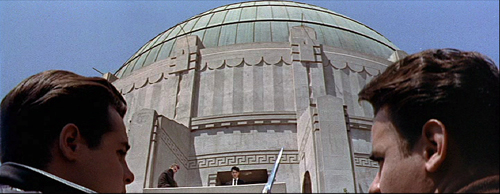

Rebel without a Cause (1955).

KT here:

It’s time for our annual scan of the past year’s entries, pointing particularly to ones that might be useful to teachers and students using Film Art: An Introduction. For occasional readers of the blog, this post might be useful in catching up on items you might have missed.

This year we’ve added four video essays and lectures to our site. These have entailed a lot of effort, but David has enjoyed making them as free complements to the briefer, walled-garden video essays [2] accompanying our latest edition of Film Art.

We’re also delighted to include some entries based around encounters we have had with filmmakers (some of whom we met as a result of our blog) and two contributions from guest experts. Looking back, we are as usual surprised at how much material has accumulated in one year. The summer’s new movies may on the whole have disappointed, but obviously there are a lot of other interesting topics to explore outside the multiplex.

For earlier blog-roundups, see 2007 [3], 2008 [4], 2009 [5], 2010 [6], 2011 [7], and 2012 [8].

I’ll go through Film Art chapter by chapter, suggesting relevant entries for each, and end with a couple of entries on new DVDs that teachers might want to add to their personal or departmental libraries.

Chapter 1 Film Art and Filmmaking

Last year, David’s “Pandora’s Digital Box” series [9] dealt with the transition from film-based to digital-based production and distribution. (That series was revised and expanded into a book [10].) The original series is updated in “Pandora’s Digital Box: End times.” [11]

This year, David looked back on some historical formats. In “The wayward charms of Cinerama,” [12] he reviewed Flicker Alley’s DVD release of This is Cinerama and took the occasion to analyze the peculiar perspective relations created by the triple-camera system. How the West Was Won and The Wonderful World of the Brothers Grimm receive some stylistic scrutiny.

Super 16mm is still a significant gauge for independent filmmaking, but regular 16mm as has largely been replaced by DVD and Blu-ray for classroom and film-buff viewing. David waxes nostalgic concerning the charms of 16mm and its importance in our own film-watching careers in “Sweet 16” [13] and “16, still super.” [14] For those too young to have seen 16mm on a screen, these recollections might make it a bit more vivid.

Nothing conveys the tangible work of film production like a visit to a working set. Our colleague James Udden, expert on Taiwanese cinema, had an opportunity to watch a major contemporary director in action and reports for us in “Master shots: On the set of Hou Hsiaeo-hsien’s THE ASSASSIN.” [15]

Publicity is a big part of the distribution of a modern blockbuster. In “Jack and the Bean-counters,” [16]I examine the missteps in the campaign for Jack the Giant-Slayer and talk about how the studios avoid cooperating with fans eager to provide valuable free online publicity for their favorite films.

Chapter 3 Narrative Form

Films often use repetition in an obvious way to help us easily follow a story. But what about filmmakers who introduce more subtle similarities that challenge our memories? We examine two such films made in South Korea, In Another Country and Romance Joe, in “Memories are unmade by this.” [17]

Repetition is also central to Mildred Pierce, where a murder that happens at the beginning of the film is seen again, with different shots and timings, near the end. We look at how the film fools us without our noticing it. The sequences are here:

“Twice-told tales: MILDRED PIERCE” [18]analyzes the different functions and effects of the two sequences.

Art films and classics are not the only films with intriguing storytelling. “Clocked doing 50 in the Dead Zone” [19] is an analysis of David Koepp’s Premium Rush as a short film that packs a lot of action and clever narrative tactics into its running time. That entry led to a meeting with Koepp and a follow-up entry on his approach as screenwriter and director. See the Chapter 8 section.

