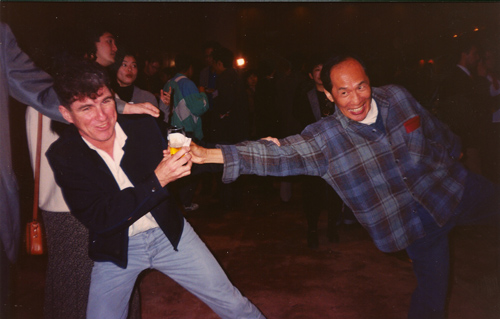

Your beer kung-fu is pretty good: Christopher Doyle and Po Chi Leung (Jumping Ash, He Lives by Night, etc.). Hong Kong Film Festival, 1996. Photo by DB.

DB here:

Planet Hong Kong, in a second edition, is now available as a pdf file. It can be ordered on this page [2], which gives more information about the new version and reprints the 2000 Preface. I take this opportunity to thank Meg Hamel, who edited and designed the book and put it online.

As a sort of celebration, for a short while I’ll run daily entries about Hong Kong cinema. These go beyond the book in dealing with things I didn’t have time or inclination to raise in the text. The first one, listing around 25 HK classics, is here [3]. The second, a quick overview of the decline of the industry, is here [4]. The third discusses principles of HK action cinema here [5]. A fourth, a portfolio of photos of Hong Kong stars, is here [6]. That was followed by a tribute to western Hong Kong fans [7]. The final entry [8] is concerned with the role of film festivals and a short list of other favorite films. Thanks to Kristin for stepping aside and postponing her entry on 3D.

When Andrew Sarris formulated an American version of the politique des auteurs, he used directorial “personality” as an index of true directorial creativity. Later, theorists and academics tried to define this elusive quality, and many concluded that auteur directors had recurring themes, a stylistic signature, and what we might call storytelling manner. To sketch an example: Welles can be thought of as concerned with the relation of power to love, and the loss of both. He favored aggressive depth compositions, long takes, and unusual uses of sound. In narrative terms, he was fond of stories featuring a larger-than-life man, turning on a puzzle or a crime, and presented in some time-shifting ways (e.g., flashbacks). This is a unsubtle characterization, but my point is simply that crtiics thought that recurring qualities like these offered a strong case for directorial authorship.

Yet a mass-market cinema makes “pure” authorship difficult, since directors may not freely choose their projects and their artistic preferences may be overridden by budgets, weather, producer rulings, censorship and the like. Creativity in a film industry, we’re usually told, requires collaboration. That’s true, but of course many other art forms do as well, notably theatre, dance, and song composition. A director may not explore favorite thematic concerns every time out (Look: stick to the script!), or may be thwarted in certain technical choices (We can’t afford long tracking shots!) or storytelling strategies (We’re adding a voice-over to clarify the backstory).

As with most high-output cinemas, the appeal of many Hong Kong films can be traced not to directorial flair but to the genre and other components (stars, scripts, studio resources). I wouldn’t say that many of the Jackie Chan-Sammo Hung-Yuen Biao outings like Winners and Sinners (1983), Wheels on Meals (this is not a typo; 1984), and My Lucky Stars (1985) exhibit much directorial personality, but they are skillfully made and pretty entertaining. Every industry needs its artisans, its steady hands on the tiller; it’s no mean feat to turn out a solid movie. Even the most distinctive directors in an industry need craft competence; as Sarris once remarked, “A great director has to be a good director.” Much of Planet Hong Kong is about the collective norms of local filmmaking, the tricks of the trade and the professional practices that shape the artistry of non-auteur movies.

But are there true Hong Kong auteurs? I think so, to various degrees. Ones discussed in PHK 2.0 are King Hu, Chang Cheh, Lau Kar-leung, Tsui Hark, Wong Kar-wai, and Johnnie To Kei-fung. John Woo, I argue, is one in a special, almost meta-sense: He understood the idea of authorship and crafted his public image, as well as his films, around certain themes (Christianity, heroic self-sacrifice) and stylistic choices (most visibly, flying pistoleros).

Wong Jing is a bit meta- too, in the way that Mel Brooks is a parodic auteur. Wong Jing’s farcical cinema carries to an extreme the vulgar potential always lurking in his territory’s cinema. He can provide quite precise mockery of other (better) directors, as when the arthouse filmmaker in Whatever You Want (1994) turns out a pretentious effort suspiciously similar to Ashes of Time. The evocative, fragmentary shots of Carina Lau Ka-ling clutching at her horse are replaced by one of Law Kar-ying caressing a cow.

So it was in hope of learning both about craft norms and directorial temperament that between 1995 and the present I’ve visited and talked with various filmmakers. The results are in the book, but here are some photos commemorating the encounters.

Here Ann Hui On-wah presents Wong Kar-wai with the best screenplay award (for Ashes of Time) at the first annual Hong Kong Film Critics Society [12] Awards, 1995. She looks as happy as he is. The film also won Best Film, Best Director, and Best Actor (for Leslie Cheung Kwok-wing, who wasn’t present). For a further note on Wong, check the bottom of this entry.

