A Touch of Zen (King Hu, 1970).

DB here:

….really is a jump cut.

I had spent a day studying King Hu’s The Valiant Ones at an archive. That night over dinner, my friend asked me what was taking me so long. I answered, “I’m trying to figure out his secrets.” Her brow furrowed, but then she said, “I suppose that’s all right as long as you never tell anyone.”

Reader, I told. Eventually.

The puzzle for me was how King Hu gets the remarkable kinetic effects in his fight scenes. He starts with the conventions of the Chinese wuxia (“martial chivalry”) film. Fighting with or without weapons, the warriors have extraordinary powers of speed and strength. They can sometimes defy gravity with “weightless leaps” that carry them great distances.

Today, digital special effects permit quite dazzling images showing flying warriors in extended long shots, as in Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon and Hero. But Hong Kong directors of the 1960s and 1970s had much more meager special effects available.

The alternative was to present these feats through constructive editing [3]. A character leaps in shot A, flies through the air in shot B, and lands in shot C. All much easier to film than a single, faked long shot. From the 1980s on, strong but thin wires would keep the fighters in the air for long shots. Many fine films were made using wirework, but for the most part King Hu couldn’t use it. About his only technological support was a variety of trampolines that could be cunningly hidden in a set.

King Hu’s solution to the problem of flying swordfighters involves a unique approach to film technique. In an article called “Richness through Imperfection: King Hu and the Glimpse,” I argued that he found a way to make his fighters’ prodigious moves register in a percussive but almost subliminal way. It’s not just that if you blink, you miss the action. (Though if you do, you will.) His goal isn’t just to use brief shots (some only three or four frames long) to arrest our attention. More important, King Hu evokes the quasi-supernatural power of his fighters by suggesting that they move too quickly and unpredictably for the camera to catch.

He accomplishes this by reshaping the constructive-editing scheme of launch/leap/landing. He trims each shot to a minimum, provides several intermediate flying shots (each also very short), and makes our eye work by shifting the center of interest from shot to shot. He provides eccentric angles, unexpected cuts, and startlingly empty frames. Characters run, spring up, and soar, but in a flurry of frames, or on the screen edge, or dodging in and out of sight–blocked by bits of the set, or just by a framing that doesn’t adjust quickly enough to their impulsive movements.

A good example is the moment in Dragon Gate Inn (1967) when the eunuch Tsao attacks the group defending the family of General Yu on the roadway. A low angle shows him launching his jump.

So far, so conventional. But instead of giving us a clear image of Tsao in flight mode, Hu gives us this:

Tsao slides down the left frame edge, vanishes for an instant, then bounces up, already somersaulting, on his way to strike his adversary Hsiao. The framing fails to keep up with him, implying that he’s just too elusive, while his wayward entries into the frame provide percussive accents.

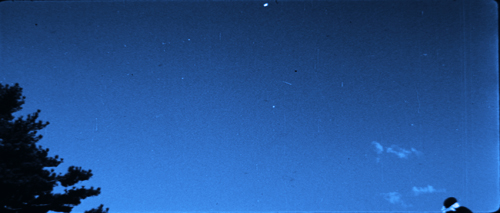

King Hu liked to play with the leap phase of the ABC pattern, as here and in my knockout passage for the day, shown at the top of the entry. In the penultimate confrontation of A Touch of Zen, Commander Hsu attacks the serene Abbot Hui Yan. Hsu leaps a huge distance and comes down directly in front of the monk. But King Hu renders this miraculous feat in two nearly identical framings: one showing the launch, the other the landing. Seen from over the monk’s shoulder, Hsu has been endowed with blinding speed through a sheerly cinematic effect–a bold jump cut.

Please note: This isn’t a clumsy patch job in the particular print. The cut is in the negative, and it’s been in every print I’ve ever seen of Touch of Zen.

