How do you get people to believe that if you can’t get the press to make an honest assessment of it? You tell a story. “When it came down to a choice between my very life and my country, I chose my country.” That’s why the story’s important. Just as Obama’s story is important to him. I don’t gainsay it. You know, tell your story! —John McCain staff member and co-author Mark Salter [3]

There was a mismatch between the way he was behaving and the narrative the press had bought into. It made reporters wonder, “Have we been had?”–Professor Marion Just, Wellesley, on John McCain [4]

This political bullshit about narratives.–Peggy Noonan, Republican columnist [5]

I’m David Bordwell and I approved this message.

A long time ago a student complained to me that we film academics were foisting upon them words that no professional filmmakers used. The student’s example was “genre.” Today of course filmmakers use the term all the time. Sometimes you hear “classical filmmaking,” and Variety [6] tells us [6] that Henry Jenkins [7]’ label “transmedia” is starting to break through:

Famed s/f writer Larry Niven is working with “transmedia” (today’s new buzzword) production company Alchemic Productions to create a new game property called “Free Fall.”

More broadly, the terminology of Big Theory in the humanities has trickled into journalism and politics. For some time now “deconstruction” has been peppering mass-market discourse. Granted, it’s not employed in the way Derrida and his acolytes would like. It seems to mean a blend of “construction” and “destruction,” which can entail “analysis” or even just “pulling something apart.”

Deconstruct Black Ink [8]: Your children can use chromatography to deconstruct black ink and find out what color the ink really is.

Scientists Deconstruct Clownfish Chatter [9]

U. of Kansas Looks to Deconstruct Its School of Fine Arts [10]

This election season has shown me that even the idea of the Other, considerably divorced from its use by Jacques “The Lack” Lacan, can show up. Nicholas Kristof claims [11] that John McCain’s efforts to suggest that Barack Obama isn’t “sufficiently Christian” are an effort to “otherize” him.

But I think the term that has gotten the most play is “narrative.”

Discovering narrative

During my days as an undergraduate in literary studies and as a grad student in film studies, between 1965 and 1973, you scarcely ever heard the word. It doesn’t appear in the index of Wellek and Warren’s Theory of Literature (3rd ed., 1956) or Wimsatt and Brooks’ Literary Criticism: A Short History (1957) or Northrop Frye’s Anatomy of Criticism (1957). Story, tale, plot, dramatic structure: these words were common, but not “narrative”.

In American academia, the term began to gain currency with Robert Scholes and Robert Kellogg’s The Nature of Narrative (1966). The authors identify narrative with a broad literary tradition, embodied not only in the novel and short story but also in oral storytelling. And the definition is clearly language-based, in pointed contrast with drama.

By narrative we mean all those literary works which are distinguished by two characteristics: the presence of a story and a story-teller. A drama is a story without a story-teller; in it characters act our directly what Aristotle called an “imitation” of such action as we find in life. (4)

The Nature of Narrative was published the same year that Roland Barthes, in a special issue of the French journal Communications, published his essay “Introduction to the Structural Analysis of Narratives.” (1) His conception of narratives (récits) is far more generous than that of Scholes and Kellogg.

Narrative is first and foremost a prodigious variety of genres, themselves distributed amongst different substances—as though any material were fit to receive man’s stories. Able to be carried by articulated language, spoken or written, fixed or moving images, gestures, and the ordered mixture of all these substances, narrative is present in myth, legend, fable, tale, novella, epic, history, tragedy, drama, comedy, mime, painting (think of Carpaccio’s Saint Ursula), stained glass windows, cinema, comics, news item, conversation. (79)

Barthes’ essay, along with other Structuralist studies, initiated the academic field of “narratology,” the systematic study of storytelling as it is manifested in many media. From the 1970s to the present, this became a vast, varied, and exciting area of inquiry.

The questions are fascinating.

*What is a story? How does it differ from other things, such as a description or an abstract image? Are jokes narratives? Are dreams? Are riddles? Is the concept so broad that anything can be treated as a story?

*Why do stories engage us? What do we need to know, or do, to understand a story? What powers enable us to create stories? Are story-making and story comprehension distinctively human activities?

*Do stories rendered in language differ from those rendered in other media? Is the ability to make or follow stories dependent on our knowing language, even if the story is presented without words (as, say, a silent film)?

*How do narratives imply or suggest or symbolize broader meanings than the bare events they recount? What enables a narrative to stand for more than it seems to say?

