Archive for the 'Film genres' Category

How the world ended in 1916

The End of the World (1916).

DB here:

The pull-quote might be “Gripping entertainment and a vivid introduction to storytelling strategies characteristic of Danish silent cinema!” (Too long for a poster, though.) It appears in my essay on a remarkable silent film you may not know. I bet you’d like it.

Danish cinema has gripped my interest for about fifty years. Like most cinéphiles, I started with Dreyer, moved on to Christensen, and then just tried to keep up with trends leading to Scherfig, Vinterberg, Winding Refn, Anders Thomas Jensen, and Dogme. There always seemed to be a new comedy or noir or psychological drama or just weird-ass experiment to keep my loyalty (most recently, the well-crafted Another Round).

One of our first blog entries, on 20 October 2006, was devoted to an anthology on the great film company Nordisk. Soon I was chattering about von Trier’s editing in The Boss of It All and surveying a big batch of recent releases.

Now this national cinema’s silent-era history is coming steadily online. The Danes are too modest to brag about the enormous accomplishment of making so many beautifully restored classics available for anyone to watch. But here they are, accompanied by thematic essays from critics and historians.

Like other Little Cinemas That Could (Hong Kong, Taiwan. Iran), Denmark attracts me because it has shown what can be done a lot of imagination on smallish budgets. Or sometimes, biggish budgets. That’s an impulse that emerged in the 1910s when Nordisk was struggling to keep a foothold in the international market during the Great War. One result was a pair of remarkable spectacles.

A Trip to Mars (Himmelskibet, 1918) is a massive, nutty plea for peace and international—make that interplanetary—understanding. The Martians are more or less like us, except they don’t kill other creatures, which leaves them time to assemble in carefully picturesque crowds and invest in ambitious infrastructure projects.

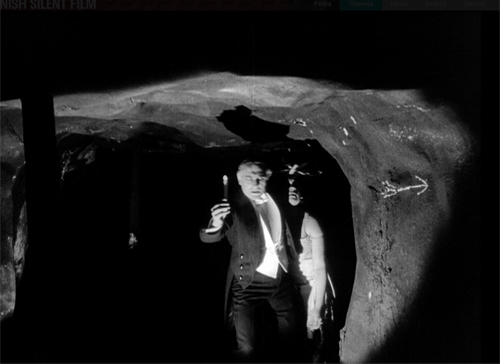

The other big Nordisk production was The End of the World (Verdens Undergang, 1916). A comet is plunging toward earth. Can we avoid collision? Or at least survive?

All the conventions of the cosmic disaster movie (Armageddon, Independence Day, 2012) are already in place. We have the innocent family, the corrupt capitalist squeezing money out of catastrophe, the scientists trying to calm the public, and of course the separated lovers who must find one another in the midst of chaos.

The special effects range from passable to truly impressive, as in the model of the village under fiery bombardment, surmounting today’s entry. The comet’s approach is cleverly suggested as a blip in the sky, and the shots of the heroine’s drowned neighborhood are splendid.

Just as remarkable are other technical achievements. The lighting in the underground passages of the capitalist’s mansion, with its Caligariesque steps, could teach the Germans a few tricks, and the miners’ fierce assault on the plutocrats is cut with rowdy, immersive vigor.

August Blom had made his reputation with Asta Nielsen dramas and another would-be blockbuster (Atlantis, 1913). He’s often considered a stolid director, but The End of the World seems to me an underrated achievement. Dismissed by many critics as over-produced, its ambitious spectacle is probably more to our current taste for overwhelming scale. For us, it seems, too much is never enough.

So I recommend to your attention this remarkable movie. As usual, I throw in a case for the 1910s as one of the great and glorious eras of film history. You can handily sample further evidence in the film links alongside the essay.

Thanks to Thomas Christensen and his colleagues at the Danish Film Archive. It was fun!

There’s always more to say about the Danes. Outside our blog entries, I’ve written about Nordisk and the “tableau aesthetic” and on early Dreyer in another essay on the Danish Film Institute site.

The End of the World (1916).

