Archive for the 'Directors: Jia Zhang-ke' Category

Once upon some times in Hong Kong

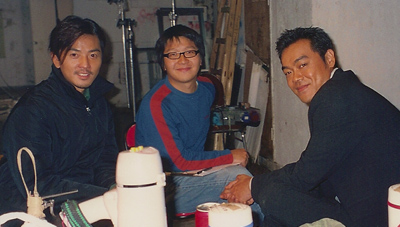

Johnnie To Kei-fung on the set of Running out of Time 2.

DB here:

Exactly nine years ago, Kristin and I were in Hong Kong. Lau Shing-hon, head of the film division of the Academy for Performing Arts, had arranged for me to be Sir Edwin Youde Memorial Fund Visiting Professor. It was a great honor, and Kristin and I enjoyed many happy sessions with Shing-hon, his colleagues, and his students. On this trip, though, something else happened. That lucky encounter has had consequences for my thinking about cinema throughout all the years since.

The encounter was the result of unintended networking. Jeff Smith, now a professor here at Madison, had been my TA in the early 1990s, when I was starting to include Hong Kong films in my courses. He caught the bug. While Jeff was teaching at NYU, a young Taiwanese man, Shan Ding, took some of his courses. Shan, who was naturally as keen on Hong Kong cinema as we were, wound up going to Hong Kong and eventually getting a job with Johnnie To Kei-fung.

So it was during our November 2001 stay that I got a call from a friend, who said that Shan was trying to reach me. Shan wanted to get together, but not in the customary coffee shop or noodle restaurant. He invited Kristin and me to come to a set.

Local heroes

Lifeline.

While doing research for my book Planet Hong Kong in 1996 and 1997, I managed to interview several directors, screenwriters, cinematographers, and action choreographers. Johnnie To was on my list of people to meet because of the cult classics The Big Heat (1988), Heroic Trio (1993), The Executioners (1993), and Loving You (1995). There was also his prestige picture, All about Ah-Long (1989) and an extraordinary movie I saw during one trip to Hong Kong, the firefighter drama Lifeline (1997). At about this time Mr. To was launching his own production company, Milkyway Image.

I keenly wanted to talk with Mr. To, but for various reasons it didn’t prove possible. I submitted my manuscript to the publisher in mid-1998, so I couldn’t incorporate discussion of the three Milkyway masterpieces of that year: Expect the Unexpected, The Longest Nite, and A Hero Never Dies. By the time the book came out in early 2000, there had been three more: Where a Good Man Goes (1999), Running Out of Time (1999), and possibly To’s finest work, The Mission (1999). There I was: the most important director of the late 1990s and early 2000s was largely left out of my book.

Ironically, soon after PHK came out, Wong Kar-wai’s In the Mood for Love and Ang Lee’s Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon triumphed at Cannes. Westerners’ perception of Chinese film changed forever. But in all this fuss, where was Johnnie To?

Making movies, that’s where. He emerged as a heroic figure of local film of the 2000s. True, Infernal Affairs (2002) and Stephen Chow Sing-chi and Wong Kar-wai sustained interest in Hong Kong movies on the international market. But Wong and Chow made films at long intervals, while IA was that rarity in Hong Kong, a “must-see” movie not starring Chow, Jet Li, or Jackie Chan. Johnnie To was just moving ahead, creating romantic comedies, cop dramas, and unclassifiable items like Running on Karma (2003) and Throw Down (2004). Election (2005) and Election 2 (2006) showed, in unprecedented detail, how triad societies governed themselves, and more daringly how they were still connected to mainland China. With his longtime collaborator Wai Ka-fai he went out on a limb with Mad Detective (2007), but on his own he gave us satisfying polars like Exiled (2006) and Triangle (2007) as well as lighter exercises like Sparrow (2008).

Unlike the reclusive Wong Kar-wai and Stephen Chow, To stepped into the public eye. He tried to sustain the local industry by hectoring the government, throwing his weight behind new awards, supporting student film contests. He worried, he has explained, that filmmaking in Hong Kong could collapse the way it did in Taiwan. And he kept surprising us—not least by signing arthouse demigod Jia Zhang-ke to make, of all things, a martial arts movie.

Most of those developments were in the future when we got the call from Shan.

One rainy street

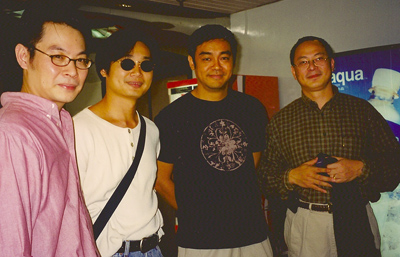

Johnnie To and Shan Ding, Milkyway Image office, 2005.