*What patterns of narrative construction do we find in different traditions, periods, times, and places? How might they bear the traces of social and political views? How might they express varying conceptions of the world?

In retrospect, we can see that Aristotle, nineteenth-century theorists of the drama, and theorists like Walter Benjamin, Georges Polti, R. S. Crane, and Northrop Frye did reflect on the phenomenon as narratologists were beginning to conceive it. But very few thinkers had asked these particular questions, in quite the way that Barthes and other Structuralists had.

The questions may seem impossibly abstract or broad, but they get more manageable if we look at particular cases. Take film. We all assume that Hollywood movies belong to a storytelling tradition, one that some people consider formulaic. But if Hollywood movies are formulaic, they must adhere to conventions—conventions we might not find, say, in Homer’s epics or Ibsen’s dramas or Neorealist films. What are those narrative conventions? Where did they come from? How do they fit together? What might be their effects on viewers’ beliefs and experiences?

Studying the narrative conventions of various filmmaking traditions has kept Kristin and me busy for many years. We explained some rudiments of narrative theory in the first edition of Film Art (1979); I think that this was the first time an introductory textbook put the area on the film studies agenda. In the 1980s we wrote The Classical Hollywood Cinema and Narration in the Fiction Film; in the 1990s Kristin wrote Storytelling in the New Hollywood; in the 2000s I wrote The Way Hollywood Tells It and Poetics of Cinema. Most recently we composed some items on this website (here [12] and here [13] and here [14]).

Now, after a thirty-year pageant of academic theories and analyses, we find that the term has trickled down, so to speak, to bare-knuckle politics. It turns out that the current Presidential election in the U. S. is all about “narratives [15].” The candidates have them, as do the campaigns. And those narratives are served up in newspaper accounts that are also narratives. How the word gained its new status is a question for another time. For now, we have plenty of tales to occupy the narratologist.

Two quick caveats

Narrative doesn’t equal fiction. Most narratologists have followed Barthes in treating factual accounts, like newspaper stories and conversations, as narratives. Sometimes a filmmaker will say, “I make documentaries, not narratives,” but documentaries can be, and often are, narrative in form. So too are some avant-garde films, such as Meshes of the Afternoon and Tribulation 99. One of the reasons that we study narrative is that it’s a very widespread phenomenon.

This is not to say that the fact/ fiction distinction doesn’t matter. We react differently to narratives purporting to be fictional and ones claiming to be factual. And studying narrative doesn’t commit us to saying that all narratives are fictional (because they’re constructed, or because they’re selective, or whatever). History books and newspaper reports can be more or less faithful to what really happened. And sometimes fact seems more narratively coherent than fiction. If you wrote a novel about an idealistic presidential candidate born in a town called Hope, you’d be accused of heavy-handed symbolism; but tell that to Bill Clinton.

Narrative is a type of representation. What happens to you today isn’t a narrative until you tell somebody about it, or write it up in your diary, or at least sort it out as a story in your mind. A narrative, as the name implies, is a string of events that is narrated—represented in some form. In this sense, the Presidential campaign isn’t a narrative in and of itself. It becomes a narrative when people represent it: select events, omit others, perhaps invent or imagine still others, and present them in words, pictures, music, or some other medium.

This idea of presenting a chain of causally connected events, enacted by agents and unfolding in time, is what we characteristically mean by storytelling. You can find a more abstract definition of narrative in Film Art and other things Kristin and I have written, but this will suffice for now.

The plots thicken

Clearly the presidential candidates have come to believe that what seizes the public aren’t just policy views and promises. Now the campaigns want to tell stories in which the candidates are the protagonists. The life of Barack Obama, or Joe Biden, or Sarah Palin is said to be a story (usually “an American story”). According to Robert Draper’s influential recent article, John McCain’s campaign has deliberately set out a series of “narratives”: McCain endures suffering in Hanoi as a POW; he enters politics and fights for reform in government. Mark Salter, McCain’s staff member and coauthor, has the responsibility of stitching incidents of the Senator’s career into what he calls the “metanarrative” of McCain’s life [3]—rather as George Lucas presides over the Bible of the Star Wars universe.

The campaigns’ efforts at representing narratives don’t just amount to giving us backstory about the protagonists. Things get tricky when they try to present the ongoing campaign as itself a narrative. This involves planning a smooth cascade of events, such as during the party convention, when the suspense builds toward the climax of nomination. The problem of course is that events outside the candidates’ control can force changes in the story line. During the recent financial meltdown, McCain’s campaign would have preferred to create a dialogue about national security, and Obama’s campaign was prepared to talk about the war and the squeeze on the middle class. Instead, each had to respond to swiftly changing events and rewrite the script every day.

