Archive for the 'Movie theatres' Category

Dispatch from another 35mm outpost. With cats.

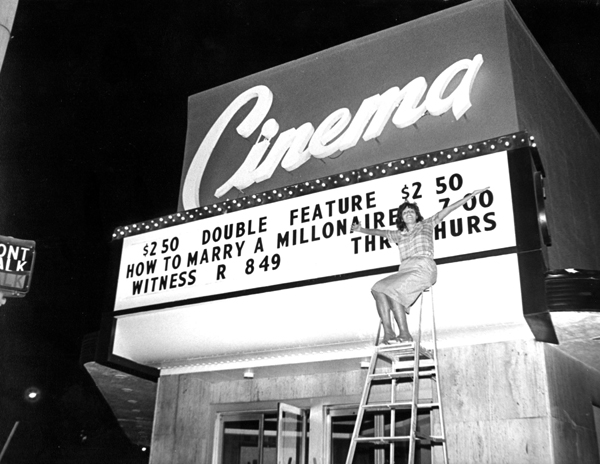

Cinema Theater, 1985, with JoAnn Morreale.

DB here:

For a while now I’ve been tracking the consolidation of digital cinema. After a blog series, I melded the entries with other information and created the e-book Pandora’s Digital Box. (To the readers who bought it, thanks!) Last year, in a blog called “End Times” I updated the information. Now we’re at post-End Times, I suppose.

David Hancock, who keeps meticulous account of these things, issued an IHS Technology Profile report on the state of things at end 2013.

*Of the world’s nearly 129,000 screens, over 112, 000, or 87%, are digital in some format. Most screens are compliant with the Digital Cinema Initiative standard used in the US, but India has pioneered the cheaper “electronic cinema” formats. Many of these e-screens will upgrade to the DCI standard.

*The UK and France have fully converted, along with most smaller European countries. Those countries benefited from various degrees of government support for the conversion.

*China now contains over half of the 32,642 digital screens in Asia.

*High concentrations of 35mm venues remain in Egypt, Morocco, Greece, Portugal, Ireland, and other areas with economic troubles. Other analog countries, such as Slovakia and Slovenia, lack public funding and contain mostly single-screen venues. The more multiplexes a country has, the greater the pressure to go DCI.

*In North America, out of about 40,000 screens, close to 93% have converted. That leaves about 3200 analog venues. It’s hard to know how many of those have closed or will close soon.

Most of the surviving analog sites, I suspect, are subsequent-run, like the five 35mm screens at our Landmark/Silver Cinemas ‘plex. And our Cinematheque and student-run Marquee continue to find and show excellent film prints. But clearly the moving finger has written. We at the University are striving for funding to make the changeover.

So too is a wonderful cinema I visited back in January. A family trip carried me back to my stomping grounds in New York’s Finger Lakes. I’ve already retailed some information about my hometown cinema, and a 1915 film that was discovered there. For now, let me tell you about a theatre I visited during a few days in Rochester.

Let George do it

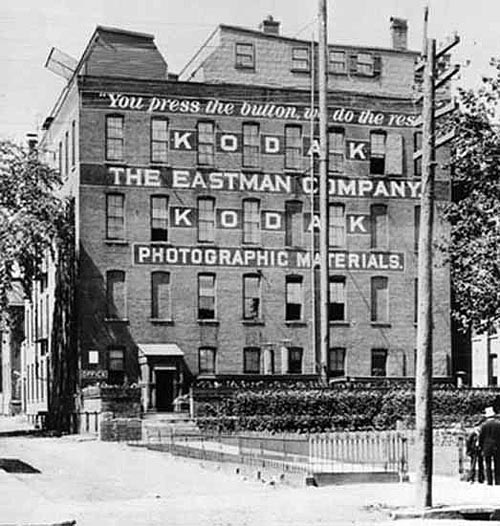

Eastman Company, 1892.

Before there was Hollywood film production there was New York film production. Before that, there was West Orange, New Jersey, where Mr. Edison and Mr. Dickson devised a movie machine. And somewhat before that, before movies themselves, there was Rochester.

Rochester was the home of the George Eastman company, founded in 1880. Eastman pioneered consumer still photography; he made up the word “kodak” to suggest the click of the shutter button. The company manufactured the flexible 35m film stock that formed the basis of the American cinema industry. Another Rochester industry, the venerable Bausch & Lomb provided camera and projector lenses, including those for CinemaScope in the 1950s.

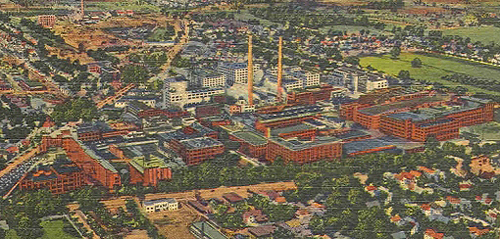

I suppose most people under thirty have never used a film-based camera, and for them the firm’s cheery yellow-and-red logo looks the way an ad for Packards looked to me in my teen years. Throughout most of the twentieth century, though, Eastman Kodak was one of America’s great technology firms. Here’s the Kodak Park facility ca. 1940.

The firm’s tragic decline will eventually get book-length treatments, but a short version is here.

Despite having invented the first digital camera, Kodak was overwhelmed by faster-moving competitors in that realm. As the firm mounted huge losses, the CEO, Antonio Perez, sought to leverage cash through Kodak’s many patents, but that tactic couldn’t stave off disaster. By 2011 Kodak stock was selling at about $1, down from the $25 it had been at when Perez arrived. In the same year, he was appointed to President Obama’s Council on Jobs and Competitiveness. Kodak filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy in the following year.

Kodak has tried to reinvent itself, but its collapse has damaged Rochester badly. Growing up, I encountered in Kodak a supreme example of paternalistic capitalism; George Eastman even paid for dental care for all of Rochester’s children. In the 1980s over 60,000 people in Rochester worked at the firm; now fewer than 7,000 do. As the company imploded, its pension funds fell behind. During my stay I met former employees who had counted on a secure retirement and are now struggling to make ends meet. There were also plenty of salty epithets aimed at Perez, who is said to receive an annual salary of over $1 million, along with millions more in other compensation.

Some argue that Rochester as a whole is recovering. If so, it’s a slow climb.

Still, for cinephiles, Rochester remains a remarkable city. There is the historic Little Theater. It’s one of the oldest art houses in the country and now has several screens, all but one of them digital. The theatre has been taken over by the local NPR outlet and presents indie and foreign titles, along with some live music events. There’s also the magnificent Dryden Theatre operating under the auspices of the George Eastman House, one of the world’s great archives. Its programming has always been stellar, and it continues to bring rare films to the city.

Then there’s a real survivor: the Cinema Theater.

The South Wedge upstart

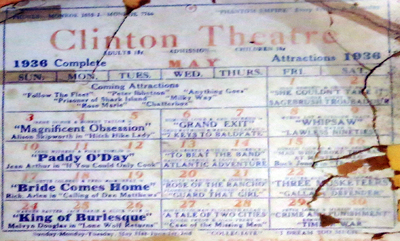

The Clinton Theatre, mid-1930s. The features are In Old Kentucky (1935) and The Return of Peter Grimm (1935).

It opened in 1914, smack in that period when motion pictures became the movies. It was initially called the Clinton Theatre because it occupies the corner of South Clinton Avenue and South Goodman Street. It offered minimal comforts. Donovan A. Shilling, in his colorful and nostalgic Rochester’s Movie Mania, tells of wooden benches and a dirt floor.

Those amenities couldn’t easily compete with the offerings of the Clinton’s more splendid rivals.

