Archive for the 'Directors: Hitchcock' Category

Tell, don’t show

Exodus.

DB here:

Watching the film adaptation of Stieg Larsson’s Girl with the Dragon Tattoo reminded me how common fragmentary flashbacks have become. Granted, we’re living in a period of flashback frenzy, one comparable to the delirious 1940s and 1960s. But the format of the flashbacks has changed a bit. The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo, like many other films, gives us mere glimpses of earlier events–literally, flashes back to the past.

The technique is actually quite old. American films of the 1910s often interrupted present-time scenes to remind us of actions we’ve already seen or been told about. But the fragmentary flashback waned during the heyday of sound cinema. There conversations did nearly all the work. Of course there were flashbacks, as I’ve discussed in an earlier entry. But those flashbacks tended to be extended scenes, not the jagged bursts we get now.

A cynic might say that today’s audiences are so thick-headed and impatient that simply mentioning what happened earlier isn’t enough. Viewers now would chafe at the long interrogations in The Maltese Falcon and The Big Sleep. The scenes would need to be split up by images showing what the characters were explaining. The new rule: Add redundancy, but dress it up in whipcrack visuals.

So are the flurries of mini-flashbacks there just because filmmakers doubt that viewers can follow a twisty intrigue given in dialogue? Not necessarily. I suspect that these flourishes are traceable to a piece of current screenwriting advice. It’s usually formulated as Show, don’t tell.

The very distinction has some ancient ancestry. Plato and Aristotle both distinguished between verbal narration, as in the Homeric epics, and theatrical presentation. Aristotle, always more interested in craft than Plato, went on to point out that the distinction couldn’t be absolute. Epic narration could include simulated conversations, for example. Aristotle did not, so far as I can tell, urge composers of epics to avoid “showing” or dramatists to avoid having characters report offstage action.

Today’s bias in favor of “showing” is probably traceable to the emergence of the modern novel. “Dramatize, dramatize!” Henry James (a failed playwright) advised the novelist. That is, make the action on the page seem vivid and palpable. It was Joseph Conrad, not D. W. Griffith, who first claimed that his purpose was “to make you see.” A major trend in the theory of prose fiction ca. 1900 was the effort to turn words on the page into a surrogate for visual storytelling; hence the very term “point of view” and James’ comparison of unfolding narrative to a “corridor” that we traverse. It remained for Percy Lubbock, in The Craft of Fiction (1921) to sum up this trend. “A novel is a picture,” he claimed, and he suggested that novels, either “panoramic” ones like Vanity Fair or “dramatic” ones like The Awkward Age, can make us forget that they are actually verbal contraptions:

The art of fiction does not begin until the novelist thinks of his story as a matter to be shown, to be so exhibited that it will tell itself.

Screenplay manuals have picked up on the general advice, even while modifying it to suit the particularities of film. Novices are advised to reduce dialogue to the minimum. Even a novel committed to “showing” will rely on conversation, but in cinema long stretches of dialogue, and especially, God forbid, monologue are uncinematic and run the risk of boring the audience. Cinema, the reasoning goes, is a visual medium, and whenever you can replace a word, or a string of them, by images you should try to do so. The aim is what we now call visual storytelling.

Now I’m all for presenting the story through pictures. Show, don’t tell can challenge the screenwriter and director to get story points across through imagery and character behavior rather than expository dialogue. One mark of filmmaking skill is to guide the audience to make inferences rather than simply take in bald information.The question is: How far to go?

In their urge to picture every bit of action, contemporary filmmakers may be missing a chance to exploit another resource of cinema: the sustained scene in which a character talks about a past event without any visual supplement. A long verbal account of the past has unique virtues.

In other words: Filmmakers, consider telling and not showing what’s told.

Talking it through

In Persona, the nurse Alma has grown more intimate with her patient Elisabeth, a famous actress who has frozen on stage and now refuses to speak. During their time together, Elisabeth’s treatment becomes therapy for Alma. Compelled to fill the silences, she gradually reveals more about herself. Tonight, a little drunk, Alma confesses something shocking. Once, while her lover was away, she and a girlfriend had sex with a couple of young men. Her telling of it makes her more and more distraught, until she breaks down weeping in Elisabeth’s arms.

In this nearly seven-minute monologue, Alma describes the incident. She mentions a few details, such as the weather on the isolated beach and the blue ribbon on her straw hat. Mostly, though, she simply describes what happened, in laconic but vivid sentences. The result is an anecdote of absorbing eroticism. Lacking any images of the events, we get to imagine the scene of sexual exchange. Bergman releases us from what James once called “weak specificity”: perhaps no imagery this side of pornography could be as arousing as this bare-bones account.

But the fairly neutral words are given emotional coloration through Alma’s manner of telling. Her reaction mixes astonishment at the pleasure, guilt at betraying her lover, and shame in telling it to Elisabeth. By the end, she collapses into weeping confusion; the incident has made her doubt what sort of person she is. Here Bibi Andersson’s performance is crucial, with trembling sincerity giving way to anguish and self-reproach.

In sum, by presenting this monologue wholly in the present, Bergman gives us two layers of action simultaneously, a charged sex scene and its long-range emotional consequences. But there’s more. Had he given us flashbacks, he could not preserve the flow of the present-time action. The staging and cutting during Alma’s confession use simple film techniques, but they add another layer to the scene.

The master shot, seen above, gives us the two women as Alma begins her tale. Then straightforward analytical editing isolates each woman.

In a classic gesture of intensification, the next shots of Alma and Elisabeth are closer than the earlier ones. This pair of shots accompanies the highest point of what Alma is telling us—the first couplings.

The tight shot of Alma, in which she describes achieving orgasm, lasts almost two minutes and is the lengthiest shot in the sequence. Then the action pauses as Alma nervously curls over to grab a cigarette, goes toward a distant window to light it, then settles on the sill to resume her story.

The earlier close shot of Elisabeth had hidden her reaction behind her hand. Now she watches Alma in a sort of enjoyment. Friendly empathy or triumph at eliciting a damaging admission? It’s hard to say. Alma retreats to another window and turns away, as if responding to Elisabeth’s smile.

Alma finishes her tale by saying that that night, reunited with her lover, she had the most pleasurable sex of their relationship. Turning from the window, her face is angled in such a way that her confession seems at once indifferent to Elisabeth (the eyeline doesn’t seem angled toward the bed) and challenging to her: “Can you understand that?”

The next line of dialogue—“And I got pregnant of course”—introduces a rupture in the action’s space and time.

Now Alma is in bed with Elisabeth, as if her question had impelled her to the closest physical contact yet. As Alma twists in pathetic uncertainty, weeping, Elisabeth’s reaction is again initially suppressed (Alma’s arm blocks her patient’s eyes) before finally revealing Elizabeth’s face during the embrace. Yet the expression remains ambiguous—sympathetic, or victorious in having exposed her nurse’s inner life.

Later we will learn that Elisabeth’s caresses aren’t as affectionate as they might first appear. In any event, given the tenor of Alma’s revelation, it is hard not to see them as erotic gestures in the present, parallel to those Alma recounted.

By telling rather than showing, then, Bergman has been able to tell and show. Bergman lets Alma’s telling provide a sort of virtual flashback, while he also creates a ripening interchange between characters in the present. Instead of simply sandwiching fragments of the past into the present action, he has built up two smooth arcs of action, one that we imagine and one that is set before us in precise detail, with its own emotional modulation. The bliss of the past events is refracted through the pain of telling them.

Telling as therapy

Part of the rationale for telling rather than showing the beach orgy is, of course, the fact that much of it couldn’t be presented so literally on film; censors would object. More important is the fact that showing a heavy-breathing sexual encounter would be likely to undercut the developing revelation of Alma’s present feelings, the tension between the memory of uninhibited pleasure and the lingering shame and confusion.

The issue of what should be shown comes up in another classic scene of confession, the moment in Exodus when the Jewish teenager Dov Landau admits that he was an accomplice in running a concentration camp. Again the result is a tearful breakdown. Here, however, a conversational partner coaxes out the truth by quietly corrosive questions.

Dov is trying to join the Irgun, a guerrilla band seeking to drive the British out of Palestine. The senior officer, Akiva Ben Canaan, lets the cocky youth expand on his boast that he began fighting Nazis in the Warsaw ghetto but then was captured and sent to Auschwitz. At first Akiva probes gently. How did the camp officials decide who would live? And what did the Nazis do to the girls? Dov starts to shift uneasily. How was the killing accomplished?

