Archive for the 'Directors: Ford' Category

The wayward charms of Cinerama

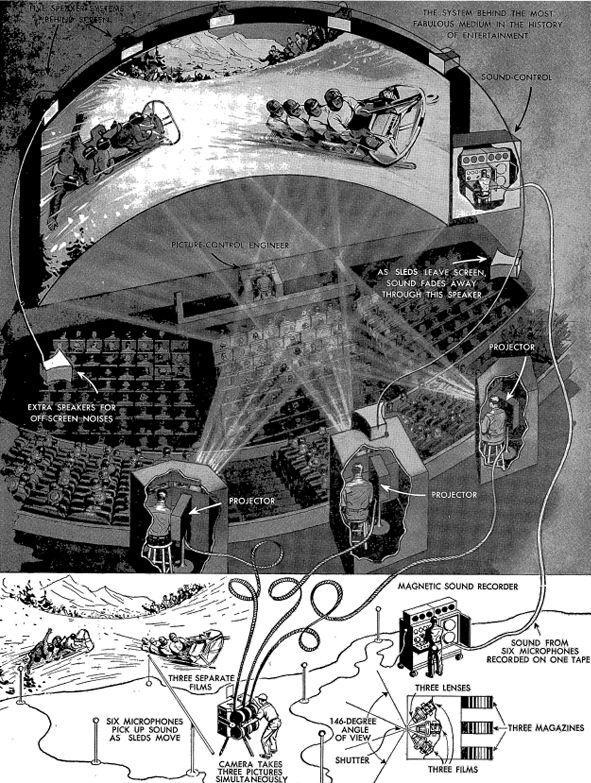

From Cinerama Holiday souvenir book, 1955.

DB here:

Two slumbering potential giants stirred in the last months of 1952, and as 1953 got underway the motion picture industry was faced with the greatest upheaval since sound films revolutionized the industry nearly 26 years ago.

Winfield Andrus, “3-D Finding Its Place,” The 1953 Film Daily Yearbook (New York 1953), 147.

Andrus was referring to 3D and to Cinerama, two technical marvels that promised to revive American filmgoing in the postwar era. In the short term, that didn’t happen. 3D died quickly, and Cinerama remained a novelty before expiring in 1962. But eventually 3D became viable, as the last decade has shown. Moreover, Cinerama’s impact was felt throughout the 1950s. Studios competed with it by introducing other widescreen formats, stereophonic sound, and extravagant roadshow productions. Cinerama, people are starting to point out, was a prototype of what Imax has become. Just as we’re now more interested in classic 3D (see my entry on the reissued Dial M for Murder), we ought to take another look at Cinerama in its more or less pure state.

Devoted aficionados like John Harvey of the New Neon Cinema in Dayton have kept Cinerama alive in theatres, and the challenge has been taken up by other venues. One of the most passionate advocates has been David Frohmaier, whose documentary Cinerama Adventure graced our Wisconsin Film Festival some years back. That documentary showed up on the 2008 DVD release of How the West Was Won, and it’s an essential, affectionate introduction to this most ungainly of film formats.

Now Frohmaier has brought us the 1952 film that started it all. This Is Cinerama has just been released by Flicker Alley, one of our most exacting and adventurous DVD publishers. The whole meticulous package–the film itself, presented in Frohmaier’s Smilebox display, along with an abundance of extras—offers a good chance to think about what Cinerama amounted to.

Cinerama had its ups and downs over a decade. Control of the technology and the venues shifted unpredictably, as did the revenues and profits. But I think that Cinerama’s unique accomplishment lies partly in its unintended consequences. Seeking to become the most realistic form of cinema yet known, Cinerama demonstrates how enjoyably un-realistic, even surrealistic, movies can be.

One hell of a demo

When This Is Cinerama opened at the Broadway Theatre in Manhattan on 30 September 1952, it presented itself as the ultimate package of new entertainment technologies. It was of course in color, which was still something of a rarity in motion pictures. It used stereophonic sound, with five speakers behind the screen and two in the auditorium. The screen itself was a wonder: it was seventy-five feet wide and about 23 feet high, bent in a 146-degree arc. That made the display span fifty feet. Later, some screens would be nearly a hundred feet long and over thirty feet high.

All who saw the film felt that this was an immersive experience. The goal, claimed Cinerama’s inventor Fred Waller, was to approximate what our eyes take in, including peripheral vision. Indeed, Waller claimed that our sense of depth in the world and an image depended on peripheral information. Anyone who has been in a wraparound theme-park attraction can attest to the fact that an image stretching to the edges of sight can provide a pretty compelling illusion, especially if the images carry us forward. You can undergo this illusion in Disney’s Circle-Vision 360°.

Cinerama’s colossal screen size and deep curve dictated a new approach to image-making. No standard 35mm frame could fill such a wide display without losing resolution. The scale of the show demanded three projectors, each trained on one-third of the screen. The image became a triptych, with thin overlaps or “blend lines” demarcating the panels. Naturally, all three had to be exactly aligned and kept in strict synchronization. If one film reel lost frames through a mishap, for future shows projectionists snipped the corresponding frames out of the other two reels.

The projectors were initially housed in separate booths, with a projectionist in charge of each. A fourth booth was given to the sound mixer (off to the right side in the above diagram), who oversaw the multiple track playback at each performance. Yet another staff member was in charge of monitoring the whole performance. Interestingly, the projectors were said to be placed level with the screen, in order to avoid any keystoning distortions of the display. But the diagram above, along with the Cinerama displays I’ve seen, position the projectors fairly high in the auditorium.

The image looked something like the still on the right. Even in this tiny image you can see slight differences between the panels and vignetting along the joins. Projectionists had to ensure that the three panels yielded comparable illumination and color temperature. Each projector’s gate had a little gadget known as a “jiggolo” that ran rapidly along the edges of the frame to blur the blend lines.

The image looked something like the still on the right. Even in this tiny image you can see slight differences between the panels and vignetting along the joins. Projectionists had to ensure that the three panels yielded comparable illumination and color temperature. Each projector’s gate had a little gadget known as a “jiggolo” that ran rapidly along the edges of the frame to blur the blend lines.

To gain resolution, each frame on the film strip used about twice the image area of conventional film. Surprisingly, the image area wasn’t much wider than normal film but it was 1 1/2 times the normal height (that is, 6 perforations high rather than the usual 4). To allow more frame space, the soundtrack was played on a separate magnetic film reel. The resulting images yielded very high resolution.

These sprawling images came from three cameras interlocked into a single bulky unit. The lenses were angled at 48 degrees to one another, turned inward to cross at a precise focal point. The camera lenses, all purpose-made, had a focal length of 27mm–another factor that would yield some striking pictorial effects. All three lenses shared a common shutter and had interlocked diaphragms to ensure comparable exposure. Because flicker would be disturbing on such a wide display, particularly on the edge panels, the film ran at 26 frames per second rather than the usual 24. The aspect ratio varied between 2.6:1 and 2.77:1.

This Is Cinerama was what we’d today call a demo. Lowell Thomas, one of the backers of the process, noted that if they’d told a story with actors, the emphasis would be taken off Cinerama itself, which was “a major event in the history of entertainment.” “The logical thing,” Thomas remarked, “was to make Cinerama the hero.”

The result was a travelogue (a word Thomas hated). After Thomas’ prologue, the film proper opens with the famous ride on a plunging rollercoaster. Then come episodes devoted to the canals of Venice, some church choral music, Scottish pipers, Viennese boy choristers, Spanish dancers, and an excerpt from Aida performed at La Scala. During the intermission Thomas inserts another demo, this time of the surround-sound effects. (We have to remember that stereophonic sound was a big novelty at that point; stereo LPs came later.) The bulk of the second part is spent at the Cypress Gardens leisure park, providing images of handsome men and women at play and climaxing in some exciting water-skiing. This is sort of double product placement–not only promoting the park but also water skis, another Fred Waller invention. The film ends with an awe-inspiring flight crisscrossing America, from New York and the Pentagon to the Golden Gate Bridge, and back to the rugged terrain of the West and Southwest.

In an essay for Cahiers du cinéma, the late Chris Marker pointed out that the film amounts to a religious-popular spectacle. For all the globe-trotting of the first part, the last half is a paean to the splendor that is the postwar USA. The last word spoken, or rather sung, in the film is “America.” Indeed, as many have pointed out, the word Cinerama is an anagram for American. I’ve sometimes wondered about the logo, that peculiarly zigzagged string of letters. It suggests a crumpled snippet of film, with squarish frames like our vertical panels, and its bumpiness evokes the ups and downs of a roller coaster. But there’s no mistaking the logo’s recurring color scheme of red, white, and blue.

