The Cure (1917)

Kristin here:

One occasional feature of our blog has been to point out new releases on DVD and Blu-ray, especially of titles that haven’t gotten much publicity. Some of these are easily available at major sources like Amazon, while others have to be ordered directly from their publishers, often abroad. But if you have a multi-standard player, don’t hold back. Ordering from abroad isn’t as intimidating as it might seem. Many sites have English-language sales pages.

We’ve done a lot of these entries by now. You can find them through the DVD category in the list at the right, but I thought it might be useful to give links to all of them here, with brief indications of what each deals with. Some of the DVDs are probably out of print by now, but in this era of eBay and third-party sellers, one can usually track down such things. Then I’ll give a rundown on some recent releases.

The first was Dispatch from the Land of the Long White Cloud [2], written when David and I were fellows at the University of Auckland in May, 2007. I discussed some of the DVDs of New Zealand films that I had found in stores there. Some are famous, some obscure.

2008 was either a great year for DVDs or we just had more time to deal with them. On January 18, I posted Tracking down Aardman creatures [3], a guide to the classic animated films of Nick Park, Peter Lord, and their colleagues at Aardman. At the time it was probably the most complete information one could get on these films. Of course, Aardman has gone on to make other films and TV series, but this was the studio’s golden age. On February 1, I described with two boxed sets dealing with early sound films in All singing! All dancing! All teaching! [4]As the title implies, these are a boon to film teachers, as well as buffs and researchers. In Coming attractions, plus a retrospect [5] (June 6), David discussed the release of Robert Reinert’s very peculiar silent film, Nerven, and in Summer show and tell [6] (July 28, 2008), he briefly dealt with a miscellaneous set of DVDs and books that we discovered during our annual visit to Il Cinema Ritrovato and other destinations. On December 10, in Preserving two masters [7], I discussed the restored version of Lubitsch’s Das Weib des Pharao (which at that point wasn’t out on DVD) and a Walter Ruttmann set.

2009 was a pretty good year, too. On February 18, I wrote about the Flicker Alley release of Abel Gance’s influential classic La roue, including historical background on the film, in An old-fashioned, sentimental avant-garde film [8]. David took the occasion of of a new Criterion boxed set to summarize the work of the fine Japanese director Shimizu Hiroshi [9] (May 9). On May 21, in Forgotten but not gone: more archival gems on DVD [10], I described two major boxed sets, one of Lotte Reiniger’s lovely but seldom-seen fairy-tale shorts, and one of early Belgian avant-garde cinema–and yes, the early Belgian avant-garde cinema includes some important titles. On August 2, David again caught up with the mixed batch of DVDs and books picked up in Europe over the summer or sitting in the stack of mail upon his return, in Picks from the pile. [11] Finally, on November 9 I discussed the British release of Dreyer’s Vampyr with a very worth-while commentary track by Guillermo del Toro, who said, among other things, “I am not Carl Dreyer, and I should shut up.” [12]

In February of 2010, I wrote DVDs for these long winter evenings [13], dealing with three sets with the work of three crucial filmmakers: Georges Méliès, Ernst Lubitsch (most of the German features), and Dziga Vertov. In October, it was More revelations of film history on DVD [14]: a documentary on Veit Harlan, a new series of Soviet silent films, and the Flicker Alley set of Chaplin’s Keystone films. (For the follow-up, see below.) On November 28, Silents nights: DVD stocking-stuffers for those long winter evenings [15] covered little-known Norwegian and Danish silents, a rare Expressionist film, Ford’s The Iron Horse, hilarious Max Davidson comedies, and the Kalem company.

For some reason it was a full year before we posted more DVD coverage in our second Christmas-gift-themed entry, Classics on DVD and Blu-ray, in time for a fröliche Weihnachten! [16] (November 29, 2012). It probably took us that long to get through all the discs we picked up in Bologna and elsewhere. The title reflects the heavily German coverage: early Asta Nielsen films, Pabst’s first feature, the release of Das Weib des Pharao on DVD and Blu-ray, as well as the 1939 Hollywood version of The Mikado.

Earlier this year, on June 20, we posted our most recent DVD/Blu-ray entry, Recovered, discovered, and restored: DVDs, Blu-rays, and a book [17]. It deals with a burst of releases of Norwegian silent films, a new entry in the “American Treasures” archive series, and some American films, famous and obscure.

Now more DVDs are piling up, and the time seems ripe for a third set of holiday-present suggestions, to give or hope to receive.

