Raining in the Mountain (Hu Jinquan/King Hu, 1979).

DB here:

Thanks to friendly distributors, our University of Wisconsin–Madison Cinematheque [2] has sustained itself with virtual screenings every week [3]. Coming up is one of King Hu’s most marvelous movies, Raining in the Mountain. In tribute, I joined Mike King to talk about it in the Cinematheque’s ongoing podcast series [4].

Best of all, thanks to Film Movement [5], you can watch the film through our Cinematheque’s virtual cinema!

For a limited time, the Cinematheque offers a limited number of opportunities to view Raining in the Mountain at home for free. To receive instructions, send an email to info@cinema.wisc.edu [6] and simply include the word RAINING in the subject line. No further message is necessary.

Now, why should you watch it?

Well, it’s one of the most visually splendid Chinese films ever made. The Buddhist monastery that serves as the setting was actually assembled by editing together several South Korean locations, all majestic. Add in the brilliant color design and costumes of vibrant splendor, and you get a spectacle that David Lean would kill for.

Among this pageantry we find a cast of rogues, supple-spined thieves, selfish and lustful monks, and a couple of wise elders who see through the vanities of this world. A splashy finish is provided by a bevy of cascading courtesans wielding dazzling crimson and gold sashes–handy for trussing up a thief who has anger issues.

Key scenes take place in the monastery library, but the filmmakers were forbidden to shoot there. In a weird echo of the movie’s plot, the monk in charge was bribed and the crew stole the shots they needed. The footage was whisked off to Seoul, but the stratagem cost the producers a few days in custody.

The plot, as Mike and I discuss, is really three stories in one. There’s a heist scheme, in which a plutocrat and a general compete to steal a rare scroll. There’s a political intrigue, as monks jockey to succeed the retiring abbot of the monastery. And there’s a redemption arc, centering on an unjustly convicted prisoner who struggles to get on the path of righteousness. Much of the film is an attack on worldly selfishness. Even in the monastery, the monks are obsessed with money and have to be forced to do honest work. It’s a film about who deserves power, and right now, in our America, it’s welcome to see pragmatic humility rewarded.

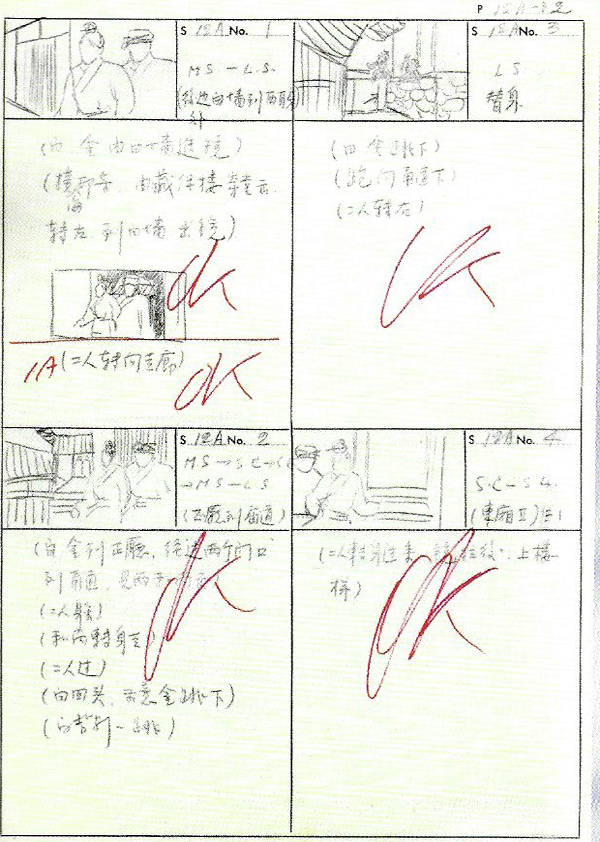

King Hu didn’t finish that many films. He took months to research his projects, and his meticulous planning of costumes and sets made him a slow worker. Unlike many Hong Kong directors, he prepared storyboards and worked out his compositions carefully. As he completed his shots, he checked them off with an “OK,” like the American filmmakers of the silent era.

