The Goetz and Goetz Junior Theatres, Monroe, Wisconsin, 1936.

DB here:

Eighty years ago the Goetz Theatre of Monroe, Wisconsin opened its doors. Last Sunday it screened the last 35mm prints it will ever show. On Tuesday, it became a digital cinema.

I sometimes find myself wishing I had been alive and sentient when exhibitors migrated from storefronts to dedicated venues in the 1910s, when they wired silent-movie venues for talkies (late 1920s-early 1930s), or when they converted to widescreen in the early 1950s. (For this last change, I was around but not sentient.) Think of all I could have learned about the stuff I study at a long remove now. Today I’m living through another time of technological upheaval, so I’m trying to catch up with it.

There are about 39,000 screens operating in the US, and about half are controlled by five major chains [2]: Regal Entertainment Group, AMC Entertainment, Cinemark, Carmike, and Rave. Most of the screens are in population centers and are housed in multiplexes, which introduced economies of scale to the exhibition sector. Those economies make it relatively easy for the big chains to convert to digital. As a follow-up to my post on digital conversion at a local AMC multiplex (here [3]), I wondered how the process affects a small-town exhibitor. After all, thousands of screens across the country belong to regional circuits or are mom-and-pop operations.

So I went to Monroe.

Local boys make good

Wisconsin is more than cheese and beer, but both have shaped the history of Monroe [6]. The town grew in the 1890s with an influx of German-speaking Swiss immigrants, like those who founded the much smaller New Glarus [7]. In the middle of farming country, Monroe became a center of signature Wisconsin commerce. It had the Joseph Huber Brewing Company, founded as the Bissinger brewery around 1845. It’s the home of the Berghoff line and other tasty beers. In 1926 an enterprising UW graduate modernized the town’s cheese industry by creating the Swiss Colony [8], a mail-order firm that offered cheese, sausage, and baked goods. The Swiss Colony still employs several thousand Monroe citizens and now holds a considerable portfolio of other brands.

While many small towns are shrinking, Monroe has had a steady population of about 10,000 since 1980. It’s a very pretty place, with a well-preserved town square centering on a towering Romanesque county courthouse. Elsewhere are some well-wrought Victorian homes. The town’s Swiss heritage is preserved in several restaurants, social clubs like Turner Hall [9], and civic events, notably the Cheese Days [10] celebration.

Monroe had a succession of movie houses. Before 1920 there were the Nickelodeon, the Star, the Crystal, and the Lyric. Several of these were managed or owned by Leon Goetz, an early traveling film entrepreneur. He had run films in tent shows and town halls before settling in Monroe. In 1916 he opened the Monroe, the first movie house he built from scratch.

[11]Leon Goetz was a risk-loving man. To build a 500-seat film theatre in a town with about 4500 people reflects not only the growing popularity of movies but a conviction that the business had a future. In addition, the many farms and little towns around would supply customers; Monroe is the county seat of Green County, so people came here to transact business as well as to shop. Then as now, the nearest competitors to a Monroe theatre were over twenty miles away.

[11]Leon Goetz was a risk-loving man. To build a 500-seat film theatre in a town with about 4500 people reflects not only the growing popularity of movies but a conviction that the business had a future. In addition, the many farms and little towns around would supply customers; Monroe is the county seat of Green County, so people came here to transact business as well as to shop. Then as now, the nearest competitors to a Monroe theatre were over twenty miles away.

With his brother Chester as partner, Leon owned or managed other theatres in the area, including ones in Beloit and Janesville. The brothers’ biggest triumph, however, was building the Goetz Theatre. Opening on 2 September 1931, it was of semi-Moorish design, with faux balconies and moody cloud-and-star lighting on the ceiling. Light brown brick and darker brown terracotta inlays finished the outside. The lobby was forty feet high, with a gold finish and many trappings and fixtures.

Some unexpected innovations included seats equipped with earphones for the hard of hearing. The screen was 20 feet wide and fifteen feet tall. Accounts of the size range from 800 to 1000 seats. In all, the Goetz was said to have cost $125,000.

The Monroe had presented sound films using a system of Leon’s devising, but the Goetz was a step up, as the editors of the Monroe Evening Times indicated:

It should raise inestimably the respect with which talkies are looked upon locally and attract many persons who heretofore did not care to see pictures under the conditions in which they were shown.

The Goetz has run ever since. It’s said to be the oldest continuous family-operated movie house in the Midwest.

Leon retired to Florida but Chester stayed in the business, opening the Goetz Junior on Christmas day, 1936. It was “ultra modern,” as it advertised itself, with the Western Electric Mirrophonic [12] sound system and using streamlined design elements, like glass brick. Holding only 275 seats, it sometimes showed films not screened at the Goetz across the street, but other times it would screen the same films–sometimes on the same night, with reels rushed back and forth.

Soon Chester had competition from the Chalet, a 500-seat house around the corner. According to local memory, Chester cut ticket prices and then bought the floundering Chalet as a third Goetz house. Chester’s sons Robert and Nathan joined the business. Under Robert’s leadership, their company built the Sky-Vu Drive-in in 1954, and it too has been running without interruption every summer.