There was, for instance, the Piccadilly, opened in 1916. Advertised as a million-dollar house, the Piccadilly was built with a grand stairway and an orchestra pit for a sixteen-piece ensemble. Its auditorium could seat 1500 people in what the trade press announced as exceptionally comfortable seats. A beautiful exterior photo is here. Eventually the Piccadilly became the Paramount. Rochester was a pretty rich city then.

The Clinton closed in 1916, reopened briefly, closed again, and reopened in 1918. This time it held on. Located outside the central theatre district, in a neighborhood known as South Wedge or Swillburgh, the Clinton was a classic neighborhood second-run house. You might have to wait quite a while to see a release, which would play the downtown theatres first. But at least you benefited from a swift turnover. During one week of February 1929, you could see The Big Killing and Bachelor’s Paradise (on a double bill), Uncle Tom’s Cabin, Tim McCoy in Wyoming, The Crowd, and While the City Sleeps, starring Lon Chaney. These titles had been released in spring and early fall of the previous year.

The Clinton wasn’t part of a chain, but it hung on through Hollywood’s biggest studio years. In 1934 it was one of thirty-two Rochester theatres, some of them huge. The Century could hold 2500 people, the RKO Palace 3000. (Of course many such theatres hosted live shows as well.) With capacity of only 500 (about the same as the Little), the Clinton was in the same category as the Aster, the Broad, the Empress, the Hudson, the Lyric, the Majestic, and the Rexy. Admission was typically $.15, and that usually got you two pictures. Bills changed three times a week, with the big pictures running three days.

Surprisingly by our standards, the major films weren’t playing Friday and Saturday. I can’t prove this, but I’ve read that Sunday afternoons and evenings yielded the big audiences for neighborhood theatres–possibly because many people worked six-day weeks. (See the codicil for more information.)

But, as mentioned in an earlier entry, the late 1940s were problematic for exhibitors because attendance plummeted. In 1949, the Clinton was taken over by Jo-Mor Enterprises, a major Rochester chain. Renovated with the Art Deco façade it now has, the newly named Cinema played arthouse fare as well as subsequent-run Hollywood films.

The Cinema was headed for closure in the mid-1980s when it was saved by an unlikely heroine. Earth Science teacher JoAnn Morreale bought it and spent over $100,000 in improvements. She did everything from negotiating with distributors to cleaning toilets.

Her energy made the theatre what it had been in its heyday, a center for community activity. Locals came in with gifts and home-made treats. Some spent the day there, watching the double-feature matinee and the double-feature evening show. Six bucks got you four movies. Here’s the old beauty in 1992.

Two years ago the Cinema was bought by John Trickey. The house is still a second-run venue, but unlike most it still offers double bills. The night I visited with my sister Diane you could have seen Mandela and Gravity in one go. The prices have gone up only a little since the 1980s: $5 for adults, $3 for seniors, students, and kids under 12.

We met the Cinema’s majordomo Benjamin Tucker. By day Ben is a Curatorial Assistant at Eastman House, but he loves film history and is happy to help out the theatre.

The shows are still in 35mm, although Ben is coordinating a crowdfunding campaign to help out digital conversion.

Princesses

We met the staff, including the projectionists and the ticket lady Pat Russo, who has worked there for about ten years. She gives you real pasteboard tickets, not those flimsy, curly multiplex printouts.

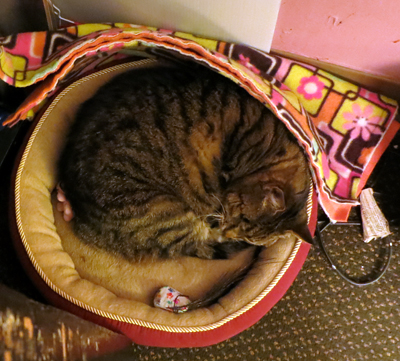

And there’s the proud lineage of Cinema Theater cats, starting with Princess to Princess the second (ruling for about fifteen years) up to Sue, who’s been in residence about six months.

The Princesses would circulate among the seats, startling patrons by rubbing up against their legs or leaping onto their laps. Sue has a habit of settling down for a snooze in the middle of the line at the concession stand, forcing customers to step over her on their way to the popcorn.

I never visited the Cinema in my salad days (the 1960s). It wasn’t playing so much arthouse fare, I think, so I tended to visit the Little or the Dryden. I wish I had sought out the Cinema. This is one of the oldest continuously operating theatres in the country. Long may it flourish.

Thanks to Ben Tucker for information and images, to Jim Healy for tipping me off to the theatre, and to Diane and Darlene Bordwell for their company.

The image of the mid-1930s Clinton comes from Shilling’s Rochester’s Movie Mania; Carl Baxter supplied the original photo. More Clinton/Cinema Theatre memories here. The Rochester Subway site hosts stupendous, recently discovered photos of the RKO and Loew’s picture palaces.

PS 16 March 2014: Alert reader Andrea Comiskey supplies some background on the Clinton’s scheduling three programs per week during the classic years.

Mae Huettig (Economic Control of the Motion Picture Industry, 1944) says that only theaters that did not have to block-book (majors’ affiliates, members of large chains, etc.) got to choose films’ playdates. Whether this was really as absolute as she makes it sound, who knows? But what this means for when the “best films” (typically the A pictures) would tend to appear is tough to determine. On the one hand, you could imagine that distributors would want the strongest, most appealing films showing on the weekends when they could bring in the biggest crowds. On the other hand, you could imagine distributors trying to force underperforming/weaker films onto bills on the busier days since there’d be higher baseline business regardless of the merits of the films on the program. Exhibitors that didn’t get to pick playdates certainly did complain.

In an interview published in Kings of the B’s, (1975) Monogram’s Steve Broidy says that Saturday is the busiest day, at least for small-town exhibs. He also says that these exhibs liked flat-rate rentals on Saturdays so they could run up the profits and echoes the idea that the particular film didn’t matter a ton since people were going out to the movies regardless.

As was the case with your Rochester example, theaters that changed programs 2 or more times a week (which, at least in big cities, were more likely to be sub-run houses) often split the weekend days across two programs, with many theaters adding an extra feature exclusively for the Saturday kiddie matinee. I’ve seen just about every possible permutation, but for a twice-weekly changeover, Sun-Wed & Thurs-Sat was a pretty common pattern. For thrice-weekly, Sun-Tues, Wed-Thurs, & Fri-Sat was common. But I’ve also got plenty of examples of theaters that showed the same program Sat. & Sun.

Andrea is writing a dissertation about distribution and playdate patterns in the 1930s. I’m happy to get her clarification here, which shows, as usual, that film history is always more complicated than it seems at first.

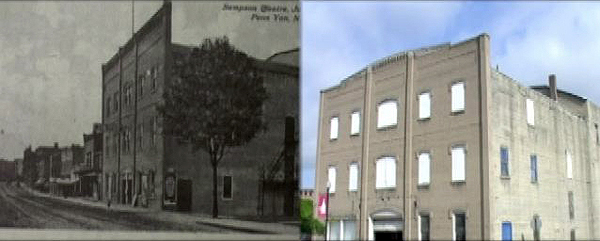

The Cinema, 2014. Photograph by Darlene Bordwell.

You can go home again, and maybe find an old movie

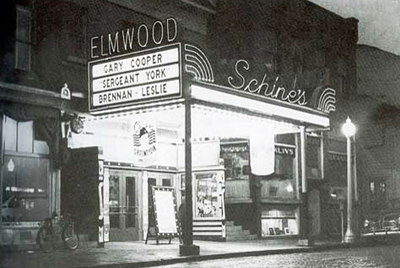

Schine’s Elmwood Theatre, Penn Yan, New York, late 1954-early 1955. Photo courtesy Yates County History Center.

