blues.

I’ve now had six books go out of print. Correspondence with regard to two of those, back in the 1970s, is lost in the mists of time. Of the four most recent instances, I was told many months after the decision was made, and by the most impersonal of letters—not from my acquisitions editor but from somebody in the cloisters of marketing or production. In the current Planet Hong Kong case, and in an earlier instance, I learned of the book’s fate only because I inquired. Who knows when I would have been told?

Nobody likes to give bad news, and university press staff members are unlikely to be flint-hearted business people. Editors are affable and solicitous; I’ve found them good company. They work long and hard on often fruitless projects: proposals that never turn into manuscripts; manuscripts that can’t get through the vetting process; manuscripts that fall hors de combat in editorial meetings.

And academic writers are almost sadistically inconsiderate. Once professors get their book contract, they behave like their students, trotting out excuses that they laugh about in the faculty pub. They ignore deadlines, word counts, permissions—in sum, everything they signed the contract to honor. Yet these antics are tolerated with remarkably good humor. If university book editors had a taste for blood, they’d be trade book editors. Or agents.

More broadly, it seems to me, university presses are under unique pressures. The good side is that they are a business that can’t go out of business. Even in hard times like these, a university press is unlikely to be shuttered. The blow in prestige and faculty morale would be severe. So most presses limp along. Since most of their costs are bound up in salaries, wages, and benefits, the only area that can feasibly be trimmed is marketing.

Furthermore, and too few young scholars realize this, every press plays a crucial role in the tenuring process. A humanities professor teaching in most universities and many colleges typically needs to publish at least one through-written book to support a case for tenure. There is thus a vast demand that some entity publish said books. The problem is that an academic can deftly write a book that virtually no one wants to read, let alone buy. So university presses are, in effect, subsidizing the tenure process.

Seen from this angle, university publishing is a system of reciprocal altruism. The University of West Overshoe Press publishes Professor Smith’s book on cultural resistance in Girl Scout parade floats. Professor Smith is thereby on his way to tenure at his school, the University of Rising Damp. At the same time, the URD Press publishes Professor Jones’ book on sexual transgression in Futurama. Professor Jones resides at Shattered Tibia State, whose press has just accepted a manuscript (on Wittgenstein’s use of prepositions in the Tractatus) from Professor Johnson. . . who teaches at the University of West Overshoe. I’ve abbreviated the cycle, but you can see that eventually, like the spirochete in Professor Pangloss’s song in Bernstein’s Candide, everything circles around. Any one university press is supporting employment at other universities.

So I’m entirely in sympathy with university presses. And the process, eccentric though it sometimes seems, can produce good books. But presses need to deal more straightforwardly and promptly with writers when a book’s fate has been decided. Jim Cortada is right. They never tell you that. But they should, and pronto. For then you can make plans.

Planet Hong Kong 2.0

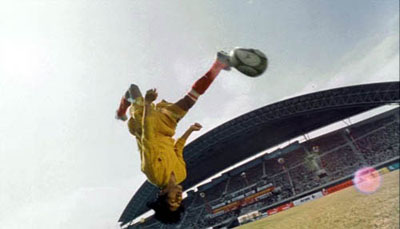

Shaolin Soccer.

The lesson for young scholars is simple. Expect that your book will go out of print. Some books will pass over to print-on-demand or digital versions, but it doesn’t hurt to expect the worst. And a book can go out of print surprisingly fast. (The original British edition of my book on Ozu lasted only about two years.) You may learn of your work’s passing by accident, as I did, or through more direct notification, but you should think about your options.

You can simply let it go, accepting the press’s rationale that your book will remain available in libraries around the world for decades. Or you can wait for Google or Amazon to get around to digitizing your work.

Yet an out-of-print book is like a child limping home after a few rough encounters with the world. You might feel duty-bound to take care of it somehow. How?

First step in salvage is to make sure pre-print materials have not been destroyed. Most contracts require that these be returned to you if you regain the rights, but publishers, speedy in so little else, can dump physical production materials in the blink of an eye. In the old days, those materials usually consisted of rolls of thick celluloid, three or four feet wide and very long, on which the pages were printed like panels on a vast comic strip. (Several of these monsters lie pod-like in my basement.) But now most books are stored on computer files, often as PDFs. Copies of those should be returned to you.

Until recently, resuscitating your book came down to trying to find another publisher. I’ve had luck with this tactic only once, with The Cinema of Eisenstein—first published by The Syndics in 1994, yanked out of print in the early 2000s, brought back by Routledge in 2005. Republishing was always rare and is now nearly nonexistent; presses can’t afford to bring out a book that may have saturated its market.

Now, though, there’s another way to revive your sickly child.

For some years I’ve argued that most “tenure books” should be published only in digital form. But university presses have been reluctant to try such an idea, since an online book might not satisfy tenure committees. The best plan would be for some well-respected university press to lock in a vetting process for online publication as rigorous as any for print books. It seems that the University of Michigan Press has begun to do this. Once the model proves its value, and once problems of piracy are solved, the practice could catch on fast. For many books I own, I’d be happy to have PDF files on my computer. There should be big cost savings and, we hope, lower purchase prices—maybe even through selling separate chapters. Like music CDs, many books have only a few chapters you want. We can look forward to the iTune-izing of academic writing.

Yet if university presses need to be cautious about online publishing, the individual scholar doesn’t. The tactic is simple: Plan to put your out-of-print books on the Web.

Some authors may prefer to take existing PDF files or make new ones from the book’s pages, and add a fresh introduction. That’s essentially what Marcus Nornes and his colleagues helped me do with Ozu and the Poetics of Cinema. We also tipped in new color images.

The alternative is to revise your book and post a second edition online. It’s a lot of work, but then you could probably charge something for it.

As for Planet Hong Kong, I’m still mulling my next step. Perhaps a publisher will be interested in a new edition, revised, corrected, and updated. Alternatively, I might prepare Planet Hong Kong for downloading on this site. Unlike the original, it could have color illustrations. I have to say that I find this option intriguing.

If you want a used copy of the old edition of PHK, about a dozen are available here. Once dealers learn it’s out of print, they may raise their prices. In any event, I hope to bring the book back in some form. Don’t say I didn’t tell you.

