Archive for the 'National cinemas: Iran' Category

Venice, virtually

Careless Crime (2020)

Every September over the last three years, we’ve immensely enjoyed visiting the Venice International Film Festival. There David has participated in the Biennale College Cinema discussions with stimulating colleagues.

This year, alas, the coronavirus kept us home. But the festival did make available a selection of fourteen films online. Each could be viewed for five days at the very fair price of $6 per film. (Here is the array of choices. A few are still available, so hurry.)

We took advantage of this opportunity and watched several titles. Here are our thoughts about three of them. (The first section is by David, the second by Kristin.) We hope that if you get a chance to see them on the big screen or at home you’ll investigate.

GOFAC is back! Actually, it never went away

The Art of Return (2020).

Back in the late ’70s and early ’80s, I tried to analyze the conventions governing a certain approach to moviemaking, the one that’s come to be called “art cinema.” My examples were films by Fellini, Antonioni, Bergman, the French New Wave, and many of their contemporaries.

In the years afterward, I revisited the ideas and asked: Are these conventions still in force? My conclusion in an updated version of the essay in Poetics of Cinema (2008) was: yes. From Fassbinder to Wong Kar-wai, from Distant Voice, Still Lives (1988) to Maborosi (1995) and beyond, we can find art-cinema principles of storytelling and style. In that book, the extended example was Varda’s Vagabond (Sans toit ni loi, 1985), while other chapters traced how this tradition mobilized new options like forking-path narratives (e.g., Run Lola Run, 1998) and network narratives (e.g., Les Passagers, 1999). There’s a pirated pdf of the updated essay here.

Since then, it’s been fascinating to watch a younger generation of filmmakers take up this tradition. Every festival I visit furnishes examples, as you can see from our entries on this site. I had the same sense when watching Pedro Collantes’ The Art of Return (El Arte de Volver) and Christos Nikous’ Apples (Mila). Good Old-Fashioned Art Cinema is still with us.

The Art of Return is centered on Noemi, who returns to Madrid after six years in New York. She has come home to audition for a role in a telenovela, and in the course of twenty-four hours she encounters several people from her past. The film consists of a series of duologues, as Noemi visits her dying grandfather, quarrels mildly with her sister, reconnects with her actor friend Carlos, and learns through another friend what became of Alberto, her ex.

What makes The Art of Return a prototypical art film is the way sheer chronology replaces a strongly causal plot. Apart from attending her audition, Noemi doesn’t have a strong goal; she drifts from one encounter to another. Most of these long scenes are devoted to discussions of her past, with hints about why she left Spain, as well as reactions of others to her personality. The task for a filmmaker using this episodic structure is to create patterns of revelation for us and for the character.

We need backstory about Noemi, and Collantes shrewdly avoids supplying flashbacks that would supply that. Instead, her past is refracted through the reactions of characters who are reconnecting with her, after much that has happened in their own lives. Gradually we assemble a fragmentary sense of what impelled her to go to New York. This revelation of the past is in effect the “under-plot” of the action.

Along with this pattern of revelation for us there are revelations for Noemi herself. She learns about her friend Ana’s floundering artistic ambitions, about her ex Alberto, about Carlos’ judgments of her. In an art film, the keenest revelation for the protagonist comes through an epiphany, a moment in which the character–sometimes mysteriously–gains self-awareness.

The crucial epiphany in The Art of Return, I think, occurs in a quiet scene in the park, among the trees that Noemi feels have been sculpted by a mystical force. By chance–again–she sees something that gives her the strength to make a decision. Yet in a typical art-cinema move, the outcome of that decision is withheld from us, suspended in a shot reminiscent of The 400 Blows (1959).

Collantes skillfully creates a firm pattern, with the opening scene symmetrically balanced by the final audition. In between, as in La Dolce Vita (1960) and Angela Schanelec’s Passing Summer (2000), the protagonist’s encounters provide a sampling and survey of life in the city, from the bohemian artists to the Romanian migrant community. A College selection, The Art of Return has already been acquired for theatrical distribution in Spain and other territories.

Apples (2020).

Because the art-cinema tradition minimizes a goal-directed plot, it often creates patterning through routine actions that are modified across the film. The changes in the routines reveal changes in a character or a situation. A vivid example is given in the Greek film Apples. After we’ve seen our protagonist regularly buy and eat apples (lots of ’em), he learns from a grocer that apples sharpen memory. He immediately switches to oranges. What psychology can justify this strange piece of behavior?

We understand it completely, because what has gone before has created a compelling context. The era is vaguely pre-digital, though there are some anachronisms. In the midst of an epidemic of amnesia, the poker-faced Aris is taken to a clinic for memory recovery. His doctors have created an experimental technique to give him a new life by reenacting routines of childhood, adolescence, and young manhood. As he rides a bike, fishes in a stream, visits a costume party, and goes to a dance club, he records his actions on Polaroids. These will fill an album and serve as replacement memories.

So Aris has a goal, albeit a diffuse one. We haven’t been told his overall program, so we are left to slowly figure out the rationale behind his dressing up as an astronaut or getting a lap dance. The film’s narration is almost as laconic as its protagonist, although a couple of scenes with his doctors show some sardonic humor. They eat his cooking and ignore the pathos of his situation while also, probably, misdiagnosing him.

Crucially, his retraining regimen intersects with that of another amnesiac, a woman further along in the program. Their relationship gives the film a romantic subplot, as well as its two most exuberant scenes: a dance to “Let’s Twist Again,” in which Siri seems to suddenly recover muscle memory, and a drive that spurs him to sing along with “Sealed with a Kiss.” (Hints about the under-plot give these scenes a dose of mystery and ambiguity–two more appeals of art-cinema storytelling.) All of this takes place before the apples-to-oranges shift, which in this context becomes as dramatic a twist as one would find in a thriller.