A van picked us up on a rainy night and we drove far into the New Territories. Along the way Shan was explaining that he was a sort of man-of-all-work for Mr. To. I would see over the years that Shan would assist in scripting and shooting, he might step in front of the camera, and he would help execute ad campaigns. He was sometimes billed as a film’s “Production Supervisor,” which is probably as good a description as any. Because he has fluent English, he was the ideal liaison between Milkyway and the west. Shan played a central role in helping critics and festival programmers learn about Milkyway’s projects.

We arrived at a big abandoned storage facility in a grove of trees. A street set about a block long had been built, bathed in artificial rain and mist. Mr. To was presiding over things.

He greeted us warmly. I had met him briefly at a 1999 Hong Kong film festival event arranged by Athena Tsui and Li Cheuk-to. The festival’s Panorama section paid tribute to Milkyway’s big films of the previous year, and a seminar was held with Wai Ka-fai, Patrick Yau Tat-chi, Lau Ching-wan, and Mr. To.

But by then Planet Hong Kong was in press. Nonetheless, I came to the seminar and took notes. I hoped that some day I would write about this team’s remarkable movies.

That November night Mr. To graciously said he remembered me from the seminar. But he soon went back to work as the crew prepared for what would be a bicycle race. A bicycle race? Who’d be racing? Kristin and I turned, and I gaped. There was Lau Ching-wan.

What Chow Yun-fat was to John Woo, Lau was to To: his exemplary protagonist. Chow was virtually born in a tuxedo, but onscreen Lau projects the image of an ordinary working stiff. In To’s films he usually plays the profane, irritable, unheroic hero; or if the film has no hero, as in The Longest Nite, he becomes a glowering, implacable force.

Not tonight, though. He was as friendly as Mr. To. His English was fine and we chatted a little. For the life of me I can’t recall what we said; I was too, as the Brits say, gobsmacked. I have long known I was a fanboy at heart, but here was the embarrassing proof.

Standing next to him was Ekin Cheng Yee-kin–at that point, one of the leading jeunes premiers of Hong Kong film. He had made his career as a teen idol, particularly in the young-triads cycle known in English as the Young and Dangerous series. He was also extremely cordial.

Both actors had to do a lot of waiting around between shots, of course. While we snacked on food from Styrofoam containers, there was time for pictures. Here’s one of Lau and Cheng flanking Yau Nai-hoi, Mr. To’s prolific screenwriter and later director of Eye in the Sky (2007).

We couldn’t get too close to the main set, but I did get some general shots of the crew at work. The crew filmed take after take of Lau and Cheng pedaling along the same short strip, over and over. I also got some shots of the stunt men, who were trying again and again to knock off some cars’ side mirrors. These guys take some serious spills.

Only when I saw Running Out of Time 2 was it clear that our night’s shoot, and others before and after, yielded a charming scene in which Ekin, the unnamed magician figure, taunts and exasperates Lau as detective Ho. It’s crucial because the race teaches Ho that Ekin’s mysterious cat-and-mouse game is essentially benevolent, even joyful. Staring at the set, I was impressed by how fake it looked. But on film, swathed in darkness, rain, and mist, it looks fine.

Yesterday, re-watching the movie, I enjoyed spotting the moment when we pass from the location to the set. From a shot taken on location, To cuts to a tighter shot of Lau, on the set.

Track in to Lau’s face as we hear a bike bell and Ekin whizzes by.

At Ekin’s urging, Lau grabs a bike and pursues him.

Once you see the film, you can notice how most of the shots are framed to conceal the fact that Lau and Ekin are pedaling down the same stretch over and over, sometimes in reverse directions on the set. Occasionally a changed background sign gives away the repeated takes.

Elaborate as this is set was, it’s still more economical in Hong Kong to mount such a thing than to spend nights on location to get dozens of shots. The magic of the movies, after all. And the signs enable product placement to help cover costs.

Never a man to waste a chance, Mr. To re-dresses the set a bit for Running Out of Time 2‘s cheery epilogue, when Christmas breaks out.

Just as in classical Hollywood cinema, scenes echo one another partly because it’s economical to re-use sets at different points in the movie.

This wasn’t my last encounter with Johnnie To. Shan kept in touch, and my spring visits to Hong Kong included a stopover at Milkyway headquarters. There I would run into Lorenzo Codelli, Shelly Kraicer, Todd Brown of Twitchfilm, Sabrina Baracetti of Udine’s Far East Film Fest, Grady Hendix of the New York Asian Film Festival, and other movers and shakers in film culture. Partly because of To’s promotional outreach to these tastemakers, he is much better known worldwide than he was in 2001. I managed to visit shoots for Throw Down, Exiled, and Triangle. He showed me work-in-progress versions of several films. Mr. To also sat down for interviews with me; my favorite is the one in which he went shot by shot through the “Sukiyaki” scene in A Hero Never Dies. Needless to say, I learned a lot from all these encounters.

