Archive for the 'Directors: Kuleshov' Category

B is for Bologna

A big crowd assembles for one of the nightly screenings on the Piazza Maggiore.

Not laziness or old age (we hope) but sheer busyness has reduced our Bologna blogging to a single entry this year. Last year we managed three entries, but this time there was just so much to see, from nine AM to midnight, that we couldn’t drag ourselves away to the laptop. That it was blazing hot and surprisingly humid may have given us less biobloggability as well. Still, DB has many pictures, so maybe a followup blog with unusual images of critics and historians disporting in the sun….

Some backstory: Hosted by the Cineteca of Bologna, Il Cinema Ritrovato is an annual festival of rediscovered and restored films. Every July hundreds of movies are screened in several venues. For our 2007 report, with more background and some orienting pictures, go here and then here and here. Watch a lyrical trailer for the event here.

As before, both KT and DB contribute to this year’s entry. But first, the breaking story.

Freder and Maria, together again for the first time

While we were there, the news of a long version of Metropolis broke. The estimable David Hudson offers a quick guide and an abundance of links at GreenCine. A rumor went around Bologna that fragments of the new Buenos Aires print would be screened, but instead there was a twenty-minute briefing anchored by Martin Koerber of the Deutsche Kinemathek. Along with him, Anke Wilkening (Friedrich-Wilhelm-Murnau Stiftung), Anna Bohn (Universitat der Kunste, Berlin), and Luciano Berriatua (Filmoteca Espanola) provided some key points of information.

*Provenance: The “director’s cut” was released in Argentina during the 1920s, with Spanish intertitles and inserts made at Ufa. A collector acquired a print. (Once more we have a collector to thank for saving film history.) When the Argentine film archive (Museo del Cine Pablo C. Ducros Hicken) received the copy in the 1960s, a 16mm dupe negative was made, and the nitrate original was discarded, a common practice at the time.

*Condition of the copy: The print is very worn, as the frame reproduced by Die Zeit indicates. Can the torrent of lines and scratches be eliminated? The rescue isn’t likely to be perfect; the damage is perhaps “beyond the reach of our algorithms,” as Martin puts it. To my eye, judging from the Die Zeit frames, many images are lacking in texture and contrast as well.

*Condition of the copy: The print is very worn, as the frame reproduced by Die Zeit indicates. Can the torrent of lines and scratches be eliminated? The rescue isn’t likely to be perfect; the damage is perhaps “beyond the reach of our algorithms,” as Martin puts it. To my eye, judging from the Die Zeit frames, many images are lacking in texture and contrast as well.

*Completeness: Contrary to some reports, virtually all the missing scenes are present on the Argentine print, the single exception being a small portion at a reel end. Among the new sequences are scenes filling in the roles of three characters (Georgy, Slim, and Josaphat), a car journey through the city, and moments of Freder’s delirium.

How can the researchers be confident that the print is so complete? It’s a fascinating story.

Metropolis has been reconstructed many times since the 1960s. In 2001, the Murnau foundation presented a digital restoration of the film supervised by Martin Koerber in collaboration with Enno Patalas. In this version, which is available on DVD (Transit Film, Kino International) about 30 minutes of the original material are missing. In 2003-2005 Enno Patalas and Anna Bohn together with a team at the University of the Arts in Berlin created a “Study Edition” version in which the missing footage was represented by bits of gray leader. For the first time the full length of the film was reconstructed with help from the the original music score.

In 2006 a “DVD study edition” was released by the Film Institute of the Berlin University of the Arts (Universität der Künste Berlin; DVD-Studienfassung Metropolis). This scrupulous version includes the original score, a lot of production material, and the complete script by Thea von Harbou. It’s a model of how digital formats can assist documentation of film history. The DVD incorporates production stills and intertitles from the missing scenes, and presents each scene in its original duration (sometimes with only gray leader onscreen). The editors determined the duration of each scene by a critical comparison of the remaining film materials with the music score and other source materials. This DVD edition was released in a limited edition available to educational and research facilities. For information see here or here.

In 2006 a “DVD study edition” was released by the Film Institute of the Berlin University of the Arts (Universität der Künste Berlin; DVD-Studienfassung Metropolis). This scrupulous version includes the original score, a lot of production material, and the complete script by Thea von Harbou. It’s a model of how digital formats can assist documentation of film history. The DVD incorporates production stills and intertitles from the missing scenes, and presents each scene in its original duration (sometimes with only gray leader onscreen). The editors determined the duration of each scene by a critical comparison of the remaining film materials with the music score and other source materials. This DVD edition was released in a limited edition available to educational and research facilities. For information see here or here.

Bohm and Patalas’s comparative method proved itself valid: The Buenos Aires footage fitted the gaps in their study edition perfectly!

A viewing copy will not be forthcoming immediately, given the restoration task, but sooner or later we will have a good approximation of the fullest version of one of the half-dozen most famous silent movies. Getting news like this while among archive professionals is one of the unique pleasures of Cinema Ritrovato. (Special thanks to Dr. Bohn for clarification on several points and to enterprising film historian Casper Tybjerg, who helped me get a copy of the Die Zeit issue.)

Two Davids and a Kevin: Robinson, Brownlow, and Shepard at a critics’ lunch.