Caligari, restored at last

In our survey of the ten best films of 1920 [19], I mentioned that Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari was one of the films that lured me into film studies during my undergraduate days. I know it very well. I was tempted to go to one of the screenings of the recent restoration this year at Il Cinema Ritrovato, but it was opposite other films I had never seen before, so I passed it up. Luckily now Kino Lorber [20] has brought that restoration out on DVD and Blu-ray (sold separately).

The negative of Caligari does not survive in its entirety, but the restoration has taken the usual steps to fill it in and provide authentic tinting. The information comes from titles at the beginning of the DVD print:

The 4K restoration was created by the Friedrich-Wilhelm-Murnau-Stiftung in Wiesbaden from the original camera negative held at the Bundesarchiv-Filmarchiv in Berlin. The first reel of the camera negative is missing and was completed from different prints. Jump cuts and missing frames in 67 shots were completed by different prints.

A German distribution print is not existing. Basis for the colours were two nitrate prints from Latin America, which represent the earliest surviving prints. They are today at the Filmmuseum Düsseldorf and the Cineteca di Bologna.

The intertitles were resumed from the flashtitles in the camera negative and a 16mm print from 1935 from the Deutsche Kinematek-Museum für Film und Fernsehen in Berlin.

The digital image restoration was carried out by L’Immagine Ritrovata-Film Convservation and Restoration in Bologna.

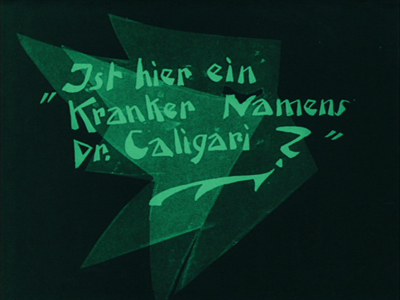

The images are definitely clearer, with more detail visible than in prints I have seen before, and the film runs more smoothly. An inauthentic intertitle has been removed. In most prints, when the grumpy town clerk hears that Caligari wants a permit to exhibit a somnabulist, he calls him a “Fakir” and turns him over to his underlings to deal with. That title is now gone, and it’s clear that Caligari is annoyed at the man’s disdainful attitude rather than a specific insult. The intertitles have their original jagged, Expressionistic graphic design (see above) rather than the plain backgrounds used in many prints hitherto available.

There are optional English subtitles. The modernist musical track fits well with the film.

The supplements include a short essay which I provided and a documentary, Caligari: How Horror Came to the Cinema. The restoration is also available from Eureka! [21] in the United Kingdom, with a different set of supplements and with DVD and Blu-ray sold together.

Flooded by flickers

If you want a lot of good laughs and have 1005 minutes to spare, Flicker Alley’s “The Mack Sennett Collection Volume One” [22] offers 50 restored shorts which Sennett acted in, wrote, directed, and/or produced. (This 3-disc set is available only on Blu-ray.)

The films are presented in chronological order, starting with a 1909 comic short directed by D. W. Griffith at American Biograph and starring Sennett, The Curtain Pole. Two comedies directed by Sennett at American Biograph follow. In 1912 he founded Keystone, represented starting with The Water Nymph (1912) and ending with A Lover’s Lost Control (1915). In 1915 Sennett became one of the three points in the Triangle Film Corporation, along with co-founders Griffith and Thomas Ince. Keystone continued operating as Triangle Keystone, and films from that production unit from 1915 to 1917 are included. At that point Sennett went independent as Mack Sennett Comedies, making mainly two-reelers, beginning in this collection with Hearts and Flowers (1919) and running to The Fatal Glass of Beer (1933). See here [22] for a complete list of titles. Each of the three discs contains a group of films as well as a set of bonuses at the end.

Sennett built a team of excellent comedians, including at various points Ben Turpin, Chester Conklin, Charlie Chaplin, Ford Sterling, Wallace Beery, Louise Fazenda, Mabel Normand, and others. The action typically moves at a breakneck pace, and the editing is similarly fast. Being able to go back and watch some of these routines again, perhaps in slow motion, is ideal for making sure you catch every throw-away gag.

A Clever Dummy shows off the dexterity of the cross-eyed Turpin. Two inventors build a mechanical dummy, modeling “him” on the janitor played by Turpin. At first the dummy is a rather cheap-looking fake, but Turpin plays him in some scenes and the janitor in others. Then he decides to masquerade as the dummy, and his antics persuade some vaudeville agents to buy him for their show (left below). Once in the theater, he defies a stagehand’s (Conklin) efforts to make him stand quietly (right):

Savor these a few at a time, and you’ll have entertainment for months to come.

Of course, some of that 1005-minute total comes in the bonuses. There are newsreel and television appearances by Sennett, including “This Is Your Life, Mack Sennett” (1954) and a half-hour radio appearance on the Texaco Star Theater in 1939.

