Forgotten but not gone: more archival gems on DVD

Thursday | May 21, 2009 open printable version

open printable version

Kristin here-

We don’t make a practice of regularly reviewing DVDs here, but when a special release comes along that makes historically important, hard-to-see films available, we like to point it out. David spotlighted the new Criterion set of Shimizu Hiroshi films, and this week it’s Lotte Reiniger and Belgian experimental silents.

The lady with the flying scissors

Up until recently, the name Lotte Reiniger meant little to most people. Some were aware that she, rather than Walt Disney, had made the first animated feature film, The Adventures of Prince Achmed (1926). Some had been lucky enough to see a few of her shorts, created with a delicate silhouette technique using hinged, cut-out puppets. She had pioneered the approach in the late 1910s and continued to use it in much the same way up to her last films in the 1960s and 1970s.

Now, however, in another of the marvelous revelations that DVDs have made possible, we are in the process of having virtually all of Reiniger’s surviving work become available over a short stretch of time.

Early this year the British Film Institute released a two-disc set, “Lotte Reiniger: The Fairy Tale Films.” It concentrates on a series of thirteen films Reiniger and her husband Carl Koch made for television during an intensely productive period in 1954-55.

Two of these, Aladdin and the Magic Lamp and The Magic Horse, recycle footage from The Adventures of Prince Achmed, the elaborateness and delicacy of which stand out. Yet the rest of the series, though clearly made on a lower budget and remarkably quickly, are consistently excellent, with considerable detail of gesture and a great deal of wit (as in Thumbelina, right).

The rest of the program includes the 1922 Cinderella (left) which is Reiniger at her prime-though the detail of  one of the stepsisters slicing off part of her foot to make it fit in the tiny slipper may be a bit grim for some children. The Death-Feigning Chinaman (1928) is a fascinating item, a sequence cut from Prince Achmed and released as a free-standing tale. Reiniger made The Golden Goose (1944) in Berlin late in the war, as she cared for her ailing mother. It was not edited into a silent version until 1963, with a soundtrack being added for TV in 1988. It’s a real treasure that belies the grim circumstances of its making.

one of the stepsisters slicing off part of her foot to make it fit in the tiny slipper may be a bit grim for some children. The Death-Feigning Chinaman (1928) is a fascinating item, a sequence cut from Prince Achmed and released as a free-standing tale. Reiniger made The Golden Goose (1944) in Berlin late in the war, as she cared for her ailing mother. It was not edited into a silent version until 1963, with a soundtrack being added for TV in 1988. It’s a real treasure that belies the grim circumstances of its making.

The material following chronologically after the thirteen television episodes consists of three films. One, The Little Chimney Sweep, is the only disappointment in the program. It’s a revised, abridged version of a film from 1934, and the voiceover narration and truncated action downplay the subtle touches and charm that characterize all the other films. Fortunately the original survives and will be presented in the DVD program of the musical films.

The other two films are in color. I had never seen a color Reiniger film, but both are lovely, like old-fashioned children’s book-illustrations come to life. Jack and the Beanstalk (see image above) is the more polished of the two. Here black silhouette figures move amid brightly colored, stylized landscapes. It doesn’t sound like it should work, but it does. The Frog Prince is more what one would expect, with hinged colored puppets replacing the dark silhouettes. The result is highly engaging, though the lack of expression in the characters, which works so well for the dark silhouettes, might become too apparent in a film lasting more than a few minutes.

Wonderful though it is to have this big dose of Reiniger made available, I wish that the BFI had organized its presentation more helpfully. For a start, there’s no indication that this set is part of an ongoing series that will eventually make most of the filmmaker’s work available. No reference to that fact that the BFI already put out The Adventures of Prince Achmed in 2001, accompanied by an hour-long documentary, Lotte Reiniger: Homage to the Inventor of the Silhouette Film, directed by Katja Raganelli (which isn’t is also on the American disc released by Milestone). No announcement that a set of Reiniger’s music-based animated shorts is due out later this year or that the second set of GPO advertising shorts also due soon will include some Reiniger works (The Tocher and The H.P.O.), though brief references to that future release are buried in a couple of the program notes. (The two Reiniger films are already available on a British DVD called The GPO Story.) Only diligent trawling about the internet reveals such things. There’s a good summary of the situation in the DVD Times review of the fairy-tales set.

