Archive for the 'Narrative strategies' Category

Godard: The power of imperfection

Opening credits of Bande à part (1963).

DB here:

He was a sketchy fellow, to put it mildly. Childhood episodes of theft were followed by larceny as an adult, when he stole his grandfather’s Renoir and swiped cash from the Cahiers du cinéma till. Notorious for taking funding for projects that were never made, he once contracted for $500,000 to create a film on the Museum of Modern Art. He declined to visit the museum and instead shot the footage from stills at home. When The Old Place was finished, he agreed to introduce it in Manhattan. Hours before he was about to fly out (on the Concorde) he canceled, using anti-American cinephilia as his excuse: “I will return to New York when the films of Kiarostami are playing on Broadway.”

He liked to fight. Friends, romantic partners, performers, producers, government officials, and critics all felt his wrath. Jane Fonda was the target of Letter to Jane, a critique of a photograph of her meeting the North Vietnamese. The voice-over narration insisted it was not an attack on her as a person but as a “star.” Breaking with Truffaut led Godard not only to harangue his former pal (“liar”) and the films he made, but demand money so that he could make a film in response to Day for Night. Truffaut’s twenty-page reply called him “a piece of shit on a pedestal.” They never spoke again, and Godard’s remarks after Truffaut’s death praised him as a critic but omitted mention of his films.

Meeting Professor Pluggy

King Lear (1987).

I never had an abrasive encounter with Godard, but I always sensed that he was aloof at best. My first, very brief meeting was in spring of 1973 when he and Jean-Pierre Gorin visited the University of Iowa with Tout va bien (1972). Onstage, he was calm and earnest, while saying fairly provocative things. (Go here for a record of one session.) Asked what he thought of The Godfather, he replied: “The Godfather is shit. But there is a part of me that loves shit.” My eyewitness encounter took place in an elevator, when the host told Godard and Gorin that their schedule now had an empty hour. Godard said: “I am a prostitute. Why do you not use me?”

I had more prolonged exposure to him in 1981, when he visited a lecture series I was giving at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis. He was touring with Sauve qui peut (la vie) (1980), and the series director Melinda Ward took the opportunity for us to do a career review onstage. I planned to juxtapose clips from his work with those by other directors, and called him at Rolle to review my choices. He listened politely and said they would be fine, adding: “No matter what you choose, it always works.”

The session turned out well, with Godard modest about his efforts compared to those of Preminger (“like Manet”) and others. The only time the audience seemed ruffled was when he said of Jerry Lewis and the clip from The Ladies’ Man: “He is Robert Rauschenberg” (seems reasonable). For a couple of days Kristin and I drove him to interviews around town, and he spent his time reading Variety, noting only that he was pleased that Gance’s Napoleon was doing good business. Attempts to engage him in conversation were fruitless. But once onstage he was alert and genial, all soft speaking and gentle smiles.

The big stir came the following night with the screening of Sauve qui peut. A considerable portion of the audience objected to the film’s sexual politics. The most fraught moment, as I recall it, went like this:

Woman in the audience: Why do you make films only about women prostitutes, not male ones?

JLG (after a pause): They are different things.

Woman: How can you claim to talk about a women prostitute’s life?

JLG: Well, every time I hire a prostitute I ask her about her experiences.

Audience: stunned silence.

My last encounter was the most embarrassing. Invited to a conference on his work at Liège in 1986, I had horrible jet lag. In the first evening, a Q & A with the master, I made the mistake of sitting, as usual, in the front row. The problem was I kept dropping off to sleep. Every time I blinked awake, Godard was staring impassively at me. I thought no one noticed, but afterward one of the conference speakers said: “He was looking at you sleeping all the time.” Jesus.

I consider myself lucky to have escaped the treatment others have reported. Maybe it made it easier for me to admire his work. Yet even that admiration is tempered by exasperation. Bypassing von Stroheim and Buñuel, he might be the most annoying great filmmaker of all.

I’m not referring just to his obsession with female nudity, or his pretentious wordplay, or his pseudo-profundity. His provocation goes all the way down to the very texture of the film. In form and style he embraced irregularity. He will create a scene that’s conventionally beautiful, only to spoil it with a harsh disjunction or a silly gag or a deflating commentary. He seems to want to coax us to enjoy imperfection. His deformations of story and style are the result of testing the limits of what cinema had done, and might do.

Early work: Puncturing the plot

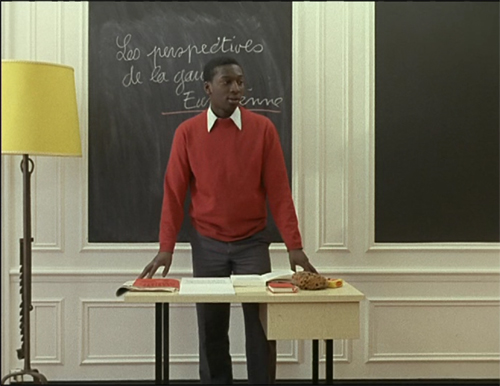

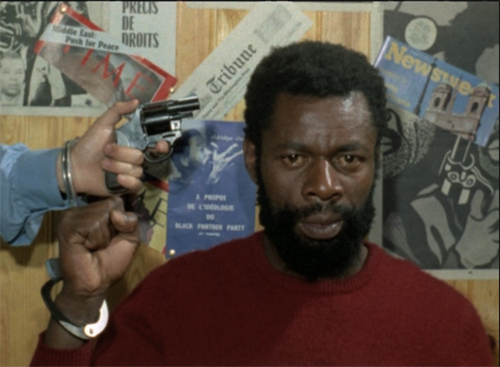

La Chinoise (1967).

Everything about him is troublesome. As a rough approximation, we tend to divide Godard’s career into three parts, but the results are peculiar. The early New Wave period runs from 1959 to 1967. The second, his overtly “agitprop” phase runs until 1980. Then we have “late Godard,” which dates from Sauve qui peut (la vie) until his death this year. What other artist has a “late” period running over forty years?

In all these periods, it’s common to say that Godard attacked, even destroyed, previous forms of cinema. But it helps to specify a bit more. I want to focus on his peculiar relation to narrative.

He often derided Hollywood’s reliance on stories, but throughout his career he depended on them. Asked about Hail Mary, he replied that the Bible had many good stories one could use. The project he proposed to Coppola about Bugsy Siegel and the founding of Las Vegas was initially titled simply “The Story.” Even the collage form he utilized in his last completed film, The Image Book, ends with a fictional tale about how Sheikh Ben Kadem, ruler of a kingdom called Dofa, tried to resist American imperialism.

One reason his early work succeeded, and survives as a body of classics, is that he relied on narrative conventions of traditional filmmaking. He rummaged through familiar genres: the couple on the run (Breathless, Pierrot le fou), spy intrigue (Le petit soldat), musical comedy (Une femme est une femme), social drama (Vivre sa vie, Two or Things I Know about Her), war picture (Les carabiniers), marital drama (Contempt, Une femme mariée), a robbery scheme (Band of Outsiders), a detective investigation (Alphaville, Made in U.S.A), and young romance (Masculin féminin).

More radically than his New Wave colleagues, Godard transforms these conventions. Sometimes he de-dramatizes intense situations, as in the violence of Le petit soldat and Les carabiniers. More commonly, he punctures the stories with digressions, skits, and uncertainties about character psychology. There’s also often a mockery of the very conventions invoked. Nonetheless the genres provide an armature for the audience to cling to, and the plots wrap up with more or less decisive endings.

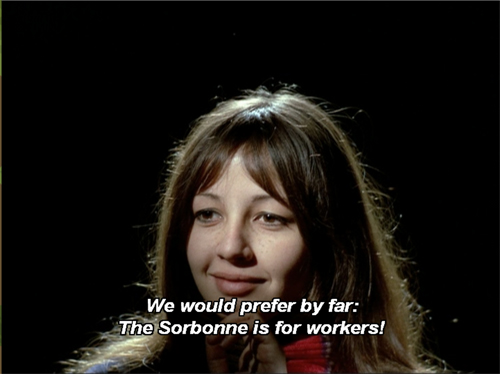

With La Chinoise, not only does the plot swerve from traditional genres (I suppose it’s a perverse roommate-relationships story) but the dynamic of the drama becomes overtly rhetorical, with both the characters and the overall narration setting out political theses. Weekend has a narrative core–a couple set out to visit and kill a rich relative–but the familiar journey schema becomes apocalyptic as the bourgeois encounter a world bent on revenge for oppression.

One strategy Godard pursues is to deform narrative by mixing in other formal principles. The later early films introduce passages cast in rhetorical form, as when characters indulge in extensive arguments about philosophy or politics (La Chinoise, Vivre sa vie).

