The Youth of Maxim (Grigoriy Kozintsev and Leonid Trauberg)

Kristin here:

As usual, this end-of-the-year entry has come out early in the next year. I was out of the country for six weeks recently, returning on December 27. It takes awhile to choose ten films, track down copies, watch them, and format the illustrations. For my 1934 list, I complained because I had trouble finding a tenth film. Looking back now, it was a very good line-up. 1935 turned out to be far more difficult. Only a few really obvious films sprang to mind, and the remaining seven are good but not great films. Fritz Lang didn’t make a film that year. Mizoguchi made two films that year, Oyuki the Virgin and The Downfall of Osen. David discusses them in the Mizoguchi chapter of Figures Traced in Light, but he must have watched them in an archive; I couldn’t find anything but unwatchable prints on YouTube.

One problem this year was a lack of decent DVDs and Blu-rays to watch and the take frames from. I try to avoid YouTube, but two films were only available there. Two were only on the Criterion Channel, with no discs available.

At least I can look forward more confidently to 1936. Renoir’s The Crime of M. Lange, Lang’s Fury, Ozu’s The Only Son, and so on. Most of the films below are pleasant entertainment, but hardly masterpieces. I begin with the three best of the bunch, and the rest are in no particular order.

Previous lists can be found here: 1917 [2], 1918 [3], 1919 [4], 1920 [5], 1921 [6], 1922 [7], 1923 [8], 1924 [9], 1925 [10], 1926 [11], 1927 [12], 1928, [13] 1929 [14], 1930 [15], 1931, [16] 1932, [17] 1933, [18] and 1934 [19].

Toni (Jean Renoir)

Toni is an unusual film for Renoir. His earlier films of the 1930s (his La Chienne was on my 1931 list and Boudu Saved from Drowning made the 1931 one) were studio productions with professional actors. In 1956 he wrote of his approach to Toni:

At the time of Toni, I was against makeup. My ambition was to bring the nonnatural elements of the film, the elements no longer dependent on the coincidence of chance encounters, to a style as close as possible to that of daily encounters.

Same thing for locations in Toni, there are no studios. The landscapes and the houses are as we found them. The human beings, whether they are played by actors or inhabitants of Mariques, try to be like the passersby they are supposed to represent: in fact, aside from a few exceptions, the professional actors themselves belong to the social classes, nations, and races of their roles.

The opening of the film, set by a rail bridge by the town of Mariques, near Marseilles, shows immigrants coming from various nearby countries, mostly Italy and Spain, arriving looking for work in the nearby quarry and other industries. Initially the film seems almost like a documentary. One of the workers is Toni, an Italian who rents a room in a boarding house run by a French woman, Marie. The plot develops as he becomes Marie’s lover. He is attracted, however, by a woman at a nearby farm, Josepha. She marries a thuggish supervisor at the quarry, and Toni is resigned to marrying Marie. Despite the real locations and the potential for political treatment of the workers’ lives, the rest of the story is a melodrama dealing with the problems Toni encounters as he is torn between the two women.

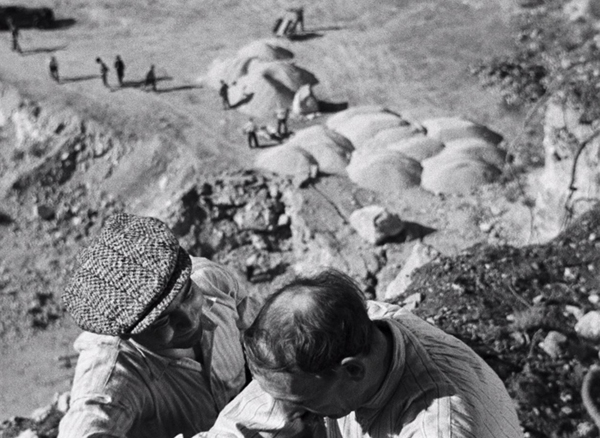

Despite the rather bland settings (the film was shot in the autumn), Renoir manages some striking shots. He occasionally uses depth shots, as with a dramatic high angle as Tony talks with his friend on a cliff at the quarry (above). Another depth shot involves an interior shot through a window, with Marie in bed, barely visible in a gap which David would call “aperture framing.” (See also the bottom, with a depth shot after Marie’s suicide attempt.)

Toni is available on DVD or Blu-ray [22] from the Criterion Collection and streams [23] on the Criterion Channel.

