The Shape of Night (Nakamuro Noboru, 1964).

DB here:

I didn’t plan it that way, but it turns out that a great many films I saw at this year’s Hong Kong International Film Festival would have to be categorized as genre pictures. Not, admittedly, Shu Kei’s episode of Beautiful 2014, which interweaves flashbacks and erotic reveries in a purely poetic fashion. And not Tsai Ming-liang’s “sequel” to Walker (2012, made for HKIFF), called, whimsically, Journey to the West. Here again, Lee Kang-sheng, robed as a Buddhist monk, steps slowly through landscapes, some so vast or opaque that you must play a sort of Where’s-Waldo game to find him. (You have plenty of time: there are only 14 shots in 53 minutes.)

But there were plenty of other films that counted as genre exercises. Yet they mixed their familiar features with local flavors and fresh treatment, reminding me that conventions can always be quickened by imaginative film artists.

Keeping the peace, in pieces

Black Coal, Thin Ice (2014).

Take, for instance, The Shape of Night, a 1966 street-crime movie from Shochiku, directed by Nakamura Noburo. Nakamura was the subject of a small retrospective [3] at Tokyo’s FilmEx last year, and this item certainly makes one want to see more of his work. A more or less innocent girl falls in love with a yakuza, who forces her to become a prostitute. In abrupt, sometimes very brief flashbacks, she tells her life to a client who wants to rescue her. The film makes characteristically Japanese use of bold widescreen compositions, disjointed close-ups, and mixed voice-overs from her and the men in her life. In retrospect, everything we’ve seen has been seen in other movies, but Nakamura’s handling kept me continually gripped and often surprised.

Or take That Demon Within, a Hong Kong cop film that premiered at the festival’s close. Dante Lam has made several solid urban action pictures, especially Jiang Hu: The Triad Zone (2000), Beast Stalker (2008), Fire of Conscience (2010), and The Stool Pigeon (2010). They’re characterized by wild visuals and exceptionally brutal violence, and That Demon Within fits smoothly into his style. The new wrinkle is that a boy traumatized by the sight of police violence himself becomes a cop. He’s then haunted by the image of the cop from his past, while he’s also caught up in a search for a take-no-prisoners robber.

His hallucinations and disorientation are rendered through nearly every damn trick in the book, from upside-down shots and blurry color and focus to voices bouncing around the multichannel mix.

There are dreams, too (seems like almost every new film I saw had a dream sequence), and scenes under hypnosis, and men bursting into flame, and action sequences that are visceral in their shock value. I thought the movie careened out of control pretty early, and its nihilism wasn’t redeemed by an epilogue that assured us that this possessed policeman was, at moments, friendly and helpful. In this case, the storytelling innovations generated some confusion about exactly how the hero’s breakdown infused what was happening around him.

More consistent, largely because it didn’t try for the subjectivity of Lam’s film, was the Chinese cop movie Black Coal, Thin Ice. My friend Mike Walsh of Australia pointed out that the mainland cinema’s bleak realism seems to be starting to blend with traditional genre material. Director Diao Yinan explained, “My aim was not only to investigate a mystery and find out the truth about the people involved, but also to create a true representation of our new reality.” The opening crosscuts the grubby detail of bloody parcels churning through coal conveyors with a couple entwined in a final copulation before breaking off their relationship.

The mystery revolves around body parts that are showing up in coal shipments around one region. After a startling shootout in a hairdressing salon, the case remains unsolved for several years. The surviving detective, a shabby drunk, returns to track down the culprit, but in the meantime he runs into a frosty femme fatale. “He killed,” she says, “every man who loved me.” Needless to say, the detective falls for her too, especially after ice-skating with her. Diao’s film reminds us that you can create a neo-noir in two ways: By taking a mystery and dirtying it up, or taking concrete reality and probing the mysteries lurking in it.

There were even two Westerns. Another mainland movie, No Man’s Land, was unexpectedly savage coming from the director of the super-slick satires Crazy Stone (2006) and Crazy Racer (2009). Now Ning Hao has given us a bleakly farcical, Road-Warrior account of life on the Chinese prairie.

A wealthy lawyer brought out to the wasteland to negotiate a criminal case becomes embroiled in primal passions involving men with very large guns, very large trucks, impassive faces, and almost no sense of humor. It’s a black comedy of escalating payback (involving spitting and pissing), and it exudes sheer masculine nastiness. Completed four years ago [5], it found release only after extensive reshoots demanded by censors. Yet even in its milder state it remains true to the spirit of Sergio Leone’s jaunty grimness, bleached in umber sand and light.