Merrily he rolls along: A belated birthday tribute to Stephen Sondheim

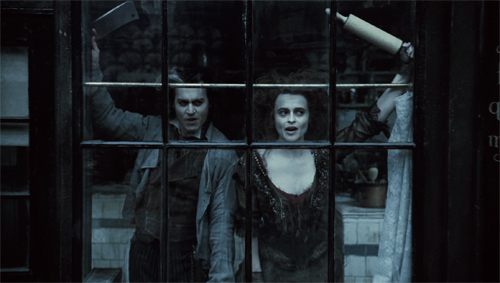

Sweeney Todd: The Demon Barber of Fleet Street (Tim Burton, 2007).

DB here:

Last month Stephen Sondheim celebrated his ninety-first birthday. By coincidence, I just finished a section on him in my current book on popular storytelling.

The argument there is that art at all levels, high and low, mass and elite, depends on novelty. That demanded accelerated in the twentieth century, with the explosion of book publishing, magazines, film, radio, theatre, and television. I see this process as a vast energy of crossover. Popular and “middlebrow” storytelling picked up on avant-garde innovations. But it seems to me that modernism, even the High Modernism of Joyce, Woolf, and Faulkner borrow more than is usually noted from conventions of popular storytelling. I hazard the view that it’s enlightening to look at how experimentation, innovations that open new avenues of artistic expression, emerge in mass-audience art.

Nowadays, most intellectuals have found something to love in mass culture. (“We are all nerds now.”) It wasn’t always so. In England and America, the “battle of the brows” had as one consequence the idea that true art, usually typified by High Modernism or the more radical avant-garde, was being squeezed. On one side was mass culture, manufactured as a commodity designed to sooth the masses. On the other was “middlebrow” art, which mimicked the techniques of modernism but made them simple enough for suburbanites to follow. By the 1960s, the people who believed in this trinity were in the minority, partly because they began to realize that centering on the most difficult side of modernism created too austere a prototype of all ambitious art. Irving Howe called this “The Decline of the New.”

Not that everything is a mashup. But I think now we all realize that crossover is a valid expressive option, probably the most pervasive one. The mass media make room for a huge amount of creativity that can’t simply be dismissed as lowbrow or middlebrow. And one reason it can’t is because we can still be excited by unexpected innovations.

Hence the importance of the nearly seventy-year career of a man who confessed a “taste for experiment in the commercial theatre.”

Experiments that are fun

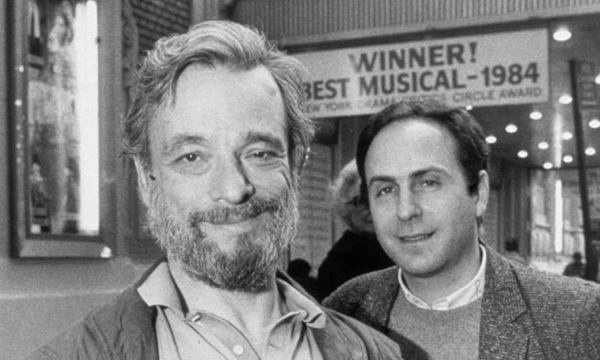

Stephen Sondheim and Leonard Bernstein.

You couldn’t, I think, find a better case for the prospects for experiment in popular culture than his work. His fondness for stage games is part of a theatre tradition we might call “light modernism,” a merging of avant-garde strategies with traditions of popular entertainment. It stretches back to Cocteau’s Parade (1917) and includes the work of Pirandello. Similarly, a trend in British theatre fused aspects of modern theatre (Pinter, Beckett, Ionesco) with the comedy of P. G. Wodehouse and The Goon Show. Tom Stoppard’s Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead (1966) showed that what was “offstage” in one story could constitute the amusingly doom-laden plot of another.

Alan Ayckbourn dedicated his career to formal experimentation with space (three bedrooms as one in Bedroom Farce, 1975) and time (simultaneous action in How the Other Half Loves, 1969). Intimate Exchanges (1983) spreads forking-path plots across eight separate plays and sixteen possible endings. (Two of the variants are on display in Resnais’ films Smoking/ No Smoking of 1993.) House and Garden (1999) consists of two plays performed simultaneously in two auditoriums, with actors dashing between them. Ayckbourn’s most famous cycle, The Norman Conquests (1973) displays a “stacked” structure; each play gathers all the action taking place in one location and skips over scenes elsewhere, which are assembled in the other plays. The audience must construct the overall story, remembering what has happened just before the scene we see now.