Chapter 5 The Shot: Cinematography

Seeing some recent Asian films at the 2012 Vancouver International Film Festival led to “Stretching the shot,” [20] some thoughts on functions for the long take.

A lot of the films we see in theaters today are made in anamorphic widescreen processes, and by now letterboxing for home-video is familiar to all. David has often lectured on the history and aesthetics of the first successful anamorphic process, CinemaScope. Now that PowerPoint lecture is available on his Vimeo site. See “Scoping things out: A new video lecture” [21] for an introduction and link. (It’s about 53 minutes long, so perhaps something to assign your students to watch on their own.)

Chapter 6 The Relation of Shot to shot: Editing

“News! A video essay on constructive editing” [22] introduces the additionof an analysis of editing in Robert Bresson’s Pickpocket to Vimeo. It’s about 12 minutes long, suitable for classroom use or assignment for students to watch outside of class. Our thanks to our friends at the Criterion Collection [23] for their permission to use the excerpts from Pickpocket.

How much can a single cut reveal about the power of editing? “Sometimes two shots …” [24] takes a close look at a brief passage from August Blom’s The Mormon’s Victim, a 1911 Danish one-reel film and finds a lot going on in it.

Some students might have trouble recognizing jump cuts. “Sometimes a jump cut …” [25] looks at some examples from the martial-arts action scenes from two of King Hu’s masterpieces, A Touch of Zen and Dragon Gate Inn. These are quite different in look and function from the Breathless examples given in Film Art–and you can clearly see the splices.

Chapter 7 Sound in the Cinema

Faced with innovations in sound technology, we turned to our friend and colleague Jeff Smith. His “Atmos all around” [26] is an excellent introduction to the new system. Unlike most surveys of technology, his piece analyzes in considerable detail how artists use it–here, in Pixar’s Brave.

Chapter 8 Summary: Style and Film Form

Alfred Hitchcock is undoubtedly one of the most frequently taught filmmakers, since his work is not only stylistically elegant, but it’s easy for students to pick up on. One reason for this is that he is fond of flashy set pieces, scenes that are skillfully composed to be the high points of a film. We examine his skill in this regard in “Sir Alfred simply must have his set pieces: THE MAN WHO KNEW TOO MUCH.” [27]

On the other hand, Hitchcock is equally good at subtle touches. Some might consider his 3-D film, Dial M for Murder, to be a bit theatrical, since much of its action is confined to a single set. Yet as we argue in “DIAL M FOR MURDER: Hitchcock frets not at his narrow room,” [28]the director finds many small, creative ways to frame and edit his shots in ways that are purely cinematic.

As we emphasize in Film Art, filmmaking is based on a huge number of creative decisions. During this past year, encounters with two practitioners gave us a chance to learn how they went about making some of these choices. Tim Hunter, director of River’s Edge (1987) and numerous episodes of television series like Twin Peaks and Breaking Bad, visited Madison. “Auteurist on the sound stage” [29]discusses how Hunter plans ahead where he will place his camera, since the fast pace of television production allows little time for such decisions on the set. He also talks about tailoring his style to that of the specific television series he is working on.

In June David visited screenwriter and director David Koepp in his New York office. Koepp is best known for his work with Steven Spielberg, including the scripts for Jurassic Park and War of the Worlds, but he has also directed films. “David Koepp: Making the world movie-sized” [30]discusses how Koepp finds the “Gizmo,” or basic premise, for big blockbusters and how he compresses the plots of best-sellers for the screen. He also talks about narrowing down the many choices available to a filmmaker, creating constraints that will allow him to find the best choices for a given situation–with camera placement again being a basic consideration.

This past year two major contemporary directors died: Tony Scott, director of flashy, violent Hollywood action films, and Theo Angelopoulos, maker of austere, stately dramas about Greek history and politics. We find some surprising stylistic parallels between their work, despite their obvious differences, in “Tony and Theo.” [31]

Chapter 9 Film Genres

Since The Blair Witch Project appeared in 1999, there has developed a sub-genre of horror films masquerading as found-footage documentaries. “Return to Paranormalcy” [32] focuses on the successful series of films that began in 2007 with Paranormal Activity and explores how each successive film has managed to vary the point-of-view conventions in order to maintain audience interest.