Why is the McCain campaign flagging? Contrary to Salter’s intentions, many believe that it never found “a compelling story”—that is, a way to integrate all the events hurled at their ideal scenario. Obama’s story was simpler: he could simply point to each new catastrophe as caused by Republican rule.

Sometimes the mass media replay the narratives concocted by the campaign, but sometimes they offer counter-narratives. A Rolling Stone article [16] sought to replace the official McCain “metanarrative” by adding incidents, characters, and causes that add up to a far more damaging story. More broadly, a common account portrays the campaigns as a study in contrasts: Obama’s enterprise ran steadily according to the well-planned strategy of pursuing votes in nearly every state, while McCain’s campaign was more tactical and reactive, taking red states for granted. And as in any good narrative, the actions are treated as reflecting the traits of the two characters. Obama is seen to be calm and measured, so his campaign runs smoothly; McCain appears splenetic and tightly wound, so his campaign is spasmodic. Character and action are believed to mesh. (More on character traits shortly.)

Once these narrative arcs are in place, they become hard to dislodge. As I write this, unnamed handlers in the McCain campaign are blaming one another and Sarah Palin, and this new string of incidents only seems to confirm the scenario of a rudderless, probably doomed, enterprise. Other observers, and historians in future years may embellish, revise, or reject the mainstream account. My point is that we’ve watched a standard story emerge as a full-bodied narrative, or rather a cluster of them—the way that a folktale or myth presents different variants of emphasis and point of view. Still, each one of the variants is a narrative—a representation of a string of events, enacted by agents and bound together through chronology and causal connections.

What’s your story?

I long ago learned to distrust my childhood and the stories that shaped it. It was only many years later, after I had sat at my father’s grave and spoken to him through Africa’s red soil, that I could circle back and evaluate these early stories for myself. Or, more accurately, it was only then that I understood that I had spent much of my life trying to rewrite these stories, plugging up holes in the narrative, accommodating unwelcome details, projecting individual choices against the blind sweep of history, all in the hope of extracting some granite slab of truth upon which my unborn children can firmly stand.

Barack Obama, Dreams from My Father, xv-xvi

Each of the two top presidential candidates has signed an autobiography that functions, in today’s story-hungry ecosystem, as a bid to control his narrative. In 1995, Obama published Dreams from My Father: A Story of Race and Inheritance; four years later McCain produced Faith of My Fathers: A Family Memoir. In what follows, I’ll refer to the latter as McCain’s book, though apparently coauthor Mark Salter is responsible [19] for both a lot of the research and the actual prose of the result.

Like Steven Spielberg and Martin Scorsese, Obama and McCain are deeply concerned with fathers and how they shape sons. Both books portray three generations of men: the author, his father, and his grandfather. The concern for the father’s role is enacted in the overall design of each narrative.

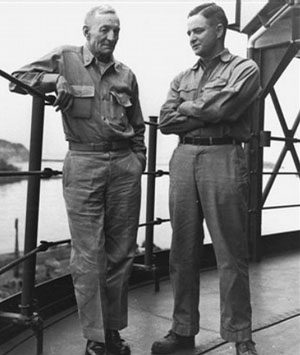

McCain’s book is more straightforwardly chronological, and it proceeds in three layers. After an emblematic moment when his father and grandfather met at the end of World War II (more on this below), the narrative starts with a brief biography of the elder, McCain senior, who served as an admiral under William Halsey during World War II. There follows a somewhat longer account of McCain junior, who also won the rank of Admiral and who commanded naval operations during the Vietnam war. Woven into these accounts are vignettes of the youngest McCain’s reactions to these two awe-inspiring warriors.

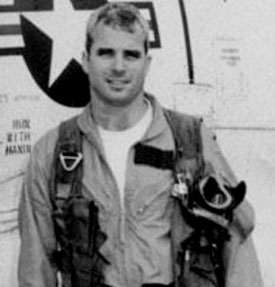

The bulk of the book presents his own life, rendered chronologically. He swiftly runs through a “misspent youth” of impulsive rebellion and reluctance to kowtow to authority. McCain expresses gratitude for the family heritage—a sense of duty and, above all, honor—that informed his life. But he did not fully understand the weight of these traditions, he tells us, until he was taken prisoner by the North Vietnamese and was held as a POW for over five years. There, under severe torture and despite the greatest resistance he could muster, he signed a false confession. It was a betrayal not only of his country, but of a family tradition.