Shot and paced with extraordinary rigor in the 4:3 format, Apples is a perfect example of how GOFAC can create a distinct blend of curiosity, surprise, humor, and suspense. The film’s revelations in the final stretch are carried out as unemphatically as everything else, lending the character’s secrets an austere dignity. Apples has been eagerly acquired for many territories, and the director, who worked with Yorgos Lanthimos on Dogtooth, is preparing an English-language project. It will be, he hopes, “more accessible/mainstream.” Not entirely, I hope.

A carefully artful Iranian film

Careless Crime (2020).

Back in 2014, we were introduced to the strange world of Iranian director Shahram Mokri with his second feature, Fish and Cat. It’s a 139-minute single-take movie with a twisty plot in which the camera runs into separate groups of people in a rural lake area, with events starting to repeat from different points of view as the camera circles back on its route. We saw it in Vancouver, but it had premiered in the Orrizonti program at the Venice International Film Festival in 2013; it won a special prize “For Innovative Content.”

This year Mokri was back in the Horizonti thread with his third feature, Careless Crime. This time Mokri didn’t win a Festival prize, but the film received a FIPRESCI award for Best Screenplay.

Careless Crime is even trickier than Fish and Cat. It’s one of those puzzling films that requires the spectator to figure out the time frames of the different plot threads–and indeed how many times frames there are–and keep track of many characters. It’s a bit like Lazlo Nemes’ Sunset in the way it demands that the viewer constantly keep on the alert for the most fleeting or oblique clues as to what’s going on. (It’s interesting that Nemes and Mokri both have a penchant for lengthy tracking shots following a character closely from behind, as in the frame above.) Apples is another film that provides only a few subtle clues abut a major plot premise that eventually provides a twist at the end

There are two major plotlines. A group of four scruffy men plan to set fire to a crowded cinema as a political protest. Their actions recall an actual event that was the inspiration for the story. In 1978 a group of four arsonists set fire to the Cinema Rex in Abadan, causing the deaths of over 400 people because the exits were blocked.The event is credited with having launched the Iranian Revolution of 1979.

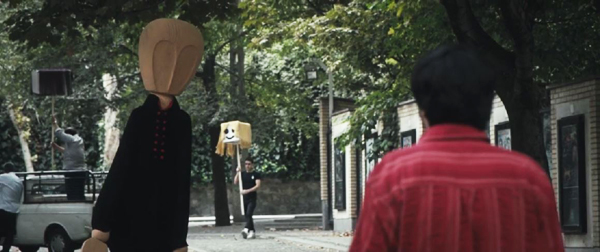

We follow the four men as they carry out inept preparations for their attack on the cinema. The group includes Faraj, a sad-sack who spends much of the early part of the film trying to get the nerve pills to which he is addicted. He tracks down a dealer who happens to be an employee at the local cinema museum and who is dressed in a large puppet costume, from the depths of which he digs out the precious bottle for Faraj.

The second plot involves a small, equally inept group of soldiers who have been sent to deal with an apparently unexploded missile deep in the countryside (see top). Contradictory information suggests that the missile landed some time ago and has been defused or that it landed the day before and needs urgent attention. Instead the men wander up into a local tourist area where two college girls are setting up an outdoor screening of the classic 1974 Iranian film, The Deer. This happens to be the film that had been screening at the Cinema Rex when the 1978 arson attack occurred. But the soldiers neglect their duty to solve the missile problem and spend their time waiting to see the young women’s film to find out if they are up to something nefarious. Thus two “careless crimes” may be involved. The the relationship between the two plotlines only becomes apparent late in the film.

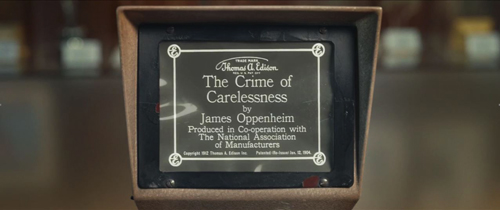

An obsession with cinema runs through both plots. The cinema targeted by the terrorists is apparently attached to the nearby museum and shows mostly art films, as is suggested by the posters for classic films that decorate the lobby. Young patrons and supporters of the cinema who hang around waiting for the show to start mention repeatedly that a friend has written an essay on The Deer, and we glimpse a poster for Kiarostami’s Close-Up. At one point Faraj, seeking the drug-dealer at the museum, sees a vintage film playing on an editing table.

It’s a 1912 Edison film, The Crime of Carelessness, in which poor safety conditions and a carelessly dropped cigarette led to a disastrous mill fire. At the end, a title in Farsi comes up, describing not the action of the silent film just shown but the 1978 Cinema Rex fire.

As all this suggests, there’s a good deal of magical realism in Careless Crime. At one point a single long take meanders around the open-air setting for the girls’ screening, picking up the same actions and dialogue repeated from different angles. During Faraj’s search for the drug-dealer, a museum employee guides him through the museum and its basement, again all in a single moving take. The seemingly endless basement is shot entirely against a black background, though at one point images of the two seemingly accompany them in the background.

Despite the grim subject matter, as in Fish and Cat, there is a good deal of self-conscious humor in Careless Crime. Little jokes are made about movies, and especially arty ones, as when a minor couple in the targeted cinema waits for the film to start. The woman looks at the screen (perhaps at a trailer?) and remarks, “I hate any film that has this laurel sign on it.” The reference is to one of the primary institutions of the international art cinema:

Is Mokri twitting the festival for not having chosen to show his films? As is now clear, his film’s repeat presence at Venice turned out to be an advantage in the long run. Although Careless Crime did not win a prize in the Horizonti competition, outside the official festival it received the FIPRESCI award for the best screenplay. Perhaps, when it finally becomes possible to return to the VIFF in person, we will see the next Mokri film and struggle not to be puzzled.