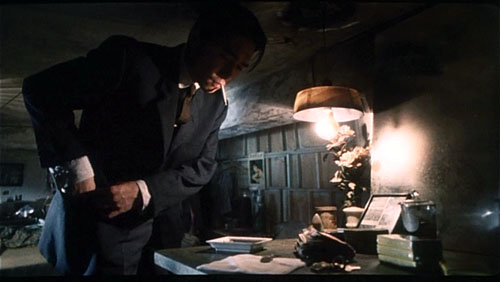

PTU.

Ashes to Ashes (Redux)

DB here:

Hong Kong films constantly shift their shapes. Both film prints and video versions circulate in a bewildering variety of forms. A movie shot in Cantonese (the vernacular of the locals) may be dubbed into Mandarin, the language of the Mainland and of Taiwan. But it may also be dubbed into English, French, or other Western languages; such was the fate of many kung-fu films of the 1970s, as well as later productions like The Killer (1989). I have seen Happy Together in Italian and In the Mood for Love in Spanish. When a movie is exported, it may also be recut to suit the local market. Typically Hong Kong producers have sold films under terms that allowed foreign distributors to do pretty much what they liked with both theatrical and video releases.

Alternatively, the filmmaker may cooperate and remake the film to fit foreign tastes. During the boom years of the 1980s and early 1990s, when many films were funded through presales to Taiwan, it was common to have both a Taiwanese version (usually longer) and a Hong Kong one. Jackie Chan’s Police Story (1985) included extra scenes of Jackie’s antics to satisfy Japanese audiences, and the directors of Infernal Affairs (2002) provided a less desolate ending to satisfy Chinese censors. In addition, filmmakers began circulating “international versions” that would play film festivals, and these might not accord with what was released locally. I’ve discussed one instance earlier on this blog: a version of Days of Being Wild that includes opening material not visible in the international print. My current supposition is that this is a local release print that may have circulated in Western Chinatowns too.

To complicate things further there was the institution of the midnight show. Instead of holding test screenings, Hong Kong producers would preview their films at a few theatres late on weekend nights. Audiences knew that they were acting as guinea pigs and weren’t shy about expressing their displeasure. While filmmakers cringed in the back, viewers might shout insults at the screen. The producers and the director would meet to settle on what changes should be made. Then they would hustle to prepare new versions for the official release in the next week or two.

On top of this, add the next layer of revision: the post-festival rethink. Western directors have redone their movies after discouraging festival response. Probably the most famous instance is the death and resurrection of Vincent Gallo’s The Brown Bunny (2003).Now that Hong Kong and Taiwanese directors circulate on the fest scene, they too have tinkered with their work after premieres, notably Hou Hsiao-hsien, who has reworked films following less than enthusiastic Cannes screenings.

A director’s job is never done?

Like many Hong Kong movies, nearly every one of Wong Kar-wai’s films went through multiple versions. But unlike many directors he seems to enjoy tweaking and rethinking his work. In production he shoots scenes, watches them, reshoots them, recuts them, and reshoots again. Editing and mixing involve the same play with variants. He adds different shots, juggles the order, adds or subtracts music at will.

The process may seem to betray an uncertainty about what he wants his movie to be. For In the Mood for Love, he shot scenes of the central couple making love but didn’t use them, playing with the possibility that the affair is chaste. 2046 began as a high-concept project, based on the fifty-year expiration of the 1997 handover accords, and it went through many different incarnations. At one point it was to be a tale of the intertwining lives of different Hong Kong citizens whose addresses were 2046 on their streets. Even the actors may not know what’s up. At the Cannes premiere of 2046, Maggie Cheung was startled to learn that she was barely in the movie.

Of course most filmmakers rediscover their films at each stage of production, but for Wong the idea of a “locked” version is fairly indeterminate. Virtually everyone now acknowledges that a Wong festival premiere is a first approximation. Delivered in the nick of time (sometimes embarrassingly late), the film is likely to be reworked after initial screenings. Venice and Cannes, Tony Rayns points out, have served as counterparts to the local midnight shows.

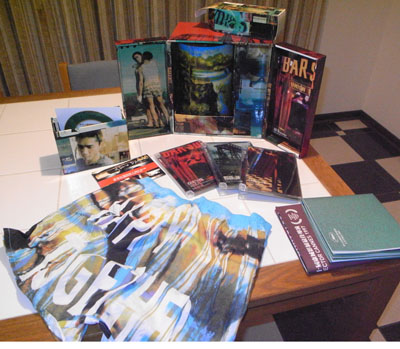

In Planet Hong Kong I suggested that Wong became a shrewd guardian of his brand. He has created high-end ancillary products, not only CD soundtracks but posters, T-shirts, glossy photo books, and limited-edition DVD sets. The Happy Together anniversary box (limited to 2046 units) includes a model of the spinning Iguazu Falls lamp and a pair of men’s briefs. The spinoffs are issued with fancy packaging, and they have usually sold briskly in upscale Asian shops, particularly in Japan. It’s characteristic that Wong’s aborted project Summer in Beijing could serve as a corporate travel logo. At once cult filmmaker and luxury franchise, Wong has every reason to refresh, and re-market, his content at intervals.

In Planet Hong Kong I suggested that Wong became a shrewd guardian of his brand. He has created high-end ancillary products, not only CD soundtracks but posters, T-shirts, glossy photo books, and limited-edition DVD sets. The Happy Together anniversary box (limited to 2046 units) includes a model of the spinning Iguazu Falls lamp and a pair of men’s briefs. The spinoffs are issued with fancy packaging, and they have usually sold briskly in upscale Asian shops, particularly in Japan. It’s characteristic that Wong’s aborted project Summer in Beijing could serve as a corporate travel logo. At once cult filmmaker and luxury franchise, Wong has every reason to refresh, and re-market, his content at intervals.