Back in 2007, we posted an entry called Happy Birthday, Classical Cinema! [25], where we explained how the guidelines and techniques that came to underpin what we now call classical Hollywood cinema came together in 1917. At the end we offered a list of the ten best films of that year, and thus inadvertently our annual ninety-year celebration, “The ten best films of …” came into being. On it were two Charlie Chaplin films, The Immigrant and Easy Street.

They were both made during the third phase of Chaplin’s career, when he had left Keystone and gone first to Essanay and then to Mutual. Those who find the pathos in many of Chaplin’s films from the 1920s onward might plausibly consider his Mutual period to be the height of his career. The twelve films are not all equally brilliant, however. One watches Chaplin developing a better sense of story-telling to go with the slapstick. The Rink comes across as two one-reelers stitched together. In the first half having Charlie does a fairly conventional waiter schtick, but when he visits a rink on his lunch-hour, the films moves into high gear as he performs a dazzling set of moves on skates:

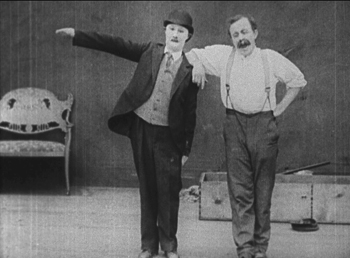

Other films show Chaplin learning to make a sustained, tight story built of non-stop gags, none more skillfully than The Cure. An alcoholic forced into a sanatorium evades all attempts to make him shape up while charmingly defending the heroine from an offensive, gout-ridden villain (see top, where all involved briefly strike a pose).

Flicker Alley has released a steelbox commemorative set of five discs, two Blu-ray and three DVD, to celebrate the centenary of Chaplin’s first appearance as the Little Tramp–though of course that appearance had been made at Keystone.

For a list of film titles and bonus features, see here [27].

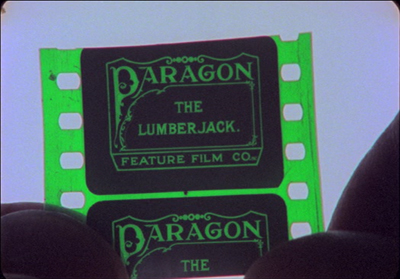

If these sets contain some of the most famous films and performers of their day, another recent Flicker Alley release, We’re in the Movies: Palace of Silents & Itinerant Filmmaking [29], turns to some of forgotten and obscure offerings of the silent era: films made in small towns by independent regional producers, using local citizens for their casts. Earlier this year, David wrote about Wheat and Tares [30], a 1915 film made in his home town by the Penn Yan Film Corporation. That’s not one of the locally made films included in We’re in the Movies, but this two-disc set (both DVD and Blu-ray) does contain The Lumberjack, a short film made in Wausau, Wisconsin and discovered in the early 1980s by Stephen Schaller, then a graduate student in film studies here at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Schaller didn’t just discover the film. He created a lovely, poignant documentary, When You wore a Tulip and I Wore a Big Red Rose (1983), about the making of the film and the history of the one print and how it survived. He tracked down and interviewed several elderly people who had been involved with its making. These included Florence Gilbert Evans, the only surviving cast member, and relatives and friends of others “actors.” At intervals throughout the film, he interviews Louise Elster, who had accompanied silent films on piano in local theaters. She provides a lively commentary on such accompaniments and plays examples as skillfully as she must have done in the day. (Modern-day silent-film accompanists might find many tips from this documentary.)

The only problem with the film is that no identifying titles are superimposed to tell us who these people are, and often their names are not mentioned in the interview excerpts included. One has to struggle at times to figure out who the speakers are and what they had to do with The Lumberjack. Names are only given in the final credits, and even then their connections to the film are not specified. Still, the story of the film’s making comes together clearly enough.

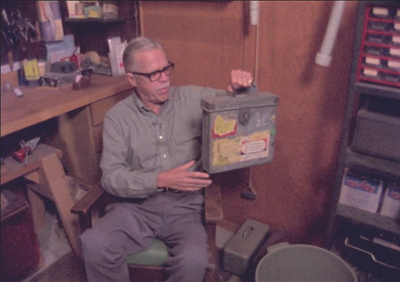

Schaller reenacts the finding of the film itself in a scene with Robert S. Hagge. Hagge, who apparently worked at the Grand Theater, where the sole print resided until 1946, when he took it to his home:

The poignancy of The Lumberjack‘s history emerges gradually as we get to know those involved and their histories. One of the producers was accidentally killed during a quarry explosion staged for the film. Settings shown in the movie are compared with the current appearances of the same places, with some beautiful old buildings preserved and others replaced by bland modern structures. There is a hint that the making of the film created an excitement that transformed the lives of the Wausau citizens involved. When You Wore a Tulip and I Wore a Big Red Rose illustrates the power of even the most modest of films and the inevitable losses caused by the passage of time.

