Archive for April 2010

That reminds me …

Enter the Frog Footman in Alice

Kristin here:

One film I can’t work up much enthusiasm about is everywhere, and another I very much want to see doesn’t seem to have a North American distributor. Luckily each reminds me of an older film that isn’t widely enough known. This seems like the perfect chance to point them out.

Recently the latest Screen International, in its new monthly format, arrived, with literally back-to-back reviews of the two films: Tim Burton’s Alice in Wonderland and Sylvain Chomet’s The Illusionist.

Let me say first off that Johnny Depp looks great in eyeliner, as in Pirates of the Caribbean. He looks positively grotesque with pink lips and raccoon eyes. Of course, grotesque could work well for Alice, especially as adapted by Burton. Yet the reviews suggest that the film is actually tamer than one would expect. Screen International’s Brent Simon calls Burton’s film: “A gorgeously mounted but fundamentally humdrum telling of Lewis Carroll’s fantasy novels” (March 2010 issue, p. 61). Variety’s Todd McCarthy makes a similar remark: “But for all its clever design, beguiling creatures and witty actors, the picture feels far more conventional than it should; it’s a Disney film illustrated by Burton, rather than a Burton film that happens to be released by Disney.”

Back in 1951 Disney did a fine version of Alice in Wonderland, one which does capture something of the lunacy of the original. It also benefited from the talent of some of the studios’ best artists, including Mary Blair. Always worth going back to.

But if one wants a truly surrealist, unconventional adaptation, I doubt if anything can top Jan Švankmajer’s feature Něco z Alenky, aka Alice. David and I saw it in a theater when it was released in the U.S. in 1988. It was my first exposure to the great Czech surrealist animator, and we gradually caught up with his earlier films. At the time it had a considerable success on the art-cinema circuit, though I’m not sure how well known it is among younger film fans.

Švankmajer had used both live-action, as in his morbid documentary The Ossuary (1970), and stop-motion animation of objects, as in his brilliant, dark look at human relations, Dimensions of Dialogue (1982). DVD anthologies of his shorts are available. Kino Video’s “The Collected Shorts” volume isn’t as complete as its name may imply. It’s missing several films including The Last Trick, his first but far from least film, and what may be his very best, Jabberwocky (1971), a non-narrative short incorporating Carroll themes. If you’ve got a Region 2 or multi-standard player, opt instead for “Jan Švankmajer: The Complete Short Films,” from the British Film Institute. It has a third disc with extras.

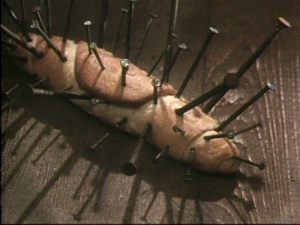

Alice is suffused with a marvelous imagination. Many of the characters are museum specimens. The White Rabbit begins as a stuffed creature in a Victorian glass case, freeing himself by pulling up the nails that keep him rigidly posed. Breadrolls sprout quills made of nails, and unnatural skeletons of creatures straight out of a Bosch painting creep about.

Švankmajer takes advantage of the mingling of two-dimensional figures based on playing cards and three-dimensional figures in ways that few adapters of Alice in Wonderland have managed, as when the White Rabbit passes the Queen of Hearts in a stage setting built of painted flats:

The Mad Hatter in Švankmajer’s film is definitely not Johnny Depp. He’s an antique wooden puppet of the sort that often crops up in the filmmaker’s work. He’s also not as loquacious as the chap in the book. The March Hare, who is definitely mad, steals the scene from him. Buttering a watch’s innards is a pure Švankmajerian gesture.

Alice was Švankmajer’s first feature film. In it he mixed live-action in with the stop-action more than in most of his shorts, presumably in part as a way to save money in making a much longer film. When Alice is full-size, she is played by a real girl, but when she shrinks she becomes a pixilated doll. It works well in this case, but the filmmaker depended more and more on live-action in his later features, like Faust (1994), with animated interludes becoming rarer and rarer. I found these features less entertaining and original and more heavy-handed in their social commentary. (The shorts contained vicious satire, but it was often rendered in bizarre, striking ways that made it palatable.) After thoroughly disliking Conspirators of Pleasure (1996), I gave up on his new films and stuck with the old ones. He’s making one now, called Surviving Life, which he apparently has said will be his last.

A final word on Alice. As should be obvious, this isn’t your charming adaptation for children, at least small ones. Alice points that out during the credits, “Now you will see a film made for children. Perhaps.” Most kids these days seem to be more hard-boiled than in my youth, but seeing this film at age 10 would have left me with nightmares. The White Rabbit, scarier than any fuzzy little bunny I’ve ever seen (including the one in Monty Python and the Holy Grail), runs around with scissors, quite willing to obey the Queen of Hearts’s order, “Off with her head!”; the little skeleton creatures crawl over Alice; and creepy glass eyes give staring life to inanimate objects like the Frog Footman or the sock that turns into the Caterpillar:

They tend to stare right out at us, too.