Yet I don’t maintain that he’s insincere. His drive to redo his films seems to go beyond indecision or commercial calculation. Wong seems to have taken to heart his central theme of the transient moment, the fact that love can be extinguished at any instant. So why not change your films to match your mood today? Further, like Warhol, he seems to enjoy prodigality for its own sake. He enjoys conjuring up one variation after another, multiplying just barely different avatars, and draping in mist the notion of any original text. His films’ basic constructive principle—the constant repetitions that create parallels and slight differences, loops of vaguely familiar images and sounds and situations—gets enacted in his very mode of production.

So he rebuilds even after release. The DVD release lets him tack on unused materials, extra scenes and different endings. That’s enough for most directors, but Wong has long harbored the dream of compiling vast swatches of unused footage in a sort of variorum DVD set of all his films. But why should he have all the fun? He once announced plans to put his footage for Happy Together on the Internet and let anyone make a personal version of it. That didn’t happen, but he did allow his assistants to make Buenos Aires Zero Degree (1999): not only an essayistic making-of but also a handsome reliquary of discarded material, including a gorgeous sequence of two taxis arcing away from each other.

Evil East, Malicious West, and their posse

Now we have Ashes of Time Redux, premiered at Cannes and showing in the US. The most apparent analogies, the oft-revised Blade Runner and the other redux, Apocalypse Now, don’t do justice to Wong’s fussbudget impulses.

For the original Ashes Wong assembled a high-wattage cast that included two of the Heavenly Kings of Cantopop and three glamorous female stars. He spreads out their duties by means of an ensemble plot. At the center stands Ouyang Feng (Leslie Cheung Kwok-wing), a swordsman who has set up a way station on the edge of the desert. He acts as a broker for people who want to hire killers. Another swordsman, Huang Yaoshi (Tony Leung Kar-fai) visits him every year. Ouyang nurses unrequited love for his brother’s wife (usually known as the Woman, played by Maggie Cheung Man-yuk), who lives far away. Huang is also subject to the Woman’s charms, but he is more deeply in love with Peach Blossom (Carina Lau Kar-ling), a woman he saw bathing her horse in a river. Peach Blossom is the wife of yet another wandering swordsman, who is gradually growing blind (Tony Leung Chiu-wai). He too fetches up at Ouyang’s outpost. Huang also runs afoul of the Murongs, a brother and sister who may be the same person (Brigitte Lin Ching-hsia). Meanwhile, a young girl (Charlie Yeung Choi-nei), fortified only with a mule and a basket of eggs, waits at Ouyang’s cabin to hire someone to avenge her brother’s death. Finally, there is Hong Qi (Jacky Cheung Hok-lau), a down-at-heel young killer for hire, who is followed across the desert by his wife.

The interlocking love triangles around a narcissistic man recall Wong’s breakthrough film, Days of Being Wild (1990), although here the parallels and connections are fleshed out through kinship too. The basic relations are at first hard to parse, though a Western viewer who didn’t recognize these stars will have more trouble than a Chinese one. Wong complicates the exposition by fragmenting his scenes and inserting flashbacks, though most of the latter are easy to follow.

He also helps the audience by following a common Hong Kong storytelling principle: reel-by-reel plotting. This breaks the movie into fairly discrete chunks of ten minutes (about a reel) or twenty minutes (about two reels). The first reel sets up the central relation of Ouyang Feng and Huang Yaoshi. Then two reels are devoted to the Murongs and their efforts to trap Huang. The next two reels are spent on the Blind Swordsman, followed by two reels devoted to Hong Qi and the Egg Girl. The last two reels unearth the long-simmering relationship among Ouyang, the Woman, and the despairing Huang. So the plot is actually a bit tidier than it seems at first, although each of these chunks is marbeled with references to other story lines. In Redux, Wong has also divided the plot into seasons, a strategy that accentuates the multipart structure.

Now about all those versions. Preliminary confession: These comments are based on one 35mm screening, and my analytical points are based on a DVD screener.

Keeping it unreal

Before Redux, there were at least two versions of Ashes of Time. One premiered at the Venice festival of 1994, the other became the international standard version. The differences are striking.

The international version has several hyperactive swordfights quite early. In a prologue before the title credit, Ouyang Feng and Huang Yaoshi fight a duel. After that, each is given a combat sequence in which he takes on hordes of assailants. These sequences are rapidly cut, with exaggerated angles, accelerated or slowed motion, and pulsing freeze frames. At the end of the international version comes a brief, parallel epilogue showing the surviving warriors (Ouyang, Huang, Hong Qi, and Murong) in the midst of combat. This epilogue includes a tableau of Yin, the female Murong, writhing ecstatically on a bed of red blossoms.

It’s widely believed among Hong Kong film people that this international version was initially created for the regional market and overseas Chinatowns. Wong added swordplay sequences at the beginning and end in order to satisfy his Taiwanese producers, who wanted more action in this otherwise talky and moody movie. How this version, running about ninety-five minutes without credits, became the standard one I don’t know, but evidently Wong did not control the international rights on the film. In any case, we have the evidence of Derek Elley’s Variety review that these passages were not in the Venice copy.

I’ve seen Ashes in 35mm in several countries, and it’s always been the international version. That is the version available on Hong Kong laserdisc and video, as well as on Japanese DVD (as near as I can tell from my imperfect disc). But the French DVD, released by TF1, is quite different. It runs 87:30 without credits (and assuming 24 fps). This version lacks several scenes, including the opening brawls, and ends with a close-up of the pale face of the Woman looking out to sea. It may be that this French version, billed on the packaging as the “original” one, is close to the Venice print.

Wong reports that he rescued original material, both positive and negative, from various sources. Since some of it was in poor condition, digital versions were made. In the final result, a few shots have been replaced with alternate takes. Yet the film is not simply restored but “reimagined,” as the title Redux indicates.

By and large, the sequence of story events, the shot-by-shot progression, and the monologues and dialogues are the same in both the international version and this new one. What, then, has Wong changed? He has kept nearly all of the brief prologue showing a rapid-fire combat between Ouyang and Huang. He has eliminated the approximately three minutes of the two fights that establish the solo prowess of the fighters. He has also cut the epilogue’s burst of action, retaining only a shot of Ouyang slashing in slow-motion and swiveling in a freeze frame that gradually fades out. In other fight scenes, he has trimmed some elaborate action and at least one gory bit, showing Murong impaling a cat.