They were the worst two weeks of my life. I couldn’t rationalize away my confession. I was ashamed. I felt faithless, and couldn’t control my despair. I shook, as if my disgrace were a fever. I kept imagining that they would release my confession to embarrass my father. All my pride was lost, and I doubted I would ever stand up to any man again. Nothing could save me. No one would ever look upon me again with anything but pity or contempt. . . . The Vietnamese had broken the prisoner they called the “Crown Prince,” and I knew they had done it to hurt the man they believed to be a king. (244-245)

The rest of the narrative tells of redemption. Months of poor medical care, mind-numbing routine, solitary confinement, and spasms of torture had made McCain vulnerable. But in living with other prisoners, McCain discovers that loyalty to country merged with loyalty to comrades and to God. Honor and duty are bound up with faith.

I was no longer the boy to whom liberty meant simply that I could do as I pleased, and who, in my vanity, used my freedom to polish my image as an I-don’t-give-a-damn nonconformist. . . . In prison, where my cherished independence was mocked and assaulted, I found my self-respect in a shared fidelity to my country. All honor comes with obligations. I and the men with whom I served had accepted ours, and we were grateful for the privilege. (255)

By the time he is released, McCain—now living with other prisoners—can help create the bonds that make them resist, and occasionally subvert, their captors’ plans. (Among other things, he enlivens their nightly meetings with long recitations of the plots of movies he has seen.) And he refuses to be released out of the sequence of his capture. At the end, on the verge of freedom, the boyish McCain reemerges, offering some insolent quips to Vietnamese officers. He returns home, not to his father—that conventional scene is oddly absent—but to a greater sense of his responsibility.

McCain has spoken of Viva Zapata! as his favorite film, but in reading the book I couldn’t escape the feeling that it traces, in a less light-hearted tenor than Ford’s film does, the way in which Ensign Pulver becomes Mr. Roberts.

The narrative arc of Dreams from My Father is far less linear in its plot. At bottom, it is a conventional autobiography, telling how a boy born in Hawaii to an American mother and a Kenyan father, wound up going to law school. Unlike McCain, who grew up knowing about the triumphant careers of his father and grandfather, Obama never really knew his father. His parents divorced when he was two, and he saw his father only once, when he was ten. His mother, and then his grandparents, were his family. The narrative is, like McCain’s, presented in three parts, but these correspond to three stages of the protagonist’s life: an early phase of childhood, high school, and college; a period of young manhood spent in Chicago, organizing community groups for social improvement; and a trip to Kenya before entering Harvard.

If McCain’s book is an adventure tale, Obama’s is a detective story. The through-line, as screenwriters might say, is Obama’s search for his identity as a African American. If McCain’s plot is driven by honor and duty, Obama’s depends on race and social responsibility. McCain steers by a fixed star, and is shamed when he goes off course. Obama is scanning the heavens for some stable pole that will give him a sense of who he is.

In Chicago, he is confronted with the poverty and fragmentation of the black community. Some failures and moderate successes in community organizing give his young life a degree of purpose. He learns from Harold Washington and various preachers, surrogate father figures, that there are larger forces working to tear apart the fragile unity citizens might achieve. The chief danger is losing hope. Attending a service by Jeremiah Wright and hearing talk of “the audacity of hope,” Obama has a conversion:

If a part of me continued to feel that this Sunday communion sometimes simplified our condition, that it could sometimes disguise or suppress the very real conflicts among us and would fulfill its promise only through action, I also felt for the first time how that spirit carried within it, nascent, incomplete, the possibility of moving beyond our narrow dreams. (294)

But still his own history feels incomplete, and he sets out to complete it by visiting his father’s tangled family in Kenya. He finds he has many brothers, sisters, aunts, and uncles. He witnesses deep divisions in a squabble over his father’s estate, and he comes to realize how family bonds can be both liberating and stifling. As he explores, he learns more about his father and, eventually, his grandfather.

McCain gives encapsulated judgments of his father and grandfather, while Obama keeps offering partial portraits, images slipping in and out of focus. His father was a noble man, much respected till his death; no, he fell into drunken lassitude; no, even in his decline he was generous and loyal to his friends. Eventually, talking with his grandmother, Obama learns of the history of his father’s family. As in a detective story, the book’s climax is a recitation of what the protagonist had never known, the hidden causes of why his mother and father divorced—and the revelation of a secret his mother and her parents had always kept from him. Like McCain, Obama finds himself, but not through living up to an external code of conduct. By an act of sympathetic imagination, Obama grasps how he continues to live, in his own register, the problems and promise embodied in a man who had abandoned him two decades earlier.