This chapter of Film Art contains a “Closer Look” box examining “Creative Decisions in a Contemporary Genre: The Crime Thriller as Subgenre.” Our entry “SIDE EFFECTS and SAFE HAVEN: Out of the past” [33] looks at two more recent examples of this genre, focusing on how their conventions revive and vary conventions that had been introduced in 1940s Hollywood films in this same genre. Here’s a good example of genre conventions coming and going in cycles.

For most people, the name “Kurosawa” conjures up only the venerated Akira Kurosawa, director of classics like Seven Samurai and Red Beard. But there is a younger Kurosawa, Kiyoshi, a contemporary filmmaker. While in Brussels in July, David had a chance to attend a screening of his Shokuzai. In “The other Kurosawa: SHOKUZAI,” [34] David puts Kiyoshi Kurosawa in his historical context and analyzes the film as a combination horror film and crime thriller, as well as including some stylistic analysis.

Chapter 10 Documentary, Experimental, and Animated Films

Shirley Clarke was a major director of experimental and documentary films. Portrait of Jason, her feature-length recording of the recollections and comments of a gay black man was re-released in a restored version last year. “I’ll never tell: JASON reborn” [35] discusses its avant-garde approach to recording its subject’s account of what may or may not be the truth. The entry also details the restoration process, which involved material Clarke deposited at the University of Wisconsin-Madison’s archive, the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research. [36]

Of the five animated features from 2012 nominated for Oscars this year, three were made using the traditional stop-motion technique with puppets: Frankenweenie, The Pirates! Band of Misfits, and Paranorman. “Annies to Oscars: this year’s animated features” [37] discusses them, as well as the computer-generated features, Brave and Wreck-It Ralph.

Chapter 11 Critical Analysis of Films

During the past year we’ve written quite a lot about film analysis. These entries might give some encouragement and suggestions to students embarking on their own critical studies of films.

In June the new online film journal, The Cine-Files [38], interviewed Kristin about her approach to film analysis. The editors kindly allowed us to post the interview, “Good, old-fashioned love (i.e., close analysis” of film” [39]on our site as well. The interview includes discussions as such topics as, “Please tell us about something that couldn’t be understood without a frame-by-frame attention to detail.” It also discusses our recent forays into online video and PowerPoint analysis.

A lot of interpretation of films gets done, by professional critics and students, by fans, and by anyone who gets an idea about a film and offers it to the world. In Film Art, we suggest that valid interpretations of films tend to be based on close analysis of all aspects of the film. Needless to say, not every interpreter does the work of analysis before expounding their ideas. The feature documentary about amateur interpretations of Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining gave us an opportunity to discuss this tendency in “All play and no work? ROOM 237.” [40] Surprisingly, some ideas offered by the subjects of the documentary aren’t necessarily that different from those propounded by professionals.

Christopher Nolan is one of the most admired filmmakers in contemporary Hollywood. What sets him apart? We discuss some of his innovatory tactics in “Nolan vs. Nolan.” [41] The focus is on Insomnia, but with mentions of Magic Mike, Memento, Inception, and The Prestige. The latter is our primary example in Film Art‘s chapter on sound, and this entry might offer useful background material for teachers who show The Prestige to their classes.

For many students, non-Hollywood films can be intimidating to watch and even more so to analyze. “How to watch an art movie, reel 1” [42] offers hints for understanding and discussing art films. The film in question is Jaime Rosales’ Spanish film Sueño y silencio (2013). It hasn’t been widely seen, but one need not have seen the film to understand the analysis of its first twenty minutes. This entry discusses conventions of the art film that might help students in writing their own essays.