Thanks, as ever, to Alberto Barbera, Paolo Lughi, Savina Neirotti, Peter Cowie, and Michela Lazzarin for their assistance this year and in the past.

You can watch an extract of the Biennale press conference for Apples. The director discusses it in this Variety interview.

Our earlier entries on the Venice festival are here.

Apples (2020).

Stuck inside these four walls: Chamber cinema for a plague year

The Bitter Tears of Petra von Kant (1972).

Privacy is the seat of Contemplation, though sometimes made the recluse of Tentation… Be you in your Chambers or priuate Closets; be you retired from the eyes of men; thinke how the eyes of God are on you. Doe not say, the walls encompasse mee, darknesse o’re-shadowes mee, the Curtaine of night secures me… doe nothing priuately, which you would not doe publickly. There is no retire from the eyes of God.

Richard Brathwaite, The English Gentlewoman (1631)

DB here:

We’re in the midst of a wondrous national experiment: What will Americans do without sports? Movies come to fill the void, and websites teem with recommendations for lockdown viewing. Among them are movies about pandemics, about personal relationships, and of course about all those vistas, urban or rural, that we can no longer visit in person. (“Craving Wide Open Spaces? Watch a Western.”)

Cinema loves to span spaces. Filmmakers have long celebrated the medium’s power to take us anywhere. So it’s natural, in a time of enforced hermitage, for people to long for Westerns, sword and sandal epics, and other genres that evoke grandeur.

But we’re now forced to pay more attention to more scaled-down surroundings. We’re scrutinizing our rooms and corridors and closets. We’re scrubbing the surfaces we bustle past every day. This new alertness to our immediate surroundings may sensitize us to a kind of cinema turned resolutely inward.

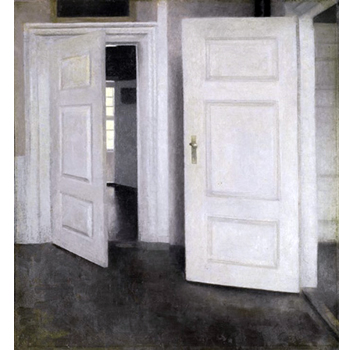

Long ago, when I was writing a book on Carl Dreyer, I was struck by a cross-media tradition that explored what you could express through purified interiors. I called it “chamber art.” In Western painting you can trace it back to Dutch genre works (supremely, Vermeer). It persisted through centuries, notably in Dreyer’s countryman Vilhelm Hammershøi (below).

Plays were often set in single rooms, of course, but the confinement was made especially salient by Strindberg, who even designed an intimate auditorium. For cinema, the major development was the Kammerspielfilm, as exemplified in Hintertreppe (1921), Scherben (1921), Sylvester (1924), and other silent German classics. Kristin and I talk about this trend here and here.

In the book I argued that Dreyer developed a “chamber cinema,” in piecemeal form, in his first features before eventually committing to it in Mikael (1924) and The Master of the House (1925). Two People (1945) is the purest case in the Dreyer oeuvre: A couple faces a crisis in their marriage over the course of a few hours in their apartment. (Unfortunately, it doesn’t seem available with English subtitles.) But you can see, thanks to Criterion, how spatial dynamics formed a powerful premise of his later masterpieces Vampyr (1932), Day of Wrath (1943), Ordet (1955), and Gertrud (1964).

Dreyer wasn’t alone. Ozu tried out the format in That Night’s Wife (1930), swaddling a husband, wife, child, and detective in a clutter of dripping laundry and American movie posters.

Bergman exploited the premise too, in films like Brink of Life (1958), Waiting Women (1952), his 1961-1963 trilogy, and Persona (1966). (All can be streamed on Criterion.)

Chamber cinema became an important, if rare expressive option for many filmmaking traditions. Writers and directors set themselves a crisp problem–how to tell a story under such constraints?

The challenge is finding “infinite riches in a little room.” How? Well, you can exploit the spatial restrictiveness by confining us to what the inhabitants of the space know. Limiting story information can build curiosity, suspense, and surprise. You can also create a kind of mundane superrealism that charges everyday objects with new force.

On the other hand, you need to maintain variety by strategies of drama and stylistic handling. Chamber cinema–wherever it turns up–offers some unique filmic effects, and maybe sheltering in place is a good time to sample it.

Herewith a by no means comprehensive list of some interesting cinematic chamber pieces. For each title, I link to streaming services supplying it.

Bottles of different sizes

From David Koepp I learned that screenwriters call confined-space movies “bottle” plots. There’s a tacit rule: The audience understands that by and large the action won’t stray from a single defined interior. In a commentary track for the “Blowback” episode of the (excellent) TV show Justified, Graham Yost and Ben Cavell discuss how TV series plan an occasional bottle episode, and not just because it affords dramatic concentration. It can save time and money in production.

Usually the bottle consists of more than a single room. The classic Kammerspielfilms roam a bit within a household and sometimes stray outdoors. But their manner of shooting provides a variety of angles that suggest continuing confinement. Dreyer went further in The Master of the House. He built a more or less functioning apartment as the set, then installed wild walls that let him flank the action from any side. Then editing could provide a sense of wraparound space.

The variations in camera setups throughout the film are extraordinary. Dreyer would create more radically fragmentary chamber spaces in La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc (1928), while his later films would use solemn, arcing camera movements to achieve a smoother immersive effect. (For more on Dreyer’s unique spatial experimentation, here’s a link to my Criterion contribution on Master of the House. I talk about the tricks Dreyer plays with chamber space in Vampyr in an “Observations” supplement on the Criterion Channel.)