Which is to say that he has deleted several conventional displays of the wuxia pian, or “heroic chivalry” film, of the 1990s. In Planet Hong Kong, I argued that Wong’s films often play off the mainstream conventions of his moment. He embraces pop music, pop stars, and pop genres: the triad movie (As Tears Go By, 1988), the melodrama (Days of Being Wild, Happy Together), and the romantic comedy/ cop movie (Chungking Express). But the films rework those conventions too. Wong subtracts a bit of glossiness by emphasizing the grubbiness of location shooting and by mussing up his stars, but then he re-beautifies things through his lustrous images and his unashamed interest in romantic longing. His men alternate between impulsive action and moody withdrawal, and his women mostly lounge about waiting for their men to make a move. (You could do a whole essay on the figure of the Waiting Woman in his work.) The sheer conviction of his style and sentiment can redeem quite hoary clichés, such as the woman’s inevitable complaint that her man never told her he loved her (a crucial turning point in Ashes of Time).

By the early 1990s, the wuxia pian had become a fantasy extravaganza, packed with flying swordsmen, magic potions, special effects, dynamic visuals, pounding music, and play with gender identity. The second and third installments of Tsui Hark’s Swordsman trilogy, a phantasmagoric treatment of the genre, present Brigitte Lin as the bi-gendered Invincible Asia, a vessel of both martial and erotic fantasies.

In part Ashes cites these current formulas in order to rework them. Conventional props like magic wine become tied to themes of memory and regret for missed chances. Discussions of combat strategy are replaced by monologues musing on lost loves. The male/ female masquerade of The East Is Red becomes, in Ashes, a hallucinatory shift of identity (are the Murongs two people or one person?) and forms one point of a thematic continuum centering on men’s desire to possess other men’s women.

Visually as well, Wong borrows and reworks fantasy wuxia conventions. One of the women warriors in The East Is Red (1993) unleashes her volcanic sword skills while standing on the surface of the sea.

Something quite similar happens in Ashes. But once Wong has turned Murong’s ambidextrous gender into a question of identity, you could argue that the geysers of water she unleashes make a broad thematic point: the primal force of a character named both Yin and Yang.

So the original Ashes reworks motifs to be found in Tsui’s extravaganzas, and for all I know in others as well. But apart from the Murong waterworks, these moments of dialogue with the fantasy wuxia pian entries are muffled in Redux.

From the original action scenes Wong has trimmed the turbocharged leaps and swoops, the blasts of “palm power,” and the possibility that a slashing blade can make a hillside explode. Perhaps Wong wanted to leave behind the overwrought world of wuxia fantasy—popular in 1994 but likely to seem cartoonish to Western audiences now. I wonder, though, why he has retained the opening clash between Ouyang and Huang, since the rest of the film presents them as friends. The answer may lie in the original Louis Cha novel, The Eagle-Shooting Heroes, a multi-volume saga that inspired both Ashes and the 1993 Jeff Lau film (co-produced by Wong) called by the novel’s title.

Other changes serve to create greater nuance or lyricism. The synthesizer score has been replaced by a spacious orchestral one, enhanced by stereo. Other stretches of music have been dropped altogether. There is a little less of the Morricone flavor now; the music coaxes rather than hammers. We get more shots of the moon, some fresh landscape vistas, a few more pools of water. Sometimes blood splashes out at us, but at one point an out-of-focus spray of blood is replaced by an optical effect showing wafting dark red billows.

The most pervasive change has involved the color tonalities. The 35mm prints of Ashes I’ve seen have favored a vivid orange-brown palette, with strong blues (sky and water), red accents, and very little green. The video copies vary, but the most commonly available DVD version is notably more russet and lower contrast than the 35mm. Redux, though, is a total rethink. Interiors have lost most of their hard-edged chiaroscuro and become softer and paler. Exteriors, and some interiors, have been keyed toward a hard yellow. The vivid browns and oranges have gone a bit gray, and the blacks verge on green. In addition, some highlights have burned out.

Consider these three frames. The first is a scanned Fujichrome slide that was photographed from a 35mm print. The second frame is from the Hong Kong DVD release. The third is from the Redux screener DVD. None has been photographically adjusted for reproduction here.

All of these are some distance from their sources; for instance, the 35mm slide can’t really capture the range of tonalities of the original, especially in the dark areas. Still, I think the relationship is a fair reflection of the differences. In 35mm, Redux looks a lot more crisp, rich, and detailed than in this DVD frame-grab, but the lemon yellows and pale greens are fairly faithful to my memory of the print.

Wong has taken advantage of ways to improve the film. Seeing the international version in 35mm, I was struck by problems in color matching. Shots apparently taken on different days didn’t always cut smoothly together, and sometimes shot/ reverse-shot passages displayed varying color grades and levels of graininess. By adding fairly consistent tints and by softening certain sequences, Wong has given the film greater tonal consistency. Further, he has upped the artificiality of the film’s look, creating a neutral ground against which certain colors, such as the wan face and ruby lips of the Woman, stand out even more vividly. With its softening and tinting, the film now looks more like a recent release–portions of Soderbergh’s Traffic, say, or some of the tamer stretches of a Tony Scott movie.

Once Redux appears on DVD, admirers will be kept busy plotting some minute differences in shot order and alternate takes. They will marvel at the way that Wong has inserted a few more images (e.g., during the fantasy caressing of Ouyang) but has kept the overall sequence the same length. There will also be intriguing questions. Why the choice of yellow as a key tone? Why the occasional and blatantly video-derived image, such as the pan shots that enframe the central story, and perversely run the opposite direction of their counterparts in the other versions? And why the digitized banks and foliage—maybe just because they look wonderful?

In case you wonder, this frame is not inverted.

I’m still getting accustomed to the film’s new look, and I need to see a print again to verify these general impressions. Still, I like to think that by recasting his film so markedly, Wong has brought his masterpiece back under his control. In this sense, his changes remind me of Stravinsky’s reorchestration of Petrushka and other early ballets. Stravinsky rewrote the scores in order to win performance rights, but he also brought his latest thinking to the task. In the same way, Wong has made Ashes of Time new all over again—available to many more viewers now and hereafter. This daring, fourteen-year-old exercise in avant-pop moviemaking is miles ahead of nearly everything on view right now.

