Ohayo (Good Morning, 1959).

DB here:

Ohayo (Good Morning, 1959) was the first Ozu film Criterion released on DVD, back in 2000 [2]. The DVD format, launched in 1997, really took off only after The Matrix disc was released in September 1999. So it’s not surprising to find the Ohayo edition quite sparse. No extras, no booklet, just a brief appreciation by Rick Prelinger (which can be read here [3]). One note is charming: “To switch between the menus and the movie, use the menu key on your remote. Use the arrow keys to cycle through menu selections. Press enter/select to activate the selection.”

[4]That early edition wasn’t bad, but now Criterion has given us a brand-new one [5]. It’s derived from a 4K digital restoration and looks like a million bucks. Included with it is a pristine edition of I Was Born, But… (1932), Ozu’s first indisputable masterpiece (though I’d put Tokyo Chorus of 1931 very close), and what scraps remain of A Straightforward Boy (1929). So we have three of Ozu’s kid movies in one neat package, available in standard DVD or Blu-Ray.

[4]That early edition wasn’t bad, but now Criterion has given us a brand-new one [5]. It’s derived from a 4K digital restoration and looks like a million bucks. Included with it is a pristine edition of I Was Born, But… (1932), Ozu’s first indisputable masterpiece (though I’d put Tokyo Chorus of 1931 very close), and what scraps remain of A Straightforward Boy (1929). So we have three of Ozu’s kid movies in one neat package, available in standard DVD or Blu-Ray.

The disc includes a shrewd and funny video essay by Shadowplay [6]‘s David Cairns about Ozu’s humor. I’m there too, in an illustrated interview called “Ozuland.” The title derives from my suggestion that like Bresson, Tati, Mizoguchi, and a few other ambitious directors, Ozu created his own distinct artistic realm. That realm touches recognizable real life at many points, but it has been purified–maybe decanted would be a better word–by means of cinematic form and style.

My enjoyable talk with Elizabeth Pauker ranged on a lot of topics across two hours. We talked about the film’s themes, chiefly the role of language in easing day-to-day human interaction. We discussed Ozu’s distinctive camera positions (yes, there are more than one), his compass-point cutting (360-degree space, 180-degree reverse shots), and his use of adjacent spaces and rhyming compositions. We talked about his narrative strategies too, particularly his oscillation between nuclear-family plots like I Was Born, But… and extended-family ones like Brothers and Sisters of the Toda Family (1941, another masterpiece) and Tokyo Story (1953, ditto).

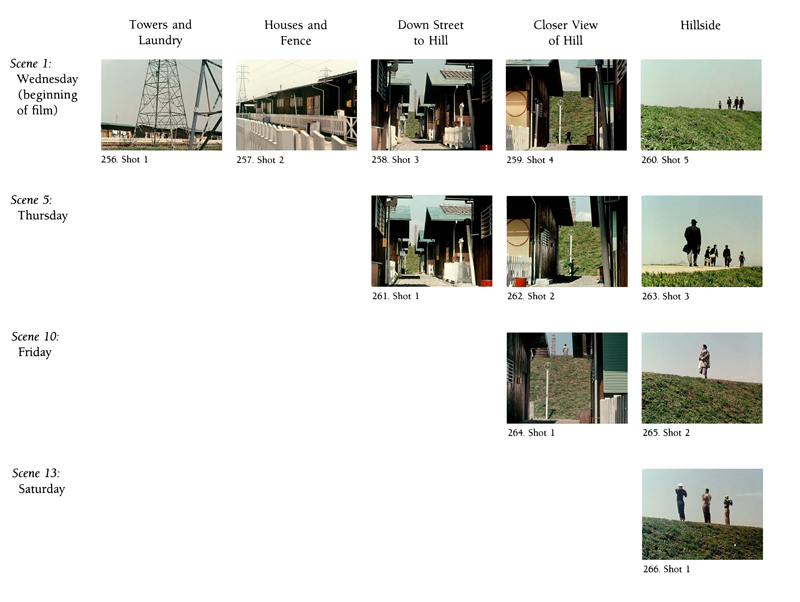

I emphasized both the film’s humor and its status as an unexpectedly experimental work; Ozu was setting himself new problems. How do you treat a neighborhood as an extended family? How do you shoot families living jammed together? How do you accentuate comic misunderstandings, and create gags through composition and color?

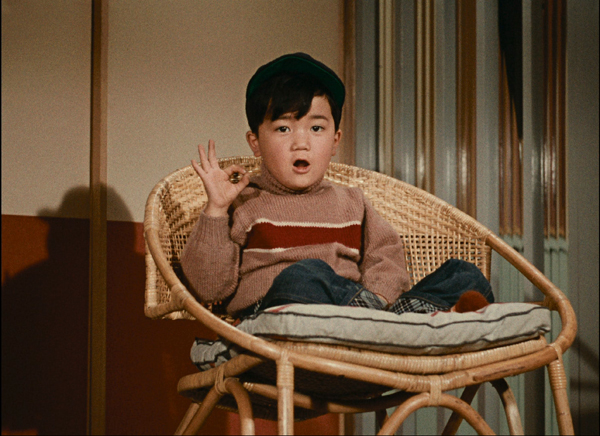

And how do you structure a film around a landscape, days of the week, and neighborhood routines? Ozu’s answer: Through echoic camera positions and compositions. Here’s an anatomy, showing the first four days’ scene openings.

Not all of our conversation could be included in the final cut, of course. For more on these and other matters, you can download my book Ozu and the Poetics of Cinema [8]. (The pattern shown above completes itself on p. 353.)