In an essay for Cahiers du cinéma, the late Chris Marker pointed out that the film amounts to a religious-popular spectacle. For all the globe-trotting of the first part, the last half is a paean to the splendor that is the postwar USA. The last word spoken, or rather sung, in the film is “America.” Indeed, as many have pointed out, the word Cinerama is an anagram for American. I’ve sometimes wondered about the logo, that peculiarly zigzagged string of letters. It suggests a crumpled snippet of film, with squarish frames like our vertical panels, and its bumpiness evokes the ups and downs of a roller coaster. But there’s no mistaking the logo’s recurring color scheme of red, white, and blue.

Party like it’s 1952

As a novelty, This Is Cinerama succeeded, running for over two years in New York. The system was installed in big-city theatres around the country. At a time when the average price of a movie ticket was $.46, the high-end seats for a Cinerama feature cost $2.80, or $24.34 in today’s currency. The Cinerama organization produced four more episodic travel-centered pictures: Cinerama Holiday (1955), The Seven Wonders of the World (1956), Search for Paradise (1957), and Cinerama South Sea Adventure (1958). Another picture made in a rival three-panel technology, Windjammer (1958), wound up in Cinerama venues as well. By 1957, Variety announced, the first three releases had grossed $60 million worldwide.

The problem was that on those grosses, profits came to only $6 million. Eighty percent of the box office take was used up in operation of the theatres.Morever, the complexity and cost of a Cinerama system meant that very few venues existed; by 1959, there were about twenty screens in the US and another eight or ten abroad, and not all were operating. In addition, overall US movie attendance was dropping, from about 47 million weekly in 1954 to 32 million in 1959.

New management succeeded in opening many more Cinerama theatres on a franchise basis, but the company needed fresh product as well. A coproduction deal was struck with MGM to use the process on fictional features. The results were The Wonderful World of the Brothers Grimm (1962) and How the West Was Won (London premiere, 1962; US release, 1963). To expand the audience, these films were also released in anamorphic widescreen to non-Cinerama venues.

Both films won large audiences, but they failed to make a profit. Soon the company’s theatres began exhibiting 70mm film releases under the Cinerama brand. The films were shown on curved screens, but with single-lens projection. The first of these releases was It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World (1963); eventually even 2001: A Space Odyssey (1967) would be exhibited in “Cinerama.” In the course of these years, the company was acquired by Pacific Theatres, where it still resides. Classic triptych Cinerama was gone.

I never saw it in its prime.

I did see How the West in its original anamorphic release, and that has stayed with me for a couple of reasons. First, I was moved by it. It’s kitsch in many ways, but there are several exciting and touching scenes. Moreover, even as a squeaky-voiced teen I recognized something genuinely weird about the way it looked. Its imagery haunted me, though I didn’t have ways to understand them. Many years later, writing portions of a book that became The Classical Hollywood Cinema, I couldn’t watch any of the Cinerama travelogues in archives. I had to content myself with watching pink, cropped 16mm anamorphic copies of How the West Was Won. In all, it was very hard to get a sense of what the thing looked like (let alone sounded like).

Not until 2003 did I see both This Is Cinerama and How the West Was Won in the three-panel format, during a conference on widescreen cinema held at the National Media Museum in Bradford, England. That experience was wonderful, and it left me wanting to study the films more closely.

Now I can, and you can too. David Strohmaier has devised a transformation that captures the shape of a Cinerama projection. He calls it the Smilebox. The Flicker Alley DVD of This Is Cinerama is in Smilebox, as you see from my Venetian image above. Warner Bros’ 2008 Blu-ray release of How the West Was Won provides both a Smilebox version and a wider-than-CinemaScope letterbox version.

Through painstaking restoration by Greg Kimble and others, the films look clean and bright. Digital cleanup has regularized the color values from panel to panel and nearly eliminated the blend lines. The result conforms to what the makers would surely have preferred–a greater sense of uniform tonality, light, and space across the frame than surviving Cinerama images have.

For anybody interested in the history of American cinema, the Flicker Alley DVD is essential. It provides a long-missing chapter in the development of widescreen filmmaking. This Is Cinerama is a documentary that is also a document of postwar American pride, of film technology, and of the movie business. But I think it represents even more. For the most part neither Smilebox nor digital restoration has removed the peculiarities that, perhaps perversely, fascinate me about this unique format.

Nice big image you got here. Be a shame if anything happened to it.

Cinerama camera in a mock covered wagon for How the West Was Won.

Like any picture-making process, Cinerama captures the three-dimensional world on a two-dimensional surface. Unusually in the history of cinema, it does it with a semicircular array of cameras. The images from those cameras are projected on a corresponding semicircular surface, in the hope that they will simulate not only the spatial layout in front of those three lenses but also the way the world looks to us.

Fred Waller thought that his invention provided greater realism, because our vision subtends a horizontal arc wider than that of conventional camera lenses. Fred fell a few degrees short, though. Claiming that we take in about 160 degrees, he thought that 146 degrees was a good approximation, but our visual field is actually a bit wider than 180 degrees. (Without turning our head, we can roll our eyes.) More important, though, is the assumption that a faithful image of the world should try to capture the curvature of the image as it passes through the cornea to the retina. We see a bowed world, many have claimed, so our pictures should present the way things look.

Yet there’s a difference between visual sensation and visual perception. Even if the light from the world hits our photoreceptors in a partial or distorted way, what we see is regular and unified. On our retinas, near things loom large and distant things look tiny, but we’ve evolved to adjust to the distortions in early stages of vision and see things in normal size. A person ten feet away is twice as large on our retina as somebody twenty feet off, but that’s not the way they look. We don’t see our retinal image, any more than we see the wildly misshapen image of the world projected to brain areas. The eye is a part of the brain, and the brain reworks the stimulus–cleans it, enhances it, corrects it, straightens it out, and gives it a stability that isn’t there in the raw input.

For the most part, normal camera lenses approximate the way the world looks to us after our brain has processed visual signals. Most images show straight-edged walls and sidewalks, railroad tracks meeting at the horizon, proportional human beings. When Cinerama or other nonstandard image-making technologies present distortions to our eyes, we take them for what they are: not “what we really see” but rather pictorial displays creating distinct effects of their own.

Hence the irregular appeals of Cinerama. Suppose we’re not interested in seeing the world as it registers on our sensory system. Suppose we’re interested in exploring uncommon pictorial effects. If we suppose all that, we can have the sort of fun watching Cinerama that we get from this 1877 picture by Caillebotte (Paris Street, Rainy Day), a virtuoso reworking of geometric space.

Take image sharpness. In the 2003 Bradford shows, I was overwhelmed by just how precisely distant objects registered. This was partly due to the greater resolution of a bigger image area, partly to the use of wide-angle lenses with breathtaking depth of field in brilliant sunlight. I can’t illustrate some of the most dazzling effects here, including the sight of a very distant bathing beauty racing through a crowd and up to the foreground in the Cypress Garden sequence of This Is Cinerama. But if you have a large home theatre monitor or projected display, you might be able to spot her. Here I’ll just mention how the farthest stretches of the famous roller-coaster stand out crisply, and in big-screen projection, the people in the far distance do too.

Such short-focal-length lenses distort the visual field in predictable ways. For one thing, they make horizontal lines bow upward or downward. For this reason, Cinerama DPs were at pains to keep the horizon near the center of the shot and to avoid or cover contours parallel to the horizon. Linus Rawling’s canoe oar bends disconcertingly in the central panel even before it hits the blend line and shoots off on its own.

Verticals can get distorted as well. On the edges of each panel, human figures can look bulged, pinched, or oddly torqued.

Cinerama’s triptych format complicates perspective effects by welding three wide-angle images together. When presenting built environments, often each panel displays its own distinct vanishing point–sometimes central, sometimes angular, sometimes both. The results recall the Caillebotte picture, all acute angles and avenues flung out to left and right.

One cinematographer tells us that “special sets had to be built with curves and bends to rectify the false perspective inherent in three-camera systems.” But often we get contorted interiors. Dr. Caligari might feel at home in Lowell Thomas’ office.

The blend lines add their own constraints. From a distance, the Golden Gate looks very planar, but as our plane swoops nearer, the horizon remains flat while the bridge develops a couple of kinks.

For staged action, veteran cinematographer William Daniels warned that “We invariably consider the blend lines first, then plot and stage the action to suit the camera setup.” Most obviously, directors had to keep people away from the panel joins. We can see the unfortunate result in this image from This Is Cinerama. The gent on the far right is at once pinched and bulged, and the building in the B and C panels gets the Caillebotte treatment. Worse, a young Venetian man’s head on the blend line undergoes an unfortunate warping.