For more on Wong Kar-wai product lines, go here. Wong talks about the restoration of Ashes here and here and in a video interview at the New York Film Festival. For more on reel-by-reel plotting in Hong Kong film, and a broader discussion of Wong’s films, see my Planet Hong Kong: Popular Cinema and the Art of Entertainment, 180-182, 271-281. For other critical discussions of Ashes of Time, see Stephen Teo, Wong Kar-wai (London: British Film Institute, 2005) and Peter Brunette, Wong Kar-wai (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2005). Unless otherwise noted, the frame enlargements in this entry are taken from a 35mm print of the 1994 international version of Ashes.

Thanks to Michael Barker of Sony Pictures Classics and Sarah Simonds and Jacob Rust of Sundance 608, Madison, Wisconsin, where Ashes of Time Redux is scheduled to open on 30 January.

Top: WKW and the Hong Kong Film Critics Society, which awarded its Best Film honor to Ashes of Time, spring 1995. Below: DB presents WKW with the award.

Fast forward, now pause

DB here:

Since Kristin got back from Petra (glimpses of her trip are here), we’ve been busy checking the page proofs of the third edition of Film History: An Introduction. It’s due out in February and we have to go over the whole enormous thing, since we’ve made adjustments to almost every chapter. There will be updates of several chapters, as well as two new chapters taking into account developments since our last edition (written in the fall of 2001). We’re also expanding our Notes and Queries supplements, which will appear online. Already our new introduction, discussing some approaches to historical research, is available elsewhere on this site.

This task hasn’t given us much time for blogging. Now, though, we are in a small hiatus before the final push, so each of us hopes to finish a blog entry this week. Kristin will write about a recent visit to Madison of Stefan Droessler, head of the Munich Film Archive. He gave lectures and screened a reconstructed Lubitsch film, The Wife of the Pharaoh (1922). My entry will focus on Wong Kar-wai’s Ashes of Time Redux. I hope to point out some interesting differences among the versions of this remarkable movie.

But to keep your eyes warm, three quick items of note.

I probably don’t have to urge you to see the new Criterion edition of Chungking Express, out in both standard and Blu-ray editions. It’s the Miramax/ Rolling Thunder version, in a crisp transfer with a nice range of color and detail. (I don’t have Blu-ray and so can’t report on that disc.) There’s also a precious 1996 British TV episode in which WKW and a beer-guzzling Chris Doyle tour some Hong Kong locales we see in the movie, tossing out technical information along the way. The show also supplies a more or less documentary record of the Midnight Express fast-food counter a couple of years after the film. Still later, the success of Wong’s film led the owner to upgrade it, with results you can see at the end of this entry.

In the supplementary short, Chris Doyle catches himself talking like a critic and says it’s because “I’ve been reading Tony Rayns.” Not by chance, the Criterion set includes a superb commentary track by Tony, who has worked closely with Wong and Doyle for years. Tony’s fluent discussion anticipates practically every question you might ask about the movie, including why Faye Wong wears a United Airlines uniform.

Chungking Express is my favorite of Wong’s work, but that’s not the main reason I devoted a chapter to it in Planet Hong Kong. I think it’s an important film historically. In the context of Hong Kong cinema, it was as much a breakthrough as was Days of Being Wild, but its offhandedness made it seem more innocuous. Wong makes daring use of plot structure: two stories, barely linked, that connect thematically rather than causally. (We also examine this aspect in one section of Film Art.) Further, Chungking Express is an exhilarating instance of a type of storytelling that fascinates me, what I call “network narrative” and that I analyze in one essay in Poetics of Cinema. Finally, because this film was more widely seen than Wong’s earlier work, it identified him with a particular style: dazzlingly composed shots alternating with smeared and rushed ones, pulsations of saturated color, precise matching of image to music, and a tone of wistful romanticism. Who else could make such an engaging movie about two guys whose girlfriends have left them?

Across his career, Wong’s technique has been more varied than the flash-and-grab breeziness of Chungking Express, Fallen Angels, and Happy Together suggests. The blurred imagery and stuttering slow motion proved easy to mimic and even parody (in Wong Jing’s Whatever You Want, 1994). In the Mood for Love and 2046 returned to the more precise and controlled staging, the nearly abstract use of setting, and the tight close-ups of Wong’s earliest films. For all their virtues, though, these late movies lack the sheer ingratiating zest of Chungking Express. If My Blueberry Nights disappointed you (as it did me), revisit the original and watch it jump off the screen. Keep an eye peeled for those reflections.

Speaking of new DVDs, today the UPS man lugged a Fox Murnau/ Borzage box to our door. This cost more than my first car (and weighs about the same), but it’s a better bargain. My oil-leaking ‘62 Impala did not come fully loaded with Sunrise and City Girl and Seventh Heaven. Dedicated Fox archivist Schawn Belston has labored hard to create this remarkable collection, as robust a contribution to our understanding of film history as his Ford at Fox box a year ago. Tucked inside the chocolate-colored case are twelve films and two handsome books with texts by Janet Bergstrom. An entire book is devoted to the lost Four Devils, and one disc houses a lengthy documentary on the two directors.

Many of the early thirties Borzages are new to me, and I can’t wait to see them. But Kristin and I are very happy to have two lesser-known titles that we love, Lucky Star (1929) and Lazybones (1925). The latter is a striking example of the trend toward the “soft style” of cinematography that swept Hollywood in the 1920s (and that Kristin analyzes in The Classical Hollywood Cinema). Even men were shot with filters, gauzes, and selective focus, creating lyrical images like the one of our hero above. The soft style was about as popular then as the dark, earth-and-steel tonalities we find in so many films today. When our travails with Film History are ended, we look forward to digging into this new Fox treasure chest.