These days I’m refurbishing my book for web publication, writing frantically while listening to Cantopop (Sammi and Faye and Gor Gor, mostly). Now I can give Milkyway its due. I’ve spent the last couple of weeks reviewing To’s oeuvre, and I’m more convinced than ever that he is one of the finest directors of the last fifteen years. Planet Hong Kong Redux will contain two lengthy sections on his films. Like all the illustrations in the new version, the stills (many from 35mm prints, not DVDs) will be in color.

As PHK Redux moves closer to online publication in mid-December, I’m mounting other items for the delectation of those discerning souls who know that Hong Kong has created one of the great traditions of film history. This week the site adds my DVD booklet essay on Mad Detective, courtesy Nick Wrigley and Masters of Cinema. And in a couple of weeks, as a run-up to PHK Redux, we’ll be putting up a gallery of celebrity snapshots I’ve taken since my first visit to Hong Kong in 1995.

Secrets

Oh, yes, what were the consequences of this evening in November 2001? Well, one was meeting a new batch of interesting people, Shan and Mr. To and Mrs. To and Martin Chappell and others. Their warm, informal hospitality constitutes one reason I come to Hong Kong every spring.

Another consequence: the conviction that I would have to write more about Hong Kong film. Having followed it since the 1970s, I thought I detected a dropoff in quality and energy in the late 90s. I wasn’t alone. The revised version of my book details how the industry went into a slump then. But the movies from Milkyway showed that you could still flourish in hard times. Seeing Mr. To’s movies made me want to stick with this tradition a little longer. So I continued to write, mostly short pieces about him, until PHK’s going out of print pushed me to update my thinking.

A third consequence of that set visit was broader and deeper. Getting to know filmmakers confirmed that I was a fanboy through and through, but I also felt it shifted me in new directions as a researcher. I’m fascinated by the practice of making movies. I still want to know, within my limited technical expertise, the tangible stuff that people do to build the images and sounds that captivate us. What tools do they use? What work routines have become standardized? What happens when technology or craft practices change?

As a graduate student, I thought that in order to understand movies we just needed to look at the screen. Although I had made some amateur films (bad ones), I failed to see that the fine grain of craft is exactly where artistry begins. By the time I started to write academic essays and books, especially The Classical Hollywood Cinema, I realized that knowing what goes on behind the screen sensitizes you to what’s there. You literally see more.

Most film academics aren’t interested in how craft can nourish artistry. In their eagerness to avoid “formalism,” they tend to neglect artistic traditions, trends, and choices. Movies are made, and the making—poeisis, as the old Greeks called it—demands concrete decisions about form and style. Filmmakers make different choices in different times and places, and we can try to analyze and explain some of those choices. As E. H. Gombrich once suggested, very simply, the artist’s key question is often: “What is there for me to do?” We need not stop there, but considering creative options and decisions is a good place to start if you want to do justice to the films, the filmmakers’ hard work, and the experiences we have as viewers.

I want to know directors’ secrets, especially the ones they don’t know they know. Planet Hong Kong was an effort to bring some of those secrets to light. I think I’ve found some more since then. Thanks to the courtesy of filmmakers like Mr. To, I’m compelled to try sharing them with you.

A fairly recent interview with Johnnie To is here. Especially interesting are his memories of growing up in Kowloon Walled City, a sort of criminal jungle. Corpses on the playground, that sort of thing.

Although the book will pay tribute to them, let me here signal two excellent online resources, now far more elaborated than when I wrote the first version of the book. Ryan Law’s Hong Kong Movie Database is indispensible for investigating people, companies, and films (detailed lists of cast and crew members). HKMDB also has a lively news section. Ross Chen’s vast and entertaining LoveHKFilm lives up to its name, with meaty reviews and news updates. There are many other fine sites, but these are the ones I’ve relied on most often. In addition, I must signal a book that came out too late for me to use; John Charles’ remarkable Hong Kong Filmography 1977-1997.

The friend whom Shan contacted was Li Cheuk-to. Since 1995 Ah-to has been my advisor, translator, editor, and host. I owe him more than I can say.

I have many other people to thank for my times in Hong Kong, and the revised PHK will do so. In the meantime, if you’re interested in Johnnie To and Milkyway, you can check my other blog entries here.

P.S. After I finished this entry there came the sad news of the death of Mr. Wong Tin-lam, a director from the classic era of Cantonese cinema. His Wild, Wild Rose (1960) is still remembered as a trail-blazer. The father of director Wong Jing, he brought a grassroots gravitas to some of the best Milkyway films, in which he was likely to play a Triad elder. Go here for more pictures and background information.

Wong Tin-lam in A Hero Never Dies.