An Inn in Tokyo (Yasujiro Ozu)

Not surprisingly, Ozu has become a regular member of the yearly lists. (That Night’s Wife, 1930; Tokyo Chorus, 1931; I Was Born, But …, 1932; both Dragnet Girl and Passing Fancy, 1933; and Story of Floating Weeds, 1934.) He will no doubt return at intervals at least, as long as this series of entries continues.

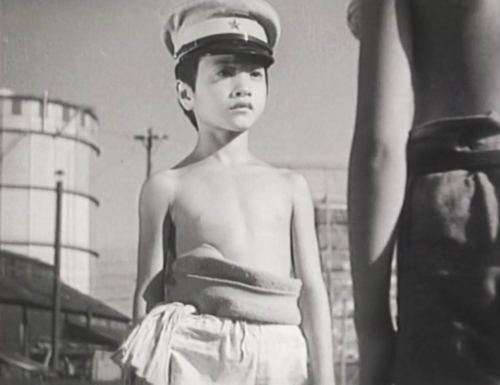

Sound came late to Japan, and An Inn in Tokyo is his last surviving silent film. It’s main character is Kihachi, the same name as that of the father in Passing Fancy and played by the same actor, Takeshi Sakamoto. He doesn’t seem to be the same character, however, since in the earlier film he had one son, and here he has two. They doggedly follow him as the three walk from town to town. Kihachi is looking for a job in the Depression, and although he says he’s an expert lathe operator, he is rejected time after time. He and the boys resort to catching dogs and turning them in at police stations, because an anti-rabies campaign is going on, with rewards offered for dogs brought in. The boys continue to encourage their father, but he becomes increasingly discouraged. Ozu conveys the days that pass almost identically by showing a variety of similar industrial landscapes.

Ozu’s style is fully developed here. The opening with a large empty drum and cuts to the same drum with the family trudging along the road, seen in long shot and from a low camera height. Shot/reverse shot is done by systematically crossing the axis of action, with the framing creating graphic matches created by the characters’ positions. Low camera height and other familiar Ozu techniques are consistently used.

An Inn in Tokyo streams on the Criterion Channel [27] but for some reason has not been released on disc.

The 39 Steps (Alfred Hitchcock)

Around 1970, when I was approaching the end of my undergraduate career, majoring in tech theater, at the University of Iowa. I took a film history course as the only elective I could find that could fit into my schedule. (Film was in the same department as theater and rhetoric.) Other courses followed and lured me into grad school studying cinema.

I had a lot of catching up to do, watching the classics of the canon as it was at the time. No easy task in those days before home video in the form of VHS tapes, which were only beginning to appear on the scene.

I knew I wanted to see Hitchcock’s work, but the number of his films unavailable for viewing in any format, including 16mm (the norm for classroom use) is startling in hindsight. None of the silent films, few of the 1930s ones, and several of the 1950s films, including Rear Window, Vertigo, and the second Man Who Knew too Much, which were blocked from exhibition by rights problems. I read Hitchcock/Truffaut, which had come out a few years earlier; thus I got a sense of Hitch’s career.

Some readers will remember the impact Charles Champlain’s weekly series Film Odyssey when it was shown on public television in 1972. Twenty-six films, which Champlain discussed afterward with directors and scholars. Fritz Lang appeared to talk about M, Annette Michaelson about Ivan the Terrible Part I and Potemkin, Renoir on Jules and Jim, Grand Illusion and The Rules of the Game, and so on. Basically the list was made up with Janus films, the ones we still see on The Criterion Channel and on the Criterion Collection’s discs. I was one of many whose lives were changed by that series, little knowing that in several years I would write my dissertation on Ivan the Terrible and publish it with Princeton University Press (1981). I still treasure the program booklet, provided free on request from Xerox, which sponsored the series.

Among the films was The 39 Steps. The booklet includes excerpts from some of the interviews, but not nearly all. These are the only way one can get information about who the interviewees were. One fan has listed the films and known interviewees on the Criterion Forum [29].) Eight films, including The 39 Steps don’t have this information. My vague recollection is that it was considered the best of the series of six films Hitchcock made in the mid- to late 1930s. (I don’t include Jamaica Inn, which I find unwatchable.) That series was The Man Who Knew Too Much (1934, see last year’s ten-best entry); The 39 Steps; Secret Agent (1936), probably the dullest of them; Sabotage (1936); Young and Innocent (1937); and The Lady Vanishes (1938).