Powell meets Bluebeard and Bartók

KT: One of the high points of the week for me was Michael Powell’s 1964 film of Béla Bartók’s short opera Bluebeard’s Castle. It was made for German television and shown in Bologna as Herzog Blaubarts Burg. Unfortunately it was programmed opposite the screening of fragments from Kuleshov’s Gay Canary, but Powell’s post-Peeping Tom films are so difficult to see that I made the difficult choice and gave up hope of seeing the entire Kuleshov retrospective.

Despite being relatively recent in comparison with most of the films shown during the week, Herzog Blaubarts Burg is one of the most obscure. I felt it was an extremely rare privilege to see it, one which I will probably never have again, at least in so splendid a print.

The film belongs to the late period of Powell’s career, after the controversial Peeping Tom had made it impossible for him to work within the mainstream film industry. It was produced by Norman Foster—though not the Norman Foster who directed Journey into Fear and several of the Charlie Chan and Mr. Moto films. This Norman Foster was an opera singer whose stage career was cut short by a dispute with Herbert von Karajan. His widow, Sybille Nabel-Foster, explained this and described how Foster produced and starred in two television adaptations, Herzog Blaubarts Burg and Die lustigen Weiber von Windsor (1966). Foster had originally approached Ingmar Bergman to direct the former, but when that proved impossible, Powell stepped in—and probably a good thing, too. It was definitely his kind of project.

The two performers are perfect for their roles. Foster plays Bluebeard brilliantly, having both a powerful bass voice and the necessary combination of handsomeness and a sense of threat. His co-star, the excellent soprano Ana Raquel Satre, recalls the pale beauties of some of Powell’s earlier films (Kathleen Byron as the increasingly mad Sister Ruth in Black Narcissus, Pamela Brown in I Know Where I’m Going!, and particularly Ludmilla Tcherina in The Tales of Hoffman), but she also bears a resemblance—perhaps deliberately enhanced through costuming and make-up—to Barbara Steele and other horror-film heroines of the 1960s.

The film was shot cheaply in a Salzburg studio, using garish, modernist settings against black backgrounds. These create a labyrinthine, floating space that avoids seeming stage-bound. (Hein Heckroth, the production designer, had previously worked on several Powell films, including The Red Shoes and The Tales of Hoffman.) I was reminded of Hans-Jürgen Syberberg’s Parsifal (1982), which looks somewhat less original in the light of Powell’s film.

As Nabel-Foster explained, after its initial screening on German television, Herzog Blaubarts Burg has been shown seldom because of rights complications with the Bartók estate. Non-commercial screenings have occurred on public television in the U.S. and Australia, but basically the film is off-limits until the copyright expires in 2015, seventy years after the composer’s death. Nabel-Foster has been providently preparing for a DVD release, gathering the original materials.

The print shown was a privately held Technicolor original from the era, in nearly mint condition. (The British Film Institute has a print as well.) The sparse subtitles written by Powell himself were added for this screening.

I’m not convinced that the film is quite the masterpiece that some claim, but it is a major item in Powell’s oeuvre nonetheless, and I felt privileged to have seen it in ideal conditions.

[July 12: Kent Jones, a great admirer of Powell and Bluebeard’s Castle, tells me that he programmed it at the Walter Reade in New York for a centenary retrospective of the director’s work in 2005. Foster’s widow introduced that screening as well.]

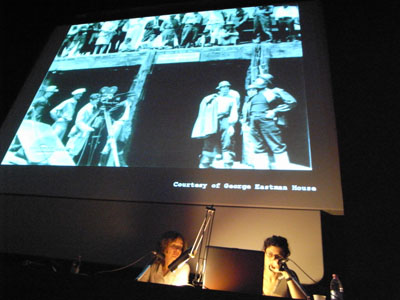

Janet Bergstrom and Cecilia Cenciarelli summarize their research on von Sternberg’s lost film The Sea Gull.

1908 and all that

KT: There were several programs of silent shorts, which I could only sample, as they tended to play opposite the Kuleshov films. As usual, the Bologna program included selections of short films from 100 years ago, so we were treated to numerous films from 1908. I was particularly pleased to see The Dog Outwits the Kidnappers, directed by Lewin Fitzhamon, who had made Rescued by Rover two years earlier. That film had been so fabulously successful that it had actually been shot three times as the negatives wore out from the striking of huge numbers of release prints.

The Dog Outwits the Kidnappers at first appears to be a sort of sequel (as it is described in the program), since it stars the same dog (Blair) who had played Rover, and again there is a kidnapped baby. It’s not really a sequel, though, since Cecil Hepworth, who had played the father in the earlier film, here appears as the kidnapper, and the dog is not named Rover. The new film is more fantastical than the original, since the dog races after the car in which the child is abducted and rather than fetching its master, effects the rescue itself by driving the car back home when the villain leaves his victim unattended!

Other 1908 films I particularly enjoyed: In Pathé’s Le crocodile cambrioleur, a thief hides inside a huge fake crocodile and crawls away, creating fear wherever he goes. The Acrobatic Fly by British director Percy Smith, provides a very close-up view of an apparently real fly juggling various small objects. (How was it done? It’s a mystery to me.)