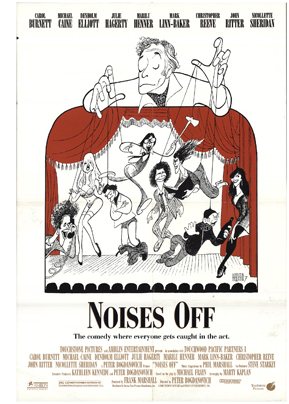

Michael Frayn’s virtuoso Noises Off (1982) probably owes something to Stoppard and Ayckbourn, but it offers its own switcheroo. The opening scene of a sex farce is rehearsed in our first act, is performed skillfully in our second, and collapses in our third view. Crucially, the smooth show of the second act is presented to us in a backstage view displaying the intricate timing involved. Again, an abstract formal concept is mapped onto a conventional scenario, the comedy of a bungled stage production.

Michael Frayn’s virtuoso Noises Off (1982) probably owes something to Stoppard and Ayckbourn, but it offers its own switcheroo. The opening scene of a sex farce is rehearsed in our first act, is performed skillfully in our second, and collapses in our third view. Crucially, the smooth show of the second act is presented to us in a backstage view displaying the intricate timing involved. Again, an abstract formal concept is mapped onto a conventional scenario, the comedy of a bungled stage production.

Mystery plots make useful targets for this sort of popular experiment. Ayckbourn plotted some plays as quasi-thrillers, and Stoppard’s The Real Inspector Hound (1968) is a parody of the country-house murder. Stoppard undercuts the mystery by a Pirandellian device: two critics down in front are commenting as the performance unfolds. This gives Stoppard a chance to mock pretentious reviewing language. The standard whodunit device of reenacting the murder transforms into a replay of the opening act, but now with the critics taking the roles of detective and victim.

Also not surprisingly, both Ayckbourn and Stoppard declared themselves influenced by cinema, a reliable marker of crossover in modern media. Ayckbourn plays were adapted, with ingratiating wit, to film, while Stoppard wrote several scripts, most famously Shakespeare in Love (1998), which if the term means anything must count as defiantly middlebrow entertainment.

Sondheim is on the same frequency as these masters, but has, I think, greater bandwidth. He plunged into cinephilia more deeply. His early musical influences were Hollywood scores, notably that for Hangover Square (1945); Sweeney Todd, The Demon Barber of Fleet Street (1979) was his tribute to Bernard Herrmann. A Little Night Music (1973) and Passion (1994) were adapted from films. Many of his songs refer to movies, and he composed music for Stavisky (1974), Dick Tracy (1990), and other projects. He was even a clapper boy for John Huston on Beat the Devil (1953).

Instead of parodying mysteries, he has been deeply committed to them. Detective fiction is his favorite reading, and as a puzzle addict he has spent hours devising murder games. “I have always taken murder mysteries rather seriously.” Both Company (1970) and Follies (1971) were initially planned as mysteries, with the latter concerned not with “whodunit?” but “who’ll do it?” Sweeney Todd is a paradigmatic revenge thriller. Asked by Herbert Ross to write a film, Sondheim and Anthony Perkins (another admirer of “the trick kind” of mystery practiced by John Dickson Carr) came up with The Last of Sheila (1973).With George Furth, Sondheim wrote a play, Getting Away with Murder (1996), and with Perkins he planned the unproduced Chorus Girl Murder Case, an homage to 1940s Bob Hope movies. The clues would be hidden in the songs.

Fiddling with formula

Sondheim and producer/director Hal Prince (left) during rehearsals for Merrily We Roll Along.

Sondheim’s zest for film and mystery fiction reflects a deep admiration for popular culture. It’s one thing to enjoy it, as Ayckbourn and Stoppard clearly do, while also poking fun at its silly side. It’s something else to appreciate its artistry in depth and try to master the conventions yourself. Despite learning “tautness” from the austere avant-gardist Milton Babbitt, Sondheim took as his mentor Oscar Hammerstein II. Tin Pan Alley, with its finger-snap rhythms and suave wordplay, pushed him toward a brisk cleverness. The virtuoso rhymes in his bouncy “Comedy Tonight” (A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum, 1962) inevitably bring a grin: Panderers! Philanderers! Cupidity! Timidity! . . . Tumblers, grumblers, bumblers, fumblers!

