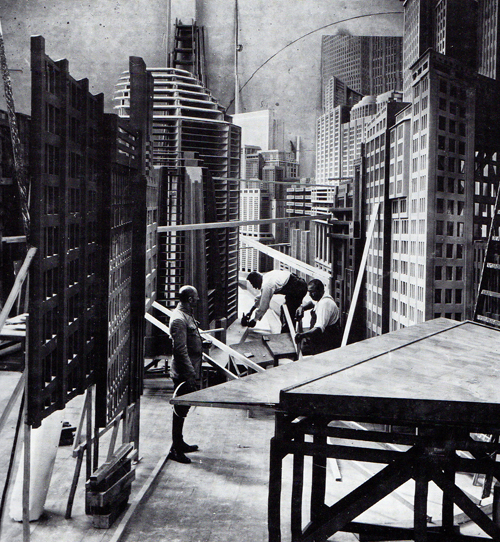

Shooting Frau im Mond (1929) at Neubabelsberg studio, Potsdam.

DB here:

Friends say that Berlin is now the most exciting city in Europe–a little too exciting [2], others say. I can’t prove either claim, but I can declare that I had a fine time last month during my second visit [3] to Germany this year. Part of the fun was, as usual on many of our trips, finding tangible traces of film history.

Stylin’

Lobby space, Konrad Wolf Film School.

With Michael Wedel, I re-saw Hong Sang-soo film’s Turning Gate in the wonderful Arsenal theatre [5], part of the Deutsche Kinemathek [6]. The Arsenal is run by Milena Gregor, another old friend (who happens to be Michael’s wife). On another night I also had a delicious dinner with filmmaker Christine Noll Brinckman and other friends. Then there was a pleasant lunch with another filmmaker, Carlos Bustamante (below), in his picturesque neighborhood.

But Berlin literally wasn’t the half of it. I visited Philipps Universität in Marburg [8], a charming university town. Part of the campus fronts onto the Lahn River, and it makes a charming place to relax.

After my lecture on 1940s Hollywood, my hosts Malte Hagener and Dietmar Kammerer took me out to dinner with their lively colleagues.

Most of my visit was spent in Potsdam, where I’d been invited by the Netzwerk Filmstil [10]. This is a research team composed of several young professors teaching in German-language universities around Europe. Their focus is the exploration of style in audiovisual media–centrally film, but not ignoring television, video games, Internet pieces, and even surveillance and security videos. The two and a half days of the seminar were very stimulating. Michael Wedel, Chris Wahl, Malte, Dietmar, and Kristina Kohler gave illuminating papers on (respectively) digital sound, superimpositions, split screen, freeze-frames, and dance in silent film. The participants offered me good criticisms of my presentation, which explored how E. H. Gombrich’s explanations for stylistic change in visual art might apply (or not) to cinema.

Our seminar sessions were held in the remarkable Konrad Wolf Film School [11], a towering building crisscrossed by staircases and walkways. I visited it once before some years ago, and once more I admired its airy yet rectilinear architecture.

The stripped-metal look is offset by lots of glass–the light pours in from all directions–and a corner with plenty of plant life. As in our house back home, winged silhouettes on the windows keep bird-brains from flying into the glass.

I also gave a talk on film style during the 1910s at the monumental Filmmuseum Potsdam [14].

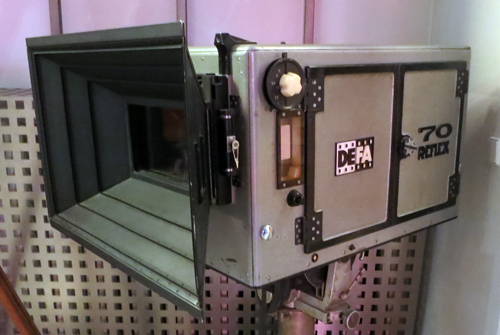

The museum holds a fine screening space and a fascinating collection of historic materials, including a Soviet-era 70mm camera.

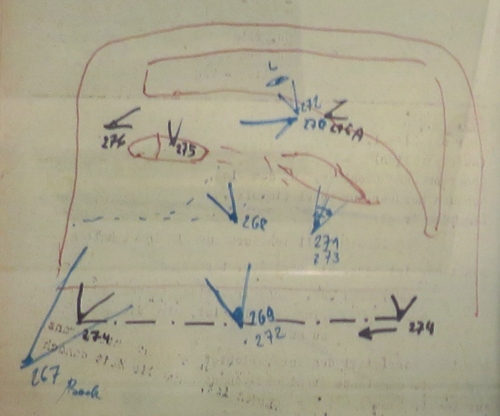

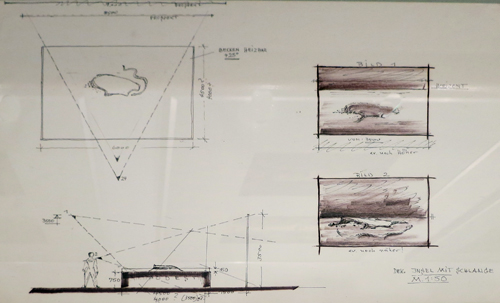

The current exhibition [17] was devoted to the rise of the film studio Babelsberg, not far away. The displays included scripts, set photos, production sketches, photos, and maquettes.