When a figure moves from panel to panel, the wide-angle distortions combine with the panel edges to create a faceted, almost cubistic space. Here’s the first anomaly I spotted when watching How the West Was Won as a kid in 1963.

As Linus is walking toward Mr. Prescott, James Stewart seems to stride diagonally forward a bit (in the A panel). After he pivots, he grows very large as he starts to walk straight (the B panel). , then stride diagonally into depth (the third panel). Each wide-angle lens makes people swell or shrink as they come to or from the camera, and with the creases supplied by the blend lines, scenes like this become attractively odd. With the panels ironed out, we see people taking strangely roundabout paths to one another.

The effect is even more noticeable in big action scenes, when horizontal movements that are really parallel seem to peel off from one another. During the Indian chase, the wagons are fleeing alongside one another, as a back-projection shows. But the more dynamic angle on the wagon teams creates an image that hits you like a cold shower.

To the audience in front of a curved screen, the movement in the second shot would have looked somewhat (but not entirely, I think) more linear. For us, we see a perspective we’ve never seen before, with wagons diverging from one another but neither getting smaller or larger. And how about the dizzy swerve that the pathway in panel C takes when it reappears in panel A?

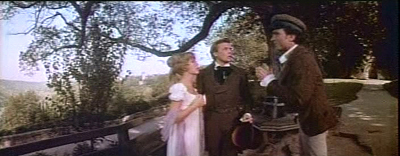

The angled-triptych format obliged actors to adjust their performances in counterintuitive ways. “An actor in a side panel,” wrote Daniels, “cannot look directly at one in the center panel when speaking to him, but must cheat a little–direct his eyes a little behind the one in the center.” Here’s an example from The Wonderful World of the Brothers Grimm that stands out when seen in the flat format. Wilhelm is speaking to Greta from the C panel, but it seems that Laurence Harvey didn’t cheat his body quite enough. He seems to be speaking past her, an effect not helped by the disproportionate size of his body.

This Is Cinerama is obsessed with centering its action, but sometimes the center seems strangely off-kilter. With the water-skiing women shown earlier, the three cameras create a sort of hollow viewing station. Why do the flanking skiiers seem to be moving at angles to the central trio? Why do the ropes of the central skiiers fly off (jaggedly) to one side, rather than expand directly towards us, like train tracks?

As with the wagon teams, you have to imagine diagonal actions as rotated inward to parallel one another during projection. What you see is not what you’d get in the theatre. But also, what you see is something you’ve never seen in a movie before.

Most of these effects are heightened by the inability of the three-eyed monster to record close-ups. Because of the short focal length, the camera unit sat very near the actors: for a shot from the waist up, the central lens was between one-and-a-half and three feet away. Putting the camera so close necessitated lights being attached to the camera unit. But normally close-ups were avoided, so the human figures never dominate their locales. These movies are, more than most, about space–however buckled and bizarre that space might be.

Because of the panels, panning shots were to be avoided, but certain kinds of camera movement forward were welcomed. The signature Cinerama shot is the shot plunging toward the vanishing point–a boat rushing through the water, an aerial view banking toward the horizon. Even though the blend lines made shapes and edges wrinkle, this gigantic, embracing image streaming toward viewers gave a compelling illusion that they were hurtling forward.

The distortions are less visible from a perfect vantage point in a Cinerama auditorium–presumably, as close as you can get. Distortions on the display edges would be minimized by peripheral vision, which isn’t good at registering detail. Presumably some of the curvilinear shapes, like Linus’ oar, and those kinks across the blend lines, would be less egregious if viewed straight on. Watching from the front row in Bradford, I recall seeing these distortions, but they didn’t seem as vivid.

Naturally, not everybody in the auditorium has a perfect vantage point. In the original screenings, people who had sat on the sides complained that movement on the nearest flanking panel seemed to flow upward. Smilebox, which respects the overall geometry of the display, still yields disparities. Linus’ oar still curves, though not as pronouncedly.

My images here, and yours on your home screen, are unavoidably mapping a curved display onto a flat surface, so there will still be anomalies. If you want to try cutting down on them, sit close to the Smilebox display. I prefer to sit back and enjoy their weirdness.

They’re features, not bugs

What about the films themselves? Arguably no great film was made in the format, but all the releases probably have some admirers. I want to end by talking about the two I find most appealing.

Cinerama’s travelogues were episodic, designed to show off features of the process in different filming situations. The two fiction features had to highlight the process and tell a coherent, engaging story. They too tend toward the episodic, but they handle that option in different ways. And stylistically, both work against the official “rules” of the new format.

The Wonderful World of the Brothers Grimm, an entertaining family film, employs a frame story. The brothers are assigned to write the family history of the local Duke. Jacob, an expert linguist, does his job dutifully, but Wilhelm plays hooky to find and write up fairy tales he hears. His zeal to collect stories leads to the loss of their commissioned manuscript, and he falls ill, during which several fairy-tale characters come to visit him. Eventually Jacob is honored by the Royal Academy, but it’s Wilhelm who gets enduring glory by being swarmed over by hordes of children anxious to hear his latest tale. Within this overarching plot, three of the stories are enacted using various special effects, including puppet animation. Some of these shots appear to have been shot in a non-Cinerama format and “paneled” afterward.)

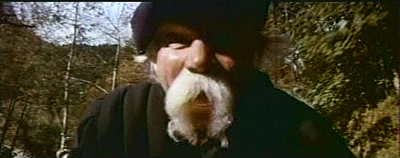

It’s tempting to ascribe the frame story’s direction to Hollywood veteran Henry Levin and the embedded fantasies to co-director George Pal. To the connoisseur of Cinerama, those fantasy passages offer some delights. If anybody told Pal about the rules for shooting in the format, he ignored them. The fairy tales give us whirling camera movements, bumpy subjective shots, and frequent assaults on the audience in the manner of 3D. During a wild coach ride, the coachman hurls himself to and from the camera. Later, a knight’s bumbling servant slays a dragon in lunging close-up.

You can even take certain passages as sly parodies of the brand. The Woodsman in the first tale has hitched a ride on the back of the coach, and he stoops to look underneath. Cut to his point-of-view: an upside-down version of a signature Cinerama shot.

Whoever directed the frame story scenes, however, was fairly bold too, moving his actors in zigzag patterns more flamboyant than the blocking of How the West Was Won. And instead of the small, high sets recommended for the format, Wonderful World shoots in throne rooms and palace salons that seem to stretch on forever. In smaller sets, like the brothers’ cottage, their friend’s bookshop, and especially the lair of a witch, the compositions take advantage of crannies and oddly angled planes that enhance the exaggerated distances.

As in German Expressionist cinema, the distortions seem to suit an atmosphere of fantasy. There’s even a massive violation of one of the basic rules of Cinerama: avoid tilting the camera. High and low angles were likely to exaggerate any distortions in the panels. Yet Levin, or Pal, or both occasionally throw in expressive angles, most strikingly a low angle showing Wilhelm’s family and friends ascending to his sickroom.

The Wonderful World of the Brothers Grimm solves the problem of the episode film by giving us a frame story. How the West Was Won solves it by a more threaded structure. A family saga creates branching stories that show three generations of kin participating in the winning of the frontier. The story acknowledges, briefly, the conquest of indigenous peoples–the “liberal Westerns” of the 1950s haven’t been ignored–but slavery doesn’t play a significant role. This is a story of white people.

The Prescott clan sets out on the Erie Canal, but on the rivers all but two of them lose their lives. The warm, slightly romantic Eve settles with the trapper Linus Rawlings on a farm in Ohio, while her sister Lilith ventures west. Eve’s son Zeb joins the Union forces in Civil War and later moves west with the railroad, eventually becoming a marshall. Lilith joins a wagon train, takes up with a gambler, inherits a worthless mine in California, and reunites with her lover on a riverboat. They become entrepreneurs investing in the railroad system. Near the end of the century, Lilith loses her fortune and joins Zeb, now retired, and his wife and children. But before they can settle down on Lilith’s inherited Arizona ranch, Zeb has to settle a score with a bandit who intends to rob a train. The film falls into sections specified in the credits–The Rivers, The Plains, and so on–but not in the film, though the parts usually end with fades.