Tati on Parade

Most readers of this blog will be familiar with the great Jacques Tati. But it was news to me that he had left an unproduced screenplay, finished in the 1950s and now adapted by French animator Sylvain Chomet. Those who saw Chomet’s first feature, the 2D animated film The Triplets of Belleville (2003), probably noticed the occasional Tati homage lurking in the backgrounds and on the walls. Now Chomet’s admiration for Tati has emerged front and center in his second animated feature. The Illusionist‘s protagonist is modeled directly on Tati; he’s a old-fashioned magician eking out a living in the fading world of music-halls. (The Russian trailer has been posted here; apparently that’s the only footage on the internet so far.)

The Illusionist premiered at the Berlin Film Festival this year and met with a warm reception from critics. Writing in Screen International, Lisa Nesselson calls it “a delightfully bittersweet valentine to the music-hall tradition” and says that its animation “simply could not be better” (March, 2010 issue, p. 62). Leslie Felperin’s Variety reviews dubs it “a very happy marriage of Tati’s and Chomet’s distinctive artistic sensibilities.”

While we are waiting for an American distributor to pick up the film (ahem!), let me recommend Tati’s least-known feature. After his financial difficulties in the wake of Play Time‘s high budget and tepid box-office performance, the director set out to make Traffic, his last film featuring his M. Hulot character. Funding on this film collapsed midway through shooting, but Swedish TV stepped in and bailed the production out. Traffic came out in 1971, and in exchange for the assistance Tati made the 85-minute telefilm Parade (1974).

It has been available on French DVD (now out of print), but now the British Film Institute has released its own edition. The transfer isn’t the greatest, though it seems to be the same or similar to the French version. It smooths over the peculiarities of the original film. David and I saw it in 35mm in Brussels (where we also saw The Triplets of Belleville). It was obvious that while most of the film had been shot on somewhat fuzzy video in front of a live audience, some acts had been staged in a studio on crystal-clear 35mm. It was an oddly mixed format for an odd film. The BFI version also features optional English subtitles. Given the paucity of audible speech, they don’t seem vital.

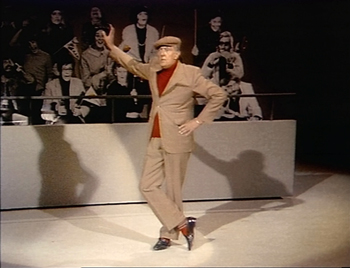

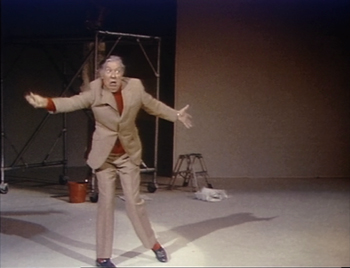

After the audience files in and takes their seats and an opening parade introduces the main acts, Tati steps forward as emcee and informs the spectators that they will be as much a part of the show as the performers onstage. Sure enough, the audience has been staged by Tati, accoutered in outrageous, colorful outfits and instructed to turn their heads back and forth rhythmically during his tennis routine or to bounce balloons around. Occasionally “ordinary” people from the stands step forward to challenge the acts onstage, trying and sometimes succeeding in out-doing them in magic or musical performances. The black-and-white life-size cutout people that had been used as extras in the backgrounds of scenes in Play Time return here as prominent members of the audience and even the stage acts. In the scene of Tati’s mime of a goalie (see below), the cutouts provide an unmoving backdrop to the action.

After the audience files in and takes their seats and an opening parade introduces the main acts, Tati steps forward as emcee and informs the spectators that they will be as much a part of the show as the performers onstage. Sure enough, the audience has been staged by Tati, accoutered in outrageous, colorful outfits and instructed to turn their heads back and forth rhythmically during his tennis routine or to bounce balloons around. Occasionally “ordinary” people from the stands step forward to challenge the acts onstage, trying and sometimes succeeding in out-doing them in magic or musical performances. The black-and-white life-size cutout people that had been used as extras in the backgrounds of scenes in Play Time return here as prominent members of the audience and even the stage acts. In the scene of Tati’s mime of a goalie (see below), the cutouts provide an unmoving backdrop to the action.

The BFI DVD includes a brief but informative booklet with essays by Philip Kemp and Jonathan Rosenbaum. As Kemp  points out, the acts out of which Tati built his film are, apart from himself, not much to boast about: “His colleagues’ juggling, acrobatics, and, literally, horseplay (much use is made of an upright piano that doubles as a vaulting-horse) are diverting but nothing special.” Yet that, I suspect, is part of the underlying strategy. The film is quite Tatiesque, despite its lack of M. Hulot or a real plot. The juxtaposition of the three separate spaces of the audience, the stage, and the carpenters’ shop directly abutting the performance space, allows the creation of the sort of visual jokes that Tati loves. It also permits a flow between roles, as when the “carpenters” emerge briefly to juggle with their brushes or to play their tools like xylophones before returning to work. All these performers are quite good, but really great acts would distract from the best act of all: Tati’s overflowing visual imagination.