DB here:

Nowadays when a theatre closes or goes digital, it says farewell by screening The Last Picture Show. That hadn’t yet become a tradition when the Elmwood Theatre of Penn Yan, New York presented Bogdanovich’s movie on its final day in November 1972.

Six people showed up.

The Elmwood had been going downhill for years. “I think the theatre building is an eyesore,” declared the chairman of the town’s Urban Renewal Agency. Once part of the powerful Schine circuit, the theatre had been acquired in the mid-1960s by the Rochester-based Panther chain, later renamed Countrywide. That firm seems to have specialized in low-budget genres and X-rated fare. In Penn Yan, the UR officer declared, most of the Elmwood’s programs were rated “restricted,” adding: “Yet it is claimed by some that it is a recreational facility for our children.” Disney films were screened at the Elmwood during those years, but local moviegoer Robert Brainard noted: “They were getting all the junk and nobody was going, not even the kids.”

When the theatre was finally closed, it stood vacant. Vandals broke the windows, and pigeons roosted inside. It had come a long way from the 1940s.

In 1974, two businessmen paid $11,000 for the building and turned it into a racquet club. That business operated for some years, but in 2003 the entire structure was demolished and a new village hall was built on the site.

By then a small three-screen mall cinema had set up business elsewhere in town. I report on a visit here.

In January, I was back in Penn Yan and naturally I sniffed around. Thanks to John H. Potter and Lisa M. Harper of the Yates County History Center, and my sisters Diane and Darlene, I came away with some precious information about the theatre I attended for the first eighteen years of my life.

I also came away with an extremely rare film.

Broadway Melodies and Cherry Blossom Queens

Captain Harry Morse ran steamboat trips on Lake Keuka. He was a legendary figure. Some said that as a boy he had caught a lake trout on his nose. (I know: How could you do that? Supposedly he bent over the side of a boat and a trout leaped up and glommed on.) More prosaically, Morse invested in Penn Yan movie houses, and in 1920 he bought the Shearman House Hotel, a popular stopover for visiting vaudevillians. Morse turned the Shearman House into a theatre.

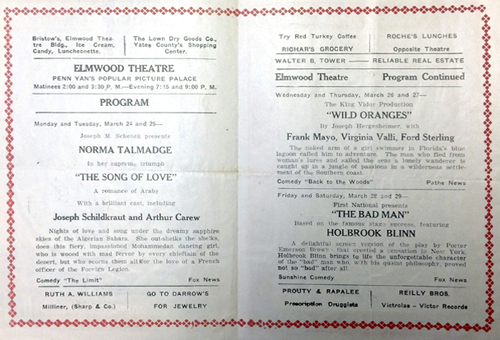

The Elmwood Theatre opened in 1921. It held at least 700 people. That’s pretty big for a town of 4500 people, but as the county seat and a business center, Penn Yan brought in farm families. Many shows were accompanied by printed programs listing coming attractions and carrying advertisements for local businesses. This one, for Song of Love, is from 1923.

Admission was typically 11 cents for matinees and 17 cents for evenings. “Specials” like Chaplin’s The Kid boosted ticket prices to 17 and 28 cents. In 1936 the Schine chain acquired the house.

The Elmwood benefited from the projection expertise of Nathaniel P. “Nat” Sackett. Nat had begun his film career in 1908 at another local movie house, vocalizing with the song slides shown between reels. He became a projectionist before joining the Elmwood in 1923. He stayed on for several decades. According to Nat, The Broadway Melody was the first sound film the Elmwood played. During World War II, he worried that too many theatres were running triple features. If the fad continued, production couldn’t keep up. For Penn Yan, one feature was good enough—especially if it was something like How Green Was My Valley or Captains of the Clouds.

A small-town movie house often became a community center. Elmwood patrons remember talent shows and holiday parties, with gifts and contests before the screenings. In 1940 a housewife attending I Love You Again could join an hour-long cooking class (with prizes) just before the show. Young women would be named Apple Blossom Queen or Cherry Blossom Queen. Halloween screenings included costume contests and of course sudden blackouts and scary sound effects. During the war, with no television or Internet, people flocked to the theatre for newsreels. Customers were steered in and out by ushers; the Elmwood employed them well into the 1950s.

“Today,” remembered Nancy Gillette, “most people cannot imagine a theatre as large as the Elmwood, which included a large balcony, being full most of the time.” By the 1930s, admission prices had come down a bit for children. Ten cents admitted Nancy to the Saturday marathon matinees: “Gene Autry, Hopalong Cassidy, Roy Rogers, Charlie Chan, the newsreel and one or two cartoons—WOW!” Lines of kids stretched down the block. In the 1950s, Diane and I were among them, watching the same cowboy heroes, along with Tarzan and Martin and Lewis.

Romances and marriages were forged at the Elmwood. In 1933, a young man taking tickets let a young woman slip out to retrieve the keys she left in her car. Over the next few days he began to drive by her house. Her cousin knew the young man and said, “Margaret, I am taking you out when Sam comes along, and I’ll stop his car and introduce you to him.” After two years of dating, Margaret and Sam married and eventually had three children. The Elmwood manager gave Sam’s mother and Margaret free passes.

Local kids like Sam found good work at the theatre. Being an usher got you free movies and a chance to flirt with the concession girls and those who came “solo.” After movies there was pizza at the Den below the theatre. But among the ushers’ tasks was the very onerous one of changing the marquee. Jerry Nissen remembered:

First you had to do layout on paper what the marquee was to say. Then, working from the last letter in the last row, fill a heavy wooden box until you get to the first letter of the first row. The solid metal letters were stored in the basement and you hauled them up to the street. Now imagine, if you will, climbing a rickety old step ladder in the rain or snow and taking down the old message and then letter by letter placing the new message on the two-sided marquee. Brrrr, it used to get very cold. Also on occasion we were the targets of some nice vocal comments and snowballs coming from the T & C Tavern across the street.

DIY movies, 1915

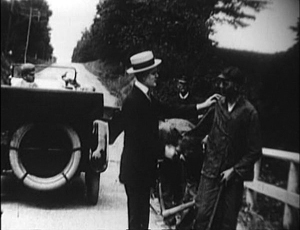

Wheat and Tares (Penn Yan Film Corporation, 1915).

Penn Yan had theatres before the Elmwood went up. In the ‘00s and ‘10s Nat Sackett sang at Theatorum and another theatre, both owned by the Wickham brothers. For a time Nat took over ownership of them. Before Captain Morse built the Elmwood, he was showing movies at the old Sampson legitimate theatre, as well as in the Cornwell, located above a department store. The town apparently had four screens in 1911.

With so many films playing within a couple of blocks, it’s perhaps not surprising that a local businessman decided to make one of his own.

Edward R. Ramsey owned a local paper mill and a factory that manufactured electrical cable. The story goes that when Ramsey observed that Hollywood, California was buying a great deal of his cable, he decided to try moviemaking. Ramsey sold his cable plant and started the Penn Yan Film Corporation.

After making some shorts, Ramsey tied his first feature production to a fund-raising effort by Keuka College. The college’s aim was to provide advanced education to rural students who couldn’t to go to a big university. Ramsey’s film would demonstrate the virtues of going to college. All the talent was local, including the cameraman, who was Ramsey’s brother. From outside, Broadway actor and occasional film director George E. LeSoir was recruited to direct the show.

