The entrance to the Brussels Cinematek screening rooms. No cellphones, no drinks, and above all no frites.

DB here:

As every year, I’m spending time in Brussels doing research at the Royal Film Archive, and as usual every two years, I’m preparing to go to the Flemish Film Foundation’s Summer Film College, this time in Antwerp. My stay was timed, also as usual, to the Cinédécouvertes festival [2] sponsored by the Cinematek.

Cinédécouvertes is a partly a festival of festivals, gathering most of its titles from Venice, Rotterdam, Berlin, and Cannes. It’s a good way for me to catch up with several top-flight films unlikely to come to the US, or at least any time soon. (See the links at the bottom of this entry for my earlier observations.) In screening only films that have not been bought for Belgian distribution, Cinédécouvertes’ record shows a keen talent-spotter’s eye. Just in the last ten years, its winners have included Japón, Oasis, Shara, Tropical Malady, Day Night Day Night, How I Ended This Summer, and Police, Adjective. The year 2000 was remarkable, with prizes given to four films: Miike’s Audition, Im’s Chunhyang, Kurosawa’s Barren Illusion, and Tarr’s Werckmeister Harmonies. My affection for this modest but robust festival goes back to the 1980s; it introduced me to films by Hou, Kitano, and Kiarostami when they were genuine cine-discoveries.

This year Bruno Dumont’s Hors Satan took the L’Age d’or prize, the one reserved for films that seek to disturb us in the vein of Buñuel’s classic. That prize consists of 5000 euros given to the filmmaker. The two other awards aim to support local distribution of the best work. The Austrian entry Atmen (Breathing) by Karl Markovics and Alejandro Landes’ Porfirio, set in Colombia, won the prizes. If either is picked up for Belgian release, the distributor will receive 10,000 euros to help cover costs. Shouldn’t other festivals imitate this strategy for getting films onto screens?

My lecture preparations for Antwerp kept me away from many festival offerings, but I did see two of the prizewinners. Atmen and Hors Satan reminded me that a lot of European art films, despite their reputation for being slow, have a crisp, laconic style. Abrupt cuts open and end scenes, while an unexpected close-up can accentuate a moment. This sort of precision meshes with other conventions of this tradition: delayed exposition, long scenes without dialogue or music, routines that structure the plot, and a demand that we let things unfold at a rhythm different from that of the goal-driven Hollywood cinema. Early on, the scruffy idler of Hors Satan shoots down a man while the vaguely punkish girl with him doesn’t bat an eye. What registers is the bare, brute act, no more and no less.

Eventually we’ll learn some causes and reasons, but in this mode of cinema, a gesture is given heft by coming out of nowhere, without benefit of much preparation. What we can count on is the repetition of a routine, such as the man’s praying or his receiving a piece of bread each day from an (initially) unseen donor. Sooner or later, something will emerge–a pattern of activity, if not a straightforward plot.

Similarly, we know almost nothing about the young man who gets dressed at the start of Atmen. Only gradually will his routines reveal his work-release from a juvenile prison and his growing awareness of his responsibility for the crime that put him there. In this unvarnished tale, which sends young Vogler to work assisting a mortician, we get nothing like the mixture of humor and poignancy we find in Takita’s Departures. Everything here is cool, even curt, with each shot providing a bit of action that we have to fit into the personality lurking behind Vogler’s guardedly blank expression.

That personality becomes clear, in a rather conventional way, when Vogler sets out to find the mother who abandoned him. Things are much more opaque in Hors Satan, in which miracles and near-miracles are performed with a grimy physicality suited to provincial life lived among marshes and rocky hillsides. If Atmen pulls into focus as a fairly clear-cut psychological drama, Dumont’s film tries for something grander and less committed to personality. It seems to me to aim for a sense of flinty, rough-hewn holiness that is beyond conventional piety. In The Tree of Life, faith bathes the lovely faithful in a glow–hell, it can make them levitate–but here faith, if that’s what’s involved, is irredeemably coarse, even ugly. (Hors Satan reminded Cinédécouvertes judge Charles Tatum of Abel Ferrara.) Like Atmen, though, Hors Satan gets to its destination through a storytelling technique that we can trace back to neorealism and its respect for dawdling exposition and the undramatic singular detail. Some cinematic traditions are endlessly fertile.