points out, the acts out of which Tati built his film are, apart from himself, not much to boast about: “His colleagues’ juggling, acrobatics, and, literally, horseplay (much use is made of an upright piano that doubles as a vaulting-horse) are diverting but nothing special.” Yet that, I suspect, is part of the underlying strategy. The film is quite Tatiesque, despite its lack of M. Hulot or a real plot. The juxtaposition of the three separate spaces of the audience, the stage, and the carpenters’ shop directly abutting the performance space, allows the creation of the sort of visual jokes that Tati loves. It also permits a flow between roles, as when the “carpenters” emerge briefly to juggle with their brushes or to play their tools like xylophones before returning to work. All these performers are quite good, but really great acts would distract from the best act of all: Tati’s overflowing visual imagination.

Ultimately, though, the main boon of Parade was to preserve for posterity Tati’s famous series of sport-based pantomimes that he had developed in the 1930s, when he was a successful stage performer. He started off on the same music-hall stage that he celebrates in Parade and now, posthumously, in The Illusionist. Some of these mimes, such as the man-and-horse trick rider, the over-confident goalie, the over-the-hill boxer, or the disappointed fisherman (bottom) may have remained unchanged across Tati’s career. (After he became famous as a filmmaker and actor, he often had the chance to perform these brief skits on TV variety and talk shows.)

Horse-man

Goalie

Boxer between rounds

Tennis in slow motion

There’s one magic moment in these mimes, however, that Tati presumably updated. During the tennis match, he lapses briefly into slow motion. Not a slow motion achieved in the camera, which keeps running at normal speed. No, he mimes a player as seen in slow motion, quite convincingly and yet moving in ways that one wouldn’t consider possible for the human body. It’s hard to describe, but believe me, it’s amazing to watch.

Tati’s performances as the postman in Jour de fête or as Hulot in the four films featuring that character are usually not flashy. They’re designed to merge into the story and make the hero one of many amusing characters in an ensemble. But in Parade, with the pantomimes performed outside a narrative context and primarily against dark or blank white backgrounds, we can savor the man’s dazzling skill. His utter control of every gesture echoes his directorial mastery of every stylistic component of his films. In Parade, the moments when he tries to subdue a flapping fish before it escapes or when his head snaps back in reaction to an imaginary opponents’ blows are mindboggling in their precision. He was a great actor before he was a great filmmaker, and fortunately that early skill lingered long enough to be recorded.

Gone fishing

The Omnivoyeur’s dilemma

Otouto.

DB here:

Any major film festival is really many festivals. You meet someone who tells you about all the films they’ve been seeing, and the overlap with your dance card is virtually nil. You’ve both been in the same town, and probably hit the same venues, but you’ve been to different festivals.

Then there are certain syndromes. You convince yourself you need to see 3-5 films a day. Otherwise, what’s the point of traveling all this way? Soon you realize, horribly, that after a couple of days of this regimen, you can’t recall what you’ve seen. Some early afternoon, Festival Amnesia will set in, and you can’t remember what you saw that morning. Was it that ambitious but ultimately unsatisfying little romance from the Bosporus? Or the Chinese movie about moping teenagers trying to leave their dingy village? What were the names of those movies, anyhow?

My own symptoms are getting acute. Twice in recent years, I have found myself in front of a film suddenly realizing that I had seen it at another festival. I had forgotten the title. At least I caught my mistake with the first shots, but I expect that in time I will obliviously sit through the whole movie twice—probably liking it on the first pass and declaring it disappointing on the second.

Then there’s Viewer’s Remorse. Watching 3-5 titles a day, you inevitably encounter some stinkers. You take this philosophically until you meet someone else, who rhapsodizes about the string of masterpieces they’ve seen. Suddenly you realize that you have backed losers. Your friend has had a transformative festival experience, and you might as well have been flossing. Worse, your carefully picked mediocrities swell in your mind, blotting out the good films you managed to catch by dumb luck. Panicked, you thumb through the schedule to see if the great things you’ve missed are playing a second time.

They aren’t.

So film festivals aren’t by any means the sweet deal they may at first seem. Even putting aside queueing, officious door staff, racing between venues, and projection problems, there are plenty of features to make people like me more neurotic than we already are.

But I can’t complain about my latest visit to Hong Kong. True, breathing problems put me out of commission some days and eventually forced me to return home early. My biggest regrets were missing the Zanussi films and the two Angelopolous films, The Weeping Meadow and The Dust of Time. (Watch: Somebody will tell me they are all masterpieces.) Still, I managed to see a fair amount in two mini-festivals I carved out of Filmart and the festival proper.

Turning Japanese, yet again

Golden Slumber.

Parade, from director Isao Yukisada, is an ensemble picture about Tokyo twentysomethings sharing a flat. Their love affairs and marathon viewings of soap operas are disrupted when Satoru, a male prostitute, crashes there one night and winds up hanging around with them. With his blank passivity and ambisexual good looks he arouses their curiosity and, as usual in such movies, winds up changing everyone’s lives. The film was pretty good at portraying the way the kids keep life intriguing by conjuring up mysteries about their neighbors. (Is the man next door running a brothel?) The plot ran out of steam, I thought, but I enjoyed seeing a movie in that sober style that apparently only the Japanese can now pull off: only about 400 shots in nearly two hours, with an unassertive fixed camera that gave the characters room to breathe.

