Archive for the 'Screenwriting' Category

David Koepp: Making the world movie-sized

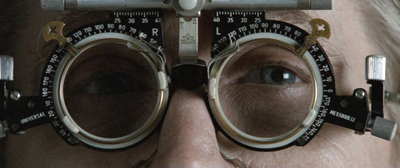

Stir of Echoes (1999).

DB here:

For a long time, Hollywood movies have fed off other Hollywood movies. We’ve had sequels and remakes since the 1910s. Studios of the Golden Era relied on “swipes” or “switches,” in which an earlier film was ripped off without acknowledgment. Vincent Sherman talks about pulling the switch at Warners with Crime School (1938), which fused Mayor of Hell (1933) and San Quentin (1937). Films referred to other films too, sometimes quite obliquely (as seen in this recent entry).

People who knock Hollywood will say that this constant borrowing shows a bankruptcy of imagination. True, there can be mindless mimicry. But any artistic tradition houses copycats. A viable tradition provides a varied number of points of departure for ambitious future work. Nothing comes from nothing; influences, borrowings, even refusals–all depend on awareness of what went before. The tradition sparks to life when filmmakers push us to see new possibilities in it.

From this angle, the references littering the 1960s-70s Movie Brats’ pictures aren’t just showing off their film-school knowledge. Often the citations simply acknowledge the power of a tradition. When Bonnie, Clyde, and C. W. Moss hide out in a movie theatre during the “We’re in the Money” sequence from Gold Diggers of 1933, the scene offers an ironic sideswipe at their bungled bank job, and a recollection of Warner Bros. gangster classics. When a shot in Paper Moon shows a marquee announcing Steamboat Round the Bend, it evokes a parallel with Ford’s story about an older man and a girl. Even those who despised the tradition, like Altman, were obliged to invoke it, as in the parodic reappearances of the main musical theme throughout The Long Goodbye.

But tradition is additive. As the New Hollywood wing of the Brats—Lucas, Spielberg, De Palma, Carpenter, and others—revived the genres of classic studio filmmaking, they created modern classics. The Godfather, Jaws, Star Wars, Carrie, Raiders of the Lost Ark, and others weren’t only updated versions of the gangster films, horror movies, thrillers, science-fiction sagas, and adventure tales that Hollywood had turned out for years. They formed a new canon for younger filmmakers. Accordingly, the next wave of the 1980s and 1990s referenced the studio tradition, but it also played off the New Hollywood. For “New New Hollywood” directors like Robert Zemeckis and James Cameron, their tradition included the breakthroughs of filmmakers only a few years older than themselves.

So today’s young filmmaker working in Hollywood faces a task. How to sustain and refresh this multifaceted tradition? One filmmaker who writes screenplays and occasionally directs them has found some lively solutions.

From the ’40s to the ’10s

The Trigger Effect (1996).

David Koepp was fourteen when he saw Star Wars and eighteen when he saw Raiders. By the time he was twenty-nine he was writing the screenplay for Jurassic Park. Later he would provide Spielberg with War of the Worlds (2005) and Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull (2008). Across the same period he worked with De Palma (Carlito’s Way, 1993; Mission: Impossible, 1996; Snake Eyes, 1998), and Ron Howard (The Paper, 1994), as well as younger directors like Zemeckis (Death Becomes Her, 1992), Raimi (Spider-Man, 2002), and Fincher (Panic Room, 2002). The young man from Pewaukee, Wisconsin who grew up with the New Hollywood became central to the New New Hollywood, and what has come after.

He spent two years at UW–Madison, mostly working in the Theatre Department but also hopping among the many campus film societies. He spent two years after that at UCLA, enraptured by archival prints screened in legendary Melnitz Hall. The result was a wide-ranging taste for powerful narrative cinema. He came to admire 1970s and 1980s classics like Annie Hall, The Shining, and Tootsie. As a director, Koepp resembles Polanski in his efficient classical technique; his favorite movie is Rosemary’s Baby, and one inspiration for Apartment Zero (1988) and Secret Window was The Tenant. You can imagine Koepp directing a project like Frantic or The Ghost Writer.

Old Hollywood is no less important to Koepp. Among his favorites are Double Indemnity, Mildred Pierce, and Sorry, Wrong Number. In conversation he tosses off dozens of film references, from specifically recalled shots and scenes to one-liners pulled from classics, like the “But with a little sex” refrain from Sullivan’s Travels.

It’s not mere geek quotation-spotting, either. The classical influence shows up in the very architecture of his work. He creates ghost movies both comic and dramatic, gangster pictures, psychological thrillers, and spy sagas. The Paper revives the machine-gun gabfests of His Girl Friday, while Premium Rush gives us a sunny update of the noir plot centered on a man pursued through the city by both cops and crooks.

One of the greatest compliments I ever got (well, it seemed like a compliment to me, anyway) was when Mr. Spielberg told me I’d missed my era as a screenwriter–that I would have had a ball in the 40s.

Like his contemporary Soderbergh, Koepp sustains the American tradition of tight, crisp storytelling. He also thinks a lot about his craft, and he explains his ideas vividly. His interviews and commentary tracks offer us a vein of practical wisdom that repays mining. It was with that in mind that I visited him in his Manhattan office to dig a little deeper.

Humanizing the Gizmo

Today, the challenge is the tentpole, the big movie full of special effects. A tentpole picture needs what Koepp calls its Gizmo, its overriding premise, “the outlandish thing that makes the big movie possible.” The Gizmo in in Jurassic Park is preserved DNA; the Gizmo in Back to the Future is the flux capacitor. “The more outlandish the Gizmo, the harder it is to write everybody around it.” The problem is to counterbalance scale with intimacy. “You need to offset what’s ‘up there’ [Koepp raises his arm] with things that are ‘down here’ [he lowers it].” This involves, for one thing, humanizing the characters. A good example, I think, is what he did with Jurassic Park.

Crichton’s original novel has a lot going for it: two powerful premises (reviving dinosaurs and building a theme park around them), intriguing scientific speculation, and a solid adventure framework. But the characterizations are pallid, the scientific monologues clunky, and the succession of chases and narrow escapes too protracted.

The film is more tightly focused. In the novel, Dr. Grant is an older widower and has no romantic relation to Ellie; here they’re a couple. In the original, Grant enjoys children; in the film, he dislikes them. Accordingly, Koepp and Spielberg supply the traditional second plotline of classic Hollywood cinema. Alongside the dinosaur plot there’s an arc of personal growth, as Grant becomes a warmer father-figure and he and Ellie become short-term surrogate parents for Tim and Alexa.

Similarly, Crichton’s hard-nosed Hammond turns into a benevolent grandfather; in the film, his defensive attitude toward the park’s project collapses when his children are in danger. Even Ian Malcolm, mordantly played by Jeff Goldblum (stroking some of the most unpredictable line-readings in modern cinema), can be seen as the wiseacre uncle rather than the smug egomaniac of the novel.

Crichton’s tale of scientific overreach becomes a family adventure. Koepp’s consistent interest in the crises facing a family meshes nicely with the same aspect of Spielberg’s work, and it gives the film an appeal for a broad audience. In the original, Tim is a boy wonder, well-informed about dinosaurs and skilled at the computer. Koepp’s screenplay shares out these areas of expertise, making Lex the hacker and letting her save the day by rebooting the park’s defense system. There’s a model of courage and intelligence for everybody who sees the movie.

While giving Crichton’s novel a narrative drive centered on the surrogate family, Koepp also creates a more compressed plot. For one thing, he slices out the chunks of scientific explanation that riddle the novel. The main solution came, Koepp says, when Spielberg pointed out that modern theme parks have video presentations to orient the visitors. Koepp and Spielberg created a short narrated by “Mr. DNA,” in an echo of the middle-school educational short “Hemo the Magnificent.” The result provides an entertaining bit of exposition that condenses many scenes in the book. Why Mr. DNA has a southern accent, however, Koepp can’t recall.

Compression like this allows Koepp to lay the film out in a well-tuned structure. Most of his work fits the four-part model discussed by Kristin and me so often (as here). In Storytelling in the New Hollywood, she shows how Jurassic displays the familiar pattern of goals formulated (part one), recast (part two), blocked (part three), and resolved (part four). When I visited Koepp, he was laying out 4 x 6 cards for his screenplay for Brilliance, seen above. He remarked that the array fell into four parts, with a midpoint and an accelerating climax.