Shot in the summer of 1915, Wheat and Tares traces the story of two young men. Both Jim Watson and Will Beggs read dime novels, but Jim is encouraged by Alice Corwin, daughter of a Penn Yan businessman, to improve himself. Uplifted by literature, Jim leaves the farm for Keuka College. There he learns enough to become an auto salesman. At the same time, Will (who stuck to pulp fiction) falls in with a gang of layabouts and petty crooks. Their fates converge when Jim discovers oil. A crooked realtor hires Will to put Jim out of action long enough for the site option to expire. But Alice renews the option, and Jim’s family becomes rich. Meanwhile, Will’s life of crime catches up with him, and he is sentenced to a prison road gang. Jim and Alice, now married and with a child, stop when they see Will on the road. Jim vows to help his old friend go straight.

Despite its opening-night success at the Sampson playhouse, Wheat and Tares didn’t have legs. Keuka College closed in fall 1915 and didn’t reopen until 1921. Ed Ramsey died in an auto accident in June 1916. The film may have gotten no distribution outside the region. Stored in the Ramsey home, it was discovered decades later when the house was prepared for demolition. The film was transferred to safety stock and eventually to DVD. That’s the version I have seen.

In the moralizing manner of its day, the full title, Wheat and Tares: A Story of Two Boys who Tackle Life on Diverging Lines, contrasts the life paths of its two protagonists. A tare is a form of weed that infects a field of healthy wheat. Tares in their early stages look very much like wheat, so the metaphor implies that one must wait to see if a young man will turn out well or not. (The Biblical reference is a parable by Jesus, at Matthew 13: 34-35.)

The surviving copy of Wheat and Tares has lost its opening reel. What remains is a fairly ordinary 1915 film. The parallel stories of Jim and Will aren’t developed in tandem; we lose Will for most of the film. A great deal of the second reel is occupied with rich boys hazing Jim at college, which does teach him the manly art of self-defense, but to no special point: he doesn’t get to use his boxing skills later. Another undeveloped plot line involves a movie company filming in the vicinity.

Theme and plot don’t match very well. If you are trying to convince people that going to college will better them, why show your hero succeeding by stumbling onto an oil gusher? Jim would have been just as likely to find oil if he had stayed a sodbuster. The climax is particularly feeble: While Jim is recovering from the beating given him by Will and another thug, it’s Alice who saves the day. She does this not through extraordinary courage or sacrifice, but simply by having her father write a check that renews the option. The realtor, a very passive villain, does nothing, underhanded or otherwise, to block her maneuver.

Stylistically, you can hardly expect The Birth of a Nation, The Cheat, or Regeneration from this tiny Finger Lakes company. In most respects, the film resembles standard films of the period. Some filmmakers were exploiting the sort of crosscutting popularized by Griffith, but Ramsey and Le Soir take almost no advantage of it. There’s no fast cutting to pick up the pace. Most scenes are played in single shots, with close-ups used only to emphasize details, such as a deck of cards, that can’t be easily seen in the master framing. The closest shots of the principals occur during a phone conversation–again, a convention of the period.

Nor does the film exploit the sort of complicated staging we find in tableau cinema. There is one rather well-handled crowd shot, as well as a smooth track-in and-out when Will recruits a one-eyed thug to help him ambush Jim. Simple camera movements like this were by 1915 considered a fairly normal option.

There is an ambitious matte effect when Jim and his college chum Phil visit the movies, but even this fairly common device is somewhat bungled when the boys’ bodies become ghostly by crossing into the matte area.

Although Wheat and Tares exemplifies ordinary cinema of that day, like most films of the first great era of cinema it’s a pleasure to watch. Shooting on location yields spontaneous beauties. At one point Jim rides home on the trolley. In a film utterly lacking in calculated lighting effects, we get a lovely image. Not only do we see the town and wagons pass through windows, but after Will and his partner jump aboard, accidents of backlighting turn them into sinister shapes.

Trolley shots are among the glories of 1910s cinema; I don’t think I’ve ever seen a bad one.

Penn Yan must have been gorgeous then, with the main streets lined with elms.

The trees were felled by Dutch elm disease and other factors, I’m told.

As with any film shot in surroundings that you know, part of the fun comes in spotting familiar locales. John Creamer’s introduction juxtaposes some town landmarks. Here’s the Sampson Theatre, then and now.

Two locations that my sisters discovered pop up late in the film. For a chase, the camera was set up just around the corner from Ramsey’s house.

Ramsey’s house was demolished to add a building and a parking lot to the local hospital, but from that vantage point, we found the source of another shot. The camera was apparently set up in front of Ramsey’s home to frame Jim and Alice and their child in their chauffeur-driven Maxwell. The sidewalk in the foreground is gone, but the background area, including the fire hydrant, has stayed surprisingly constant.

And whatever the faults of Wheat and Tares, watching it gives you a glimpse of the entrance to Captain Morse’s Sampson Theatre (below). In the summer of 1915, Charlie Chaplin had sauntered into my home town. The show starts on the sidewalk, as they used to say.

I’m grateful to John and Lisa of the Yates County History Center for all their suggestions, for access to their files, and for the exterior photo up top and the shot of the Elmwood interior. You can read the local newspaper’s announcement of the Wheat and Tares premiere, with a teaser synopsis, here. Thanks also, of course, to Darlene and Diane. The picture of Penn Yan’s town hall was supplied by Darlene, whose photography site is here.

A DVD copy of Wheat and Tares is available for $15 from the Yates County History Center. You can email Lisa M. Harper, ycghs at yatespastdotorg, or call (315) 536-7318. Credit cards accepted.

The indispensable guide to the theatres in this region is Norman O. Keim’s Our Movie Houses: A History of Film and Cinematic Innovation in Central New York (University of Syracuse Press, 2008). You can read about the Schine chain there, or here.

Wheat and Tares is a prime example of an orphan film. Dan Streible of NYU is a moving force behind retrieving and restoring these elusive items, and a new Orphan Film Symposium is coming up in Amsterdam.

Wheat and Tares (1915). The sign on Charlie’s crotch reads” “Meet Me at the Sampson Program.”

The book stops here: Theory, practice, and in between

Tinpis Run (Pengau Nengo, 1991).

DB here:

Apart from things I’m reading for research (academic monographs, 1940s Hollywood novels, star bios and autobios), the film books I like best are blends. They bring together information, ideas, and opinion. I learn some facts about films and their contexts. I encounter some concepts that illuminate those facts. And I get introduced to some arguments about the best way to understand the information and ideas. In my ideal world, the blend winds up answering some questions—maybe questions I’ve thought about, maybe ones that never occurred to me.

I especially like books that have one foot, or toe, in filmmaking practice. The poetics of cinema I try to practice is, from one angle, an effort to grasp the principles underlying filmmakers’ creative choices. Sometimes those choices are announced by the filmmakers; sometimes we have to reconstruct them on the basis of the films and other data. So for me a drastic split between theory and practice isn’t very informative.

These pronunciamientos are but prelude some comments on books that push several of my buttons. Maybe they’ll do the same for you.

Philosophy goes to the multiplex

Stagecoach (1939); True Grit (1969).

What book brings together Cézanne and Tony Soprano, Gregory Peck and Simone de Beauvoir, Plato and South Park, The Twilight Zone and Wittgenstein?

Okay, I know the answer: Practically every book by a littérateur convinced that Great Big Theory gives you a way of talking authoritatively about anything, especially pop culture. So I rephrase my question: What book brings together these and many more items with care, rigor, and infectious amusement?

That narrows the field quite a bit. A strong candidate is a book that has chapters like “What Mr. Creosote Knows about Laughter,” “Andy Kaufman and the Philosophy of Interpretation,” and “The Fear of Fear Itself: The Philosophy of Halloween”— not the movie but the holiday itself.