P.P.S., 20 November: Thanks to Yvonne Teh for correcting my spelling! Check her enjoyable Hong Kong site Webs of Significance.

The Dragons & Tigers’ late-night roar

Thomas Mao.

DB here:

First, the news flash: Tonight was the awards ceremony for the Dragons & Tigers competition for young filmmakers here at Vancouver. A jury doesn’t get more distinguished: it consisted of (left to right) Jia Zhang-ke, Denis Côté, and Bong Joon-ho.

They awarded two special mentions, one to Phan Dang Di’s Don’t Be Afraid, Bi! (from Vietnam) and to Xu Ruotang’s Rumination (China). On the last-named, check the still at the end of this entry.

The grand prize went to the Japanese film Good Morning to the World!, by Hirohara Satoru.

More details here. Congratulations to the winners!

Beginners’ luck

My Film and My Story.

Vancouver is unusually hospitable to shorts and features by newcomers. Two of this year’s D & T offerings illustrate how talent, unlike youth, is not wasted on the young.

A cinémathèque featuring classic films is about to reopen, and the manager has hired some twentysomethings to help her get things into shape. The result a network narrative: romantic rivalries, coming-of-sexual-age crises, the race to set up the screening space, and even a ghost story are woven together as the big day approaches. The film is split into eight chapters, each given an emblematic movie title. Two petty thieves interview for a job under the aegis of “Stranger than Paradise,” and an apparent love triangle is christened “Jules and Jim.” The cinephilia shapes the plots too, as when one boy gets the courage to kiss another after watching Happy Together.

My Film and My Story was a group project of students at the Art and Design School of Konkuk University in Seoul. Their professor proposed that each student write a script about the opening of the cinematheque, and the results were integrated into a single feature-length story. There were seven student directors, one per episode; a producer contributed an extra chapter. Most directors were on the set all the time, making suggestions and trying to fit bits together. (“We fought a lot.”) The remarkable visual consistency—smooth cutting, tight framing, and well-modulated lighting—came from the single director of photography. As the title suggests, some of the tales are based on incidents in the lives of its makers.

The film, presented in Vancouver by two of the directors, Hong Youjin and Kim Taeho, is a lively charmer, with plenty of comedy and pathos. The characters are quickly introduced, and there are nice touches of movie-nut satire. One girl with big spectacles saves all her ticket stubs, takes notes on every movie (I can identify), and is annoyed when a boy drapes his leg over the seat in front of him. The episodes make tactful use of digital techniques, particularly in one shot that fuses past and present through the classic color/ black-and-white disparity.

My Film and My Story wasn’t in the official young-film competition, but Icarus Under the Sun was. For once the ragged style of handheld video justifies itself in a tale of a girl who quits school and heads for Tokyo to work in a seedy mahjong parlor. Haruo rooms with a flighty roommate and her boyfriend, but becomes more attached to the workers in the parlor and the owner, a nearly blind, taciturn man for whom she conceives an almost daughterly affection.

The plot barely rises above anecdote, but it’s continually engaging through its focus on the performance of Abe Saori, one of the two directors. Haruo explains that she is “addicted to walking,” and some of the best scenes involve conversations during late-night wanderings in the bitter cold.

Starting out fairly choppy, the narration accumulates weight and breadth as Haruo becomes engaged in her work. The shots throughout are held rather long, but about halfway through, the scenes start to be built out of exceptionally long takes. When another worker, the boy Aran, takes sick, Haruo calls on him and we get an almost suspenseful treatment of her arrival in his apartment, with him lying almost motionless in a heap in the foreground.

The shot lasts almost four minutes as she comes forward to talk with him. Their subsequent conversation is filmed in a tight, leisurely shot as they eat burgers and explain their backgrounds—virtually the only exposition we get about Haruo’s troubled past.

The dingy look of many scenes carries a documentary conviction that a more polished work would not. And the rough texture is actually the product of patient care. Abe and her codirector Takahashi Nazuki explained that they spent ten months in shooting and two to three months in editing. But it’s no mere technical exercise either, since Abe calls it both a fictional film and a documentary about her experiences. Like her protagonist she spurned conventional schooling and went to Tokyo to live on her own. Rooming with Takahashi, she decided to make the film “to know certain shadows” in her life. Icarus Under the Sun is actually the duo’s second film, and they have already finished a third, the more technically slick Soft-Boiled Egg (Hanjuku tamago.). Another thing about young directors: They have energy.

Expecting

Takashi Miike’s 13 Assassins is not what you might expect. Unlike your typical Miike item, this one throws no curves. It is an old-fashioned, butt-stomping, gut-slashing swordplay movie, with swagger to spare. Adapted from a 1963 film, it’s Seven Samurai plus six, with explosives.

