DB here:

Our newest installment of Observations [2] is now up on The Criterion Channel [3]. In it I consider how Ozu’s Passing Fancy (1933) exhibits his distinctive methods for treating a scene’s space. Now, here’s a preview for a little bonus that will show up there next week. It’s a short on how Ozu sometimes relied on sound in a silent film.

You probably know about Japan’s katsuben, or benshi. He or she stood alongside the screen and accompanied the film–explaining the action, commenting on it, and imitating the characters’ voices while reciting the intertitles. The benshi were usually given scripts for the titles’ texts, but they were also expected to expand on them.

Benshi became celebrities, as strong an attraction as the movies, and they wielded power over some production companies. Benshi might reedit films to suit the performance they wanted to give. One reason that talking pictures came only gradually to Japan was the resistance of the benshi associations to being put out of work.

Filmmakers who resented the benshi’s power seemed to have sought to make the films as free-standing as possible. One strategy was to have many intertitles, which served to anchor the meaning of a scene. More positively, in Ozu and the Poetics of Cinema I argue that the presence of a benshi gave filmmakers new storytelling opportunities.

Knowing that the benshi would be speaking the lines in the intertitles, filmmakers could make those titles quite short, creating a swift rhythm. (Contrary to some impressions, Japanese silent movies aren’t slow; even dialogue scenes are likely to be cut fast.) Moreover, the benshi could make conversations more compact than what we find in American films. Instead of a pattern of speaker/title/speaker/listener, your shots could run: speaker/title/listener.

Just as important, filmmakers could count on the benshi to fill in things not shown onscreen. That could allow for some unusual interaction between images and speech.

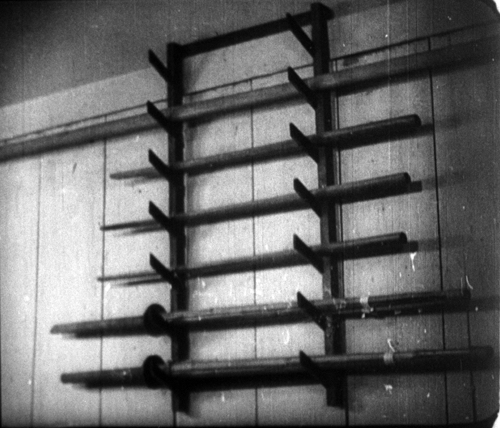

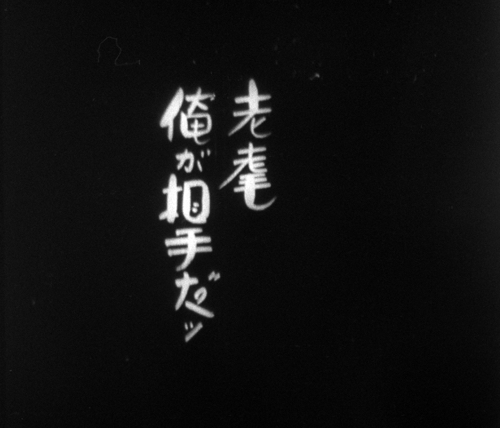

For example, Iwami Jutaro (1937), a swordplay comedy, treats one scene with “offscreen” sound. A bully is watching a kendo match. Cut to the rack of kendo swords, followed by a cry from one fighter, given in an intertitle: “Fool, you’ll be fighting me!”

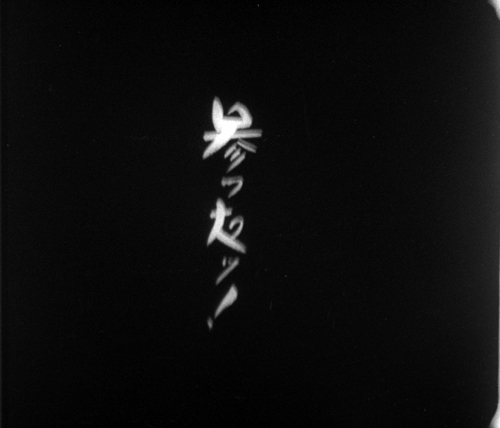

Cut back to the rack collapsing, as if shaken by the fight. Another title: “I give up!” is followed by a shot of a fallen fighter, beaten.

