24 Frames (2017).

DB here:

It might seem an act of vandalism. To overwrite one of the world’s most famous paintings, the elder Pieter Bruegel’s Hunters in the Snow, with digital effects could be condemned as vulgar at best and scandalous at worst. In the lower left, we see a dog pissing on a tree. Yet no one ever accused the late Abbas Kiarostami of bad taste. Of weirdness, yes: His Lumière tribute [2] (1995) consisted of a close-up of a frying egg.

Eggs aside, Kiarostami’s experiments mostly have a stubborn stringency. He made a film wholly out of reaction shots, and another out of static takes of landscapes. Yet neither was an arid exercise. Shirin [3] (2008) yielded poignancy as it let us study women responding to a romantic spectacle (film? theatre piece?). The minimalist Five Dedicated to Ozu [4] (2003) was at once meditative and sensuous, speckled with moments of relaxed humor (the parade of the ducks) and building to a curious suspense, as we stare at brackish water trembling in a downpour.

So when the first segment of Kiarostami’s 24 Frames (2017) decorates Bruegel’s masterwork, we ought to expect that something’s up. The explanation offered in the film’s prologue is that the filmmaker is curious about what happens around the instant portrayed in the image.

For 24 Frames I started with famous paintings but then switched to photos I had taken through the years. I included about four and a half minutes of what I imagined might have taken place before or after each image that I had captured.

This declaration, apparently opposed to Cartier-Bresson’s doctrine of the “decisive moment,” [5] leaves creative wiggle room. Kiarostami and his colleagues used digital manipulation to alter his stills, adding layers of figures and movements.

But how do we determine the punctual instant of each of the twenty-four shots? What’s the before or after? Many shots contain several moments of pause that might be the original frozen moment, but Kiarostami doesn’t give them special emphasis. After the Bruegel, we get twenty-three gradually changing natural scenes, nearly all mini-narratives based on stasis, rhythmic cycles, hesitations, and bursts of action. Five showed Kiarostami venturing into the territory of Structural Film, and especially the open-air tendency mastered by James Benning [6]. With 24 Frames we get that monumental impulse recast by photorealistic animation: landscapes teased into little stories by the miracle of rendering, mo-cap, and drag-and-drop.

The birds and the beasts were there

The Bruegel is defaced for a reason. The original painting lays out strategies that the following sequences will pursue. Human bodies will play a subsidiary role; they appear in only two sequences, and, like Bruegel’s hunters, they are mostly turned away from us. We’ll also see snow, birds, dogs, trees, a scraggly bush, and water (the frozen pond). Just as important, Bruegel’s composition warns us how to watch. He draws our eye into the distance, and there lots of tiny figures will grace the scenes ahead.

Kiarostami’s decorations insert more previews. He introduces a herd of cows, blatantly fake falling snow, smoke that prepares us for mist and cloud formations. Dogs and birds are set into motion and given sounds; we’ll spend a lot of time tracking these vagrant creatures, and their cries will help us navigate the frames. The revised painting becomes a matrix of pictorial and auditory motifs that will be combined and varied throughout the movie.

Eventually the landscapes will include a wider menagerie, including lions and horses. At one point a duck seems to size up a possible mate, who approaches from the distance.

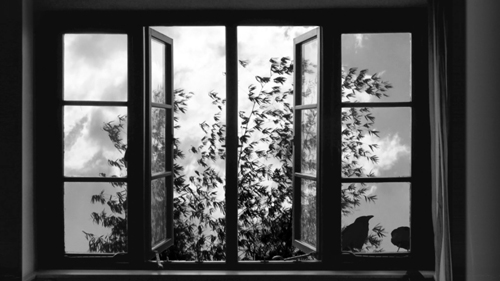

As here, most shots are centered, with the primary action taking place in the central third and sometimes accentuated by an aperture. The apertures often get geometrical. After several open landscape shots, the sixth sequence introduces a major compositional formula–the grid, typically a window, that will striate and cross-hatch our view. It yields a sort of Advent-calendar effect, as we follow birds or beasts hopping from one cell to another.

More variation: Most of the shots are planimetric [9]. The camera is fixed at right angles to a background plane, and figures move horizontally. As the film goes along, though, an oblique angle may show up, as with the duck courtship. Kiarostami applied planimetric framing brilliantly in Through the Olive Trees (1994), but there too it interacted dynamically with less rigid compositions.

Maybe this is Kiarostami’s real Lumière homage. As in the earliest staged films, the single shot is given a simple arc. Figures arrive in the frame, do something, then depart. But sound is tremendously important too. Quiet activity is interrupted by brusque action–too often, a gunshot. More than you might expect, violence provides a spike of action before calm returns.

What holds these crisp, gorgeous shots together? Pairings, for one thing. The creatures we see often become couples. Lions mate, birds scrap with each other, ducks flirt, deer double up, and one gull mourns a fallen companion. Yes, I’m indulging in anthropomorphism. This movie firmly encourages you to try mind-reading Nature’s kingdom.

There’s a trace of surrealism. Some dreamlike images, impossibly hard-edged, are reminiscent of Rousseau. Sheep in a snowstorm huddle while a dog stares out at us and a wolf prowls in the distance. You might think of Paul Delvaux when you see a balustrade that has been built athwart rolling surf, as gulls squat placidly on the poles beyond.

Not least, I think, Kiarostami is responding to one problem of digital cinema–the way that a fixed digital shot makes certain portions of the frame go dead. Photographic film keeps the whole frame nervous, thanks to its teeming granular structure, but image compression simply reiterates “unchanging” information until something moves. When an area doesn’t harbor motion, it looks like a slice of stillness.

Kiarostami exploits this feature of the medium. Again and again, his image seems preternaturally frozen, a nature morte, before it twitches back to life. The effect, to recall his before-and-after idea, is of a still image reanimated. An inert animal seems dead to the world before we detect a breath or a shift of position. The most striking example seems to me the soft silhouette of a bird, a mere lump for seconds on end.

Rudolf Arnheim [13] would have loved the fluid play of Gestalts that this simple composition arouses.

To show you more would spoil the pleasures of this delightful, melancholic, rapturous film. Let’s just say that it ends with a human figure slumped over and turned from us while the wind shakes trees outside a window. Warmth and drowsiness inside, a mild tempest outdoors. But in that same shot, a radiant human face, brought to slow-motion life, turns to us before it surrenders to a kiss. The fact that the face belongs to Teresa Wright, in one of the greatest films of the 1940s, ends Kiarostami’s career on a note of gentle jubilation.

Thanks to Brian Belovarac of Janus Films [14] for help with this entry. Thanks as well to Jim Healy, Mike King, and Ben Reiser of the Wisconsin Cinematheque [15].

24 Frames is being circulated to theatres and museums; please try to see it on the big screen, where all the little details can pop out at you. Eventually, it will show up on disc and FilmStruck [16]‘s Criterion Channel [17].

For background on the making of the film, see the Janus press page [18]. Imogen Sara Smith offers a sensitive appreciation in “In Our Time: Abbas Kiarostami’s 24 Frames” on the Film Comment site [19]. For more on Kiarostami, including Certified Copy [20] (2010), see our blog’s tag [21]. I discuss his planimetric approach in Through the Olive Trees in On the History of Film Style [22], soon to appear on this site in an updated pdf.

24 Frames.