True, there’s a Miike signature moment early on that shows what Lord Noritsugu has done to a woman’s body in his quest for piquant entertainment. But this horrifying scene serves a very traditional purpose: To prove to swordmaster Shinzaemon Shimada (and us) that Noritsugu has failed his duty as a leader and must be assassinated. He isn’t merely brutal. He lives an aesthetic of exquisite savagery. He has turned droit de seigneur into performance art. A massacre, he says with a fetching smile, is fun. He is a handsome monster. We can hardly wait to watch him die—preferably like a dog, in the mud, in agony.

Thereafter all that we want from a chambara flows forth in abundance. Unsurprisingly, the plot is framed by the man-out-of-time motif. Noritsugu’s depraved tastes show that the samurai tradition and the Shogunate government have become decadent. This might be a warrior’s last chance to die nobly—but for what? What deserves a man’s loyalty? Hard times have convinced Shinzaemon that the samurai class must ultimately serve the people. But his old rival Hanbei, Noritsugu’s right-hand man, clings to the notion that the samurai serves his master, unswervingly. Hanbei goes to his death committed to traditional duty. But his commitment is proved unworthy when his lord has a little fun with his severed head.

Miike faced a choice. He could have provided each warrior a vivid backstory, differentiating and humanizing each one as Kurosawa did. Instead, given a two-hour running time, he concentrates on strategy: How can a baker’s dozen of fighters defeat Noritsugu’s troops, which will eventually swell to 200? The solution is to maneuver Noritsugu’s men into a village filled with traps that will give the assassins some advantages—surprise, rooftop ambushes, and a deployment of livestock as ordnance. Things are enlivened by a feral hunter, mocking the samurai code while wielding a mean slingshot. After supplying a sketch of each of the thirteen assassins, Miike spends his energy on action. The muddy, gory battle at the climax lasts forty-plus minutes, and is worth every penny of your admission. Magnet, the genre arm of Magnolia, has picked up 13 Assassins for early 2011 release, and you should start thanking them already.

If Miike surprises by doing something normal, Zhu Wen’s Thomas Mao really does keep you guessing. It’s a pleasure to see a movie in which you can’t imagine what will come next.

At first, things seem to go by the numbers. To a remote Chinese farm comes the artist Thomas, to stay a short while and do some drawing. His wizened host Mao provides bed (after the geese are shooed out) and board (mostly corn on the cob). The trouble is that Thomas speaks no Chinese and Mao speaks no English. Every interchange is a pas de deux of misunderstanding. Thomas generously gives Mao some money. Mao refuses—not, as Thomas thinks, because he’s too proud but because Mao considers the amount insultingly small.

So we seem to have the small-scale cross-cultural comedy, making amusing points about people’s petty differences. Then the ghosts arrive.

At least, they might be ghosts. A phantom swordsman and swordswoman float around Mao’s farm and do battle, ultimately slashing off each other’s arms before disappearing, never to return.

There are aliens too, invading Mao’s cabin with pop-concert glow sticks. They’re totally unexpected, like the warriors, and their visit is even more transitory.

Eventually Thomas leaves, and the film starts over. The second part offers a sort of crazy-mirror image of what we’ve seen so far. Artist becomes model, model becomes artist, dog becomes Doggy. If you like the double-track story of Syndromes and a Century, you’ll probably like Thomas Mao, which is less rigorous but more funny. (The very title is part of the joke.) Zhu, who has reveled in comic byplay in Seafood and South of the Clouds, gives us that rare thing, a movie that is whimsical without being precious. You learn about contemporary Chinese painting in the bargain.

More whimsy, also not overbearing: When Liu Jiayin told me last spring that she was making a movie about a plastic fish, I didn’t know what to expect. The answer comes in the short film 607. Here the ballet of family hands seen in Liu’s Oxhide II becomes more playful. 607 is part of a promotional series of shorts by independent filmmakers, and it’s sponsored by a Beijing hotel, The Opposite House.

Mr. Fish, wielded by Liu’s father, swims around the tub, occasionally flirting with a mushroom provided by her mother. Eventually Mr. Fish is tempted by a hook (the curled finger of Liu herself). Will he fall for it? In all, you have to admire the coordination of three people shifting smoothly offscreen around the tub, each person’s hands sliding out of one part of the frame and popping in somewhere else—somewhere, I need hardly say, fairly unexpected.

PS 9 October: This entry has been corrected from its initial appearance. There I had written that Liu Jiayin’s 607 is one of three films she is making for the series commissioned by The Opposite House. Actually, the entire series consists of three films made by independent filmmakers. 607 is one of those and is complete in itself. Thanks to Shelly Kraicer for the correction.

Rumination.

More light from the East

Useless (Jia Zhang-ke, China, 2007).