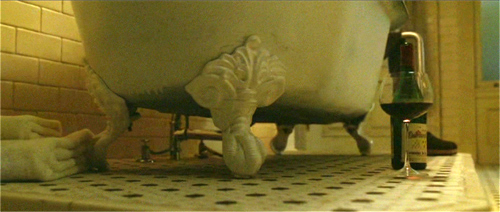

Likewise, Koepp’s screenplay for Panic Room allows David Fincher to move 360 degrees through several areas of a Manhattan brownstone. The film also offers a fine example of how our awareness of domestic details gets sharpened by a creeping camera.

Trust Fincher to find sinister possibilities in a dripping bathtub leg and a kitchen island.

Confined to quarters

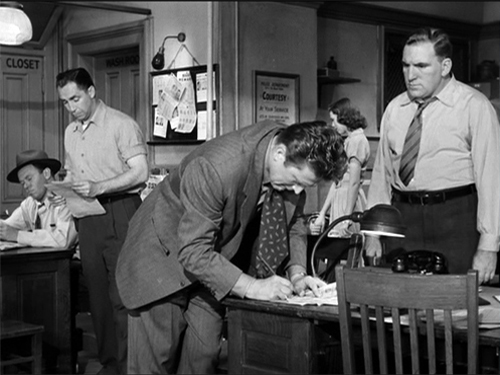

Detective Story (1951).

Many chamber movies are based on plays, as you’d expect. Unlike most adaptations, though, they don’t try to “ventilate” the play by expanding the field of action. Or rather, as André Bazin pointed out, the expansion is itself fairly rigorous. They don’t go as far afield as they might.

Bazin praised Cocteau’s 1948 version of his play Les parents terribles (aka “The Storm Within”) for opening up the stage version only a little, expanding beyond a single room to encompass other areas of the apartment. This retained the claustrophobia, and the sense of theatrical artifice, but it spread action out in a way that suited cinema’s urge to push beyond the frame. The freedom of staging and camera placement is thoroughly “cinematic” within the “theatrical” premise.

Depending on how you count, Hitchcock expanded things a bit in his adaptation of Dial M for Murder. Apart from cutting away to Tony at his club, Hitchcock moved beyond the parlor to the adjacent bedroom, the building’s entryway, and the terrace.

An earlier entry on this site talks about how 3D let Sir Alfred give an ominous accent to props: a particularly large pair of scissors, and a more minor item like the bedside clock.

Hitchcock gave us a parlor and a hallway in Rope (1948), but when Brandon flourishes the murder weapon, the framing audaciously reminds us that we aren’t allowed to go into the kitchen.

Bazin did not wholly admire William Wyler’s Detective Story (1951), despite its skill in editing and performances; he found it too obedient to a mediocre play. True, the film doesn’t creatively transform its source to the degree that Wyler’s earlier adaptation of The Little Foxes (1941) did; Bazin wrote a penetrating analysis of that film’s remarkable turning point. Detective Story is more obedient to the classic unities, confining nearly all of the action to the precinct station. Although I don’t think Wyler ever shows the missing fourth wall, he creates a dazzling array of spatial variants by layering and spreading out zones of the room. In his prime, the man could stage anything fluently.

As Bazin puts it: “One has to admire the unequaled mastery of the mise-en-scène, the extraordinary exactness of its details, the dexterity with which Wyler interweaves the secondary story lines into the main action, sustaining and stressing each without ever losing the thread.”

Some films are even more constrained. 12 Angry Men (1957), adapted from a teleplay, is a famous example. Once the jury leaves the courtroom, the bulk of the film drills down on their deliberation. Again, the director wrings stylistic variations out of the situation; Lumet claims he systematically ran across a spectrum of lens lengths as the drama developed.

But you don’t need a theatrical alibi to draw tight boundaries around the action. Rear Window (1954), adapted from a fairly daring Cornell Woolrich short story, is as rigorous an instance of chamber cinema as Rope. Here Hitchcock firmly anchors us in an apartment, but he uses optical POV to “open out” the private space.

With all its apertures the courtyard view becomes a sinister/comic/melancholy Advent calendar.

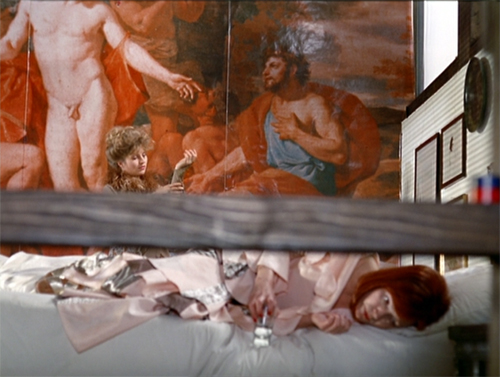

Fassbinder’s Bitter Tears of Petra von Kant (1972) denies us this wide vantage point on the outside world. This space seems almost completely enclosed. But Fassbinder finds a remarkable number of ways to vary the set, the camera angles, and the costumes. We’re immersed in the flamboyant flotsam of several women’s lives. The result is a cascade of goofily decadent pictorial splendors.

It’s virtually a convention of these films to include a few shots not tied to the interiors. At the end, we often get a sense of release when finally the characters move outside. That happens in 12 Angry Men, in Panic Room, in Polanski’s Carnage (2011) , and many of my other examples. Without offering too many spoilers, let’s say Room (2015) makes architectural use of this option.

On the road and on the line

Filmmakers have willingly extended the bottle concept to cars. The most famous example is probably Kiarostami’s Ten (2002), which secures each scene in a vehicle and mixes and matches the passengers across episodes. The strictness of Kiarostami’s camera setups exploit the square video frame and always yield angular shot/reverse shots. They reveal how crisp depth relations can be activated through the passing landscape or in story elements that show up in through the window.