Marker might note that How the West Was Won revives the piety and chauvinism on display in This Is Cinerama. The Prescott women found a kind of holy family, bound, as one song puts it, “for the Promised Land.” Some writers thumb through the phone book to get names for their characters, but screenwriter James R. Webb seems to have favored the Old Testament. Eve, living up to the positive side of her name, becomes the first woman of the new land. In forcing Linus to become a farmer, she helps turn the wilderness into a garden. Lilith, whose name associates her with sexuality and demonic possession, becomes a dance-hall girl and eventually a millionairess, but she has no children. At the end she returns to her nephew, Zebulon, named for her father; in the Old Testament he is the founder of a tribe. And Zeb has named his daughter Eve. The family abides in an endless cycle, its members replacing one another and its history intertwined with the full flowering of the United States.

The film ends with the sort of God’s-eye views that conclude This Is Cinerama, but emphasizing the modern West, with its dams, roads, cities, even whorls of traffic. Interestingly, in the place of the forward rush of the earlier film, these aerial shots pull us backward, the classic mark of the end of a story. But the finale of the epilogue carries us forward once more, under the Golden Gate Bridge and into a sunburst over the Pacific. Since women have played a central role, no surprise that the final lyrics of the choral accompaniment celebrate heroes as “every mother’s son.” This country has reached its natural limit; beyond is heaven, and the chorus tells us, here at last is the Promised Land.

Most scenes are handled briskly, but with little nuance beyond what the actors bring to the story. The spectacle remains appealing, the music infectious, and the imagery always impressive–especially when it’s a little whacked out, as in my examples above and many other scenes of the film. Like The Wonderful World of the Brothers Grimm, this has shown that Cinerama can be edited rapidly. This Is Cinerama has only a little more than two hundred shots, but Wonderful World has a thousand, and How the West Was Won has over eleven hundred. The chapters of the latter yield some striking results: most average between eight and nine seconds, but John Ford’s Civil War segment averages nearly fifteen seconds, while the climactic Outlaws segment averages about five seconds.

That climactic sequence, directed like most of the film, by Henry Hathaway, makes splendid and varied use of the format. Despite a heavy reliance on back projection and several shots that seem not to have been made in the three-camera process, this monumental remake of The Great Train Robbery is a showcase for how Cinerama could create exciting action through staging and editing. To the advantages of Cinerama–forward drive, looming landscapes, and immersive sound–Hathaway and editor Harold Kress add percussive cuts of logs sliding this way and that, along with painful stunts, including one showing a man flung off a train and into a cactus.

By contrast, the Civil War sequence shows how a director can triumph over an inflexible format by relying on expressive stasis. Ford the pictorialist will carve striking compositions out of the constraints of Cinerama. He exploits the depth of the 27mm lenses, sometimes stationing all his figures in the central zone, as if he’s trying to preserve the 1.37 aspect ratio. At other moments he confines the action to a single flanking panel.

Sometimes Ford simply ignores the triptych format in order to split the frame in half or, say, two-fifths. He also gives his actors postures, props, and gestures that allow them to underplay. With Ford, even fresh-minted junior stars like Carroll Baker and George Peppard can give performances of gravity.

Ford’s creative choices stand out most strongly in two scenes set on the farm. In the first, Linus Rawlings has gone off to battle, and his son Zeb is itching to follow. Eve, now old, accepts with weary sadness that he will have his way. There’s a Griffithian two shot of Eve and Zeb on the porch, her arms dangling wearily and her right hand rising and falling as she asks Zeb about whether he’ll get a uniform. The hell with Cinerama, Pappy seems to say: Just fill up half the frame with the cabin to keep us fastened on the couple.

After a quick embrace, Eve dashes into the house. A porch shot that is virtually a Fordian doorway framing shows Zeb leaping with joy before he turns, sees something in the house, and halts in his tracks. Ford needn’t show us Eve’s grief. This is the most tactful shot in the whole film.

Soon enough Ford will recall this scene. Zeb has left for the war. Eve, kneeling at the family plot, prays to her father before slipping behind the rail. Her face is hidden, but her hands again express her resignation, and prefigure her death. She was never the same, her other son will say, after Zeb left.

These homestead passages are echoed by a scene at the end of the Civil War segment. Back from the war, Zeb learns of his mother’s death from his brother Jeremiah. The two sit on the porch sharing a dipper of water and recalling their father. Zeb rises to go, they shake hands, and we get another muted Fordian moment. Why move your actors when you can pose them?

Now the old director, a master of depth since the 1910s, bends this newfangled format to his own ends. Zeb leaves the frame, comes back in the far distance, and is finally blocked by the farmhouse, leaving Jeremiah quietly weeping.

That’s how you handle this busy, noisy new contraption, Ford seems to say. Dwell on moments of stillness and pathos. Use handshakes, embraces, a drooping black shawl. Keep the action in a well-defined zone. And treat this as a silent movie.

The most comprehensive account of Cinerama’s development is Thomas Erffmaier’s 1985 Northwestern Ph. D. thesis, The History of Cinerama: A Study of Technological Innovation and Industrial Management. Also invaluable are John Belton’s Widescreen Cinema (Harvard University Press, 1992) and Robert E. Carr and R. M. Hayes’ Wide Screen Movies (McFarland, 1988), usefully supplemented by Daniel J. Sherlock’s emendations here. A good older work is Michael Z. Wysotsky, Wide-Screen Cinema and Stereophonic Sound (Focal Press, 1971). Sheldon Hall and Steve Neale put This Is Cinerama into the context of postwar blockbusters in Epics, Spectacles, and Blockbusters: A Hollywood History (Wayne State University Press, 2010), Chapter 7. On the Web, restorer and cinematographer Greg Kimble provides a thorough and well-illustrated account of Cinerama at In 70mm.

Chris Marker’s “Le Cinérama” appeared in Cahiers du cinéma no. 27 (October 1953): 34-37.

Cinerama grew out of Fred Waller’s experiments with gunnery-training displays during World War II, as Strohmaier documents in Cinerama Adventure. Waller discusses this work in “Cinerama Goes to War,” New Screen Techniques, ed. Martin Quigley, jr. (Quigley, 1953), 119-126. This collection includes other pieces of value on Cinerama, 3D, CinemaScope, and other new technologies. It would be interesting to know if Waller’s efforts influenced, or were influenced by, psychologist J. J. Gibson’s comparable wartime experiments with aerial training films. Gibson’s ideas about how we grasp space through “optical flow” and centered perspective have obvious parallels with the Cinerama process. Waller was said to have been influenced by another psychologist, Adelbert Ames, Jr., one of the founders of 1950s “New Look” psychology. Waller’s belief that our peripheral vision was more important than stereopsis in determining depth echoes Ames’ hypothesis that convergence and binocular disparity were overrated as depth cues.

Greg Kimble provides a thorough overview of the making of How the West Was Won in a 1983 article for American Cinematographer, available here. I’ve drawn as well on William Daniels’ article “Cinerama Goes Dramatic,” American Cinematographer 43, 1 (January 1962): 28-29, 50-54. Also useful was Darrin Scott, “Panavision’s Progress,” American Cinematographer 41, 5 (May 1960): 302, 304, 320-322, 324. My quotation about readjusted sets comes from Scott’s piece.

Three-panel Cinerama features can be seen occasionally today at the Pictureville Cinema in Bradford, the Cinerama Dome in Los Angeles, and the Seattle Cinerama.

Simultaneously with This Is Cinerama, Flicker Alley has published a lavish Smilebox version of Windjammer, also prepared by David Strohmaier. That’s a whole other story.

P.S. 5 October: You never can tell. Jim Emerson forwards me this Indiewire report by Len Maltin on a new short made in three-panel Cinerama.

How the West Was Won.

John Ford and the CITIZEN KANE assumption

Kristin here:

A few days ago I was reading the February 24 issue of Entertainment Weekly. I started subscribing to EW during the days when I was working on The Frodo Franchise. Being a Time Warner publication, it tended to feature The Lord of the Rings a lot (Time Warner also owns New Line Cinema). I was trying to keep track of the popular-press coverage of the film, and EW was a helpful source. It also used to be a bit more substantive in those days. In recent years it has become more fluffy. Still, it’s handy for reading over lunch or when brushing one’s teeth.

Turning to page 66, I found Chris Nashawaty’s “The Most Overrated Best Picture Winners.” The double-page spread was slathered with photos of My Fair Lady, Out of Africa, Gandhi, The King’s Speech, and Shakespeare in Love. (The piece is online, but as a gallery rather than an article, lacking the introduction.)

I like putdowns of overrated and/or over-rewarded films as much as anyone, so I settled in to read. I was shocked, however, to find that the first film on the list was How Green Was My Valley.

I happen to think the How Green is one of the very greatest American films. Probably no Best Picture winner in the history of the Oscars has been a more fitting recipient of that award. Why lump it in with Shakespeare in Love?! (I think you know what’s coming.)