While executing these pirouettes, the song provides a Cliffs Notes guide to Roman New Comedy by contrasting it with tragedy. Tonight, weighty affairs will just have to wait. Sondheim similarly lays bare a convention in his script for the unproduced movie Singing Out Loud, where the couple gradually learn that it’s okay to express emotion in song. “They have to learn to overcome the unreality of it and break into song in the conventional manner of all musicals.”

By taking fun seriously, Sondheim ransacks culture high and low for occasions for experimentation. He was crucially influenced by Allegro (1947), an ambitious Rodgers and Hammerstein musical he considered “startlingly experimental in form and style.” Its use of sliding screens to create “cinematic staging” would become standard in later musicals. He calls Hammerstein “the great experimenter” who used the verse sections of songs to explore possibilities of structure, melody, and harmony.

Sondhim’s breakthrough experiment was Company (1970). It consists of flashbacks framed by the protagonist Robert’s thirty-fifth birthday party. Sondheim claimed it offered “a story without a plot.” The flashbacks don’t supply a goal-directed character arc and instead sample Robert’s bachelor lifestyle and its effects on his three girlfriends and the five married couples in his circle. The result is a compare-and-contrast pattern of parallels. Complicating things further, bits of action are accompanied by a chorus-like commentary from characters not in the scene. Still, there is a certain progression to the whole, indicated by Robert’s disillusioned but faintly hopeful final song, “Being Alive.”

The nonlinearity of Company poimts up Sondheim’s impulse to play with time, viewpoint, and other techniques. Assassins (1990) moves freely back and forth across a hundred years. In Follies characters argue with their former selves. Sunday in the Park with George (1984), built on parallels between two painters, assigns inner monologues to artist and model; characteristically, Sondheim expresses jumbled thoughts by avoiding rhymes. Another duplex structure (Before/ After) shapes Into the Woods (1987), s a virtuoso braiding of classic folktales into a single plot.

Several plays utilize a narrator, who may take a role or converse with the characters. The Narrator of Into the Woods is killed fairly early in the action. Alternatively, Sondheim conceived Passion as an epistolary musical. Characters writing or reading letters operate “somewhere between aria and recitative,” rendering the emotional climaxes as “read rather than acted.” In this excerpt, Giorgio goes to bed with Clara while Fosca is reading his letter breaking up with her. This is a concert performance; in a full production the couple undress on one side of the stage, while Fosca reads the letter. Time floats uncertainly

Working in musical theatre gave Sondheim a layer of implication beyond what Stoppard and Ayckbourn had available with spoken dialogue. A score can evoke earlier scenes through leitmotifs and can enhance characterization. Starting with Anyone Can Whistle (1964) Sondheim created pastiche songs that vary from the show’s overall style. Merrily We Roll Along incorporates cabaret acts (“Bobby and Jackie and Jack”) while Assassins integrates various popular musical traditions, from vaudeville to melodrama. We might think of these pastiches as akin to the “polystylism” of the chapters of Ulysses, which Sondheim strongly admires.

Pacific Overtures (1976), a chronicle of Japan’s early engagements with the west, has the structure of a “portmanteau” film composed of exemplary episodes. It too has a narrator, the Reciter, and its experiments include turning renga linked verse into a passed-along song. The most formally daring scene, “Someone in a Tree,” stages the March 1854 signing of the treaty opening up ports to American ships. We do not see the ceremony, which is held in a secure house.

The Reciter questions an old man who claims that as a boy he watched the negotiations from a tree. During their dialogue, a boy clambers up the tree, and he and his older self collaborate in reporting the event he sees but cannot hear. Then the Reciter discovers a samurai guard hiding beneath the floorboards. He reports what he hears but cannot see. (Beware the YouTube ad at the start.)