Itching to see a Kurdish feminist political Western? You’ll find Hiner Saleem’s My Sweet Pepperland welcome. A tough policeman (= sheriff) is dispatched to a remote village in Kurdistan to keep order (= clean up the town). A young teacher (= schoolmarm) leaves her oppressive family to teach there as well. A warlord (= town boss) and his minions (= paid killers) have terrorized the locals, while marauding female guerillas (= outlaws) bring their fight into town.

These time-honored conventions shape a story of stubborn courage taking on complacent viciousness. In key scenes, our sheriff faces down big, hairy, scary killers.

USA frontier conventions, it turns out, work pretty well in a Muslim society too. The Hollywood Western’s continued embodiment of American values transfers easily to the former Iraq. “Our weapons are our honor,” the chief thug says, in a line that resonates through our history right up to now. Yet things we take for granted bring modern change to the wasteland. The sheriff assigns himself to the village in order to escape an arranged marriage, as the woman he finds there has done. She is vilified by both the locals and her male relatives, who would prefer death (hers) to dishonor (theirs). In the process, both he and she become heroic in a righteous, old-fashioned way.

A killer proposes a compromise while sneakily drawing his pistol. The cop shoots him and remarks: “I don’t do compromise.” Neither does My Sweet Pepperland.

Gangs of New York, and elsewhere

The Dreadnaught (1966).

From March to May, the Hong Kong Film Archive has been running a series, “Ways of the Underworld: Hong Kong Gangster Film as Genre.” It’s packed with classics (The Teahouse, To Be No. 1, City on Fire, Infernal Affairs) as well as several rarities (Absolute Monarch, Bald-Headed Betty, Lonely 15). I managed to catch three titles, all previously unknown to me.

The Dreadnaught (1966) has a familiar premise. Two orphan boys indulge in petty theft after the war. One, Chow, is caught but gets adopted by a policeman. He turns out a solid young citizen. Lee, the boy who escapes, grows up to be a triad. When the two re-meet, Lee is attracted to Chow’s stepsister. Some years later, Chow is now a cop and vows to smash Lee’s gang. After a struggle with his conscience, Lee agrees to help.

The film’s main attraction is the shamelessly flashy performance of Patrick Tse Yin. Tse would make his fame in the following year in Lung Kong’s Story of a Discharged Prisoner, famous as a primary source for A Better Tomorrow. With his sidelong smile, his endlessly waving cigarette, and the dark glasses he wears at all times, Tse in The Dreadnaught looks forward to Chow Yun-fat’s charismatic role as Mark in Woo’s masterpiece.

Another icon of the period is Alan Tang Kwong-wing. He played in over 100 films, mostly romances and triad dramas made in Taiwan. Westerners probably know him best as the producer of Wong Kar-wai’s first two features, As Tears Go By and Days of Being Wild. Wong had worked as a screenwriter for Tang. Onscreen, Tang had a suave, polished presence marked by his perfect coiffure; he was known as the Alain Delon of Hong Kong. His company, Wing-Scope, specialized in mob films during the late 1970s and early 1980s.

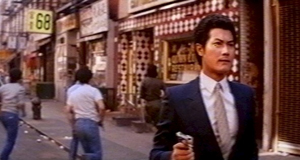

New York Chinatown (1982) shows Tang as a young hood whose ambitions to dominate the neighborhood are blocked by a rival gang. Eventually the police decide to let the two gangs decimate each other. This leads to an enjoyable, all-out showdown involving surprisingly heavy armaments. Shot quickly on location (passersby sometimes glance into the lens), the movie gives a rawer sense of street life than you get from most Hollywood films. There’s also a scene in which Tang, apparently attending Columbia part time, corrects a history professor lecturing on Western imperialism in China. Although the film circulates on cheap DVD in 1.33 format, it’s a widescreen production, and it was a pleasure to watch a fine 35mm print at the Archive.

The biggest revelation of the series for me was Tradition (1955), a Mandarin release. This is considered one of the earliest pure gangster films in local cinema. It’s a fascinating plot about a boy raised by a triad kingpin in the 1930s. When the godfather dies, the young Xiang is given power over the gang and the master’s household. Trying to be faithful to the old man’s principles, Xiang finds himself unable to control his master’s widow and daughter, who are led astray by the widow’s worldly, greedy sister. At the same time, Xiang must ally with other triads to smuggle aid to the forces fighting the invading Japanese. He is torn between devotion to tradition and the need to adapt to modern materialism and the impending world war.

[12]Tradition is redolent of film noir, not only in the sister-in-law’s fatal ways (she seduces the old master’s weak son) but also in the film’s flashback construction. Tracking back from a ticking clock, the movie begins with Xiang meeting the master’s daughter after his gang has been decimated in a shootout. The film skips back to Xiang’s childhood and takes us up through the main action before a final bloody confrontation with police and the corrupt family members. At the end, the camera tracks up to the clock, closing off the whole action.