The program notes are fairly informative if you want plot synopses, but they provide virtually no historical context. There’s no general introduction to the program or the overall series, just a brief biographical note on Reiniger and notes on the individual films. I would have appreciated some information on the 1954 television series for which many of the films in the set were made.

Speaking of plot synopses, the notes for The Death-Feigning Chinaman miss a key narrative point. The title character, Ping Pong, gets drunk and starts eating a cooked fish that a young couple give him. The description continues, “Ping Pong eats a little of the fish, then tramples it in a drunken rage and falls down in a stupor.” This is a key moment, since his apparent death launches a snowballing accumulation of confusion, confession, and near execution. What actually happens is that Ping Pong chokes on a bone while eating the fish, and it paralyzes him. At the climax, an insect lands on his nose, he sneezes, the bone flies out of his mouth, and he emerges from his “death.”

Another instance of disorganization comes with a charming little color film, The Frog Prince, from 1961. It  was originally creates as an interlude in a stage pantomime, and on the disc it is presented silent. The program note comments, “No evidence of a soundtrack survives, and indeed sound seems unbefitting for a pantomime interlude. Although surprisingly, the aperture format of this mute positive print is 1:1.375 with an unused soundtrack area.” Yet the short documentary included in the set, The Art of Lotte Reiniger, includes The Frog Prince in its entirety, accompanied by lively and quite appropriate orchestral music. Given that Reiniger’s own production company made this film and she participated in its creation, it seems highly probable that the music used in the documentary was either the intended accompaniment for the film or at least considered suitable for it. A case of the right hand not knowing what the left is doing when this package was being put together, I guess.

was originally creates as an interlude in a stage pantomime, and on the disc it is presented silent. The program note comments, “No evidence of a soundtrack survives, and indeed sound seems unbefitting for a pantomime interlude. Although surprisingly, the aperture format of this mute positive print is 1:1.375 with an unused soundtrack area.” Yet the short documentary included in the set, The Art of Lotte Reiniger, includes The Frog Prince in its entirety, accompanied by lively and quite appropriate orchestral music. Given that Reiniger’s own production company made this film and she participated in its creation, it seems highly probable that the music used in the documentary was either the intended accompaniment for the film or at least considered suitable for it. A case of the right hand not knowing what the left is doing when this package was being put together, I guess.

The Art of Lotte Reiniger is a fascinating little film, despite the rocky sound quality of the surviving print. The filmmaker shows off her storyboards and puppets, but the really amazing thing is watching how quickly she cuts the silhouettes, freehand, out of black paper.

For those who read German and want as full a dose of Reiniger as possible, an 8-disc box is already available, including Prince Achmed, the fairy-tale and music shorts, and a two-disc set called “Dr. Dolittle & Archivschatze” (Dr. Dolittle and archive treasures).

Animation historian William Moritz provides a biographical note and filmography for Reiniger here. It or something like it would have been a helpful introduction to the DVD booklet.

“This is not a pipe,” the movie

As of February of this year, I have been visiting the Cinémathèque royale de Belgique/the Koninklijk Film Archief, or, unofficially, the Royal Film Archive of Belgium, for thirty years now. (David made his first visit there in 1982.) It has been a tremendous resource for us, and its staff, especially current archive director Gabrielle Claes, have invariably been generous and welcoming.

Being a government-supported institution in a bilingual country, the Archive renders all texts in French and Flemish, from the monthly screening schedules to the subtitles that sprawl across the bottoms of frames. Now, as part of a renovation of the screening venue and museum space, the Royal Film Archive has abandoned all that verbiage and officially renamed itself the Cinematek. That’s not a real word in any language, but it conveys more or less the same thing in French, Flemish, and English. I suspect that the epic subtitles will remain. For full details of the new facility and programming, go here.