Perhaps Kiarstami’s example inspired Danish-Swedish filmmaker Simon Staho. His Day and Night (2004) traces a man visiting key people on the last day of his life, and we are stuck obstinately in the car throughout. This provides some nifty restriction, most radically when we have to peer at action taking place outside.

Staho’s Bang Bang Orangutang (2005), a portrait of a seething racist, takes up the same premise but isn’t quite so rigorous. We do get out a bit, but the camera stays pretty close to the car. I discuss Staho’s films a little in a very old entry.

Like autos, telephones provide a nice motivation for the bottle, as Lucille Fletcher discovered when she wrote the perennial radio hit, “Sorry, Wrong Number.” The plot consists of a series of calls placed by the bedridden woman, who overhears a murder plot. The film wasn’t quite so stringently limited, but the effect is of the protagonist at the center of several crisscrossed intrigues.

A purer case is the Rossellini film Una voce umana (1948), in which a desperate woman frantically talks with her lover. It relies on intense close-ups of its one player, Anna Magnani.

It’s an adaptation of a Cocteau play, which Poulenc turned into a one-act opera. In all, the duration of the story action is the same as the running time.

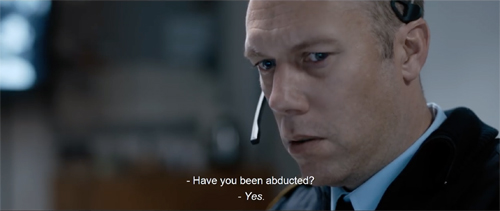

I wish Larry Cohen’s Phone Booth displayed a similarly obsessive concentration, but we do have the Danish thriller The Guilty, where a police dispatcher gets involved in more than one ongoing crime. We enjoyed seeing it at the 2018 Wisconsin Film Festival.

And of course car and phone can be combined, as they are in Locke (2013)–another play adaptation. Tom Hardy plays a spookily calm businessman driving to a deal while taking calls from his family and his distraught mistress. Those characters remain voices on the line while he tries to contend with the pressures of his mistakes.

House arrest, arresting houses

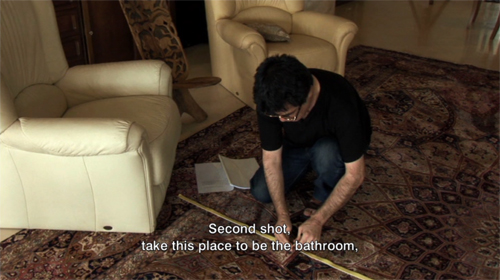

Sometimes you must embrace the chamber aesthetic. In 2010 the fine Iranian director Jafar Panahi was forbidden to make films and subjected to house arrest. Yet he continued to produce–well, what? This Is Not a Film (2012) was shot partially on a cellphone within (mostly) his apartment.

Wittily, he tapes out a chamber space within his apartment. Then he reads a script to indicate how absent actors could play it and how an imaginary camera could shoot it.

But his imaginary film still isn’t an actual film, so he hasn’t violated the ban. So perhaps what we have is rather a memoir, or a diary, or a home video? Panahi’s virtual film (that isn’t a film) exists within another film that isn’t a film. Yet it played festivals and circulates on disc and streaming. The absurdity, at once touching and pointed, suggests that through playful imagination, the artist can challenge censorship.

Panahi slyly pushed against the boundaries again with Closed Curtain (2013, above). Shot in his beach house, it strays occasionally outside. Next came Taxi (2015), in which Panahi took up the auto-enclosed chamber movie, with largely comic results.

More recently, he has somehow managed to make a more orthodox film, 3 Faces (2018), which considers the situation of people in a remote village.

The chamber-based premise needn’t furnish a whole movie. As in Room, Kurosawa’s High and Low (1963) is tightly concentrated in its first half. We are in two enclosures, a house and a train. The film then bursts out into a rushed, wide-ranging investigation. Large-scale or less, the chamber strategy remains a potent cinematic force.

They say that the last creatures to discover water will be fish. We move through our world taking our niche for granted. Cinema, like the other arts, can refocus our attention on weight and pattern, texture and stubborn objecthood. We can find rich rewards in glimpses, partial views, and little details. Chamber art has an intimacy that’s at once cozy and discomfiting. Seeing familiar things in intensely circumscribed ways can lift up our senses.

So take a break from the crisis and enjoy some art. But return to the world knowing that for Americans this catastrophe is the result of forty years of monstrous, gleeful Republican dismantling of our civil society. Rebuilding such a society will require the elimination of that party, and the career criminal at its head, as a political force. This pandemic must not become our Reichstag fire.

Yeah, I went there.

Thanks to the John Bennett, Pauline Lampert, Lei Lin, Thomas McPherson, Dillon Mitchell, Erica Moulton, Nathan Mulder, Kat Pan, Will Quade, Lance St. Laurent, Anthony Twaurog, David Vanden Bossche, and Zach Zahos. They’re students in my seminar, and they suggested many titles for this blog entry.

Bazin’s comments on Detective Story come in his 1952 Cannes reportage, published as items 1031-1033, and as a review (item 1180), in Écrits complets vol. I, ed. Hervé Joubert-Laurencin (Paris: Macula, 2018), pp. 918-922, 1059. My quotation comes come from the review, where he does grant that Wyler is the Hollywood filmmaker “who knows his craft best. . . . the master of the psychological film.”

The tableau style of the 1910s probably helped shift Dreyer toward the chamber model, which he learned to modify through editing. I discuss Dreyer’s relation to that style in “The Dreyer Generation” on the Danish Film Institute website. Also related is the web essay, “Nordisk and the Tableau Aesthetic.”

Some other examples could be mentioned, but I didn’t find them on streaming services in the US. It would be nifty if you could see the tricks with chamber space in Dangerous Corner (1934); fortunately it plays fairly often on TCM. There’s also Duvivier’s Marie-Octobre (1959), a tense drama about the reunion of old partisans.