For a smaller-scale example of compression, consider a classic convention of heist movies: the planning session. In Mission: Impossible, Ethan Hunt reviews his plan for accessing the computer files at CIA headquarters. As he starts, the reactions of the two men he’s recruiting foreshadow what they’ll do during the break-in: the sinister calculation of Krieger (Jean Reno), in particular, is emphasized by De Palma’s direction. Ethan’s explanation of the security devices shifts to voice-over and we leave the train compartment to follow an ineffectual bureaucrat making his way into the secured room. (The room and the gadgets were wholly made up for the film; the Langley originals were far more drab and low-tech.)

Everything that will matter later, including the heat-sensitive floor and the drop of moisture that can set off the alarms, is laid out visually with Ethan’s explanation serving as exposition. Like the Mr. DNA short, this set-piece, extravagant in the De Palma mode, serves to specify how things in this story will work. Here, however, the task involves what Koepp calls “baiting the suspense hook. “ Each detail is a security obstacle that Hunt’s team will have to overcome.

The world is too big

Panic Room.

The overriding problem, Koepp says, is that the world is too big for a movie. There are too many story lines a plot might pursue; there are too many ways to structure a scene; there are too many places you might put the camera. You need to filter out nearly everything that might work in order to arrive at what’s necessary.

At the level of the whole film, Koepp prefers to lay down constraints. He likes “bottles,” plots that depend on severely limited time or space or both. The Paper ’s action takes 24 hours; Premium Rush’s action covers three. Stir of Echoes confines its action almost completely to a neighborhood, while Secret Window mostly takes place in a cabin and the area around it. Even those plots based on journeys, like The Trigger Effect and War of the Worlds, develop under the pressure of time.

Panic Room is the most extreme instance of Koepp’s urge for concentration. He wanted to have everything unfold in the house during a single night and show nothing that happened outside. (He even thought about eliminating nearly all dialogue, but gave that up as implausible: surely the home invaders would at least whisper.) As it worked out, the action in the house is bracketed by an opening scene and closing scene, both taking place outdoors, but now he thinks that these throw the confinement of the main section into even sharper relief. The result is a tour de force of interiority—not even flashbacks break us out of the immense gloom of the place—and in the tradition of chamber cinema it gives a vivid sense of the overall layout of the premises.

Panic Room, like Premium Rush, relies on crosscutting to shift us among the characters and compare points of view on the action. But another way to solve the world-is-too-big problem is to restrict us to what only one characters sees, hears, and knows. This is what Polanski does in Rosemary’s Baby, which derives so much of its rising tension from showing only what Rosemary experiences, never the plotting against her. Koepp followed the same strategy in War of the Worlds. Most Armageddon films offer a global panorama and a panoply of characters whose lives are intercut. But Koepp and Spielberg decided to show no destroyed monuments or worldwide panics, not even via TV broadcasts. Instead, we adhere again to the fate of one family, and we’re as much in the dark as Ray Ferrier and his kids are. Even when Ray’s teenage son runs off to join the military assault, we learn his fate only when Ray does.

Less stringent but no less significant is the way the comedy Ghost Town follows misanthropic dentist Bertram Pincus (Ricky Gervais). After a prologue showing the death of the exploitative exec played by Greg Kinnear, we stay pretty much with Pincus, who discovers that he can see all the ghosts haunting New York. Limiting us to what he knows enhances the mystery of why these spirits are hanging around and plaguing him.

Yet sticking to a character’s range of knowledge can create new problems. In Stir of Echoes, Koepp’s decision to stay with the experience of Tom Witzky (Kevin Bacon) meant that the film would give up one of the big attractions of any hypnosis scene—seeing, from the outside, how the patient behaves in the trance. Koepp was happy to avoid this cliché and followed Richard Matheson’s original novel by presenting what the trance felt like from Tom’s viewpoint.

The premise of Secret Window, laid down in Stephen King’s original story, obliged Koepp to stay closely tied to Mort Rainey’s range of knowledge. In his director’s commentary, Koepp points out that this constraint sacrifices some suspense, as during the scene when Mort (Johnny Depp) thinks someone else is sneaking around his cabin. We can know only what he sees, as when he glimpses a slightly moving shoulder in the bathroom mirror.

Having nothing to cut away to, Koepp says, didn’t allow him to build maximum tension. Still, the film does shift away from Mort occasionally, using a little crosscutting during phone conversations and at the climax. During the big revelation, Koepp switches viewpoint as Mort’s wife arrives at the cabin; but this seems necessary to make sure the audience realizes that the denouement is objective and not in Mort’s head.

Once you’ve organized your plot around a restrictive viewpoint, breaking it can be risky. About halfway through Snake Eyes, Koepp’s screenplay shifts our attachment from the slimeball cop Rick Santoro (Nicolas Cage) to his friend Kevin (Gary Sinese). We see Kevin covering up the assassination. In the manner of Vertigo, we’re let in on a scheme that the protagonist isn’t aware of. This runs the risk of dissipating the mystery that pulls the viewer through the plot. Sealing the deal, Snake Eyes then gives us a flashback to the assassination attempt. Not only does this sequence confirm Kevin’s complicity, it turns an earlier flashback, recounted by Kevin to Rick, into a lie. Although lying flashbacks have appeared in other films, Koepp recalls that the preview audience rejected this twist. The lying flashback stayed in the film because the plot’s second half depended on the early revelation of Kevin’s betrayal.

Because the world is too big, you need to ask how to narrow down options for each scene as well as the whole plot. Fiction writers speak of asking, “Whose scene is it?” and advise you to maintain attachment to that character throughout the scene. The same question comes up with cinema.

Say the husband is already in the kitchen when the wife comes in. If you follow the wife from the car, down the corridor, and into the kitchen, we’re with her; we’ll discover that hubby is there when she does. If instead we start by showing hubby taking a Dr. Pepper out of the refrigerator and turning as the wife comes in, it’s his scene. Note that this doesn’t involve any great degree of subjectivity; no POV shot or mental access is required. It’s just that our entry point into the scene comes via our attachment to one character rather than another.

Here’s a moment of such a directorial choice in Stir of Echoes. Maggie comes home to find her husband Tom, driven by demands from their domestic ghost, digging up the back yard. Koepp could have gotten a really nice depth composition by showing us a wide-angle shot of Tom and his son tearing up the yard, with Maggie emerging through the doorway in the background. That way, we would have known about the mess before she did.

Instead, Koepp reveals that Tom’s mind has gone off the rails by showing Maggie coming out onto the back porch and staring. We hear digging sounds. “Oh…kay…” she sighs.

She walks slowly across the yard, passing their son and eventually confronting Tom, who’s so absorbed he doesn’t hear her speak to him.

Once you’ve made a choice, though, other decisions follow. So Maggie provides our pathway into the scene, but how do we present that? Koepp asks on his commentary track:

What do you think? Is it better to do what I did here, which is pull back across the yard and slowly reveal the mess he’s made, or should I have cut to her point of view of the big messy yard right in the doorway? I went for lingering tension rather than the sudden cut to what she sees. You might have done it differently.

Sticking with a central character throughout a scene can have practical benefits too. Koepp points out that his choice for the Stir of Echoes shot was affected by the need to finish as the afternoon light was waning. Similarly, in the forthcoming Jack Ryan, Koepp includes an action scene showing an assault on a helicopter carrying the hero. Koepp’s script keeps us inside the chopper as a door is blown off and Ryan is pinned under it. Rather than including long shots of the attack, it was easier and less costly to composite in partial CGI effects as bits of action glimpsed in the background, all seen from within the chopper.

Saving it, scaling it, buttoning it

Ghost Town.

Because the world is too big, you can put the camera anywhere. Why here rather than there?

Standard practice is to handle the scene with coverage: You film one master shot playing through the entire scene, then you take singles, two-shots, over-the-shoulders, and so on. Actors may speak their lines a dozen times for different camera setups, and the editor always has some shot to cut to. Alternatively, the director may speed up coverage by shooting with many cameras at once. Some of the dialogues in Gladiator were filmed by as many as seven cameras. “I was thinking,” said the cinematographer, “somebody has to be getting something good.”

Koepp opposes both mechanical and shotgun coverage. Whenever he can, he seizes on a chance to handle several pages of dialogue in a single take (a “one-er”). “There’s a great feeling when you find the master and can let it run.” Sustained shots work especially well in comedy because they allow the actors to get into a smooth verbal rhythm. The hilariously cramped three-shot in Ghost Town (shown above) could play out in a one-er because Koepp and Kamps meticulously prepared its rapid-fire dialogue exchange.