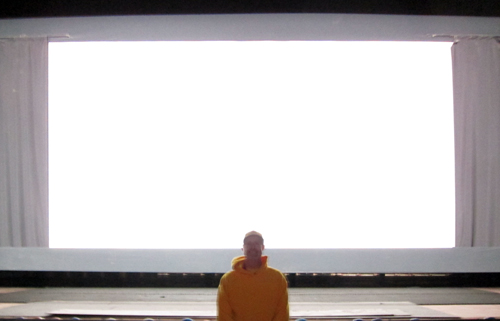

The postwar decline in movie attendance may have hit the family’s circuit. The Chalet and the Goetz Junior closed. In the 1980s and 1990s two screens were added at the Goetz, but unlike most old theatres that went multi-screen, the venue wasn’t split up. The new houses were converted from adjacent retail spaces. Visit the Goetz today and you’ll see the original auditorium. There are fewer seats, but it’s still enormous, as you can see from the front.

The third generation

Robert “Duke” Goetz. Behind him, counterclockwise, pictures of Conrad Goetz, Nathan as a child, Robert as a child, young Chester, and John. In the center, Chester Goetz.

For many years the downtown theatre and the Sky-Vu have been managed by Robert “Duke” Goetz, Robert’s son. He has a masters degree in landscape architecture from Harvard, but he’s been running the family business. He does everything from programming the movies and designing the website to wrench-and-hammer work on the place. He’s worked on heating, carpentry, and acoustic matters. Talk with him and you’ll hear about the tough times small-town exhibitors have faced over the last two decades. I learned as well some pressures on exhibition that I never thought about.

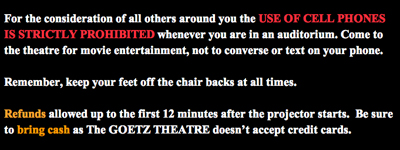

Duke Goetz has a commitment to showmanship and quality of presentation. The Goetz website has old-fashioned razzle-dazzle, including neon colors [15]. (Chester liked bright colors in his houses.) On another page [16] of the site you’ll see this:

Last Friday I saw Duke tell a gaggle of teenagers to shut off their cell phones, and he watched to make sure they did. The same pursuit of a good movie experience shows in Duke’s special attention to sound. Convinced that DTS is the best sound system for his venues, he has outfitted his smaller auditoriums with hard-hitting speaker systems. He installed tip-back seats, stadium seating in one house, and one belt-driven projector for steadier images.

Despite the commitment to quality, and programming that brings in family fare matched to local tastes, business has been rocky. Duke recalls some high points: 1993, when Jurassic Park did spectacularly at both the Goetz and the Sky-Vu; 1998, when Titanic brought in as many as a thousand viewers a night; and 2002, his best year in recent memory. That year was an exceptional spike for the industry as a whole, with estimated admissions of 1.57 billion, so just about anything less looks like a decline. Kristin talks about this effect here [18].

Duke’s business stayed flat but solid until 2007, when both the drive-in and the downtown screen began to slump. Business flattened out at a lower level through 2011. The only bright spot this year was Twilight: Breaking Dawn; the midnight premiere drew about 150 customers, mostly high-schoolers.

A good night at all three indoor screens is 300-350 tickets, but the Sky-Vu can reliably draw many more. Duke recalls one evening when the drive-in had over 1100 customers and sold 114 handmade pizzas. Today, even with competition from another local drive-in, the Sky-Vu’s summer schedule bolsters the bottom line significantly.

Why the falling off in recent times? I had expected the standard macro-explanations: the internet, video games, etc. But Duke’s main rival, he believes, is sports. In a town like Monroe, high school sports are central to community life, so Friday night football and basketball games draw not only teens but parents. With the rise of women’s athletics, the middle and high schools schedule plenty of games across the weekend. Add in the fact that televised football in the fall breaks up Saturday (the UW Badgers) and Sunday afternoons (the Packers), and you have a client base that isn’t focused so much on movies. Even the Christmas-New Year corridor, normally a brisk business period, is likely not to help much this time. The New Year starts on a weekend, so that the Packers’ final game on Sunday and the Badgers in the Rose Bowl on holiday Monday will compete with Duke’s screenings.

After three tough years, Duke looks at things realistically. He hires part-time staff to project, sell concessions, and keep an eye on the house, so he’s his only full-time employee. He adds: “I have not been paid since August 2010.” Digital, he admits, is chancy in this business climate. “But without digital, I’m gone.”

Duke goes digital

Duke Goetz saw his first digital screening around 2000 at a convention of the National Association of Theatre Owners (NATO) [20]. What attracted him was the edge-to-edge screen brightness. Judging by what I saw on Friday (from down front), the 1.85 image in 35mm at the Goetz is quite sharp, but Duke had long been unhappy with the inevitable falling-off of light toward the edges of any film display. The tendency is exaggerated in anamorphic (2.40) films, which have become more common. And the bigger the screen, the greater the tendency toward a hot spot in the center. In addition, Duke liked the punchier color in digital.