Another retrospective series was “Irresistible forces: Comic Actresses and Suffragettes (1910-1915).” The suffragette films were rather depressing, despite the fact that many were meant at the time to be comic and amusing. Mostly the joke was how masculine these determined women were, a self-verifying proposition when the filmmakers often chose to have the suffragettes played by men. My favorite program was one involving early French female comics. I’ve long been fond of Gaumont’s Rosalie series since seeing a few at an early-cinema conference in Perpignon, France back in 1984. Rosalie, a chubby, cheerful little dynamo played by Sarah Duhamel, was highly entertaining in three films in the “France—Rosalie, Cunégonde et les autres…” program.

As Mariann Lewinsky, who devises these annual series, pointed out, Duhamel is the only early female French comic whose name we know. Léotine, represented here in Rosalie and Léotine vont au théâtre, is played by an anonymous actress. I had not encountered Cunégonde, also anonymous, before, but she proved to be quite amusing as well. I particularly liked Cunégonde femme du monde, where she plays a maid who dresses up as a society lady when her employers go off on a trip; the carefully constructed story and twist ending are impressive for such an apparently minor one-reeler.

It was a treat to see a succession of gorgeous prints of von Sternberg’s films. I particularly enjoyed seeing Thunderbolt (1929) again after many years. Back in 1983 I taught a survey film history course in which I used the director’s first talkie as my example of the transition to sound. Not a good example, I must admit, since Thunderbolt is completely atypical, with its highly imaginative use of offscreen sound. The second half, set primarily in a prison block, involves shouts from unseen cells and a small band that breaks into songs, often completely out of tone with the action, at unexpected moments. Eisenstein and the other Soviet directors would have thoroughly approved of its sound counterpoint. I have to admit that I prefer von Sternberg’s George Bancroft films (Underworld, Docks of New York, and Thunderbolt) to the Dietrich ones. Not only are the plots simpler and more elegant, but they contain a genuine element of emotion that is not, as in the Dietrich series, frequently undercut by irony.

I didn’t make it to many of the CinemaScope films playing on the very big screen in the Cinema Arlecchino theater, but I did enjoy two westerns. Anthony Mann’s Man of the West (1958) and John Sturges’ Bad Day at Black Rock (1954) both looked terrific and were highly popular with everyone we talked to. The latter was particularly a revelation, since in contrast to the Mann, it hasn’t had much of a reputation among cinephiles.

A Rodchenko angle for Yuri Tsivian.

Teacher and experimenter

DB: As Kristin mentioned, we missed a lot of the “Hundred Years Ago” series—a pity, since 1908 is a miraculous year—in order to keep up with one of our favorite directors, Lev Kuleshov.

In the 1960s and 1970s, it was common to say that Eisenstein and Vertov were the most experimental Soviet directors, while the others were more conventional. Then we realized that in films like Arsenal (1928), Dovzhenko had his own wild ways. Then we discovered the Feks team, Kozintsev and Trauberg, and the bold montage of The New Babylon (1929). A closer look at Pudovkin, particularly his early sound films like A Simple Case (1932) and Deserter (1933), revealed that he too was no timid soul when it came to daring cutting and image/ sound juxtapositions. But surely their mentor Kuleshov, admirer of Hollywood continuity and proponent of the simplest sorts of constructive editing, played things safe?

Wrong again. Just as we must reevaluate the other master Soviet directors (even in their purportedly safe Stalinist projects), so too does Kuleshov deserve a fresh look. He got this thanks to Yuri Tsivian, who with the help of Ekatarina Hohlova (right; granddaughter of Kuleshov and his main actress Aleksandra Hohlova) and Nikolai Izvolov, mounted a superb retrospective. It ranged from Kuleshov’s first solo effort, Engineer Prite’s Project (1918) to his final film, the short feature Young Partisans (1942-3, never released).

Wrong again. Just as we must reevaluate the other master Soviet directors (even in their purportedly safe Stalinist projects), so too does Kuleshov deserve a fresh look. He got this thanks to Yuri Tsivian, who with the help of Ekatarina Hohlova (right; granddaughter of Kuleshov and his main actress Aleksandra Hohlova) and Nikolai Izvolov, mounted a superb retrospective. It ranged from Kuleshov’s first solo effort, Engineer Prite’s Project (1918) to his final film, the short feature Young Partisans (1942-3, never released).

My admiration for Kuleshov, confessed in an earlier blog entry, already led me to spot some weirdnesses in Mr. K’s official classics. The Extraordinary Adventures of Mr. West in the Land of the Bolsheviks (1924) boasts some very un-formulaic cutting in certain passages (including an upside-down shot when cowboy Jeddy ropes the sleigh driver), and By the Law (1926) makes chilling use of discontinuities when the scarecrow Hohlova holds the Irishman at gunpoint. But thanks to the retrospective we can confidently say that Kuleshov was no less venturesome, at least in certain projects, than his pupils.