Earnest Goes to Summer Movie Camp

The Last of the Mohicans [6] (1920).

This year’s July film college [7] is woven of three strands. One is called “Masterpieces in Context,” and it includes films by De Sica, Ford, Flaherty, and others. The primary strand is devoted to film and the visual arts, and given my interests it looks exciting. Steven Jacobs will present lectures related to his new book, Framing Pictures [8], to be published during our event. Steven will survey a range of relationships between cinema and painting, including films about artists (e.g., Caravaggio) and scenes set in museums. Wouter Hessels, the incoming Director of the Cinematek, will discuss work by André Delvaux and other Belgian filmmakers. Lisa Colpaert will talk on “Noir Portraits.” And Tom Paulus will survey instances of the influence of painting and photography on directors’ visual style, ranging from Tourneur to Tarkovsky. Films include The Last of the Mohicans (1920), Spirit of the Beehive (1973), and Arsenal (1929). I’ll throw in my $.02 with a lecture called “Seeking and Seeing: Lessons from E. H. Gombrich,” which hopes to show how Gombrich’s approach to art history can help us study film history.

My main contribution, though, is to a third strand called “Dark Passages: Storytelling in 1940s Hollywood.” Through screenings of Suspicion (1941), Daisy Kenyon (1947), Laura (1944), A Letter to Three Wives (1948), and six other movies, I’ll survey some narrative innovations of this remarkable era. Our main attractions are A pictures, but I’ve pulled some clips and stills from B’s, which are no less intriguing in their flashbacks, dreams, hallucinations, splits in point-of-view, and treatments of mystery and suspense.

I’m still working on the talks, but what’s emerging is one unorthodox premise. As an experiment in counterfactual history, let’s pretend that World War II hadn’t happened. Would the storytelling choices (as opposed to the subjects, themes, and iconography) be that much different?In other words, if Pearl Harbor hadn’t been attacked, would we not have Double Indemnity (1944) or The Strange Affair of Uncle Harry (1945)? Only after playing with this outrageous possibility do I find that, as often happens, Sarris got there first: “The most interesting films of the forties were completely unrelated to the War and the Peace that followed.” Sheer overstatement, but back-pedal a little, and I think you find something intriguing.

Some lectures are in English, some in Dutch. All screenings are 35mm, with live accompaniment for the silent films. There will also be an excursion to Antwerp’s gorgeous, widely praised [9] new museum, the MAS [10]. It’s open until 11 on weeknights and until midnight on weekends, an admirable idea. I’ll be sure to take photos of the skull-mosaic terrace.

More on the summer film school after I’ve done it. In the meantime, coming up blog-wise: ideas about how people might have watched movies a hundred or so years ago.

I first explained my research in the film archive here [11]. For previous years’ notes on the Cinematek’s annual festival, you can go to the category here [12]. On the Cinephile Summer Camp, here is the report on the 2007 gathering [13] and here’s the one on 2009 [14]. Sarris’ scandalous claim (yes, I too thought about The Best Years of Our Lives, They Were Expendable, Ministry of Fear, etc. etc.) is in the introductory essay, “Toward a Theory of Film History,” in his classic book The American Cinema (New York: Dutton, 1968), 25.

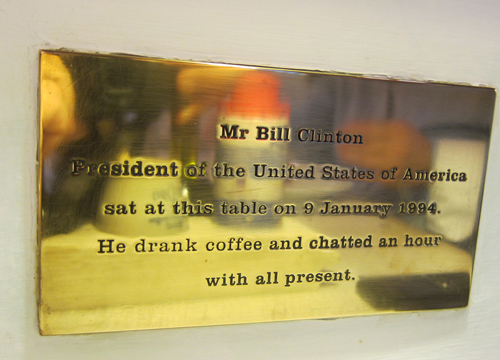

I especially believe the “with all present” part. This is apparently the table to get at Au Vieux St. Martin [16], Brussels. In reflection is Nicola Mazzanti of the Royal Film Archive.