Obama’s tale is more complex than McCain’s, but each one reflects the image of the protagonist. McCain lives in a world of clear-cut demands, called the Code, and so any problem comes from failing to meet the obligations of duty. Obama’s world is hazy and uncertain; there is no Code. How should a man like him, with his heritage, find a way to live with dignity?

Telling details

The differences in the overall narrative progression get embodied in differences at the level of texture, or narration—the concrete way each story is told, moment by moment. Consider the opening of Faith of My Fathers:

I have a picture I prize of my grandfather and father, John Sidney McCain Senor and Junior, taken on the bridge of a submarine tender, the USS Proteus, in Tokyo Bay a few hours after the war had ended. They had just finished meeting privately in one of the ship’s small staterooms and were about to depart for separate destinations. They would never see each other again.

Despite the weariness that lined their faces, you can see they were relieved to be in each other’s company again. My grandfather loved his children. And my father admired my grandfather above all others. My mother, to whom my father was devoted, had once asked him if he loved his father more than he loved her. He replied simply, “Yes, I do.”

And here are the opening lines of Obama’s memoir:

A few months after my twenty-first birthday, a stranger called to give me the news. I was living in New York at the time, on Ninety-fourth between Second and First, part of that unnamed, shifting border between East Harlem and the rest of Manhattan. It was an uninviting block, treeless and barren, lined with soot-colored walk-ups that cast heavy shadows for most of the day. The apartment was small, with slanting floors and irregular heat and a buzzer downstairs that didn’t work, so that visitors had to call ahead from a pay phone at the corner gas station, where a black Doberman the size of a wolf paced through the night in vigilant patrol, its jaws clamped around an empty beer bottle.

A card-carrying narratologist could squeeze a whole article out of these two openings, but just notice how well designed each is. Both grab the reader: Why would McCain’s father and grandfather never meet again? What was “the news” headed for Obama? The short, crisp sentences of the McCain extract—few adjectives and adverbs, no description except for the lines on the men’s faces—set the pace for what we’ll get later. McCain (via Salter) tells his tale in brief paragraphs and unvarnished prose, as laconic as the talk of the seamen he admires. The two opening scenes, that of father and son meeting on the bridge of the Proteus and the moment when McCain’s father tells his wife that he loves his father more than her, might have come from a John Ford film. The climactic “Yes, I do” even enacts that legendary Ford dictum that you shouldn’t let actors talk much.

Obama’s scene is more like a sequence from a 1970s urban movie, yielding washed-out imagery packed with scruffy detail. Everything suggests “dangerous neighborhood” and “black poverty,” but at no point does Obama use any of those words. Instead we get suggestions of grime and bleakness. As in many novels, the milieu comes to life through action: the broken buzzer initiates the routine of people calling ahead. By metonymy, the adjacent gas station reminds the narrator of the almost hallucinatory Doberman trotting through the night. And instead of telling us that drunkards left their beer bottles littering the streets, this paragraph suggests this sorry milieu obliquely by having the patrol dog clenching one in its jaws.

It might be tempting to say that McCain is deliberately avoiding literary grace notes, as befits a man identified with Straight Talk, while Obama is writing in a self-consciously novelistic way, like the elitist he is. Actually, no. Both are writing in literary ways, but using different techniques of narration.

Obama is adhering to Henry James’ admonition to “Dramatize, dramatize!” He tries to make every scene come alive for the reader through small details. He’s the sort of memoirist who not only gives you twenty-year-old conversations word for word, but adds all the gestures, vocal tones, and props.

“See there,” Marcus said. “Makes you embarrassed, don’t it—just being seen with a book like this. I’m telling you, man, this stuff will poison your mind.” He looked at his watch. “Damn, I’m late for class.” He leaned over and pecked Regina on the cheek. “Talk to this brother, will you? I think he can still be saved.”

Regina smiled and shook her head as we watched Marcus stride out the door. “Marcus is in one of his teaching moods, I see.” (103)

This sort of prose is movie-adaptation ready: You can see the scene. McCain doesn’t work at this level of concrete rendition, but his narration is no less carpentered. Consider this passage:

I didn’t think, “Gee, I’m hit—what now?” I reacted automatically the moment I took the hit and saw that my wing was gone. I radioed, “I’m hit,” reached up, and pulled the ejection seat handle.