Nashawaty gives his reasons. He admits that How Green has three pluses going for it: “It’s got beautiful cinematography, John Ford as a director, and a three-hankie plot about a Welsh mining village.” He goes on: “The minuses: mismatched accents and the still-outrageous fact that it beat Citizen Kane.”

Mismatched accents as a reason not to win Best Picture? The notion belittles the brilliant ensemble acting in Ford’s film, with Donald Crisp, Sarah Allgood, Barry Fitzgerald, Maureen O’Hara, Walter Pigeon, and many others giving fabulous performances, career bests in some cases. It is a joy to watch them interact. Of course most of these people sound more Irish than Welsh, but frankly, who cares?

By the way, I’m assuming Nashawaty means the mismatch of Irish accents to a Welsh setting, not a miscellany of accents among the cast, which is common in Hollywood films. Besides, isn’t accuracy of accents—think Meryl Streep—one of the criteria used to judge the very Oscar-winners that Nashawaty is decrying? I’ve never seen Gandhi, but I’ll bet Ben Kingsley did a heck of an authentic accent. Accents are one of the easiest aspects of performances to notice, so it’s not surprising that they are so often a factor in Oscar-nominated and -winning roles.

But it’s not really the accents that bother people about How Green. No, it’s really the “beat Citizen Kane” part that grates on film fans. Quite possibly it has led them to dismiss or undervalue one of Ford’s greatest films.

I’m going to be heretical and say that How Green deserved to win over Kane.

For years Kane has been sitting atop many lists of the greatest films of all times, including polls of professional film critics. The notion that Kane really is the greatest film of all time has become so engrained that people seem seldom to question it. Back when that idea arose, critics were unaware of the films of Yasujiro Ozu, probably the world’s greatest film director to date. Play Time was for years ignored and only recently has begun to be recognized for the masterpiece it is. With the rise of film restoration in the 1970s and the spread of film festivals and retrospectives, we now know vastly more about world cinema than we did before. Yet Kane has settled into its top slot for many people, including entertainment journalists. I can think of many films I would rank above Kane.

No doubt it’s a great film, with a marvelously tricky plot, another great ensemble of actors, splendidly distinctive cinematography, and innovative special effects masquerading as cinematography. It was hugely influential at the time and remains so to this day. Of course, Welles has declared time and again that he learned filmmaking by watching Stagecoach over and over, so Kane would probably not be as good as it is without Ford’s influence. Not that such influence proves that How Green is better than Kane, but it shows Welles’s respect for Ford. More on that below.

Middlebrow and proud of it

I think another reason why How Green tends to be dismissed as merely the film that cheated Kane out of its best-picture Oscar is that it is resolutely middlebrow. Indeed, in that way it fits in with all the other films Nashawaty writes about. They’re all resolutely middlebrow, too. Middlebrow films are for those people who look down upon popular genres and want to feel they’re seeing something worthwhile.

Despite this attitude, most of the great American films fit into popular genres: Keaton’s The General (or substitute your favorite Keaton film), Kelly and Donen’s Singin’ in the Rain, and Hitchcock’s Rear Window (or, if you will, Shadow of a Doubt or Notorious or Psycho). This is one thing that the auteur theory, somewhat indirectly, taught us. Howard Hawks’s modern reputation rests partly on his ability to waltz into any American genre and make one of its best entries. The Godfather is technically a gangster film, but one could argue that by taking it from a bestseller and making it into a glossy A picture, Coppola pushed his film into the middlebrow range far enough for the Academy to dub it Best Picture—twice. The one Best-Picture winner of recent decades that arguably did thoroughly deserve the prize was a serial-killer thriller, The Silence of the Lambs. I think a lot of people were surprised that the strait-laced Academy members could accept such subject matter in a nominee, let alone a winner.

Like Hawks, Ford moved easily among genres and excelled at least once in every one he touched. He made arguably the greatest war film ever, the underrated They Were Expendable, and the greatest Western, The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (or Stagecoach or My Darling Clementine). He also pulled the turgid middlebrow genre of the 1930s biopic into greatness with Young Mister Lincoln. There’s no doubt that Ford was an uneven director, and arguably his worst films arose from his attempts to go for middlebrow respectability. The Fugitive is almost unwatchable in its pretentiousness, and the mid-1930s brought forth such items as Mary of Scotland and The Informer. But starting in 1939, he produced an almost unbroken string of masterpieces and near masterpieces, culminating in They Were Expendable and My Darling Clementine.

We should recall also that Welles himself adapted a middlebrow bestseller for the film he made directly after Kane: The Magnificent Ambersons. Had the studio not meddled so extensively with it, it probably would have been one of the American cinema’s great middlebrow classics, fit to sit alongside How Green.

Earned sentimentality

Welles himself probably would have felt honored by that comparison. In a 1967 interview he described his taste in films:

Old masters—by which I mean John Ford, John Ford, and John Ford. With Ford at his best, you feel that the movie has lived and breathed in a real world—even though it may have been written by Mother Machree.

In other words, Welles recognized that sentiment did not take away from the brilliance of Ford’s best work, and How Green is definitely in that category. Welles was too big an egotist not to have been annoyed at losing the Best Picture award to Ford, but he probably understood why How Green won better than most people do today. Today, apart from groups of women who go to see heartwarming female-oriented fare, audiences tend to shy away from sentimentality.

To his credit, Nashawaty lists sentimentality as a plus for How Green. (“Three-hankie plot” has a dismissive ring to it, but I’ll chalk that up to the requirements of infotainment journalese.) But I’m sure that many people who underrate How Green do so because it’s essentially a family melodrama where everything starts out in an Edenic state and the situation slowly goes downhill to a distinctly unhappy ending for all concerned. A lot of people simply dismiss sentimentality in all its manifestations, presumably as too naive, hitting us below the belt for an easy emotional appeal. In this day and age, it is much easier to admire cynicism than unembarrassed emotion. Despite its subject matter of environmental depredation by greedy companies, How Green is resolutely focused on the joys and sorrows of the family. Kane is cynical in a very modern way. Yet I cannot believe that we care nearly as much about the characters in Kane, even Susan, as we do in How Green.

Sentimentality is not a bad thing in itself. Sure, it’s an easy thing to evoke. Easy sentimentality is banal and cloying because there’s so little underpinning it except conventional romance and cute babies and long-suffering mothers and the like. Then there is what I call earned sentimentality. (A similar distinction is often made between sentiment and sentimentality.) Films with this quality are rich with original characters and situations that might make even a viewer who dismisses easy sentimentality pull out a hankie. The sentimentality in Chaplin’s films sometimes achieves this, and his Little Tramp character has been widely praised over the decades for his mastery of this emotion. Even those who dismiss sentimentality can forgive Chaplin, since humor usually undercuts the cloying quality just a bit. In a less obvious way, Harold Lloyd sometimes proves himself a master of sentimentality, as in The Kid Brother. And earned sentiment is not dead. It pervades Big Fish, another film that has been underrated or at least largely forgotten, perhaps in part due to its sentimentality. It has eccentrics galore and an original plot idea, but it doesn’t have that edgy, weird quality that sophisticated viewers treasure in Tim Burton’s work. There’s even sentimentality in the Wallace & Gromit films, though again humor makes the emotion palatable. Art cinema has its own sentimental masterpieces: Bicycle Thieves, Jules et Jim, Tokyo Story, Sansho the Bailiff, Distant Voices, Still Lives, and the list could go on and on. True, all these films are grimmer in part or in whole than the average Hollywood film, but so is How Green.

By the way, Welles himself delivers one of the sublime sentimental passages of world literature in the heartbreakingly nostalgic “chimes at midnight” speech in Falstaff, which has other passages of the same emotion. The Magnificent Ambersons is a sentimental film of a different sort.

For my money, How Green earns its sentimentality as well as any film ever made.

On everyone’s syllabus

You may be asking at this point, if How Green is so fantastic, why didn’t Bordwell and Thompson use it as their central example of a narrative film in Film Art? Why is Kane in that spot? There’s a simple answer to that: Kane is a very teachable film, and How Green, to say the least, is not. Our challenge was to find a film that most teachers used, or would happily start to use, and that demonstrated many concepts about film narrative and style that we wanted to describe.