With most of Hitchcock’s films now available in some form, we can perhaps see that at least The Man Who Knew Too Much, Sabotage, and The Lady Vanishes are equal to The 39 Steps. (I haven’t watched Young and Innocent recently.)

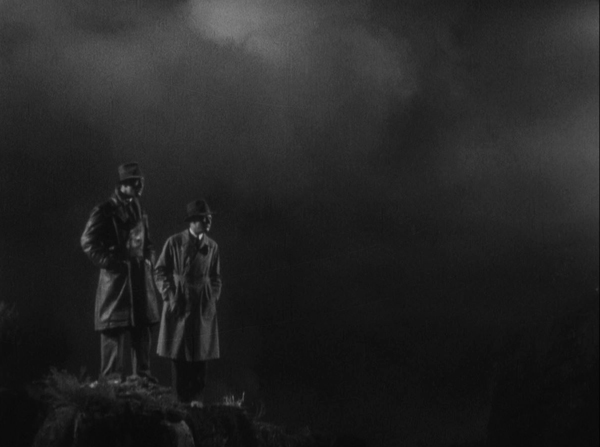

The film has Hitchcock’s usual blend of suspense and humor that characterize many of his films and especially the ones from this period. The Macguffin is a secret that a group of spies are about to smuggle out of the country. Richard Hannay is forced to try and prevent this by a mysterious lady spy on the British side takes refuge in his flat and explains the smuggling plot. We never learn what the secret it, it being a Macguffin, after all. The lady spy is murdered and Hannay is assumed to be the killer and flees from London to Scotland. He continues his attempt to prevent the smuggling, but the real suspense of the film is built around his repeated narrow escapes from the police chasing him. The Scottish landscapes through which he flees are partly short on location, but quite a few shots were done with rather cheap studio sets; Hitchcock managed to give these a strong atmospheric with lighting, as in the frame at the top of this section.

One police encounter ends with Hannay handcuffed to a pretty blonde who has offered to provide evidence against him. This adds the conventional romantic subplot of a couple who hate each other initially and then cooperate to reveal the real murder and spies. It also provides a little mild risqué humor as the two have to pretend to be a honeymooning couple in order to take refuge in an inn (above).

The 39 Steps is available on Blu-ray and DVD from The Criterion Collection [31] and streaming on the Channel [32].

Ruggles of Red Gap (Leo McCarey)

My impression is that Ruggles is not thought of as a significant film within academia, which is a pity, as it is a clever, funny film. It was based on Harry Leon Wilson’s 1915 best-selling novel. (P. G. Wodehouse claimed to have invented his character Jeeves because he felt that Wilson had failed to capture the dignity of English valets.) Ruggles was a considerable box-office success and was nominated for a Oscar as Best Picture. It’s score on Rotten Tomatoes is 100% (among critics, the general populace ranks it at 89%). It played at Il Cinema Ritrovato in a 2015 McCarey retrospective in Bologna.

The plot is based around an English nobleman who through gambling loses his valet, Ruggles, to a nouveau riche couple vacationing in Paris. The wife wants Ruggles to dispose of his new master’s loud clothing (above) and dress him in a more dignified fashion. Doing his duty, Ruggles allows the couple to take him to Red Gap, their small town in Washington. He adheres to his valet’s job, doggedly deferring to his employers by refusing when they tell him to proceed them through doors. Once in Red Gap he gradually grasps the American ideal of all people being equal, becomes a popular citizen of the town, and opens a restaurant.

Ruggles is widely viewed as a screwball comedy, which I think is a fair assessment. It follows the common plot premise of rich people being eccentric, often in regard to working-class people. (A model of such a plot is My Man Godfrey, released in 1936.) It’s very funny, due largely to its excellent cast. Charles Laughton was anxious to show that he had a broader range than the villains and scoundrels whom he had played in his most prominent films.

Ruggles is widely available on a variety of streaming services. The DVD [35] from which I took these illustrations is still available. A British Blu-ray from Eureka! is out of print and seems to be difficult to find and expensive when one does. The frames above demonstrate that in this case a DVD is quite acceptable.

A Night at the Opera (Sam Wood and Edmund Goulding)

I thought that Duck Soup (1933) would be the Marx Brothers sole appearance on these lists. The general consensus is that the Marx Brothers’ uncontrolled madness was toned down by Irving Thalberg when they moved to MGM. In a lean year like 1935, however, A Night at the Opera, while not a masterpiece, isn’t out of place in the list.