I struck part of the airplane, breaking my left arm, my right arm in three places, and my right knee, and I was briefly knocked unconscious by the force of the ejection. Witnesses said my chute had barely opened before I plunged into the shallow water of Truc Bach Lake. I landed in the middle of the lake, in the middle of the city, in the middle of the day. An escape attempt would have been challenging. (189)

Things happen quickly here. The scene is over in seven sentences—no description of what the blackout felt like, no sense of imminent death. Point of view switches with equal speed. McCain is fully aware until he’s flung out of the plane and loses consciousness. Then his narration has to resort to an objective report of what happened while he was out. (“Witnesses said…”) The statement is backed up by a quick, vernacular summary of where and when he landed. The tone then switches to understated reflection, using the flat language of the stoic man of war: Escape wouldn’t have been impossible, or fatal, merely “challenging.” The paragraph plays down the crisis of survival by tapering into ironic self-effacement.

The rule of three is one of the writer’s best friends. The last sentence of the first paragraph renders three McCain actions—radioing, reaching, and pulling—in swift succession. Injuries pile up in triple-formation too: arm, arm, knee. The third trio is casual but memorably repetitive: middle of the lake, middle of the city, middle of the day. Should McCain claim that he, like Hamlet, “uses no art at all,” a narratologist will remind him of the technique pervading this passage—and his book’s opening. In a novel, mentioning a ship called Proteus would foreshadow the changes that young John will undergo. And James Wood complains in his recent How Fiction Works that a great many “apprentice novels” begin with the narrator pondering a family photo (95-96).

Percy Lubbock’s The Craft of Fiction (1921), a classic of literary narratology, distinguishes two methods of narration. The scenic method strives to make each moment palpable through energetic description, while the panoramic one inclines toward summary and generalization. Along this (fairly rough) continuum, Dreams from My Father lies closer to the scenic pole and Faith of My Fathers is closer to the panoramic one. Both autobiographies deploy the rhetoric of fiction, and both are unavoidably artificial. And each one’s technique (subtly eloquent versus direct and plain-spoken) creates a voice that fits the man’s narrative and his public persona.

Peopling the story

Characters in a narrative are usually identified by their roles and their traits of personality. Indiana Jones is a professor and adventurer, an intellectual cowboy. He is courageous, knowledgeable in his field, risk-loving, a bit insolent, somewhat impetuous, and so on. (For more on character construction, see my third essay in Poetics of Cinema.) Given very few cues we can fill in a character, so it becomes important that people who would become characters in their own stories send out the right signals. Rewriting real life is hard.

In the presidential campaign, it isn’t hard to identify the traits that the candidates are trying to define. All want to show integrity, resolve, prudence, a willingness to sacrifice for the greater good, and so on. But each candidate has also become identified with more individual traits. Without my enumerating them, let’s try a game.

Imagine our candidates as people in a high school. (2) Which one is the assistant principal on the verge of retirement? Which one is the social studies teacher who can always be led off the lesson plan with a strategically innocent question? Which one is the earnest first-year teacher, convinced that he can reform secondary education by reaching miscreants? And which one is Miss Popularity, cruel queen of the cliques, bluffing her way through assignments?

Maybe you don’t agree with my assessment of the candidates’ traits, but you knew exactly whom I referred to in each case. That’s because at least one narrative frame has sorted the characters along these lines. It’s a little scary to see that a flesh-and-blood person can be “characterized” so stereotypically, but whatever our political protagonists are like privately or deep down inside, as characters in the narratives that they spin or others spin around them, they fit well-worn templates.

Indeed, they can strive quite consciously to do that. To claim to possess “audacity” or to call yourself a “maverick” is to conjure up a set of traits, and these have implications for how you will act. As your actions mount up, a portrait snaps into focus that is hard to eradicate. Sarah Palin, introduced as a hard-edged fighter in the mold of Hillary Clinton, has been the most obvious instance of gradual revelation. She was an outline waiting to be filled in with events, and despite the campaign’s efforts to control what those events were, damaging pieces of behavior have mounted up and campaign leaks have confirmed their dire side. Palin now stands as a provincial politician adept at small-scale patronage whose ignorance of policy, world affairs, and science is abysmal and invincible. This has not kept some people from admiring her, of course.

Palin betrays no change in personality over the course of the campaign, and neither does Biden. According to reporters who cover him, he’s the same Joe he always was, take it or leave it. For real change—not of America’s direction but of public personas—we need to look at the top of the ticket. In the course of the campaign, for example, Obama has managed to seem consistent with his core program while having “seasoned” and “matured,” thanks to the tough primary fights. (Another cluster of narratives I can’t tackle here.)