Soviet specialists already suspected that The Great Consoler (1933) was K’s sound masterpiece, and another viewing confirmed it. It incorporates three registers. William S. Porter, in prison but serving in the pharmacy, witnesses brutality and oppression and is driven to drink. Under the name O. Henry he writes cheerfully sentimental tales as much to console himself as to charm readers. His stories are in turn consumed by shopgirls like Dulcie, a romantic who may not realize how unhappy she is. Kuleshov adds a level of sheer fantasy, represented by a pastiche silent film dramatizing O. Henry’s “A Retrieved Reformation,” in which a safecracker trying to go straight reveals his identity by saving a girl trapped in a bank vault. The embedded story features characters from the other two levels, convict Jimmy Valentine and Dulcie’s lover, a vaguely sadistic businessman in a ten-gallon hat.

The Great Consoler reminds us of the popularity of O. Henry in the Soviet Union, both among readers and the Russian Formalist literary theorists, who were fascinated by his flagrant, playful artifice. (Boris Eikhenbaum’s essay on the writer is one of the most brilliant pieces of literary analysis I know.) Even though Kuleshov must denounce Porter for reconciling the masses to their misery under capitalism, the zest of the embedded film and the unique architecture of the overall project pay tribute to another entertainer who did not forgo experimentation. And Kuleshov’s image of a writer in prison probably had Aesopian significance for artists in the era of Socialist Realism.

K’s other major sound experiment, less widely seen, is Gorizont (1932). The title is at once a man’s name and the Russian word for “horizon”—a metaphor literalized in the final shot of a train leaving a tunnel. As Yuri pointed out, it is one of the few Soviet films centered on a Jew, and so the formulaic growth-to-consciousness plotline takes on a new resonance in the light of Slavic anti-semitism. Lev Gorizont is an amiable, somewhat thick young man who dreams of emigrating to the US to make his fortune. But in New York he finds only poverty and disillusionment, eventually returning home to help make a better society. Famous for its use of sound, Gorizont contains a passage of imaginative “counterpoint.” Both Lev and his friend Smith have been jilted by the social-climber Rosie. As they talk, we hear warm piano music, but not until the end of the scene does Smith speculate that probably Rosie is somewhere listening to Chopin. The music has retrospectively functioned somewhat like crosscutting, suggesting that Rosie now lives among the wealthy.

Kuleshov, like Eisenstein, gained his fame for his ideas on editing and sound montage, but both men were deeply interested in performance. Kuleshov’s idea that the film actor should become an angular mannequin carries on the impulse of Meyerhold’s biomechanics, and he anticipated CGI software in suggesting that human action could be plotted on a three-dimensional grid. Still, Kuleshov usually gives his figures a fluid dynamism that doesn’t seem mechanical. The three narrative registers of The Great Consoler are delineated largely through acting: naturalistic and slowly paced in the prison scenes, rigid and posed in the shopgirl romance, and broad and eccentric in the embedded silent movie.

Kuleshov’s performance theories popped out of other films in the series. What survives of The Gay Canary (1929) centers on a cabaret actress courted by lustful reactionaries during the civil war, and her scenes of fury, as she flings around flowers, vases, and pieces of furniture, come off as acrobatic rather than realistic. Naturally, the circus milieu of 2 Buldy 2 (1929) encourages stunts. A father and son, both clowns, are to perform together for the first time, but the civil war separates them, and the elder Buldy, tempted for a moment to acquiesce to the White forces, casts his lot with the revolution. At the climax Buldy Jr. escapes the Whites thanks to flashy trampoline and trapeze acrobatics; the gaping enemy soldiers forget to shoot. Even Kuleshov’s more naturalistic films show flashes of kinetic, stylized acting. A partisan listens to a boy while draping himself over a door. A Bolshevik official answers the phone by reaching across his chest, twisting his body so the unused arm can hike itself up, right-angled, to the chair.

The interaction of the body with props occurs with a special flair in Young Partisans. A Bolshevik partisan tells some children how a boy saved his life in a German-occupied town (This flashback was directed by Igor Savchenko and functions as a short film on its own.) Having learned their lesson, the kids gather in their schoolroom and under the teacher’s eye draw a map of the partisans’ camp. But when Nazi soldiers burst in, the teacher flips the blackboard over; now all we see is algebra.

A scene of Hitchcockian suspense ensues: Will the Germans turn over the blackboard and discover the map? The tension is enlivened by a grotesque moment, when one alcoholic soldier finds a jar holding a pickled frog and decides to drink the formaldehyde. “Draw a map—show me where the partisans are!” the officer demands. He flips the blackboard, and in a split-second we see a boy crouching behind it; the blackboard swings into place toward us, the map now erased. The boy ducks into his seat, brushing off chalk dust.

There were plenty of other revelations. We got the reconstructed Prite (was it the first really modern Soviet film?), a bit of an original Kuleshov experiment in constructive editing, and a tantalizing fragment from The Female Journalist (1927), with a surprisingly pensive Hohlova as a modern-day reporter. Sasha (1930), directed by Hohlova herself, was a sympathetic portrait of a pregnant woman. An educational film called Forty Hearts (1930) explained the need to electrify the Soviet countryside and was brightened by faux-naïve animation. Timur and His Crew (1942), with some of the charm of a Nancy Drew movie, showed Young Pioneers helping on the home front; it unexpectedly centered on a girl’s devotion to her military father.