Like Bergman, Preminger employs the standard method of providing closer views as the tension rises. Dov starts to relax as Akiva provides softball questions, but then he has to confess that the bodies were dumped in mass graves. Who dug the graves? Dov admits that demolition squads used dynamite to blow out trenches. Akiva induces him to admit that this was Dov’s job.

In the course of all this, Akiva moves around the room and leans closer to Dov, but the boy remains motionless in the same setup. The fixed framing accentuates his subtly changing expressions across the scene.

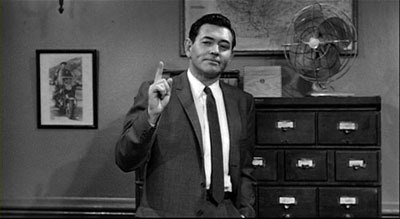

Akiva retells what Dov must have done: shave heads, collect bodies, harvest gold fillings. Dov crumples like a child under the admission (see the frame surmounting this entry), and like Alma at key points in her monologue hides his face in shame. “What could I do?”

What else has he to confess? Dov won’t say, until he collapses again: “They used me . . . like you use a woman.”

The distant framing here prepares for the scene’s final phase: the men rise and swear Dov into their group.

Today a filmmaker would be tempted to show at least some of what Dov tells us. We could get glimpses of life in the camp, along with subjectively distorted imagery of sexual abuse, perhaps from Dov’s point of view. But this could turn out to be James’ “weak specificity.” “Let the reader think the evil,” James advised. Accordingly, Preminger sticks obstinately to what Dov says and how Akiva’s softly voiced but damning interrogation brings out the truth.

Again, the scene’s power comes from the character’s emotional development during the telling. We can imagine the horrors that Dov faced as a boy, and our pity comes from empathizing with his changing expressions–bravado, ruffled concern, realization that he has been caught lying, revulsion at his betrayal and the sexual assault. That is, we sympathize through his response now, rather than through direct vision of what he encountered. We react to his reactions.

By the end, Dov seems dazed that his confession has been accepted. Partly this is surprise that he isn’t being rejected, but also it’s as if he has awakened from a dream–that of himself as a resistance hero. Akiva Ben Canaan forces him to confront what he had not faced. Once more, the confession becomes a talking cure.

As in Persona, the confession also characterizes the interlocutor. Akiva ‘s gentle manner fuses wisdom and severity, making him a quietly stern father confessor. He’s also a shrewd exponent of psychology, one who picks the moment of the boy’s greatest self-revulsion to declare that Dov is accepted into the Irgun. The confession has broken him; the Irgun will remake him. Having surrendered himself utterly he will prove a more loyal soldier than any recruit with an innocent past.

Again, the scene of telling has given us two continuous emotional arcs in two time frames, one concrete and one virtual: a past event we’re cued to imagine and a present stripping away of the teller’s defenses. People who complain that the dialogue scenes in Inglourious Basterds are overlong should consider the tradition of movies like Exodus and Persona.

Psycho babble

Persona and Exodus suggest two virtues of sustained recounting: arousing the viewer’s imagination, and providing an unbroken arc of present-time action that can generate sympathy through face, gesture, and voice. There’s one more advantage that isn’t perhaps so evident nowadays.

Current films give us “lying flashbacks” fairly often. But in the old days, with very few exceptions like courtroom films and tales like Rashomon, a flashback was veridical. In recounting a story action, a character might lie or make mistakes, but if the film’s narration showed us that action, we could trust that as the truth. As a result, many detective stories presented suspects’ versions of events through question and answer but climaxed in a flashback that showed us what really happened.

If, however, you want to induce doubt about what really happened, you might have the detective’s climactic explanation pricked by inconsistencies. This is what seems to me to be happening at the finale of Psycho. (Do I really have to warn about spoilers here?)

After Norman Bates has been captured, halted in another murder attempt, the psychiatrist Dr Richmond explains the young man’s split personality—part Norman, part Mrs. Bates, his mother. Richmond claims to have gotten the truth “from the mother.” At this point, he says, the Mom part of Norman has taken over wholly, a claim confirmed when we hear Norman speak in an old lady’s voice in the epilogue. Richmond goes on to claim that his questioning determined that Mother “killed the girl.” To get literal, it was as Mother that Norman murdered Marion Crane.

A contemporary film would very likely replay the murder so as to validate the psychiatrist’s analysis: Norman dressing up as his mother, assuming a cackling old-bat accent, killing Marion in images that fill in the silhouette that we saw in the shower sequence. We would see that Norman-as-Mother is the culprit.

But this visual confirmation of Richmond’s diagnosis would be made problematic by the epilogue that Hitchcock includes. In the final sequence we see Norman, staring out at the camera, and hear Mother’s voice declaring that her son committed the murders. According to her, Norman is the culprit; she wouldn’t hurt a fly. How then can Richmond declare that Mother told him that she killed the girl?

We might say that the doctor is extrapolating: the truth he took from the mother is that she is dissembling, shifting the guilt to Norman. But Richmond could have stated that was his reasoning, and he doesn’t. The incompatibility between his explanation and Mother’s soliloquy opens up the possibility that he has not probed to the depths of Norman’s madness.

Despite the fact that the psychiatrist’s analysis arrives at the moment when a conventional movie delivers the whole truth, the very last minutes of the film incline me to doubt Richmond’s ability to grasp the whole situation. It’s as if our parting vision of the character disturbs the smug certainties of the diagnosis.

I haven’t dived deeply into the Talmudic sea of Psycho commentary, so it’s likely that this issue has been hashed out extensively. Perhaps my construal won’t stand up. Take it, then, as a possible instance of the ways in which a verbal recounting, “unconfirmed” by a tangible flashback, can stand as only a candidate explanation rather than the whole truth. In general, telling and refusing to show can induce what Meir Sternberg calls “anticipatory caution,” a warning that the telling is only one, and not necessarily the most truthful, version of events.

Show, don’t tell is usually good advice. But I’m suggesting a codicil. Consider showing the telling. Fill it out. Pack it with actorly detail and psychological implication. Stage and shoot and cut it so as to create an engrossing, unfolding rhythm. That’s visual storytelling too, and it requires fine judgment. Who knows? More scenes relying on telling might also teach audiences to be a little patient.

The best modern account I know of the subtle differences between showing and telling, and the cases when the categories blur and fracture, can be found in Meir Sternberg’s Expositional Modes and Temporal Ordering in Fiction. I talk a little about the distinction in Chapter Two of Narration in the Fiction Film. See also The Way Hollywood Tells It for some comments on today’s vogue for unreliable flashbacks. And way back in 2006 Matt Zoller Seitz wrote a passionate attack on the idea of “Show, don’t tell” while defending the value of voice-over narration.

N. B. I’m not ignoring the possibility that film can present showing and telling in two simultaneous streams: imagery of the present situation accompanied, perhaps alongside, by continuing imagery of the past scene, as in Suddenly Last Summer. This can be a fruitful option, but it relieves the spectator of the obligation to imagine the past—an important advantage of the pure telling. There’s also the tricky matter of giving the two streams of information enough density. The past event needs to gain enough body to be more than a simple illustration, while the present-time telling could become merely a prop for the flashback. In the dual-presentation mode, the filmmaker risks dividing our attention and thinning the texture of each time frame, with the result that both lose vividness. That seems to me to happen in Suddenly Last Summer.

Psycho.

Robin Wood

DB here:

Robin Wood has just died. Kristin and I knew him a little; we recall a convivial dinner with Robin and Richard Lippe in New York during the 1970s. We knew him chiefly on the page, as a writer whom we valued enormously. I take this moment to acknowledge his death, to suggest his importance, and to praise his memory.

Today it’s hard to imagine the impact that Wood had on film criticism in the late 1960s and early 1970s. I first encountered his writing while I was in high school. I desperately wanted to know more about movies, but the nearest towns had no libraries. So I wrote to every film magazine I had heard of and said I was considering subscribing. Could they please send me a sample copy? The issues that came through included, most memorably, the Sarris “American Directors” issue of Film Culture and the Howard Hawks issue of Movie. Both changed me forever.

The Hawks issue contained Wood’s essay on Rio Bravo, a sort of draft for what would become one of his most important statements.