As the singers’ accounts intertwine, a moment is assembled through partial perceptions. In a gesture reminiscent of Joseph Conrad’s novels, the event is broken up, made accessible only through partial viewpoints. And only the witnesses attest to the event; without them, we have no access to history. “I’m a fragment of the day./ If I weren’t, who’s to say/ Things would happen here the way/ That they’re happening?” In adapting novelistic techniques for relativistic point of view to the stage, Sondheim, as an experimental storyteller, is ready to plunder any tradition that can yield something fresh.

Form, “content,” and everything in between

Sondheim and collaborator James Lapine.

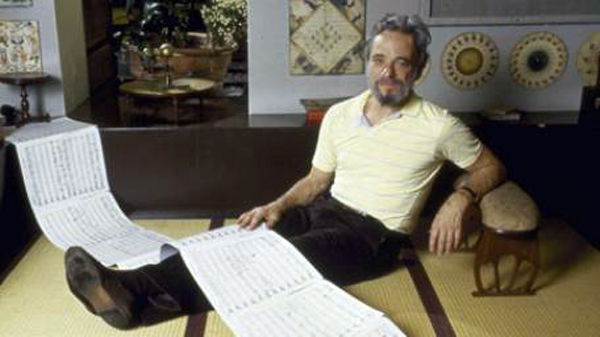

In his invaluable creative memoirs, Finishing the Hat (2010) and Look, I Made a Hat (2011), Sondheim claims as a basic creative principle “Content dictates form.” But his puzzle-addict efforts to seek out difficulties to be overcome makes me think that this is more alibi than axiom.

I’d rather think that like many experimental artists, Sondheim uses “content” (whatever that is: subject matter, theme, bare-bones story) as at best one ingredient and often as a handy excuse. Sometimes audiences need help when faced with radical novelty. People may have been more receptive to Debussy’s daring pieces because of the “atmospheric” connotations of their titles. The stratagem of labeling one movement of “La Mer” as “From Dawn to Noon on the Sea” was pointed out by Erik Satie: “I liked the part at quarter to eleven best.”

Granted that Sondheim tries to suit his words and music to the genre and story he has selected, he often seems to take “content” as a pretext for solving problems he sets himself. Who else would decide to write all the songs for A Little Night Music in waltz tempo, not least for the challenge of avoiding monotony?

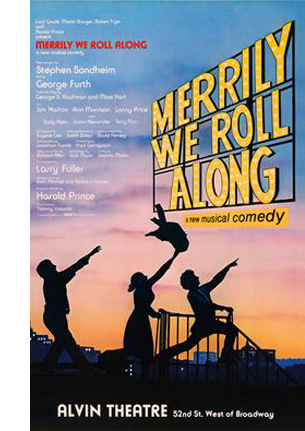

I think Merrily We Roll Along is a good example of how, accepting an initial problem, Sondheim complicates matters “unnecessarily.” This largely forgotten 1934 Kaufman and Hart comedy was formally daring: its scenes play out in reverse chronology, so the last scenes we see in the plot are the first events of the story. In adapting the play to a musical, Sondheim created a story of three twentysomethings trying to break into show business.

I think Merrily We Roll Along is a good example of how, accepting an initial problem, Sondheim complicates matters “unnecessarily.” This largely forgotten 1934 Kaufman and Hart comedy was formally daring: its scenes play out in reverse chronology, so the last scenes we see in the plot are the first events of the story. In adapting the play to a musical, Sondheim created a story of three twentysomethings trying to break into show business.

The purported rationale for telling their story backward is that it poignantly traces the loss of youthful idealism. But that arc could be just as poignant laid out in chronological order–or, if you want advance knowledge of how the struggles will turn out, via chronological flashbacks wrapped in a contemporary time frame. The reverse chronology seems both an experiment in whether audiences can follow the string of events and an effort to end a sad story in an upbeat way, with the characters still vigorous and hopeful–while we know what awaits them.

Sondheim faced an initial task of making the time scheme clear. He came up with transitional choral passages by the whole company that signal the shift to an earlier block of time. Different productions experimented with ways of reinforcing these musical tags, such as a synoptic slide show reminiscent of the “News on the March” sequence of Citizen Kane.