The connection isn’t accidental. Like a silent filmmaker, Hu had a pictorial intelligence that conceived scenes shot by shot, without the pointless flourishes (arcing camera, slow track-ins) that today’s filmmakers are addicted to. He’s a fast cutter, but his locked-down compositions give you time to see everything.

As a result, Raining in the Mountain is not your typical martial-arts movie. For one thing, what usually counts as action–an aggressive fight, involving punches and kicks–doesn’t come along for an hour. In our conversation, I argue that King Hu replaces fights with zigzag chases, evasions, and hide-and-seek maneuvers. The geography of the monastery gave him vast opportunities for booby-trapped compositions. Figures and faces pop in and out of doorways, corridors, and windows.

The film is designed for the big screen, where details can blossom in distant crannies. So on a monitor (forget the tablet, the laptop, and the phone), you have keep your eyes peeled. While the two thieves drop into a passageway and race into the distance. . .

…a peekaboo framing gradually reveals why they’re hiding: a monk in blue emerges (tiny) in the ledge above them,

The spaciousness of the setting seems to have nudged Hu to try leading our attention to tiny bits of action in the anamorphic frame. Watch how he stages Chang’s preparation for a knife attack in a long shot. Gold Lock is crouching on the left, watching, like us, for the glint of Chang’s blade.

No close-ups are necessary. Hu trusts that we’ll keep up.

As usual in King Hu, there’s a quiet jubilation in watching the calm confidence of fighters leaping from room to room, hopping into a niche, or backflipping under a porch. Hu favors a slow buildup, capped by percussive bursts of action in rhythms recalling Beijing Opera. He cares less about traditional martial arts than about finding ways to create uniquely kinetic dramas of honor, heroism, and protection of the innocent. For him, combat is a staccato dance, and conflict is a test of moral rectitude.

As Mike points out in our conversation, King Hu looms ever larger in film history. A firm line runs from A Touch of Zen to Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (2000) and Hero (2002), and on to Goodbye, Dragon Inn (2003). Tsui Hark’s swordplay films, especially The Blade (1995), owe a great deal to King Hu. (Not to mention John Zorn’s ear-bleeding album [14] dedicated to the director and his incandescent female star Xu Feng.) King Hu remains one of the most original and engaging filmmakers in world cinema.

Film Movement’s site provides a trailer [15] for Raining in the Mountain.

Thanks to Mike King and Ben Reiser for arranging the podcast, and Jim Healy and Pauline Lampert for coordinating so many superb programs under difficult conditions.

A Touch of Zen (1971-1972), which took three years to make, is King Hu’s official classic, and it displays many of his virtues. It’s now easy to see. (There’s a splendid Criterion disc [16], and it streams on Criterion [17] and on Amazon Prime [18].) But don’t neglect his breakthrough Come Drink with Me [19] (1966) and his other “inn films,” Dragon Inn [20] (1968; also Criterion Channel [21] ) and The Fate of Lee Khan [22](1973; streaming here [23]). Perhaps his most dazzling experiment in action cinema is The Valiant Ones (1975), but I don’t know of any good copies on disc or elsewhere. I’m less enamored of Legend of the Mountain [24] (1975), a ghost story, and All the King’s Men (1982), a tale of court intrigue, but it’s possible I’d like them more if I saw them now.

For more on King Hu, precious documents, essays, and recollections are available in Transcending the Times: King Hu and Eileen Chang [25] (Hong Kong International Film Festival, 1998) and King Hu: The Renaissance Man (Taipei: Museum of Contemporary Art, 2012). The storyboards above come from the Hong Kong volume. I recommend Steven Teo’s deeply informed books on Chinese film, particularly Hong Kong Cinema: The Extra Dimensions, [26] Chinese Martial Arts Cinema: The Wuxia Tradition [27], and his monograph King Hu’s A Touch of Zen [28]. Hubert Niogret’s fine biographical study of King Hu is on the Criterion Channel [29].

I discuss King Hu’s work in Planet Hong Kong: Popular Cinema and the Art of Entertainment [30], in the essay “Richness through Imperfection: King Hu and the Glimpse,” in Poetics of Cinema [31], and in other entries on this site. [32]In the podcast with Mike, I mention Hu’s ingenious method of making swordfighters disappear and reappear; this entry [33] explains how he does it and includes a clip.

Raining in the Mountain (1979).