McCain has been rendered as changing too, but not in a good way. One prominent large-scale narrative has portrayed him as losing some of his independence of thought [24]—tacking to the right on cultural matters, losing the argument about his running mate. Few speak of the old Barack Obama versus the new one, but the narrative of John McCain 2.0 has stuck. Mr. Roberts has become the captain himself—a man crumpled with vexation, the cranky officer he would have rebelled against at Annapolis. I suspect that some day a McCain biographer will construct a narrative that shows him to have become a tragic figure.

The big three ingredients

Narratives arouse emotions in us; some would say that’s their chief purpose. The emotions can be of all kinds—pity, sympathy, indignation, joy, and down the line. But are there emotions characteristic of narrative in general? The theorist Meir Sternberg (3) has suggested that a narrative as such, regardless of other emotions it can conjure up, depends on three emotional states. Simplifying a bit, we can say that stories create curiosity about past events, suspense about future events, and surprise by means of unexpected events. Whatever other emotions a narrative evokes, we need to feel at least one of these three states.

Most narratives invoke all of these, but some genres rely on more than others. Detective stories rely a lot on curiosity, as characters try to solve the crime by exposing the events that led up to what’s happening now. Likewise, psychological tales—like Obama’s search for his roots—will evoke curiosity about the origins of events or personality traits. Action-driven narratives rely heavily on suspense: Will the protagonist reach her goals, or even just survive? The Dark Knight, with all its ticking clocks and hairbreadth escapes, is driven chiefly by suspense. (For more on suspense, you can visit this entry [25].) Plots with “a sting in the tail,” such as in stories by O. Henry and Roald Dahl and the early films of M. Night Shyamalan, have endings that depend to an unusual degree on surprise.

We can distinguish the two Presidential campaigns’ “master narratives,” along these dimensions. In the ongoing electioneering, Obama’s campaign is now driven almost completely by suspense. He’s not asking us to find out more about what led to the war in Iraq or the economic collapse or the crumbling infrastructure; it’s assumed that we know enough backstory. Everything is about what comes next. Ask any Obama supporter the predominant emotion she or he feels, and I’ll bet it will be suspense. What will happen next? What could throw the juggernaut off course? Fingers crossed: The very image of suspense.

McCain, by contrast, is running a campaign driven by curiosity and surprise. Many of his talking points dwell on the past. Who is Barack Obama, really? What did he have to do with Ayers, Rezko, the Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac executives? Why did he sit in Jeremiah Wright’s church? And so on. These questions ask us to feel curiosity in the form of suspicion about McCain’s rival. The fact that most in his audience haven’t taken up the hint has driven the campaign to try to invoke another emotion: surprise. The pick of Sarah Palin is the most obvious instance, but several others have followed: suspending the campaign, promising to buy people’s mortgages, yanking Joe the Plumber out of obscurity as an emblem of small business, even the “not ready yet” tagline of a recent ad. There may be more surprises to come, as gloomy Democrats fear (which only increases their feeling of suspense). At this point, the act of winning would be the ultimate McCain surprise.

So the campaigns may teach us something of interest about narratives: You can’t have a gripping narrative without some suspense. You can do without curiosity or surprise, but a story lacking suspense won’t keep us turning enough pages to be curious or surprised. (4) Maybe that’s why the McCain campaign never had a “compelling narrative.” It didn’t build up enough of a sense of how it would win or how, after the election, the future would be different.

Narrative plus

On 29 October, the Obama campaign ran a 30-minute television film, American Stories, about why he should be president.This infomercial is a gift to the film analyst, and there’s much more to say about it than I can articulate here. I’ll concentrate on one intriguing aspect of it.

Narrative isn’t the only way to organize a film or literary text. In Film Art, we suggest that there are other principles of organization. Using categorical form, you can survey different types of things, like baseball cards or political systems, without telling a story. You can use a rhetorical format, making an argument for a position you believe in by adducing reasons. What we call associational form can link various images, sounds, and actions through analogy, contrast, or metaphorical connection; one example would be the film Koyaanisqatsi. And very often these principles can combine in a single book, film, or tv program.

American Stories isn’t centrally about Obama’s life or his family or running mate. Instead, the campaign created a series of anecdotal narratives. In turn, these narratives were linked by associations, not by the causal connections typical of narrative. Most broadly, Obama framed these narratives and linkages within a set of policy statements, so that the narratives provided illustrative examples of a rhetorical argument.