Hawks, like Shakespeare, is an artist earning his living in a popular, commercialized medium, producing work for the most diverse audiences in a wide variety of genres. Those who complain that he “compromises” by including “comic relief” and songs in Rio Bravo call to mind the eighteenth century critics who saw Shakespeare’s clowns as mere vulgar irrelevancies stuck in to please the “ignorant” masses. Had they been contemporaries of the first Elizabeth, they would doubtless have preferred Sir Philip Sydney (analogous evaluations are made quarterly in Sight and Sound). Hawks, like Shakespeare, uses his clowns and his songs for fundamentally serious purposes, integrating them in the thematic structure. His acceptance of the underlying conventions gives Rio Bravo, like Shakespeare’s plays, the timeless, universal quality of myth or fable.

Nearly every Wood virtue is already here. He takes it for granted that conventions are crucial to understanding and judging cinema. He refuses an evaluative split between high culture and popular culture. He insists that worthy films have serious thematic implications—in Rio Bravo, a link between self-respect and peer respect. He shows the film’s complexity through shrewd comparison (in the book on Hawks, High Noon will provide the telling contrast). And he gives the whole thing a polemical edge with the sideswipe at Sight and Sound, a target for many years to come.

But it was the books, in an apparently unending flow, that established Wood as a leading voice, and not only for me. I can’t convey the excitement that was ignited by Hitchcock’s Films (1965), Howard Hawks (1968), and Ingmar Bergman (1969), quickly followed by the monographs on Penn (1970) and Ray’s Apu Trilogy (1971). Nearly all books of film criticism were then simply collections of reviews. Wood’s stood as through-written, pondered over, carefully carpentered monographs, comparable to the best literary analysis. These studies showed, in incisive detail, what most auteur criticism simply proclaimed: great directors expressed their personal vision of life in and through cinema. Wood showed, scene by scene and sometimes shot by shot, that movies harbored layers of feeling and implication in their finest grain of detail. Without fanfare he introduced “close reading” to film criticism. Although never academic in the narrow sense, he took cinema as seriously as did critics of art or music or literature.

In fact, the word “serious,” a tonal center of the Rio Bravo essay, might be the keyword of his career. Partly that seriousness is intellectual. From the start Wood’s prose had a rectitude that was argumentative in the best sense. The Hitchcock book begins by imagining the best case one can make against the director; he then demolishes it piece by piece. The author does not try to woo us. He respects his reader enough to spell out his claims and to invite a skeptical reply. At last, we thought: An honest man.

The idea of seriousness took on a deeper import, one shaped by the indelible influence of F. R. Leavis. For Wood as for Leavis, great art inevitably grappled with the ultimate demands of living. Close analysis was nothing unless it revealed the author’s felt engagement with human values. This state of affairs imposed equally stringent obligations on the critic. Nothing could be farther from the snappy badinage and instant turnaround of Netwriting than Wood’s obstinate gravity. Flippancy and showing off had no place in serious criticism. Being a critic, analyzing and interpreting and judging, was a heavy responsibility, and every word had to be weighed. The very status of film as art, indeed the status of art itself, was at stake.

In a passage I cannot find on short notice, Wood once observed that a critic could not write “seriously” about Hou Hsiao-hsien’s Flowers of Shanghai after one viewing. Accordingly, not until he could study the film on DVD did he produce a characteristically penetrating essay. It’s a piece that anyone would be proud to sign, but Wood concludes:

I’m afraid the above analysis, in spelling things out, may have suggested that the film is more schematic than it actually is. Its “scheme” is in fact so subtly worked that it has taken me at least six complete viewings (together with more replays of individual scenes and moments than I can count) to disentangle it from all the detail of the realization. The above account is offered humbly, as a beginning.

This passion for nuance did not lead to a sort of scientific objectivity. The responsibility of criticism made writing inescapably personal. The critic responds to the work as a living being, as a “whole man alive”—a Leavis phrase that Wood was wont to quote. Personal Views, the title of Wood’s first collection of essays, signalled both the artistic visions expressed in the films he studied and the sincerity with which he advocated for or inveighed against a film, a trend, or a system of ideas.

I don’t know any critic whose intellectual and political horizons expanded as much as Wood’s did in the 1970s. Since criticism was for him a form of living, he took his readers along as he discovered structuralist theory (which he had once attacked), accepted some tenets of psychoanalytic theory, and launched ferocious attacks on patriarchy and capitalism. The same moral fervor that informed his 1960s writing became focused upon the political oppression of women, gays, the poor, and free thought. Now, he suggested, the apparent stability of “ordinary” life relied upon psychological and social repression. If one theme runs through his work—that of the precariousness of decent human relations in the face of disorder—it finds its late expression in his belief that conservative politics, in the name of maintaining order, is implacably bent upon destroying our kinship with others. In a sense, CineAction, the journal that he co-founded, was his latter-day Movie, a forum for his new commitment to criticism that promoted progressive social change.

The art he cared most about, I believe, laid bare the struggle between order and disorder. In his first book, he argues that Hitchcock shows comfortable “ordinary” people faced with a world coming to pieces. Across his career Wood ceaselessly questioned what exactly this normal order consists of. Coming out as a gay man, he devoted his finely meshed attention to reading films politically. Now those social forces that he once defined simply as threats to stability, such as the war in Bergman’s Shame, revealed themselves as products of warped political systems. The horror film presents disorder as a monstrous threat to bourgeois norms, yet it can become a powerful force in questioning those conceptions. For nearly four decades Wood recorded his efforts to grasp the concrete social implications behind the films he loved and those, increasingly from Hollywood, he found evasive and duplicitous. In all, complacent acceptance of the status quo was the enemy of the seriousness he prized. When he died he was at work on a study of Michael Haneke.

The seriousness of great artists, he came to believe, was inescapably political. Yet while this made him reevaluate Hawks and Hitchcock, it did not lead him to absolute repudiations. Always a believer in the validity of intuitive response, Wood would trust his sensibility more than the dictates of academic “frameworks” and theoretical systems. A 2004 set of notes on Ozu concludes:

These late Ozu films are detailed and highly intelligent critical studies in cultural change which ultimately defy the application of such terms as “progressive,” “regressive,” “conservative,” etc. . . . “Change” is not necessarily for the better (though our current culture is constantly telling us that of course it is) . . .—an obvious ploy of corporate capitalism, which depends upon the mystification for selling its products. If we gain new freedoms, we should also beware of casually casting off the past without asking ourselves what in it—what standards of seriousness, what beliefs, what aspects of our lives—might be worth preserving. I find all these thoughts in Ozu, incomparably expressed.

Through all the constant reappraisals of films, all the unsparing reconsiderations of his own judgments, one hears the same forthright, urgent voice. Leavis suggested that the good critic always asked, in effect, “This is so, isn’t it?” Wood’s writing consists of firm assertions accompanied by challenges to respond as an equal. The invitation is set out in an impassioned conversational cadence, complete with italics and appositional phrases. In search of clarity, Wood is prepared to argue and dissect forever; who else would produce not one but two books rethinking his defense of Hitchcock? Yet this brisk voice can also move us by its simplicity, as in the sentences concluding that little book on the Apu trilogy.

Suddenly the boy relaxes, and rushes forward into his father’s arms. The film ends with him seated on Apu’s shoulders as Apu walks away towards the future. In accepting the child, he has accepted life, has accepted the death of Aparna. Whether or not he is going back to become a great novelist is immaterial: he is going back to live.

Wood’s essay on Rio Bravo is in Movie no. 5 (undated, 1963?), 25-27. His “Flowers of Shanghai” appears in CineAction no. 56 (September 2001), 11-19. “Notes toward a Reading of Tokyo Twilight (Tokyo boshoku)” is in CineAction no. 63 (April 2004), 57-58.

For a wide-ranging and growing set of links to eulogies for Robin Wood, visit David Hudson at The Auteurs Daily and Catherine Grant at Film Studies for Free. A recent interview framed by enlightening commentary is Armen Svadjian’s 2006 tribute, “A Life in Film Criticism: Robin Wood at 75.” Wood’s 2008 list of the films he most valued is on the Criterion site here. D. K. Holm maintains an invaluable, continually updated bibliography of Wood’s writings here.

François Truffaut, Day for Night (1973).

Title wave

The very first drafts of the outline always had Cloverfield on them. . . . Cloverfield was what I always wanted to call the movie. . . . It’s a terrible title . . . if you’re trying to sell something, who the hell’s gonna go see that?. . . But it’s cool. There’s a reason. I could state the reason, but it’s very clear it is meant to be obtuse. I believe that the film answers why it is called Cloverfield, I believe that it’s in the film, I believe that you can make that argument. It says exactly what I want it to say. But it’s very clear that we don’t want to explain it.

Screenwriter Drew Goddard, at Creative Screenwriting podcast

DB here:

Don’t think about a movie title too long. Even a familiar one can turn strange before your eyes.