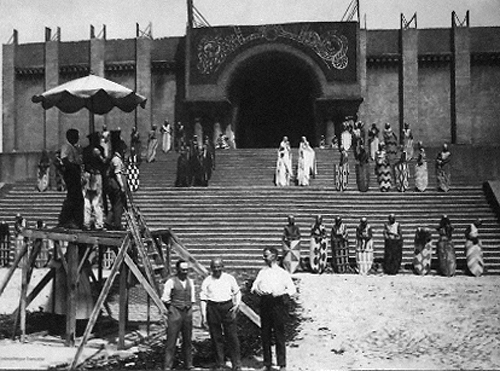

Have you seen this still of the great Cathedral set from the Nibelungen?

The tradition of fastidious planning created during the silent era persisted into the period of the German Democratic Republic. Each set design was marked up to show camera positions (numbered), lens lengths, and special-effects elements.

The Filmmuseum’s collection was only one reminder of the towering importance of Babelsberg, now celebrating its hundredth anniversary year. Luckily the studio was an easy walk from the Konrad Wolf school. One sunny day our host Michael Wedel took the Style Network on an insider’s tour.

Babelsberg’s birthday

The 1910s and 1920s saw many production facilities spring up in Germany. Films were made in Munich, Frankfurt, and other major cities, and the area around Berlin boasted a number of studios. But the Potsdam facility, initially called Neubabelsberg, became the most well-known, something like Europe’s answer to Hollywood.

Founded by the Deutsche Bioscop company, the studio began production in 1911 and released its first film, Totentanz (The Dance to Death), in 1912. That starred Asta Nielsen, whose popularity had already enriched Bioscop. In this story she’s attracted to a rather louche composer, as we see below. (Yes, that mass of black is mostly her hat.) Later, she slices the guitar strings in a fit of passion and glares out defiantly at us. As if our attention might wander.

Neubabelsberg was home to such classics as The Student of Prague (1913), the Homunculus series (1916-1917), Madame Dubarry (1919), The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920), The Golem (1920), and Genuine (1920). Fairly soon Bioscop merged with Erich Pommer’s Decla, and in 1921 the big company Ufa took over the facility and the resident firms. Ufa also had a studio in Tempelhof, a Berlin suburb, but the attention-grabber was Neubabelsberg, which became a sprawling complex of 350,000 square meters–the biggest studio in Europe.

Here Murnau shot Phantom (1922), as well as portions of The Last Laugh (1924). E. A. Dupont filmed some of Variety (1925) here, and Pabst shot all of The Loves of Jeanne Ney (1927) on its stages. Above all, Neubabelsberg helped sustain one of cinema’s great hot hands, the string of films Fritz Lang made in the 1920s: Destiny (1921), the Mabuse duo (19221-22), the Nibelungen saga (1924), Metropolis (1927), Spies (1928), and Woman in the Moon (1929).

The studio remained a powerful force across the next two decades, from The Blue Angel (1930) to the epic color production The Adventures of Baron Munchausen (1943).

The partitioning of Germany after World War II put it the studio the eastern sector, and the new state-sponsored film company, DEFA (Deutsche-Film-A. G.), took over the facility in 1953. That made it what Ralf Schenk calls “the exlusive site of feature cinema production in the GDR until 1990.”

After the Wall came down, the Babelsberg studio revived itself as a facility for international productions. It has hosted films by Polanski (The Pianist, The Ghost Writer) and Tarantino (Inglourious Basterds; below, a set on the Babelsberg backlot). The Wachowskis have been loyal supporters, with Speed Racer, V for Vendetta, and most recently Cloud Atlas using the facility.

You can get a sense of the studio today by visiting the website [28], which presents it as a modern resource for world filmmaking. But its early years matter more to me. To walk these quiet pavements and to imagine following in the steps of Lang, Jannings, Dietrich, and other legends ought to thrill any cinephile. Seeing some streets named for the greats, Tarantino requested a street in his name. It’s apparently a dead end.

A new Babylon

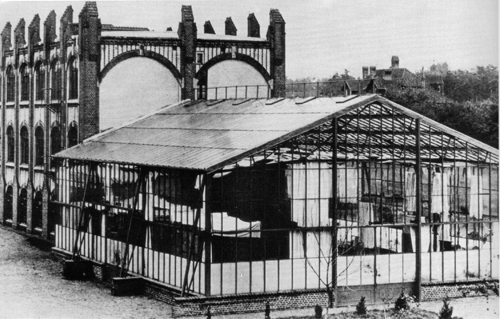

In the cold winter of 1911-1912, Deutsche Bioscop built its first studio, a 45 x 60 foot “glass house”at Babelsberg.