The short answer to my question: Noël Carroll’s new collection of essays, Minerva’s Night Out: Philosophy, Pop Culture, and Moving Pictures.

Noël Carroll isn’t merely the most important philosopher ever to write about popular culture. He has been for decades a major force in film theory and criticism, as well as a philosopher making contributions to moral and legal theory, historiography, and a welter of other areas. His fertile mind and prodigious typing skills have combined to produce over fifteen books and a list of articles running to triple digits.

It’s not just quantity, of course. For those of us in media studies, Carroll has been the most well-informed and adroit analyst of trends in film theory. His Philosophical Problems of Classical Film Theory (1988), Mystifying Movies: Fads and Fallacies in Contemporary Film Theory (1988), and Post-Theory: Reconstructing Film Studies (1996, coedited with me) have proven enduring contributions to the debates about the best ways to understand the nature and functions of cinema. He is, as you can tell, a controversialist. Like all good philosophers, he’s devoted his life to getting the ideas right. Over the same period, Carroll has proven himself a wide-ranging practical critic, discussing classic silent films (especially comedy), modern avant-garde work, and Hollywood movies from the 1930s to the most recent releases. This isn’t to slight his important work as a dance and television critic as well.

It’s not just quantity, of course. For those of us in media studies, Carroll has been the most well-informed and adroit analyst of trends in film theory. His Philosophical Problems of Classical Film Theory (1988), Mystifying Movies: Fads and Fallacies in Contemporary Film Theory (1988), and Post-Theory: Reconstructing Film Studies (1996, coedited with me) have proven enduring contributions to the debates about the best ways to understand the nature and functions of cinema. He is, as you can tell, a controversialist. Like all good philosophers, he’s devoted his life to getting the ideas right. Over the same period, Carroll has proven himself a wide-ranging practical critic, discussing classic silent films (especially comedy), modern avant-garde work, and Hollywood movies from the 1930s to the most recent releases. This isn’t to slight his important work as a dance and television critic as well.

This focus on film theory stems from the fact that Noël’s first Ph.D. degree was in film studies. But soon afterward he went on to get a second Ph.D. in the philosophy of art. His cinema research was always philosophically informed, but once he became a card-carrying philosopher, he commuted between two academic areas. He helped found the broader movement called Philosophy of Film, and he continues to write on a lot of different topics. His Humour: A Very Short Introduction is due out in a couple of weeks.

Minerva’s Night Out scans the range of his interests—not only all types of media (which he genuinely enjoys) but a variety of the philosophical puzzles they pose. These he tackles with verve, patient but not plodding analysis, and a range of references that make you wonder if this guy has seen and read pretty much everything.

Here’s the sort of thing that Noël thinks about. We all know that to enjoy a movie fully we often have to appreciate the way in which a star’s performance builds on previous roles. But there’s a problem. The fictional world of a film makes only certain types of knowledge relevant to our experience. At the center of this knowledge is what Carroll calls the “realistic heuristic,” the premise that all other things being equal, the things happening in the fiction are assumed to operate under the laws of our everyday world. Sherlock Holmes (whether incarnated by Basil Rathbone or Benedict Cumberbatch) is presumed to have lungs like the rest of us, unless we’re told otherwise. Likewise, it is true in the fiction that a room’s walls are solid, while they might in reality be fake. If I see the walls as painted sets or green-screen mattes, then I’m not responding to them as part of the story world.

The same attitude shapes our sense of the unfolding plot. Armed with the realistic heuristic, we have to assume that characters’ destinies are open, that many things can happen to them (as with us). But the principles by which a movie fiction is constructed—say, boy gets girl—aren’t part of our realistic heuristic. “What we believe is probable of a movie qua movie is radically different from what we believe to be probable in a movie conceived as a credible fictional world.” Movie lore tells us that boy will get girl, but to grasp and respond to the story emotionally, we have to feel in doubt. (Perhaps this is what people mean when they say that a mistake in the movie, or a distraction in the auditorium, takes them “out of the movie.” We’ve left the fiction.)

Similarly, movie lore connects the Ringo Kid of Stagecoach to Rooster Cogburn of True Grit (the original) because John Wayne portrays both. Yet the characters live in different, sealed-off story worlds. Ringo and Rooster have no knowledge of each other. Barring transmigration of souls, how can their connection be part of our experience of either movie as a consistent fiction?

Similarly, movie lore connects the Ringo Kid of Stagecoach to Rooster Cogburn of True Grit (the original) because John Wayne portrays both. Yet the characters live in different, sealed-off story worlds. Ringo and Rooster have no knowledge of each other. Barring transmigration of souls, how can their connection be part of our experience of either movie as a consistent fiction?

Carroll comes up with an ingenious explanation. Movies summon up star personas in the manner of allusions. Just as our experience is enhanced when we see a movie refer to another movie—Carroll’s example is a citation of Rocky in In Her Shoes—so do our mind and emotions respond to the presence of the star, as either a continuing allusion throughout the film or a one-off one, as with a cameo or walk-on. As he often does, Noël points out that practicing filmmakers use the concepts he elucidates. “Allusive casting” became part of the 1970s trend of paying homage to old Hollywood, but even in the studio era it wasn’t unknown. Carroll points to The Bigamist (above left), in which somebody says another character looks like Edmund Gwenn. Of course said character is played by Edmund Gwenn.

I’ve shrunk down Carroll’s line of reasoning to give you the flavor of the way he thinks. His piecemeal approach to theory focuses not on loosely named topics but specific questions. For example:

What if anything justifies us talking about popular culture as all one thing?

How do fiction films engage us in the emotional lives of their characters? Hint: It’s not through identification.

What makes us laugh at Mr. Creosote, rather than be horrified or disgusted by his vomit-laced gluttony?

How does a tale of dread, such as Poe’s “The Black Cat,” differ from a horror story?

Why should we care about Tony Soprano, who barehanded commits “crimes of which I don’t even know the names”?

Are the feelings awakened by art akin to friendship?

What role do moral emotions, such as the sense of community, play in our response to characters?

As for the jokes, they’re not of the esoteric academic type but rather straight-out funny. Just one essay, on the vague/implausible (you pick) notion that modernity (traffic, window displays, lotsa flashing lights) changed the very faculty of human perception:

The human eye rarely fixates; saccadic eye movement is the norm. We did not suddenly become attention-switching flâneurs in the late nineteenth century; we have been natural-born flâneurs since way back when.

No amount ot cultural conditioning will succeed in making normal viewers worldwide literally see human faces as cross-sections of centipedes.

I’m sure he’d give any indie filmmaker the rights to make Natural Born Flâneurs.

Viewers and their habits

Natsukawa Shizue in Town of Hope (Ai no machi, 1928).

Carroll tries to figure out certain logical conditions on spectators’ experience in general. That’s one province of film theory. But he’s also sensitive to the constraints on those conditions, the ways that historical and institutional circumstances can shape how viewers watch movies. (That’s part of the star-as-allusion argument.) Other researchers, historians by trade but sensitive to theoretical implications, have tried reconstructing the activities of theatres, trade personnel, and audiences in particular times and places.

A good cross-section of approaches has just appeared from Karina Aveyard and Albert Moran. Their anthology Watching Films: New Perspectives on Movie-Going, Exhibition and Reception contains 22 chapters of empirical research spread across the Europe, New Zealand, Australia, and the U.S. The researchers take us to particular cities and towns (Antwerp, Nottingham, and the Scottish Highlands) and to various points in history, from the 1920s to the present, passing en route the arrival of TV and the effects of the VHS revolution. There are also considerations of early reception theorists like Barbara Deming, along with studies of fan activities in Italy and elsewhere. Altogether, you couldn’t ask for a more enticing sampler of contemporary strategies for studying how audiences interact with cinema. Multiplicity long preceded the multiplex.