When cutting is necessary, Koepp favors building scenes through subtle gradations of scale, saving certain framings for key moments. He walked me through a striking example, a five-minute scene in Panic Room.

Meg Altman and her daughter Sarah have been besieged by home invaders. Meg has managed to flee from their sealed safety room, but Sarah is trapped there and is slipping into a diabetic coma while the two attackers hold her captive. Now two policemen, summoned by Meg’s husband, come calling. The criminals are watching what’s happening on the CC monitor. Meg must drive the cops away without arousing suspicion, or the invaders will let Sarah die.

Koepp’s scene weaves two strands of suspense, the peril of the girl and Meg’s tactics of dealing with the cops. One cop is ready to leave her alone, but another is solicitous. Meg offers various excuses for why her husband called them—she was drunk, she wanted sex—but the concerned cop persists. The scene develops through good old shot/ reverse-shot analytical editing, with variations in scale serving to emphasize certain lines and facial reactions.

At the climax, the concerned officer says that if there’s anything she wants to tell them but cannot say explicitly, she could blink her eyes as a signal. When he asks this, Fincher cuts in to the tightest shot yet on him. The next shot of Meg reveals her decision. She refuses to blink.

Fincher saved his big shot of the cop for the scene’s high point. The cop’s line of dialogue motivates the next shot, one that keeps the audience in suspense about how Meg will respond. What I love about this shot is that everybody in the theatre is watching the same thing: her eyes. Will she blink?

Building up a scene, then, involves holding something back and saving it for when it will be more powerful. An extreme case occurs in Rosemary’s Baby. I asked Koepp about a scene that had long puzzled me. Rosemary and Guy have joined their slightly dotty older neighbors, the Castevets, for drinks and dinner. Having poured them all some sherry, Castavet settles into a chair far from the sofa area, where the other three are seated.

Mr. Castevet continues to talk with them from this chair, still framed in a strikingly distant shot.

Koepp agreed that virtually no director today would film the old man from so far back. Can’t you just see the tight close-up that would hint at something sinister in his demeanor?

We found the justification in the next scene, the dinner. This is filmed with one of those arcing tracks so common today when people gather at a table, but here it has a purpose. The shot’s opening gives us another instance of the Castevets’ social backwardness, as Rosemary saws away at her steak. (You’d think people in league with Satan could afford a better cut of meat.)

Mr. Castevet proceeds to denounce organized religion and to flatter Guy’s stage performance in Luther. As the camera moves on, the fulcrum of the image becomes the old man, now seen head-on from a nearer position.

“He was saving it,” said Koepp. “He was making us wait to see this guy more closely—and even here, he’s postponing a big close-up.”

Yet having given with one hand, Polanski takes away with the other. Next Rosemary is doing the dishes with Mrs. Castevet while the men share cigarettes in the parlor. Because we’re restricted to Rosemary’s range of knowledge, we see what she sees: nothing but wisps of smoke in the doorway.

We’ll later realize that this offscreen conversation between Roman and Guy seals the deal over Rosemary’s first-born.

Empty doorways form a motif in the film (the major instance has been much commented on), and they too point up Polanski’s stinginess—or rather, his economy. He doles his effects out piece by piece, and the result is a mix of mystery and tension that will pay off gradually. Koepp likewise exploits the sustained empty frame, most notably at the end of Ghost Town.

Building up scenes in this way encourages the director to give each shot a coherence and a point. Koepp recalls De Palma’s advice: “For every shot, ask: What value does it yield?” Spielberg comes to the set with clear ideas about the shots he wants, and when scouting or rehearsing he’s trying to assure that the set design, the lighting, and the blocking will let him make them. As Koepp puts it, Spielberg is saying: “This is my shot. If I can’t do X, I don’t have a shot.”

Compared to the swirling choppiness on display in much modern cinema–say, at the moment, Leterrier’s Now You See Me–Koepp’s style is sober and concentrated. For him, the director should strive to turn a shot into a cinematic statement that develops from beginning to end. The slow track rightward in Stir of Echoes has its own little arc, following Maggie leaving the porch, moving past their son, concluding on Tom as she speaks to him and he suddenly turns to her (at the cut).

Accordingly a shot can end with a little bump, a “button” that’s the logical culmination of the action. Something as simple as Rosemary turning her head to look sidewise is a soft bump, impelling the POV shot of the doorway. Something more forceful comes in Stir of Echoes, when the people at the party chatter about hypnosis and the camera slowly coasts in on Tom, gradually eliminating everybody else until in close-up he says cockily, “Do me.”

Shooting all the conversational snippets among various characters would have required lots of coverage, and it was cleaner to keep them offscreen as the camera drew in on Tom. With the suspense raised by the track-in (a move suggested by De Palma), Koepp could treat Tom’s line as a dramatic turning point and the payoff for the shot.

In a comic register, the button can yield a character-based gag. Bertram Pincus is warming to the Egyptologist Gwen; he’s even bought a new shirt to impress her. They discuss how his knowledge of abcessed teeth can help her research into the death of a Pharaoh. A series of gags involves Pincus’ discomfiture around the mummy, with Gwen making him touch and smell it. The two-shot, Koepp says, is still the heart of dialogue cinema, especially in comedy.

Bertram offers Gwen a “sugar-free treat” and shyly turns away. The gesture reveals that he’s forgotten to take the price tag off his shirt.

This buttons up the shot with an image that reveals the characters’ attitudes. Pincus’s error undercuts his self-important explanation of the pharoah’s oral hygiene. Yet it’s a little endearing; he was in such a hurry to make a good impression he forgot to pull the tag. At the same, having Gwen see the tag shows her sudden awareness that Bertram’s offensiveness masks his social awkwardness. As Koepp puts it: “He bought a new shirt for their meeting, she realizes it, and she finds it sweet.” She’s starting to like him, as is suggested when she turns and matches his posture.

Koepp gives the whole scene its button by cutting back to a long shot as Pincus murmurs, “Surprisingly delightful.” Is he referring to his candy, or his growing enjoyment of Gwen’s company? Both, probably: He’s becoming more human.

Like the Movie Brats and the New New Hollywood filmmakers, Koepp is inspired by other films. And as with them, his usage isn’t derivative in a narrow sense. He treats a genre convention, a situation, an earlier Gizmo, or a fondly-remembered shot as a prod to come up with something new. Borrowing from other films isn’t unoriginal; in mainstream filmmaking, originality usually means revising tradition in fresh, personal ways.

There’s a lot more to be learned about screenwriting and directing from the work of David Koepp. He told me much I can’t squeeze in here, about the Manhattan logistics of shooting Premium Rush and about the newsroom ethnography behind The Paper, written with his brother Stephen. What I can say is this: He really should write a book about his craft. I expect that it would be as good-natured as his lopsided grin and quick wit. It would illuminate for us the range of the creative choices available in the New Hollywood, the New New Hollywood, and the Newest Hollywood.

Thanks to David for giving me so much of his time. We initially came into contact when he wrote to me after my blog post on Premium Rush, which now contains a P.S. extracted from his email. We had never met, and I’m glad we finally caught up with each other.

I’ve supplemented my conversation with David with ideas drawn from his DVD commentaries for Stir of Echoes, Secret Window, and Ghost Town. Soderbergh provides intriguing observations on the commentary track for Apartment Zero. I’ve also found useful comments in these published interviews: “David Koepp: Sincerity,” in Patrick McGilligan, ed., Backstory 5: Interviews with Screenwriters of the 1990s (University of California Press, 2010), 71-89; Joshua Klein “Writer’s Block, [1999],” at The Onion A.V. Club; Steve Biodrowski, “Stir of Echoes: David Koepp Interviewed [2000]” at Mania; Josh Horowitz, “The Inner View–David Koepp [2004]” at A Site Called Fred; “Interview: David Koepp (War of the Worlds)[2005]” at Chud.com; Ian Freer, “David Koepp on War of the Worlds [2006],” at Empire Online; “Peter N. Chumo III, “Watch the Skies: David Koepp on War of the Worlds,” Creative Screenwriting 12, 3 (May/June 2005), 50-55; E. A. Puck, “So What Do You Do, David Koepp? [2007]” at Mediabistro; Nell Alk, “David Koepp, John Kamps Talk Premium Rush, Joseph Gordon-Levitt’s Fearlessness and Pedestrian ‘Scum’ [2012]” at Movieline; and Fred Topel, “Bike-O-Vision: David Koepp on Premium Rush and Jack Ryan [2012]” at Crave Online.