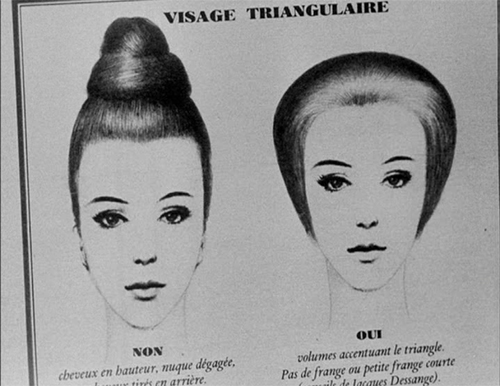

The early work also introduces passages of associational form. More and more often, Godard interrupts the action with cutaways to images that create commentary, analogies, and contrasts. Book titles are the simplest examples, but we also get the shots of fashion advertising interpolated into Une femme mariée and the landscape of consumer goods inserted into Two or Three Things.

With Le gai savoir of 1968, narrative is sidelined altogether as the primary characters conduct a political deciphering of a cascade of mass-media images.

The late 1960s-early 1970s quasi-Maoist films that Godard made with Jean-Pierre Gorin, sometimes under the rubric of the Dziga Vertov group, rely mostly on rhetorical and associational form, as in One Plus One and Pravda. Vladimir and Rosa, however, returns to narrative in providing a caricatural replay of the trial of the Chicago Eight, and Tout va bien is like the early work in embedding its political commentary in a more or less linear plot line.

After the break with Gorin, Godard continued to mix narrative and other formal options in Numéro deux, Ici et ailleurs, and several striking documentaries of the mid-1970s. Seen today, Comment ça va looks ahead to both the style and the construction of his late films in tracing two couples caught up in the politics of the mass media.

Style as rewriting

JLG par JLG (1995).

By emphasizing Godard’s reliance on narrative principles I don’t mean to reduce his originality. Like a Cubist painter creating a portrait or a still life, he needs some norms in order to introduce his disturbing deformations. He gives with one hand and takes away with the other, and to feel his work’s disruptive force we need a tacit background of what’s ordinarily done.

The same holds for matters of style. Most scenes in the early films rely on standard continuity, as I tried to show in one chapter of Narration in the Fiction Film. Even a film as fragmentary as Vladimir and Rosa depends on eyeline-match cutting.

Godard’s limited obedience to standard style makes the deviations stand out. In the shots above, the curtain background forestalls expectations of real space. Often the calculated disruptions of continuity have an arbitrary air, as if there’s no particular motivation except the opportunity to try something new. The celebrated jump cuts in Breathless, for example, seem to have no specific functions as motifs or narrative cues. They register as glitches, gratuitously spoiling a shot. Like DJ scratches and skips in hip hop, they come to form percussive passages that can be appreciated for themselves.

The early films try everything: labyrinthine camera movements, shots too short to be grasped, abrupt dropouts of sound and image, wisps of voice-over. Drama could be punctured or entirely suppressed. Alphaville expands a moment of suspense into a lyrical interlude, while Un petit soldat, after arousing our concern for the woman the hero meets, shoves her torture and death offscreen, reported in a tossed-off line of dialogue. All of cinema was simultaneously available to the New Wave directors, who at Langlois’ Cinémathèque saw a Griffith film alongside a Nicholas Ray picture. Godard gleefully ransacked film history, while deforming each device to see what he could make of it.

For example, Godard gave new life to a compositional option I’ve called planimetric framing. The camera shoots figures perpendicular to the background and places those figures frontally or in profile. Earlier it had been an almost ephemeral moment. Godard makes it a stylizing gesture, offering pictorial abstraction that short-circuits naturalistic drama (Pierrot le fou, Two or Three Things I Know about Her, Vladimir and Rosa).

What binds these all stylistic tactics together, I think is a broader narrational strategy. Godard carries the auteur theory to a new limit. In watching the film, we become aware not just of “a narrator” but of a specific agent, Godard the director, who insists that his story world is created and transformed by the practices of cinema. This isn’t just “Brechtian” distancing but persistent signs of this particular filmmaker’s creative work. Godard invites us to admire his sometimes annoying audacity.

The intertitles are the most evident signs of this agent’s activity, but so too are the unrealistic staging, the abstract compositions, the geometric camera movements, and especially the manipulations created in post-production. Sound mixing cuts off noises, muffles dialogue, provides anonymous voice-overs, scatters audio across many channels, and wedges in chunks of music. Post-production is seen as offering the filmmaker’s final, if sometimes inconclusive, revisions of his creation. It’s as if a novel were published as the copy-edited and marked up proofs of the author’s manuscript.

Critics are fond of saying that 1960s Godard changed the language of cinema. That’s sort of true, but we should remember things that were abrasive or alluring in his films have mostly been tamed by their assimilation to mainstream uses. Chapter breaks and intertitles are now recruited to create coherent story connections, as in Tarantino. The handheld camera is commonplace, but it serves chiefly as a wavering substitute for standard framing. His planimetric framings create a painterly abstraction, but in the hands of Wes Anderson they function as seriocomic establishing shots. Today’s directors use jump cuts mostly to compress time between stages of an action, not to annoyingly break the flow. And even our filmmakers who treat auteurism as a brand do not create the sense of the filmmaker’s hand fooling with every image and sound on the fly. Godard’s unpredictable tweaking asks us to adjust to a film that will undercut its own effects.

It makes me revert to a quotation I’ve used before. Supposedly Picasso told Gertrude Stein: “You do something new and then someone comes along and makes it pretty.” It’s worth noting that as mainstream films adopted his early technical tics, Godard abandoned most of them. His later work locks down the camera, favors depth staging over planimetric flatness, and avoids jump cuts. Three separate, disjunctive shots in Hélas pour moi show how he can reinvent continuity jumps, this time to harshly italicize a gesture: departure.

Late films: What the hell is going on?

Film Socialisme (2010).

The late films of Godard are tremendously varied, and I can’t claim to have seen, let alone assimilated, all the shorts and medium-length projects. But consider just two main types of features. There are the “film essays,” the prototype being Histoire(s) du cinéma (1988-1998). His last feature, The Image Book, is also an instance.

I’m disinclined to call them essays, since the ones I know don’t coherently marshal evidence to support a line of argument. They’re largely associational collages of found footage, suggesting pictorial or conceptual links among them. If you want a literary analogy, the poetry of Whitman or Pound would be close. The collage films also have rhetorical overtones, presenting ideas about, for instance, the way Hollywood evolved after World War II in Histoire(s). In its mixture of rhetorical and associational patterning, Le gai savoir was a rough prototype for the collage films; they simply delete the characters whose dialogue frames a flurry of images and substitute Godard’s own voice, or a merger of other voices.

I’m in that minority of Godardolators who find the collage films of limited interest. I find the philosophizing often facile, the claims about film history too broad, the politics obscure and even naive. Most essays take opposing views seriously enough to confront them, but Godard doesn’t rebut positions. He contents himself with post-production reworking of the imagery, twiddling the knobs to destabilize the image. As in the early films, his documentary images can’t escape transformation by the all-powerful filmmaker. At the least, comments might be scrawled on the images. But there will also be superimpositions, spasmodic slow motion, and freeze frames. Color values are garishly recast and aspect ratios pinched or stretched (Histoire(s), The Image Book).

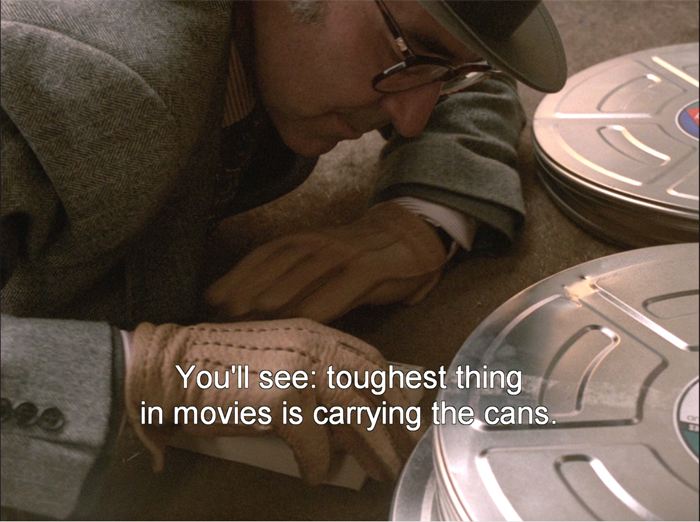

The demiurgic filmmaker can’t leave any picture alone. And of course his voice will guide the soundtrack. Other auteurs have a discreet signature; Professor Pluggy, thanks to all those RCA cables, gives us incessant audio graffiti.

For me the triumphs of the late career are the narrative features. Just as the early films deformed norms of classical storytelling, these can be taken as a continuing dialogue with contemporary “art cinema,” that psychologically-driven filmmaking that explores characters’ minds and relationships. While art-cinema narration sometimes challenges the viewer, Godard goes much further.

Again, story entices us. The late films return to situations he has long relied on, usually involving a romantic couple but sometimes also a family, as in the second section of Film Socialisme. There are recurring arcs of action: seduction and courtship, a dissolving couple, an investigation, or an artistic project–recording a song, making a film. There will be at least one long conversation, but also communication through body language, often violence.