This was brought home to me long ago when I showed Lubitsch’s Lady Windermere’s Fan in a course. Before the film started, a student asked me, “Who is it?” I didn’t understand. “I mean, who is her fan?” It never occurred to me to take the title this way, but actually in the movie Lady W does attract a big fan.

Titles can be explicit, but they’re often metaphorical, associative, and oblique. Sometimes they’re downright obscure. But as Drew Goddard says, they can be cool.

Don’t Worry, We’ll Think of a Title (1966)

The least provocative titles are based on the protagonist’s name: Brubaker, Anthony Adverse, Erin Brockovich, Norma Rae, Speed Racer. One step removed is the title that describes the protagonist’s job or role: Gladiator, Hitman, The Cable Guy, Bob le flambeur, perhaps also The Godfather. Then there are the titles, like The Last Action Hero or Prince of Players or Little Caesar, that characterize the protagonist more figuratively.

If the movie has a pair of protagonists, the title can reflect that, as in David and Bathsheba, Pete’n’Tilly, and Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid. When the title elevates a secondary figure, as in Melvin and Howard or Harry and Tonto, it has the effect of making us consider the relationship between the two as central to the action. When there are several main characters, we can get a title characterizing the group, not just Bob & Carol & Ted & Alice but The Professionals and The Breakfast Club.

Things get a little more curious when the title focuses on a character other than the protagonist(s). Rebecca identifies a dead character, but her aura haunts the (unnamed) heroine. Both versions of The Man Who Knew Too Much refer, at least literally, to a minor figure. Why is The Wizard of Oz not called Dorothy Goes to Oz? Why does Mizoguchi’s great Sansho the Bailiff take its title from the name of the villain? It’s not as if Mizoguchi was trying to do an Ian Fleming (Dr. No, Goldfinger).

Perhaps Wizard and Sansho bear their titles because they’re adapted from literary sources that had those titles. But that just pushes the problem back a step: Why do the originals have these titles? And in asking why, I’m not asking for information about what went on in an author’s mind or a story conference. The why question here is about purpose and function. What does the title do in relation to the film’s plot or theme?

For instance, you can argue that the title of The Wizard of Oz works to highlight the seductive world of Oz, so different from Kansas, with the Wizard himself being a figure with one foot in fantasy and one in reality (since the Wizard is actually a prairie mountebank). Similarly, I’m inclined to say that Sansho the Bailiff’s title reminds us of the socially sanctioned cruelty at its center. Zushio and Anju, the fugitive brother and sister, may each escape in a different way, but Sansho’s world remains; it is our world.

Some titles are simply place names, like Casablanca, Macao, Philadelphia, or New York, New York. Others specify dates: 1860, 1900, 1941, 1984. In both strategies, the title often evokes symbolic associations or parallels with the here and now.

The title can refer to the core situation, as with Back to School or Being John Malkovich, or to a key scene, as in Sophie’s Choice and Gunfight at the OK Corral. This can get abstract and metaphorical. Housekeeping features a very offbeat approach to housekeeping. The Birth of a Nation characterizes America reborn after the Civil War. Being There describes more or less all that the cipher-like hero does. The title can even predict the action, as in The Great Escape, A Man Escaped, and Killing of a Chinese Bookie. In these instances we have anomalous suspense: Why and how will an announced action be carried out?

Reaching for the Moon (1917/ 1930/ 1933)

More rarely, the title can refer to the film’s central formal device. Through Different Eyes and Vantage Point announce that they will play with subjective point of view. The Blair Witch Project justifies its title by posing as a dossier of found student footage. The Prestige warns us that a magic trick’s surprise payoff might well be matched by one at the end of this movie. Kristin and I have long assumed that the title of Tati’s Play Time refers not only to the anarchic relaxation unleashed in the Royal Garden restaurant but also to the movie’s own perceptual strategy of making us see amusement in banal incidents.

Hitchcock, the tireless formalist, provided titles that give away his game. Rear Window announces a stationary viewpoint and a limited field of action. More fancifully, you could take Rope as announcing the film’s sinuous long takes. Family Plot is nicely equivocal, referring at once to a communal grave, a conspiracy among kin, and of course the movie’s own mysterious plot of knotty kin relations.

Then there are the generic characterizing titles, usually single-word titles like Notorious or Spellbound or Pushover or Identity or Slacker or Speed or even, probably most generic of all, Conflict (borne by at least five films, from 1916 to 1955). Here again, though, we can find puzzles.

We know why Homicidal is called Homicidal, but what purpose is served by calling a movie Psycho? Again, the source book provides the title, but Robert Bloch’s novel is narrated in the first person and the title gives us a big clue about the sort of mind we’re in. Hitchcock’s film presents the story more objectively, and it begins with Marion Crane’s theft. Those critics who see the film as blurring the boundaries between sanity and insanity would say that Marion, who impulsively commits a crime, and Norman are points on a continuum. People we take to be normal have irrational impulses, a point reinforced by Norman’s line, “We all go a little mad sometimes. Haven’t you?” After their conversation about private traps, Marion seems to recognize herself in his question.

Same old song (1997)

Many titles are citations or quotations, and they usually highlight a thematic element. Both Yankee Doodle Dandy and Born on the Fourth of July are drawn from the same song: both offer portraits of patriotism, but in very different keys. Pennies from Heaven is highly, perhaps heavily, ironic, something you can’t say about Meet Me in St. Louis.

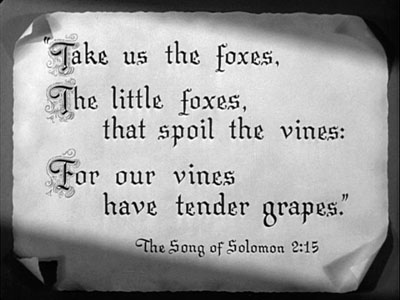

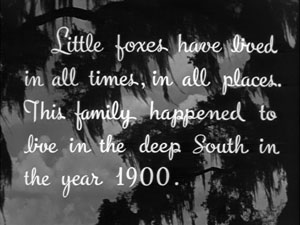

Not all citations are as transparent as these. The Little Foxes explains its title in a prologue, seen above. The Bible verse is then linked to the story we’ll see.

We’re ready to understand the family as creating a milieu that could easily corrupt the tender vine, Xan.

A catch phrase can work too, such as The Sweet Hereafter or It Takes a Thief or It’s a Wonderful Life. You Can’t Take It With You emphasizes pursuing fun rather than riches. Phffft suggests that a couple has split, but how would you explain that outside the U. S.? (The French title is, perhaps surprisingly, Phffft.)

Some catchphrase titles suggest the sort of multiple meanings we saw in Family Plot and Play Time. All That Jazz packs a lot into three words: most basically, a flurry of trivial stuff (pushing our hero into overdrive), but also music and the heights of emotion (being jazzed). You Only Live Once at first suggests seizing the moment, but by the end of the film you begin to think it implies: “Who could bear to live twice?” I especially like The Best Years of Our Lives, which also changes its significance across the film. The bulk of the movie asks: The returning servicemen have given their prime years for us, but how do we reward them? By the end of the movie, the title seems to be suggesting that their best years, of healing and self-understanding and integration into families, lie ahead of them.

I’ve known students, especially from outside the U. S., to have trouble with His Girl Friday. It’s a two-tiered reference. First is Robinson Crusoe’s “man Friday,” his aboriginal servant. But in American slang, a girl Friday is the boss’s closest female assistant, an all-around tough worker and troubleshooter. That’s what Hildy is to Walter Burns, until she decides to marry Bruce and move to Albany. She reverts to her girl Friday role in the course of the film, as the title has predicted she would.

We don’t always know when a quotation is at work. I have always found Some Came Running obscure. The phrase isn’t used in the film, or in the text of the James Jones source novel. But the novel’s epigraph takes a passage from Mark 10: 17:

And when he was gone forth into the way, there came one running, and kneeled to him, and asked him, Good Master, what shall I do that I may inherit eternal life?

This is the passage where Jesus asks the rich man to give all that he has to the poor, apparently as unlikely an event then as now. The problem is that in the Biblical passage, only one came running. The reader has to imagine several characters in the novel as “running” to ask how they will get into heaven. But the citation seems to me a mismatch, since the characters of novel and film aren’t all rich. In any case, without the epigraph tacked to the movie, its significance gets lost. This doesn’t stop me from liking the title, though.