There were plenty of other revelations. We got the reconstructed Prite (was it the first really modern Soviet film?), a bit of an original Kuleshov experiment in constructive editing, and a tantalizing fragment from The Female Journalist (1927), with a surprisingly pensive Hohlova as a modern-day reporter. Sasha (1930), directed by Hohlova herself, was a sympathetic portrait of a pregnant woman. An educational film called Forty Hearts (1930) explained the need to electrify the Soviet countryside and was brightened by faux-naïve animation. Timur and His Crew (1942), with some of the charm of a Nancy Drew movie, showed Young Pioneers helping on the home front; it unexpectedly centered on a girl’s devotion to her military father.

One of the biggest surprises was news of Dokhunda (1936), an ethnographically based fiction set in Tazhikistan. Although the film is lost, Nikolai has reconstructed its plan, revealing that Kuleshov adopted a strange preproduction method. He prepared “living storyboards,” photos of the cast enacting the scenes. He then drew and scratched on them, creating busy, nervous backgrounds or changing the figures’ features and hair styles—Kuleshov as pre-Warhol scribbler, or a graffiti artist tagging his own images.

Nikolai has also finished a DVD edition of Prite that exemplifies what he calls hyperkino, a way of annotating and comparing a film’s images, texts, and supplementary materials for instant access. Another project involves the Yevgenii Bauer classic, The King of Paris (1917), which Kuleshov completed. We haven’t had the intertitles for this, however, but now Nikolai has discovered them, and they will go on the DVD version that is being completed. For more information on these projects and Dokhunda, go to hyperkino.net.

So Kuleshov stands revealed as more supple and ambitious than most of us once thought. Once more Bologna plays to its strengths—filling in gaps but also forcing us to rethink what we thought we knew.

The key issue: What the hell am I going to be seeing now? From left, Olaf Muller, Jonathan Rosenbaum, Don Crafton, Haden Guest, and KT.

So much else to report, so little time. Besides The King of Paris, there was a string of fine 1910s films. Raoul Walsh’s Pillars of Society (1916), while not a patch on his Regeneration of the previous year, offered a solid adaptation of Ibsen. The Dawn of a Tomorrow (1915), James Kirkwood’s Mary Pickford vehicle, seemed to me flat and talky, but others liked it. For me the outstanding item was Paul Garbagni’s In the Spring of Life (1912). Beautifully directed in the tableau style, with precise depth choreography and a stirring scene of a theatre consumed by fire, it starred three men who would become great directors very soon: Sjöström, Stiller, and Georg af Klercker.

Not to mention the von Sternbergs (I liked An American Tragedy much more on this outing), the Scope revivals (Man of the West, Ride Lonesome in a handsome digital restoration from Grover Crisp), my first viewing of Duvivier’s La Bandera (1935), the Monta Bell items (most notably the incessantly energetic Upstage from 1926), and on and on.

What can Gianluca Farinelli, Peter von Bagh, and Guy Borlée, along with their devoted staff members, do for an encore? Bravo! Now take a rest.

Standing Room Only for the rarely seen Children of Divorce (Sternberg/ Lloyd, 1927).

What happens between shots happens between your ears

DB here:

In Number, Please? (1920) Harold Lloyd plays a lovesick boy who’s been jilted by his girl. Moping at an amusement park, he sees her arrive with a new beau.

He shifts to another spot to watch them. When she notices him, she scorns him, and he reacts.

She and the escort stroll past, then she turns and cuddles up to him, making sure Harold notices.

Her flirting precipitates the rest of the action in this very funny short.

In this scene from Number, Please? Harold and the couple aren’t shown in the same frame. The action is built entirely out of singles of Harold and two-shots of the couple, with an especially emphasized close-up of the girl’s snooty reaction. The sequence is rapidly paced and carefully matched in angle; note the shift in eyelines as the girl and her beau walk a little way and then she looks back at Harold.

This approach to building a scene was consolidated in American studio cinema in the late 1910s, as we noted recently, and it soon spread around the world. One of the places it caught on most fervently was Soviet Russia.

Kuleshov glories in the gaps

The great director and theorist Lev Kuleshov always claimed that he and his associates learned the power of editing from American cinema. Russian films were slowly paced, consisting of long tableaus occasionally broken by an inserted closer view of an actor. (For examples, see my Bauer blog entry from the summer.) Kuleshov noted that the Hollywood films brought into Russia grabbed audiences’ interest more intently, and Kuleshov attributed this effect to the fact that the Americans exploited editing more fully, creating the scene out of many shots.

Kuleshov’s example was the formulaic scene of a man sitting at his desk and deciding to commit suicide. The Russians, Kuleshov claimed, would handle this all in one distant framing, with the result that the key actions were just part of the overall view. By contrast, Americans would shoot the scene in a series of close-ups: the man’s face, his hand taking a pistol out of a desk drawer, his finger tightening on the trigger, and so on. This gave the scene a powerful concreteness, and was cheaper to film besides (no need to have a full set).

But most American filmmakers didn’t create the scene wholly out of close-ups. Typically there would be an establishing shot before the action was broken down into detail shots. The process has come to be called analytical editing. (We discuss it in Chapter 6 of Film Art.) As the label implies, the cutting analyzes an orienting view into its important details.

Less commonly, as in our Number, Please? example, American directors could create a scene entirely out of separate areas of space, without ever showing a master framing. This technique, usually called constructive editing, remains common today as well, especially in action scenes.