Some films are just more teachable than others. They use a lot of different techniques, both stylistic and formal, in a way that students can notice. Hitchcock is probably the most teachable director overall, and I would bet that his films show up on introductory-film-class syllabi more often than any other director’s. It’s just that with Hitchcock, there’s no one film that’s self-evidently more useful for teachers than others. I sometimes think that one could almost write an entire introductory textbook using nothing but examples from Lang’s M. There are other classics like that. But Kane beats them all: a complex but clear flashback structure, obvious and varied technique, a complex soundtrack born of Welles’s radio experience, and examples of many things teachers want their students to learn about. It’s a classical Hollywood film, but it has touches of art-cinema ambiguity about it. It’s entertaining, at least to motivated students, so they’re likely to pay attention rather than dismissing it. They may come into the class knowing that it’s a revered classic and hence be interested in seeing it. It may even reconcile them to watching black-and-white films.

How Green, however, is difficult to teach. David has found this to be true. Our colleague Lea Jacobs occasionally offers a seminar on Ford, and How Green is among the most challenging films by a director whom students tend to be slow to warm up to. She attributes this partly to changing tastes and partly to the subtlety of the style of its cinematography. It’s very hard to make students, and indeed almost anyone who isn’t already a believer, see why How Green is a masterpiece.

Kane is not only teachable, but it’s highly conducive to analysis, and no doubt these two traits are closely related. David’s first widely seen article was a study of Kane, and I wrote the sections of chapters in Film Art dealing with it. I don’t mean that it’s simple; Kane is a complex film that has provided material for many different essays and books. But How Green has so many ineffable qualities that it resists cold, precise analysis. It has been one of my favorite films for over three decades, and occasionally I have contemplated writing something in-depth about it. I can’t, however, think what one could possibly write. One would just have to throw up one’s hands and say, “You either get it or you don’t.”

It reminds me of when I was nearing the end of my undergraduate career. I didn’t “get” Godard. I found his work pretentious and boring. But given how many people whose opinions I respected admired Godard, I persisted. I think I suffered through seven features, and at about number eight (Weekend), I got Godard. Maybe Ford, at least for his non-Western films, is somewhat the same sort of challenge. I’ve written analyses of two of Godard’s more difficult films, Tout va bien and Sauve qui peut (la vie). I’m still scared to try to deal with How Green.

(Stagecoach is much easier. For several editions of Film Art we included an analysis of it, which I wrote. Eventually it got replaced, but it’s still available here.)

A few hints

Since I doubt I will ever thoroughly analyze How Green, here I’ll offer just a few hints as to why it deserved to take home Best Picture and leave Kane an also-ran.

Nashawaty mentions the beautiful cinematography. Arthur C. Miller was 20th Century-Fox’s A-list cinematographer, having shot some of the Shirley Temple films in the 1930s, films that kept the studio afloat during the Depression. He teamed with Ford only on Tobacco Road and How Green, though he apparently helped with Young Mr. Lincoln uncredited. Miller won his first Oscar for How Green, his second for Henry King’s The Song of Bernadette (the main virtue of which is it looks a lot like How Green), and his third for Anna and the King of Siam. Few of Miller’s non-Ford films like The Ox-Bow Incident and Gentlemen’s Agreement are watched much today. He did lens somewhat minor films by major directors (Hitchcock’s Lifeboat, Preminger’s Whirlpool), but he is less famous than he deserves.

Just a few examples. How Green contains some of the same techniques that are so admired in Kane, but in a less flamboyant fashion. Deep focus, for example:

Admittedly, the people at the right rear are slightly out of focus, but the shot was done in-camera. No special effects.

The interiors of How Green have a distinctive touch: patches of light on the ceilings. Implausible, when you start to think about where the light must be coming from, but beautiful nonetheless. Miller (or at least Fox) almost had a patent on this way of lighting a room. With Kane getting so much credit for adding ceilings to sets, we should remember that Ford has done so in Stagecoach and does it here as well. It’s not as in-your-face as Kane’s ceilings, but it’s an example of the subtlety that pervades How Green. The first shot (below) is part of the series of scenes at the beginning setting up the happy home life of the large and relatively prosperous Morgan family; the father is about to dole out allowances to his sons on payday. The second comes much later, as the last two grown sons prepare to depart abroad in search of work after the mine has declined.

Kane is admired for both its long takes and its dynamic editing. Ford seldom used either. He held a shot long enough to be effective but not long enough to turn into showing-off. Take the scene after Angharad’s marriage to the wealthy mine-owner’s son. Mr. Gruffydd, the minister whom she actually loves, has performed the ceremony. As has been pointed out many times, Ford filmed the final shot without doing any close views to be cut in later. (Indeed, most of How Green was edited in the camera by Ford, so that most of the footage he shot ended up on the final version. It was his way of keeping control over his film.) By happy accident, a breeze caught Angharad’s veil, sending it soaring and twisting through the shot. Perhaps it was a reflex gesture on the part of the actor playing the mine-owner’s son, but he reaches out and holds the veil down as his bride climbs into the coach; it perfectly captures his cold, proper nature. For a split second before the coach pulls away out right, Angharad glances back toward the church, where Gruffydd remains inside. Once the coach is gone, Ford holds, and Gruffydd appears on the hillside at the rear, watching and then turning to go inside. No cut-in mars the perfection of the shot.

There’s one of the hankie moments. I get tears in my eyes during this scene, partly out of sympathy of the sundered couple and partly from aesthetic pleasure. If ever there was a single shot that exemplifies Ford’s combination of sentiment and discretion, this is it.

The last of these five frames belongs to the visual motif that appears in the opening sequence, as Angharad waves to her father and Huw on the beautiful distant hillside (see above), as well as in the final scene, where Angharad struggles in her fine clothes across a similar hillside, swathed in smoke, to reach the mine after the disaster that traps her father (see below). Such moments create a quiet measure of the gradual degradation of the valley and the dwindling of the family’s happiness.

Did Ford realize how brilliant this shot was? We can be confident that Welles was well aware of how daring and wonderful his techniques in Kane were. It shows in the film. With Ford, one can only suspect that he knew exactly what he had accomplished here and elsewhere.

Another thing How Green shares with Kane is a flashback structure. It largely consists of one big flashback told by the protagonist, not a series of embedded stories by witnesses. Nevertheless it’s unusual, since we never come out of the flashback. The tale opens with the valley in severe decline, the village nearly deserted, and the hero about to depart for a better life. We witness the decline of his family as he grows, gets educated, and opts to follow his father and brothers into a job in the mine. By the end his elder brothers have scattered all over the world, his father is dead, and we don’t know what has become of his mother and sister. (One plausible assumption is that his mother has recently died, prompting his departure in the opening scene.) Yet the ending gives us a series of shots of the family as they had been in their prime, with the protagonist-narrator declaring, “Men like my father can never die.” Like Kane, it is a film about the power of memory, but in this case the power to comfort rather than to baffle.

One thing that makes How Green stand apart from some of Ford’s other films is that it for once controls the director’s penchant for mixing in broad humor. His stable of supporting actors playing minor characters who love to drink and fight can be trying. There is a particularly ill-advised moment in The Searchers when, after the epiphanic moment when Ethan has lifted Debbie as if to kill her and then embraced her, Ford cuts to the Ward Bond character having a wound on his posterior dressed, to the derision of his comrades. That Ford should undercut such a scene with a vulgar moment of comedy combines with another flaw or two in the film keep if off my list of Ford’s very best films. And much though I love the first three-quarters of The Quiet Man, that climactic brawl just goes on and on.

In How Green, the characters Dai Bando and Cyfartha provide humor, but they are held in check. They play reasonably significant roles in the action, helping Huw deal with the school bullies and his sadistic teacher. Many of the family scenes involve amusing moments as well, moments that arise naturally from the situations and have no air of mere comic relief. In screenwriter Philip Dunne’s introduction to the published version of his screenplay, he finds fault with several scenes and actors. Maybe he’s right that the scene when the mine owner visits the Morgan family is played for broad comedy, but it’s not as broad as elsewhere in Ford’s work. Luckily Ford’s brother Francis does not return for yet another of his bit parts as a drunk.

In 1972, when Ford was dying of cancer, the Directors Guild held an evening gathering to honor him. He was asked to choose one of his films to be projected, and he named How Green. He had consistently said he considered it his finest film.