A good cross-section of approaches has just appeared from Karina Aveyard and Albert Moran. Their anthology Watching Films: New Perspectives on Movie-Going, Exhibition and Reception contains 22 chapters of empirical research spread across the Europe, New Zealand, Australia, and the U.S. The researchers take us to particular cities and towns (Antwerp, Nottingham, and the Scottish Highlands) and to various points in history, from the 1920s to the present, passing en route the arrival of TV and the effects of the VHS revolution. There are also considerations of early reception theorists like Barbara Deming, along with studies of fan activities in Italy and elsewhere. Altogether, you couldn’t ask for a more enticing sampler of contemporary strategies for studying how audiences interact with cinema. Multiplicity long preceded the multiplex.

A similar approach, but focused with razor acuity on a single country and period, is Hideaki Fujiki’s Making Personas: Transnational Film Stardom in Modern Japan. This book is an expedition into a nearly sunken continent, Japanese film of the silent era. Frustratingly few films have been preserved from those years, but paper documents abound. Fujiki has made intense use of them to answer the question: What were the cultural causes and results of the early star system in Japan?

The answers are rich and detailed. The very first stars weren’t on the screen at all; they were the benshi who narrated the silent program. Hideaki goes on to trace the career of the paradigmatic male star, Onoe Matsunosuke, and to show how his main traits (virtuosity and stature as “great man”) were reinforced by a troupe-based business model. Later chapters focus more on female stars, with emphasis on the influence of American actresses like Clara Bow. The flapper figure shaped not only Japanese female performers but women in real life.

Fujiki traces in some detail how the “modern girl” or moga floating through Ginza owed a good deal to Hollywood movies. He makes good use of what films survive from this period, particularly The Cuckoo (Hototogisu, 1922) and Town of Love (Ai no machi, 1928). In-depth analysis of the star image Natsukawa Shizue, above, allows him to discuss fan culture and movies’ role in accelerating trends in fashion and advertising. In all, Making Personas is a fascinating consideration of stardom as both an industrial and social construction in one of the world’s most important national traditions.

Education and environment

Institutions of another sort feature in two impressive books from the prolific Mette Hjort. She has had the very good idea of assembling documentation about how film schools work. How do different schools, academies, and more informal agencies understand the craft of filmmaking? What ethical values and social commitments are brought to the classroom and enacted in the production process? What are the histories of film schools around the world?

The answers come in two packed anthologies, The Education of the Filmmaker in Africa, The Middle East, and the Americas, and The Education of the Filmmaker in Europe, Australia, and Asia. From these we learn of the creative practices put into action by institutions in Nigeria, Palestine, Denmark, the West Indies, China, Hong Kong, Vietnam, Sweden, Germany, Australia, Japan, and many other localities. We get a real sense of intercultural communication and its breakdowns. Rod Stoneman points out that Tinpis Run, Papua New Guinea’s first indigenous feature, demanded postproduction discussions when outsider viewers couldn’t distinguish the villages presented in the story.

Things happen in these places that would astonish students at UCLA and NYU. Hamid Naficy tells of taking his Qatar students to Tanzania, where they worked on research projects only after spending the morning doing clerical and custodial work in schools and hospitals. We learn of children’s filmmaking initiatives in Mexico City, programs for at-risk youths in Brazil’s City of God favela, and students making photo and sound montages in Calcutta. One purpose of Mette’s collections is to remind us that film training goes far beyond getting your MFA and a showreel on a maxed-out credit card.

Hjort’s initiative, while already stimulating, ought to be continued and enriched. People are starting to understand the importance of film festivals within film culture—as distribution mechanisms, publicity arms, and in a roundabout way feedback systems shaping production. (One essay, by Marijke de Valck, points out the move by festivals toward film training.) More generally, we need to understand film education at all levels as shaping film production and film audiences.

Hjort’s introduction emphasizes that institutional politics are always related to larger political and cultural concerns. Social implications of filmmaking are brought to the fore in another emerging area of research. As each day seems to signal a new ecological disaster, it’s timely that a critical school has emerged to track how films and TV represent our relation to nature and technology. Among the scholars working prolifically in this area are Robin L. Murray and Joseph K. Heumann.

Hjort’s introduction emphasizes that institutional politics are always related to larger political and cultural concerns. Social implications of filmmaking are brought to the fore in another emerging area of research. As each day seems to signal a new ecological disaster, it’s timely that a critical school has emerged to track how films and TV represent our relation to nature and technology. Among the scholars working prolifically in this area are Robin L. Murray and Joseph K. Heumann.

Their first book, Ecology and Popular Film: Cinema on the Edge argues that apart from films like An Inconvenient Truth, which wear their green politics on their sleeve, there’s a much bigger and broader tradition of films about humans and the environment, ranging from fictional films with explicit messages, like Happy Feet (2006), to films with unintentional ones, like The Fast and the Furious (2001).

As “second-wave” practitioners of eco-criticism, Murray and Heumann aren’t much concerned with cheerleading or finding villains. They want to explore how media representations of the environment have responded to various cultural pressures. Their two most recent books are good examples. That’s All Folks? (2009), building on their analysis of Lumber Jerks in their first book, concentrates on American animated features. They perform careful symptomatic readings while also providing industrial context, such as the tactics by which Lucas and Spielberg adapted to the growing dinosaur craze of the 1990s.

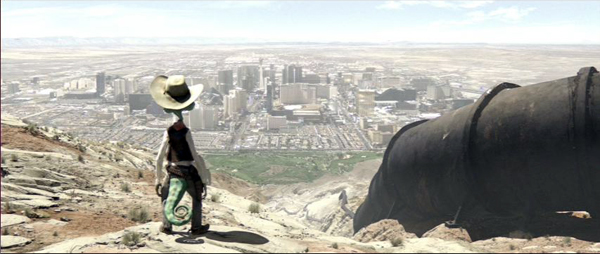

In Gunfight at the Eco-Corral (2012), Murray and Heumann tackle the Westerm on similar grounds, ranging from Shane and Sea of Grass to There Will Be Blood and Rango. Reading these chapters I was reminded how often the genre’s plots hinge on disputes over natural resources. Water, minerals, timber, grazing land, and what the authors call “transcontinental technologies” like the telegraph and the railroad are at the heart of classic Westerns, and the genre’s formulaic conflicts often have strong ecological resonance. This is the sort of criticism that refreshes your vision of movies you think know very well.

Their next book, Film and Everyday Eco-disasters is due out in June.

Things stick together

Lone Survivor (2013).

Finally, two more books merging theory and practice—but from opposite ends of the spectrum. One question that intrigues me involves coherence and cohesion in film. Roughly speaking, coherence involves the way the whole movie hangs together. If it’s a narrative film, how do the scenes or sequences fit into the larger plot? If it’s not narrative, what other principles organize the whole shebang? Cohesion involves how adjacent parts fit together—shot against shot, sequence to sequence. Both these concepts have practical implications, since every filmmaker confronts concrete choices about them in scripting, shooting, and editing.

Michael Wiese has contributed enormously to our understanding of filmmaking practice by publishing a series of books on cinema craft. The most recent one I know is by Jeffrey Michael Bays and it bears directly on cohesion. It’s called Between the Scenes: What Every Film Director, Writer, and Editor Should Know about Scene Transitions. Bays himself has written and directed films, written radio dramas (a great place to study transitions), and published books on filmmaking.