My longest stay in Hong Kong was during the spring of 1997. Doing research for PHK, I interviewed several people. One of my top stops was BoB & Partners, then the latest incarnation of Wong Jing’s entrepreneurship. (On the wall in the left still you see posters for Naked Killer, 1992, and other genre classics.) BoB stood for “Best of the Best,” and one of the partners was Andrew Lau Wai-keung, top-flight cinematographer who had become famous as a director with the Young and Dangerous series. Soon he was to go on to Storm Riders (1998) and eventually to the Infernal Affairs trilogy (2002-2003). Next door, Wong Jing also talked with me. He had several TV screens facing him, one with video games, and you can see his console front and center on his desk.

Another busy man, Peter Chan Ho-sun, had become an important director of contemporary comedies and dramas (e.g., He’s a Woman, She’s a Man, 1994; Comrades, Almost a Love Story, 1996). I met him in 1997 and brought him to Madison in 1999; below, a photo from 2008. Even more prolific, and less easy to categorize, is Herman Yau Lai-to–DP, rock-and-roller, and director of everything from grossout horror (The Ebola Syndrome, 1996) to harsh social critique (From the Queen to the Chief Executive, 2001; Whispers and Moans, 2007). How could you not learn a lot about filmmaking craft from a guy who had directed over fifty movies and been DP on thirty-five more? I wrote about Herman’s On the Edge here [15].

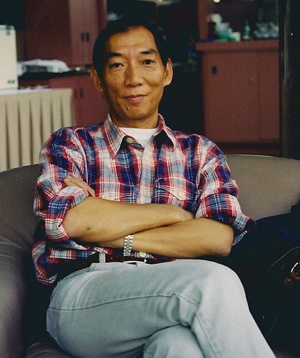

I met some directors from the older generation too. There was Yuen Woo-ping (aka Yuen Wo-ping), one of the great fight choreographers (The Matrix, Kill Bill) but also a lively director in exhilarating films like Legend of a Fighter (1982), Dance of the Drunk Mantis (1979), Iron Monkey (1993), and Tai-chi Master (1993). And there was Ng See-yuen, another local legend. He directed some sturdy kung-fu films like The Secret Rivals (1976) and The Invincible Armour (1977). He’s also an iconoclastic producer, backing Jackie Chan’s breakthrough film Snake in the Eagle’s Shadow (directed by Yuen Woo-ping), Tsui Hark’s Butterfly Murders (1979) and We’re Going to Eat You (1980), and several of the Once Upon a Time in China entries. Here Ng is at the 1997 Hong Kong Film Awards.

Two of the high points were my interviews with major figures of the Hong Kong New Wave of the 1980s, both still going strong in 1997. Ann Hui was warm and generous with her time; she visited Madison that year with Summer Snow (1995) and other films. The picture below is from 2005.

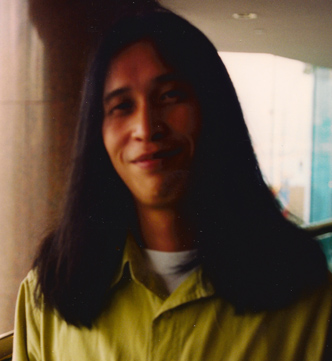

Then there was my several-hour talk with Tsui Hark at the Film Workshop headquarters. Good thing I taped it; I couldn’t keep up with him in my note-taking. He was planning Knock-Off and the animated version of Chinese Ghost Story.

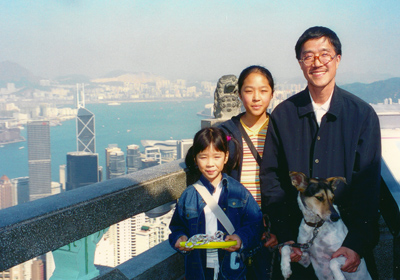

After 1997, I looked in on some other filmmakers. I was invited to visit the Academy for the Performing Arts in 2001 under the guidance of Professor Lau Shing-hon, another early New Waver (House of the Lute, 1980; The Final Night of the Royal Hong Kong Police, 2002). Here he is with his family on the Peak.

Since I started blogging, I have put my best (or rather the least amateurish) shots online. So for more snaps, you can rummage through the category, Festivals: Hong Kong [23]. But I can’t resist two final ones. Here are Johnnie To and the younger director Soi Cheang Pou-soi (Love Battlefield, 2004; Dog Bite Dog, 2006; Accident, 2009), in shots from 2005 and 2009 respectively.

And now for something not quite completely different. In both print and e-book editions of Planet Hong Kong, I wrote about our last view of the Brigitte Lin Ching-hsia’s character in Chungking Express. Wong Kar-wai presents a jerky slow-motion shot of her leaving the crime scene and dodging out of the frame. It freezes on her, at a moment that yields a perversely unreadable image.

A shot of this frame would have been mud in the black-and-white pages of the book and probably not much better in the color pdf. I couldn’t imagine catching the faint reddish glint of the woman’s sunglasses. (Actually, the e-book’s quality turned out well enough that we might have tried for it.) So I picked the most legible image I could find from the shot, and that’s what’s in the print book and the digital copy (Fig. 9.13).

In any case, for obsessives like me, I reproduce the frozen frame here. This still comes from a 35mm print of the movie, and it is, of course, a lot more poetic than my snapshots, partly because it teases you about what’s in the frame.