PTU.

DB here:

Films from Hong Kong’s Milkyway company earn a lot of praise for their visual qualities. Shooting in Technovision, Johnnie To Kei-fung and other directors have created some of the most vivid and fluid imagery in contemporary cinema. But the movies have soundtracks too. What about them?

When I saw Tsui Hark’s Time and Tide (2000), I staggered out exhausted. I was overwhelmed not only by the delirious plot and its cascade of feverish imagery—who else puts the camera inside a dryer at a laundromat?—but also by what seemed to me the most elaborate soundtrack I’d ever heard in a Hong Kong film.

Shortly after seeing the movie, I visited the Milkyway headquarters and met Martin Chappell, the sound designer of Time and Tide. (For his credits and his company information, go here [2].) I figured that he could help me hear more in all movies, not just his own.

Years later, during my spring visit to Hong Kong, I got my wish. Martin gave me an interview and sent me several information-packed emails. As I’d hoped, he taught me to listen better.

At the console

Martin Chappell is a concussive burst of enthusiastic energy, an impression aided by the fact that he looks about sixteen. He loves moviemaking and sound design. Growing up in England, he started as a bass guitarist and audio fan, and he studied music and acoustics. When he graduated he worked in sound studios and became a roadie. After a year in Australia, he moved to Hong Kong and got a job in a radio station.

Soon he was working at TNT, creating sound effects for cartoons and dubbing American movies into Mandarin. Hired briefly away by MGM, Martin then shifted to Milkyway. His first effort there was helping on the mix for The Intruder (1996).

Now, with over fourteen years of audio engineering experience, he is sovereign of sound at Milkyway. Ensconced at the heart of Milkyway’s facility, Martin presides over what he calls the Black Hole. The company’s sound studio consists of several rooms, including a Foley studio that is a black hole within the Black Hole.

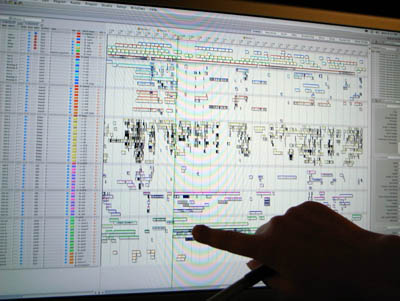

By Hollywood standards, these studios are minuscule. (Compare the mixing theatre I visited last year [4] for 3:10 to Yuma.) As usual in Hong Kong cinema, work must be fast and tight. Martin typically has a sound crew of three, sometimes including Foley artists [5]. Postproduction sound is usually allotted three weeks, sometimes a little longer. Often he has to prepare a mix on short notice so that visiting critics, festival programmers, or backers can preview a work in progress. As a result, Martin can be found in the Black Hole far into the night, blasting through reel after reel.

Waiting for no man

Most Hong Kong films have a bare-bones approach to sound: dialogue, music, and minimal effects. The sort of detailing that Hollywood offers, especially in Foley techniques, has not been common. There simply isn’t the time and money for a densely mixed track. A lot of time has to be allotted for dubbing the film twice, once in Cantonese and once in Mandarin for the mainland and overseas Chinese market. As a result, even the best Hong Kong films often have a dry, vacant ambiance, which is commonly masked by music. (Perhaps the wall-to-wall music in Wong Kar-wai’s films is an effort to supply a rich sound texture in the absence of other options.)

But Time and Tide had more resources. As part of a Sony initiative to expand into Asian production, which also yielded Crouching Tiger and Kitano’s Brother, it had a large budget by Hong Kong standards. Martin had three months for sound postproduction, “the longest schedule I’ve had in my life,” and a sound crew of eight.

Martin found Time and Tide “a beautiful learning experience.” Working around the clock under the tutelage of veteran postproduction supervisor Hui Koan (The Blade, The Legend of Zu), Martin was encouraged to take chances. He could create rich Foley tracks—remember the tinny ricochet of the little boy’s abandoned skateboard?—and he borrowed ideas from Fight Club, Gladiator, and The Matrix. He was layering sound in the Hollywood manner, albeit on a smaller scale. And he pushed toward wilder possibilities. He recalls the pleasure of putting jungle bird calls under early shots of clubbers wandering through nighttime traffic.

Out and about

Hong Kong looks lovely, but Martin thinks that it’s just as breathtaking in its noise—“a rich sonic soup.” Virtually every chance he gets, he heads out to record in the field.

I pretty much never leave home without my Edirol R-09 [8], and I have a Zoom HR [9] for portable hard disc recording.

It’s important to have a recorder with you all the time. You never know when some drunk is going to burst into song whilst lying in the gutter. In Sparrow, Simon Yam challenges Ka Dung to steal the cop’s handcuffs when they’re outside a bar late at night. So I just pulled the recording I’d made earlier of some drunk guys singing karaoke. It was late one night, I was walking back from the pub, and I heard it echoing out an alleyway.

I feel I’m incredibly lucky. I went out one night to get fresh recordings of a minibus for Linger. I’d scouted the spot, but when I got there the heavens opened and I didn’t have an umbrella. I ran to a nearby bridge—serendipity. I realize it’s next to a tram road, so I recorded buses and trams in the rain, and these sounds feature prominently in Sparrow.

Martin’s wife Marisha often comes with him, either operating or providing effects herself. Recording on the fly freshens up his library, and keeps him alert to new possibilities.

