Solaris.

Kristin here–

On April 12, Jason Silverman posted a brief piece on Wired: “Writers, Directors Fear ‘Sci-Fi’ Label Like an Attack from Mars [1].” According to Silverman, film studios, book publishers, novelists, film directors, and other involved in the creative process often try to find alternative descriptions when publicizing their work. Thus Cormac McCarthy’s novel The Road is “post-apocalytic” or “dystopian.” The executive producer of Battlestar Gallactica, Ronald D. Moore, is quoted: “It’s fleshed-out reality. It’s not in the science-fiction genre.” Never mind that it plays on the Sci-Fi Channel.

Such obfuscation is not universal. Plenty of works get labeled “science fiction.” Still, according to Silverman, the term sci-fi is dodged “especially when it applies to ‘serious’ fiction or cinema.”

There is something to this, though it needs to be qualified and expanded in a way that Silverman couldn’t do in such a short piece.

I think recent years have actually witnessed a decline in the popularity of sci-fi genre in the cinema. In discussing the impact of The Lord of the Rings in The Frodo Franchise (Chapter 9), I trace the ending of the major sci-fi franchises and the rise of their replacement: fantasy franchises. Already in late 2002, Lev Grossman wrote a perceptive article for Time, “Feeding on Fantasy [2]” that noted the downward trend in sci-fi and the concurrent rise in the popularity of fantasy.

Fantasy films used to be considered box-office poison. In the January 2002 issue of Empire, Adam Smith published “Fantasy Island,” (which I can’t find online) listing a whole series of fantasy duds (Willow, anyone?). For some reason, Smith and some other like-minded commentators on this subject ignore the work of Tim Burton, whose Beetle Juice (1988) and Edward Scissorhands (1990) are surely classics of the genre.

Now perhaps it is science fiction that has become dubious box-office fare. Since 2000, sci-fi hits that were not part of an established franchise have been few and far between: War of the Worlds (2005), I, Robot (2004), and Planet of the Apes (2001). The first two had the advantage of starring two of the most popular actors in the world. Minority Report (2002) was considered a solid success, and again it had the advantage of Tom Cruise and Steven Spielberg’s names attached.

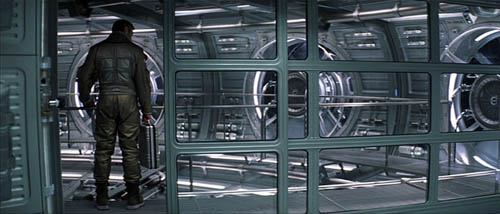

OK, Battlefield Earth was an unparalleled flop, but middling to disastrous sci-fi releases are easy to find (and here I’m defining sci-fi according to the genre lists on Box Office Mojo). Among the also-rans: AI: Artificial Intelligence (2001), The Adventures of Pluto Nash (2002), Solaris (2002), Simone (2002), The Time Machine (2002), Rollerball (2002), The Stepford Wives (2004), Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy (2005), and, perhaps cursed by its title, Doom (2005).

Even Joss Whedon, who had tremendous success with Buffy the Vampire Slayer and its spin-offs, hit a brick wall with his sci-fi TV series Firefly and its film continuation Serenity (2005).

Fantasy, on the other hand, has become so prominent and so successful that it is hardly necessary to list examples. X-Men, Spider-Man, Rings, Harry Potter, The Chronicles of Narnia, and Pirates of the Caribbean are hugely popular franchises. Add on animated fantasies like those made by Pixar, and fantasy practically rules the box office. A surprising number of current big-budget projects are fantasies (among the most prominent, His Dark Materials: The Golden Compass).

By the way, here I include both the X-Men and Spider-Man series as fantasy rather than science fiction, which is debatable. Each offers some sort of physical explanation for the super-powers of their characters: various genetic mutations of uncertain cause, a spider bite during a school lab fieldtrip. These are not scientific explanations, though, at least not of the semi-plausible sort that sci-fi films usually delight in providing.

Genres move in cycles, and sci-fi films will probably return to prominence. For the moment, though, cable television seems to have become the medium where sci-fi thrives. Battlestar Galactica is one example. MGM is currently using the success of its “stalwart” Stargate series to move into foreign television markets. (For a Variety [3] story, click here.) Stargate already has one spinoff, another is in the works, and two movies are planned. (Maybe MGM should reconsider that last idea.) There’s always the possibility of another Star Trek TV series.

Sci-fi films are far from moribund, however, and not everyone shuns calling them by that name. Most obviously, James Cameron’s ambitious project Avatar, currently announced for May 22, 2009, is underway. (The announcement in Variety [2] calls it a sci-fi film.) A film often referred to as Star Trek XI [4] has a release date of December 25, 2008.

Silverman’s article expresses puzzlement that in an era when science is such a prominent part of our lives, the genre of science fiction should loose favor. My own guess would be that it is precisely because technology is advancing at such a dizzying rate that stories about a real or alternative future may seem a bit tame.

When we casually refer to robots as “bots,” have mechanical dogs in our homes, and watch rovers photographing Mars, are films about robots quite as interesting as they used to be? Unless they star Will Smith, of course. When companies are actually planning to offer space tourism to paying customers within some of our lifetimes, are fictional rocket ships as intriguing? And perhaps we have simply by now seen stories based on these subjects a bit too often. Perhaps to find renewed respectability, the genre needs to move beyond its most familiar conventions.

Willow.