DB’s last communiqué from the 2007 Vancouver International Film Festival:

I’m so taken with José Luis Guerin’s En la ciudad de Sylvia (Spain/ France) that I’ll be devoting a separate blog entry to it soon. At Vancouver it was projected with his Unas fotos en la ciudad del Sylvia, a remarkable sketchpad for and rumination on the feature. Rubbed together, the two films throw off sparks. En la ciudad is in color and very tightly constructed, Unas fotos consists of hundreds of black-and-white stills linked by associations and intertitles, with no sound accompaniment. Guerin, an admirer of Murnau, says that as a young man he watched old films in “a sacred silence” and he wanted to try something similar.

Unas fotos may not be factual—call it a lyrical documentary—but it illuminates En la ciudad in striking ways and is intriguing in its own right. Structured as a quest for a woman the narrator met 22 years ago, the film moves across several cities and invokes as its patrons Dante and Petrarch, each of whom yearned for an unattainable woman. But this isn’t exactly a photo-film à la Marker’s La jetée; it uses dissolves, superimpositions, and staggered phases of action to suggest movement. The subjects? Dozens of women photographed in streets and trams. Some will find a creepy edge to the movie, but it didn’t strike me as the obsessions of a stalker. Guerin becomes sort of a paparazzo for non-celebs, capturing the many looks of ordinary women.

Watch this space for more on the many looks of Sylvia. For now, more Asian highlights from Vancouver.

Fujian Blue.

Johnnie To and Wai Ka-fai have reunited for The Mad Detective (Hong Kong), which is as off-balance as you’d expect from its premise. Evidently spun off those TV series that feature telepathic profilers, the film stars Lau Ching-wan as a detective who solves cases by intuiting crooks’ “inner personalities.” We’re introduced to him crawling into a suitcase and asking his partner to throw it downstairs. After a few bumpy descents, he flops out and names the man who packed up a girl’s body the same way. Soon Lau is mentally reenacting a convenience-store robbery, and To/Wai cut together various versions of it as he plays with the possibilities.

Years after Lau leaves the force, his partner brings him back as a consultant to another case. By now, though, our mentalist has gone mental. The filmmakers get comic mileage, and some genuine poignancy, out of intercutting his hallucinations with what’s really happening. Lau envisions multiple personalities within the man they’re hunting, and as he traces out clues each personality flares up. To and Wai carry their dotty premise to a vigorous climax that multiplies the mirror confusions of both Lady from Shanghai and The Longest Nite. The brilliant sound designer Martin Chappell is back on the Milkyway team, making the effects and music magnify Lau’s heroic disintegration.

Lee Chang-dong, of Peppermint Candy and Oasis, has won his widest acclaim yet with Secret Sunshine (Korea). As your basic domestic crime-thriller Born-Again-Christian female-trauma melodrama, it’s undeniably gripping.

Lee Chang-dong, of Peppermint Candy and Oasis, has won his widest acclaim yet with Secret Sunshine (Korea). As your basic domestic crime-thriller Born-Again-Christian female-trauma melodrama, it’s undeniably gripping.

Secret Sunshine earns its 130-minute length, because Lee needs time to do several things. He traces the assimilation of a widow and her little boy into a rural town. Then he must follow the remorseless playing out of a harrowing crime. He makes plausible her succumbing to fundamentalist Christianity and her growing conviction that she needs to forgive the criminal. And there are more changes to come.

For me the most unforgettable moment was the heroine’s appalled confrontation, in a prison visiting room, with the man who wronged her. His unexpected reaction dramatizes how religious faith can cultivate both emotional security and an almost invincible smugness. Jeon Do-yeon won the Best Actress award at Venice for her nuanced performance, and Song Kang-ho, best known for The Host and Memories of Murder, lightens the somber affair playing a man of indomitable cheerfulness and compassion.

I found Brillante Mendoza’s Slingshot (Philippines) quite absorbing. Hopping among various lives lived in the Mandaluyong slums, it’s shot run-and-gun style, but here the loose look seems justified by both production circumstances and aesthetic impact. It was filmed on actual locations across only 11 days, and though it feels improvised, Mendoza claims that it was fully scripted and the actors were rehearsed and their movements blocked. Most of the actors were professionals, intermixed with non-actors—a strategy that has paid off for decades, in Soviet montage films and Italian Neorealism. Slingshot reminded me of Los Olvidados, both in its unsentimental treatment of the poor and its political critique, the latter here carried by the ever-present campaign posters and vans threading through the scenes. I suspect that the final shot, showing an anonymous petty crime accompanied by a crowd singing “How Great Is Our God,” would have had Buñuel smiling.