Also about a young cohort, but more action-driven, was Golden Slumber, by Nakamura Yoshihiro. He directed Fish Story (2008), a favorite of mine from last year’s festival. This one is about a hapless young man pulled into a plot to assassinate the prime minister. Threaded with glimpses of his college days, when he and his pals worked in a fireworks shop and became connoisseurs of fast food, the plot follows his efforts to avoid arrest and find how he was framed. Like a lot of contemporary Asian films, Golden Slumber sounds a note of nostalgia not only for long-lost innocence but also for kids’ self-consciously retro tastes in popular culture—in this case, the Beatles song “Golden Slumbers” (“Once there was a way to get back home . . . .”). Less zany than Fish Story, whose story pivoted around how an obscure album prepared for the end of the world, this seemed to me finally quite agreeable, thanks to its likably awkward hero and its lovelorn ending.

Longtime readers of this blog won’t be surprised that one favorite of my personal Japanese mini-fest was Yamada Yoji’s tear-jerker Otouto (aka Ototo, “Younger Brother”), a remake of a 1960 Ichikawa film. A widow who ekes out a living as a pharmacist is about to marry off her beautiful daughter. But during the wedding dinner her ne’er-do-well brother pops up and turns the ceremony into a catastrophe. Japanese movies are very good at evoking social embarrassment, and the disruption caused by Tetsuro makes you wriggle in your seat. He could have been simply a lovable loser, but he’s not that likable, let alone lovable, and his waywardness brings misfortunes on his sister’s family. In this movie about how you must love your relations no matter what, Yamada shows the classic resignation to family ties that has characterized the films from the Shochiku studio since the 1920s.

As usual with Yamada, the direction is crystalline in a way you hardly ever see now: calm framings, unhurried pacing, longish takes (about 12 seconds on average), and lighting and composition that etch every object in relief. When Ginko the mother peels an apple, the skin curls off in a long ribbon, and it’s as fascinating as a car chase in any other movie. In a film in which the camera seldom moves, a handheld shot regains some of its original power. Maybe I’m what Groucho called a sentimental old fluff, but like Kabei–Our Mother, Otouto shows that some cinematic traditions are still worth something.

For the real Shochiku flavor, experts will tell you, you need to return to the 1930s, and the festival did so with its small retrospective of Shimazu Yasujiro. A prolific director of comedies and dramas (he made over a hundred silent films), Shimazu built a reputation in the 1920s with family dramas like Father (1923). Most of his films are lost, and he died in 1945, so he didn’t benefit from the postwar revival of the industry and its growing renown in the West. His most famous work is probably the ingratiating Our Neighbor Mis Yae (1934), which features in the retrospective.

The remaining Shimazu films don’t seem to me to reveal the stylistic consistency we find in Ozu or Mizoguchi or Shimizu. There are flamboyant pictorial touches in First Steps Ashore (1932), a drama of sailors and prostitutes with stark lighting and cluttered sets influenced by The Docks of New York.

A fight scene is rendered in a long-lens shot that looks very modern, though the technique had already been seen in Japanese swordplay films.

Perhaps most original are the variants Shimazu works on a picturesque divider in a waterfront bar, which becomes a fascinating grid that sorts out faces.

Having been trained by this cheese-grater divider, we are given the tougher task of spotting the seaman peering from the distance at our stoker hero and the taxi dancer he rescues. (Not so easy to see in my still: He’s watching from the square and circle aligned horizontally behind the hero’s lips and chin.)

This “game of vision,” where we must strain to see action that’s blocked by bits of setting or furnishing, is characteristic of Japanese film then and since.

Okoto and Sasuke (1935) and Lights of Asakusa (1937), the two Shimazus I caught during my stay, aren’t as visually tricky as First Steps Ashore, but they display Shimazu’s characteristic interest in marginal characters (a blind woman in Okoto, stage performers in Asakusa). Both films close with a self-sacrificing retreat from the world. Later films, including the wonderful Brother and His Younger Sister (1939), would give this retreat a positive ideological spin. Disgusted by office politics, a young man takes his sister and mother to Manchuria to start anew, and the finale shows a clump of earth clinging to the plane wheels, as if a bit of Japan’s very soil would sanctify the empire’s new outpost.

Fei Mu, Film Poet

Nightmares in Spring Chamber.

A second mini-festival during my Hong Kong stay centered on Chinese film history. I’ve mentioned the Patrick Lung Kong titles in an earlier entry. The other prime figure was Fei Mu, celebrated as one of China’s best filmmakers. His Spring in a Small Town (1948) is often considered the greatest of all Chinese films, and it’s not an unreasonable judgment.