I especially like the 1983 Iranian film, The Key, directed by Ebrahim Forouzesh and scripted by Kiarostami. It’s a charming, nearly wordless story of how a little boy tries to manage household crises when Mother is away. It has the gripping suspense that is characteristic of much Iranian cinema, and the boy emerges as resourceful and heroic (though kind of messy). Kids would like it, I think.

Also, I’ve neglected Asian instances. Maybe I’ll revisit this topic after a while.

P.S. 1 April 2020: Thanks to Casper Tybjerg, outstanding Dreyer scholar, for corrections about the nationality of The Guilty and the Staho films.

Gertrud (1964).

Vancouver 2019: Tales of oppression and resistance

Bacurau (2019).

Kristin here:

Examinations of social problems and portrayals of downtrodden people are fertile ground for makers of art cinema. This year’s festival saw many films from around the world tackling such subjects in original ways. Here are four impressive instances.

Castle of Dreams (2019)

Reza Mirkarimi is one of Iran’s top filmmakers, with three of his films having been put forward as Iran’s nominee for an Academy Award. In Castle of Dreams he has created a sort of nightmare version of the traditional child-quest tale so popular when Kiarostami and Makhmalbaf were at the heights of their careers. The protagonist, Jalal, has recently been in jail. The film opens as he is making some sort of a deal by telephone. His wife has just died after a protracted illness, and his sister-in-law, who had been taking care of Jalal’s two young children, is forced by her husband to turn them over to Jalal. But he clearly wants nothing to do with them.

Jalal sets out with them in his late wife’s car, picking up his Azeri fiancée on the way to Azerbaijan. He continuously snaps at the small children, Sara and Ali, and at his fiancée. It eventually comes out that he had taken his wife off life support and sold her heart for transplant, all without telling her brothers. Despite his occasional clumsy attempts to be kind to the children, any expectations that the audience may have that he will be charmed by them and transform into a responsible father are far too optimistic.

If this were a traditional child-quest plot, Sara and Ali might struggle to get back to their kindly aunt. Here, despite becoming increasingly miserable as Jalal’s full villainy is revealed, they are essentially prisoners in the back seat of the car (above). Ultimately the film takes a clear-eyed, realistic view of the future for this little family.

The acting carries much of the film. Hamed Behdad won a best-actor award at the Shanghai International Film Festival (where the film also won the best-picture prize). The child actors are charming and elicit considerable sympathy for their plight.

Song without a Name (2019)

Inspired by a real-life case that her journalist father investigated, Melina León’s first feature successfully generates sympathy for her two main characters and recalls the horrors of the past. Set in 1988, it follows Georgia, a pregnant indigenous woman living in a shack near the sea and scraping by as a street-seller of potatoes (above). Lured in by a radio ad, she visits a free clinic with a reassuring name, the “Saint Benedict.” The organization is anything but benevolent, however, spiriting her newborn daughter away for “check-ups.” Desperate to find the baby, she and her partner Leo encounter only indifferent police and other other government officials.

Eventually she finds a sympathetic helper in Pedro, a reporter who confidently promises that they will recover her baby, despite the fact that it has most likely been spirited out of the country for adoption. While Pedro pursues his investigation, Georgina finds her ability to purchase wholesale potatoes shrink in the face of rampant inflation, on top of which she discovers that Leo is apparently a member of the Shining Path terrorist group. Pedro meanwhile starts an affair with a gay actor in his apartment block, only to be threatened with exposure and death, presumably by the gang that runs the baby-stealing operation.

The film will inevitably be compared to Roma, even thought the films have nothing substantive in common. Both are black-and-white, Latin American films, and both heroines are pregnant; that’s the extent of the resemblance. León’s film has nothing of the nostalgia that permeates Roma, and Georgina is far more marginalized and downtrodden than Cuarón’s heroine.

León also is working with a far smaller budget and yet with the help of cinematographer Inti Briones she has fashioned a sophisticated and lovely film. One lengthy shot is particularly impressive. In it Pedro meets with a potential witness in a small motor boat. The camera, in another boat, catches it as a pulls away from the dock and glides around it as it turns,

The camera moves rightward with the boat but also moves in to show the woman sitting, apparently alone, in the boat.

A move further away establishes that Pedro is present, and we watch as the woman walks forward to sit beside him.

As she warns him of the danger of pursuing the kidnapping gang, the camera moves slowly in to emphasize her revelation that years before she had sold her baby to them

All the while the huge shantytown glides past in the background, emphasizes the extent of the poverty in the outskirts of Lima. The choreography of camera and action in this two-minutes-plus shot could hardly be bettered in a production with many times the budget. (A clip of this long take is currently posted on Youtube.)

The title seems to refer to the lullaby that Georgina sings, just calling her lost child “baby” because she never was given a name.

The film played in the Directors’ Fortnight at Cannes, where it received positive reviews in Variety and The Hollywood Reporter. It deserves further festival play, and we can hope that León can follow up with other films.

Sorry We Missed You (2019)

Then there is, Ken Loach, the veteran English filmmaker who continues to deal movingly with the plight of working-class people. In Sorry We Missed You–which deceptively sounds like a title for a comedy–tackles the gig economy and its grinding effect on one industrious couple and their children.

The inevitability of bad consequences seems obvious as the husband of the family, Ricky, agrees to become a driver for an express delivery service which transports packages for the likes of Amazon and other online sellers. He is not an employee but an independent agent, the supervisor emphasizes. Buying his own van supposedly will cost less than leasing, so he sells the family car for a down payment. His wife Debbie, a caregiver for home-bound elderly and handicapped people, is forced to take the bus to her widely scattered clients.