But the inverted chronology of Merrily We Roll Along also justifies experiments in musical texture. Because the play is about friendship, melodic motifs are swapped among the characters in their soliloquy songs. Moreover, in a 1-2-3 plot, Sondheim explains in Finishing the Hat, fully vocalized melodies are given reprises, shorter versions of the original number. Sondheim could have followed this convention. Instead, in relentless adherence to the reverse chronology, he made the reprises come first, as appetizers for songs yet to be fully heard. The puzzle addict will try to fit everything together in surprising ways, whether the audience realizes the fine points or not.

Solving one problem can launch a cascade of further problems. To introduce a 1980s audience to the musical ambience of Broadway’s heyday, Sondheim opted to revive the thirty-two bar song that he and his generation had “stretched out of recognition.” But then his penchant for pastiche posed a new problem. How to use that schmaltzy song form not just to satirize superficial characters like Joe the producer but to sustain connection to the sympathetic characters when they express authentic emotion?

Sometimes the problem is set not by “content” but by genre, tradition, or purely practical contingencies. Sondheim embraces show-biz conventions to discover what he can do with them. Hammerstein told him that the opening number can make or break a show, so Sondheim strives for a grabber when he can. The eleven o’clock number, a hangover from the days when shows began at eight-thirty, demands a show-stopping vehicle for the stars–e.g. “Anything You Can Do” in Annie, Get Your Gun. For Anyone Can Whistle, Sondheim wrote “There’s Always a Woman,” a rapid-fire comic confrontation between the two stars Angela Lansbury and Lee Remick, dressed identically. He conceived it as “the eleven o’clock number to end all eleven o’clock numbers.” It didn’t achieve what he wanted (“more like a ten-fifteen”) but it indicates his inclination to display virtuosity in response to purely formal demands.

Look, he made a show

Finishing the Hat and Look, I Made a Hat take us into the artisan’s kitchen–not only the studio or the stage where a team comes together but also the kitchen that’s the mind of the creator, who sweats out as much as possible beforehand. Sondheim shares with us the “choices, decisions and mistakes in every attempt to make something that wasn’t there before.”

This is a rarer accomplishment than you might think. Relatively few artists in any medium have the wish or ability to probe their creative process in detail, from conception to minutiae of execution. There are plenty of artists who talk of story sources and bursts of inspiration, but they seldom get down to the compromises, workarounds, and failed efforts. The best such books on popular storytelling, Sidney Lumet’s Making Movies and Patricia Highsmith’s Plotting and Writing Suspense Fiction, are illuminating, but nothing compared to the multilayered self-consciousness Sondheim brings to the task. He notes: “The explication of any craft, when articulated by an experienced practitioner, can be not only intriguing but also valuable.”

It helps when the artist works in brief, segmented forms, such as the songs that make up a musical. They can be analyzed line by line, and can illustrate the challenges of word choice, rhythm, and rhyme as they relate to the ongoing story, the portrayal of character, and of course the score. This engineering side of construction, basic to popular art, is attractive to a practitioner who happens to be a puzzle fiend. He makes every choice a challenge to his ingenuity.

Take one example, “A Little Priest” from Sweeney Todd. Sweeney has decided to turn his lust for personal vengeance into random barber-chair homicide. This scheme suits Mrs. Lovett’s need to produce better meat pies. The result is a list song, a Sondheim favorite. Here’s the rendition of the Broadway original with Len Cariou and Angela Lansbury, for most of us the definitive version.

The couple deliriously catalogue what citizens might furnish appropriate ingredients. Sondheim’s founding choice: the list will consist not of individuals, who would need naming, but of social types whose titles can rhyme more easily. Sweeney role-plays a customer checking Mrs. Lovett’s imaginary wares.

Todd: What is that?

Mrs. Lovett: It’s priest./ Have a little priest.

Todd: Is it really good?

Mrs, Lovett: Sir, it’s too good, at least./ Then again, they don’t commit sins of the flesh./ So it’s pretty fresh.

Todd: Awful lot of fat.

Mrs. Lovett: Only where it sat.

Todd: Haven’t you got poet/ Or something like that?

Mrs. Lovett: No, you see the trouble with poet/ Is how do you know it’s/ Deceased?/ Try the priest.