The milieu is often that of a workplace–a factory or business, especially that of prostitution or filmmaking. (Passion makes the film studio a parallel setting to the factory.) Godard once said that the most important things in life are love and work, and these concerns supply his late works’ narratives with a recognizable world.

He sometimes provides “braided” plots, tracing two or or more groups of characters, parallel or intersecting. For Ever Mozart bears the label “36 Characters in Search of History.” Such braiding is comparatively rare in his early period. The plot will be partitioned by chapter divisions, but they don’t necessarily mark off portions of a story; just as often they interrupt a scene. Instead of braiding, we may get a sort of geometry, with two or three side-by-side stories–leaving us to sense connections among them. As the late career progresses, I think that those connections become more elusive.

Once we have narrative conventions in place, they can be blocked. Reviewers who confidently sum up a Godard plot don’t do justice to Godard’s astounding resourcefulness in impeding our understanding while still teasing us to try to get it. If the early films interrupt the action, in the later films we have trouble figuring out what the action is.

Bereft of point-of-view shots, visualized memories and dreams, appointments, and deadlines, these films avoid the commonplaces of modern movie storytelling. In that sense his films are “objective” in relying on characters’ behaviors to convey the action. But that behavior is often difficult to understand.

The characters may be unidentified, or inconsistent, or unrealistic in their actions and reactions. Why does the factory boss in Passion carry a rose in his teeth? Where does the twin of Alain Delon come from in Nouvelle Vague? On first seeing Hélas pour moi, I found every image ravishing and every scene baffling.

The most basic exposition about the characters’ relationships is often suppressed. Often you must watch the film several times to figure out kinship and alliances because there is only one hint, not the redundant signaling we get in mainstream cinema. And even when we’ve sorted out the characters’ roles, a scene may not have a clear-cut arc. We might enter the action partway through and leave it before the scene ends.

Part of the difficulty comes from an idiosyncratic style. He favors “troubled” master shots. The action is given a kind of coverage, but with obscure angles, partial framings, and time gaps between shots (alternatively, repetitions of dialogue). The editing of a scene often relies on the Kuleshov effect, with shots of single characters linked through eyelines.

Overall, a scene’s presentation is both sparse and dense. The action is built out of details, but sometimes things get overbusy, with jammed frames and layers of dialogue. And he loves to block our view of faces, by using the frame to decapitate major characters, or to interpose objects that make it hard to understand who’s present, or to tuck faces into apertures.

More blockage: main characters are often turned from us, plunged into shadow, or put out of focus, making expressions difficult to read. Combined with depth staging, these shots challenge us to carve out the prime narrative action (Passion, Éloge de l’amour, Notre musique).

Refusing the Steadicam (and today’s annoying slow track-ins to a character), Godard locks down the camera. He moves his figures through the shot and insists on filling the 1.37 ratio: every zone of space can matter. Any area of the image can harbor a significant gesture or facial expression (Hail Mary, Detective).

Godard’s fastidious attention to the precise image has not prevented him from his characteristic “overwriting” in post-production. The action, inevitably, is interrupted by intertitles. Classical music or ECM samples drop in and out, with a voice-over elaborating on what we see. Not content to let others supply English subtitles, Godard has lately provided his own, or simply suppressed them during certain stretches of dialogue or voice-over.

One result of this obscurity is to redirect our attention. If we can’t comprehend the full story action, we focus on other things, such as the composition of the image, the interplay of sounds, the expressiveness of the music. Alternatively, the absence of clear-cut scenic structure throws an emphasis onto the texts that his characters obsessively read, cite, and recite. And when we do see clearly, there are the faces, given weight by the shots devoted to them (Notre musique, Allemagne année 90 neuf zéro).

There’s also the historical dimension of the deformations. A Picasso still life asks us to compare it to the classic exemplars of the genre. Similarly, Godard asks us to compare his forms and styles to their precedents. Détective, one of the few late films that hark back to classic Hollywood, proffers a mystery (who killed the Prince two years ago?), investigated by three characters. There’s also suspense, and a deadline for payment during a prizefight. Alongside this noirish premise is a Grand Hotel template juggling several couples and romantic triangles. But this “ensemble film,” packed with opaque shots and fragmented scenes, is far from the trim construction of classical Hollywood.

Similarly, Éloge de l’amour, with its quest to grasp the Holocaust, invites us into an art-cinema investigation plot reminiscent of L’Avventura. But instead of a search for a missing person, we get a dense adventure split into two parts (black and white film, trembling color video) that does what it can to cloud the inquiry, while bringing out a critique of Hollywood’s treatment of history.

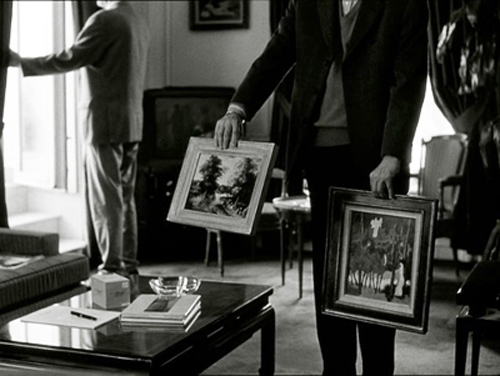

“The best criticism of a film is another film.” Taking film history as a conversation among filmmakers, Godard bounces off Rossellini’s Germany Year Zero, Pialat’s Sous le soleil du Satan, and Truffaut’s Man Who Loved Women and Day for Night (below, with Passion).

Late Godard has shadowed Tati with distracting long-shot staging reminiscent of Play Time (here, Hélas pour moi) and has paid homage to him in Soigne ta droite.

Even more pervasive is the invocation of Bresson. With a behavioral narrative, sound that replaces image, and the fragmentation of a scene through partial views, Godard seems to take a perverse “next step” beyond the master. Bresson died during the shooting of Éloge de l’amour, so there’s of course an homage, but more generally the late films’ style often radicalize Bresson’s technique, hands above all (Soigne ta droit, Détective).

Godard’s deformations not only “spoil” his own work but point to fresh possibilities in the traditions of narrative cinema.

Moments

Pierrot le fou (1965).

It’s not enough to note all the ways Godard impairs our comprehension of the story. As critics we need to show how the result can still add up to something coherent, even rigorous. We probably won’t be able to clarify everything, but we can try to show underlying patterns, in the way a critic can show a compositional logic underlying a cubist painting. I’ve tried to do this in two installments of our series on the Criterion Channel and in my analysis of Adieu au langage. Check the codicil to this entry for details.

But even if the overall strategy of disruption remains obscure, there’s a lot to engage us otherwise. Godard has given us scores of shots that no one had ever made before. Here are a few of my favorites, apart from ones I’ve already shown (Une femme mariée, Hail Mary, Made in USA, La Chinoise, Détective).

You have your own, I bet.

Given such shots, you can argue that the Godard narrative has been the bait to lure us into savoring privileged moments of cinema. Is this the heritage of Cahiers cinephilia–Godard’s version of “movie moments” that thrill us through what film (and video) can uniquely do? Or are they a refutation of the overblown CGI of Hollywood, showing what kinds of dazzling imagery can be achieved without special effects?

At any rate, such moments are especially resonant in the context of all the uncertainty. In all, we’re left with an aesthetic of exquisite spoilage. Godard teaches us to sense form underneath deformations, while still making imperfection a ripe artistic pleasure.

My references to Godard’s life are drawn from two excellent career accounts, Richard Brody’s Everything Is Cinema: The Working Life of Jean-Luc Godard (Metropolitan, 2008) and Antoine de Baecque, Godard: Biographie (Grasset, 2010). Brody’s exemplifies what a true “critical biography” should be.

On the Criterion Current, David Hudson compiles links to several Godard tributes. Don’t miss David’s own discerning essay here.

For some years I’d thought of writing a little e-book on Godard, complete with clips. (Why not rip him off as he has done with so many others?) But as I’ve aged I recognized that I’m overmatched. Instead, some entries on this site approach him in bite-size chunks. This piece goes into some detail about his preference for the 4:3 ratio, and how video versions in wider format degrade his compositions. Thoughts about his use of Scope in Le Mépris are elaborated in my Criterion Channel installment of Observations on Film Art. Another Criterion Channel commentary considers the use of the classic ratio in Vivre sa vie. Quick remarks about Le petit soldat are here, based on a visit to Belgium’s Summer Film College. (Visit Cinéa and photogénie to survey the vast number of events and critical studies the College has fostered over the years.)

At another session of the College I offered some ideas about the late films, particularly Nouvelle Vague. (And when will a video version give us the proper 1.37 image for this film? Same goes for Sauve qui peut (la vie) and King Lear.) This entry looks at Godard’s use of Bressonian editing in Hail Mary. Kristin offers a contextual analysis of Film Socialisme, with close consideration of the controversial subtitles. Earlier she took it as an example of the sort of film arthouses should be committed to screening. My comments on that film are here. At the Vancouver film festival KT and I saw 3 x 3D and offered some comments. One entry on Adieu au langage traces some of his 3D tactics, while another considers this film in relation to other late features and offers a detailed analysis of the film’s opening. These essays were revised into the Kino Lorber DVD liner notes.