Between the Scenes is an entertaining and damn near exhaustive account of the ways that images and sounds can tie one scene to another. Bays considers aspects of space, like location or objects or actors; time; and visual graphics. The book also shows how sounds can bind scenes or emphasize sharp contrasts. In the example from Lone Survivor above, a soft whir of helicopter blades is heard over the first shot and grows louder when we move from the map to the landing area.

In a web essay called “The Hook” I explored some aspects of this process, but Bays goes into much more detail with many recent examples. He also raises ideas I never considered. For example, if we think of narratives as people traveling from one place to another (and most narratives are that, at least), then every filmmaker faces a choice: Show the journey or don’t show it. And if you show it, what parts and why and what does it tell us about the character? The larger point is: “Make sure you know where every character goes between every scene.” Thinking about this suggests ways to enrich your presentation, and it allows the characters—if only in your imagination—to inhabit a more fleshed-out world. Ideas like this can provoke everyone, filmmakers and film scholars alike.

Small-scale links between parts are considered more theoretically in Chiao-I Tseng’s Cohesion in Film: Tracking Film Elements. Trained in functionalist linguistics, Tseng brought her expertise to bear on film analysis. The results show a remarkable kinship between devices in language and certain cinematic transitions. Such linguistic functions as saliency (what stands out) and presumption (what can be taken for granted) are found in audiovisual texts too. For example, a shot taken over one character’s shoulder tends to lessen that character’s saliency and make another character, the one we see more clearly, more prominent.

Small-scale links between parts are considered more theoretically in Chiao-I Tseng’s Cohesion in Film: Tracking Film Elements. Trained in functionalist linguistics, Tseng brought her expertise to bear on film analysis. The results show a remarkable kinship between devices in language and certain cinematic transitions. Such linguistic functions as saliency (what stands out) and presumption (what can be taken for granted) are found in audiovisual texts too. For example, a shot taken over one character’s shoulder tends to lessen that character’s saliency and make another character, the one we see more clearly, more prominent.

This example is simple, but once Chiao-I gets going, she’s able to show how nearly every cut or camera movement can be seen as activating a unique tissue of cohesion devices. The words in a paragraph not only refer to ideas or things; they also link to other words in the paragraph and in the larger discourse. Similarly, in film, different aspects of the images and sounds stand out and adhere to one another instant by instant. Tseng’s analyses of passages in Memento, The Birds, The Third Man, and other films are accompanied by equally close studies of television commercials and educational documentaries. At the end, analysis is supplanted by synthesis, as she shows how the configurations she has pulled apart coalesce into levels that highlight characters and actions. It’s a fresh way to think about how we understand films within genres and stylistic traditions.

In effect, she’s showing the fine-grained patterns that emerge from the choices every filmmaker faces. It would be fascinating to sit in on a dialogue between Bays and Tseng, for they belong to the same community, or so I think anyhow. We’re all trying to understand aspects of cinema, and by focusing on certain phenomena rather closely, we have a good chance to understand them better.

So to the filmmaker who’s skeptical of theory, I say: We can’t think clearly without concepts, or talk clearly without terms. We need to develop rigorous ideas and arguments (i.e., theory) to understand film as best we can. But to the would-be theorist I say: Keep fastened on the look and feel of the films, and test your ideas and arguments not only against them, but against what you can find out about the craft of cinema, in all its historical implications.

I was pleasantly surprised, after I’d decided to talk about these books, to find work by Kristin and myself cited in some of them. Remaining coldly objective, however, I didn’t let these mentions diminish my praise.

Rango (Gore Verbinski, 2011).

On the more or less plausible sneakiness of one Preston Sturges

The Miracle of Morgan’s Creek (1944).

DB here:

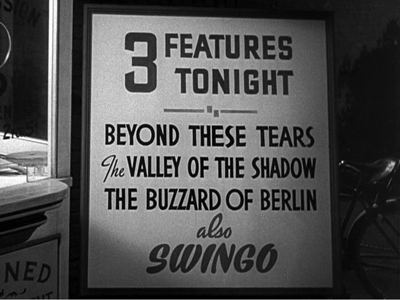

It’s no news that Preston Sturges occasionally mocked the film industry. Exhibit A is Sullivan’s Travels (1941), in which a director of escapist comedies decides to switch to serious social commentary. Sturges’ movie starts with a parody of a violent Hollywood climax that ends with two men plunging to their death. Next we’re told that Sullivan’s previous triumphs are Hey, Hey in the Hay Loft, Ants in Your Plants of 1939, and So Long, Sarong. At a later point we see a somewhat more somber triple feature:

“Swingo” is Sturges’ equivalent of Screeno and other 1930s Bingo-like games designed to lure audiences into theatres.

These gags are pretty straightforward. While working on my book on Hollywood in the 1940s, I found that The Miracle of Morgan’s Creek (1944) offers us something less obvious and more peculiar.

Three big fake features

Norval Jones (Eddie Bracken) has taken Trudy Kockenlocker (Betty Hutton) out on a date. They’ve told her highly combustible father (William Demarest) they’re going to the movies. Actually her plan is to sneak away and celebrate with soldiers about to be sent overseas. She convinces Norval to cover for her and to loan her his car. Trudy is gone all night. Drunk, pregnant, and now married to an elusive Ignatz Ratzkiwatzki, she drives up to find Norval sleeping curled up in the foyer of the movie house. In the two scenes around the Morgan’s Creek Regent theatre, Sturges wedges in some barely noticeable jabs and in-jokes.

Start with what’s playing. Four posters are in the foyer around the box office. One is sitting on an easel turned largely away from us. The other three are mostly blocked by actors, partially framed, or thrown out of focus. But by freezing the film we can make out the titles of these three fakes.

The most visible film is Chaos over Taos, clearly a Paramount release.

You can also make out The Private and the Public, which also bears the Paramount logo. Its poster is behind Norval. Much harder to discern is the title of the third feature on the program, Maggie of the Marines. It’s barely visible for a few frames, glimpsed over Trudy’s right shoulder.

Knowing Sturges’ penchant for playfulness, we can see two of these as parodies of Paramount releases. The Private and the Public seems clearly a reference to The Major and the Minor, directed by Billy Wilder and released in early fall of 1942. Sturges began shooting Morgan’s Creek in October of that year and finished in early 1943, so he would have been well aware of the Wilder film. As an extra fillip, the star of The Private and the Public is listed as Fred McMany, a reference to Paramount star Fred MacMurray.

Then there’s Chaos over Taos. The title is weird enough, relying on an eye-rhyme and being so tough to pronounce that no studio would ever choose it. The star names, Armando Torez and Maria Robles, don’t suggest any Paramount contract players to me, but this was the period when Hispanic and Latino stars began to headline Hollywood movies: Carmen Miranda, Lupé Velez, and Cesar Romero are the most famous. Emphasizing Latin American plots, players, and locations was part of Hollywood’s contribution to Roosevelt’s Good Neighbor policy. The effort was seen most famously in Disney’s wonderful Saludos Amigos cartoon (1942) but also in a series of Fox musicals with cities named in the titles (Down Argentine Way, That Night in Rio, Week-end in Havana). Chaos over Taos could be Sturges’ dig at a then-current trend in political correctness and at another studio’s production cycle. As for the genre, Chaos/Taos is a flyboy movie and Paramount made several of those—three B-films in 1941 alone (Flying Blind, Forced Landing, and Power Dive, all featuring Richard Arlen).

What then of Maggie of the Marines? It’s likely that Sturges grabbed the title from an October 1942 news story about a dog that wandered into a marine camp in the Panama Canal. Details are at the bottom of today’s entry. We can imagine the sort of heart-warming comedy it might have been, as long as Sturges wasn’t at the helm.

Etc., etc., and etc.