The couple’s long hours begin to tell on their teen-age son, who is turning into a school-skipping, graffiti-spraying delinquent, and their younger daughter, who is crushed by the stress of watching her family falling apart.

Loach is expert in depicting the challenges of such a job, from the pressure for drivers to load packages onto the van rapidly (bottom) to Ricky’s indecision over whether to risk a fine for illegal parking or deliver a package late (above). As he misses deadlines and skips work over family crises, the company’s sanctions and fines begin to accumulate. Ricky spirals into debt. Debbie, torn between duty to her family and the people who depend on her, faces similar problems in dealing with her helpless clients.

There is no happy ending here, though there is some suggestion that the dire situation of the family at least forces them to try and help each other out. Loach has created a plausible, gradual descent into near despair. He portrays the pressures of large companies and organizations that expect much of their “independent contractors” but offer little support in return.

Bacurau (2019)

At first glance, Bacurau represents a considerable departure from Kleber Mendoça Filho’s two previous films, both of which we saw at VIFF, Neighboring Sounds and Aquarius. Both dealt with unscrupulous methods used by real estate dealers to push people out of older neighborhoods to make way for gentrification. Now, co-directing with Juliano Dornelles (the production designer on the two previous films), Filho departs from the big city for a small village in the wilds of northern Brazil. The village, by the way, is imaginary, a fact that provides a running joke about the characters’ inability to find it on maps.

Someone in power wants the villagers to leave, again to make way for the exploitation of the land for undisclosed purposes. In a way, it’s not such a departure from the previous films as it seems. Blocked water sources and inadequate food deliveries have failed to budge the villagers, who make do on their own. The film opens with two villagers in a tanker truck full of water bound for Bacurau (above).

Having failed to uproot these determined peasants, the unseen power has brought in a group of wealthy hunters who are keen to gun down human beings and have been given carte blanche to exterminate the entire village. Delivery trucks appear with cargoes not of food but of dozens of empty coffins, a few of which are soon used for the first victims of the hunters (see top).

Despite the suspenseful and sometimes gory action, the film has considerable humor. It soon turns into a modern version of the politically charged Cinema Novo films of Brazil in the 1960s and 1970s. The peasants prove less helpless than they initially appear, and soon the hunted are hunting their hunters.

By this point members of the audience with whom we saw the film were cheering, and obviously there was a contingent of Brazilian speakers who got some jokes that we didn’t.

All in all, it’s a wild, entertaining film, though not for the faint of heart.

We thank Alan Franey, PoChu Auyeung, Jenny Lee Craig, Mikaela Joy Asfour, and their colleagues at VIFF for all their kind assistance. Thanks as well to Bob Davis, Shelly Kraicer, Maggie Lee, and Tom Charity for invigorating conversations about movies.

Sorry We Missed You (2019).

Vancouver 2019: Happy endings, art-film style

Tehran: City of Love (2018).

Kristin here:

The Vancouver International Film Festival has several strong threads running through it: world art cinema, documentaries, Canadian cinema, and films about art and artists. Sticking to any one or two of these would make for a rich viewing experience. I gravitate toward the “Panorama” program of mostly fiction films from around the world.

At one of these films, Tehran: City of Love, the Iranian director, Ali Jaberansari, and scriptwriter, Maryam Najafi, were present for a Q&A session. Clearly the audience has been charmed by their tale of three remotely connected characters all seeking love. One questioner asked what the pair’s next project was, which must always be cheering to the filmmakers. Another audience member simply thanked them for the film, saying that after seeing several grim movies, it was a pleasant experience to find one so funny and entertaining.

[Spoilers to come]

Certainly Tehran: City of Love is an entertaining film, but its ending is bittersweet at best. All three protagonists, after brushes with romance, end up alone. All may have learned something along the way, but they are all saddened by their failures. This year I have seen a couple of other films where the happy ending consists mainly of the central character letting go of bitterness and becoming reconciled to his fate. It seems as though grim storylines with unhappy endings are a staple of the festival film, and even comedies often avoid sending their audiences out on an entirely cheery note. Perhaps there is an assumption that an art film that is too entertaining risks not being taken seriously by festival programmers. Luckily, these three were included in the VIFF program.

Tehran: City of Love (2018)

Tehran: City of Love presents three central characters who are looking for love. Each has a problem to overcome. Mina is an overweight receptionist who, apparently resigned to her single status, targets attractive men who visit the cosmetic surgeon. She calls each, speaking seductively and arranging a date. She shows up for the date but does not identify herself, instead watching the man from a nearby restaurant table until he gives up in annoyance and leaves. At a class on the “geometry” of love, she meets a pudgy man who begins a courtship

Hessam is a body-builder with three championship titles in his past, now working as a trainer. He receives a part in a dubious film project and at the same time begins training an attractive young man who aspires to a championship. Hessam’s attraction to his trainee is subtly conveyed (above), and the young man seems friendly and seems possibly to reciprocate Hessam’s feelings.

Vahid, a talented mosque singer specializing in funerals, is dumped by his fiancée. A friend counsels him to become more lively and cheerful by singing at weddings. Vahid quickly makes the transition, which seems to improve his mood. He becomes friends with Niloufar, a female wedding photographer, who likes him but–as we know and Vahid doesn’t–she is awaiting a visa to allow her to emigrate to Australia.

Disappointments result. Mina’s beau is a married man in the lengthy process of divorcing his wife. The young man notices Hessam’s interest in him and switches to a new trainer. Niloufar reveals her imminent departure from Iran.