Before the name change, the archive had started a DVD series awkwardly entitled “filmarchief dvd’s – les dvd de la cinémathèque.” These are collections of archival films mostly relating to Belgium, and a lot of them are documentaries. The series includes an excellent new two-disc set, “Avant-Garde 1927-1937.” (The archive also publishes modern films, mostly in Flemish.) It’s in fact a trilingual release, with the subtitle “Surréalisme et expérimentation dans la cinéma belge/Surealisme en experiment in de Belgische cinema/Surrealism and experiment in Belgian cinema.” The text of the detailed accompanying booklet is in all three languages, and the discs also offer options for subtitles in any of the three. The producers have taken great care with the music, commissioning Belgian musicians to compose and perform modernist chamber-orchestra scores. These vary considerably, effectively matching the tone and style of each film. The design of the packaging is practical and sturdy: it’s a small hard-cover book with the pages containing the text and the discs fastened onto the endpages.

Belgian silent experimental cinema might sound a bit obscure, but recall that the country had a pretty prominent role in the Surrealist movement, mostly famously with painter René Magritte. Categorizing all the films on these discs as Surrealist is a bit of a stretch. Some fit that designation, but others are more like city symphonies and political documentaries, and a couple defy definition. But if the label attracts more attention, all the better. Henri Storck and Charles Dekeukeleire, the filmmakers whose works dominate the set, are major filmmakers, and the two shorts that fill out the discs are of historical interest–and genuinely Surrealist.

Storck has long been better remembered than Dekeukeleire. He helped form the national film archive in the late 1930s, and he went from experimental cinema in the 1920s to become a prominent documentarist for the rest of his career. His collaboration with Joris Ivens, Misère au Borinage (1933), is a classic in the genre.

Disc One

Storck dominates the first disc with four titles. his Images d’Ostende (1929) is a quiet study of the seaside resort town where the filmmaker was born. It’s a lovely debut, revealing his eye for composition and  feeling for nature. There’s nothing Surrealist about it. It’s closer to some of the more familiar lyrical studies of the era, like Ivens’ Rain. The accompanying music is modernist with a 1920s feel; a soprano voice weaves subtly through the instrumentation.

feeling for nature. There’s nothing Surrealist about it. It’s closer to some of the more familiar lyrical studies of the era, like Ivens’ Rain. The accompanying music is modernist with a 1920s feel; a soprano voice weaves subtly through the instrumentation.

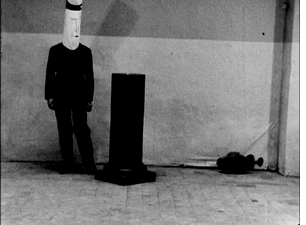

The second film, Pour vos beaux yeux (1929), is a fiction film and definitely Surrealist. The story is minimal. A man finds a false eye lying on the ground. He visits a prosthetics shop, makes plans involving maps, and contemplates the eye on a pedestal while wearing a peculiar cylindrical mask (left). Eventually he wraps the eye in a box and attempts to mail the package.

The program notes claim that Storck could not have seen Un chien andalou when he made Pour vos beaux  yeux. That’s difficult to believe, given that the film seems almost to be an elaborate riff on that film’s eyeball-slitting shot. There are definite references to Ballet mécanique, and the seashells that line the desk where the protagonist wraps the package recall Germaine Dullac’s La coquille et le clergyman.

yeux. That’s difficult to believe, given that the film seems almost to be an elaborate riff on that film’s eyeball-slitting shot. There are definite references to Ballet mécanique, and the seashells that line the desk where the protagonist wraps the package recall Germaine Dullac’s La coquille et le clergyman.

Storck had obviously seen Eisenstein films as well, including October. Histoire du soldat inconnu (1932) is made up of footage from 1928, when an anti-war treaty had been signed. The filmmaker uses intellectual montage to make the point that militarism and the institutions that support it are clearly going to make mincemeat of the treaty’s ideals. The approach is pretty simple, juxtaposing marching soldiers with religious processions. At that point in film history, it was probably still a pretty novel idea that one could cut from a pompous politician speaking to a small dog yapping. By now it looks pretty heavy-handed.

Indeed, the next film in the program, Sur les bords de la caméra (also 1932, also incorporating found footage from 1928) uses the same technique with more restraint. It reminded me a little of Bruce Conner’s A Movie, where odd juxtapositions gradually come to seem more sinister and finally disastrous. Scenes of groups exercising, religious processions, shots in traffic and in prison, all add up to a suggestion that a whole population is voluntarily doing regimented things controlled by the police and other authorities.