True, one must sit through two bland musical numbers. Kitty Carlisle at least can act and sing opera, but Allen Jones and his nasal crooning are pretty intolerable and implausible when he impresses a big opera impresario. Moreover, there are the inevitable piano (Chico) and harp (Harpo) solos, this time delivered to cute little children.

Still, setting all this aside, the film has advantages. Zeppo departed the team between Duck Soup and A Night at the Opera. There are two chaotic sequences that live up to the old Marx style: the famous stateroom scene, reaching its most crowded in the frame above. The lengthy interruption and destruction of the opera performance in the climactic scene is hilarious. Groucho is close to his best here, dominating the non-musical-number scenes with constant ad-libs and mugging.

I watched the Warner Bros. Archive Collection’s Blu-ray [38]. (Amazon is even still selling a VHS tape.) The same version streams on Amazon Prime [39] and other services for a small fee.

Carnival in Flanders (Jacques Feyder)

How many people these days knows much of Jacques Feyder’s films? Silent film lovers may be familiar with his 1922 show feature Crainquebille, and Garbo fans recognize him as the director of her elegant 1929 film The Kiss. La Kermesse héroïque remains his main classic of the sound era.

Set in 17th Century Flanders during the Spanish occupation, the film deals with the reaction of a town in the path of an approaching Spanish military group. Fearful of a attack of rapine and pillage, the men of the city timidly come up with a feeble plan to pretend that the mayor has recently died. Scornful of the plan, the women, including the mayor’s wife, decide to welcome the Spaniards with entertainment, food, and in some cases sexual favors. The Spaniards are delighted, enjoy an night of carousing, and move on in the morning.

Feyder saw the film as a farce, and much of it is quite amusing. Still, the idea of the women saving their town by consorting with the enemy adds a sour undertone to the film. Nevertheless, if one ignores this and take it as Feyder intended, Carnival is an impressive film. The action takes place within an elaborate city set by the great designer Lazare Meerson (above and below). The comic scenes are played by an excellent cast, particularly the major stars Françoise Rosay as the mayor’s wife and Louis Jouvet as a cynical Spanish priest.

I have been unable to track down a disc release still in print, but the film streams on The Criterion Channel [42].

Wife, Be like a Rose! (Mikio Naruse)

Naruse makes his second appearance on the list, after Street without End in 1934. My impression is that a lot of Japanese cinema aficionados view it as his best film of the 1930s.

The plot is handled in an interesting way, with the action falling into two halves. In the first part we meet Kimiko, a modern young woman who claims her salary is bigger than her boyfriend Seiji’s (below). The two bicker and tease each other but are clearly assuming they will eventually marry. Kimiko’s mother, Etsuko, spends her time writing poetry and lamenting the absence of her husband Shunsaku, who has run off with another woman long ago. Kimiko remarks that her mother never paid much attention to her husband. When she sees her father on the street one day, she expects him to visit her and her mother, but he never shows up. Angry, Kimiko takes a train up to a mountain village where her father lives with the other woman.

So far we have seen the situation entirely from Kimiko’s point of view and occasional remarks from Seiji. Once Kimiko reaches the village, she goes into the countryside to see her father. He spends his time panning for gold, hoping to make a better life for his other family, who life a somewhat spartan life. Once Kimiko meets Oyuki, the woman Shunsaku lives with, she realizes that Oyuki is kind and generous and feels guilty about having broken up Shunsaku’s marriage. Although poor, she has been sending money anonymously to Etsuko, money Kimiko had assumed came from her father. The entire situation that had been set up in the first half is turned upside down, and Kimiko finally is convinced that her mother has given him no reason to return and it is better that her father stay as he is.

As usual, the film has echoes of Ozu’s style. The film starts with a shot through a window in an office building (above), a common way Ozu starts his films dealing with characters who work in bland offices. Naruse also uses shot/reverse shots that cross the 180-degree line and creating graphic matches between the two characters, particularly their faces.

He also uses references to American movies, as Ozu does. Here a cover of a fan magazine clearly entitled “Hollywood” (left). Which is not to say that Naruse follows Ozu slavishly. His tracking shots are quite different. In the scene where Kimiko is moved by Oyuki’s description of her happy if spartan home life and her revelation of her sending the money, Naruse uses a tight close-up of the two women, something Ozu would never do.

In a short running time (74 minutes), Naruse leads us to radically change our views in the way that Kimiko does and to sympathize with “the other woman,” who had been vilified in the first half.