Tehran: City of Love is an impressive film for a second feature. The script by Jaberansari and Najafi weave the three stories together skillfully, keeping each story and the thematic connections among them perfectly clear. One might expect the three protagonists’ plotlines to come together. Hessam does at once point come to Mina’s office to get Botox treatments (presumably motivated by the film he is supposed to act in or to make himself more attractive to the young trainee), but nothing comes of that. Mina is close friends with Niloufar, but although the two talk about Vahid casually, Mina never meets him. The three characters are by chance in the same space by the final shot, but they remain unaware of each other. The title, unless we take it to be ironic, suggests that each may try again to find a partner, but the ending only hints that each has at least gained something from his or her brush with love.

It is also beautifully shot in widescreen, often employing what David has termed the planimetric shot, with the camera axis perpendicular to the background (see above and top). During the Q&A Jaberansari mentioned some of his film influences. (He was trained abroad in Vancouver and in London, where he now lives.) These included Roy Andersson, Elia Sulieman, Jim Jarmusch, Aki Kaurismäki, Jacques Tati, Fassbender, and Buster Keaton. Although Tehran: City of Love does not resemble any of these directors’ films closely–there are few long-take scenes or physical comedy played out in long shots–the list makes sense, mostly in the tone of the film.

Jaberansari and Najafi provided some helpful cultural context. They shot the film with official permission and also have permission to release the film in Iran, though no date for that has yet been determined. Despite the implied homosexuality of one character, only two minutes of cuts were required for the domestic distribution permit.

The emphasis on body-building, both in the gym and the scenes of men exercising in a mosque, reflects the fact that without bars, night-clubs, and other forbidden gathering-places, gyms and body-building are one milieu in which men can come together, including gay men.

At one point Vahid is arrested while singing at a “private” wedding. The phrase seems harmless enough, but private weddings often include men and women mixing in ways forbidden in the public weddings at which Vahid had previously performed.

Australia, they note, is the new destination of choice for Iranians seeking to move abroad, replacing Canada to some extent.

Sometimes Always Never (2018)

This film is largely a vehicle for Bill Nighy, contributing a mix of comically self-centeredness and pathos as Alan, a retired tailor. Years before his elder son Michael walked out of the house during a game of Scrabble and has never been heard from again. Alan has since been looking for him, neglecting his younger son, Peter, as well as his daughter-in-law and grandson.

Scrabble looms large in the plot. In one extended series of scenes, Alan and Peter show up in a small town to view the body of a young man who might be the missing son. During an evening in a bed-and-breakfast, Alan hustles the husband of a couple staying there, pretending to be an ordinary Scrabble player and winning £200 off the henpecked husband (above). Only later is it revealed that they, too, are there to examine the same corpse. Alan goes first emerges tactlessly and cheerily saying that the body is not Michael, despite the fact that the couple is about to perform the same grim task.

First-time feature director Carl Hunter adopts a playful style which at times resembles that of Wes Anderson. As with Tehran: City of Love, there are the planimetric shots(on a beach in Crosby otherwise populated by Anthony Gomley’s life-size statues, at bottom, and above, in the bed-and-breakfast Scrabble game). The characters drive in cars with blatantly obvious back-projected motion, and there are black-and-white inserts and brief animations. All these stylistic touches help lighten the tone of the underlying misery of the characters, though they also stand apart from the fairly straightforward presentation of most of the scenes.

The growing closeness between Alan and his shy grandson helps add a positive side to Alan and prepares the way for the inevitable outcome, as he learns to value the son he has over the one who clearly will never return.

A White, White Day (2019)

Most small producing countries have managed throughout the history of cinema to make films, and Iceland has been no exception. It was not until the 1990s that its films started attracting attention on the festival and awards circuit, but only now and then. Even today the local feature production hovers around only four a year. Still, we have learned to consider Icelandic films must-sees when they show up on festival programs.

Benedikt Erlingsson’s films have shown here in Vancouver, and we reported on Of Horses and Men in 2014 and Woman at War last year.

This year the contribution from Iceland is Hlynur Pálmason’s A White, White Day, his second feature. (His previous feature, Winter Brothers, played at our 2018 Wisconsin Film Festival, but we were in the process of buying a new house and missed it.)

“A white, white day” is a local phrase describing weather conditions that cause land and sky to become indistinguishable. It’s a perfect metaphor for confusion, for loss of bearings. We see it both literally and figuratively in the film. The protagonist, Igimundur, is a middle-aged policeman on leave for depression following a car accident that killed his wife. The film opens with the accident, although we don’t yet know who the driver is, occurring on a white, white day.

There follows a mesmerizing series of shots from the same vantagepoint, showing a lengthy series of shots of a pair of small buildings in a rural landscape, including these two.

All atmospheres and times of day area shown, from the light fog of the top shot to the heavier fog of the lower one, from bright sunny days to dark nights. Horses wander through in some, cars drive up in others, and gradually the ramshackle yard and structures become a home. We first glimpse Igimundur in the lower shot, though we don’t yet know who he is. The renovation of the buildings to make a home for his daughter and son-in-law, along with his beloved granddaughter Salka. Where Igimundur will go once they move in is never mentioned. Clearly the project is his way of coping with his grief, while he increasingly scorns the lack of help he receives from his psychologist.

Soon, however, he comes to believe that his wife had been having an affair, and he becomes increasingly abusive and violent, even toward his police colleagues and in front of Salka. The happy ending, which seems a trifle abrupt, sees him finally reconciling himself to the past and regaining his loving memories of his wife.

A White, White Day depends less on humor than the other two films, despite its occasional comic touches. Instead it is an absorbing family melodrama that most audiences would find entertaining.

For a useful brief history of Icelandic cinema, see here. So far it doesn’t include Palmason, but I expect he will soon be added.

We thank Alan Franey, PoChu Auyeung, Jenny Lee Craig, Mikaela Joy Asfour, and their colleagues at VIFF for all their kind assistance. Thanks as well to Bob Davis, Shelly Kraicer, Maggie Lee, and Tom Charity for invigorating conversations about movies.

Sometimes Always Never (2018).