A football mom can’t pay for her husband’s medical treatment and must ration the kids’ snacks. An elderly retiree who paid off the family house must return to work to pay for his wife’s medications. A teacher in a school for at-risk kids must take a second job and still find time for her training, while deciding whether to buy a gallon or half-gallon of milk. A loyal Ford assembly-line worker is dropped to half-time; unlike his father and grandfather, he cannot expect a full pension. “Everybody here’s got a story,” Obama remarks.

The stories serve to illustrate a checklist of Obama’s positions: rescuing the middle class by means of tax cuts, making corporations accountable for pension fulfillment, working for energy independence, reforming health care, and shifting the war on terror to Afghanistan. So far, so categorical. But these talking points aren’t linked by logical inference but by association.

Take the story of teacher Juliana Sanchez. She instantiates the ‘education’ idea. Cut to Obama saying that teachers can do only so much: Parents must take responsibility for their children’s learning. Just as Juliana is taking care of her children, Obama recalls his mother taking care of him, as a single parent. Over family photographs he tells of his mother rousing him from bed to go through his lessons before she went to work. Link to Obama giving a speech in which he declares that every child needs a world-class education. Cut to him addressing the camera, declaring that he’s seen school reform work. The political has become doubly personal, exemplified by Juliana and by Obama’s own experience.

Then: “Just as I believe that every American has a right to an affordable education, I also believe that every American has a right to affordable health care.” This segues to a statement of Obama’s medical policy, which is followed by an account of his mother’s premature death, in which he shows that he knows what it is to lose a loved one. “It felt arbitrary.”

While the local connections are driven by associations like these, the overall shape of the half-hour is—no surprise—rhetorical. Obama is adducing reasons to vote for him. His case is that Americans are facing problems to which he has solutions. He could have presented the solutions as a list, in the form of bullet points or charts. Instead, he makes the problems concrete by illustrating how they affect ordinary people, including his own family, and then presents his solution by talking to an audience.

This use of rhetorical form contrasts with the one we discuss in Film Art (Chapter 10), when we analyze The River (1937). In that film, director Pare Lorentz doesn’t highlight individuals’ experience but creates a vast, sweeping story of erosion on the Mississippi river. Correspondingly, Lorentz doesn’t give the solution to the problem as a speech; it is presented in images of people taming the river, building the dam, and settling in new communities.

Obama could have adopted Lorentz’s strategy by tracing a broad history of the last eight years of Republican government, leading up to the financial crisis as a climax of mismanagement, and then turning to his policy prescriptions. He chose, as his campaign has largely chosen, not to rehearse the mistakes and misdeeds of the past (with which many Democrats were involved as well) but to put the emphasis on current conditions and hope for the future. Instead of Lorentz’s epic sweep, which arouses a feeling of grandeur and civic pride in getting a big job done, the Obama film asks us to empathize with “Americans looking for real and lasting change that makes a difference in their lives.”

Thanks to this blend of different types of formal organization, even the abstractions of policy draw upon the powers of storytelling. Maybe this campaign really is all about narratives. If so, maybe narratology can illuminate public discourse in useful ways.

Just don’t call this blog entry a deconstruction.

(1) Roland Barthes, “Introduction to the Structural Analysis of Narratives,” in Image Music Text, ed. and trans. Stephen Heath (New York: Hill and Wang, 1977). Barthes’ essay originally appeared in Communications 8 (1966), devoted to semiological research into narrative. Assembling a veritable who’s who of Structuralism, the issue included essays by Greimas, Bremond, Eco, Todorov, and Genette, as well as Christian Metz’s essay on the “Grand Syntagmatic” of narrative film.

(2) People say that Hollywood is high school with money, and that Washington is Hollywood for ugly people. So Washington must be high school, money, and ugly people? Obama and Palin seem to disprove the last condition.

(3) Sternberg laid out these principles in Expositional Modes and Temporal Ordering in Fiction (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1978), one of the finest studies of narrative theory I know. He elaborated the ideas in two articles under the title “Telling in Time.” See Poetics Today 11, 4 (Winter 1990), 901-948, and 13, 3 (Fall 1992), 463-541.

(4) Of course there is suspense on the McCain side too, but more and more it consists of the question: How bad will the damage be? [28]Although the Obama campaign hasn’t exploited curiosity about McCain’s campaign narrative, the press has done so by slowly creating a backstory about Palin’s record and the way she was selected.