Second choice: the song must be constructed so that the rhyming emphasis falls on the types, so the lines end on the name of the profession, as above. Third choice, new constraint: Throughout the play, Sondheim tries for triple rhymes, so one- or two-syllable professions (priest, poet) will allow for that. Fourth choice: the need to build the song out of short lines, which will permit “an increasingly intricate rhyme scheme.” That’s on display here, with priest–least–deceased–priest threaded with flesh–fresh and fat–sat–that and poet–know it.

The song surveys a range of social types, while reminding us of Sweeney’s main target Judge Turpin (“I’ll come again/ When you have judge on the menu”). The climax of the song declares a perverse commitment to equity. “We’ll not discriminate great from small/ No, we’ll serve anyone/ Meaning anyone–/ And to anyone/ At all.” The catalogue culminates in a sprightly celebration of mass murder.

Finicky as ever, Sondheim confesses that he never liked the line “Meaning anyone,” which is a place-filler, but now he says he knows how to improve it.

Why probe the artist’s craft in such detail? Sondheim notes that journalistic reviewers aren’t trained in technique or don’t know the trade secrets; they’re just declaring what they like or dislike. More intellectual and academic critics are inclined to write broad overviews, usually about the cultural sources and effects of the music. A practitioner who explains the cascade of decisions, freely made or imposed from without, can provide something rare. Just as the sports fan enjoys learning the fine points, learning the tricks of the artist’s trade can boost our appreciation. We can learn to enjoy “the spectacle of skill.”

No surprise: I was reminded of the historical poetics of cinema. This approach to film studies tries to analyze how filmmakers draw on the menus of options normalized in particular times and places. In trying to discover principles of craft practice, we seek out any information we can glean from artisans. For this purpose, we’ll not discriminate great from small.

At the movies

Sondheim with Steven Spielberg on the set of the remake of West Side Story.

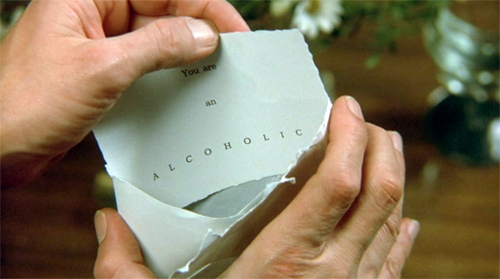

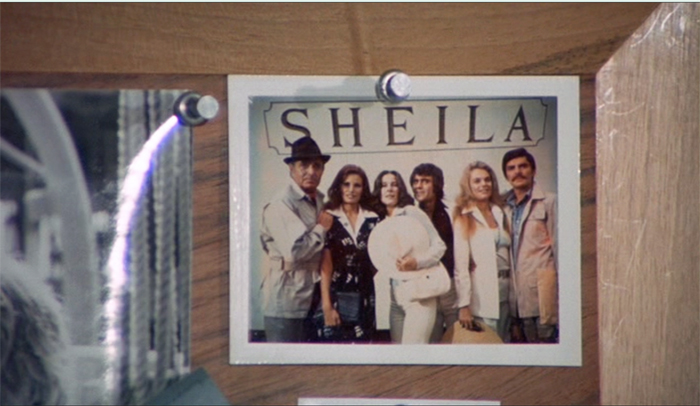

The Last of Sheila is a brittle, cynical satire on the film industry while being a well-designed classic mystery. Sheila Greene is struck down by a hit-and-run driver after she storms out of a party she and her husband Clinton have been holding. Under the promise of a potential movie deal, Clinton gathers six suspects on a pleasure cruise on the French Riviera. Once they’re are aboard, Clinton announces the entertainment: a mystery game. Each guest receives a card declaring a secret, such as “You are a homosexual” and “You are an alcoholic.” Clinton assures them that each is simply “a pretend piece of gossip,” but it becomes clear that the game is designed to expose someone, not necessarily the recipient, as guilty of the card’s charge. Meanwhile, Clinton tries to discover Sheila’s killer.

Every night, at the port they visit, the guests must follow clues to link one of them to a past transgression. The game is interrupted when one of the travelers is killed, and so the survivors embark on their own investigation. As in an Agatha Christie novel, the characters are stock types. There’s the vapid star, her hanger-on husband, the over-the-hill director, the rapacious talent agent, the second-tier screenwriter, and his heiress wife. Again, as in Christie novels like Death on the Nile and Murder on the Orient Express, the yacht cruise isolates the suspects and allows them to debate the identity of the culprit but also also to reveal Clinton’s scheme. In response, the killer has conceived a counterplot for baffling the other guests. Instead of these Christie novels, there is no designated Great Detective to take Hercule Poirot’s place. Any of the people hazarding solutions could be guilty.