There’s no budging Kane

I doubt that the notion of Citizen Kane as the Greatest Film of All Time will go away anytime soon. Changing (and unchanging) tastes are reflected in the decadal Sight & Sound poll of critics concerning the ten greatest films of all times. They started in 1952 and have continued to 2002, with another due this year. The lists reflect the fact that apparently critics can somewhat agree on the greatest older classic, though fashions in these come and go, but they cannot agree on much of anything that has been made since 1970:

1952

- 1. Bicycle Thieves (De Sica)

- 2. City Lights (Chaplin)

- 2. The Gold Rush (Chaplin)

- 4. Battleship Potemkin (Eisenstein)

- 5. Intolerance (Griffith)

- 5. Louisiana Story (Flaherty)

- 7. Greed (von Stroheim)

- 7. Le Jour se lève (Carné)

- 7. The Passion of Joan of Arc (Dreyer)

- 10. Brief Encounter (Lean)

- 10. La Règle du jeu (Renoir)

1962

- 1. Citizen Kane (Welles)

- 2. L’avventura (Antonioni)

- 3. La Règle du jeu (Renoir)

- 4. Greed (von Stroheim)

- 4. Ugetsu Monogatari (Mizoguchi)

- 6. Battleship Potemkin (Eisenstein)

- 7. Bicycle Thieves (De Sica)

- 7. Ivan the Terrible (Eisenstein)

- 9. La terra trema (Visconti)

- 10. L’Atalante (Vigo)

1972

- 1. Citizen Kane (Welles)

- 2. La Règle du jeu (Renoir)

- 3. Battleship Potemkin (Eisenstein)

- 4. 8½ (Fellini)

- 5. L’avventura (Antonioni)

- 5. Persona (Bergman)

- 7. The Passion of Joan of Arc (Dreyer)

- 8. The General (Keaton)

- 8. The Magnificent Ambersons (Welles)

- 10. Ugetsu Monogatari (Mizoguchi)

- 10. Wild Strawberries (Bergman)

1982

- 1. Citizen Kane (Welles)

- 2. La Règle du jeu (Renoir)

- 3. Seven Samurai (Kurosawa)

- 3. Singin’ in the Rain (Kelly, Donen)

- 5. 8½ (Fellini)

- 6. Battleship Potemkin (Eisenstein)

- 7. L’avventura (Antonioni)

- 7. The Magnificent Ambersons (Welles)

- 7. Vertigo (Hitchcock)

- 10. The General (Keaton)

- 10. The Searchers (Ford)

1992

- 1. Citizen Kane (Welles)

- 2. La Regle du Jeu (Renoir)

- 3. Tokyo Story (Ozu)

- 4. Vertigo (Hitchcock)

- 5. The Searchers (Ford)

- 6. L’Atalante (Vigo)

- 6. The Passion of Joan of Arc (Dreyer)

- 6. Pather Panchali (Ray)

- 6. Battleship Potemkin (Eisenstein)

- 10. 2001: A Space Odyssey (Kubrick)

2002

- 1. Citizen Kane (Welles)

- 2. Vertigo (Hitchcock)

- 3. La Regle du Jeu (Renoir)

- 4. The Godfather, parts I and II (Coppola)

- 5. Tokyo Story (Ozu)

- 6. 2001: A Space Odyssey (Kubrick)

- 7. Battleship Potemkin (Eisenstein)

- 7. Sunrise (Murnau)

- 9. 8 ½ (Fellini)

- 10. Singin’ in the Rain (Kelly and Donen)

There is much that could be said about these lists. Most readers will probably be astonished to see Bicycle Thieves at the head of the first list, with Kane not even present. Brief Encounter above La Regle du jeu. Louisiana Story, of all things, and Le Jour se léve. By 1962, tastes had changed. Italians won the day, with three films, while Eisenstein, whose Ivan the Terrible, Part 2 had finally been released in 1957, had two films chosen. Two French films and two American. But it was in this year that Kane appeared, immediately bouncing to number one, a position from which it has never budged. I suspect it will sit atop the 2012 list, simply because now so many critics assume it’s the best film ever–and even if they don’t assume that, they won’t be able to agree on an alternative.

Ford has had only one film on the lists, The Searchers, in 1982 and 1992. For a time it was the Ford film du jour, until in 1992 Hitchcock zipped past it with Vertigo, which settled into the second spot after Kane in 2002. Mizoguchi has been on only one list, in 1972 with Ugetsu Monogatari. Ozu’s first film to became well known in the west didn’t make the list until decades later, in 1992, and yet despite the discovery of Late Spring and Early Summer and An Autumn Afternoon, Tokyo Story remains the Ozu film. Tati has never appeared on the list. Neither has Bresson. I’ll buy the idea that critics are out there voting for Bresson like mad, but all for different films. But Play Time, surely one of the very greatest films ever made, should be easy to converge around. Finally, the only post-1970 film on here (and not by much) is the Godfather pair. I was still working on my master’s degree when the first one came out.

I suppose by now, with so many smaller countries starting to make movies and so many festivals making them widely available, it becomes impossible to anoint new classics in the way critics used to. Kiarostami’s Koker Trilogy, in whole or in part, would seem to be such a classic, but there are so many great competing films. Does one have enough perspective to choose more recent films when others, like Sunrise, have stood the test of time? Play Time is 45 years old now, and I think it’s a greater film than most of those on the 2002 list–certainly including the number one. Possibly it will make the list this year.

Why is Kane so fixed at the top, when other films move up and down and ladder, and some appear and disappear? Perhaps the simple assumption that if it has been up there so long, it must really be the greatest film ever made.

I think this business of polls and lists for the greatest films of all times would be much more interesting if each film could only appear once. Having gained the honor of being on the list, each title could be retired, and a whole new set concocted ten years later. The point of such lists, if there is one, is presumably to introduce people who are interested in good films to new ones they may not have seen or even known about.

Such an approach is not wholly unthinkable. Each year the National Film Registry maintained by the Library of Congress chooses 25 films deemed to be national treasures worthy of special priority in preservation. There’s probably some assumption that the best films were on the early lists and that each new 25, especially coming annually rather than at longer intervals, must be of less interest than its predecessors. But on the whole it’s a pretty egalitarian exercise, one that treats all kinds of films as fair game, not just fiction features, and it really does draw attention to obscure films that deserve to be better known. Given how many films have been made in the USA, it will be a long time before the Registry is scraping the bottom of the cinematic barrel. The entire world could supply so many more.

At any rate, I don’t insist that justice will not be done until How Green or some comparable Ford masterpiece appears on Sight & Sound‘s poll, any more than I would say that it’s having won the Best Picture Oscar proves that it’s a great film. I think we all know that the whims of the Academy members are hard to fathom, then and perhaps even more so now. But why call it overrated just because it beat Kane for that dubious honor? If anything, How Green is underrated for that very reason. Had it been made in a different year and won the Oscar against some other films that weren’t Kane, would it be any better or worse?

If you have never seen How Green and are not wholly opposed to earned sentimentality, give it a try. Just make sure you have at least three hankies handy.

PS March 8, 2012. Our friend Antti Alanen points out that Maureen O’Hara said the shot with the veil was carefully planned. She disagrees with Philip Dunne’s claim that the wind catching it was a happy accident, as Joseph McBride recounts in Searching for John Ford:

Dunne thought Ford had “one of the greatest strokes of luck a director ever had” when the wedding veil suddenly caught a gust of wind and billowed behind Mareen O’Hara as she walked down the steps from the church. O’Hara recalled, “Everybody said, ‘Oh, that Ford luck! How wonderful that was! What an effect it has!’ Rubbish! It wasn’t ‘Ford luck.’ It was three wind machines placed by John Ford, and I had to walk up and down those steps many times while he worked out that the wind machine would do exactly that.” As she climbs into the carriage, the ator playing her husband, Marten Lamont, reaches out to catch her veil. Dunne thought, “The man shouldn’t have touched it when the veil spiraled up. My God, what a shot! Luckily, Joe LaShelle, who was the operator, just gave it a little tilt with the camera.” I told Dunne I thought the gesture of restraining the veil (probably planned by Ford, like the rest of this meticulously composed shot) is an eloquent metaphor for the repressiveness of Angharad’s loveless marriage. “Well, I guess so,” the screenwriter responded. “I didn’t think beyond that. I said, ‘My God, you get a break like that, you leave it alone.'” (p. 332)

PPS March 11, 2012. Thanks to Przemek Kantyka for pointing out that Ugetsu actually figured on the 1962 and 1972 lists.

Silents nights: DVD stocking-stuffers for those long winter evenings

Von Morgens bis Mitternachts

Kristin here:

The year 2011 has been a good year for silent cinema on DVD. In time for the holiday shopping season, here’s an overview of some of the highlights.

One-stop shopping for the latest restorations

In the past we have recommended films released on DVD through the Munich Film Museum’s Edition Filmmuseum. We haven’t really emphasized enough, however, what a major resource this site is for film enthusiasts interested in restorations of older films and new editions of hard-to-see modern films (like the work of James Benning). Edition Filmmuseum sells not only its own impressive series of releases but also DVD editions of restorations by other major national European archives. Its website is available in German and English versions, and it is as easy to sign up and order DVDs there as it is through Amazon. The DVDs on offer can be browsed via a number of different categories, such as “Silent films,” “German movies,” and “Danish classics.” Releases from Lobster Films and Flicker Alley are also available through Edition Filmmuseum. Have a look at its forthcoming releases here. North American educational institutions seeking public performance rights for many of these and other titles should contact Gartenberg Media Entertainment.

