DB here:

If you’re not a hardcore horror fan, you may not recognize the image that adorns this year’s Torino Film Festival [2]publicity, but I bet you’re fascinated by it anyway. Barbara Steele, the diva supreme of 1960s scary cinema, is a fitting emblem for this year’s broad and deep retrospective of the horror genre. From The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920) to Dr. Jekyll and Sister Hyde (1971), thirty-six films are on display, often in 35mm prints. Emanuela Martin, the curator of the series and director of the festival, has created a book devoted to her program. [3] And the festival has welcomed the iconic Ms Steele as a guest.

In-depth commitment to a retrospective is typical of this enterprising festival. Kristin and I had been hearing about it for years from our friend, Wisconsin Cinematheque honcho Jim Healy, who has long been a contributing programmer here. Previous editions focused on “Amerikana,” De Palma, dystopian SF, Powell & Pressburger, and Miike Takashi.

Still, at Torino as elsewhere, the emphasis falls on new work. Dozens of films are screened both in and out of competition. Kristin and I are still assimilating items to report on in forthcoming blog entries. But we’ve already sampled the charms of this city, not least its monumental temple to film, its Museo del Cinema. But first, another municipal tribute to picture-making.

Pictures, some puzzling

The Galleria Sabauda [4] in the Palazzo Reale teems with masterpieces, mostly from the collection of the Savoy dynasty. The non-masterpieces are worth studying too, and some, even in their weirdness, can prompt thinking about cinema (of course).

For instance, there’s this Antonio Tempesta painting, Torneo nella Piazza del Castello (1620), showing an aristocratic wedding procession in a Turin plaza. I liked its steep perspective with the commanding figure of the warrior in the foreground. Close observation, which the Sabauda permits, reveals tiny figures on the rooftop at the left.

Evidently the paining yields a lot of information about architectural projects of the day. All I could think of is what a swell film shot it would be.

Instead of Testa’s high angle, which yields a centered and stable composition, consider Varallo’s punchier Saints Peter and Mark, from the same period (1626).

The low viewing angle on the two saints makes their muscular gestures dominate the middle of the format. That axis calls to their incredibly distended fingers caught in the act of dictating and writing. The angle also lets us enjoy the casually crossed leg of Mark and his tense, splayed toes, which seem to poke against the picture surface.

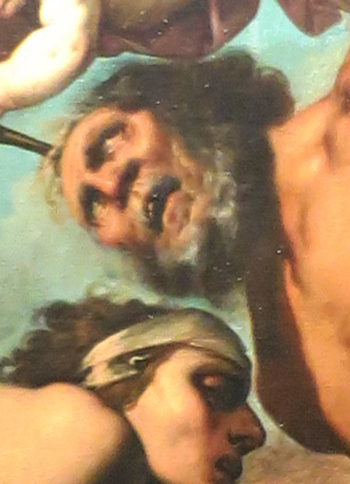

Angles again: This unidentified painting of the savage martyrdom of Saint Bartholomew (ca. 1635) grabbed me because of its even steeper low angle.

Apart from the Caravaggio spotlight effect (overexposed in my shot; I can’t find an image online), it reminded me of one of my fussier concerns.

Cinema lets us separate planes because of constant overlap, one layer of space moving against another. Painting can’t let us detect contours from movement, so when painters want to shove figures together they need to mark off overlapping planes in other ways, such as color or edge lighting.

Alternatively, painters can pack figures but leave little holes that let bits of background show through but still give a sense of movement. In the St. Bartholomew painting, the contours that specify the figures nearly graze each other.

I especially like the way that the brow and nose of Bartholomew’s tormentor fit like a puzzle-piece into the twist of the saint’s shoulder. Good old figure/ground technique, but pushed to a kind of minimal limit.

When these little gaps aren’t left, and only overlap and colors pick out planes, you can get some striking effects. The most mind-bending thing of this sort I saw at the Galleria was this Resurrection, perhaps by Antonio Campi, from around 1660. At the bottom of the picture a soldier is prodding a sleeping guard beside the sepulcher.

The soldier on the right is one strange creature. You can work it out that he’s wearing a thick, ribbed yellow doublet with a beast’s head attached at the shoulder. But the effect of the overlapping planes and the compositional contours is of a duck/rabbit shift [11], as if the beast is bent over the soldier.

The effect is enhanced by the sinewy leg of the soldier behind, which seems at first glance to be the right arm of the stooped beast. The absence of spacing between the foot and the spear helps the effect of a limb continuing the arc of the bent back.

Enough of amateur art appreciation. Turin houses another magnificent repository of artifacts, this one dedicated to our own obsessions.