One of my favorite instances of the obscure catchphrase-title is Ozu’s I Was Born, But . . . To decipher it you have to know that during the Depression, Japanese college graduates often couldn’t find work, and the sentence “I graduated, but . . . ,” trailing off, suggesting “. . . I’m unemployed,” was a topical one at the time. Ozu in fact made a film with that title. But then he decided to have fun with it, making a college comedy called I Flunked, But . . . Then came an even sillier extension: When he makes a film about boys, it becomes I Was Born, But . . . [I still have problems…]. Our parallel, I suppose, is the move from Honey, I Shrunk the Kids to Honey, I Blew Up the Kid.

Which reminds me: Titles have a strange habit of speaking for the character. We have I Was a Teenage Werewolf, I Dood It, I Love Melvin, Me and the Colonel, My Favorite Brunette, My Cousin Vinny, Blackmail Is My Life, and so on. This convention points up the difference between literature and film. A book with one of these titles would lead us to expect first-person narration, and it would be strange if it didn’t. A movie with such a title might provide voice-over commentary from the protagonist, as How Green Was My Valley and I Walked with a Zombie do, but more likely it won’t.

For Your Eyes Only (1981)

Many titles seem enigmatic when you first hear them. They create curiosity and build up an urge to check out the film. In most cases, the mystery gets cleared up in the course of the movie. Erik Gunneson’s Milk Punch does this through a bit of action, but more commonly the title is clarified in a line of dialogue or a motif. You have to wait for the very end of They Shoot Horses, Don’t They? or Rio Bravo to get a reference to the title. A good embedded title shifts its meanings, as Best Years does. One scene of Silence of the Lambs explains the title’s relevance to Clarice’s character and shows what drives her to pursue Buffalo Bill. By the end of the film it points toward a moment when her inner pain will start to fade. And the title may reverberate beyond that moment, pointing to larger themes of injured innocence in a world of slaughter.

Sometimes the title is more oblique. Take North by Northwest. Many critics believe that it refers to Hamlet’s confession that “I am but mad North-northwest: When the wind is southerly, I know a hawk from a handsaw.” Roger Thornhill, caught off balance by the espionage game he’s plunged into, could be said to have lost his bearings. But I’ve always thought that the compass-point title logo and the cross-hatched latitude/ longitude array that launch the movie prepare us for travel, in a roughly westerly, then northwesterly direction (New York-Chicago-South Dakota). And when Roger is sent from Chicago to Rapid City, he travels by airliner: He flies north, by Northwest. A Hitchcock joke?

We occasionally encounter a title that isn’t explained in the course of the action, so we are invited to ponder its implications. 8 ½ is a famous example; insiders know Fellini treated it as an opus number (seven features + two shorts + this new feature = 8 ½). American Graffiti can refer to the transitory events of the single night the film shows—the kids have scrawled their dramas on the town in one long summer blast. But I think you can also read the title as referring to the pop tunes that engulf and comment on the action. Americans write their graffiti on the airwaves.

In recent times Hong Kong films have tried to make their English-language titles more comprehensible, but in the golden years there were some delirious ones. We had Banana Cop, Wheels on Meals, Why Wild Girls, Gun Is Law, Tiger on Beat, Devil Fetus, Burning Sensation, Boys?, Kung-Fu vs. Acrobatic, Evil Black Magic, Ghost Punting, Takes Two to Mingle, Vampire’s Breakfast. . . Even Chungking Express and Ashes of Time aren’t straightforward. A real problem in studying Hong Kong films seriously is to explain to people that a movie called Police Story or Naked Killer can be pretty interesting. And if the titles don’t perturb them, the subtitles will.

But most of the Hong Kong titles are inadvertently puzzling, sort of accidental surrealism. Of course Surrealist filmmakers have given us many willfully meaningless titles, such as Emak Bakia and The Andalusian Dog. Arguably Brazil and even A Hard Day’s Night are in this vein (although I think that both of these can be explained in roundabout ways).

Today’s American films seem drawn to recherché titles. I heard Jonathan Caouette remark that he chose the title Tarnation for reasons he couldn’t specify; it just seemed to fit. One catchphrase, “the elephant in the room,” has founded two movies, but in such an abbreviated form—Elephant—that you might not recognize the link. I never thought I’d find synecdoche on a movie credit, since few Americans know how to pronounce it, let alone know what it means. But trust Charlie Kaufman to give it a try. (He also inadvertently stole a pun I’ve been using in film theory courses since the seventies.) But at least I think I get the title’s point, given the protagonist’s obsession to build a miniature city. Other titles are flat-out baffling.

Take Reservoir Dogs. Tarantino says “it’s more of a mood title, it just sums up the movie, don’t ask me why.” (1) I like the title. I just don’t understand why it works so well. Do certain dogs guard reservoirs, as some guard junkyards? Are these guys as vicious as dogs, as dirty as dogs, or doggy in the sense of losers, or what? In other words, why does it seem more fitting than, say, Sump-Pump Ferrets?

Despite the logo showing faces spilling out of a blossom, Magnolia doesn’t explain its title unless you dig around outside the film. During the rain of frogs, the traffic collisions take place on Magnolia Boulevard in the San Fernando Valley. So in a way, Magnolia is one point of convergence for several of the story lines that crisscross the plot. But that’s pretty thin motivation.

What about Syriana? Before I went to the film, I had heard that the title referred to an imaginary, prototypical Middle Eastern territory used in Pentagon war games and computer simulations. But Stephen Gaghan, in another Creative Screenwriting podcast, supplies details:

It was a real term. I heard it for real in a very conservative think-tank, where they said, “We’re going to redraw the map in the Middle East, we’re going to make a new country out of Syria, Iraq, and Iran—the borders of ancient Persia, less Pakistan. We’re going to call it Syriana.” I’m like, “Excuse me? Would you repeat that?” So I shot it, I had William Hurt explaining it. But I didn’t think it helped at the end of the day. We’re not going to make a new country in the Middle East right now.

As he saw the collapse of America’s invasion of Iraq, Gaghan came to believe that explaining the title would date the movie.

I wanted to go for a title that couldn’t be pegged to right now. You notice there’s no reference to Iraq in the movie, there’s just the most passing reference to 9/11, which was an improv thing we did, and there’s no Israel. I wanted the more permanent sense of what it is inside of men, particularly men in the west, that makes them believe that they can remake any region to suit their own purposes. . . . I wanted it to be specific to the film, not to the time. So that if you think about the tone of the film, when you think about what happened in the movie, it would only be Syriana, and Syriana could not skid into some other reference point.

Then there’s Cloverfield, which I’ve discussed earlier this year. Part of the movie’s mystique is that nobody can agree on what the title refers to. The creature? Central Park, where the video camera is found? An exit on California Interstate 10, near where producer J. J. Abrams has his office? On this last option, screenwriter Drew Goddard says no way:

If we would do that, we would be dicks. We would be assholes.

I don’t want to get into the labyrinthine question of the relations of Cloverfield to Lost and to the film’s viral marketing campaign online. What interests me is the fact that part of the fun around, if not exactly in, the film is playing with all these possibilities . . . and waiting to see if a sequel will explain further. Perhaps a teasing title can help get people into theatres for a followup movie.

Finally, Primer. Not only do I not understand the significance of the title; I don’t know how to pronounce it.

I Love a Mystery (1945)

Why have we seen such a rise in cryptic titles in recent years? Several factors seem important. A puzzling title lifts your film above the clutter and creates buzz as people wonder what this movie could be about. This buzz factor is multiplied by the Internet. The title can be researched through Google and discussed endlessly in chatrooms. Filmmakers know that we can revisit a film on video whenever we want, so the movie can be rescanned by eager eyes searching for clues to the title’s meaning. Mystery titles summon up the geek in us.

Which means that the current wave of peculiar titles probably owes a lot to Tarantino. In the interview I already cited, Tarantino stressed that that title of Reservoir Dogs let the audience play with the possibilities.

The main reason that I don’t go on record is because I really believe in what the audience brings. . . . People come up to me and tell me what they think it means and I am constantly astounded by their creativity and ingenuity. As far as I’m concerned, what they come up with is right, they’re 100 percent right. (2)

But then, as Jonathan Walley pointed out to me, cool opacity isn’t confined to movie titles.

Band names have always been evocative: The Rolling Stones weren’t literally rolling stones, The Pixies not literally pixies. But what many of them evoke now strikes me as much more obscure and, to quote Grandpa Simpson, “weird and scary”: System of a Down, Teeth of Lions Rule the Divine, One Day as a Lion, My Morning Jacket, etc. Many of these are alternative bands, and many of the films with these obscure titles are alt/indie films, or at least films with those pretensions, so there’s a parallel there, I’d say. The willful obscurity of title, of band or film, evokes an ironic, think-outside-the-box, you’re-not-meant-to-get-it indie attitude that appeals to the intended audience.