Unfortunately, only about half of Fei’s output survives. The earliest film we have is Song of China (aka Filial Piety, 1935), a paean to Confucian virtues. Parents permit their son to move to the city, but the son falls prey to self-indulgence and a temperamental wife. Even when he holds a banquet to honor his parents it is merely an excuse for what the father calls “revelry and gambling.” Soon the daughter is being seduced by a city slicker and told that “parental consent is a timeworn tradition.” This lesson in traditional morality is filmed quite fluently, with telling use of tracking shots, especially during the banquet, and sudden bursts of angular montage.

On Stage and Backstage (1937), from a Fei Mu script, is a 37-minute comedy. A troublesome diva refuses to come to a performance unless she’s paid, but the manager can’t afford it. So a street performer is brought in to substitute for the star in a performance of Farewell My Concubine. While the production is shot frontally and with little depth, director Zhou Yihua contrasts that area of action with the backstage milieu by means of layered compositions and lateral tracking shots through tangles of ropes and props. I enjoyed this charming film when I saw it during my first trip to Hong Kong, and its appeal held up well for me.

I came home too soon to catch Bloodshed on Wolf Mountain (1936), usually considered a strong work, and the little-seen Children of the World (1940). Other films in the series included The Show Must Go on (1952) from a Fei script and Romance in the Boudoir (1960), from Fei’s brother Louis; I already discussed the latter here. There were also two Chinese Opera films. A Wedding in the Dream (1948), China’s first color film, stars the legendary Mei Lanfang, the Peking Opera performer best known in the west who became friends with Chaplin and Eisenstein.

This image from Wedding in the Dream is a posed production still; the film itself, a straightforward record of Mei’s performance, survives in dreadfully worn condition. I found Murder in the Oratory (1937) more intriguing. A man is urged by his mother to murder his wife, the daughter of the man who killed his father. From the start, when an opera stage dissolves into a fully three-dimensional space, you realize that this will be an experiment in creating something halfway between canned theatre and a “filmic” treatment. So we get all the trappings of an opera performance, including stylized movement and singing, but with the camera weaving among the characters and furnishings, finding unusual angles, and even assuming characters’ optical viewpoints.

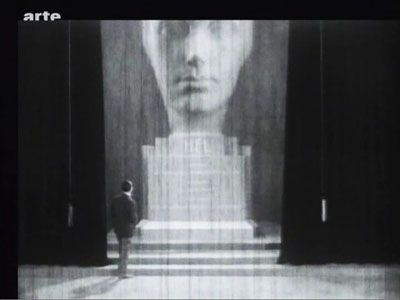

Far different is another title I enjoyed on my first visit to Hong Kong in 1995. Nightmares in Spring Chamber (1937) is an episode in the portmanteau film Lianhua Symphony. This 13-minute allegory of Japan’s imperial ambitions shows a maniacal frock-coated Japanese pursuing innocent Chinese girls through a vast bare villa. He cackles over a spinning globe and captures one girl, but she’s rescued by the other, a surrogate for the Chinese soldier we glimpse occasionally. Full of canted angles, hallucinatory visions, under lighting, looming shadows, and other trappings of German Expressionism, and accompanied by snatches of Debussy and the Danse macabre, it’s a far cry from the other items in the series, and it suggests a director of considerable versatility.

Last year the Festival premiered the restoration of the rerelease of Fei’s 1940 Confucius, which I wrote about then. This year a second restoration inserted titles to cover the gaps and put some scrappy scenes into their proper order. In addition, a very informative book, Fei Mu’s Confucius, accompanied the screenings. The essays explicate the film from several angles, including its relation to Confucian doctrine, to classic poetry and painting, and to other Fei Mu works.

Thanks to retrospectives like this one, we can see how much Fei’s official masterwork owes to his earlier efforts. There are touches of lighting and staging in these films that are more subtly developed in Spring in a Small Town, and the stately pacing of Confucius is here put to more mundane subject matter. Still, nothing I saw matches the quiet erotic boldness of this milestone of world cinema, which anticipates so much of what we find in Antonioni and other postwar European filmmakers.

So much to see, and even less time than I’d planned: Film festivals somehow manage to leave you unsatisfied and yet feeling full. A nice dilemma to have.

Spring in a Small Town.

METROPOLIS unbound

Fritz Lang has created a lot of pretty pictures and has discovered the astonishing talent of Brigitte Helm. I cannot blame him for not being able to cut the quantity of ideas in individual scenes mercilessly enough (the water catastrophe, the duel), but instead repeatedly trying out new lighting and angles. This time the film’s qualities lie precisely in these efforts: and if the viewer knows how to make the best of something, he will derive pleasure from these images.

Rudolf Arnheim, review of Metropolis, 1927.

Along with La Roue and The Battleship Potemkin, Metropolis (1927) is one of the great sacred monsters of the cinema. Many versions circulate, and restorations never seem to stop. A beautifully restored, though incomplete, version was premiered in Berlin in 2001. This is the basis of the most authoritative DVD releases. By now, however, everybody has heard about the 2008 discovery of a significantly longer version in Argentina, a 16mm preservation copy drawn from a scratch-infested 35 nitrate original.