The title of that book resonates in a couple of ways. Most obviously it’s meant to show that a systematic approach to form, style, and theme (the stuff of a poetics of any artform) can illuminate what Ozu’s up to. The title also has personal meaning, because it was Ozu who taught me just how deeply cinematic patterning could penetrate the texture of a movie. Without sacrificing any emotional power, Ozu created films that are marvels of organization, from large-scale story construction to the smallest detail of image and sound.

I remember distinctly when I realized the grain of this work. One night back in the mid-’70s, Kristin, Ed Branigan, and I were watching Ohayo for the first time, on a 16mm New Yorker print. We came to a simple transitional passage and we all gasped. I dove back to the projector and ran the cut backward and forward again.

Apart from shifting us to a new space, as required by the plot, and apart from giving us two exquisite compositions, Ozu added a grace note: the red accent that appears in the same area of the two shots, linking shirt and lampshade. This discovery led Kristin and me to formulate the idea of the “graphic match,” a term for what happens when patterns of line or mass or color coincide from shot to shot.

Some directors, from Lubitsch to Brakhage, had employed graphic matches. Eisenstein had formulated the idea theoretically. But Ozu gave us a demo en passant, in the course of just “following his story.” His match isn’t necessary for the action, but like a rhyme in a narrative poem or a decorative trill in an operatic aria, it adds a sparkle to the moment.

By rewarding minute attention, Ozu made me realize that even ordinary movies teem with pictorial possibilities. There’s potentially so much going on within any shot or cut that scrutiny is often worth your time. True, studying Ozu makes most filmmakers look wasteful. They miss opportunities to enrich all the dimensions of cinema they present, to load every rift with ore.

But if we want to know how films work and work on us, we need to make the effort of looking closely. You’ll almost always find something interesting. When I consulted several books on 1910s directors like DeMille and Taylor [11], I found that nobody talked about things that popped out at me [12]. As Yogi Berra said, “You can observe a lot by watching.”

Just how cunning was this guy? The more I looked, the more I began to hallucinate that he had made his movies just for me. When he returned to a scene’s master shot, I found that he had cunningly shifted the framing a little, or rearranged tiny elements of the set (often a beer bottle). He must have known I’d take frame enlargements (in that analog age) to check one image against another. I’d notice that in what seemed a perfectly orthodox reverse-angle sequence, things in the background had been slightly shifted to create a variant composition. That red lamp in Ohayo appears teasingly in the distance, out of focus, when other things are going on. Then you have the fact that people in these films like to keep their drinks at the same level of fill, no matter how big the glasses are or how close they are to the camera. Color seems to have inspired him to try these tricks, as in his first color film Equinox Flower [13](1958):

As with the shirt and the lampshade, there seemed to be Easter Eggs designed not just for my “critical method” but for me, the obsessive analyst. Why? Why would a grown man put these in his movies?

For fun. This tendency isn’t the punishing pursuit of structure at all costs we find in, say, Peter Greenaway. It’s the realization that you can play with patterning cinematic techniques, using them to accessorize your plot, the way musical motifs deepen the dialogue of an opera. And so what if nobody much notices? As I tell my skeptical students: If you thought of it, you’d do it too, just to get away with it.

Ohayo has another of my favorite examples. Throughout the film, the power lines near the neighborhood become a pictorial motif. At one point, the elderly Mrs.Haraguchi seems to be praying to a tower in the distance.

The film starts with a long shot of the neighborhood, its rooftops and fence and washlines in the distance, all dominated by a tower. The film ends with a shot of wash on a line, paying off the gag of the boy who constantly shits his underwear. But the angle of the shot constitutes a reverse angle of the very first shot, since the towers are now in the distance.

Given Ozu’s penchant for 180-degree shifts, and the rigorous patterning of his transitional spaces in the film, I stubbornly, maybe foolishly, maintain that he found this a neat way to give spatial closure to his movie, independent of the underpants gag in the foreground.

Ozu provided me bonus materials in his movies. Some are perhaps visible only to someone as persnickety as he was. And maybe they don’t matter. Ozu gives us so much to enjoy that to ask for more would be churlish. Yet he gives us that more without our asking. His films are generous to their characters and to us, but also to the art of cinema. His absurdly “restricted” approach opened onto vistas of possibility that promise more enjoyment than we have a right to expect.

He had an engineer’s mind, a painter’s eye, and a novelist’s human empathy. And he accomplished it all within one of the most flagrantly capitalistic film industries, which populated Ozuland with stars and stories. Taken all in all, I bet he’s the greatest filmmaker who ever lived.

Thanks to Elizabeth Pauker, who produced “Ozuland,” and as ever Peter Becker and Kim Hendrickson. They have done themselves and Criterion proud with this wonderful package.

The fussbudget in me can’t resist correcting something that comes up in the promotional materials and in some reviews. Ohayo wasn’t filmed in Technicolor. Ozu used what was called “Agfa-Shochikucolor.” I believe that’s just Agfa film with Shochiku adding its brand name, the way “Metrocolor” was MGM’s Eastmancolor. Why Agfa? Ozu explains: “Red turns out magnificently on Agfa film.”

I supplied a feature-length commentary for another Criterion trip to Ozuland, An Autumn Afternoon [18] (1962). If you decide to download Ozu and the Poetics of Cinema, be patient. It’s a big file. Lots of pictures.

Ohayo (Good Morning).

P.S. 30 May: An extract from my interview, focusing of course on farts, is on Criterion’s YouTube channel [20].