So he was intrigued. “I’d have loved to have done it ten years ago.” But then there was still debate about trustworthy delivery systems (the Net? satellite?) and the cost was astronomical, about $125,000 per projector. Last summer, though, it became clear that the digital wave was cresting, and time was running out for 35mm film. Also running out were the plans for the Virtual Print Fee, whereby the studios partially subsidize the cost of a theatre’s changeover.

This fall Duke took the plunge, arranging for three new NEC projectors from companies and installers he’s known for years. His final analog shows were last weekend. On Monday all houses were closed. By Tuesday night, the Goetz was running a digital copy of New Year’s Eve, which it had run in 35mm only a couple days before. By this coming weekend, all the digital screens are expected to be in action. Duke isn’t going with 3D, partly because he can’t justify the upcharge and partly because he’s not convinced it attracts enough extra business.

I was there for the Friday night 35 shows, and I re-visited on Tuesday. The whole changeover was less dramatic than I expected. In two of the houses, the old projectors were simply moved aside and the new ones sat stolidly in their place.

The gigantic platters were stacked in the hallway.

Reels, rewinds, and splicers sat in corners. All of the 35mm projectors were relatively new, but now one is now in the lobby as a historical artifact.

Duke thinks that digital will be even better for the Sky-Vu. The big screen is a problem for dimness and edge-to-edge brightness, but it should respond well to a digital beam. An indoor screen is porous to allow sound through, but that means that some light is lost. A drive-in screen is solid and should reflect light better. The brilliance of the digital illumination should also help counter chronic drive-in problems like fog, ambient light, moonlit nights, and some flaws on the screen.

The Goetz attendance flattening is part of a larger trend. The box office of 2011 has been weak, and for several years the total domestic admissions have hovered between 1.3 and 1.5 billion. Box office takings are up chiefly because of raised ticket prices, particularly for 3D and Imax. Professional predictors [25] are suggesting that this year’s ticket sales will end up about the same as last year’s.

It would be easy for us cinephiles to bemoan what happened between Sunday and Tuesday in Monroe, Wisconsin. We celebrate the look and feel of film, and we’d like to see old picture palaces become temples dedicated to 35mm. But we don’t pay the shipping and heating bills for those houses; we don’t dicker with bookers who won’t let us have prints when we need them. We like the idea of film surviving, but the practical people who actually deal with exhibition day by day can’t afford to satisfy our tastes.

And we purists would doubtless be scandalized at what film prints looked like when they made their way to the Goetz in the old days, six months or more after release. The Goetz Junior opened with Eddie Cantor’s Strike Me Pink nearly a year after it premiered in Manhattan. In April 1956 the Chalet was running a 1951 Roy Rogers movie. Take a time machine back to the 30s or 40s or 50s and you’ll probably watch a choppy, scratchy print. In comparison digital starts to look pretty good.

I’d like to see Duke succeed. Monroe’s theatre reminds me of the single screen of my childhood [26], Schine’s Elmwood in Penn Yan, New York. That theatre is long gone, so part of me hopes that somewhere a local movie house can still bring in the community–whether it’s showing film, 2K, Blu-ray, or vanilla DVD. When I was a boy, I wouldn’t have cared how those images got on the screen. In a town like Monroe, the theatre, and the neighborly spirit it represents, is as important as the emulsion. One item of evidence is my 1936 photo up top, taken from the Goetz website. Down past the Hollywood Inn, which I wish I could visit now, maybe you can make out the Goetz marquee: TODAY 2 BIG FEATURES IN GERMAN.

Duke closed out his 35mm shows on the worst weekend exhibitors had seen since fall 2008. Will digital bring Monroe area customers back? Once people realize that they will get high-quality presentation in their home town, perhaps they won’t drive half an hour to Freeport or an hour to Madison. But best not to prophesy. Duke realizes he’s taking the same sort of risk that Leon and Chester took when they built the Goetz at a price of what would be $1.7 million today. “My motto,” he says, “is go digital or die.”

This is the second in a series of entries on the conversion of filmmaking, distribution, and exhibition to digital formats.

Leon Goetz is also credited with producing at least two films, Ten Nights in a Bar Room [27] (1931) and The Call of the Rockies [28] (1931).

I thank Duke Goetz and Mrs. Robert Goetz for talking with me about the past and present of the family business. Other information comes from volumes of The Film Daily Yearbook and issues of The Monroe Evening Times of 1 September 1931; 23 December 1956; 22 October 1981; and 15 May 2001. Also very helpful was Pictorial History of Monroe, Wisconsin, ed. Matthew L. Figi (Green County Historical Society [29], 2006), supplemented by some discussion with Matt. Thanks also to the staff of the Monroe Public Library.

For better versions of the picture at the top of this entry and the frontal view further down, along with other high-quality images, go to the historical page [30] of the Goetz Theatres site. A chronology of the Goetz Theatres is on this page [16], and some shots inside the booths at the Goetz 2 and 3 are here [31].

P.S. 15 December: Thanks again to Matt Figli, who spotted some inaccuracies in my account of Monroe’s history. They have been corrected.

P.P.S. 28 December: Katjusa Cisar’s story in The Monroe Times [32] today brings us more information on the Goetz, both past and present.