Soigne ta droit (1987).

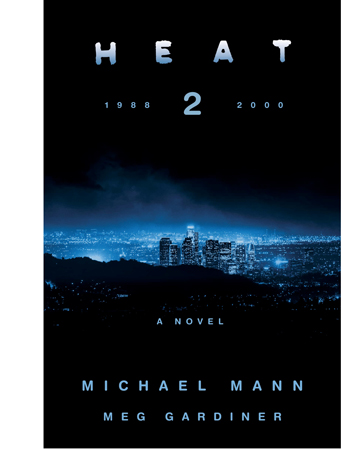

HEAT revisited

Heat (1995).

DB here:

Last year, Quentin Tarantino wrote a novel that extended and reconsidered the story of Once Upon a Time . . . in Hollywood (2019). Less elaborate is Michael Mann’s new bestseller Heat 2, written with Meg Gardiner. It’s not his first reworking of his film’s world: Heat (1995) was itself an expansion of a TV movie, LA Takedown (1989). Tarantino’s book was fairly experimental, as I tried to show, but Heat 2 is more conventional, being, as reviewers have mentioned, at once a sequel and a prequel to the original film. Yet it has its own interest, I think, and it provides me a chance to revisit a film I’ve long admired.

You’ve probably seen the film, but I’ll warn you of spoilers when I come to discuss the book.

Two genres for the price of one

In the film, Mann blends two schemas for crime plots: the heist film and the police procedural. What’s remarkable is the way both get expanded and interwoven to a degree rare in each of the genres.

The heist plot centers on Neil McCauley’s gang, consisting of Chris Shiherlis (Val Kilmer), Michael Ceritto (Tom Sizemore), and Trejo (Danny Trejo). The team members are married, and two have children. McCauley (Robert DeNiro) is a loner, living by the code that by being free of personal ties he can escape when the police close in.

In the course of the film, the gang plans three scores. The first, in the opening, is a robbery of an armored truck. Being short-handed, McCauley has had to add another team member, the sociopath Waingro, to consummate the heist. This robbery will reverberate through the film. Waingro shoots one of the truck drivers, forcing the gang to kill all of them. By seizing the bearer bonds of the money launderer Roger Van Zant and trying to sell them back to him, the gang sets off a cascade of broken deals and violent confrontations. McCauley fails to kill Waingro as punishment for damaging the heist, and Waingro emerges to help Van Zant stalk McCauley.

The second score, an effort to access precious metals, is aborted when McCauley realizes that the police are monitoring their preparations. The third score is a brutal bank robbery in which the team is virtually wiped out, with only McCauley and Chris surviving.

The heist plot adheres to many of the phases I’ve sketched in an earlier entry on the genre. The jobs are set up by the fence Nate and the computer whiz Kelso. The gang meets to plan each attack, with a division of labor among them. As often in the genre, the private lives of the robbers intervene. Chris, a gambling junkie, is in a fraught marriage with Charlene (Ashley Judd). Before the last score, McCauley advises Ceritto to walk away, since his wife Elaine takes good care of him. For the bank job McCauley recruits a prison pal Don Breedan (Dennis Hastert), whose wife Lilian (Kim Staunton) tries to sustain his effort to hold a job. And after Waingro kills Trejo’s wife Anna, the fatally wounded Trejo feels nothing left to live for. Most risky of all is McCauley’s growing love for Eady (Amy Brenneman), who makes him inclined to relinquish his solitude and unite with her after the bank job.

Braided with the heist plot is an investigation plot centering on homicide lieutenant Vincent Hanna (Al Pacino). He’s brought in through the armored-car murders and begins systematically to trace leads to the gang. In the usual procedural fashion, Hanna and his colleagues visit snitches, search records, tail and tape suspects, and gradually identify the gang. It’s their botched surveillance that induces McCauley to drop the second score. There emerges a game of tit-for-tat, as the gang in turn surveils the police and use their informants in the police to identify Hanna.

Police procedurals often fill out the action with scenes of the cops’ personal lives, and here that function is fulfilled by a portrait of Hanna’s failing marriage to Justine (Diane Venora) and his effort to nurture Lauren (Natalie Portman), their teenage daughter from another marriage. As the robberies test the family relations of the crooks, Hanna’s commitment to the investigation drives home to Justine his emotional distance and his refusal to open up to her about how he reacts to the crimes he encounters. Further intertwining the two plotlines, Hanna must also investigate the latest in a string of serial murders of prostitutes. We will learn that the killer is Waingro.

We might think of Hanna as the protagonist, with McCauley as the antagonist. But the weight given McCauley and his plotline inclines me to say that the film has two protagonists. Each is an antagonist to the other, with subsidiary antagonists (Waingro, Van Zant) adding pressure to the conflicts. Each man stands out, of course, by virtue of the presence of major stars. The performances are carefully calibrated. As McCauley, Robert DeNiro underplays to the point of paralysis: he acts mostly with the space between his hairline and his eyebrows.

By contrast, Al Pacio’s Hanna is full of swagger and bravado, using what Mann calls “manically extroverted” gestures and speech to intimidate others. But that’s on the job. At home, he’s taciturn, justifying his impassivity there as a way to preserve his angst and keep his edge for the street.

Mann’s screenplay teases us with brief confrontations between the two men. One takes place via surveillance video during the second score.

The most famous encounter is the celebrated diner scene, handled in protracted over-the-shoulder views. Here Hanna is much more subdued, modulating his eye movements to match McCauley’s constant scanning of the room.

The two plotlines culminate at the airport. McCauley interrupts his escape to kill Waingro and, reverting to his “discipline” of abandoning personal ties, must leave Eady alone. But he’s pursued by Hanna for a final shootout.

Apart from its binary-protagonist structure, the sweep of the film also makes it something of a network narrative. There are a great many characters and locales, and nearly every scene is elaborated in such physical detail that we have a wide-ranging survey of vivid personalities and situations. I haven’t mentioned the memorable informers whom Hanna interrogates, or Charlene’s louche lover Marciano, or Dr. Bob, the veterinarian who patches up the wounded Chris. Even the smallest roles (often played by recognizable actors) gain a memorable intensity. The breadth and depth of the story world suggests that the film might be a prototype for the “mosaic” structure of TV series like The Wire (20002-2008).

Work/ life imbalance

Narratives cohere largely through patterns of causality. One incident triggers another. But narratives also depend on parallelism–likenesses and difference among aspects of the story world. Parallels can draw comparisons among characters, locales, and situations. Michael Mann deliberately built Heat on parallels, as he points out in the 2005 DVD commentary track.

Most obvious is the comparison of Hanna and McCauley as men devoted to their work, at the expense of intimate relationships. (Parallels between cop and crook are virtually a convention of the policier.) Each man’s willed solitude is virtually a compulsion, and they recognize their affinity in the diner conversation. That is prepared for by almost telepathic reverse angles during the video surveillance, with the lighting’s angles presenting them as virtually split.

One benefit of the expansive plotting of the film is the way it creates parallels to other men. Nate, Kelso, and Van Zant seem as isolated as McCauley, though perhaps not out of principle. At the extreme is Waingro, also a loner, but one who preys on women–a psychopathic alternative to McCauley’s asceticism.

The film multiplies parallels among the couples. Ceritto has a warm relationship with his wife, and Trejo chooses death over life without Anna. Chris, for all his faults, is deeply in love with Charlene. Breedan responds resolutely to Lilian’s urging to reconcile himself to the unfairness of his new job.

Likewise, Hanna’s police colleagues are happily married. In parallel scenes, we see the gang and the squad enjoying lively restaurant dinners. Even Hanna unbends enough for a dance with Justine. Only McCauley, alone with the other couples, is marked as without a woman–a status that impels him to call Eady and invite himself over.

There are plenty of other parallels, not least that of vulnerable daughters, with the suicidal Lauren and the teenage hooker Waingro kills. But the ones I’ve just examined point up a common feature of classical Hollywoood plotting. Often American studio films interweave two lines of action, one based on work and another based on romantic love. Problems arise when the two can’t be reconciled. The husband may be consumed by pressures of the job, while the wife is neglected and her wishes dismissed.

More specifically, cop films and novels often play out the conflicting demands of duty (danger, disruption of routine) and love (of wife and children). This is exactly the life that McCauley foreswears and that Hanna tries to negotiate. The crux of the film is that both McCauley and Hanna entertain the possibility of a normal life only to find that their nature precludes it. Their counterparts seem to have managed it, but each gang member is also drawn to the adrenalin high of crime. “For me,” Ceritto says, “the action is the juice.” They all go along with the bank heist, with ruinous results. To a lesser degree, they are on the same spectrum as McCauley and Hanna.

