Filibus: The Mysterious Air Pirate (1915).

DB here:

Two new DVD releases remind us how 1910s filmmakers, unconstrained by realism, used the newish medium of film as a vehicle of charming, sometimes silly fantasy. One is the virtually unknown 1915 Italian feature Filibus: The Mysterious Air Pirate [2]; the other is the famous but little-seen 1919 serial adventure Tih-Minh, by Louis Feuillade. The Filibus disc also contains a 1916 Italian feature Signori giurati… (“Gentlemen of the Jury,” here The Jury Decided). None seems to me a masterwork, but all are enjoyable and have something to teach us about the almost mad ambitions of an era discovering the power of long-form cinematic storytelling.

Lady with an airship

One thread over the life of this blog has been my nagging claim that the 1910s have not been widely recognized as the lively, innovative years they were. Yes, there was Griffith and Chaplin, but after that people tend to move on to rhapsodize about the glories of 1920s Europe and Hollywood. Of course many viewers appreciate the early work of Mary Pickford, William S. Hart, Buster Keaton, and Doug Fairbanks, and there are fans of great European directors like Sjöström and Feuillade, but even these luminaries are chiefly known for only a film or two.

Many scholars have labored loyally to bring to light major figures like Lois Weber [4] and Albert Capellani [5], but these revelations remain niche tastes. Kristin and I have done our bit on the blog, in many entries and in the video lecture “How Motion Pictures Became the Movies.” [6] That suggests that today’s film industries, film culture, and artistic options have their sources in this era that, in retrospect, teems with creative possibilities.

The sheer imaginative variety of this output is brought home to me virtually every time I go back to see something recently discovered. My extended stay at the Library of Congress Kluge Center back in early 2016 was a smack on my head. In America, while filmmakers were elaborating the “continuity” system of storytelling (still with us), they were also pursuing side paths and fresh possibilities. (To check, start with “Anybody but Griffith” [7] and move to later entries.) My discoveries complemented my years of visiting European archives to investigate both major auteurs and little-known films. (See the category “tableau staging.” [8]) Now these releases, courtesy of Gaumont (Tih-Minh) and the cooperative efforts of Amsterdam’s Eye Filmmuseum [9], Milestone Film and Video [10], and Kino Lorber [11](Filibus) offer some new angles on the period.

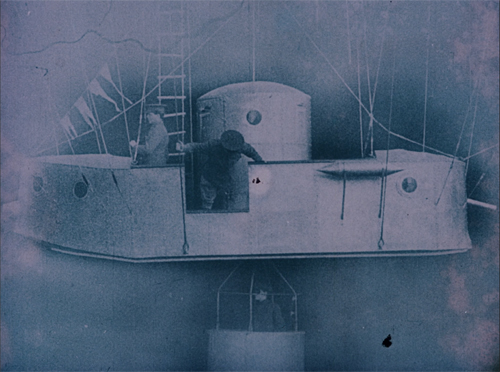

Filibus centers on a supervillain who, unlike Fantômas or Dr. Gar el-Hama, is a woman. Like them, she’s a master of disguise, appearing as a genteel lady but also a suave gentleman and a sleek masked marauder. She steals jewelry through the usual methods: casing a household, sizing up the spoils, and confounding the authorities. What sets her apart is that she travels in a midsize airship that allows her to move swiftly from place to place and lower herself in a gondola to the numerous balconies that give access to the treasures.

She’s also adept at outsmarting the detective Kutt-Hendy. Exploiting the current public fascination with pseudo-scientific detection, the film shows her capturing his fingerprints on a rubber glove, and then leaving them at the scene of the crime. But she has old-fashioned tools as well, including a mysterious knockout scent.

Capably if unspectacularly directed by Mario Roncoroni, the scenes are mounted in straightforward ways for the period. Cutting, as you’d expect, consists largely of linking scenes or occasionally enlarging a detail we need to see, such as a camera inside the eye of a cat statue.

Within dialogues, simple axial cuts give us access to actors’ expressions. Sometimes Rondoroni moves a figure closer to the camera without motivation, simply to show us things more clearly, before the figure then retreats a couple of steps.

This is an anachronistic device, common in much earlier films. Most directors of the period motivated such movements by having something in the foreground that would draw the actor nearer to the camera.