On my first visit to the Royal Film Archive back in 1979, one of the titles on my to-see list was Impatience, an experimental film by Charles Dekeukeleire. I had seen a reference to it in the British-Swiss journal of film art, Close-Up. Jacques Ledoux, director of the archive, was delighted that anyone should want to see a film by this nearly forgotten director. He urged me to see Deukeukeleire’s other experimental films, all made in the 1920s and early 1930s before he, too, moved into documentary work.

I saw Combate de boxe (1927), made when Dekeukeleire was only 22. Combining negative and positive footage, hand-held camera, rapid montage, masks–pretty much all the devices of the European avant-garde of the day–he strove to give the subjective impressions of the two combatants in the ring. That’s the first of four Dekeukeleire films in this set. It’s an impressive film by a very young, talented man–but not one that suggests the highly original artist that he would soon become.

The last film on disc one skips forward to 1932, when Dekeukeleire made Visions de Lourdes. Beginning with conventionally beautiful mountain vistas, the film slowly moves toward the area around the sacred grotto and finally to shots within the grotto itself. There are shots of shop-windows full of Lourdes souvenirs (including candy made with holy water from the shrine), but these come in fairly late, avoiding a blatant focus on the commercialization of the site and the notion that those hoping to be healed of illness and deformity are being exploited.

Clearly Dekeukeleire has a more original sense of composition than does Storck. There is a motif of old women selling candles that the filmmaker turns into a series of shots that look like something out of Eisenstein’s Mexican footage–which of course Dekeukeleire could not have seen. (See the image at the bottom, which has enough gap framing to impress even David.) The film is critical of the church, but subtly so–and perhaps mainly because we’ve been cued to take it that way, especially in this case by the dissonant music. I wonder if, in a different context and with a cheerier soundtrack, some of the devout might actually take it as a serious tribute to the healing powers of the saint. They would be mistaken, I think, but the film is understated enough that I think it’s possible.

Disc Two

Dekeukeleire’s two masterpieces, however, were made between these Combat de boxe and Visions de Lourdes. Impatience (1928) is an abstract film that hints maddeningly at a possible narrative situation that never develops. Instead, shots of  four “personnages,” a woman, a motorcycle, a mountainous landscape, and three abstract blocks are edited together. None of these elements is every seen in a shot with any of the others. Rapid montage, vertiginous views against blank backgrounds, upside-down framings, and ruthless, unvarying stretches of repetition make this one of the most challenging, opaque films of its era.

four “personnages,” a woman, a motorcycle, a mountainous landscape, and three abstract blocks are edited together. None of these elements is every seen in a shot with any of the others. Rapid montage, vertiginous views against blank backgrounds, upside-down framings, and ruthless, unvarying stretches of repetition make this one of the most challenging, opaque films of its era.

Perhaps in the wake of post-World War II experimental cinema, where spectator frustration and the denial of conventional beauty and entertainment are often part of a film’s intent (Michael Snow’s Wavelength comes to mind), we are better equipped to understand a film like Impatience, which in its day baffled most reviewers and audiences. Indeed, now Impatience is widely considered to be the best of Dekeukeleire’s avant-garde films.

I think that’s partly because one can at least classify it as an abstract film. For me, his next and longest experimental work, Histoire de detéctive (1929), is even more daring. It purports to present a story in which a  detective named T is hired by Mrs. Jonathan to investigate why her husband has been behaving in a peculiar fashion. T uses a movie camera to record Mr. Jonathan’s actions, and what we see purports to be the results. But, as a title points out, sometimes conditions made T’s filming impossible. What we see are scraps of scenes rather than coherent, continuous footage. The narrative deliberately depends extensively on lengthy intertitles and inserted documents, while the images suggest little in the way of narrative–as when repeated shots show Jonathan lingering on a bridge in the tourist town of Bruges while the intertitles list all the famous sights that he didn’t see (left).

detective named T is hired by Mrs. Jonathan to investigate why her husband has been behaving in a peculiar fashion. T uses a movie camera to record Mr. Jonathan’s actions, and what we see purports to be the results. But, as a title points out, sometimes conditions made T’s filming impossible. What we see are scraps of scenes rather than coherent, continuous footage. The narrative deliberately depends extensively on lengthy intertitles and inserted documents, while the images suggest little in the way of narrative–as when repeated shots show Jonathan lingering on a bridge in the tourist town of Bruges while the intertitles list all the famous sights that he didn’t see (left).