While praising analytical editing, Kuleshov was particularly taken with constructive editing, because that shows that cinema can call on the spectator’s tacit understanding to assemble the separate shots. Kuleshov realized that we will build a sense of the scene’s space and action out of separate shots without need for the comprehensive view supplied by an establishing shot.

What the Americans developed, the Soviets thought seriously about. Around 1921, Kuleshov and his students mounted some experiments, several of which he discusses in his books and essays. He probably didn’t need to experiment; the American films were full of examples. Indeed, the Number Please? passage is more intricate than any experiment Kuleshov seems to have mounted. But he had a bit of the engineer about him, and he sought to break the technique into its simplest components.

For one thing, constructive editing offered production efficiencies. You could film two actors separately, at different times, and then cut them together. Further, Kuleshov saw that editing could abolish real-world constraints. It created events that existed only on the screen, with an assist from the viewer’s mind.

This is perhaps best seen in his experiment involving an “artificial person.” Evidently it wasn’t a case of constructive editing, because it seems to have begun with an establishing shot. The first shot shows a girl sitting at her vanity table putting on makeup and slippers. A series of close-ups of lips, hands, legs, and the like were derived from different women, and they were edited together to create the impression of a single woman. (Something of this effect survives in the idea of a body double in contemporary films and TV commercials.) But the point is that the woman on screen, made out of different parts, doesn’t exist in the real world.

The same possibility could apply to geography, if we delete the establishing shot. As Kuleshov describes his experiment, we initially get a shot of a woman walking along a Moscow street. She stops and waves, looking offscreen. Cut to a man on a street that is in actuality two miles away. He smiles at her and they meet in yet a third location, shaking hands. Then together they look offscreen; cut to the Capitol in Washington DC. Kuleshov saw the potential for imaginary geography as both a useful production procedure and a demonstration that editing could create a purely cinematic space, one not beholden to reality.

Kuleshov’s most famous experiment, the one he identified with the “Kuleshov effect” proper, involves a stock shot of the actor Ivan Mosjoukin, taken from an existing film. In his writing he’s rather vague and laconic about the results.

I alternated the same shot of Mosjoukin with various other shots (a plate of soup, a girl, a child’s coffin), and these shots acquired a different meaning. The discovery stunned me—so convinced was I of the enormous power of montage. (1)

Kuleshov’s pupil the great director V. I. Pudovkin offers a different description of the shots: a plate of soup, a dead woman in a coffin, a little girl playing with a teddy bear. He also goes farther in reporting how the audience responded. People read emotions into the neutral expression on Mosjoukin’s face.

The audience raved about the actor’s refined acting. They pointed out his weighted pensiveness over the forgotten soup. They were touched by the profound sorrow in his eyes as he looked upon the dead woman, and admired the light, happy smile with which he feasted his eyes upon the girl at play. But we knew that in all three cases the face was exactly the same. (2)

Now it isn’t only geography or a human body that has been created by editing; it’s an emotion.

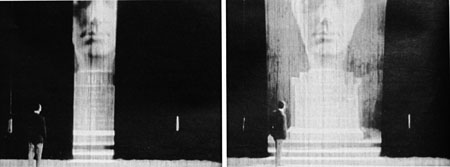

These experiments have been poorly documented, and only a couple have survived. One consists of fragments of the imaginary geography exercise. Here is Alexandra Khokhlova waving, but we don’t have the answering shot of the male actor responding. The two meet at the foot of a statue.

After the two shake hands, they look up and out of the frame, but unfortunately we lack the shot of the Capitol.

Kristin and other scholars have written more about these surviving fragments, and their essays are published along with Kuleshov’s proposal for funding the experiments and his wife Khokhlova’s memoir of filming them. (3)

It’s worth taking these prototypes of constructive editing apart a little bit. Clearly, there are several cues that prompt us to see the shots as continuous.

One cue is a common background, or at least a consistent one. Kuleshov thought that sometimes a neutral black background worked best, especially for close shots, as you can see with the handshake shot. Another cue is roughly consistent lighting from shot to shot. Yet another is the presumption of temporal continuity; no moments seem to be omitted in the cut from shot A to shot B. It never occurs to us to consider that Kuleshov’s man is looking at something hours or days before the soup is laid on the table in the second shot.

One of the most important cues goes unmentioned by Kuleshov: the very act of looking. Like most commentators, he seems to take it for granted. Yet it’s crucial in prompting us to imagine an overall space in which the actions take place. Knowing the real world as we do, we can infer that if you’re close enough to watch someone, both people are probably in a shared space, such as the arcade strip in the amusement park in Number, Please?

Another cue is facial expression. In his soup/girl/coffin sequence, Kuleshov supposedly picked a shot of Mosjoukin that doesn’t have a clearly identifiable expression. If Mosjoukin was smiling in his interpolated shot, he would presumably seem not grieving but wicked. Normally, though, performers seen in the single shot are expected to express the appropriate emotion more fully, in order to specify what we take the characters’ mental states to be. Our sequence from Number, Please? makes sure we understand the drama by giving the actors unambiguous expressions.

Finally, in the Kuleshov prototypes each shot should be simple. Its action can be stated in a brief sentence. A woman waves. A man responds. A man looks. A plate of soup sits on a table. Even in Number, Please? we can summarize each shot: Harold looks off. His former girlfriend disdains him. That’s to say that the shots are composed to present only one, quickly grasped point of interest.