I found Brillante Mendoza’s Slingshot (Philippines) quite absorbing. Hopping among various lives lived in the Mandaluyong slums, it’s shot run-and-gun style, but here the loose look seems justified by both production circumstances and aesthetic impact. It was filmed on actual locations across only 11 days, and though it feels improvised, Mendoza claims that it was fully scripted and the actors were rehearsed and their movements blocked. Most of the actors were professionals, intermixed with non-actors—a strategy that has paid off for decades, in Soviet montage films and Italian Neorealism. Slingshot reminded me of Los Olvidados, both in its unsentimental treatment of the poor and its political critique, the latter here carried by the ever-present campaign posters and vans threading through the scenes. I suspect that the final shot, showing an anonymous petty crime accompanied by a crowd singing “How Great Is Our God,” would have had Buñuel smiling.

Off to China for Fujian Blue by Robin Weng (Weng Shouming). The setting is the southeastern coast, a jumping-off point for illegal immigration. The plotline has two lightly connected strands. In one, a boys’ gang tries to blackmail straying wives by photographing them with boyfriends, going so far as to sneak in homes and catch the couples sleeping together. The other plot strand presents Dragon, a boy who’s trying to sneak out of China and make money overseas. The whole affair is reminiscent of Hou Hsiao-hsien’s Boys from Fengkuei, and in Dragon’s story we can spot overtones of Hou’s distant, dedramatized imagery. Yet Weng adds original touches as well, including an almost subliminal ghost of London across the blue skies of the China straits.

Fujian Blue shared the festival’s Dragons and Tigers Award with Mid-Afternoon Barks (China) by Zhang Yuedong. The two films are very different; if Weng echoes Hou, Zhang channels Tati and Iosseliani. (When I asked him if he knew the directors, he didn’t recognize the names.) Mid-Afternoon Barks is broken into three chapters. In the first, a shepherd abandons his flock and wanders into a village. An unknown man shoots pool. Dogs bark offscreen. The shepherd shares a room with another visitor, but midway through the night, the innkeeper orders them to put up a telegraph pole. When he awakes, the man is gone, and so is the pole. He wanders on.

Fujian Blue shared the festival’s Dragons and Tigers Award with Mid-Afternoon Barks (China) by Zhang Yuedong. The two films are very different; if Weng echoes Hou, Zhang channels Tati and Iosseliani. (When I asked him if he knew the directors, he didn’t recognize the names.) Mid-Afternoon Barks is broken into three chapters. In the first, a shepherd abandons his flock and wanders into a village. An unknown man shoots pool. Dogs bark offscreen. The shepherd shares a room with another visitor, but midway through the night, the innkeeper orders them to put up a telegraph pole. When he awakes, the man is gone, and so is the pole. He wanders on.

In the second episode . . . But why give away any more? In this relaxed, peculiar little film Beckett meets the Buñuel of The Milky Way and The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie. As the enigmatic men without pasts or even psychologies wound their way through the long shots, Zheng’s quietly comic incongruities won me over long before the last dog had barked and the last ball had bounced.

Jia Zhang-ke is known principally for fiction films like Platform, The World, and Still Life, but from the start of his career he has shown himself a gifted documentarist as well. His In Public (2001) is a subtle experiment in social observation, and Dong (2006) made an enlightening companion piece to Still Life. Useless is more conceptual and loosely structured than Dong. Omitting voice-overs, Useless offers a free fantasia on the theme of China as apparel-house to the world.

The first section of the film presents images of workers in Guangdong factories as they cut, sew, and package garments. Jia’s camera refuses the bumpiness of handheld coverage; it opts for glissando tracking shots along and around endless rows of people bent over machines. (Now that fiction films try to look more like documentaries, one way to innovate in documentaries may involve making them look as polished as fiction films.) Jia also gives us glimpses of workers breaking for lunch and visiting the infirmary for treatment.

In a second section, Useless follows the success of a fashion house called Exception, run by Ma Ke. Her new clothing line Inutile (Useless) consist of handmade coats and pants that are stiff and heavy, almost armor-like, and that flaunt their ties to work and nature. (Some outfits are buried for a while to season.) Ending this part with Ma’s Paris show, in which the models’ faces are daubed with blackface, Jia moves back to China and the industrial wasteland of Fenyang Shaoxi. There he concentrates on home-based spinning and sewing. Neighborhood tailors patch up people’s garments while the locals descend into the coalmines. A former tailor tells us that he gave up his work because large-scale clothes production rendered him useless.

Jia’s juxtaposition of three layers of the Chinese clothes business evokes major aspects of the country’s industry: mass production, efforts toward upmarket branding, and more traditional artisanal work. Without being didactic, he uses associational form to suggest critical contrasts. The miners’ sooty faces recall the Parisian models’ makeup, and their stiff workclothes hanging on a washline evoke the artificially distressed Inutile look. What, the film asks, is useless? Jia shows industrial China’s effort to move ahead on many fronts, while also forcefully reminding us of what is left behind.