Chapter 12 Historical Changes in Film Art: Conventions and Choices, Tradition and Trends

One section of this chapter deals with “The Development of the Classical Hollywood Cinema (1908-1927).” In another new video lecture, “How Motion Pictures Became the Movies 1908-1920,” we deal with the same period on an international level. The lecture traces many of the basic techniques of cinematic storytelling in use in modern cinema back to their origins in this crucial early period. For an introduction to the video, see “What next? A video lecture, I suppose. Well, actually, yeah …” [43]

Of the three major European stylistic movements of the 1920s discussed in Chapter 12, French Impressionism, German Expressionism, and Soviet Montage, Impressionism has traditionally been the most difficult to teach, due largely to a scarcity of prints of films from the movement. Now a group of major Impressionist films have become available on DVD, those made by the Soviet-emigré Albatros production company. In “Albatros soars,” [44] we describe the films and their release in a prize-winning box set from Flicker Alley. We think students would find La brasier ardent intriguing, if puzzling.

David is at work on a book on 1940s Hollywood cinema. Left-over ideas from that project end up as blog entries now and then. These could fit in with the section, “The Classical Hollywood Cinema after the Coming of Sound, 1930s -1940s.” One such entry, “A dose of DOS: Trade secrets from Selznick,” [45] looks at the hands-on approach of David O. Selznick, arguably the most important independent producer of the era. His guidance affected the style of Gone with the Wind, Rebecca, Spellbound, Duel in the Sun, and other classics of the Hollywood system. Another entry [46] considers in-jokes planted in 1940s films.

David has also posted a related essay in the main section of his website, “Murder Culture: Adventures in 1940s Suspense,” [47]dealing with the influence of mystery and detective fiction on films of the 1940s. For an introduction and link to this essay and to several other blog entries on filmmaking of the decade, see “The 1940s, mon amour.” [48]

The final section of Chapter 12 deals with “Hong Kong Cinema, 1980s-1990s.” The recent death of Lau Kar-leung, one of the major martial-arts choreographers and directors of the 1970s and 1980s, led us to post an appreciation of his style and films in “Lion, dancing: Lau Kar-leung.” [49]The final section provides many bibliographical sources and other information on Hong Kong cinema, as well as links to earlier entries on the subject.

Johnnie To is one of the few directors still successfully maintaining the tradition of Hong Kong action films. The latest of our entries on him deals with a recent release: “Mixing business with pleasure: Johnnie To’s DRUG WAR.” [50]

DVDs to consider

At intervals we post round-ups of recent DVD and Blu-ray releases. The titles usually aren’t the big, recent, popular films, but more specialized items put out by companies like Flicker Alley, Eureka!, and Kino that specialize in issuing classic films, often in beautifully restored versions. A lot of these films have never been available on home video before, and they open up new possibilities for teachers who want to broaden their students’ viewing experiences. They’re also titles to recommend to those enthusiastic students who want recommendations for films they can view on their own.

“Classics on DVD and Blu-ray, for a fröliche Weihnachten!” [51] deals mostly with German silent films, including a set of four starring the early superstar Asta Nielsen, and two films by G. W. Pabst: the first release of his debut film, an Expressionist-style work called Der Schatz, and the most complete restoration so far available of The Joyless Street. A new and longer version of Ernst Lubitsch’s Das Weib des Pharao is included, as is a charming Technicolor version of Gilbert and Sullivan’s The Mikado from 1939.

Regular readers are familiar with our annual tradition of naming the ten-best films of the current year but of 90 years ago. For once all the films on our list of “The ten best films of … 1922” [52] are all available on DVD, including a stunning print of Fritz Lang’s Dr. Mabuse der Spieler and the Criterion Collection’s release of the Svenska Filminstitutet’s restoration of Benjamin Christensen’s Häxan (better known in the USA as Witchcraft through the Ages).

As of September 28, Observations on Film Art will be seven years old.

Fantomas (1913).