Filmmakers don’t need to tease apart all these cues; they use them intuitively. Soon after Number, Please?, Hollywood filmmakers were creating amazing passages of eyeline-match editing—the most virtuoso being probably the racetrack sequence in Lubitsch’s Lady Windermere’s Fan (1926). Within a few years of Kuleshov’s experiments, Soviet filmmakers were creating their own masterworks, like Battleship Potemkin (1925) and Kuleshov’s By the Law (1926). Benefiting from a very compressed learning curve, filmmakers took constructive editing to new heights.

Constructive editing, dissolved relationships

Sometimes constructive editing is used to save a scene when production goes astray. When Doug Liman reshot the climax of The Bourne Identity, Julia Stiles couldn’t be on set, so singles of her taken from the first version were wedged in among the retakes, to create the impression that she was watching Jason confront his controller. More positively, a carefully calibrated constructive editing is central to a sequence I analyzed a while back in In the City of Sylvia. For over 100 shots, the spatial relations are built up without an overall establishing shot. (4)

Constructive editing can be used systematically throughout a film. A good example is Alan J. Pakula’s thriller Presumed Innocent (1990). Spoilers coming up!

Harrison Ford plays Rusty Sabitch, a prosecutor in the District Attorney’s office who becomes infatuated with a new woman on the staff. He has a brief affair with her, but after she’s broken it off she’s found brutally murdered. He has to investigate the crime without involving himself, but eventually he becomes the prime suspect.

At the start of the film before Rusty learns of the murder, Rusty and his wife Barbara are shown at breakfast, and establishing shots bring them together.

At the office Rusty learns of Carolyn’s death, and after he comes home, the conversation between Rusty and Barbara is treated without an establishing shot. Barbara knows about the past affair, and Rusty is wracked by guilt and shame. The cutting seems to reflect the fact that Carolyn’s death has revived the pain in their marriage.

In a series of flashbacks, Rusty relives his affair with Carolyn. Pakula treats their early encounters by means of constructive editing. The common-background cue is especially helpful in this scene in a kindergarten.

Only after Carolyn and Rusty cooperate and win a child-abuse case does the cutting’s rationale become clear. Pakula has saved the traditional two-shot framing for their moment of passion, as they make furious love in the office.

But soon their affair wanes and Rusty is reduced to watching Carolyn from across the street in point-of-view shots.

After the flashbacks end, Rusty is investigated and eventually charged with Carolyn’s murder. In these scenes Pakula often situates Rusty and Barbara in the same frame, as if the threat to him has healed the breach between them.

Yet in the film’s climax—and here is the big spoiler—they are pulled apart again. The last scene is a sustained monologue by Barbara. As Rusty listens, across twenty-six shots the two are never shown in an establishing shot.

Contrary to the standard Hollywood ending, in which the loving couple embrace in reunion, here they are left divided.

Pakula’s use of constructive editing has effectively traced two arcs: the growth and dissolution of Rusty’s affair, and the reuniting and dissolution of his marriage. In such ways, what might seem a purely local effect, confined to a handful of shots, can create stylistic patterning across a film. The judicious use of constructive editing matches the dramatic development.

Godard of the gaps

Robert Bresson has made more varied and complex uses of constructive editing across a film, as I tried to show in Narration in the Fiction Film and in an Artforum essay. (5) A more radical approach, somewhat in the purely Kuleshovian spirit, can be seen in Godard’s films since the late 1970s. In presenting a scene, Godard often omits an establishing shot, so constructive editing takes over. But he makes the technique quite abrasive and ambivalent.

In watching films like Number, Please? and Presumed Innocent, we fill in the gaps between shots with ease. Godard, however, makes his images and sounds more fragmentary by equivocating about the Kuleshovian cues. The background elements and lighting don’t match entirely; time seems to be skipped over; glances and facial expressions are ambivalent. Adding to these factors, lines of dialogue slip in from offscreen. Godard does present a dramatic scene taking place, but he also creates a sense that images and sounds have been pried loose from their place in an ongoing action, floating somewhat free and functioning as objects of contemplation for their own sake. The cues that Lloyd insists on and that Kuleshov plays with are ones that Godard suppresses or makes ambiguous.

I’ve mentioned this tendency in a recent entry, but to elaborate a little, consider the science lecture in Hail Mary (Je vous salue Marie, 1985). A professor who has emigrated from an Eastern bloc country is explaining his theory that life on earth began and evolved because it was directed by extraterrestrials. No establishing shot of the classroom shows us where he, Eva, and two male students are located, so we have to construct a rough sense of their positions on the basis of a few cues. As Eva, perched on a windowsill, toys with a Rubik’s cube, we hear the professor’s lecture begin to speculate on whether life could have evolved spontaneously. His remarks about sunlight coincide with a burst of sun on her face.

After the Biblical title, “In those days,” we get a series of shots that allow us to apply our mental schema of a classroom lecture: attentive students looking off, a professor at the blackboard.

Lacking an establishing shot, we can’t specify how many people are in the class, nor indeed where Eva and her classmate are sitting—since the professor looks off in several directions during his talk.