The set also includes a 2010 documentary, Palace of Silents: The Silent Movie Theater in Los Angeles, devoted to a theater built in 1942 and dedicated for over 68 years to showing silent films. The rest of the contents are The Lumberjack and other early local films.

These films strike me as an excellent way of intriguing students and film fans about the silent era of the movies.

Oktoberfest as seen through the movies

I was somewhat surprised to see the new two-DVD set in the Filmmuseum München series: Oktoberfest München 1910-1980. It’s an interesting approach, gathering together the surviving films about a single annual event, Munich’s famous Oktoberfest. As the accompanying booklet points out, the Oktoberfest was a venue where early traveling exhibitors set up their tents to show movies, though little documentation of these shows survives. No one knows when the first films about or set at the festival were made. The earliest one to survive is from 1910.

Oktoberfest was and is more than beer-drinking. There are parades, rides, and various fairground activities as well.

To many film historians, one of the attractions of this collection will be a film starring the comedian Karl Valentin, Valentin auf der Festwiese. The nominal plot involves Valentin taking his wife to the festival while planning to meet his mistress there and sneak away. This story gets shunted aside for most of the film’s length, however, as the couple wander through various sideshow tents. We see their grotesque reflections in a fun-house mirror (above), and the camera perches in a ferris-wheel seat to record the long-delayed confrontation of wife and mistress.

One curiosity of the set is a 3D film from 1954, Plastischer Wies’n-Bummel. The analglyph 3D glasses (red and cyan) required for the effect are included in the set. I found it something of an effort to resolve the 3D in many shots, but there are some dramatic depth effects involving balloons and some fairground swings that work quite well:

The booklet is in German, English, and French, and there are optional subtitles in English and French. The DVD set can be ordered online here [34].

Making a list, Czeching it twice

When we were in Prague [35] this summer, Michal Bregant, head of the National Film Archive, gave us some books and DVDs related to early Czech animation.

One was a catalog published by the archive, Czech Animated Film I 1920-1945 (2012, bilingual in Czech and English), with a short historical introduction and descriptions of all the known films of the period. It relates to a two-DVD set, Český animovaný film 1925-1945 (Czech animated film). This delightful collection contains 30 shorts and has optional English subtitles. Some of the cartoons are outright imitations of American series of the day, such as Hannibal in the Virgin Forest (1932), clearly inspired by early sound cartoons from Disney and Warner Bros.:

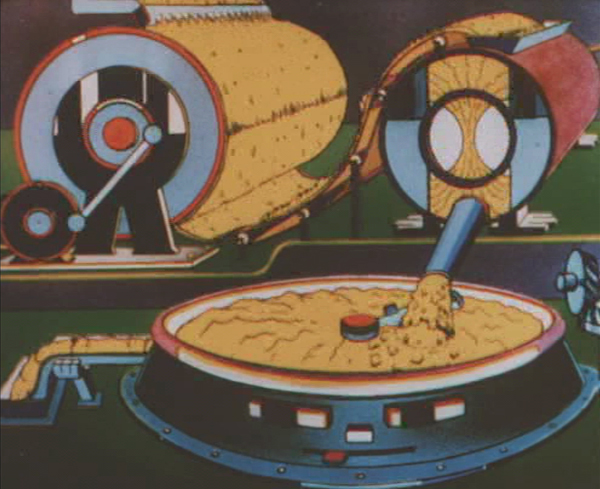

There are also two early György Pál (later aka George Pal) cartoons. Many of the shorts, though, are advertisements. As in other countries where major filmmakerss like Len Lye were doing inventive work for ads, Czech animators came up with some amazing images. Margarine never looked as good as in Irena and Karel Dodal’s 1937 Gasparcolour short for the Sana brand, The Unforgettable Poster (see bottom).

The Dodals were the most important Czech animators of this era, as is shown in a well-illustrated biography, The Dodals: Pioneers of Czech Animated Film, by Eva Strusková (published by the National Film Archive in 2013). It’s in English and comes with a DVD. (There is some overlap between its contents and those of the two-disc set.)

Both are musts for animation experts and fans. The Dodals is available from Amazon [37]. The DVD set won as “Best Re-discovery 2012/13” at the Il Cinema Ritrovato awards [38] last year. It and the catalog can be ordered directly from the National Film Archive website [39] or from a specialized cinema shop in Prague, Terry Posters [40] (this link takes you to the English-language version of the site).

The Unforgettable Poster (1937)