Vincent Sherman discusses screenplay switching in People Will Talk, ed. John Kobal (Knopf, 1986), 549-550. My quotation from Gladiator‘s DP comes from The Way Hollywood Tells It, p. 159. For more on David Fincher’s way with characters’ eyes, see this entry on The Social Network.

A Hobbit is chubby, but is he padded?

Kristin here:

On July 14 at this year’s Comic-Con, a thirteen-minute montage of clips from The Hobbit was shown during an appearance by Peter Jackson and cast members of the film. Afterward in press interviews, Jackson unexpectedly hinted that The Hobbit, long announced as being made in two parts to be released in December 2012 and 2013, might be expanded to three parts. This possibility inspired much skepticism among fans and members of the press. And yet only two weeks later, on July 30, it was announced that The Hobbit would indeed be released in three parts, the third to appear in the summer of 2014.

Although some fans of the film of The Lord of the Rings were delighted, there was much speculation in the press that the move was made from sheer greed, milking a third blockbuster from Tolkien’s modest children’s book. There were even some accusations that Jackson had lost his creativity and was seeking to extend his most successful series beyond its logical stopping point.

Yet if one reads the filmmakers’ statements about the decision to make an additional part of The Hobbit, it is clear that they intend to add more plot material rather than stretching the story of the relatively short novel. There is plenty of additional, directly relevant material in Tolkien’s appendices to LOTR. None of it is given in enough detail to make a free-standing film. Still, no doubt the filmmakers and the production studio began to realize that they had the rights to all this material, and that incorporating some of it into The Hobbit was their only chance to use it. Warner Bros. surely was delighted at the prospect of another lucrative blockbuster.

I’m not convinced, however, that Jackson’s team made their decision primarily from considerations of money. For one thing, some of the material from the appendices was created by Tolkien to tie the events of The Hobbit to those of LOTR. The filmmakers could use it for that same purpose. So far, the trailers and images from the forthcoming film seem to me quite promising in terms of how the appendices have been quarried for useful story items.

It happens that for avid fans of Tolkien, this is a special moment. It’s Tolkien Week. Ever since 1978, the week in which September 22 occurs is dedicated to The Professor, as he is respectfully known to devotees. And September 22 is Hobbit Day, because it is the shared birthday of Bilbo Baggins (who turned 111 on the occasion of the Long-Expected Party that opens the book) and his adopted nephew Frodo (who turned 33, the age of adulthood for Hobbits).

Warner Bros. and the filmmakers have shrewdly chosen this week to release the second trailer for The Hobbit (not counting the teaser). It appeared online on September 19, with the best-quality versions on Apple. (A high-quality version of the first trailer can be seen here.) There’s also a site where you can watch the trailer with five alternative endings, all of them humorous. (The Bilbo one is undoubtedly the best, though I enjoyed the Gandalf one as well. The Dwarf ending is actually the same as in the theatrical version.) The first part of The Hobbit is due out on December 14 in the USA and many markets, and on other dates in December elsewhere.

From two parts to three

I have a uniform paperback edition of the two novels where The Hobbit runs 272 pages and The Lord of the Rings, not counting the appendices or Prologue, runs 993 pages. So The Hobbit is less than a third the length of its sequel. The implication would seem to be that in order to be comparable to Jackson’s version of LOTR, its film adaptation should occupy a single part of perhaps three hours.

Of course LOTR, even in its eleven-and-a-half-hour extended DVD versions, left out a great deal of Tolkien’s novel. (Excision was Tolkien’s expressed preference, by the way, for a film adaptation. In a letter disapproving of a 1957 treatment for a proposed film of LOTR, he stated that cutting scenes was far preferable to racing through a complete but compressed version.) Still, given the huge success of the three-part film, it seemed reasonable that Jackson and company would treat The Hobbit more fully, eliminating less and giving fans a more complete version of the earlier book.

But three parts for The Hobbit? Especially when this change was sprung on the public less than six months before the world premiere of the first part (November 28 in Wellington)? The move proved controversial and has been argued and speculated about ever since. Every trailer, every scrap of footage (especially the 13-minutes of clips shown at Comic-Con and still not available to anyone who was not in Hall H on July 14), every photograph has been closely examined for hints of what extra material might be included in an expanded Hobbit.

The reactions have generally been of four types. Keen fans of Jackson’s LOTR are delighted, trusting him and his fellow screenwriters, Fran Walsh and Philippa Boyens, to come up with extra material true, if not to the book, at least to the spirit of the first film. Others are more skeptical, feeling that Jackson’s team is being too ambitious and is trying to stretch the book’s contents too far. After all, it was written as a children’s novel, not an epic romance like LOTR. A third group simply accuses Jackson of opportunism, whether his own or mandated by greedy corporate types at Warner Bros. (parent company of production unit New Line). Finally, a few commentators view the move as evidence of artistic “stagnation” on Jackson’s part

Most prominent among those in the fourth camp is James Russell, who wrote a piece baldly entitled “Peter Jackson’s three Hobbit films suggest he is running on empty,” for The Guardian. He argues that Jackson had never had a commercial success before LOTR, and that his post-LOTR films have been neither as lucrative nor as critically praised. Now, Russell suggests, Jackson has returned to familiar territory, despite having initially hired Guillermo del Toro to do the directing honors:

It’s hard to see how making The Hobbit could be seen as a positive step for Jackson. However, splitting the story into three separate films takes the moribund self-absorption of the project to entirely new levels. It looks as if Jackson is running entirely on empty, pushing this side project to ridiculous extremes because he has nothing else to offer.

(See also IndieWire‘s “An Open Letter to Peter Jackson on Splitting The Hobbit into Three Movies.”)

Jackson inadvertently encouraged such an interpretation back in the early days of pre-production, when del Toro was still the designated director. He said that he had visited Middle-earth once and did not want to compete with himself. Even when del Toro exited the project in late May, 2010, Jackson said he would not step into the job unless no one else could be found and the project was in danger of falling apart. Asked when the production process would move forward, he responded: “I just don’t know now until we get a new director. The key thing is that we don’t intend to shut the project down…We don’t intend to let this affect the progress. Everybody, including the studio, wants to see things carry on as per normal. The idea is to make it as smooth a transition as we can.”

The announcement that Jackson would in fact direct The Hobbit was not made until mid-October, and his statement in the press release was notably bland: “Exploring Tolkien’s Middle-earth goes way beyond a normal film-making experience. It’s an all-immersive journey into a very special place of imagination, beauty and drama. We’re looking forward to re-entering this wondrous world with Gandalf and Bilbo – and our friends at New Line Cinema, Warner Brothers and MGM.” Nevertheless, he has assured the public that once he agreed to direct, his immersion in pre-production re-ignited his enthusiasm for working with Tolkien’s material. Judging by the two trailers, as well as the eight video production diary entries so far posted on Jackson’s FaceBook page, that enthusiasm is genuine. The expansion of the film to three parts is another indicator that he has been inspired by his return to Middle-earth.

Not padding but extension

Major spoilers ahead! Page and chapter numbers from the two novels are from the most definitive versions of the texts: for The Hobbit, Douglas Anderson’s The Annotated Hobbit, second edition, and the 50th anniversary single-volume edition of LOTR, edited by Wayne Hammond and Christina Scull.

The widespread assumption since the announcement of the three-part Hobbit has been that Jackson and his fellow screenwriters would simply stretch out the action of the book. Yet that is clearly not what the trio is up to. In the press release, Jackson sounded much more enthusiastic:

Upon recently viewing a cut of the first film, and a chunk of the second, Fran Walsh, Philippa Boyens and I were very pleased with the way the story was coming together. We recognized that the richness of the story of The Hobbit, as well as some of the related material in the appendices of The Lord of the Rings, gave rise to a simple question: do we tell more of the tale? And the answer from our perspective as filmmakers and fans was an unreserved ‘yes.’ We know the strength of our cast and of the characters they have brought to life. We know creatively how compelling and engaging the story can be and—lastly, and most importantly—we know how much of the tale of Bilbo Baggins, the Dwarves of Erebor, the rise of the Necromancer, and the Battle of Dol Guldur would remain untold if we did not fully realize this complex and wonderful adventure.

There is a great deal of material in the appendices of LOTR relating to the plot of The Hobbit, though in many cases that material involves characters and events barely referred to in the novel. In the book, Gandalf departs from the Dwarves and Bilbo midway through, going off, as he later reveals briefly “to a great council of the white wizards, masters of lore and good magic; and that they had at last driven the Necromancer from his dark hold in the south of Mirkwood” (p. 357). All this was later fleshed out, partly in the body of LOTR and partly in its appendices: the council became The White Council, which included Elves like Galadriel and Elrond; the Necromancer gained a name, Sauron; his “dark hold” became his secondary dark tower, Dol Guldur.