Thanks to Alan Franey, PoChu AuYeung, Mark Peranson, and all their colleagues for a wonderful festival. They’re so relaxed and amiable, they make it look easy to mount 16 days crammed with movies. Be sure to check on CinemaScope, the vigorous and unpredictable magazine that makes its home in Vancouver. It gives you many gems online, but it’s well worth subscribing to.

Alan Franey, Director of the Vancouver International Film Festival; PoChu AuYeung, Program Manager; and Mark Peranson, Program Associate and Editor of Cinema Scope.

Movies that restore your faith in cinema, and audiences

David from Vancouver:

One of the pleasures of film festivals is the enthusiasm you pick up from the audiences. Queueing for a screening, you can talk with people about what they’ve seen or expect to see. This festival is so popular locally that some viewers take a week or two off work. Then sitting in the theatre and waiting for the show to start, you hear fascinating conversations. Last night, a young Taiwanese man (Frank) and a young Korean woman (Yuri) were sitting behind me and talked about what they were looking forward to, what they’d seen on DVD, how they came to Canada, and so on. Their love of cinema shone through plainly; somebody should make a movie about their lives.

People have every reason to be fired up about this festival. After five days here, I’m awash in fine movies. Besides the ones I’ve already noted, here are some standouts:

Opera Jawa: An ambitious reworking of an episode from the Ramayana, full of splendid imagery—everything from elaborate dance numbers to sudden appearances of shadow puppets. The soundtrack is equally lush, with gamelan mixing with more pop-flavored melodies, and the classic tale is intercut with current political struggles.

Monkey Warfare: A clear-eyed study of baby boomers stuck in late midlife, recalling their 1960s activism with both pride and guilt. It’s tough to make a movie with only three principal characters, but Reg Harkema pulls it off, blending comedy and drama and throwing in enough neo-Godardian flourishes to keep you off-balance. A very funny post-credits sequence. (But don’t Molotov cocktails also contain sand?)

The Magic Mirror: I tend to like about half of Manoel de Oliveira’s works, and I thought during the first forty-five minutes that this wouldn’t be one of them. Of course everything was filmed with his quiet majesty. (Advocates of the “clean image” furnished by HD should study what O’s films can squeeze out of Eastman stock: his etched, enameled images make every texture pop out at you.) But the early scenes feature rather repetitive dialogues about a wealthy woman who hopes to be granted a vision of the Virgin. I couldn’t see where all this was going and suspected that I was in the presence of what my friend J. J. Murphy, borrowing from Manny Farber, calls elephant art.

So I was squirming until a forger enters the scene with a plan to stage a vision for Mme Elfreda. Things get stranger and more elliptical, moving toward luminous glimpses of her final journey to Venice and Jerusalem. By the end I was completely won over by this grave, wise film. Now I have to go back and watch the beginning to see what I missed. You have to take these things on trust, especially from a director who’s lived nearly a hundred years.

Big Bang Love—Juvenile A: I’m not a big admirer of Miike Takeshi’s films, but I liked this better than most. Very stylized treatment of a young bully’s death in prison, with startling images and passages of brilliant cutting, and a landscape that haunts you. (Let’s just mention the pyramids and the rocket ship.)

Syndromes and a Century: A teasing, mesmerizing string of situations involving two doctors in a Thai hospital. Shot largely in long, distant takes, the film works out variations in its conversations among doctors, patients (including two Buddhist monks) and their lovers. Plot lines are sketched without being consummated, and the viewer is coaxed into imagining different futures for the people who drift into our ken. Apichatpong Weerasethakul, maker of Mysterious Object at Noon and Tropical Malady, has emerged as the major Thai director with his enigmatic and engrossing films. For those of you in the Midwest, take pride: He studied at the Film School of Chicago’s Art Institute.

Still Life: Jia Zhangke’s newest feature, crowned at Venice, has immediately become my favorite of his works. The city of Fengjie, being slowly demolished before it will be flooded by the immense Three Gorges Dam, becomes as vivid a presence as the theme park in The World. Day laborers take shelter in collapsing buildings, and prostitutes ply their trade in rooms with only three walls. One worker has come to town looking for his ex-wife; a woman has come from Shanghai seeking to divorce her husband.

The parallels aren’t forced, and the two stories are integrated by one of the most daring visual surprises I’ve seen in recent cinema. The stories are intimate, built out of small-scale encounters and daily routines, but they feel oddly epic too, as the hollowed-out city crumbles around the characters. In fewer than two hundred shots, many of them gliding along surfaces and faces, Jia presents a vision of humans obstinately seeking a better life. Shot on HD and projected on video, Still Life proves that digital filmmaking can evoke both thumping immediacy and poetic abstraction. (Keep your eye on the backgrounds.) It’s been acquired for Canada: What stateside distributor will pick it up?