Finally, why not try to identify a mystery movie like the one above? In an email Joe Lindner, archivist at the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, writes:

The Nitrate Film Interest Group of the Association of Moving Image Archivists has put together a page on flickr where archivists can post images of unidentified films. The submissions have tended towards silent films and nitrate prints, but sound films and safety elements are welcome as well. The page is also set up for short video clips, and the first video post has just been uploaded from a new scan of a 28mm print in the Academy Film Archive’s collection. This is also a good resource for anyone out there seeking help in identifying film elements, and you do not have to be a member of AMIA to submit images.

This is a remarkable site, and the images are tantalizing. As of this writing, several films have already been identified.

So, three snacks to tide us all over. Check in later this week for some new stuff, when our eyes will focus again.

Years of being obscure

DB here:

The Cannes screening of Ashes of Time Redux reminds us that Wong Kar-wai has been an incessant reviser of his work. Versions proliferate in different markets—one for Hong Kong, one for Taiwan, one for the international market—and he has sometimes promised online versions, or bonus DVD features. Buenos Aires Zero Degree (1999) by Kwan Pung-leung, provides tantalizing bits of scenes between Tony Leung Chiu-wai and Shirley Kwan. Yet it makes us wonder about the film we might have had if Wong had not decided to cut the whole plot strand out (after keeping Shirley in Argentina for several weeks).

We can add to the list Days of Being Wild (1990), Wong’s breakthrough movie. It’s been circulated for years in an international version, which is currently available on DVD. But some people people have recalled seeing a fugitive, somewhat hallucinatory cut of the film. Some time ago I examined that alternative, and I figured it’s worth showing what I saw. This rareversion prefigures some aspects of Wong’s later style, particularly as seen in In the Mood for Love (2000). I don’t have solutions to all the puzzles it poses, but I’ve gathered some information. If you know something about this “obscure” version, feel free to write to me and I’ll append your comments to this entry.

I need hardly add that there are spoilers galore here. In the images, differences in tonality and aspect ratio spring from my two sources, DVD and 35mm film (which itself fluctuates a little in aspect ratio from shot to shot).

Last things first

Days of Being Wild begins in 1960 Hong Kong. It follows the wanderings of Yuddy (Leslie Cheung), a preening young man who casually seduces women, notably the brassy Lulu (Carina Lau) and the subdued, naïve Lai-chen (Maggie Cheung). Living with his aunt, Yuddy wonders why his mother abandoned him. He finds her living in the Philippines but doesn’t confront her.

At the climax in Manila, Yuddy meets a sailor (Andy Lau) and picks a fight with local thugs. The two men flee by hopping aboard a train. By chance, the sailor was formerly a Hong Kong cop, who was attracted to Lai-chen. On the train, Yuddy is shot by a vengeful thug. The film concludes with a series of shots of Lulu, Lai-chen, and—the big mystery—a slick young man in a seedy apartment who files his nails, combs his hair, equips himself with handkerchief and cigarettes, and sets out for a night on the town. He doesn’t speak, and he has never appeared in the film before. It’s one of the boldest narrative maneuvers in contemporary cinema, and it has occasioned a lot of comment.

The differences in the final sequences begin on the train. In the international version, a shot of the landscape seen from between the cars is followed by a high-angle medium shot of the cop.

This constitutes a mini-flashback, since Yuddy has already died from the gunshot. The cop’s voice-over initiates the exchange: “The last time I saw him, I asked him a question.” (As usual in Wong’s work, we have no way of knowing whom is being addressed; this could be an inner monologue, a report to an unseen character, or simply a self-conscious address to the audience.) For a little more than two minutes, the camera shows only the cop. He asks if Yuddy remembers what he was doing at a certain time. Yuddy understands immediately that the cop has met Lai-chen, and he replies from offscreen, asking about the cop’s relation to her and asking him to tell her that he, Yuddy, has no memory of her. The cop worries that Lai-chen may not even recognize him.

The exchange ends with a wordless shot of Yuddy sitting against the seat, eyes barely open, as an orchestral version of “Perfidia” rises up. The scene ends with an extreme long-shot of the train. The tune was heard earlier when the cop walked away from a nighttime encounter with Lai-chen, so this refrain reminds us of the cop’s yearning for her.

The alternate version doesn’t alter the overall situation much, but it presents different emphases. After the shot between the train cars, we have an off-center long shot of the cop; it’s then that we get the voice-over: “The last time I saw him, I asked him a question.” Cut to a medium close-up of Yuddy, which replaces the shot of the cop. Now for about two minutes he speaks and the cop’s reactions are kept offscreen.

As far as I can tell at this point, the dialogue is identical. In effect, we have a virtual shot/ reverse-shot exchange between the two films! And instead of holding on the framing of Yuddy, or cutting to the cop’s reaction, Wong simply gives us a shot of the two men in facing seats. This is followed by a very different shot of the train, winding through the sort of greenish-blue foliage seen in a famous earlier shot, and there is no music.

The international version puts the emphasis on the cop, who is both challenging Yuddy and obliquely reflecting on his own situation.; hence perhaps the “Perfidia” theme, which is associated with him. The alternate version keeps us focused on Yuddy throughout, our final stare at him, as it were, before a two-shot reasserts an equivalent weight between the two men, and perhaps their memories as well.

The very end

The variations continue in the final shots. Both versions begin with the shot of Lulu striding to the camera in a telephoto framing, above. Now she’s in the Philippines.

In the international version, this shot is followed by Lulu swanning into a bedroom, hanging up her dress, and saying to the landlady, “There’s someone I want to ask you about.”

In the other version, we see her passing through a somewhat sleazy hotel lobby and asking for a spare room. As a result, it’s somewhat less clear that she’s pursuing Yuddy.

The scene shifts to the stadium where Lai-chen works as a ticket seller. (Stephen Teo’s stimulating book on Wong specifies that it’s the South China Athletic Association.) Customers are swarming in for a football match. The obscure version gives us two quick tracking shots of the crowd, with the second ending on a profile shot of Lai-chen in her booth.

The standard version offers only one of the tracking shots and ends with a static framing of the profile composition. But this version adds a shot, beginning the scene with a head-on composition of her at her window.

At this point the alternate version omits two shots that have attracted a lot of critical commentary. Before the shot of Lai-chen shutting up shop, we see a high-angle view of tramway tracks and a shot of a clock outside the stadium.