Since 2008 a team at the Friedrich-Wilhelm-Murnau-Stiftung has been at work adding material from the Argentine version to the earlier one. Kristin and I have written earlier entries (here and here) tracing the progress of the restoration, and the team have produced a detailed website explaining their work. The result made its world premiere at the Berlin Film Festival earlier this year, and an exhaustive exhibition about the film has been running at the Deutsche Kinematek in Berlin.

Now I’ve seen it, at a screening during the Hong Kong International Film Festival. Frank Strobel, a member of the restoration team, conducted the Hong Kong Sinfonietta, and another collaborator, Martin Koerber, curator at the Deutsche Kinematek, was present to discuss the restoration process. A handsome booklet, cosponsored by the Goethe-Institut of Hong Kong, provided a lot of background. The film was projected digitally, but at very high resolution and looking quite crisp. I had a front-row center seat. I had a swell time.

Metropolis has never been my favorite Lang of the period, but this version makes the strongest possible case for the film. It’s hard to dislike its shameless, preposterous ambitions, its stew of biblical and modern ingredients, its bold architectural vistas, and its trancelike characterizations. Also, people running crazily about in gargantuan spaces can usually hold your interest.

I just met a girl named Maria

All [the American editors] were trying to do was to bring out the real thought that was manifestly back of the production and which the Germans had simply “muffed.” I am willing to wager that “Metropolis” as it is seen at the Rialto now is nearer Fritz Lang’s idea than the version he himself released in Germany. . . . There was originally a very beautiful statue of a woman’s head, and on the base was her name–and that name was “Hel.” Now the German word for “hell” is “hoelle” so they were quite innocent of the fact that this name would create a guffaw in an English speaking audience. So it was necessary to cut this beautiful bit out of the picture . . . .

Randolph Bartlett, The New York Times, 13 March 1927

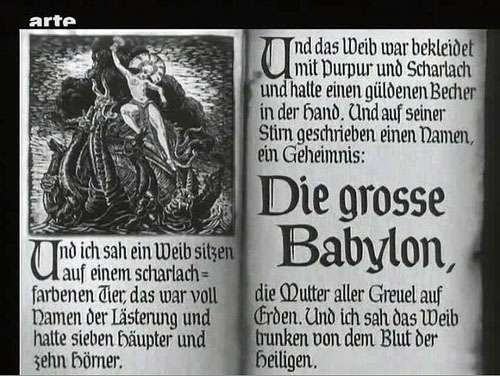

The new version gives the film a better narrative balance. Somewhat surprisingly, the plot hinges on one of the oldest and simplest narrative devices: mistaken identities. The overlord Fredersen engages the crazed scientist Rotwang to create a mechanical Maria who will lead the workers astray. Rotwang takes the occasion to avenge himself on Fredersen by having his robot urge the workers to destroy the machines. Two Marias, then–actually more, if you count the robot Maria’s incarnation as the Whore of Babylon in the Yoshiwara Club.

Thanks to the Argentine footage, we now know that another major character doubling involves Freder. At the start of the version we all know, Freder is visited by Maria and a flock of children. Upon seeing her radiant charity, he becomes suddenly convinced that he must join the oppressed workers, his “brothers and sisters.” Helping them has become his destiny. He gains an ally in Josaphat, an employee whom his father has brusquely fired. Descending to the cavernous machine halls, Freder switches identities with Georgy, a worker who returns aboveground to live Freder’s life. Freder wants him to go to Josaphat’s apartment, where they will meet. But the Thin Man, a long, leering hireling of Freder’s father, is charged with trailing Freder.

Stretches of the Thin Man subplot are missing from the previous version, but now we can see that Georgy/ Freder is a sort of early counterweight to the Maria/ Maria parallels. As in the latter case, the switch leads to misunderstanding, with the Thin Man following Georgy to the club and eventually to Josaphat. The Georgy substitution also allows Harbou and Lang to introduce the Yoshiwara Club early, but teasingly, in a rapidly dissolving montage. Only later will we get a good look at the delicious degeneracy inside.

As Martin Koerber indicated in several remarks, the older, most common version of Metropolis turns it into a science-fiction film, since it puts the robot Maria at the center of the plot. Just as important, though, is Freder’s plan for overturning class oppression, something fleshed out in the Georgy/ Josaphat material. Other new footage puts the relationship between Fredersen and Rotwang in a new light. We now see that Rotwang was in love with Fredersen’s wife Hel, and he has constructed not only a huge bust of her but also a “mechanical man,” outfitted with a distinctly female anatomy, as a sort of Hel substitute.

Fredersen diverts Rotwang’s plan to the purpose of mimicking Maria. So we get another doubling: Freder’s mother Hel becomes the firmware for the robot Maria through the machinations of two father figures. (Freder will kill one and redeem the other.) In all, the new footage yields a play of eerie Freudian substitutions.