As is quite clear from the trailers and from statements by the filmmakers, action involving the White Council and the attack on Dol Guldur will figure prominently in The Hobbit. Already an image of the White Council, including Saruman and apparently taking place at Rivendell, has surfaced in one of the licensed tie-in books:

This may not, however, be the White Council meeting that occurs during the action of The Hobbit. It may be a flashback to the one in Third Age 2851, described in the invaluable chronology of Appendix B:

2850 Gandalf again enters Dol Guldur, and discovers that its master is indeed Sauron, who is gathering all the Rings and seeking for news of the One, and of Isildur’s Heir. He finds Thráin and receives the key of Erebor. Thráin dies in Dol Goldur.

2851 The White Council meets. Gandalf urges an attack on Dol Guldur. Saruman overrules him. (p. 1088)

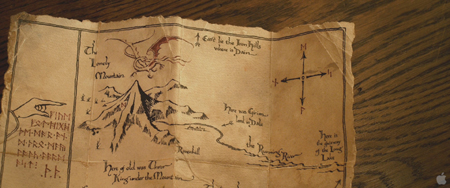

An image of Dol Guldur appears in the second trailer:

Saruman opposes the attack on Dol Guldur because he has secretly begun to search for the One Ring, desiring it for himself. Thráin gives Gandalf not only the key of Erebor but a map of it. That’s the map Gandalf looks at in Bag End just after his arrival in The Fellowship of the Ring. He will give the map and key to Thorin Oakenshield, son of Thráin and leader of the Dwarven troop in The Hobbit. Both will be crucial in the plot. The map also appears in the second trailer:

Tolkien wrote the appendices in 1954-55, vainly hoping to include them in the third volume of the novel. (They were incorporated into a later edition.) They retrospectively fill in events of the Third Age that led up to the plot of LOTR. He did not go back and extensively revise The Hobbit to incorporate these events, though he did a bit of fiddling with the original version in order to bring it more in line with LOTR. One cannot help but suspect that Tolkien wished he could have dealt with all these events in more than outline form. I for one am intrigued to see these bits of plot, sketched out by Tolkien in such a tantalizing way, fleshed out by the filmmakers.

No doubt that, as with LOTR, I will not agree with all the choices the screenwriters make in doing so. Still, we already have evidence that they can be adept in incorporating material from the appendices into the plot. They already did so to a more limited extent in LOTR. The scene in the extended DVD version of The Fellowship of the Ring of Aragorn visiting the grave of his mother, Gilraen, at Rivendell is derived from “Here Follows a Part of the Tale of Aragorn and Arwen,” a section of Appendix A (pp. 1057-1063). Tolkien considered this tale the most important part of the appendices, insisting that if foreign translations had to cut them, they should at least retain the narrative of the Aragorn-Arwen romance. The scene at Gilraen’s grave, brief though it is, adds depth to Aragorn’s character and to his relationship with his foster father, Elrond.

This moving story is also the source of the scene in The Two Towers where Elrond tries to persuade Arwen to leave Middle-earth for the Undying Lands by predicting her life with Aragorn. The dramatization of the prediction is a literal flashforward, for in the book Aragorn’s death eventually leads Arwen to regret her decision to remain with him, and she wanders, embittered and alone, in Lothlórien for a year before her own death (a period depicted by a single shot in the film). This flashforward is a powerful scene, and the film is all the better for its inclusion. We should not leap to the assumption that Jackson, Walsh, and Boyens will falter in their attempts to draw material from the appendices into The Hobbit.

There has been much fan speculation that the longer version of The Hobbit will include flashbacks to more of the Dwarves’ history. A scene might show the dragon Smaug driving the Dwarves from their ancestral home in the Lonely Mountain and assembling the hoard on which he lies when they return to retake the mountain. It might include their move into exile in the Blue Mountains west of the Shire. All of this could also be linked to Moria. Balin, whose tomb the Fellowship members discover in the Mines of Moria in The Fellowship of the Ring, is a character in The Hobbit, the eldest of the Dwarves. Between the action of The Hobbit and that of LOTR, he leads a troop of Dwarves to Moria to try and recapture it from the orcs that had conquered it generations earlier.

Tolkien wrote a brief history of the Dwarves and Khazad-dûm (Moria) in “Durin’s Folk,” another section of Appendix A. This includes an entire scene with dialogue, depicting Thráin’s father Thrór’s suicidal attempt to re-enter Moria; he is killed by the orc Azog. Although not crucial for the Quest of Erebor plot of The Hobbit, a flashback to such a scene would link it to the Moria passage of LOTR. There is a causal connection as well. Before departing for Moria, Thrór gives Thráin the last of the seven Dwarven rings, which leads Sauron to capture and imprison Thráin in Dol Guldur, taking the ring from him; that is why Gandalf later finds him in Sauron’s dungeons.

Such scenes might or might not be used, but the filmmakers have definitely decided to include Radagast the Brown, the third wizard, who is only mentioned in The Hobbit. (He appears in one scene in the LOTR novel, but he was eliminated from the film.) Radagast plays a limited role in Tolkien’s Legendarium, having apparently “gone rustic” and become absorbed with the birds and animals of Mirkwood, largely abandoning his part in trying to defeat Sauron. Still, his inclusion in the film seems a positive thing, as some charming shots of him playing with hedgehogs in the second trailer suggests:

The decision to divide The Hobbit into three parts presumably came too late to permit numerous changes in the first part. Nonetheless, the point at which the first film was planned to end has apparently been changed dramatically. The film’s official site posted an interactive wallpaper generator that showed a panoramic scroll summarizing the film’s scenes, from Gandalf scratching a rune on Bilbo’s door to the moment when the Dwarves and Bilbo escape from Thranduil’s dungeons in barrels floating down a river. That scene happens well over halfway through the novel. Once the three-part release was announced, the wallpaper generator was changed to its current version, which ends with the episode of Gandalf, the Dwarves, and Bilbo trapped up burning fir trees by wargs and goblins. Two shots from that episode are the latest events shown in the new trailer and would seem to provide a good cliff-hanger for the ending:

This episode happens in Chapter 6 of the book’s 19 chapters, while the barrels scene is in Chapter 9. This shift suggests that a considerable chunk of action has been added to the first film. That action probably derives from the LOTR appendices rather than some stretching of episodes from The Hobbit.

Perhaps to reassure fans, most of the new trailer shows scenes very familiar from the book: the Dwarves arriving unexpectedly at Bag End, the three trolls preparing to cook Bilbo (above), and of course the beginning of the famous riddling contest between Bilbo and Gollum. Two shots of Bilbo’s awestruck reaction to being in Rivendell (at the top) capture the spirit of the book perfectly. After all, Bilbo ended up living in Rivendell during his declining years, and while there he translated the ancient Elvish texts that became The Silmarillion. All this suggests that the bulk of the material derived from the appendices will appear in the second and third parts.

As a long-time Tolkien fan, I would be as disappointed as anyone if the decision to divide The Hobbit into three parts were done merely by stretching out the plot of the novel. All the evidence, however, points to a careful incorporation of bits of Tolkien’s own text to fill out the background of the tale and to link it more firmly to LOTR. Essentially it sounds as though the screenwriters have sought and probably found a way to incorporate the original “bridge” film, announced long ago when The Hobbit adaptation was first revealed in the press, into The Hobbit.

The bridge film was to have been a sequel to The Hobbit, which at that time was planned as a single film. It would fill in the events between the end of The Hobbit and the beginning of LOTR–a gap of sixty years in the novels. It apparently was to have been made up primarily of scraps of plot garnered from the appendices. Whether the writers would have been able to come up with an overall structure to unite those scraps is debatable. Using the strong spine of The Hobbit‘s plot to support them seems a promising solution to the problem.

Perhaps I will be disappointed upon seeing the film, but all the evidence so far indicates that the writers have been inventive and careful in expanding the project. Moreover, the trailers suggest that the technology used to create Gollum and to manipulate the sizes of the actors has improved since LOTR, as the frame below indicates.

Happy Hobbit Day to all!

For Tolkien’s thoughts on cutting versus compression for adaptations of his films, see The Letters of J. R. R. Tolkien, p. 261.

A man and his Focus

James Schamus on State Street, hailed by local livestock.