That is, obtuse titles for an acute public.

For comments, suggestions, and memory-jogging, thanks to the Badger Filmies: Susan Antani, Colin Burnett, Andrea Comiskey, Sydney Duncan, Stew Fyfe, Jason Gendler, Doug Gomery, Jonah Horwitz, Tristan Mentz, Jason Mittell, Tim Palmer, John Powers, Brad Schauer, Chris Sieving, and Jonathan Walley.

(1) Quoted in “Reservoir Dogs Press Conference,” in Quentin Tarantino Interviews, ed. Gerald Peary (Oxford: University of Mississippi Press, 1998), 38.

(2) Some writers have hazarded that the title derives from Tarantino’s awkward pronunciation of Au revoir les enfants, coupled with Straw Dogs, but as far as I can tell, this relies on a second-hand source–ie, a former girlfriend–and Tarantino hasn’t confirmed it.

Bs in their bonnets: A three-day conversation well worth the reading

From DB:

The Film faculty and graduate students at the University of Wisconsin—Madison are a close-knit bunch. Keeping in touch via email, we exchange ideas about teaching and research, as well as passing along gossip and peculiar things that appear on the Internets. Our community includes grad students and alumni from several generations. The youngest are taking courses now; the most senior were here in the early 1970s, and they still have all their marbles.

Over three days earlier this month, there was a lightning round of exchanges on B films. With the permission of the participants, I’m posting highlights of the correspondence here because it exemplifies one way in which the Web can advance film studies.

Most film writing on the web comments on current films or video releases. Nothing wrong with that. But if you’re a researcher into film, you also want to talk about history. It’s rare to find an online debate about historical evidence and alternative interpretations of that evidence.

So to scratch my academic itch, I give you mildly edited extracts from our UW cyber-dialogue. You’ll see some hard-working professors practicing imaginative pedagogy, and you’ll find ideas for research and teaching. You’ll also see, I hope, that film studies can make progress by asking precise questions and refining them through inquiry and critical discussion.

Note to film scholars: Blogs are seldom cited in academic writing, but if you intend to use this material in your own research, it would be courteous to mention these esteemed sources, as they mention others.

To be a B, or not to be a B

First, a little background. Today sometimes we call low-budget films or just poor quality movies “B movies.” But across the history of Hollywood the term had a more specific meaning. You can find a primer at GreenCine, but here’s a little more industrial context.

During the heyday of the studio system, most theatres ran double bills—two movies for a single ticket (along with trailers, news shorts, cartoons, and the like). Very often the main feature, or A picture, was a high-budget item with major stars from a significant studio. The B film was low-budget, ran to only 60-80 minutes, and showcased lesser-known players. A B tended to be distributed for a flat fee rather than a percentage of the box office.

(I’ve just distinguished Bs in terms of its level of production; as you’ll see from the dialogue, we can think of them in other ways too.)

MGM, Warner Bros., Twentieth Century-Fox, and other major companies made B pictures as well as As. Often the B film was part of a series. Fox had Mr. Moto and Charlie Chan, MGM had Andy Hardy and Dr. Kildare. Since the most powerful studios owned theatres as well, the B film filled out the double bill with company product. Moreover, the Bs allowed studios to make maximum use of the physical plant. Sets built for an A picture could be used for a B, and actors idling between big projects could take small parts in Bs. Bs could also serve as training ground for stars, crews, and directors who might move up.

Other companies concentrated wholly on making B pictures. The most famous of these so-called Poverty Row studios are Monogram, Republic, Mascot, and Producers Releasing Corp. Besides turning out stand-alone Bs, the Poverty Row studios specialized in serials, like Don Winslow of the Navy and Hurricane Express (1932, Mascot, with John Wayne, right).

Other companies concentrated wholly on making B pictures. The most famous of these so-called Poverty Row studios are Monogram, Republic, Mascot, and Producers Releasing Corp. Besides turning out stand-alone Bs, the Poverty Row studios specialized in serials, like Don Winslow of the Navy and Hurricane Express (1932, Mascot, with John Wayne, right).

Still other studios, the so-called Little Three, hovered between A and B status. Universal, Columbia, and RKO were smaller companies, and some of their A pictures might have been considered really B’s, in terms of budget and resources. This is one theme of the conversation that follows.

As the major studios cut back production after the war, many B pictures were made as independent productions. Double bills in the US persisted into the 1960s, and Roger Corman and other producers turned out B-films for drive-ins, declining picture palaces, and rural theatres. Still, the prime years of B films were the 1930s-early 1950s. They have always been an object of admiration for cultists; recall that Godard dedicated Breathless to Monogram. Important directors like Anthony Mann and Budd Boetticher started in B production. Several Bs, notably noirs and horror films, are staples of cable and home video.

Want to know more? Here’s some essential reading: Tino Balio’s The American Film Industry, rev. ed. (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1985); Douglas Gomery, The Hollywood Studio System: A History (London: British Film Institute, 2005); Todd McCarthy and Charles Flynn, eds., Kings of the Bs: Working within the Hollywood System (New York: Dutton, 1975).

Now to the question of the day.

Day 1: What do I teach?

It all began on 6 February. (Cue harp music and dissolve here.) Paul Ramaeker of the University of Otago asked an innocent question….

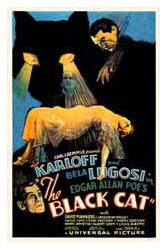

OK, so I am running a grad seminar (or, more precisely, our closest equivalent- a 4th year Honours course) on Classical Hollywood Cinema. I want to spend time on the industry, obviously, which raises questions about what to screen for those weeks. I thought an A pic and a B pic. For the A, I was thinking about Robin Hood. For the B, I’m not sure, but I had for other purposes been considering a double bill of The Black Cat and I Walked with a Zombie. Now, the latter, I know, is a B pic; but is The Black Cat a B? It’s about an hour, which suggests a B and it’s not got a lot of sets. But it’s got Lugosi and Karloff, who surely were two of Universal’s bigger stars at the time, right? So which is it?

Any other good B pic recommendations are welcome.

The replies came fast. First, from Jane Greene of Denison University:

I do the same thing in my history class and I’ve found that Casablanca and Detour work well. It helps that most students have heard of Casablanca and a surprising number have seen it. You can point out how this “timeless classic” was very much a product of collaboration, how the star system, budget and schedule determined the look of many scenes, and it also allows you to discuss censorship… I mean self-regulation. (See Richard Maltby’s “Dick and Jane Go to 3.5 Seconds of the Classical Hollywood Cinema” in a little-known book called Post-Theory.)

Aljean Harmetz’s The Making of Casablanca is coffee-table-y, but she did consult tons of production and publicity material and there are reproductions of production documents (script pages, even a Daily Production Report!).

And, if yer willing to go Poverty Row for yer B Film, Detour just rocks. It’s so obviously re-using 2-3 sets and locations, has the foggiest scene ever shot, and long voiceovers that sound deep and poetic and take up half the film. The kids love it. And it could ease you gently into the waters of film noir, should you wish to go that way (and I bet you do).

And, if yer willing to go Poverty Row for yer B Film, Detour just rocks. It’s so obviously re-using 2-3 sets and locations, has the foggiest scene ever shot, and long voiceovers that sound deep and poetic and take up half the film. The kids love it. And it could ease you gently into the waters of film noir, should you wish to go that way (and I bet you do).

Leslie Midkiff DeBauche of UW—Stevens Point also shared a teaching technique.

I teach the 1930s with a colleague in the History Department and we like to create a whole program: News Parade of 1934 from Hearst Metronome News; Three Little Pigs (1933), followed by the first half of a documentary called “Encore on Woodward” about the Fox Theater opening in Detroit. It opens in 1929 and is wonderful–it has clips of late silents like Seventh Heaven, sound comes, and we end it after a woman remembers how her boyfriend proposed to her, in the balcony, during Robin Hood. We usually show the 1936 (I think, it could be 1934) year-in-review newsreel that is on the Treasures of the Archive

I set of DVDs and the feature we use is It Happened One Night. What the students like best though is the popcorn and the give-a-ways between the parts of the program: Nancy Drew and Superman, a bag of groceries with food items from 1930s–turns out to be current student food–Bisquick, Snickers, Jiffy peanut butter,Ritz crackers. The grand prize bank night equivalent is an A on the final exam. They freak! It is like they won big money.