The 2010 restoration also establishes the film as consisting of three large-scale movements. The first section, “Prelude” (Auftakt), runs a bit more than an hour. It shows Freder joining the workers and his father planning to have the Thin Man follow him. This part also introduces Rotwang, establishes Fredersen’s order to make a robot Maria, and ends with Rotwang’s capture of Maria. A second part, called “Intermezzo” and lasting about thirty minutes, is devoted to intertwining the Freder/ Josaphat plot with the creation of the robot Maria. The section more or less climaxes with a demo of the new Maria, dancing sexily at the Yoshiwara.

In “Furioso,” everything builds to a climax across a remarkable fifty minutes. The cloned Maria leads the workers to destroy the machines, fulfilling Rotwang’s plan to avenge himself on Fredersen, while the real Maria escapes from Rotwang’s compound during a fight between Rotwang and Fredersen. (We’re still lacking some of this footage.) At the same time, Freder and Josaphat converge on the underground city. The workers’ smashing of the machines triggers a flood from which the children must be saved. At the finale, during a hand-to-hand struggle with Freder, Rotwang falls to his death. There follows the famous epilogue in which Freder, “the Mediator,” must bring together hands (the foreman Grot) and head (the capitalist Fredersen).

Fluidity and freedom

This delirious fable is rendered with unrelenting zest. Lang has now perfected his breathless version of silent-film narration. He relies on simple, immediately graspable compositions, rapid crosscutting among different plotlines, and a dynamic approach to analytical editing.

In the late 1920s, many American films became more heavily dependent on intertitles; it’s as if directors were anticipating talkies. But of Metropolis’s over 1800 shots, I counted only 26 expository titles and 156 dialogue titles—in a film running nearly 2 ½ hours. Lang plunges us into each scene with no fuss, and once we’re there, a smooth continuity carries us from shot to shot. Confronting the seven deadly sins in the cathedral, Freder turns away, twisting Georgy’s cap in his hands as he exits the frame.

Cut to the main area of the cathedral, and Freder is still twisting the cap as he enters the frame. (Like other shots from the Argentine version, this is slightly reduced because of the 16mm source.)

He lifts the cap, and we get his point of view on Georgy’s name and number.

Cut to the Yoshiwara nightclub closing, as Georgy steps groggily into the street.

Here the new footage lets us see that Lang is exploiting the sort of verbal and imagistic hooks he had developed in earlier films: from Georgy’s cap to Georgy himself, with no need of an intertitle to take us to the new scene.

Lang’s freedom of camera position is typical of late silent cinema, but he deploys his angles with characteristic precision. As usual in Europe, Hollywood-style continuity isn’t completely adhered to—there are some crossings of the 180-degree line—but Lang is careful to keep us oriented to the action through eyelines. This allows great flexibility in camera placement.

Fredersen is dictating to his secretaries while Josaphat is monitoring prices. A vast establishing shot shows all of them.

Fredersen’s pacing around his office allows Lang to introduce a new area around the window and the desk.

Now pacing in the center of the office, Fredersen pauses in his dictation and Freder bursts in behind him.

But Fredersen, who’s already holding up one hand as he speaks, simply twists his wrist, and this silences his son.

The shot approximates Freder’s point of view, but Lang gets a bonus from it. The sharp change of angle makes the imperious hand (and not, say, Fredersen’s expression) the compositional focus of the shot. In fact, this sort of hovering hand will become part of the characterization of Fredersen, and Lang will stress it through, once more, energetic changes of angle.

And still later, the framing will spotlight Freder’s pointing finger by pushing it to one zone on the far right of the shot.

Lang’s concise handling of such small actions forms a delicate counterbalance to the mass movements elsewhere in the film. Perhaps for him, both gestures and crowd scenes are merely two ways of creating a geometry that can activate every area of the screen.

The carefully controlled freedom of spatial construction is facilitated by one of Lang’s favorite tactics: shooting from directly on the axis of character interaction. (No, Wes Anderson didn’t invent this.) Lang in effect sets the camera between the two characters so that they stare out at us, as if mesmerized. The technique is most memorable in the scene in which Freder is confronted by Maria and the children.

Again, though, the Argentine material brings more instances to our attention.

Putting the camera on the axis allows Lang leeway in changing his angles. From a shot on the center line, you can cut to pretty much any other area of space.

Lang’s crisp visual narration comes to a climax in the well-named Furioso section. As the action ramps up, the characters rush from spot to spot, hurling themselves into the frame and then abruptly halting to hold the composition.

The extreme case is the robot Maria, whose head and limbs jerk puppetlike from one position to another.

In all, Lang’s precise, almost diagrammatic visual style rushes us through the film’s wild plot and dazzling architecture. An emblem of precision in the service of slightly demented material might be that memorable close-up of the robot Maria: One eye staring out normally, the other half-closed, and the mouth half-twisted in a leer, as if the circuitry in the skull was failing.

A little encyclopedia

Martin Kroeber, Togichi Akira, Winnie Fu, Sam Ho, and Wong Ain-ling discuss preservation and restoration at the Hong Kong Film Archive.