Being a sound film, Wife Be like a Rose! is not in Criterion’s Eclipse box set of Naruse’s late silent films, which includes Street without End. The only place I could find it is on YouTube [48] in a so-so print with rather obtrusive large subtitles in black boxes. It’s not available on disc as far as I can tell.

I should add that for mediocre prints like this one, I usually photoshop them, typically boosting the contrast a little and getting rid of any bugs that are present. Wife has a NipponKino logo at the bottom right and little white curved corners, which I also eliminate. The idea is to give a better sense of the filmmaker’s style.

Steamboat Round the Bend (John Ford)

In her excellent new book, John Ford at Work: Production Histories 1927-1939, Lea Jacobs has this to say about the importance of Ford’s actors were one of two vital influences on him: actors and cinematographers:

Obviously Ford’s career may be charted through the stars he worked with and sometimes helped to create. Henry Fonda and John Wayne are the most famous examples, but Victor McLaglen and Will Rogers are much more important for the first half of the 1930s, and their influence on Ford’s œuvre and career remains to be fully explored. (p. 5)

She contributes to that exploration with a chapter on Ford’s three Will Rogers films, Doctor Bull, Judge Priest, and Steamboat Round the Bend. The latter is not a masterpiece on the level of most films that make it to my lists, but Lea assures me it’s the best of the three. I hadn’t watched any of them, so I started backwards and watched Steamboat–not just for this list but in preparation of reading that chapter. (I plan to discus the book in a future blog entry.)

Rogers plays Doctor John Pearly, a snake oil salesman who passes his bottles of Pocahontas as medicine, though it is mainly alcohol (above). This is played for comedy, so that the extremely popular Rogers, with his homespun persona, does not come across as a villain. Apart from making money in this fashion, he decides to overhaul his rundown steamboat and enhance his income with it. When the owner of a fancier boat belittles Pearly’s, the two agree to a bet on a steamboat race, with the winner taking ownership of the other’s boat. A major subplot involves Pearly’s newphew Duke, who shows up with Fleety Belle, whom Pearly initially rejects with scorn as a “swamp girl.” A rapid transformation follows, as a bath and a wardrobe of Pearly’s late wife’s clothes turn Fleety into a spunky, smart young lady whom Pearly admires and even teaches to steer his boat. Duke has been accused of a murder of a man who was trying to force himself on Fleety, and much of the rest of the film involves a search for a witness to the crime who can clear Duke.

The film gives a good demonstration of why Rogers was so very popular. Much of Steamboat has the look of a fairly low-budge film, but Ford pulls out all the stops at the end, with a whole fleet of steamboats participating in the race (more than are visible in the frame below). Naturally Pearly is the one who ends up with two boats, when he runs out of wood and stokes his fire with the remaining stock of Pocahontas–suggesting that he will now give up his old ways and make an honest living.

Steamboat was Rogers’ last film. It was released a month before his death in a plan crash.

Steamboat is available on DVD as part of a set, John Ford at Fox Collection, with all three Rogers films and three other comedies. I haven’t checked the quality of the prints, but it’s a 20th Century-Fox release. Steamboat was earlier also released by itself by Fox. That’s out of print, but there are plenty of copies on eBay. That’s the one I used for the frames above. As far as I can tell, the streaming rights have expired for all the services that used to carry it.

The Youth of Maxim (Grigoriy Kozintsev and Leonid Trauberg)

1935 was not a good year for most of the major filmmakers in the USSR. Eisenstein was struggling with the ill-fated Bezhin Meadow. Pudovkin was accused of formalism for Deserter (1933), and combined with health problems, his next film was not released until 1938. I haven’t been able to find a watchable version of Dovzhenko’s Aerograd, but friend, colleague, and Dovzhenko expert Vance Kepley assures me that it does not belong on a ten-best list.

Kozintsev and Trauberg have been on the list previously (The Overcoat, 1926; New Babylon, 1929; and Alone, 1931).

The Youth of Maxim is the first of three films, The Youth of Maxim, The Return of Maxim (1937), and New Horizons (1939). These were loosely based on the life of writer Maxim Gorky, presumably derived from his fictional set of memoirs, My Childhood, In the World, and My Universities (1913-1923). The films do not reflect Gorky’s actual life, however. The future author had a miserable early life, orphaned at a young age, wandering across Russia from job to job, and even attempted suicide. (“Gorky,” an assumed name, means “bitter.”)