I’m always hoping for a gift from the Ear in the Sky. I’m actually trying to type quietly now, but there’s a band playing downstairs and it’s coming through the walls. They sound terrible, but I think it could be used for a bar scene—late night outside somewhere? . . .

You can see Martin on location in a two-part TV show here [10].

Back in the studio, Martin revels in software like his Digital Performer [11] and Propellerhead Reason [12] programs. His setup isn’t a Mercedes, like ProTools, he says, more of a Lexus—but in some ways it’s more flexible than the more famous option. Johnnie To wants rich tracks, so “Now I spend almost all my time on Foley and ambience.” Martin “finds the flavor” of the sound through his synthesizer.

I load a recording into Reason and I can play with it in real time on my keyboard—pitching it up or down, sweeping the filters, tweaking the equalization. I do so much with ambiance like this. Sometimes I tie it to the picture, other times I just play on a whim. . . . It’s almost fun.

Alongside his high-tech equipment, Martin employs some home-made items, such as his gobo panel [13], an upright mesh of stones that is virtually a sculpture (above). The gobo can muffle or redirect sound. Placed between two sources, it can allow clean recording of each track.

Every gun makes its own music

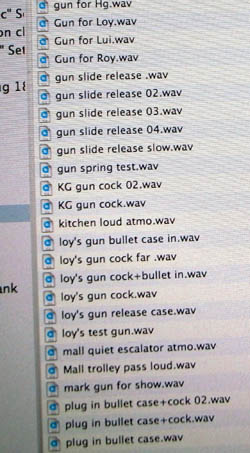

In The Mission, each of the five bodyguards gets a different pistol. Martin gave each one a different sound, labeled in his files by the actor’s name. Here “Roy’s gun” is sometimes coded as “loy’s gun,” and there are plenty of other discrete sound bits on file.

I asked Martin about the mall shootout, which has become a classic in the genre.

There seemed to be so much space in there, and we were adding artificial reverbs, but none of them seemed to work real well. That’s when we decided to experiment a bit, developing things we’d tried in A Hero Never Dies. We just put in the tail of a cannon firing. So that phrase “Bring out the big guns” is literally true here.

There was also a really long gap between some gunshots. We tried adding more, but it felt too busy. So we tried lengthening each gunshot, with the cannon tail reverberating. But that still wasn’t long enough, so we started playing with it, almost jamming with the music. We time-stretched the cannon tails, not just a bit like you’re supposed to. It gave a very artificial but tense sound. If you think it’s music, it might well be.

But even then it wasn’t long enough. So before the next pistol shot, we actually reversed the cannon sound. We get the reversed echo first, then we hear the shot itself! It feels like time has slowed down, then speeded up.

Martin might also have mentioned that these wavering gun reports swoop across left and right channels, creating a dynamic acoustic space for cinema’s most static static gunfight.

Martin also shared his thoughts on the role of sound in fleshing out characterization. After reading Walter Murch’s book In the Blink of an Eye [16] he began to think about how to use sound subjectively. The result was the PTU scene in which Lam Suet, head bandaged, smoking in his car, suffers auditory hallucinations.

Martin acknowledges that there are plenty of conventions that audiences would miss if they weren’t present. When a character hangs up the phone on another character, the disconnected line is signaled through a beep or hum, even though this seldom happens in real life. Martin would also like to hear mobile phone calls in that “headphone bleed-through” effect. He’d also like to handle dialogue like that, “half-overheard, not fully comprehended.”

Still, he finds ways to bypass conventions. In PTU, when the officer played by Simon Yam is abusing the suspect in the video arcade, Martin avoided the library whacking sound, what he calls “the Foley kung-fu cloth flap.” Simon’s slaps are synched to explosions, whizzing missiles, and other arcade sounds. (I offer a visual analysis of one scene in PTU here [17].)

Ear in the sky

Martin believes that in most films, there’s an immediate need to establish the setting, the placement of the characters, and the scene’s mood. This is done through images, of course, but sound plays an important role. Often a wide shot orients us generally, while sound focuses on one zone of action in that space. “I would guess if you watch TV with no sound, it would be very difficult to really focus. Sound can bring out the visual and guide the eye.”

As an example, Martin walked me through a few moments in Sparrow. The elusive Chun Lei has gulled a quartet of pickpockets, and they pursue her to a rooftop. As the men explore it, we hear traffic and a distant plane, which evokes Chun Lei’s plan to flee Hong Kong.

They spot her on the roof. The suggestion that she might jump is underscored by distant traffic horns.

As the men approach Chun Lei, Martin added distant sirens and a soft wind.

An extreme long-shot provides a still broader sound canvas, with traffic sounds predominating.

In a much tighter shot, as the actors come closer to the camera, the ambiance thins and softens. “Now we time the traffic to underline the dialogue.” Chun Lei leans forward to kiss Bo, trying to provoke the leader Kei to jealousy. We hear echoes of a passing truck, almost as a warning.

Only professionals would probably notice these maneuvers, and there’s a reason. Martin thinks that sound can bypass the conscious mind, working directly on our most visceral impulses (fight or flight?). In this he echoes Gary Rydstrom, quoted in an earlier blog of ours [24]: “Film sound is the side door to people’s brains.”

I’m grateful to Martin for all the time and effort he put into our interview. Next time I see a Milkyway film, or any movie, I’ll listen harder. You too?

Photo by Martin Chappell.