The clock shot recalls Lai-chen’s meeting with Yuddy, while the tramcar lines recalls her rainy-night encounter with the cop. Instead of these empty shots, the alternate version cuts from Lai-chen in her booth to a shot of a soccer match, evidently seen through a slot in her cabin.

The rest of what follows corresponds in both versions. Lai-chen is seen reading a newspaper before closing the booth.

Both versions likewise wind down with a shot of the phone booth, the one that Lai-chen and the cop had lingered beside, followed by a closer view of the interior. The phone is ringing.

The first shot of the pair recalls, in its high-angle composition, the rainy night that the two met. (Wong’s characters are haunted by memory, but he forces us to use ours too.)

The cop had asked Lai-chen to call him, and the previous scene showed her closing her window, so we might infer that now she’s trying to get in touch with him—not knowing, as we do, that he’s quit the force, become a sailor, and watched her boyfriend die. But we can’t be sure that she’s the one making the call.

The very last shot, showing Tony grooming, is also the same in both versions. (One stage of it is at the very top of this entry.) It is a real crux. Why is Wong showing us this down-at-heel gambler for two and a half minutes? He has no evident connection to any of the characters we’ve followed, and we will never see him again.

Most critics have also accepted Wong’s explanation that he had planned a sequel, one showing how Yuddy’s influence over others lingered long after his death. Patrick Tam told Stephen Teo that the shot was his idea, a setup or trailer for the next film, turning everything we had seen up till now into a lengthy prologue. (1) But Days of Being Wild was a fiasco at the box office, taking in HK$9.7 million, or about $1.25 million US (in a year in which Stephen Chow’s All for the Winner earned over four times that). So the sequel was never made.

Yet these intriguing circumstances don’t really justify the epilogue’s purposes and effects. A causal explanation doesn’t necessarily yield a functional explanation. What role does this disruptive shot play in the film’s overall dynamic? If Wong had made the sequel, it might have been seen as a brilliant stroke; without the followup film, how can we justify its presence?

It’s reasonable to argue, as Teo does, that this vision of Tony’s primping generalizes Yuddy’s case, suggesting that his rootless narcissism is a condition of many young men of the day. You might also suggest that he provides a sort of male equivalent of the playgirl Lulu; just as the cop played by Andy Lau is a good, though unachieved, match for Lai-chen, Tony would pair up better with Lulu than Yuddy’s pal (Jacky Cheung), who pines for her.

Actually, the alternate version sheds a little light on the problem. It doesn’t provide a definitive answer to what Tony is doing there, but it does offer some tantalizing possibilities. In the alternate version, Tony is not only the last character we see, but the first one. And he’s embedded in a sequence that looks ahead to the style for which Wong has been both admired and castigated.

Languor and ellipsis

After the credits, the international version opens with Yuddy striding forcefully into the soccer stadium and mesmerically flirting with Lai-chen. But the print I examined of the obscure version interrupts the credits and shows us none other than the nameless young spark played by Tony Leung Chiu-wai, buffing his nails. (It seems to be an earlier stretch of the final shot, which continues this action.)

Over his image, we hear this in a male voice (no subtitles on the print):

I saw him one more time. He had just returned from the Philippines. He was much thinner than before. I asked him what happened to him. He replied that he just recovered from his sickness. He didn’t want to chat anyway, so I asked him what his sickness was.

Afterwards, we didn’t see each other any more.

This is very mysterious. Whose voice is speaking—Tony’s, Yuddy’s, Andy Lau’s? I can’t identify it. And who is the he referred to? The most plausible candidate is Andy, who may have returned to Hong Kong; and he is looking fairly ill in the film’s final scenes. But it might be the Tony character, as described by one of the other men, or even at a stretch Yuddy himself, who has somehow survived the shooting and returned to Hong Kong.

These ruminations assume that this opening shot frames a flashback by rhyming with the final image of Tony rising from the bed and dressing for his night out. It provides a sheerly formal justification for the final shot, which now completes the action begun at the start. But substantively, we’re still left with a variant of the original question. Instead of asking why end the movie with this remote character, we now ask why he’s used to frame the movie.

The questions have just begun, however. After this eighteen-second shot of the dapper Tony, we get a music montage lasting about eighty-three seconds. It’s quite perplexing. We’re in a warren of corridors, a bit reminiscent of the byways of Chungking Mansions in Chungking Express, and everything is in slow motion. We follow Andy Lau, in a yellow pullover, striding through the darkness and sweating profusely. Then we find him playing cards with some unidentified men. At one point, we see a woman climb the stairs, at other points we glimpse a man with an enormous snake coiled around him. The sequence ends with shots of a hand seizing a cleaver and shots of Andy, back in the corridor, striding away from us. The whole sequence is accompanied by the song “Jungle Drums,” which continues from the shot in Tony’s apartment but is now sung by a female voice (Anita Mui’s).

I was able to take stills of these shots, so I’ll go through them one by one, despite their iffy quality. (The images are very dark, and the print was worn and a little speckled.) After the opening shot of Tony, we get eighteen shots, all in slow-motion, many out of focus, and nearly all using camera movement. Often the cuts are matched in the normal fashion, but sometimes the connection is purely kinetic. As often in Wong’s work, the timing of the cuts synchronizes with beats or melodic lines in the music.

The first shot shows a woman ascending a staircase (pre-echo of the cheongsams in In the Mood for Love), and we pan quickly to Andy looking up after her before setting out down the corridor, where he passes a man with a snake.

Track left with Andy in medium close-up, wiping sweat from his face, then cut to an out-of-focus shot of him still walking.

Andy rounds a corner and proceeds down the hall, extending his hand to the wall. In one of those pseudo-matches, another hand slides open a door, as if completing his gesture. We see a card game inside. The framing suggests Andy’s point of view, but the camera glides back.

In close-up, a hand holds a cigarette. A slight tilt and rack-focus reveals that the card player is Andy.

Suddenly, there’s an out-of-focus shot of the snake sliding along the man’s arm; the shot lasts only 16 frames, or two-thirds of a second. (Here I go again, frame-counting.) This is followed by a blurry shot, only 19 frames, of Andy turning his head. It’s almost as if the snake-shot had attracted Andy’s peripheral vision.