Histoire de détective flew in the face of all contemporary assumptions about the “cinematic” lying in images with as few intertitles as possible. It was audacious in ways that annoyed critics, and its considerable humor went right past most of them. Dekeukeleire apparently realized that his distinctive brand of experimentation had virtually no audience, and he turned to documentaries.

For some reason this program does not include his Witte Vlam (1930), a short Vertovian drama about a protest march broken up by police. It’s not Surrealistic, but no less so than some of the other films included here.

The two final films in the set are by directors who only made one film each. Both refer to Louis Feuillade’s  work, suggesting that his serials, though a decade old and more by the end of the 1920s, retained their hold on the Surrealist imagination.

work, suggesting that his serials, though a decade old and more by the end of the 1920s, retained their hold on the Surrealist imagination.

Henri d’Urself’s La perle (1929), is quite self-consciously a Surrealist work about a young man who keeps trying to buy and deliver a pearl necklace to his beloved, only to give it away to a lovely thief who tries to steal it from his hotel room. The thief is only one of several women lurking in the hotel corridors, all dressed in skin-tight body suits that recalls those worn by Musidora in her immortal role as villainess Irma Vep in Les Vampyrs. In true Surrealist fashion, although the hero enters a jewelry shop in a bustling street of a large city, he exits the building directly into country scene (right).

The last and latest of the films in the set is Ernst Moerman’s Monsieur Fantômas (1937), an intermittently  amusing homage to the super-villain of Feuillade’s 1913 serial. Traveling the globe in search of his true love, Fantômas (left, imitating his famous pose from the film’s posters) apparently commits a murder and is investigated by Juve, Feuillade’s clever but perpetually thwarted opponent. Filming on virtually no budget, Moerman set his action mainly on a beach and in an old cloister, thus allowing him to add some of the anti-religious touches so beloved of the Surrealists.

amusing homage to the super-villain of Feuillade’s 1913 serial. Traveling the globe in search of his true love, Fantômas (left, imitating his famous pose from the film’s posters) apparently commits a murder and is investigated by Juve, Feuillade’s clever but perpetually thwarted opponent. Filming on virtually no budget, Moerman set his action mainly on a beach and in an old cloister, thus allowing him to add some of the anti-religious touches so beloved of the Surrealists.

A bit of six-degrees-of-separation trivia: Fantômas is played by Jean Michel, the future father of French actor-singer Johnny Hallyday, who stars in Vengeance, the Hong Kong film by David’s friend Johnnie To that’s playing at Cannes this year.

The Belgian avant-garde cinema of this era is not a little backwater that merits a quick look only by specialists. Storck’s and particularly Dekeukeleire’s works are as sophisticated and challenging as almost anything that was going on in experimental filmmaking of the era, though the latter’s films were so idiosyncratic that they had no noticeable influence.

Back in 1979, when I learned about Dekeukeleire, I was so impressed that I sought to bring him some attention. I wrote an article, “(Re)Discovering Charles Dekeukeleire.” As the title suggests, Dekeukeleire hadn’t fallen into obscurity but had languished there from the beginning. Unfairly so, as I argued in the article, which was published in the Fall/Winter 1980-81 issue of the Millennium Film Journal. With this new DVD set making his and his colleagues work more accessible, I am inspired to revive my old article, which helps explain, I hope, some of what seems to me so original and daring about his early films, particularly Impatience and Histoire de detétective. The piece was written in the pre-digital age, and scanned .pdfs would probably be scarcely readable. So I plan to retype the thing and post it in the articles section of David’s website as soon as possible. [June 4: Done! Now available here.]

I hope that now devotees of animation and experimental cinema will seek out both these DVD sets. The Belgian one is in the PAL format, but without region coding. The Reiniger is also PAL, region 2 coding.

[May 23: Thanks to Harvey Deneroff for a correction concerning the American DVD of Prince Achmed.]