The work/life tension is sometimes made apparent on the level of style. After Hanna dances playfully with Justine, Mann interrupts with the next scene, in which Hanna blocks the distraught mother from approaching her daughter’s corpse.

There is deeper concern, to the point of passion, in Hanna’s frantic embrace of this grieving stranger than in his flirtatious dance with his wife.

In such ways the film spares sympathy for the women. The plot brings out the parallel situations showing women beseeching the men to face their problems. Mann also uses visual motifs to heighten the comparisons. The women express themselves in shots of their hands. A bold composition in which Hanna blocks Justine heightens her gesture of annoyed resignation, and later close-ups show Charlene’s secret signal to Chris and Eady’s tension while waiting at the airport.

Men’s hands have other things to do, although one close-up of Neil fetching water for Eady suggests the man he might become.

The climax of this motif comes at the end, as Neil lies dying and Hanna accepts his handclasp.

Scrambled backstory

Now the spoilers for the novel commence.

In planning Heat 2 Mann and Gardiner faced some problems. At the end of the film several characters are dead, including the fascinatingly reticent Neil McCauley. To revive him, you have to create his backstory. Chris Shiherlis and his wife Charlene survive, but she has chosen not to give him to the police, so he will have to find a new way to live. And how will you treat Vincent Hanna–his past, his future?

The authors found several solutions, some of which vary Mann’s usual narrative strategies. The novel is broken into time periods, but not in the manner of the prototype for such sagas, Godfather II (1974). After a prologue sketching the action of the film, one section is devoted to the immediate aftermath of the bank robbery. This alternates Chris’s escape from LA and Hanna’s inability to track him.

The authors found several solutions, some of which vary Mann’s usual narrative strategies. The novel is broken into time periods, but not in the manner of the prototype for such sagas, Godfather II (1974). After a prologue sketching the action of the film, one section is devoted to the immediate aftermath of the bank robbery. This alternates Chris’s escape from LA and Hanna’s inability to track him.

There follows a flashback to 1988, set mostly in Chicago, in which McCauley and his crew launch new heists. These scenes alternate with episodes of Hanna, stationed in Chicago, investigating some brutal home invasions. Eventually the gang executing the invasions learns of McCauley’s plans for a southwestern raid on drug smugglers and decides to rip off the team. The initiative is led by the monstrous Otis Wardell, a Waingro on steroids, who enjoys raping the women whose homes he invades. Ultimately Hanna’s frustration with his boss’s constraints on his investigation leads him to quit the force.

Most Mann films are resolutely linear in plotting. Apart from the time-jumping montage at the start of Ali (2001), he prefers chronological narrative. But now Heat 2 jumps ahead to 1995-1996. Chris has fled to Paraguay, where he takes up with a Taiwanese family involved in the arms trade and cybercrime. He falls in love with the chief’s daughter Ana, whom he helps gain power in the family.

The action returns to the southern border in 1988, with a showdown between Wardell and McCauley. In the course of a protracted firefight, Wardell kills Elisa Vasquez, the woman McCauley loves. Losing her is what plunges McCauley into the willed solitude that he projects in the film.

After another passage from 1996 bringing Chris and Ana up to date, the action jumps to 2000, after the events of the film. Everyone is now back in Los Angeles, and Hanna, remembering Wardell from his Chicago days, vows to capture him, while Chis vows to kill Hanna in revenge for McCauley’s death. Complicating things is the presence of Gabriela, Elisa’s daughter, who becomes a new target for Wardell. All these forces converge at a bloody climax.

Why did Mann break the prequel material into blocks and alternate the time periods? I suspect it was to maintain interest in the runup to the film’s action. If all the 1988 action preceded Chris’ 1990s career in Paraguay, we would have lost both McCauley and Hanna about a third of the way through the book. Chris would have had to carry a large central chunk of the story. Even as a soldier of fortune, he just isn’t as charismatic as Hanna and McCauley, so holding the resolution of the McCauley plotline in suspension keeps us turning the pages. Elisa’s death and McCauley’s devastation provides a strong lead-in to the film we have. Thereafter, the 2000 followup serves to wrap up nearly all the action. (The last line presents is a dangling cause that could lead to yet another sequel.)

The novel is less concerned with parallels than the film, although Ana’s frustration with the closed-in Chris matches that of Heat‘s wives. And Hanna’s fury at Wardell’s rape and beating of a teenage girl fuels his mission to find the gang, while thanks to a coincidence Wardell realizes that the waitress in a diner is the daughter of the woman he murdered in the desert. What knits the novel together most tightly is the premise that Hanna, McCauley, and Wardell were all in Chicago in the same years, but they were largely unaware of each other. We see links that the characters aren’t aware of.

This roaming-spotlight viewpoint is at work in the film as well, with the constant crosscutting of cops and crooks. But Mann and Gardiner take omniscience farther by penetrating the minds of the characters. Scene by scene we learn what the major characters are thinking, with some scenes containing several shifts of perspective. It would be as if the film gave us voice-overs from Hanna, McCauley, Chris, and others. The novel’s inner monologues remind me of Mann’s commentary track for Heat, which frequently draws larger conclusions and fills us in on what the characters are thinking. When Drucker pressures Charlene to give up Chris, Mann’s commentary reminds us that he’s trying to “build emotional solidarity” with her “despite having “a very short window.” Of Heat‘s two protagonists, he says:

These are the only two guys like each other in the universe. . . they are fully aware and conscious of who they are.

In the novel’s prologue the passage is:

Each navigated the future racing at him with eyes wide open. . . Polar opposites in some ways, they were the same in taking in how the world worked, devoid of illusions and self-deception.

The result is a narration that is, by the standards of Hammett or Elmore Leonard, over the top. On the same page, we get: “The detonation behind her eyes is seismic” and “For a second, she looks like she might explode.” Likewise, the perspective-shifting encourages scenes to be overelaborated; nothing is left to the imagination. But as with a lot of pulp writing, the novel has a raw power. We can treat it as a package, wrapping a Mann plot and dialogue in blunt, brash commentary.

Novel as script

A great deal of the appeal of a Michael Mann film is its richly textured surface. He is a “realistic” director insofar as he carefully researches a film’s milieu and takes pride in exact historical details. During a visit to Madison, he praised Dunkirk for Nolan’s attention to the Bakelite knobs on the aircraft. Yet Mann is also a pictorialist, always seeking striking, expressive shots that can de-realize the most familiar landscape, often through long lenses.

His early interest in video capture indicates both his realist impulse and his gift for abstract color design. Wanting to reveal LA at night in Collateral (2004), he wound up with night visions like nothing else on earth. Add in his talent for innovative film music. Heat‘s eclectic, melancholic score, so different from that of the routine action picture, is a big part of its power. So approximating a Michael Mann film on the printed page is far from easy.

Heat 2.0 tries. Written in the present tense, it has the staccato quality of a screenplay.

Gunfire. Deep. A rifle. Behind, them, rounds hit the connecting door from the far side. Somebody kicks it. Chris spins and fires a three-shot burst. They hear a body fall. More shots come through the wood, splintering it.

Reading it, you may find yourself hearing the dialogue in the voice of DeNiro or Pacino.

Ceritto glances around. The walls of boxes gleam in the spooky light. “Which one has the Holy Grail?”

Neil opens a gym bag. “Don’t matter. You find Jesus Christ, haul him out and hand him a sledgehammer.”

Hanna leans down into Alex’s face and grabs the crucifix in his right ear and rips it out through the lobe. Alex screams. Blood pours from the tear.

“Asshole!” Hanna shouts. “What the fuck do you think we’re gonna do? You are gonna flip, you dumb prick. You are gonna tell me everything I want to know, you cocksucker!”

He jerks Alex’s chin up, stares into his eyes, and shoves forward the cross. “The power of Christ commands you! I am your motherfucking exorcist. Tell me!”

Mann says he hopes to make a film of the novel. If he does, readers will hope that passages like these make their way into it.

Heat has proven to be an enduring modern classic. It’s encouraging that a followup to a movie nearly thirty years old can stir such widespread interest. Whatever happens to Heat 2, it shows that at age 79 Mann has not lost his lustre.

Nick James’s appreciative monograph on Heat offers many insights into the film. I discuss the heist genre and the police procedural in my forthcoming book Perplexing Plots.

Heat (1995).