Michael Wedel explains:

Not only was a special cement-less glazing developed for the glass, but even the supporting beams of the infrastructure had to be installed outside of the studio, so as not to spoil the sunlight. . . . In contrast to already existing glasshouse studios that had been “set up” in Berlin and Munich in multi-level apartment blocks and office buildings, the ground-level location of the new Bioscop building at Babelsberg had the advantage of trucks with props and sets being able to be driven through a sliding door directly into the glass studio. . . .

Michael again:

The ground floor of the immediately adjacent factory building accommodated wardrobe and prop rooms, a woodshop, art studio, and a canteen. On the first floor, the production company’s office, as well as the laboratory for developing negatives and positives, were set up. On the floor above was where one found the dry drums for developed film material, the room in which the films were edited, and the rooms where intertitles were prepared. Except for the costume department, which would be built systematically a few years later, Bioscop oversaw a completely integrated film studio, which made it possible to perform most stages of film production on-site.

Later in the 1910s Guido Seeber, the cinematographer and all-around creative genius who had planned the Babelsberg plant, began to use supplemental artificial light. But this glass house and its bigger brother, built later, were relied upon throughout the silent era. A closed unit lit entirely by artificial light wasn’t built until 1926. Appropriately huge, it was called the Great Hall and eventually renamed the Marlene Dietrich Stage.

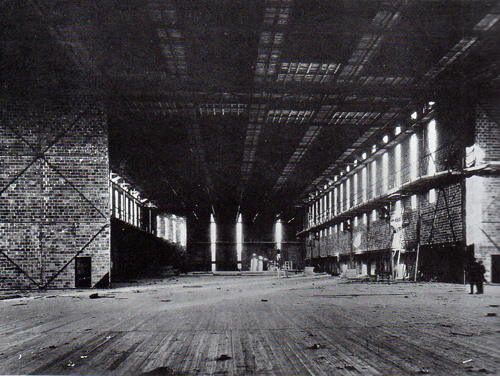

The Frau im Mond production shot atop today’s entry was taken in the Great Hall. Here’s another picture of the interior in the late 1920s. In both shots, those little figures on the far right are men.

On our stroll we caught glimpses of some filming taking place in a parking lot.

Not quite as glamorous as the behind-the-scenes action on–oh, let’s say Metropolis.

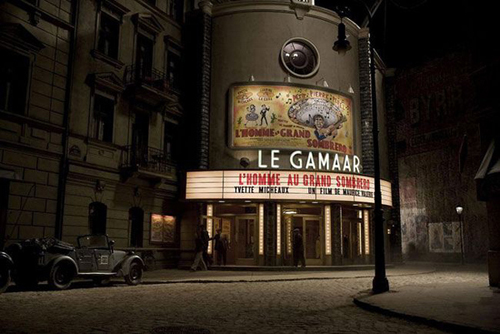

We ended our unofficial tour with a quick look at the backlot, which can be redressed to be almost any European city you like.

Movie magic, the Dream Factory: the rationalist side of me rejects these catchphrases as mere mystification. Filmmaking is hard thinking and hard work. But it’s tough to be purely rationalist when you’re facing an illusion machine that has thrilled audiences worldwide for a hundred years. If you see Hansel & Gretel: Witch Hunters, spare a thought for the tradition of Germanic lore that made it possible–and the hard work of the thousands of men and women who built a cinematic metropolis here.

Thanks to all my hosts and colleagues for making my trip to Germany, however short, intense and enjoyable.

Noll Brinckmann’s films and writings are available, at least in part, in this edition [37]. A sample of Carlos Bustamante’s recent work is available online here [38].

For a fairly detailed timeline of Babelsberg’s history, see this page [39] of the Filmmuseum site. When spring comes, you can take a studio tour (German language only) or visit the nearby theme park [40].

My quotations come from Michael Wedel, ChrisWahl, and Ralf Schenk, 100 Years Studio Babelsberg: The Art of Filmmaking (teNeues, 2012). This is that rare coffee-table book whose historical texts (footnotes included) are as valuable as the luxurious photos. The book, in an English/German edition, is available from the Filmmuseum [41] and from Amazon.de [42].

This post gathers information from Hans-Michael Bock and Michael Töteberg’s encyclopedic Das Ufa-Buch [43] (Zweitausendeins, 1992). Also helpful was Klaus Kreimeier’s The Ufa Story: A History of Germany’s Greatest Film Company, 1918-1945 [44](Hill and Wang, 1996).

We hadn’t planned it this way, but Kristin’s previous entry [45] discusses several recent DVD releases of German classics. I wrote a little bit about Totentanz (1912) here [46].

My lecture at Potsdam, “How Motion Pictures Became the Movies,” was a new version of a talk I’ve been giving for the last couple years to whatever audiences of innocents that fate has flung my way. Alert filmmaker Erik Gunneson, who prepared our video essay on constructive editing [47], is currently turning this talk into a video lecture. We hope to put it up on this site early in 2013.

The stylish Film Style Mafia, Neubabelsberg, November 2012.

10 Dec 2012: Thanks to Antti Alanen [49] for two spelling corrections!