Scandinavia comes on strong

Danish and Swedish films show up fairly regularly on DVD these days, but Norwegian films are rarities. This year, though, there are two of them.

The Danish Film Institute continues to release the films of Carl Theodor Dreyer. This time it’s a pairing of Elsker Hverandre (Love One Another, 1922) and Glomdalsbruden (The Bride of Glomdal, 1926), also available in Blu-ray. (See below.) I have to admit that these are not among my favorite Dreyer films, and I don’t think many would put them alongside his best works. Still, Dreyer is one of the great masters of world cinema, and anyone seriously interested in film history will want to see these. Back when David was working on his book on Dreyer, we went to Copenhagen and saw these at the Film Institute. They were incredibly rare, and it was a privilege to see them. Now, they’re available to all. Check out the Institute’s entire list of restored Danish classics on DVD here.

[Dec. 16: Archivist Jan-Christopher Horak has recently blogged about Elsker Hverandre.]

The Bride of Glomdal is the first of our two Norwegian features. Dreyer worked outside Denmark a number of times. In the summer of 1925 he shot this film in Norway. His next film was to be La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc.

The second is Laila, a 1929 Norwegian feature, also with a Dreyer connection. Its director, George Schéevoigt, had been Dreyer’s  cinematographer for some of his early films: Leaves from Satan’s Book, The Parson’s Widow, Once Upon a Time, and Master of the House. Laila bears no sign of Dreyer’s influence, but its images, shot in the snowy mountains and valleys of the arctic regions of Norway, are gorgeous.

cinematographer for some of his early films: Leaves from Satan’s Book, The Parson’s Widow, Once Upon a Time, and Master of the House. Laila bears no sign of Dreyer’s influence, but its images, shot in the snowy mountains and valleys of the arctic regions of Norway, are gorgeous.

Like many features made in countries with no real established film industry (Laila’s footage had to be processed and edited in Copenhagen), Laila exploits both national literature and landscapes to distinguish itself from the Hollywood films that dominated European theaters. It was based on an 1881 novel by J. A Friis, Fra Minmarken, Skildringer. Friis strove to promote the rights of the indigenous Sami people (sometimes known as Lapps). The story follows the heroine, Laila, from infancy to adulthood. The first half of the film succeeds in giving a distinctly non-classical feel to the story. Laila is lost in the snowy wastes when wolves attack her family as they travel on sleds. She is found and nurtured by a childless Sami couple who come to love her but return her to her parents when they learn her background. The scene of the return is handled in a subtle and moving fashion. As the grieving parents console each other on Christmas Eve, Aslag, the baby’s foster father, enters at the left, with the tree blocking the door. He crosses to appear at the center and puts the child beside the presents under the tree:

A cut-in to Aslag shows him struggling with his emotions before turning to the parents and declaring, “Tonight all should be happy.” The mystified parents stare at him uncomprehendingly before he explains that he had found their daughter:

Once Laila grows up, the film turns into the more typical romantic triangle. Still, its epic landscapes and focus on a little-known ethnic group make it quite appealing, and the print itself is gorgeous. Flicker Alley has provided a rare opportunity to step outside the more familiar filmmaking countries and explore a bit. Our friend, the fine Danish film historian Casper Tyberg, has provided a helpful text in the accompanying booklet.

Casper also provides a commentary for The Criterion Collection’s release of the restored version of Victor Sjöström’s The Phantom Chariot. (It’s number 579 for you Criterion completists–but you already know about this disc anyway.) I won’t say much about it, since it will inevitably show up in our year-end list of the ten best films of 1921. Here I’ll just note that it’s also a beautiful print, with impeccable tinting and toning that don’t darken the images to the point where the composition is obscured–something I’ve seen too often in recent DVD releases of silent films. The frame above shows the opening scene, with its masterful control of lighting. I was disappointed that the supplements stress Sjöström’s influence on Ingmar Bergman. It may sound heretical, but Sjöström seems to me the better director, and I wish there had been more on his career.

One of the most obscure of German Expressionist films

Von Morgens bis Mitternachts (“From Morning to Midnight”) is an early Expressionist film. It came out the same year as Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari. It’s based on a play by one of the major Expressionist dramatists, Georg Kaiser, and directed by one of the major Expressionist stage directors, Karlheinz Martin. The problem is, it never got released in Germany.

Most of the classic Expressionist films are, like Caligari, horror films that motivate their stylization through genre. Von Morgens bis Mitternachts adheres to the subject matter of Expressionist theater, which was vehemently critical of modern society. It centers around a downtrodden bank clerk who suddenly rebels against his apparently happy family life and good job, stealing a huge sum from the bank and trying to run off with a glamorous rich woman who visits the bank. Rejected by her, he wanders away to spend the money in frivolous pursuits.

It’s no wonder that German distribution companies shied away from releasing the film. Its only known theatrical screenings were in Japan, where one nitrate positive print survived. I saw an archival copy years ago. It was an impressive film, more extreme in its stylization than Caligari or even Robert Wiene’s second Expressionist film, Genuine. (All three films were released in 1920.) Unfortunately it had no intertitles, which made it seem all the more radical.

In 1987 censorship records were discovered that allowed the Munich Filmmuseum to reconstruct the intertitles and create the restored version that now has been released on DVD. It’s a significant film, not only as an artistic achievement but as a record of stage  Expressionism of the 1910s. Few plays of the era were filmed, most importantly this one and Jeopold Jessner’s 1923 film Erdgeist, adapted from the play by Frank Wedekind and starring Asta Nielsen and Albert Bassermann. (The play was adapted again by G. W. Pabst as Pandora’s Box, starring Louise Brooks, in 1929; wonderful though that version is, it retains little of the radical Expressionism of the original.)

Expressionism of the 1910s. Few plays of the era were filmed, most importantly this one and Jeopold Jessner’s 1923 film Erdgeist, adapted from the play by Frank Wedekind and starring Asta Nielsen and Albert Bassermann. (The play was adapted again by G. W. Pabst as Pandora’s Box, starring Louise Brooks, in 1929; wonderful though that version is, it retains little of the radical Expressionism of the original.)

Von Morgens bis Mitternachts has some of the most avant-garde set designs of the era. Jagged white sets are smeared across back voids, as in the scene at the top where the protagonist flees down an endlessly winding road after being rebuffed by the woman for whom he impetuously stole money. It records another performance by one of the leading Expressionist actors of the era, Ernst Deutsch, whom I mentioned in my entry on Der Golem. Apart from its jagged sets, the film features a remarkable scene at a bicycle race, with the contestants being filmed in a distorting mirror. It was a technique that the French Impressionists would soon popularize, but Martin may have used it first (see left).

Despite the film’s lack of impact at the time it was made, it belongs squarely within the German Expressionist movement. This release at last allows it to take its place. (The forthcoming issue of the restored Expressionist science-fiction film Algol, also from 1920, will give an even broader picture of the movement.)

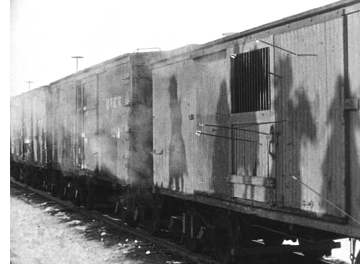

Eureka! Ford is found

The British company Eureka! continues to bring out classic films of all sorts. Its “Masters of Cinema” series has released John Ford’s 1924 western,  The Iron Horse. By this point in his career, Ford has made many western features, only a few of which survive. They were lively low-budget films, but by the early 1920s the western became a prestige genre with the success of James Cruze’s The Covered Wagon in 1923. The Iron Horse was Ford’s move into the high-budget western, and what it lacks in high-spirited energy it makes up for in impressive landscapes and careful dramatic staging. The Indian attack on the train, revealed by shadows (right) is one of the film’s high points.

The Iron Horse. By this point in his career, Ford has made many western features, only a few of which survive. They were lively low-budget films, but by the early 1920s the western became a prestige genre with the success of James Cruze’s The Covered Wagon in 1923. The Iron Horse was Ford’s move into the high-budget western, and what it lacks in high-spirited energy it makes up for in impressive landscapes and careful dramatic staging. The Indian attack on the train, revealed by shadows (right) is one of the film’s high points.