The preposterousness of it all is well-recognized by everyone concerned, I think. The most impressive set, a parlor boasting Egyptomania galore along with the supposedly ancient but highly inauthentic cat sculpture, gets a good workout during the crime and the investigation. What remains, though, is Filibus’ unique transport system that allows her to bypass all the driving down roads and clambering up building facades we get in Feuillade. A blimp and a basket do the trick, leaving Filibus to sail off to her next conquest.

The film was noted as over-the-top in its own day. One critic wrote: “Great drama of adventure? Say rather a great cinematic mess of adventures. . . .” Evidently the tackiness of the special effects was evident as well. But we’re lucky to have it as one more document of the sometimes overstrained efforts to pack fresh sensations into the still-emerging format of the feature film.

Opium and murder

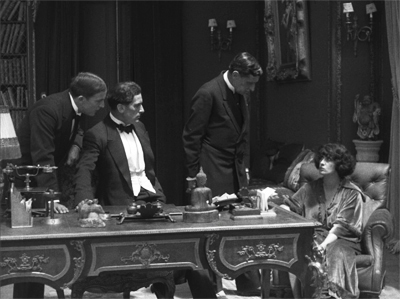

Signori giorati… is more orthodox and, I think, more satisfying as a story. A classic salon melodrama with plenty of diva posturing, it shows the decadence of the very rich brought to account. The adventuress Julienne (originally Lina) Santiago has seduced Dr. Nancey into setting up a plush opium parlor. Every night, the rich come to the “House of Forgetfulnesss,” where Julienne and the doctor blithely pick their pockets. When the police get interested, Julienne betrays Nancey and bolts, later to take up with one of their clients, the Marquis de Vallier. He resolves to marry her and brings her home to meet his daughter Helène (Valeria Creti, aka Falibus) and her husband. A deadly intrigue begins.

Signori giorati… shows the pluralism of visual expression of the period. While depth staging isn’t much developed here, the vast opium-den set carries the action far into the distance, where Julienne, masked, awaits the Marquis (above). Later, lurking in the reeds, Julienne stalks Helène’s husband.

Courtroom scenes in 1910s films are surprisingly varied, and director Giuseppe Giusti offers an unusual array of angles on the action.

A split-frame flashback illustrates courtroom testimony.

None of these moments is extraordinary for the period, but they nicely exemplify visual strategies becoming normalized in European cinema. Likewise, the somewhat awkward linkage between the first section around the opium den and the second on the Vallier estate show the need to tighten up the overall arc of the narrative–a problem European films would face for some years.

An unusual feature of the disc is the inclusion of five short films from the Amsterdam premiere of Filibus in 1918. This was made possible by the Eye Filmuseum’s splendid collection of early films from around the world shown in the Netherlands by the distributor Jean DeSmet [23]. There’s also a brief short giving background to that collection.

From Vietnam to the Riviera

Tih-Minh (1919) followed in the wake of Louis Feuillade’s successful serials Fantômas (1913-1914), Les Vampires (1915-1916), Judex (1917), and La Nouvelle mission de Judex (1918). Released in installments from February to April 1919, Tih-Minh followed an important Feuillade feature, Vendémiaire, released in January. Throughout the same years Feuillade signed dozens of shorter comedies and dramas. Not only was he an efficient director on a scale we can hardly imagine today, but he had a powerful incentive: Gaumont gave its top directors a percentage of a film’s revenues, and Feuillade’s salary made him wealthy.

The plot revolves around a treasure supposedly hidden in Indochina. But where? A Sanskrit book contains notes, in code, about its whereabouts. The explorer Jacques d’Athys has unwittingly acquired it during his last expedition. Learning this, former German spies Kistna the “Asiatic” and Dr. Gilson recruit the hapless Marquis Dolores (above) and target Jacques’ villa in Nice. Jacques has also brought back the delicate young woman Tih-Minh (also above), daughter of a French colonist murdered, it’s revealed, by Gilson (né Marx!). The complications around the coded message lead the gang to a series of raids on the household, usually involving efforts to kidnap Tih-Minh. The efforts are resisted by our heroes–Jacques, his loyal servant Placide, the maid Rosette, and the British diplomat Sir Francis Gray.

Tih-Minh has an essentially comic structure. Unlike Fantômas and the Vampires, this gang can’t catch a break. Nearly every attempt they make, involving poisons, amnesia serum, hypnosis, and accomplices smuggled into the household, is thwarted, quickly or eventually. The ineptitude of Kistna’s gang is nearly matched by the passivity of Jacques’ team. They seem to wait around for the next assault, and when they prepare a trap, it usually fails. Only Placide, consistently suspicious, mounts countermeasures. Just when you wonder whether Nice has a police force, Jacques announces they can handle things best themselves.