DB here:

“I wish,” one of my students said during a James Schamus visit to Madison back in the 1990s, “I could just download his brain.” Probably many have shared that wish. James is an award-winning screenwriter who has become a successful producer and head of a studio division, Focus Features (currently celebrating its tenth anniversary). No one knows more about how the US film industry works than James does. Yet he’s also deeply versed in the history and aesthetics of cinema. He teaches in Columbia’s film program, and his courses involve not filmmaking but film theory and analysis. How many people who can greenlight a picture have written an in-depth book on Dreyer’s Gertrud?

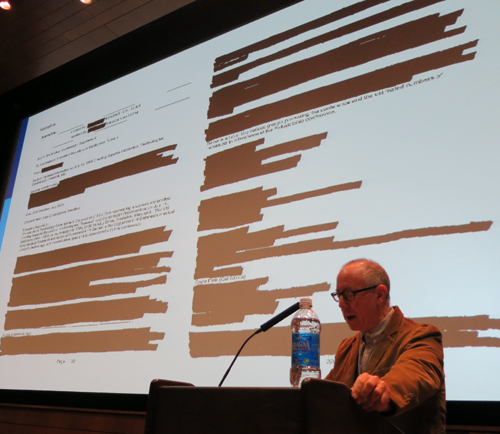

James came to campus last month for our Wisconsin Film Festival. His official event, sponsored by the University Center for the Humanities, was a talk called “My Wife Is a Terrorist: Lessons in Storytelling from the Department of Homeland Security.” That was quite an item in itself, tracing how James’ wife Nancy Kricorian discovered that she had a Homeland Security file. Pursuing that led him to broader meditations on digital surveillance in modern life. If he’s invited to present this in a venue near you, you’ll want to catch this provocative tutorial in how to read a redacted document.

While he was here, James spent a couple of hours in J. J. Murphy’s screenwriting seminar, and of course I had to be there. Herewith, some information and ideas from a sparkling session.

All battleships are gray in the dark

Hulk.

“This is not writing,” Schamus said. By that he meant that a screenplay isn’t parallel to a piece of creative writing, an autonomous work of art. Nobody ever walked out of a movie saying, “Bad film, but a great script.” In this he echoed Jean-Claude Carrière at the Screenwriting Research Network conference I visited back in September. A screenplay is “a description of the best film you can imagine.”

What sort of description? For certain directors, sparse indications are best. Collaborating with Ang Lee, Schamus knows he must under-write. Lee doesn’t want a movie that’s wholly on the page: “Ang wants to solve puzzles.” But for a studio project, the screenplay has to be airtight, since it functions as an insurance package for any director the producers hire. “A script has to be a battleship that no director can sink.”

James pointed out a bit of history. Back in the 1910s Thomas Ince rationalized studio production by using the script as the basis of all planning—budget, schedule, locations, and deployment of resources. The same happens today, with the Assistant Director breaking down the script for different phases and tasks of production. But on a studio project not everything is tidily planned in advance. Scripts can be rewritten during shooting or even later. Sometimes there are “parallel scripts”: stars can hire writers who spin out “production rewrites” to be thrust on the director. James, who has prepared the screenplay for Hulk and done his share of uncredited rewrites on other big films, speaks from experience.

Independent companies rely on screenplays too; Focus is writer-friendly. But in this zone of the industry, the writer needs to create a “community” around a script idea—a director or group of actors and craft people that support it. These are as valuable as a polished screenplay in getting a film funded.

What about the current conventions, like the three-act structure? James rejects the Syd Field formula. He thinks that the writer will spontaneously devise some intriguing incidents and arresting characters without recourse to beats, arcs, and plot points. “You can’t have half an hour go by without giving your characters something to do, or to shoot for.”

He also suggests that the writer’s second draft should be an exercise in rethinking the whole thing. “Don’t write your second draft from the first-draft file.” In your redraft, use flashbacks, play around with structure, or tell the action from a different point of view. This will engage you more deeply with the material and show you possibilities you hadn’t imagined. In terms I’ve floated in various places: take the same story world, but recast the plot structure or the film’s moment-by-moment flow of information (that is, its narration). Or try choosing a different genre. For The Wedding Banquet, James turned the original script, a melodrama, into a situation derived from screwball comedy.

Down in the mosh pit

Jim Carrey in Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind.

James has been both an independent producer, in partnership with Ted Hope at Good Machine during the 1990s, and a specialty-division producer with Universal for Focus. The moment of passage for him came when, rewriting Ang Lee’s first feature, Pushing Hands, James realized that he had to get the whole project in shape for filming. After that, and The Wedding Banquet and Eat Drink Man Woman, producing followed naturally.

When James started, a single person could cover most producer duties on an indie film, but now it’s very difficult. Finding material, gathering money, signing talent, checking on principal photography and post-production, planning marketing and distribution across many platforms, tracking payments after release—it’s all a daunting task for one individual. Today an indie movie may list seven to twenty producers. Some probably helped by finding money, some worked especially hard to get material, and a few just slept with somebody.

A traditional producer’s job is to keep the budget under control. Today, with digital filming making special effects cheaper, screenwriters and directors think naturally of more elaborate visuals. This can work with something like Take Shelter, James suggested, but on the whole he thinks that directors shouldn’t jump to extremes. He recalled that using “handcrafted effects” cut the original budget of Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind by a third, and that led to more unusual creative results, like outsize sets and in-camera trickery.

The “independent cinema” scene has always been quite varied. Again James had recourse to history: in the 1960s both United Artists and Roger Corman were labeled independents. The artier independent side developed through the infusion of foreign money and new technology. From the 1970s onward, overseas public-television channels invested in US films by Jarmusch and others, while cable and home video needed product and so financed or bought indie projects. The video distributor Vestron, for instance, could not acquire studio films, so, armed with half a billion dollars, the company began generating its own content. In the same era, pornography was shot on 35mm, and many crafts people learned in that venue and transferred their skills to independent cinema.

Today, however, the indie market is both more fragmented and more fluid. The spectrum space between tentpole Hollywood and DIY indies is being filled by net platforms and cable television. James pointed to the ease with which Lena Dunham moved from Tiny Furniture to the HBO series Girls. Downloading and streaming add to the churn. IFC and Magnolia distribute films, but these companies are owned by cable channels and hold theatrical venues as well. They acquire scores of new films a year, using theatrical releases to get reviews that can support VOD and DVD. Focus can tier its marketing in similar ways, using DVD and VOD outlets to lead viewers to content online under the rubric Focus World.

These new “paramarkets,” James suggests, are porous, overlapping, and still evolving. Traditional windows, he says, have become a mosh pit.

James had a lot more to say, and I expect to be referencing more of his ideas on VOD in a blog to come. But this gives you a taste of the energy and breadth of his thinking. He’s constantly busy but never less than enthusiastic and generous. He always has time to share ideas about anything, from politics to cinephilia. The most exhilarating thing about talking with him is that you know more excellent work lies ahead.

Apart from titles I’ve already mentioned, James Schamus’ screenplays include The Ice Storm, Ride with the Devil, Taking Woodstock, Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, and Lust, Caution, Films that he produced and/or distributed include Poison, The Brothers McMullen, Safe, Walking and Talking, Happiness, The Pianist, 21 Grams, Lost in Translation, Shaun of the Dead, A Serious Man, Coraline, Brokeback Mountain, The Motorcycle Diaries, Eastern Promises, Atonement, Reservation Road, In Bruges, Milk, Sin Nombre, Greenberg, The Kids Are All Right, The Debt, Pariah, Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy…and plenty more.

Schamus provides a video review of the top ten Focus titles chosen by viewers for the company’s anniversary.

J. J. Murphy blogs about screenwriting, the avant-garde, and independent film here. His most recent book is The Black Hole of the Camera: The Films of Andy Warhol.

More on the concepts of story world, plot structure, and narration can be found in “Three Dimensions of Film Narrative,” in my book Poetics of Cinema. A brief account is here.

James Schamus lecturing, University of Wisconsin–Madison Center for the Humanities, 19 April 2012.

TINKER TAILOR: A guide for the perplexed

Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy.

DB here:

As the final credits rolled, a man behind me blurted out, “I don’t get it.” He’s not alone. Kristin and some acquaintances have told me that they found parts of Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy hard to follow. Several critics, while praising the film (and doubtless getting more of it than that guy), have warned viewers to pay close attention. Roger Ebert said:

I enjoyed the film’s look and feel, the perfectly modulated performances, and the whole tawdry world of spy and counterspy, which must be among the world’s most dispiriting occupations. But I became increasingly aware that I didn’t always follow all the allusions and connections.