Film history on a grand scale

Mole Antonelliana, Turin.

The Museo Nazionale di Cinema [14] is housed in the Mole Antonelliana [15], a fascinating elongated building that towers over the city. An elevator shoots people up to a fancy spire with a panoramic view.

Pictures can’t do justice to the Museo inside. You enter through the biggest and most engaging collection of pre-cinema materials I’ve ever seen. Nearly every gadget, from the magic lantern to Edison’s Kinetoscope, is offered for you to tinker with. (An interactive sampling is here [16].) Once you’ve seen the entire archaeology of film, you step into a gigantic hall with a spiral ramp leading to level after level.

Nearly the first thing you meet is the god Moloch from Cabiria (1914), a film made when Turin was a major national production center. Not quite as big as in the film, he was enough to intimidate me.

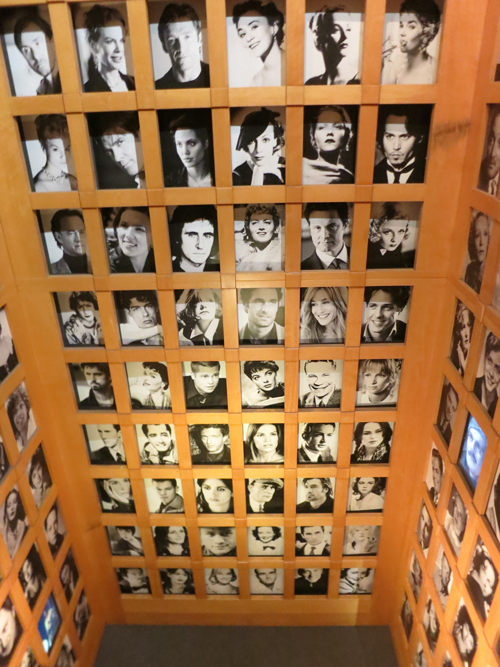

Various floors take you to theme areas. There’s one on film production with some classic cameras, another displaying a vast gallery of posters, and several devoted to changing exhibitions. (The current one was on facial expression in cinema, hooking to a big show of Lombroso’s physiognomic studies [19].) You can see a script page from Psycho or Citizen Kane, and stare in awe at a two-story display of star portraits.

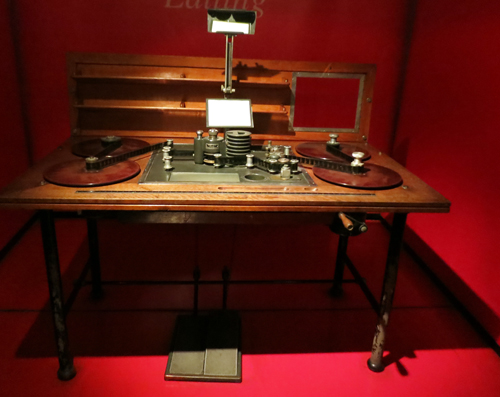

Kristin and I visited a shrine to the beautiful Prevost editing table. (This is a 1930s one.)

There’s so much here that more than one visit is probably demanded. In all, the Museo makes a splendid anchoring point for the film festival. We’ll tell you more about that in upcoming entries.

We wish to thank Jim Healy, Emanuela Martini, Giaime Alonge, Silvia Saitta, Lucrezia Viti, Helleana Grussu, and all their colleagues for their kind help with our visit.

For more Torino images, visit our Instagram page [22].

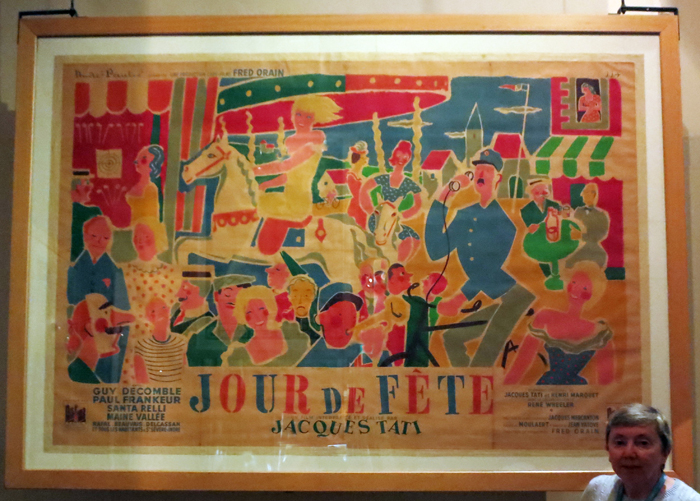

Kristin and a big poster for Tati’s Jour de fête.