Tih-Minh, a favorite of mine over the years, cracked a bit on this go-round. For the first time I found the opening installments dilatory and meandering. Feuillade is counting on our enjoying the company of these comfortably rich people and their rounds of coffee breaks, walks on the estate, and flower-picking in dazzling sunlight. And it is a kind of Bower of Bliss, which will eventually host three weddings.

Unlike the earlier serials, where he relies on composition in depth [25], here he favors lateral layouts. It’s as if the speed of the production pressed him toward lining up characters talking to one another in long-shot and medium-shot. Yet as I wrote about here [26], he varies the placement of heads in graceful waves.

These framings look forward to his later work’s “long-take” setups, broken only by dialogue titles.

The pacing and flashy visual invention pick up considerably in the later installments, when Feuillade hurls his cast through the magnificent landscapes of the Riviera. During the war, Gaumont moved substantial portions of production to the Victorine studios in Nice. Installing himself there in 1918, Feuillade takes advantage of everything in the neighborhood. You can sense his delight in finding ways to use the ocean front, rocky terrain, gorges, mountain crags, decrepit hilltop castles, luxurious estates, and hotel rooftops.

Pursuits across these forbidding spaces are a powerful attraction in their own right, and the second half of the film does not disappoint. For some shots the camera seems a mile away from the tiny human figures.

The actors accordingly give their all. Placide’s physical comedy is matched by his willingness to be beaten up, dropped from a great height, or folded up into a trunk lashed to an automobile roof. Flung into the ocean, he laughs it off.

Heroes and villains alike are willing to clamber around scaffolding and window ledges and crawl down the face of a mountain.

Mary Harald as Tih-Minh, apparently a wilting flower, seems game for anything as well.

We’re so used to stunt doubles for action scenes that we forget that long ago actors were athletes.

The vertiginous spaces and the bravado of the performers come to a climax when the chase moves to a zipline carrying rock from a quarry down into a valley. The villains dive into one of the gondolas and ride off to infinity. Undaunted, our heroes follow.

These shots, a rebuke to the cheesiness of Falibus‘ special effects, are alone worth the price of a DVD. And you thought Preminger treated actors roughly?

One more aspect of this release makes it a must-have for admirers of early film. It is one of the finest digital transfers of a silent film to disc that I have ever seen. Derived from a pristine negative, it is a perfect illustration of what 1910s cinema looked like at its best. (Thankfully, it is not tinted. Tinted versions often smudge original photographic detail.) We always knew that there was more on a 35mm orthochromatic film than we could see. Now we see it.

Gaumont’s disc of Tih-Minh is coded for all regions and contains optional English subtitles. Unless a US distributor picks it up, it will be available only at places like Fnac [34] and Amazon.fr [35]. University libraries and film departments should be able to get copies easily. Beware the bootleg version of the Belgian print (the source for the restoration’s intertitles) offered on eBay and elsewhere.

The Italian cinema of the 1910s was no less stylistically innovative than that of other nations, but the films haven’t achieved canonical status. Except for big, influential productions like Cabiria (1914), the output of this major industry has been overlooked, largely for reasons of availability. A breakthrough came with the superb collection, Italian Silent Cinema: A Reader [36], ed. Giorgio Bertellini (New Barnet: Libbey, 2013). My amateur forays into the area have yielded some nifty items, such as Fabiola (1918) and Maman Poupée [37] (1919) and Il Maschera e il Volto [38] (1919), as well as many I hope to share in the future.

Critical response to Filibus is sampled in Vittorio Martinelli, Il cinema muto italiano 1915, part 1: I film della grande guerra (Rome: Bianco e Nero, 1992), 190-192.

The standard study of Feuillade is Francis Lacassin’s magisterial Louis Feuillade: Maître des lions et des Vampires (Pairs: Bordas, 1995). (It’s a real bargain here [39].) I survey Feuillade’s staging strategies in Chapter 2 of Figures Traced in Light. A more general account of silent film staging in depth is in Chapter 6 of On the History of Film Style.

Not incidentally, the Eye Filmmuseum offers a rich array of films from many periods, [40] including the 1910s, for free viewing online.

Tih-Minh (1919).