From Notre Dame comes Chris Sieving on RKO:

In researching Lewton last year I found a few sources that argue vehemently that the Lewton-Tourneur-Wise-Robson horror films were not B films, but more like nervous As: budgets were decent, prestige factor was high, occasional name stars (like Karloff).

Another veddy interesting and perhaps more “authentic” B film, besides Detour, is Stranger on the Third Floor (1940). It contains some very bizarre and magical Peter Lorre acting, plus some people call it the “first” film noir. (Speaking of film history myths that need debunking…)

Lea Jacobs, doyenne of Film Studies here in Madison interjects:

I would think The Black Cat is a B, not only because of running time but because of genre. When I was researching the distribution of B’s at RKO I was surprised by the way the horror films made by Val Lewton’s unit at RKO (many justly celebrated today) were treated as the lowest of the low–opening alongside films with titles like Boy Slaves at the small Rivoli or Rialto theaters in New York for very short runs, and later booked in and out of theaters nationally on an ad hoc basis. See my article, “The B Film and the Problem of Cultural Distinction,” Screen 33, no. 1 (Spring 1992): 1-13. I also think that Universal simply wasn’t making many A films in 1934, even with their recognizable stars.

I would think The Black Cat is a B, not only because of running time but because of genre. When I was researching the distribution of B’s at RKO I was surprised by the way the horror films made by Val Lewton’s unit at RKO (many justly celebrated today) were treated as the lowest of the low–opening alongside films with titles like Boy Slaves at the small Rivoli or Rialto theaters in New York for very short runs, and later booked in and out of theaters nationally on an ad hoc basis. See my article, “The B Film and the Problem of Cultural Distinction,” Screen 33, no. 1 (Spring 1992): 1-13. I also think that Universal simply wasn’t making many A films in 1934, even with their recognizable stars.

When I teach the B film I like to show Detour and Moon Over Harlem (now out on DVD). The latter has two really amazing scenes in a movie made for less than $10,000. But maybe that is too Ulmer heavy. Anyway you can’t go wrong with I Walked with a Zombie.

Kevin Heffernan of Southern Methodist University weighs in.

Great movies, Paul! “Cries of pleasure will be torn from” your students (as they were from our hero in S/Z).

Great movies, Paul! “Cries of pleasure will be torn from” your students (as they were from our hero in S/Z).

The Black Cat is an A picture, I think. All of the Universal horror movies ran between 65-71 mins, so this is just under their average. Also, names above the title usually point to an A, and I’m virtually certain the movie would have played a percentage (rather than a flat fee) in its initial engagement. I would imagine that a Universal horror picture sold well in subsequent run as a component in double bills, so they would be sort of de facto B pics in some situations.

And it is worth mentioning to your students, as Elder Goodman [Douglas] Gomery pointed out years ago, that the Deanna Durbin musicals were much more financially successful for Laemmle et cie than the horror movies. They’re all out on video now. Ghastly, unwatchable, wretched.

Lea Jacobs replies:

Universal is one of the little three in 1934, and, unlike today, when horror films command high budgets and garner big returns, in the 1930s horror films and sci fi were the stuff of serials and the bottom half of the double bill. I would have to see a contract before I believe it played for a percentage. One way, apart from that, to decide, is to look at where it opened in New York, how long it played and where it played subsequently in the key cities.

Doug Gomery, Resident Scholar at the University of Maryland, is succinct on I Walked with a Zombie:

RKO in the 1940s was a low budget studio and Floyd Odlum owned it. Odlum went cheap after his experiment with the likes of Citizen Kane. So it was B pure and simple.

Then Hughes bought it after the war and dabbled with his strange way of doing things.

It’s now 5:30 on the same day, but are our eager scholars tired? You have to ask?

Lea Jacobs follows up:

It is pretty safe to assume that most Universals in the 1930s were in the B range–their films were shown on the bottom of the double bills in theaters owned by the Majors. Even in the 1920s one reads Variety complaining about the cheapness of Universal’s product. A far cry from when it was taken over by Doug’s favorite Lew Wasserman.

Jim Udden of Gettysburg College jumps in, invoking the founder of film-industry studies at UW, Tino Balio:

Tino does discuss this issue in Grand Design. According to him, Frankenstein and Dracula are clearly A pics, part of Universal’s strategy to break into the first-run market, since, as we all know, they had very few theaters of their own. But Black Cat is only one third the budget of Frankenstein, according to the figures in IMDB.com. Does that make it a B pic? Perhaps. Yet it seems to me that this film could still have been marketed and released like the initial Universal Horror films, riding on their coat tails, so to speak, but with less actual money invested in the production.

Tino does discuss this issue in Grand Design. According to him, Frankenstein and Dracula are clearly A pics, part of Universal’s strategy to break into the first-run market, since, as we all know, they had very few theaters of their own. But Black Cat is only one third the budget of Frankenstein, according to the figures in IMDB.com. Does that make it a B pic? Perhaps. Yet it seems to me that this film could still have been marketed and released like the initial Universal Horror films, riding on their coat tails, so to speak, but with less actual money invested in the production.

So was Black Cat more often one of these “featured” features, or was it usually the bottom half of the double bill, as Lea says? Maybe this is an AB pic?

This to me, sound like a researchable topic! (I myself have not time for this, unfortunately…)

Lea Jacobs replies:

Yes, Jim, I agree, a researchable question that I don’t have time for either. But a distinction that can be made, without research (or prior to it) is one between A/B at the level of production planning and budget and A/B at the level of distribution. Sometimes relatively “cheap” films were marketed as As (Variety usually complains about this its reviews!). Thus, to be really certain of how a film lines up, you have to look at both the budget ranges at the studio at the time of the films’ production, and the distribution pattern, including, of course, whether it was distributed for a percentage or flat fee.

Kevin Hagopian, Penn State University, comes rolling in at 10:30 pm.

* The trouble with some of the great B’s, like The Black Cat, Detour, and I Walked with a Zombie is that they’re so good that they don’t give a sense of the real purpose of the “B,” which was to hold down half of a double bill, and amortize overhead at the studios over a larger number of opportunities for revenue – that is, individual films. A comparison of scenes from an A film and a B film using the same standing sets does this nicely; I use the RKO New York street set, visible in Citizen Kane and Stranger on the Third Floor, as an example. (A great visual example I’d like to make would be Lewton’s Ghost Ship, which is said to be a script written for an existing ocean liner set, but I haven’t seen that set in another RKO film as yet.)

*I’ve often done a clip show that involves:

A. Clips from films like the Lewtons, or the Schary-Rapf films at MGM (like Pilot #5 and Joe Smith, American), or one of the series films, like a Maisie film. These films show that the resources of a big studio, such as talent, standing sets, skilled cinematography and editing departments, etc, could generate a film that, while it might have been double feature fodder, still maintains a sense of `quality’ that, perhaps, studios wanted to maintain for purposes of brand equity.

B. Clips from fairly awful B’s, like the Dick Tracys or Tim Holt Westerns at RKO, which show what could happen when questions of production value were not attended to quite so scrupulously, simply because, given the films’ titles, they were likely to draw from a market which did not make attendance decisions in the same way as patrons of, say, Pilot #5.

C. Clips from minor studio “B” westerns, ala Buck Jones. REALLY gets the point across about the relationship between production expenses and expected grosses; clearly, these films were made on a precise calculus. As films, of course, they’re nowhere near as interesting as the Lewtons or RKO “B’ noirs like The Devil Thumbs a Ride, but they work, particularly when students can’t really tell the difference between a Buck Jones, a Tom Mix, or a Three Mesquiteers – that’s sort of the point. Peter Stanfield’s work on “B” Westerns, however, shows how the signifying practices of the B Westerns, production values aside, could be truly divergent from anything in the A film canon, and worth studying. But in defense of my students, being trapped in a screening room with a true B Western at full length can be a grueling experience.

*A handout listing the films produced in a single given year by one studio, grouped by genre, and with A or B indicated in each case. 1939 is a good year to do this with, as it contains some of the few studio films students have even ever heard of. They can see how certain studios specialized in certain genres, and how B’s supported A’s in the production calendar.

*Finally, by way of an outro, of course, talking about modern equivalents of B films, and even arguing whether such equivalents exist in the film or cable marketplaces. (Jim Naremore’s chapter on direct to video “erotic thrillers” in his wonderful book on noir, More than Night, can be very helpful here.)