The shot of the fallen bully anchors the title, but in the flurry of shots we’re invited to imagine the skirmish. Very likely the benshi was shouting the lines while the accompanying music whipped up a burst of excitement. This elliptical treatment of the match suggests that Kurosawa’s Sugata Sanshiro, made only a few years later, was heir to a tradition of off-center rendering of martial-arts combat.

Ozu recruits the benshi for something more ambitious, as I try to show in this bonus. Regrettably, we couldn’t find usable stills of benshi performances from the period, so the stills illustrate modern revivals. Also, I still haven’t seen Suo Masyuki [9]‘s recent Talking the Pictures (Katusben!, 2019) [10], a comedy about benshi culture.

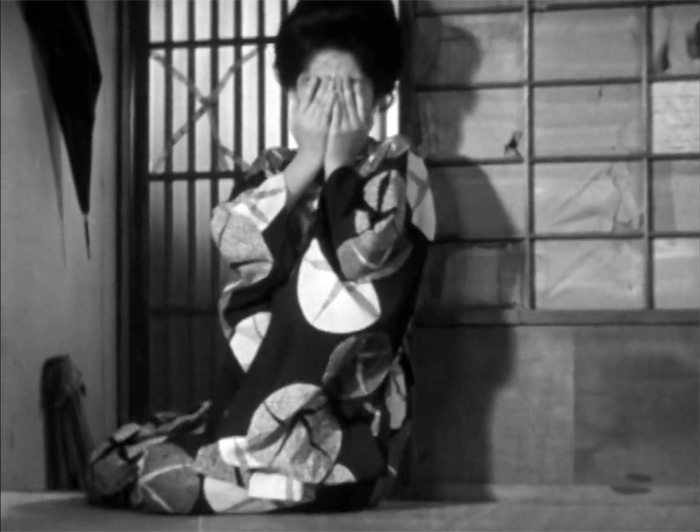

Anyhow, a little analysis of what we have enables us to appreciate how Ozu uses the benshi to emphasize character reactions. The highlight comes in an emotional climax, when the benshi’s sobs would have filled in offscreen action.

Ozu, a fan of Western cinema, would have seen talkies and realized the power of offscreen sound. But I suspect he didn’t need external influences to understand that the benshi’s patter gave directors great freedom in visual narration.

Passing Fancy is one of three masterpieces Ozu released in 1933. (The other two, Dragnet Girl and Woman of Tokyo, are also on the Channel.) The Japanese cinema of this period was one of the glories of world filmmaking, with talent at all levels. Still, very few directors anywhere matched Ozu’s quietly outrageous innovations in form and style, his urge to show us cinema, and so the world, in a poignant, exhilarating way.

Thanks to Kim Hendricksen, Peter Becker, Grant Delin, Erik Gunneson, and the team at Criterion for enabling me to include this clip on our site. Thanks also to Komatsu Hiroshi for information on Iwami Jutaro and Steve Ridgely for correction of one of the intertitles.

For more on the benshi, see the comprehensive study Benshi, Japanese Silent Film Narration, and the Forgotten Narrative Art of Setsumei: A History of Japanese Silent Film Narration [11], by Jeffrey A. Dym (Edwin Mellon Press, 2003). Fascinating background on the struggles between the benshi and other sectors of Japanese film culture can be found in Joanne Bernardi, Writing in Light: The Silent Scenario and the Japanese Pure Film Movement [12] (Wayne State University Press, 2001) and Aaron Gerow, Visions of Japanese Modernity: Articulations of Cinema, Nation, and Spectatorship, 1895-1925 [13] (University of California Press, 2010).

Another intriguing review of Talking the Pictures is Jessica Klang’s in Variety [14].

Ozu and the Poetics of Cinema is available for free download here [15]. (Be patient; the file is big.) An earlier Observations [16]segment considered Kurosawa’s cutting of martial-arts action, and a blog entry [17] developed that a bit more.

Another way to make a silent talkie is discussed in this entry [18] on The Donovan Affair.

Passing Fancy (1933).