[12]Tradition is redolent of film noir, not only in the sister-in-law’s fatal ways (she seduces the old master’s weak son) but also in the film’s flashback construction. Tracking back from a ticking clock, the movie begins with Xiang meeting the master’s daughter after his gang has been decimated in a shootout. The film skips back to Xiang’s childhood and takes us up through the main action before a final bloody confrontation with police and the corrupt family members. At the end, the camera tracks up to the clock, closing off the whole action.

Even more tightly buckled up are director Tang Huang’s obsessive hooks between scenes. A final line of dialogue is answered or echoed by the first line of the next scene; a closing door or character gesture links sequences in the manner of Lang’s M. Most daringly, when sister San starts to light a cigarette in one scene, we cut to her puffing on it in a tight close-up—a gesture that takes place in a new scene hours later. This and other admittedly gimmicky links look forward to Resnais’s elliptical matches on action in Muriel.

Fortunately for us, the Archive has published Always in the Dark: A Study of Hong Kong Gangster Films. Edited and partly written by Po Fung, it is an excellent collection of essays and interviews [13]. It is in Chinese, but it includes a CD-ROM version in English. It’s available from the Archive’s Publications office [14].

Behind the scenes at Milkyway

Johnnie To and a recalcitrant crane during the shooting of Romancing in Thin Air.

Sometimes a genre film becomes a prestige picture. This happened, in spades, with The Grandmaster [16]. If awards matter, Wong Kar-wai’s film has become the official best Asian film of 2013. I missed the Asian Film Awards in Macau (was watching early Farhadi films), but the event was a virtual sweep: seven top awards [17] for The Grandmaster, including Best Picture and Best Director. After I got back home, the Hong Kong Film Awards gave the picture a staggering twelve prizes [18], everything from Best Picture to Best Sound.

Unhappily, nothing in either contest went to the other outstanding Hong Kong film I saw last year, Johnnie To Kei-fung’s Drug War. It lacked the obvious ambitions and surface sheen of Wong’s film. Many probably took it as merely a solid, efficient genre picture. I believe it’s an innovative and subtle piece of storytelling, as I tried to show here [16].

Mr. To presses on, as prolific as usual. He has finished shooting a sequel to Don’t Go Breaking My Heart [19], a rom-com that found success in the Mainland, and he’s currently filming a more unusual project in Canton. More on that shortly.

During the festival only one recent To/Milkway film was screened, The Blind Detective (I wrote about that here [20]). But Ferris Lin, a young director from the Academy for Performing Arts, presented a very informative documentary feature on To and his Milkyway company. Boundless takes us behind the scenes on several productions, particularly Life without Principle [21], Romancing in Thin Air, and Drug War. It also incorporates interviews with To, his collaborators, and critics like Shu Kei.

Sitting at the monitor with his cigar, To may seem distant, but actually he is wholly engaged. We see him help push a crane out of the mud and shout commands to his staff. To confesses that he may scold too much, but the dedicated cooperation he gets confirms his demands. The team gives its all, as we learn when they explain the tension ruling the three days of rehearsal for the sequence-shot at the start of Breaking News [22]. For The Mission, made at the time of Milkyway’s biggest slump, the actors supplied their own cars and costumes.

To remains a complete professional who has perfected his craft, albeit in the Hong Kong tradition of “just do it.” He doesn’t rely on storyboards or even shot-lists, only outlines of the action, and he adjusts to the demands of the locations. The Mission had no script, but the entire story and shot layout were in his head. For Exiled, he didn’t even have that much and simply began thinking when he stepped onto the set each day. It’s hard to believe that precise shot design and sly dramatic undercurrents can emerge from such an apparently unplanned approach. In its recording of To’s unique creative process, Boundless provides a vivid portrait of one of the world’s finest contemporary directors.

To continues to challenge himself. He is currently trying something else again, shooting a musical wholly in the studio. Its source, the 2009 play [23] Design for Living, was written by and for the timeless Sylvia Chang Ai-chia. It won success in Hong Kong, Taiwan, and the Mainland. In the film Sylvia is joined by Chow Yun-fat, thus reuniting the stars of To’s 1989 breakout film All About Ah-Long. The project also indulges the director’s long-felt admiration for Jacques Demy. There is no 2014 film I’m looking forward to more keenly.

Special thanks to Shu Kei and Ferris Lin of the Hong Kong Academy for Performing Arts. Thanks as well to Li Cheuk-to, Roger Garcia, and Crystal Yau, as well as all the staff and interns of HKIFF, and to Winnie Fu of the Hong Kong Film Archive.

Journey to the West (Tsai Ming-liang, 2014).