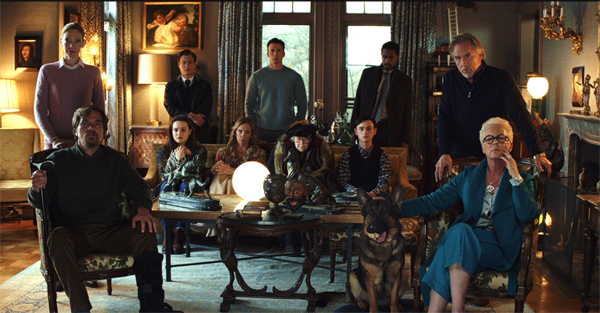

Enter Benoît Blanc: KNIVES OUT as murder mystery

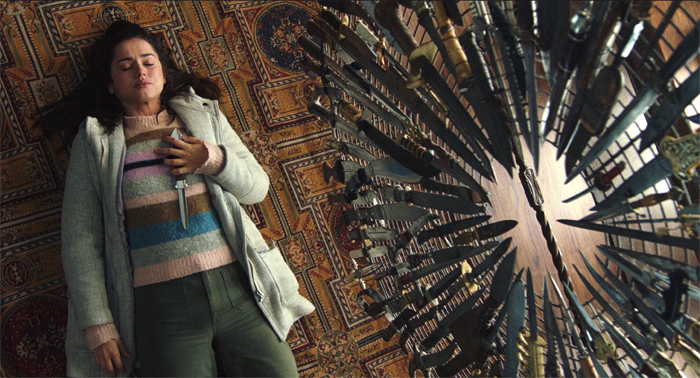

Knives Out (2019).

DB here:

Now that a sequel, Glass Onion, has been announced for the Toronto International Film Festival, it seems a good time to look back at Rian Johnson’s first whodunit Knives Out. The effort has a special appeal for me because it chimes well with arguments I make in Perplexing Plots: Popular Storytelling and the Poetics of Murder.

I don’t analyze Knives Out in the book, but it would have fitted in nicely. The movie exemplifies one of the major traditions I study, the classic Golden Age puzzle, and it shows how the conventions of that can be shrewdly adapted to film and to the tastes of modern viewers. In addition, Johnson’s film supports my point that the narrative strategies of “Complex Storytelling” have become widely available to viewers, especially when those strategies are adjusted to the demands of popular genres. Historically, such strategies became user-friendly, I maintain, partly because of the ingenuity demanded by mystery plotting.

Needless to say, spoilers loom ahead.

Revisiting and revising

The prototypical puzzle mysteries are associated with Anglo-American novels of the 1920s-1940s, the “Golden Age” ruled by talents such as Dorothy L. Sayers, Anthony Berkeley Cox, John Dickson Carr, Ngaio Marsh, Ellery Queen, and many others–supremely by Dame Agatha Christie. Similar books are still written today, often under the guise of “cozies” because they supposedly offer the comforting warmth of familiarity. Golden Age plotting flourishes in television too, in all those (largely British) shows about murder in supposedly humdrum villages.

Knives Out relies on Golden Age conventions from top to bottom. A rich, odious family is overseen by a domineering patriarch, mystery novelist Harlan Thrombey. When he’s found dead in his mansion, apparently of suicide, his family members become nervous because each has a guilty secret. The conflicts are brought into focus when it’s revealed that Harlan changed his will so as to disinherit all his offspring. He leaves his fortune and his house to Marta Cabrera, the nurse who administered his medications and became his friend and confidant. Is there foul play? Investigating the case are are two policemen and the private investigator Benoît Blanc. They must decide whether Harlan’s apparent suicide is actually murder and if so, who’s the culprit.

Johnson organizes his plot around many classic techniques. In the Golden Age, writers tended to fill the action out to book length by adding more crimes, such as blackmail schemes or a series of murders. Both of these devices are exploited in Knives Out. Marta is apparently the target of an extortioner, and the family housekeeper Fran is the victim of a poisoner. The film also employs the least-likely-suspect convention (a favorite of Christie’s) and a false solution (another way to fill out a book). Johnson supplies traditional set-pieces as well: the discovery of the body, a string of interrogations of the suspects, the assembling of suspects to hear the will read, and a denouement in which the master sleuth announces the solution by recapitulating how the crime was committed.

The conventions are updated in ways both familiar and fresh. The sprightly music and the flamboyant bric-à-brac of Harlan’s mansion deliberately recall Sleuth (1972), another reflexive, slightly campy revisiting of murder conventions. Johnson wanted to evoke the all-star, well-upholstered adaptations of Christie novels like Murder on the Orient Express (1974, 2017) and Death on the Nile (1978, 2022). But he has courted younger audiences with citations (the title is borrowed from Radiohead) and social commentary, such as references to Trump, neo-Nazis, and illegal immigration. The Thrombey clan’s inability to remember what country Marta came from reminds us of something not usually acknowledged about Golden Age classics: they often provided satire and social critique of inequities in contemporary society. (In the book I discuss Sayers’ Murder Must Advertise as an example.)

Like earlier Christie adaptations, Johnson’s film has recourse to flashbacks illustrating how the crime was actually committed. In Benoît Blanc’s reconstruction of the murder scheme, rapidly cut shots illustrate how the family black sheep Ransom sought to kill Harlan by switching the contents of his medicine vials, which would make Marta the old man’s murderer. But her expertise as a nurse unconsciously led her to switch the vials again, so she didn’t administer a fatal dose. This forced Ransom to continually revise his scheme, chiefly by destroying evidence of Marta’s innocence and trying to murder Fran, who suspected what he had done.

All of this is carried by the now-familiar tactic of crosscutting Blanc’s solution with shots of Ransom’s efforts, guided by Blanc’s voice-over. At some moments, the alternation of past and present is very percussive, with echoing dialogue (“You’re not gonna give up that,” “You’ve come this far”). For modern audiences, this swift audio-visual revelation of the “hidden story” is far more dynamic than a purely verbal recitation like that on the printed page.

Johnson tries for a more virtuoso revision of a classic convention in treating the standard interrogation of the suspects. Lieutenant Elliott’s questioning, followed by questions posed by Blanc, consumes an astonishing sixteen minutes of screen time. Such a lump of exposition could have been dull. But the accounts provided by Harlan’s daughter Linda, her husband Richard, Harlan’s son Walt, his daughter-in-law Joni, and Joni’s daughter Meg are brought to life by flashbacks to the day of Harlan’s death. Aided by voice-over, we get a sharp sense of each character’s personality while the mechanics of who-was-where-when during the birthday party are spelled out. Some flashbacks are replayed in order to alert us to disparities in the stories, which stir curiosity and set up further lines of inquiry. The technique isn’t utterly new, though; in the book I show that such shifts across viewpoints emerged in mystery films from the 1910s onward.

The pace picks up when, instead of sticking to one-by-one witness accounts, Johnson starts to intercut them, showing varied responses to the same questions.

The editing creates a conversation among the witnesses, as one disputes the testimony of another. This freedom of narration, mixing different accounts in a fluid montage, plays to modern viewers’ abilities to follow fast, time-shifting narratives.

The use of voice-over to steer us through the flashbacks takes on new force when Elliott and Blanc question Marta. Her account of the fatal night is given not as testimony but as her memory. She recalls tending to Harlan after the party, starting a game of Go with him, and then discovering that apparently she gave him a lethal dose of morphine. She’s distraught, but he consoles her and instructs her in how to cover up her mistake. His scheme, which involves an elaborate disguise and a secret return to his bedroom, is designed to give Marta an alibi by showing her apparently leaving before he dies.

In her memory Harlan’s voice-over narrates her flashback as she executes his plan. But she doesn’t confess to Elliott and Blanc. Following Harlan’s instructions, Marta lies to exonerate herself. Her propensity to vomit when she tells a lie drives her to the commode, but the police don’t notice. She has apparently fooled Blanc, who considers that her account “sounds about right.”

In such ways Johnson retools scenes of the police interrogation for contemporary viewers. But he goes further in revising Golden Age tradition. Well aware of the tendency of the puzzle plot to indulge in plodding clue-tracing, he provides a deeper emotional appeal.

Immigrants get the job done

The Golden Age plot relies on an investigation, the scrutiny of the circumstances leading up to and following a mysterious crime, usually murder. Plotting came to be considered a purely logical game, a matter of appraising motives, checking timetables, pondering clues, testing alibis, and eventually arriving at the only possible solution. These conventions were canonized in books like Carolyn Wells’ Technique of the Mystery Story (1913) and in many writings by authors. But some writers recognized that the emphasis on a puzzle tended to eliminate emotion and promote a boring linearity in which the detective poked around a crime scene and questioned suspects one by one.

Authors sought ways to humanize the investigation plot. Sayers filled it out with romance, social commentary, and regional color. Hardboiled novelists like Hammett and Chandler, who relied on many Golden Age conventions, turned the investigation into an urban adventure, with the threat of danger looming over the private detective. Others tried to blend in elements of the psychological suspense novel, as Nicholas Blake does in The Beast Must Die (1938), which traces how a bereaved father searches for the hit-and-run driver who killed his son.

Rian Johnson tries something similar in Knives Out. Into the investigation of Blanc and the police, he inserts a woman-in-peril plot. Although we’re introduced to Marta early in the film, she’s pushed aside for about half an hour as the inquiry takes over in the interrogation sequences I’ve mentioned. Then Blanc takes a kindly interest in her and probes her knowledge of Harlan’s attitude toward his family. And then, after Lieutenant Elliott becomes convinced that it’s a suicide, Marta is questioned. At this point, she comes to the center of the film and becomes its sympathetic protagonist and central viewpoint character.