“Jump cut” is a term that’s used in different ways. Sometimes it refers to various kinds of mismatches that yield a jolting discontinuity. I’m using the term here to denote an effect that results from excising some frames from a continuous shot. The classic examples have always been the cuts in Godard’s Breathless. The Touch of Zen example is a little less pure because you can see that Shot 2 doesn’t strictly continue Shot 1’s camera setup. King Hu has moved the abbot’s head and shoulder a little further away from us. But the compositions are graphically very close, and the impression on screen is of a single camera take with some frames lopped out.

When we ask, Where did Hsu go from shot to shot?, the answer is: In the cut. Without the advantage of special effects, King Hu has given us a propulsive impression of speed and ferocity.

His secret? Merely a uniquely cinematic imagination.

Some of our techie readers might be curious about the images here, photographed from a 35mm print. Perhaps they’ve noticed that Hu’s cutting has left its physical trace on the film strip.

In classic filmmaking practice, cuts were made with splices–physical joins between one piece of film and another. In film-based formats, splices were made with glue or transparent tape. (Today, of course, they’re largely made digitally and called “edits.”) Most filmmakers hid their splices, but there’s a robust tradition in avant-garde cinema of integrating splices into the image; you can see it, for example, in the work of Stan Brakhage [8] and Paolo Gioli [9].

Splices are visible as horizontal flashes across the bottom of the screen. In 35mm filmmaking, the final printing phase usually masks those out. But, as Erik Gunneson reminds me, that’s harder when you’re shooting anamorphic scope. There the image is recorded full-frame on the film strip, so traces of the splice may remain visible, especially in older films.

When we look at the physical strip here,we can see that Hu’s negative cutter has simply spliced one shot to another with cement. The illustrations up top show the last frame of Shot A and the first frame of Shot B. You can see the neat splice, a horizontal line running along the bottom of the first frame and the top of the second. The same trace of a splice is visible in the cut involving Yang’s leap.

The odd thing to modern eyes is that there’s a bit of overlap, a thin slice that seems out of whack with both shots. In Shot A, the bottom edge of this thin strip cuts off the abbot’s head weirdly. Let me show you the first frame of the second shot again. Reading from top to bottom, you see a bit of the bottom of Shot A’s last frame, then the true frame line, then the weird little band. The bulk of the image is the frame that starts Shot B.

What’s that thin slice between the frame line and the yellow splice line? It’s the top bit of the next frame of the first shot as taken in camera. It shows the trees and the abbot’s head and ears as they appear at the top of Shot A’s composition. Instead of cutting exactly on the frame line of Shot A, the editor has overlapped a tad of the following frame in order to attach the two shots with cement. During a screening, the extra bit may be minimized or eliminated because the projector plate doesn’t show us the entirety of the image on the strip, but it is there.

Splices can be hidden through A/B rolling [11], which I believe is more common in 16mm than in 35mm production. I don’t believe that Chinese films of Hu’s day made use of this process, but I’d appreciate more information.

The essay on King Hu is in my Poetics of Cinema (Routledge, 2008), 413-430. For more on King Hu and his innovations, see Planet Hong Kong: Popular Cinema and the Art of Entertainment, available elsewhere on this site. Kristin and I discuss jump cuts and graphic matches in Chapter 6 of Film Art: An Introduction. See also the “Film Technique: Editing” category on the right of this page.

This blog entry follows from two others: “Sometimes a shot . . .” [12] and “Sometimes two shots . . .” [13]

I put up this post now because I’ll be giving a talk on Chinese martial arts cinema [14] next Monday, 10 June at the Toronto International Film Festival Bell Lightbox, at 6:30. It’s a part of TIFF’s splendid summer-long celebration of Chinese cinema [15]. On the day before, 9 June, there will be a free screening of Hou Hsiao-Hsien’s Dust in the Wind [16] (1987) at 10:00 AM. After the show, there’ll be a panel [17] featuring Bart Testa, Hou expert Jim Udden [18] (who posted a blog entry with us [19] on Hou’s new project), and me.

This entry is also to congratulate Peter Rist [20], tireless guardian of the Shaolin Temple, on his birthday.

A Touch of Zen.