Some of the film’s admirers advise us not to worry much about the intricate storyline. Michael Phillips remarks:

This is one of the finest achievements of the year, and while it’s easy to lose your way in the labyrinth, I don’t think “Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy” is most interesting for its narrative pretzels. Rather, it’s about what this sort of life does to the average human soul.

Even if I weren’t a le Carré fan, I’d be fascinated by a film that can succeed both critically and financially and still leave its audience puzzled about its plot.

Critics of popular filmmaking claim that our movies cater to simple minds, but we actually find a lot of successful films, from Groundhog Day and Pulp Fiction to Inception, that are complex in intriguing ways. I argued in The Way Hollywood Tells It that since the 1960s one current of filmmaking has explored narrative strategies that were minor, even unheard-of, options in earlier times.

I’m not ready to join Steven Johnson in suggesting that audiences have become smarter. In certain respects older films are more demanding than contemporary ones. I’d rather say that new conventions are in force, aimed at certain sectors of the audience who are willing to put forth the effort. Ambitious filmmakers may find new ways to fulfill these conventions, balancing novelty with intelligibility. This is the path, I think, that the makers of Tinker Tailor took, and it didn’t prevent the film from earning $17 million at the US box office.

The film’s ’70s patina isn’t off-putting. The filmmakers offer deliberately grainy imagery, enveloped in hazes of rain and cigarette smoke. The palette, except for Ricki Tarr’s idyll with Irina, is grey, brown, and beige. Scenes are shot with long lenses, rack-focus, and drifting tracking shots. Zooms and push-ins are interrupted by cutaways. The result is an Altmanesque look, but more disciplined. It’s not the visual style, then, but those the narrative pretzels—another reminder of late ‘60s and early ‘70s storytelling—that attract my notice today.

So I persist: What makes the movie hard to grasp? If we can get a sense of this, we might get to know Tinker Tailor more intimately, while also producing some ideas about how mainstream films work generally. To attempt an answer, I have to go into detail. I won’t be supplying a plot synopsis, but the Wikipedia entry is reasonably comprehensive. I’ll be looking less at the story and more at the storytelling. Still, don’t read further if you haven’t seen the film. In the tradecraft jargon of blogging: There are spoilers ahead.

Breaking up the blocks

One factor contributing to the film’s difficulties, as many reviewers have pointed out, is that it’s adapted from a big and complex book. But it isn’t just the size of the original novel that poses problems. It’s the way the plot is constructed and the story is narrated.

The plot of the novel Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy (published 1974; the commas aren’t in the adaptations) consists mostly of blocks of flashbacks. The action starts long after Control has died and his old staff, including George Smiley, has retired. The novel’s first scenes show Jim Prideaux’s arrival at the boy’s school, seen from the perspective of Bill Roach, his shy confidant. We don’t yet know how Jim connects to Smiley, who after a dinner with a gossipy acquaintance, is summoned to investigate the prospect of a mole in the Circus’s top echelon.

Smiley’s investigation involves questioning witnesses like Connie Sachs, but more often it involves “burrowing,” working patiently through the files that Control had studied. Le Carré presents what Smiley gleans from the files as flashbacks, and interwoven with those are Smiley’s reflections on the key personnel and their power struggles. Institutional memory and Smiley’s rueful recollections tie together the ambush of Jim Prideaux and the vein of top-secret information code-named Witchcraft.

Respecting the novel’s construction would demand a cascade of long tales framed by Smiley’s step-by-step pursuit. Arthur Hopcraft’s screenplay for the seven-installment 1979 BBC series took the simpler option of starting with a scene that is presented very late in the novel, during Jim’s revelatory confession to Smiley. The TV series opens with Control summoning Jim and sending him off to Czechoslovakia. Jim is shot and Control is cast out. Clarifying the string of events this way, and giving us a decent action scene early on, has its cost: Smiley doesn’t enter the series for twenty-three minutes.

Since Hopcraft and director John Irwin had hours at their disposal, the scenes could stretch and breathe, and they retain the somewhat chunky, modular quality of the novel. But a two-hour film couldn’t handle the book’s plot so spaciously. What did the team of Bridget O’Connor and Peter Straughan do? Straughan explains:

The adaptation process differs from book to book, but in the case of “Tinker Tailor,” it involved a kind of mosaic work. The structure of the novel was broken into pieces. Some long sequences would remain intact – Peter Guillam stealing the files from the Circus, for example – but in other cases we would take a line or event from one place in the narrative and move it elsewhere, shifting the fragments around endlessly until it felt right. The goal was to create a new version of the narrative which would bear a close family resemblance to the source material, but have its own cinematic personality. The really difficult part was not fitting the plot into two hours but doing it without losing the tone; to give the film the same autumnal, melancholy pace, and to give the script air and silence.

The most obvious instance of this fragmentation is the repetition of the ambush of Bill Prideaux in the Budapest café. In keeping with current norms of storytelling, this scene is replayed at crucial points, each time giving us a bit more information relevant to the scenes of testimony around it.

Repetition is a luxury that can’t be overindulged in adapting a hefty novel. To spare time for the pace, the air, and the silences the filmmakers want to include, they had to be more concise in their presentation of plot. They had to chop le Carré’s big narrative blocks into bits.

When we view a mosaic we can step back to see how the composition blends all the fragments. But we have to experience a movie bit by bit. A film, we might say, is a moving mosaic, and we are usually standing very close to it. Just as important, a mosaic, made out of gaps, leaves it to us to grasp how the parts fit together—to make our mind jump the gaps.

Unconventionally conventional

How does Tinker Tailor fit the pieces together? In general, the film adheres to common conventions of modern storytelling but then subtracts one or two layers of redundancy. The little gaps created make the film seem roundabout today, when rather linear and explicit narration is the norm.

Start with a simple case. Like many modern spy films, Tinker Tailor initiates a shift to another locale by a long-shot framing, often from on high. Here’s an example from The Bourne Ultimatum.

It’s triply redundant: We see a city landscape including the Arc de Triomphe; we’re told it’s Paris; and we’re told it’s Paris, France (not Paris, Maine). Compare the parallel shot from Tinker Tailor.

Not exactly a difficult leap—who doesn’t know that the Eiffel Tower is in Paris (France)?—but it’s a little less explicit. Earlier instances are more laconic. When we’re taken to Budapest and Istanbul, probably not as immediately recognizable to many in the audience as Paris, we get a cityscape with only one mention in the dialogue to tag the setting, and no captions. Least explicit of all are the shots picking out the Circus in London.

Another film would have typed out, “MI6 HQ,” but we’re left to infer that behind this façade the Secret Intelligence Service does its work. So the convention of the exterior establishing shot is respected but made a little less redundant.

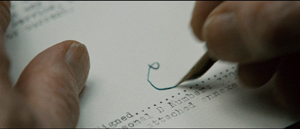

Consider as well the introduction of the Circus’s decision makers. Another film might have started with Smiley and followed him from his office into the briefing room. Instead, he’s introduced as one of several men, then as an out-of-focus figure alongside Control. And even Control could have been more clearly identified. He signs his resignation with what could become an emblem of the film’s stingy approach to storytelling.

Just as truculent is the process by which Lacon is led to summon Smiley. First Lacon gets a warning call from the field agent Ricki Tarr. So far, so conventional. But Tomas Alfredson has staged things so that Tarr is seen at a distance, turned from us, and blocked by a phone booth. Who is this guy? We must get all our information solely from his voice, not his facial expression.

Soon after Peter Guillam has entered the Circus, he gets a call. Most directors would have cut away to the caller, or at least let us hear what Peter is hearing. But we’re denied that information. On the soundtrack, we hear only a muffled, “It’s Oliver…ringing…” It’s Lacon, but you know that only if you know his first name is Oliver, and we’re teased by hearing almost nothing of what he’s saying. We know even less than Guillam, and this suppressive narration is characteristic of Alfredson’s handling of genre conventions.

Next we see Smiley at home, watching television. There’s a knock at the door. Cut to a car driving, Peter at the wheel and Smiley in the back seat. Smiley is silent, and Peter offers his regrets: “I was sorry to hear about Control, Mr. Smiley.” Earlier we’ve been given one shot of the dead Control in the hospital. So much for his backstory.

Finally, as the car pulls up at Lacon’s house, the fragments combine into an intelligible sequence when Peter says, “He said Tarr called him from a phone box.” Retrospectively, we can buckle the sequence up as a familiar genre action: The hero is called back to the battle by his chief.