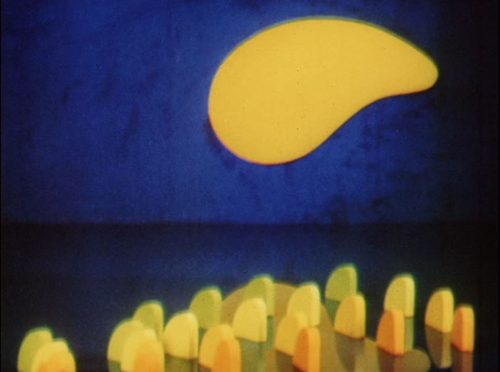

By contrast, in the first film, Gorky is a carefree young man with a factory job and a girlfriend. We first see him singing a cheerful song with his two friends. The year is 1910, but Gorky has no knowledge of workers’ rights or a coming revolution. The arc of the plot is conventionally Stalinistic. The death of one of the friends in a factory accident begins to alert Gorky to the dangers workers are exposed to and the indifference of the owners to such a minor problems. A second death (above) lingers over the workers grief and anger, and Gorky begins to realize the resistance is necessary. Ultimately at the funeral procession for the dead man, the workers treat the occasion as a protest march, watched by the owners and a military presence (see top). When a riot breaks out, Gorky finally commits to the workers’ cause and joins in the fighting, ending up in prison.

This film and the two that succeeded it were both considered acceptable to the regime, and in 1941 the two directors were awarded the Stalin Prize.

The only place I could watch the film was on the RVISION channel on YouTube [52], with subtitles. It’s a so-so print, reasonably good in some scenes and poor in the darker ones, including the lively opening that seems to have echoes of New Babylon.

Two experimental animated shorts in color:

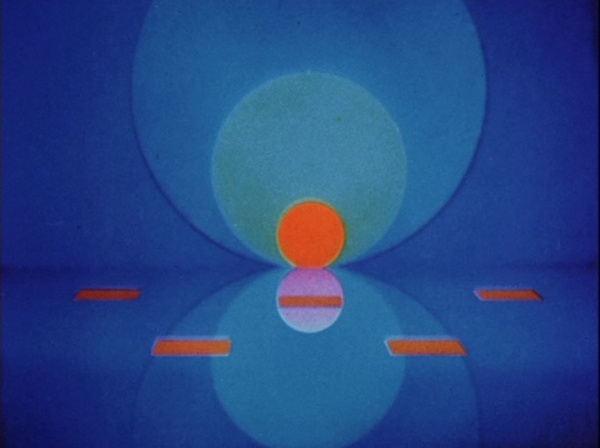

Composition in Blue (Oskar Fischinger)

Fischinger began his career making black-and-white abstract animated film synchronized to musical pieces. A group of these Studies were included in a section on experimental cinema in my 1930 list. During the 1930s Fischinger participated in the development of a color system called Gasparcolor, which he first used in one of his ads for Muratti cigarettes, Muratti geift ein (1934) and some animation tests. His first exhibited experimental film using the system was one of his major animated works, Komposition in Blau, at four minutes. It is done in stop-motion rather than with drawings. Most of the little shapes that move about via stop-motion are objects.

The film was shown at a theater in Los Angeles, leading Paramount to hire Fischinger. His move to the US was permanent. His work there culminated in his most ambitious project, Motion Painting No. 1 (1948).

Composition in Blue is available from the Center for Visual Music [55] on one of the two discs of his work: Oskar Fischinger: Visual Music.

A Colour Box (Len Lye)

Coincidentally, in 1926 New Zealand avant-garde artist Len Lye had moved to London and in the 19302 started work for John Grierson’s Film Unit within the General Post Office. His first two four-minute color shorts, both made in 1935, were Kaleidoscope and A Colour Box. Rather than using stop-motion to manipulate colorful objects, he painted shapes directly onto clear 35mm film. The result was a pair of abstract animated films that ended with a brief passage of words and numbers aimed at promoting the G.P.O.

Both shorts were made using a different early system called Dufaycolor. It seems to have had a narrower range of colors than Gasparcolor, which Lye switched to for his next films, including the marvelous Rainbow Dance (1936)–which might well make it to next year’s list.

A DVD collection of Lye’s shorts called rhythms has been sold in the past by the Center for Visual Music, but the shop lists it as sold out, which seems to be permanent. Canyon Cinema [57] has the same DVD for sale.

Thanks to Vance Kepley, Lea Jacobs, and Ben Brewster for help with this entry.

The quotation from Renoir is from the notes included in the Criterion disc of Toni, which also contains a useful essay by Ginette Vincendeau

Toni