The man with the snake, still out of focus, rises and goes behind a curtain. Cut to a shot of a light bulb shielded by a scrap of paper, with cigarette smoke wafting up.

A classic misterioso shot: A powerfully built man in a suit, seen from the rear, dominates the composition, and the camera tracks back from him. But instead of revealing his identity, the narration cuts back to Andy, who, out of focus, turns back to the game.

A new phase of the sequence starts. The camera pans up a rock wall, showing water trickling down it. Confirming that we’re back in the corridor, we see a hand seizing a chopper from a wall rack. There’s an odd effect of matching movement, with the pan upward picked up by the upward-lifting movement of the cleaver.

From another angle, the hand draws the cleaver across the frame.

Now we get opposing lines of movement—up and to the right in the first chopper shot, horizontally to the left in this shot. The rhythmic bump is accented by the brevity of the shots (30 frames, 21 frames). At the end of this second shot, we can glimpse someone walking away in the dark background.

The cleaver shots are followed by a close-up of Andy walking along the corridor, much like those at the start of the sequence. The final shot shows him walking far away from us. This take seems to be a continuation of the earlier one, when he put out his hand against the left wall. It fades out as the song does.

After the fade-out of Andy walking down the corridor, the credits resume and the scene introducing Yuddy and Lai-chen begins the main plot.

Wong had used a music montage in As Tears Go By (the remarkable “Take My Breath Away” sequence, which I analyzed in Planet Hong Kong). But there it functioned as a lyrical commentary on a sharply delineated, somewhat conventional narrative situation: Wah visits Ngor in Lantau Island and awkwardly communicates his affection for her. This sequence in Days is puzzling because it doesn’t have very clear narrative import. It does set the mood of languor that dominates the film, but it also hints at a situation of criminal danger (gamblers, the hand with the chopper) that is never actualized in the story that follows.

Coming after the fairly opaque opening shot of Tony, this sequence poses other questions. We’ll later learn that Andy is a diligent patrolman; what’s he doing in this den of thieves? Local audiences would recognize the location as the Kowloon Walled City, a sort of island of sheer criminality in the middle of Kowloon. Was Andy an undercover cop before taking up the uniform?

And who is seizing the cleaver? At first I thought it was Andy, but closer inspection shows that’s not likely; there’s nothing in his hands in the final extreme long-shot. Is someone stalking him? We never find out.

Wong is fond of giving us mere impressions of events, sometimes linked to characters’ consciousness, sometimes soaring cadenzas of images blended with music. But unlike the music montage of As Tears Go By and those in later films, this one is almost indecipherable in story terms. Nothing else in Days of Being Wild is as free-form as this stretch of footage. It can stand as an emblem and limit-case of Wong’s interest in using genre conventions poetically, and his reluctance to pay them off in plot terms.

Partial solutions, more mysteries

Back in 2001, Shelly Kraicer, impresario of the Chinese Cinema List, wrote about having seen this version, and several people chimed in with their recollections and opinions. In 2004, I asked several Hong Kong friends about it. Filmmaker, critic, and educator Shu Kei, who has a long memory for Hong Kong film, replied:

I remember the footage you describe. If I’m right, this was the version WKW re-edited after the disastrous midnight premiere of the film, and it was the “official released version” for the regular shows in the following week.

Days was released on 15 December 1990 and played until 27 December, so perhaps this was indeed the version that was seen in its Hong Kong run. In 2001 correspondence on Shelly’s list, Bérénice Reynaud, who saw the “pre-premiere version” of a print straight from the lab, was “positive” that the prologue material was not in that print.

Shu Kei offers some further information about the gambling sequence:

The shots with Andy Lau in a card game and fighting afterwards [sic] were done in a very early stage of the film’s lengthy shoot, in which Lau was playing a gangster-like character in the Kowloon Walled City. (The role, and much of the original concept of Days of Being Wild, were reprised in Jeff Lau’s Days of Tomorrow, 1993.) Andy’s character was later changed to that of a cop.

Two other Hong Kong observers told me that the revised version was designed to make sure that the big stars Tony Leung and Andy Lau had early and prominent entrances, since without the prologue, they play minor roles. Michael Campi reported in the 2001 correspondence: “I was told that in a frantic attempt to retrieve some revenue from the film, it was decided crassly to include Leung Chiu-wai in the opening as well as the closing.”

If this was the strategy, it’s reminiscent of the changes made to the international (originally, Taiwanese) version of Ashes of Time, with the prologue and epilogue showing explosive fighting scenes. Those passages were designed, explains Hong Kong Film Festival programmer Li Cheuk-to, to assure viewers that there would be swordplay in this rather talky movie.

Things are far from settled, though. The prologue is a major crux, but assuming that the last reel I saw was that of the 1990 retooled version, how do the circumstances outlined above explain the disparities in the endings? Why would audience dissatisfaction or producers’ demands force Wong to eliminate the empty shots of the stadium and the clock? Or substitute a different (and more opaque) scene of Lulu in the Philippines? Or change the découpage of the train dialogue between Yuddy and the cop? Or supply a different long shot of the train? Or eliminate the haunting “Perfidia” theme?

Moreover, we still don’t know what the premiere version screened at midnight shows was like. Was it congruent with today’s international version, or was it yet a third variant? In other words, did Wong un-revise the original, or re-revise it? At what point did he or his distributors replace the obscure version with the one in general circulation?

Earlier in June our blog discussed Grover Crisp’s visit to Madison, in which he argued that in an important sense every film exists in alternative versions. We simply have to accept that. It’s especially true of Hong Kong films, which are recut for circulation in many markets. And I like knowing that there’s an especially puzzling variant of Days of Being Wild—one that lets us imagine virtual narrative possibilities and adds to the appeal of this enigmatic movie. Nonetheless, I’d welcome more information about all this, especially from Wong Kar-wai himself.

(1) Stephen Teo, Wong Kar-wai (London: BFI, 2005), 45.

Thanks to Alex Wong for translating the prologue’s voice-over narration for me.