Finally, there’s a matter of exhibition. Just as in Sullivan, the theatre in The Miracle of Morgan’s Creek proclaims a very long show: “3 Big Features Tonight, Short Subjects, Newsreel, and Boxo” (another mockery of Screeno). Norval tells Trudy that the whole shebang is scheduled to end at about 1:10.

Unlike the bill of fare in Sullivan’s Travels, the long show at Morgan’s Creek motivates plot action. Trudy uses the pretext of a long triple feature to get her father’s permission to stay out late. But it may not be too much to see in Sturges’ interest in triple features another contemporary reference.

Triple features emerged in the mid-1930s, partly because of high output from the studios and partly because of competition among exhibitors. Dan Goldberg wrote in Variety in 1938:

In a wild scramble for immediate returns without any thought to the outcome, the exhibitors have tried freaks and stunts rather than policy and operation. There have been double features, triple features, bank nite, screeno, keeno, bingo, and giveaways of all kinds, including dishes, flatware, linenware, framed pictures, wall plaques, etc., etc., and etc. There are many houses around here [Chicago] which are getting a 15c and 20c admission and giving away merchandise valued at 11c and more.

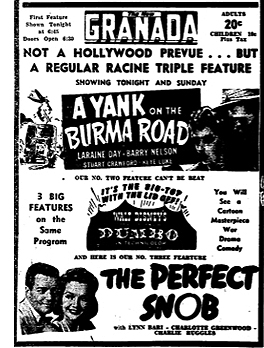

The studios hated double-feature programs but the public, voting its wallet, preferred them. Duals, as they were called, were largely a subsequent-run phenomenon, but because of the vast number of releases and block booking, they crept into first-run venues too. Triple bills were far less common and typically included two or even three B pictures. Most A-grade pictures aimed to come in under 100 minutes, and a B was typically sixty to seventy minutes long, so a triple feature of an A and two Bs wouldn’t be stupendously long. In the Racine triple feature on the right, two Bs flank Dumbo, a 62-minute movie, and the whole program, without shorts, trailers, and intermissions, would last only a little over three hours. Many triple bills seem to have consisted of three Bs. Sometimes the movies weren’t all features: a cartoon or a serial episode might be counted as one of the “Three Big Hits” advertised.

The studios hated double-feature programs but the public, voting its wallet, preferred them. Duals, as they were called, were largely a subsequent-run phenomenon, but because of the vast number of releases and block booking, they crept into first-run venues too. Triple bills were far less common and typically included two or even three B pictures. Most A-grade pictures aimed to come in under 100 minutes, and a B was typically sixty to seventy minutes long, so a triple feature of an A and two Bs wouldn’t be stupendously long. In the Racine triple feature on the right, two Bs flank Dumbo, a 62-minute movie, and the whole program, without shorts, trailers, and intermissions, would last only a little over three hours. Many triple bills seem to have consisted of three Bs. Sometimes the movies weren’t all features: a cartoon or a serial episode might be counted as one of the “Three Big Hits” advertised.

Triples were evidently less popular with audiences than duals. Perhaps people weren’t willing to spare such a big block of time, or they suspected that the lesser items on the bill weren’t worth watching. Jeff Smith suggests to me that adding a B to an A looks like a bonus, but two or three Bs look like a dumping ground. Interestingly, when Trudy tells Norval she plans to skip out on him, he protests: “I won’t do it! I won’t sit through three features all by myself.” Trudy asks plaintively: “Couldn’t you sleep through a couple of ’em?”

While Sturges was preparing Morgan’s Creek, he might well have noticed some Variety stories tracing a controversy about triple bills in the Midwest. A chain in St. Louis had shifted to this policy, and to retaliate a rival chain began four-hour shows consisting of two features and sixty minutes of shorts. In late 1940, a civic group, the Better Films Council of Greater St. Louis, put pressure on exhibitors to oppose long programs. The Council claimed that such bills were “a physical and mental strain on children and young people,” and that family-appropriate films were sometimes accompanied by “adult” ones. Getting no cooperation from the theatre circuits, the Better Film Council announced in early 1941 that it was going to introduce state legislation to ban triple features. This effort evidently came to nothing.

As if in response to bluenose worries about long programs, Sturges gives the lucky Morgan’s Creek patrons a movie banquet that ends in the wee hours. And ironically, Trudy would have suffered less “physical and mental strain” in the days and weeks thereafter if she’d gone to the movies and not kissed the boys goodbye. The Regent’s absurdly inflated program may be Sturges’ dig at both a contemporary trend and those who fretted about it.

Watching me rake these apparently innocuous frames, you may be asking: Is David going all Room-237 on us? Actually, I see today’s entry as in the spirit of an earlier one, which also has an enigmatic Sturges connection. I’m interested in the moments when Hollywood is talking to itself.

We tend to think that the studios made movies to communicate with the public, and that’s surely true. But we tend to forget that filmmakers were sometimes talking to each other. In the Zanuck-produced Hollywood Cavalcade (1939), a romance of silent-era moviemaking, director Don Ameche turns down Rin-Tin-Tin for a project. The obvious joke is that the pooch became a big star, but how many viewers would appreciate the in-joke that Zanuck launched his career at Warners writing scripts for Rinty? Did the public know that Slim and Steve, the nicknames swapped between Bogart and Bacall in To Have and Have Not, were the ones used by Hawks and his wife? Would ordinary moviegoers catch the reference to Archie Leach in His Girl Friday or notice Jed Leland’s column in the newspaper in The Magnificent Ambersons?

Some would have. Moviegoers of the day were better-educated than the populace in general, and the biggest fans went several times every week. But even if the audience missed these bits, the filmmakers’ peers might not. These movies were made by youngish people who liked to have fun–sometimes at each other’s expense—and nothing is more fun than very esoteric in-jokes.

The problem is that these other examples are highlighted in dialogue, but some of Miracle‘s in-jokes are almost completely buried. They’re more akin to the current vogue for Easter Eggs in sets and props. Unlike the recent instances, though, Sturges’s hints are hard to catch during projection, and he couldn’t have counted on viewers mulling over them frame by frame, as our directors can.

Perhaps he intended to show those posters more fully but had to forego that option during filming or cutting. Or perhaps he included them just for his own amusement–that is, not for the general public, nor even for his peers, but merely for the pleasure of putting in things that only he and his team knew about. If that seems implausible, let me ask: If you could do it, wouldn’t you?

The fourth poster, after some fiddling with the Skew and Perspective tools in PhotoShop, reveals itself as another aerial adventure: Eagle something…. Eagle Blood, maybe? For an example of a drama using real film titles in its movie marquees, see this entry.

On duals and triples, see “Triple Features Seen as Nabes’ Salvation,” Variety (22 January 1935), 3; Dan Goldberg, “Chicago Merry-Go-Round,” Variety 24 October 1938, p. 21; “Now It’s Duals, with Vaudeville, At the Loop Oriental,” Variety (25 January 1939), 5; “Single-Billing Idea Up Again But Practically It’s Still NSG,” Variety (26 August 1942), 13. On the St. Louis controversy, see “Better Film Council Queries St. L. Exhibs on Duals and Triples” Variety (23 October 1940), 21, and “St. Louis Group Seeks to Outlaw Triple Features,” Variety (26 February 1941), 21.

The embedded ad for a triple feature comes from The Racine Journal-Times (11 July 1942), 8.

No need to write me about the most obvious in-joke in Morgan’s Creek: the fact that it incorporates two major characters from The Great McGinty (1940) and doesn’t even bother to credit the actors. Cheeky, this Sturges fellow.

From The Daily Gazette (Berkeley , California, 19 October 1942).