Our researchers retire from the field. But not for too long.

Day 2: Diving for Dollars

Brad Schauer, Ph.D. candidate at UW-Madison fires this off at 9:33 CST on 7 February:

Wow, what a digest I received this morning! With all this B movie talk, I couldn’t resist adding my $.02.

The Black Cat is a tricky case – it was worth flipping through some of the secondary sources to investigate (Senn 1996; Weaver, Brunas, and Brunas 1990, Soister 1999). In a sense, it’s a clear B. The budget was about $90K and was scheduled for a two-week shoot. Compare this to next year’s Bride of Frankenstein, which cost $400K and took Whale about six weeks to film. Plus, Black Cat has all the wonderful hallmarks of a quintessential B: lurid storyline, short running time, sometimes incomprehensible narrative (due in this instance to censorship), etc.

And it was devalued by the critics because of its genre and the concomitant transgressive material (the flaying scene is still shocking).

However, the film was also a big hit for Universal, its top moneymaker for 1934. Looks like it brought in rentals around $250K – which isn’t a lot, but it suggests a percentage release, at least in its initial run. Variety also said it had “box office attraction” because of the current popularity of Lugosi & Karloff, teamed for the first time. Someone would have to investigate its distribution patterns to be sure, but it kinda looks like a B picture that was sold as an A, as Lea suggested. Maybe Universal knew it could throw a cheap movie out there and it would succeed based on the popularity of the genre and the stars. It’s a kind of precursor to all those low-budget, highly-profitable horror films like Halloween and Saw. So for me it’s about 4/5th B, 1/5th A.

Would I show it as an example of a B? As Kevin Hagopian mentioned, it’s really much too good to be a truly representative example, but students will probably like it more than a Dr. Kildare movie or something. If you really want to sock it to them, dig into the Sam Katzman filmography. Try one of the Jungle Jims or the Lugosi Poverty Rows.

David already mentioned the real gems of the studio Bs, the Motos. The Chans are great too. (I can even watch the Monogram Chans, although the Karloff Mr. Wongs can be a real slog.) As far as other mystery series go, the Universal Holmes films are extremely well done, the Dick Tracys, Perry Masons, and Torchy Blaines are a lot of fun, and I have a soft spot for the Falcon films due to AMC early morning reruns in my childhood. The Kitty O’Day mysteries are on my “to watch” pile, but I’m not optimistic. Follow Me Quietly (1949) also comes to mind as a great B-noir.

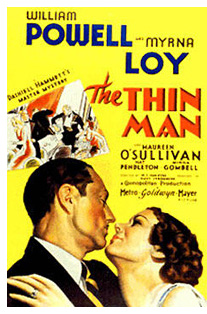

And also, the Thin Man movies weren’t really Bs. Not responding to anyone – just needed to get that out there. Closer to Bs would be MGM’s Sloan mystery knockoffs, which are fun too (especially Fast and Furious, which is fortunate enough to have Rosalind Russell).

Whew, thanks for reading if you made it this far.

As a new day dawns on Texas, Kevin Heffernan has more thoughts.

Thanks for the info, Brad. Yes, Black Cat is a curious hybrid case. For a “truer” example of a Karloff/Lugosi B from Universal, see The Raven from the following year–most notably in its use of fairly minimal, obviously left-over sets (nothing like the very bold production design of Black Cat). And, although I recall that Kristin is a Lew Landers fan (didn’t she call him “lightly likeable at least” in Breaking the Glass Armor?), his name was somewhat synonymous with quotidian program pictures in the 30s and 40s.

Thanks for the info, Brad. Yes, Black Cat is a curious hybrid case. For a “truer” example of a Karloff/Lugosi B from Universal, see The Raven from the following year–most notably in its use of fairly minimal, obviously left-over sets (nothing like the very bold production design of Black Cat). And, although I recall that Kristin is a Lew Landers fan (didn’t she call him “lightly likeable at least” in Breaking the Glass Armor?), his name was somewhat synonymous with quotidian program pictures in the 30s and 40s.

My assertion that Black Cat was an A referred to my understanding of the terms of its first-run distribution . But I actually had little evidence, I have discovered, as I looked over my notes on the movie from Tino’s seminar a few years back.

Lea and Doug’s observations about Universal’s “Little Three” status and the general role its horror pictures played in the larger patterns of distribution seem spot on to me and of course became more prevalent (inflexible, even) in the post-Laemmle years. The only exception to this that I can think of was Son of Frankenstein, which was U’s entry in the superproduction cycle of 1938-39 (stars on loan from other studios, spectacular production design, initial plans to shoot in Technicolor, etc), but that movie was really the last gasp of the A horror pic at the studio, I think.

And at 10:10 AM CST Lea Jacobs is back at the keyboard.

I guess Brad has the last word on The Black Cat. Nothing like doing the research.

Now about the Thin Man series. In the essay on film budgets at MGM that appeared a few years back, I recall that these films were in the “B” range for MGM (about $250,000). (See H. Mark Glancy, “MGM Film Grosses—1934-1948: The Eddie Mannix Ledger,” Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television 12, 2, 1992: 127-144.) This is a lot of money relative to what other studios were spending on B films, of course, but all of MGM budget ranges were high relative to the other majors (the average MGM A was between $700,000 and $1 mil as I recall). So I agree that the Thin Man films are elegant and well dressed and don’t fit anyone’s conception of a B, but at least when considered from the perspective of film budget categories at MGM, wouldn’t these count as Bs? Or, put another way, what would you count as an MGM B?

Now about the Thin Man series. In the essay on film budgets at MGM that appeared a few years back, I recall that these films were in the “B” range for MGM (about $250,000). (See H. Mark Glancy, “MGM Film Grosses—1934-1948: The Eddie Mannix Ledger,” Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television 12, 2, 1992: 127-144.) This is a lot of money relative to what other studios were spending on B films, of course, but all of MGM budget ranges were high relative to the other majors (the average MGM A was between $700,000 and $1 mil as I recall). So I agree that the Thin Man films are elegant and well dressed and don’t fit anyone’s conception of a B, but at least when considered from the perspective of film budget categories at MGM, wouldn’t these count as Bs? Or, put another way, what would you count as an MGM B?

Doug Gomery adds in re MGM B-pictures:

Nicholas Schenck was no great man, but he ran Loew’s/MGM from 1927 to 1954. To him the Thin Man series were Bs from his studio. Remember block booking? These simply made MGM a more attractive package. The question of A v. B is at its heart a budget decision and then a release one. The New York-based men, like Schenck, made those decisions.

Day 3: B Mania Subsides; some answers, more questions

8 February: Brad Schauer revisits Nick and Nora:

Real quick about the Thin Mans before I run to lecture: I know I was being a bit contentious when I said they weren’t Bs. Lea and Prof. Gomery are absolutely right that if you go by budget, they’re Bs…at least initially. But by the time we get to Another Thin Man (1939), the budget is up to $1.1 mil, only a couple of Gs less than Ninotchka. 1944’s Thin Man Goes Home is budgeted at $1.4 mil, only about $500K less than Meet Me in St. Louis (!).

Real quick about the Thin Mans before I run to lecture: I know I was being a bit contentious when I said they weren’t Bs. Lea and Prof. Gomery are absolutely right that if you go by budget, they’re Bs…at least initially. But by the time we get to Another Thin Man (1939), the budget is up to $1.1 mil, only a couple of Gs less than Ninotchka. 1944’s Thin Man Goes Home is budgeted at $1.4 mil, only about $500K less than Meet Me in St. Louis (!).

Another reason they don’t seem like Bs to me is that they were consistently among the top grossers for MGM in the ’30s. But so were the Andy Hardys, you might argue, and they’re clearly Bs.

Except…from what I could tell from analyzing the distribution patterns of the ’35-’36 season (not done this morning, don’t worry), After the Thin Man played in major first run theaters, and hardly ever with a second feature until it hit the nabes (neighborhood theatres). It was distributed like a big deal A, and you can sense the exhibs’ excitement in the trade press that another Thin Man installment was coming out.

Finally, we can look at the running times. MGM’s Bs were sometimes longer than other studios, but the first sequel After the Thin Man is nearly two hours long. Compare that to MGM’s Sloan mysteries (Thin Man knock-offs), which clock in at 75 minutes each.

So, like The Black Cat, the Thin Man films seem an unusual case. The first installments may have been budgeted as Bs, but as the series caught on, it was treated like an A property, both in terms of production and distribution – compared to the Andy Hardy films, for instance, whose budgets remained quite low for the entire series.