Her memory episodes reveal that she believes she accidentally killed Harlan. But out of self-preservation and obedience to his orders, she doesn’t confess. She tries to ease away from Blanc, but he asks her to be his “Watson.” The rest of the plot forces her to accompany the investigation. Panicked that her scheme will be revealed, she often tries to suppress evidence: futzing up surveillance footage, traipsing over the muddy footprints she left, trying to throw away a piece of siding that she dislodged that night. Marta’s situation recalls that in The Woman in the Window (1944) and The Accused (1949), and in the TV series Columbo, in which guilty protagonists must watch as their trail is exposed.

Marta’s only ally appears to be Ransom, Harlan’s ne’er-do-well grandson. He justifies his concern as partly selfish: If she gets away with it, she can share Harlan’s legacy with him. As in many domestic thrillers, this handsome helper is also a little sinister, but Marta accepts his advice for how to respond to an anonymous threat of blackmail. When Marta discovers that someone has nearly killed the housekeeper Fran, she vows to confess. By then, however, Blanc has solved the mystery and absolved her of guilt.

Johnson deliberately made Marta a center of sympathy as a way of humanizing the investigation.

Very early on in the game I wanted to relieve the audience of the burden of “Can we figure this out?”. . . . I don’t think that’s a very strong narrative engine to drive things. I think that’s very intellectual and that clue-gathering–after a while you recognize “No, I’m not gonna figure this out,” so you kind of sit back on your hands and wait for the detective to figure it out. . . .

So the notion of tipping the hand early and giving this false but very convincing picture from Marta’s perspective of “I’ve done this and I’m in a lot of trouble.” . . . Could we do that so you’re genuinely on the side of the killer?. . . Once you’ve done that it’s very interesting because of the mechanics of the murder mystery, the fact that you know the detective always catches the killer. . . . The looming threat is that we know how mysteries work and we know that the detective catches [the killer] at the end. And we’re worried for Marta. We’re worried, “How is she possibly going to get out of this situation?”

Johnson uses several other tactics to put us on Marta’s side. While the performances of the actors playing the Thrombeys leans toward grotesquerie, Ana de Armas plays Marta more naturalistically. In time-honored Hollywood fashion, Johnson also makes Marta ill-treated. She’s dominated by the family who pretends to love her, and as an immigrant she’s in danger of seeing her mother deported. When she is named Harlan’s heir, the family descends on her like predators. In the end, as in many psychological thrillers, the woman in peril turns into a resourceful combatant. She bluffs Ransom into confessing his scheme, and only when she vomits on him does he realize she’s fooled him with a lie. We can enjoy the innocent trapping the guilty.

The game’s afoot. Which one?

The Golden Age story is more than a puzzle. It’s posited as a game. Of course the murderer is at odds with the detective, with each trying to outwit the other. At another level, the game is a battle of wits between author and reader. John Dickson Carr sums it up.

It is a hoodwinking contest, a duel between author and reader. “I dare you,” says the reader, “to produce a solution which I can’t anticipate.” “Right!” says the author, chuckling over the consciousness of some new and legitimate dirty trick concealed up his sleeve. And then they are at it—pull-devil, pull-murderer—with the reader alert for every dropped clue, every betraying speech, every contradiction that may mean guilt.

Golden Age authors realized that the core mystery could be enhanced by techniques that both mislead the reader and drop hints about what’s really going on. The cultivated reader became alert not just for characters who might lie but for narration that was engineered to be misunderstood. Golden Age authors weaponized, we might say, every literary device to steer the reader away from the solution. The trick was to do this without cheating.

If this genre is a game, then, following sturdy British tradition, “fair play” becomes the watchword. Earlier detective writers, notably Conan Doyle, did not feel obliged to share all relevant information with the reader. The master sleuth was likely to discover a clue or a piece of background knowledge that he or she kept quiet, the better to flourish it in triumph at the denouement. Instead, Golden Age authors made a show of telling everything.

The concept of fair play was made explicit in Ellery Queen’s novels, which included a climactic “challenge to the reader” explaining that at this point all the information necessary to the solution was now available. (This device was replicated in the EQ TV series.) Even without this pause in the narration, Golden Age writers were careful to supply everything before the big reveal.

Knives Out is very much in the game tradition. It knowingly follows self-conscious “meta”-mystery films like Sleuth, The Last of Sheila (1973), and Deathtrap (1982), all of which flamboyantly exploit classic conventions (often with crime writers at the center of the plot). Accordingly, Johnson is aware of the need to play fair.

A straightforward example occurs in the interrogation sequence. Members of the Thrombey family tell Blanc and the police that Harlan’s last day with the family was a happy occasion. But the flashbacks reveal to us that they’re lying. We see Harlan fire Walt as his publisher, confront Richard with his infidelity, and cut off Joni’s funding for Meg’s tuition. Soon enough Blanc will intuit their deceptions and ask Marta for confirmation, but the flashbacks make sure we grasp their possible motives for killing Harlan.

But telling everything required telling some of it in deceptive ways. Otherwise, there’d be no puzzle. The craft of Golden Age fiction demanded skillfully planting crucial information that can be (a) recalled at propitious moments by the detective but (b) neglected by the reader (“I should have noticed that!”). Perplexing Plots traces various stratagems for achieving how authors muffled crucial information through ellipsis, distraction, and other tactics.

Consider Fran’s dying message. As Marta bends over her, Fran gasps, “You did this.” Since we’ve been led to believe that Fran is blackmailing Marta, it seems to confirm that she’s got proof of Marta’s guilt in the toxicology report. But the dying message turns out to be equivocal. Fran is actually saying, “Hugh did this”–identifying her would-be killer. Huh?

Early in the film when Ransom comes to the mansion, the police greet him as “Hugh Drysdale,” to which he replies, “Call me Ransom. Ransom is my middle name. Only the help calls me Hugh.” Fair play, but given to us in a distracting way. The line is played down: Ransom delivers it quickly as he’s turned from the camera and strides into the house, and the policemen’s reactions are more prominent in the shot.

To play fair, Johnson reiterates the name just before the revelation, when Blanc addresses him as “Mr. Hugh Ransom Drysdale.” Since in Fran’s scene we can’t tell the difference between “You” and “Hugh,” file this under Carr’s category of “legitimate dirty trick.”

As a result, anything can become a clue for interpretation/misinterpretation. But for Golden Age creators, authorial craft isn’t only a matter of producing clues. Clues are available to the investigators and are crucial to the solution. But at the same time the author can supply hints in the narration, addressed to us behind the backs of the characters. An instance in Knives Out is the title of one of Harlan’s books, glimpsed in a montage of his bookshelves. In a film reliant on syringes, The Needle Game would seem to be a tip-off.

Or a hint can become a clue eventually. After Marta’s wild night covering up her “crime,” she rushes home and takes refuge in front of the TV. As she nervously taps her foot, a close-up reveals a single bloodstain on her sneaker.

She’s unaware of it, but the stain opens the possibility that it could incriminate her later. The film lets us forget it until the very end, when Blanc says he knew she was involved in Harlan’s death from the start, when he spotted the bloodstain. The hint for us became a clue for him.

Golden Age plotting invites attention to minutiae of presentation. Although Agatha Christie is sometimes condemned as a clumsy writer, Perplexing Plots tries to show that she often mobilizes a flat style to mislead us. Similarly, the attentive viewer will notice little felicities in Knives Out. For instance, when we first see Marta return to the mansion through the forest path, a shot shows her leaving the tracks she’ll later try to smear over. But in Blanc’s reconstruction, we see Ransom returning to the mansion by balancing on the wall lining the path, so as to leave no traces in the mud.

Had Ransom walked on the path, Johnson would have been besieged by Twitter complaints.

All this is a matter of self-conscious artifice. As Johnson notes, few readers take seriously the task of solving the mystery themselves. One member of the Ellery Queen collaboration admitted: “We are fair to the reader only if he is a genius.” The fair-play convention is at once a pretext for the display of authorial ingenuity and a source of artistic power–proof that a plot can harbor a hidden intricacy unsuspected by the reader. One dimension of connoisseurship in the classic mystery is the reader’s admiration of artifice, a taste for elaborate construction. If it’s all in the game, then we’re no longer committed to mundane realism. A portrait can whimsically change from scene to scene.

Henry James argued for a through-composed form of the novel, where every detail was carefully judged for its effect and its balance with others. An unexpected legacy of Jamesian formalism, I think, was the Golden Age authors’ ambition to make each story a tour de force, a test of readers’ skills and a revelation of unexpected resources in storytelling technique. Mystery stories are ingenious, as Ben Hecht noted, because they have to be.

The film’s rapid pace, time-shifting, and looping replays exemplify current tastes for what’s been called Complex Storytelling. But one task of my book is to suggest that popular storytelling has been complex for quite a while. The techniques have become refined and revised, and their appeal has been sharpened by emerging audiences (e.g., in the 1990s) and new technologies (e.g., video that allows replays).

