DB here:

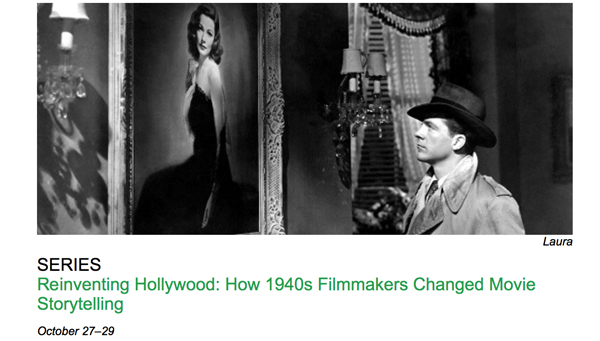

Next weekend Astoria’s wonderful Museum of the Moving Image [2] is sponsoring a series of films keyed to my book Reinventing Hollywood. The program consists of Laura on Friday, A Letter to Three Wives and Unfaithfully Yours on Saturday, and Our Town and Portrait of Jennie on Sunday. Here’s the schedule. [3]

I’ll be giving a talk before Three Wives and will hang around for conversation and book-signing afterward. If you’re in the vicinity, why not come by? Note: Four of the five screenings command 35mm prints! If you’ve only seen Our Town in the horrendous public-domain video versions, you’re in for a treat, because it looks (and sounds) superb in 35. Then again, there’s that tidal-wave ending to Portrait of Jennie, a force of nature on the big screen.

Looking better than when he made it?

Beyond Glory (1948). Production still.

Actually, this entire clutch of classics is pretty fair sampling of the audacity of the period, an age when narrative delirium was welcomed. Of course a lot of A pictures were stodgy, but there were an unusual number of both popular hits and less-successful items that are engagingly experimental.

The book, as Tony Rayns remarked [5] in his Sight & Sound review, ventures beyond the classics. I cover all the films in the MoMI program, but a lot of space is devoted to minor movies too, a fair number of B films and plenty of “nervous A’s.” Those nervous A’s–films trying to get by on less-known stars, unfamiliar source material, or just a strange premise–provided me with lots of examples.

A friend who likes Reinventing Hollywood said that it was too bad I had to spend so much time on obscure and second-rate movies. It’s true that in viewing I slogged through quite a few dogs. Most weren’t illuminating, but some were, and I slid them into the manuscript, even if the reader was unlikely to have heard of them.

But two factors pop up here. First, I wanted to show just how pervasive the newly popular storytelling techniques were. That meant considering items outside the canon. When you think of complicated flashback films, you don’t think of Beyond Glory (1948) and Backfire (1949), though they may be the most intricate time-shuffling movies of the period. If you arrange the past-time events in the order we see them, Beyond Glory gives us 10-9-8-1-4-3-5-6-7-2. In Backfire, the order of presentation is 3-5-2-4-1-6-7.

These show a very 40s development: By then, such time schemes were becoming commonplace. Moreover, the fact that these two films come at the end of the decade is itself of interest. Was there a kind of arms race to tell stories in ever more elaborate ways?

Looking at the less-known items can also yield a sense of the limits of innovation. Sometimes these movies went too far. One critic noted of Beyond Glory that it “moved slowly and confusingly through a great many flashbacks.” As for Backfire, even the director Vincent Sherman had qualms:

That picture had an involved story, with flashback-within-flashback, and I hated it. The interesting thing is that not long ago I saw the film, and it looked better than when I made it.

Sherman’s last remark is indeed interesting. Today, after the really fragmentary flashback constructions we find in films from the 1990s onward, films like these (and The Locket and Passage to Marseille) don’t look as ornery. Any day now you may hear from a Tarantino fan that Backfire is a masterpiece.

More broadly there’s an issue of method, and it’s controversial. I suspended matters of quality to an unusual degree. Of course the book talks a lot about bona fide classics. I praise films by Preminger, Ford, Hitchcock, Welles, Mankiewicz, Sturges, et al. But I stubbornly persist in believing that we can best understand their accomplishments in the context of the broader burst of storytelling strategies that swept through the 1940s.

True, great writers and directors provided some of the energy for that burst, but they didn’t work alone. I think, for instance, we appreciate It’s a Wonderful Life better if we know about conventions of voice-over narration, angelic intervention, and flashback construction that had already crystallized when Capra and his screenwriters gave them a new spin.

A lot of researchers suspend questions of value in order to bring to light other factors. Scholars studying gender, race, and ethnicity consider films of all levels of quality representing women or African Americans or Jewish culture. Students of genre often find that lesser-known Westerns or musicals shed light on certain conventions. Even failures can be instructive.

Reinventing Hollywood pursues a similar method but on an area of creativity less commonly considered: narrative. The book tries to trace both common and offbeat strategies of plot construction and narration–at a period when innovation in those domains was rewarded. In some instances, we get striking innovations more or less by accident [6].

In sum, I was more interested in reconstructing the major and minor storytelling options of the period than in picking out masterpieces. Going into the kitchen to watch the menu being devised, you might say, rather than savoring a few consummate meals. That meant bulk viewing, which yielded a bulky book (but a good bargain at the price).

Some day it would be fun to mount a series of intriguing second-tier items I ran into. They’ll never be classics, but they do shed light on my research questions. Apart from completists, there are fans who would enjoy seeing things that are elusive on video and never make it to repertory screens or archive retrospectives. The problem then, as for me, was finding prints….

Thanks to David Schwartz and his colleagues for arranging this event at MoMI.

Backfire (1949).