In a Q & A after the screening, Martin Koerber and Frank Strobel shared information about the version. They and their colleague Anke Wilkening could publish a whole book about the restoration, but here are some highlights, drawn as well from Martin’s comments at a lengthy seminar at the Hong Kong Film Archive.

*Sources for information about the premiere version include a copy of the script (helpfully marked with reel ends and calculations about running time), censorship cards recording the credits and intertitles reel by reel, Gottfried Huppertz’s musical score, and thousands of production stills.

*Using these materials, earlier researchers were able to create a sort of mosaic of the version that premiered in Berlin in January 1927. The resulting study film embedded long swathes of blank footage as place-holders. The fact that the Argentine shots fitted in neatly proved the validity of that edition. This study film may be ordered on DVD at nominal cost by educational and research institutions.

*What’s still missing? Some shots in the Argentine version may have been censored; we’re missing a bit in which Georgy, at liberty in a cab, sees a woman baring her body. Also lacking is nearly all the fight between Rotwang and Fredersen, which enables Maria’s escape. In addition, the Argentine print lacks a scene showing a monk preaching in the cathedral, which yields some apocalyptic images.

*If the film plays fast for contemporary tastes, don’t blame the restorers. This version runs at 24 frames per second. Actually, for the 1927 premiere the film was run even faster. The score includes passages accompanying missing footage as well as over a thousand synch-points for specific onscreen action. On the basis of this evidence, it seems that the film was designed to run at about 28 frames per second. This reminds us that silent-film running speeds were far from standardized, and they sometimes exceeded the 24 fps that would be established for sound film. (For more on this matter, go here and scroll down a bit.) In addition, Frank mentioned that in theatres with orchestras, the conductor could regulate the speed of the film with a dial set into the podium.

*Why insert the cropped 16mm footage in such obvious fashion? Couldn’t the framelines be adjusted to match the surrounding 35mm material? Yes, but this slight blowup of the footage would falsify the shot scale of the original footage and not match comparable shots in the 35mm footage. Moreover, Martin pointed out that because not all the scratches and fuzziness of the 16mm material could be purged, it’s better to let these stand stand out somewhat as evidence of the vagaries of film history–like leaving some damage visible in historic buildings.

*Why is the restoration in black and white, since most silent film restorations are in color? Lang was opposed to tinting and toning, so Metropolis premiered in black and white. This caused a debate among critics, some of whom considered it a promising departure from contemporary practices of coloring scenes. The tinted versions that one can occasionally see are likely export versions colored at the request of distributors in particular markets.

*Although future screenings of the 2010 version are to be accompanied by other ensembles devising their own music, there’s a powerful case for retaining Huppertz’s original score. It reflects the filmmakers’ intentions, and its Wagnerian romanticism and modern rhythms are enjoyable simply as music. Just as important, Huppertz designed his score around leitmotifs that, as in opera, can call to mind characters who aren’t onscreen at the moment.

*Metropolis, Martin argued, is too often considered simply a late Expressionist film or an early science-fiction effort. Now we can see that it’s much more: “a compendium of everything in the air in 1927 Germany.” It brings together political ideas, debates about class society and urban life, current trends in the fine arts, acting styles, and cinematic experiments. It owes a great deal to the “monumental” films of the late 1910s, such as Joe May’s Herrin der Welt (1919), but it’s also a synthesis of what filmmaking had become since then. “It’s a little encyclopedia of 1927 cinema. . . . There’s something in it for everybody.”

To see the restoration with the stirring score, vigorously conducted by Frank, was a high point of my Hong Kong trip and indeed of my filmgoing year.

This version of Metropolis was simulcast, if that’s the right word, on 12 February by Arte during the premiere at the Berlin International Film Festival. My frames are taken from that broadcast version; hence the bug. The restoration will be screened on Turner Classic Movies in the fall, and then released on DVD in the US by Kino International.

The epigraph quotation from Arnheim comes from Film Essays and Criticism, trans. Brenda Benthien (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1997), 119. The article about the US cut of the film, which became widely seen around the world, is Randolph Bartlett, “German Film Revision Upheld as Needed Here,” New York Times (13 March 1927), X3.

Thanks to Martin Koerber for an abundance of information. For further reading, he recommends Erich Kettelhut’s memoirs on designing and filming the project, Der Schatten des Architekten (Munich: Belleville, 2009), ed. Werner Sudendorf, with many documents from sketches and photos; and the Deutschen Kinemathek exhibition catalogue, Fritz Langs Metropolis, ed. Franziska Latell and Werner Sudendorf (Munich: Belleville, 2010). You can get a sense of the tangled history of the versions of the film from Martin’s article in the latter volume, which includes a detailed account of the digital restoration. An earlier version of his piece, keyed to the 2001 version, is available as “Notes on the Proliferation of Metropolis,” in Preserve Then Show (Copenhagen: Danish Film Institute, 2002), 128-137. The Metropolis exhibition runs through 25 April.

A special thanks to Lee Tsiantis, Langian extraordinaire.