We were sensitized to these techniques by mystery fiction throughout the century. The play with incompatible viewpoints, reruns of action bearing new significance, the strategic use of ellipsis–all are there in the Golden Age tradition. Likewise, the notion of fair play persists in all those “twist” films that flash back to show us actions that take on a new significance. Golden Age strategies, and mystery plotting more generally, have prepared audiences to expect pleasurable but “fair” deception in all genres. Knives Out, among other accomplishments, helps us understand how today’s sidewinding stories have roots in a genre that’s too often dismissed as mere diversion.

The quotations from Rian Johnson come from the Blu-ray supplement to Knives Out, “Planning the Perfect Murder,” between 2:21 and 4:20. The supplementary material on the disc is exceptionally detailed and reveals Johnson’s keen knowledge of the history of mystery fiction and film.

Exceptional studies of Golden Age mysteries are LeRoy Lad Panek’s Watteau’s Shepherds: The Detective Novel in Britain (1979) and Martin Edwards’ Golden Age of Murder (2016), The Story of Classic Crime in 100 Books (2017), and The Life of Crime: Detecting the History of Mysteries and Their Creators (2022). See also Mike Grost’s encyclopedic site A Guide to Classic Mystery and Detection.

For another good example of Golden Age misdirection appropriated in cinema, see this entry on Mildred Pierce.

Perplexing Plots is available for pre-order here and here. This is a good place to thank Sarah Weinman and Yuri Tsivian for their favorable comments on the book, which are available on these sites.

P.S. 9 August: I now realize I neglected to mention that Joni’s daughter Meg isn’t as harshly characterized as the rest of the Thrombey clan. She’s a friend to Marta and Fran and seems genuinely to care about Marta’s fate. However, she’s still a pothead who walks out of her benefactor’s birthday party and who colludes with the family to call Marta to get information. In plot terms, she’s one more threat to Marta.

Although we didn’t discuss this point, I thank John Toner of Renew Theaters for amiable correspondence about Knives Out.

Knives Out (2019).

Figuring out MEN

Men (2022).

In an earlier entry I considered films identified as “prestige horror” and traced how the idea developed among critics and journalists in the mid-2010s. That entry was written just after I saw The Northman, Robert Eggers’ next film after The Lighthouse; it was also the first of four films being released this year and early next year, each directed by one of the four directors generally identified with the trend.

Now Alex Garland’s Men has quietly come and gone, at least in theaters. I write this a few days after distributor A24 showed a double feature of Men and Ex Machina, available for one day only, on their occasional “Screening Room” streaming series, which was launched om response to the pandemic with Minari on February 12, 2021.

Seeing Men a second time made it possible for me to take notes and get a better grasp on the complex and oblique narrative of the film. That narrative has apparently perplexed most critics and audiences, resulting in considerable annoyance. I could follow it reasonably well, and I understood what happened at the end on first viewing–a particularly annoying section for the perplexed. This second viewing confirmed that I had been right about the ending, though I find that it was set up even more carefully than I had noticed.

At first I thought I should wait until Men arrived in a more conventional continuous streaming fashion. In preparing this entry, though, I learned that the DVD and Blu-ray release date has been announced as August 9. No subscription streaming date has been announced, although one can now buy the film from several providers for $19.99. Kudos to A24 for committing (so far) to bringing out all its films on physical media as well as streaming.

So my timing may not be too premature, but I realize that many will not have had a chance to see the film yet. I should emphasize that there are major spoilers ahead. I am going to reveal what happens at the end in some detail, as well as analyzing the imagery in the film and making a stab at what it’s all about.

Challenging films

Before I launch in, I would like to say something about highly unconventional films that defy our expectations. Increasingly I read adverse reviews of such films. They seem to have upset the writer by not turning out to be what he or she expected upon entering the theater. I first noticed this response in watching László Nemes’s Sunset (2018) for the first time. Within ten minutes I was baffled but excited at the prospect of what was obviously a masterpiece. Despite my puzzlement, I think I got the gist of it and certainly sensed what Nemes was doing stylistically. I was startled to read the professional reviewers’ mostly negative notices, seemingly based on annoyance at being puzzled. Having the chance to see Sunset a second time on a screener, I understood it better and wrote up an analysis of it.

I’ve seen this sort of thing happen occasionally since, notably with Leos Carax’s Annette last year. I don’t think it’s Carax’s best film or as challenging as Sunset or even Men, but it deserved better than it got from a lot of reviewers.

I would assume that the duty of anyone writing about a film for publication, particularly one who gets paid to do so, is not to judge a film by whether it conforms to the expectations he or she brought into theater. If a film is challenging in the way these examples are, the obvious strategy is to try and figure out what the film is trying to do. How and why is it puzzling or unconventional? I remember that one professional critic who shall remain nameless wrote that she wanted to like Annette but wasn’t able to. I would say that the critic’s duty is not to like or dislike a film. That’s the realm of buffs reviewing on Facebook or Google or wherever. The critic’s duty is to understand it, to figure it out, or at least to make the attempt. I realize that such films really need to be watched a second time to get a better grasp on their strangeness, but even on a first viewing one can usually discern that a second viewing is worthwhile, and why.

Of course, trying to figure a film out may lead one to conclude that it really is bad. Maybe it’s not experimenting in original ways or it’s using flashy style gratuitously. But if the viewer does figure it out and it’s good, even a masterpiece, he or she has discovered something–a process that I find rewarding and pleasurable, whether or not I ultimately don’t much like the film.

I’m not claiming that Men is an undying masterpiece, though I do admire it more than many do. The point is that a significant number of adverse reviews reflect the same sort of unwillingness to engage with the film’s unconventionality.

This unwillingness makes me wonder what happened to the sort of openness to originality and even occasional experimentation that existed from the late 1940s, for several decades, when such films as Voyage to Italy, Hiroshima mon amour, 8 1/2, Pickpocket, Persona, Death by Hanging, and other unconventional films of the golden age of art houses. Would such challenging films be hailed and become long-treasured classics? I hope so, but …

The final and only girl

Again, I’m not going to point to particular reviewers, but many have gone for the obvious and describe the film solely in terms of the misogynistic males. Are all men misogynistic?

I do think that the title was a big mistake, inevitably egging critics on to batten onto the toxic masculinity displayed by all the male characters as the the obvious, straightforward point of the film. In that case it would be pretty simple and overly obvious. I think the form and style of the film make it more complex than that. I suspect that critics thought of the film as a sort of social commentary first and a horror film second. This may be one of the disadvantages of prestige horror. To some extent the films can be seen as art cinema rather than regular horror pictures, and therefore ripe for interpretation rather than analysis as horror films. In fact they seem to be a combination of art and genre types.

But however arty, Men is a horror film. The villains of horror and especially slasher films tend to be grotesque, often wearing masks and wielding chainsaws and the like. It’s a well-established convention. From at least Psycho on, these villains are seen as madmen, deviants, not representatives of the traits of an entire gender. They are basically monsters, some endowed with supernatural traits, as are the male characters in Men.

In struggling to figure what Garland was up to in Men, about halfway through it dawned on me that he had neatly reversed the “final girl” plot. This common structure in the slasher sub-genre of horror films was formulated by Carol Clover in her Men, Women, and Chainsaws: Gender in the Modern Horror Film (1992). Her insights have become common currency in the field, with “final girl” having its own Wikipedia entry. A crazed killer picks off a group of victims, often a bunch of male and female teenagers, in a shooting-gallery narrative. Clover points out that typically only one, usually a girl or woman, manages to survive and kill the group’s nemesis.

Men does exactly the opposite. There is a set of male villains, mostly characterized as simply obnoxious at first and becoming increasingly dangerous until they are revealed as murderous, supernatural monsters. (Samuel’s incongruous blonde female mask may be a reference to those worn by such villains.) There is no group of victims, no final girl, just the only girl, who manages to wipe them all out.

Harper is, to be sure, initially seen as a victim, pursued by the Naked Man early on and ultimately by Geoffrey, who tries to run her down in her own car before crashing it. (None of the village men apart from Geoffrey and the little boy, Samuel, is given a name. “Naked Man” seems to be what people use for him.) She is terrified in many scenes and forced to retreat to her rented house, which proves inadequate to keep these guys out. Occasional shots of her in the house are seen through the large windows, as if from a lurking villain’s point of view–a common convention of slasher films.

At one point she is nearly defeated, declaring to her friend Riley that she will give up her vacation and leave, though she seems more angry than frightened. Riley urges her to stay, however, and Harper fights back–ultimately successfully.

I’m not sure Garland is the only filmmaker to create such a reversal of this widespread convention. David and I happened to watch Edgar Wright’s Last Night in Soho (2021) recently, and one might say that something vaguely similar is going on. Again one woman wreaks her revenge on a series of monstrous males. There may be other such films, but I think Men is a particularly original and clever example.

They don’t call it Mother Nature for nothing