Another convention, one that goes far back, is the dialogue hook. This is a bit of speech that ends one scene and links directly to the next one. Tarr calls Lacon and names Guillam as his supervisor. Cut to Guillam crossing the street and entering the Circus. Later, Smiley suggests that he and Guillam investigate Control’s flat. Cut to them entering it.

Dialogue hooks, as I’ve traced out here, are enormously helpful in guiding us through the plot. But sometimes Tinker Tailor works more obliquely. In one scene Peter reads of the staff who were sacked following Control’s fall. One is Jerry Westerby, whom we’ll meet a long while later, and the other is Connie Sachs. Cut to a train station, with Smiley buying a ticket to Oxford. It’s a hidden hook: most films would include in the earlier scene a line such as, “Connie Sachs, who’s now in Oxford.” Again, a conventional device is roughened a bit, made slightly more difficult. And sometimes the hook is visual and disruptive, as when a shot of Jim, bleeding in the Budapest arcade, is followed by a shot of the boy Bill Roach looking out a window at Jim’s arrival, as if he’s also looking down at his future teacher.

The BBC series was broadcast in weekly episodes, so recapping and backtracking in each installment helped viewers remember. At intervals we see Smiley bringing Peter up to date and briefing Lacon on current discoveries. The film flagrantly refuses to provide this conventional help. As Ebert notes:

More ordinary spy movies provide helpful scenes in which characters brief each other as a device to keep the audience oriented. I have every confidence that in this film, every piece of information is there and flawlessly meshes, but I can’t say so for sure. . . .

What replaces the standard briefing scenes? Some rather elliptical passages. There are the nodes in which Smiley reflects on the evidence. We get a shot of him staring, followed by a cascade of imagery as his mind plays with possible suspects.

Linked to the briefing scene is another convention, the board or wall on which all the suspects are diagrammatically arranged. In our visit to Control’s apartment we might have seen pictures of Bill Haydon, Roy Bland, Toby Esterhase, and Percy Alleline laid out in a rectangle, with the sinister silhouette of Karla up top, and dotted lines connecting them. Yet Control, the bedraggled chainsmoker, could hardly be so tidy. Instead, the film gives us something more in character and more oblique: a litter of chessmen, each with a picture taped awkwardly on. Eventually Karla is revealed as another piece (the powerful white Queen). On his own, Smiley joins in Control’s conceit and tapes a picture of the new suspect Polyakov to a bishop.

Le Carré’s novel tied the suspects together with a verbal emblem, based on the child’s nursery rhyme. It linked the boy’s school to the Circus. But the film doesn’t introduce the tinker-tailor motif until very late. Instead the chess pieces visualize the multiple-choice problem, but in a ragged, haphazard way that suggests that perhaps Control really was, as Jim Prideaux suspects, going mad. More broadly, the imagery (with the briefing room as a gridded checkerboard) reminds us that spying, known for decades as The Great Game, is now a global chess match. It pits Karla against Smiley—whom Control has identified as the black Queen.

George the Obscure

Again and again, the script and Alfredson’s direction invoke a convention only to make it more difficult to grasp. The central examples involve Ann, the faithless wife. She isn’t just treated elliptically; she’s suppressed. Instead of showing her flirting with Bill at the Christmas party, we see only the back of her head and Bill looking past Smiley’s shoulder.

In a later flashback to the party, Smiley looks out the window and sees Ann in the garden. Another film would have shown us who’s clutching her in the foliage, but this film leaves it to us.

Of course many viewers will know Ann’s partner is Bill, but another film would have confirmed this more explicitly. Instead another standard scene is handled in a glancing way. More generally, Ann’s phantom presence not only makes her seem remote, like a princess in a tower, but sets her off against the blonde Irina, the maiden to be rescued in Ricki Tarr’s story. Thanks to the camera and a compact mirror, Irina’s face gets the caresses another film would devote to Ann.

Irina, beautiful and sincere, holds the film’s major secret, the one that initiates Smiley’s investigation. She harks back to the blonde mother who is in the line of fire in the Budapest arcade, and that shooting prefigures Irina’s fate.

The crowning achievement in the film’s laconic way with conventions is the climax in the safe house. Smiley has arranged for Ricki to send a message that will force Karla’s mole to make an emergency appointment with his connection Polyakov. There Smiley, Guillam, and Mandel will record the meeting and capture the double agent. In the BBC series, this climax runs over eight minutes, built out of crosscutting and suspenseful waiting. Smiley and Guillam burst in together and a quick pan shot reveals Bill as the culprit.

The film uses suspense and crosscutting as well, but the sequence consumes only six minutes. More important, by switching our attachment away from Smiley at the crucial moment, it conceals his entry to Bill and Polyakov. Instead we follow Guillam separately into the house, up the stairs, and to the parlor. There he confronts the aftermath of what might have been a heroic confrontation. Climax is treated as anticlimax.

Jim Emerson, in a nicely honed piece, suggests that we think of such passages as not so much elliptical as economical. I want to have it both ways. The scenes are economical because they fulfill familiar narrative and genre-based functions: We know how to fill them in. Yet they’re also elliptical because they hold back information, sometimes a little and sometimes a lot. A mosaic can show us familiar people and things, but it also asks us to make extra effort to see the pattern emerge. The tesserae fit, but the bumps and grooves between them are palpable.

It may be that art films have always tended to be self-consciously wrought genre films. L’Avventura: A mystery-melodrama. Blow-Up: A detective story. Drive: the thinking person’s action film. If so, then Tinker Tailor is the smart Bourne movie. Creative novelty needs a familiar base to play off. Movies come from other movies, and originality can take a tradition, even a popular one, as a point of departure for innovation.

Best watcher in the unit

Once plot gaps have alerted us, we should expect things to proceed through hints. Granted, there are hints that can’t be picked up unless you know the novel. For instance, the film doesn’t stress the fact, emphasized in the novel, that Bill is an amateur painter and the canvas he brings Ann on the fateful night is one of his own works. It’s the picture that Smiley is studying at the end of the credits sequence, as if the film’s two primary antagonists are already squaring off.

But, sticking just to the hints we can pick up without the novel, the film is fairly rich. It invites multiple viewings, as many movies do nowadays, in order to catch the undercurrents or the things that flash by too quickly on the first pass. (If we want to find more, we can buy the DVD.) I can’t pretend to exhaust the possibilities, but here are some that strike me.

Go back to those chessmen. As we’ve seen, the two antagonists, Karla and Smiley, are made parallel as the rival Queens. Three suspects are assigned to innocuous pieces: Percy as the white Rook, Toby as the black Knight, and Roy as the black King (although that assignment might be a narrative feint, hinting that Roy’s the traitor). But Bill is the white Bishop, and in retrospect we can see the fact that Smiley makes the Moscow agent Polyakov a black Bishop is a pointer to Bill’s guilt—and maybe a suggestion that, as Bill will say, George knew all along.

Or take the homosexual element. One question that comes up in conversation after the movie is whether Bill and Jim were lovers. It’s treated as a possibility in the original novel and becomes stronger as the film proceeds, especially after Bill—in a moment of privileged information for the audience—pockets a picture of the two friends embracing and laughing. By the end, in the final flashback of the Christmas party, Bill rouses the loner Jim and flashes him a smile; but the brandy glass he floats away with seems intended for Ann. Bill’s bisexuality is explicit in the epilogue when, in the compound, he asks Smiley to pay off both a girl and a boy. More than a hint, as well, is the tear that dribbles down Jim’s cheek as he executes his friend. (Bill’s wound, rhyming with Jim’s perforated back in Budapest, again recalls the slain mother in the arcade.)

Similarly ambivalent is the presentation of the dapper Peter Guillam. He’s introduced turning his head to watch a cute young lady pass. Later he’s revealed to be gay: for security reasons, he has to break up with his partner. In retrospect, we can see the shot when Bill and Peter eye the new clerk Belinda as presenting two double agents, each one passing as a lady-killer.

More minor touches hint at the sexual undercurrent. Bill on the phone: “And I said you may fuck me but you still have to call me sir in the morning.” It takes a quick eye to spot another manifestation of the motif. Polyakov, posing as a cultural attaché, writes articles for a bilingual magazine. After Connie has told her tale, there’s an insert—an excerpt from Connie’s memorabilia, or perhaps only a memory of Smiley’s—of an article signed by Polyakov, which says of the Russian Ballet corps:

To see them only in a narrative ballet would be to know them incompletely. The programme shows a perfect cross section of their accomplishments.

They can dazzle us with a technique that seems to defy the laws of gravity but that is not merely acrobatic because it is truly gay in expression.