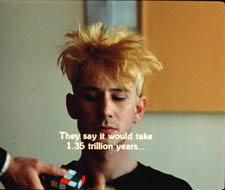

At the end of his talk he remarks, still scanning the room, that we can presume that life exists in space. “We come from there.” At that point Godard cuts to the head of another student, seen from behind. The sproingy haircut is a little explosion of yellow, and it’s accompanied by a burst of choral music. And as the shot goes on, we start to notice that the professor is pacing in the background, out of focus.

The student, whom we’ll learn is named Pascal, asks a question (at least the slight head movement suggests that it comes from him), and the professor replies. Pascal scratches his head as the professor continues, still out of focus. If I had to choose one shot that condenses Godard’s strategy of suppression in this sequence, this shot would be my candidate.

At the end of the shot, the professor asks Eva to stand behind Pascal. Cut 180 degrees and somewhat farther back to Pascal, now seen from the front. The professor’s hand brings the Rubik’s cube into the shot and Eva comes up behind Pascal as the professor passes.

Later she and the prof will become lovers, but Godard lets them meet first as simply two torsos intersecting behind Pascal. The purpose is a demonstration that a “blind” agent can be steered toward a goal through simple yes/no commands. This models the professor’s theory that an alien intelligence could have guided evolution.

Pascal will twist the facets of the cube under Eva’s hints. Godard makes this a tactile, even erotic exchange, with the close-up of her by his ear and Eva saying, “Yes,” more urgently as Pascal’s hands arrive at a solution, in the close-up surmounting this blog entry.

The next two shots of the sequence center on the prof, who has exited frame right from the “three-shot.” Now he’s at the window, recalling the initial shot of Eva; but unlike her he’s little more than a silhouette. As crashing organ music is heard, he seems to be watching the experiment from afar. The second shot, an axial cut-in, coincides with the offscreen voice of a male student: “Were you exiled for these ideas?”

“These ideas, and others,” the prof replies. He says he’ll see the class on Monday, evoking the idea that he’s dismissing the offscreen students, and he turns his head slightly, though we can’t be sure they’re on his right. This shot will be held for some time as students quiz him more about his theory, and Eva asks him if he’d like to come over for a drink some evening. But we don’t see her say it. Godard cuts to a shot of Eva at the window, bathed in sunlight, opening and shutting her eyes as she slightly lifts and lowers her head.

As we see her, we hear the rustling of people leaving (so the class was evidently larger than three). And we hear him reply to her invitation, “That’s another story [scénario].” Are Eva and the prof looking at each other? We’re inclined to say yes, but her closed eyes and tilting head suggests someone lost in contemplation rather than engaged in conversation. Here the classic facial-expression cue is made indeterminate. We have no way of knowing if the prof’s line comes from offscreen, or is displaced from another point in time; maybe he has left the room. Such displaced diegetic sound occurs elsewhere in the film.

We don’t have to decide; our indecision is the point. By pruning away the most reliable cues, Godard wins both ways. We’re kept somewhat oriented to an intelligible action: a prof sets forth his far-fetched theory of human origins and a woman in his class invites him for coffee. This side of the balance allows us to feel that a story, however sketchy, is moving forward.

But the moment-by-moment texture of the scene allows the individual shots, gestures, and sounds to drift somewhat free. Each image takes on a more intrinsic weight, and the juxtaposition of picture and sound acquires a resonance that we usually call poetic. A shot of Eva in the sun playing with the Rubik’s cube, unanchored in time (during class? before class started?), invites us to apply metaphors, especially once we learn her name. Pascal’s thorny hair suggests not only extraterrestrials but the explosion of a nova. The silhouetted prof, detached from the mechanism he has set in motion, hints at an unknown deity watching the game play out according to his rules. Why do Godard films spawn long essays built out of erudite associations? Because the narrative progression relaxes and we can weave our own connotations out of what we see and hear.

If you don’t want to go down the expanding-association route, there’s another one open. When individual moments no longer accumulate ordinary dramatic pressure, we can savor the fugitive pleasures of the separate shots (light on face, lips by ear) and the patterns they form: flipover cuts, yellow hair and yellow facets, bookended shots of Eva at the window.

Those patterns, it should be clear, depend on our sensing a bump at every shot change, looking for a way to skip across the gap that Godard creates. The same belief that meaning and effect are born of gaps impelled Kuleshov too, and perhaps even Lloyd. If we pay attention to those gaps we can feel minds—both the filmmaker’s and ours—at work in them.

(1) Lev Kuleshov, “’50’: In Maloi Gznezdinokovsky Lane,” Kuleshov on Film, trans. and ed, Ronald Levaco (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1974), 200.

(2) V. I. Pudovkin, “The Naturschchik instead of the Actor,” Selected Essays, ed. and trans. Richard Taylor (Oxford: Seagull, 2006), 160.

(3) See Kristin Thompson, Yuri Tsivian, and Ekaterina Khokhlova, “The Rediscovery of a Kuleshov Experiment: A Dossier,” Film History 8, 3 (1996), 357-367.

(4) The sequence does begin with a long shot of the café, but it is so distant, crowded, and brief that it can’t really be said to establish the spatial relationships among the several characters we see.

(5) “Sounds of Silence,” Artforum International (April 2000): 123.