In the spirit of the “fair play” detective novel, the audience is provided some clues that flit by, but can be checked on a replay. It’s not a spoiler to note the casual early appearance of an icepick, or the glimpses of some–but not all–of the clue cards.

By contrast, as John Dickson Carr points out, the really skillful mystery writer rubs your nose in the clues. It’s not a matter of a passing mention of the color of a man’s tie, or the way a character pronounced a word.

The masterpiece of detection is not constructed from “a” clue, or “a” circumstance. . . . It is not at all necessary to mislead the reader. Merely state your evidence, and the reader will mislead himself. Therefore, the craftsman will do more than mention his clues: he will stress them, dangle them like a watch in front of a baby, and turn them over lovingly in his hands.

The best example of this tactic in the film is the photograph at the bottom of this entry. The shot lets us dwell on Clinton’s apparently innocuous photo of his guests. Elsewhere the script plays up that old favorite, the discarded cigarette butt.

Sondheim and Perkins’ passion for classic detection is revealed in a long sequence of pure ratiocination. Across twenty-one minutes in the yacht’s lounge, one guest reconstructs the scenario behind Clinton’s game. The layout of space, in both long shots and shot/reverse shot, is quite precise and varied. Of course there are clues in the behavior of certain characters.

Part of the reconstruction turns out to be erroneous, as in the detective-novel convention positing an initial, faulty solution. In all, The Last of Sheila, while memorializing the sort of scavenger hunts and elaborate games Sondheim put his friends through, remains a rare example of an updating of the classic whodunit.

By contrast, the film adaptation of Sweeney Todd is a suspense thriller. The plot doesn’t hinge on an investigation but a pursuit (although that does yield a surprise revelation). Sondheim considers it the only satisfactory film version of one of his shows. “This is not the movie of a stage show. This is a movie based on a stage show.” But then what was the show? Opera? Operetta? No. “What Sweeney Todd really is is a movie for the stage.”

And a grim, brutal one at that. Tim Burton has developed Sondheim’s original through several cinematic strategies. One emphasizes Sweeney’s willed estrangement from humanity. If the stage Sweeney, often played by a large man, has a certain sweeping bravado, Sweeney on film scowls in soft-spoken fury. His puckered brows and pinched lips are set in a face as unearthly pale as a cadaver’s, or a clown’s. This seething little man is presented as virtually locked in his quarters, peering out at the world on which he will wreak vengeance.

Sweeney’s isolation is given a narcissistic cast when he unpacks his razors. He who has no human ties croons to “my faithful friends.”

Mrs. Lovett looks on, trying to secure a connection: “I’m your friend, too.” But he ignores her. Burton provides POV shots of Sweeney’s face reflected in his razor blade, a neat way of showing his self-absorption passing into violence.

At one point, he seems to register Mrs. Lovett’s gestures of affection, and Burton neatly shows the POV reflection shifting to her.

His contemplation of her as an ally can, it seems, only see her as another reflection of himself and an instrument of his vengeance–a tool, not a lover.

He rejects her affection (“Leave me”) and he twists the razor, turning the reflection back to him. He’s still locked in his solitary obsession.

He finishes the song alone, now even more committed to his mission. A final shot shows him gleefully peering out the window at the city he and his faithful friends will ravage.

Mrs. Lovett becomes his genuine accomplice in the song, “A Little Priest.” In the stage directions, Sondheim asks that Sweeney and Mrs. Lovett use pantomime to evoke the meat pies they want to harvest from Sweeney’s customers. In the film, however, the pies she has already made are surrogates for the ones she proposes.

Given the more tangible setting, Burton returns to the window motif; Mrs. Lovett’s shop becomes an extension of Sweeney’s enclosed world. The couple’s list-song takes place with the two of them at the windows, scanning the street for victims. As you’d expect, they spot a priest first.

If the barber shop upstairs is Sweeney’s mission control, the pie shop becomes his supply center. Mrs. Lovett realizes that she can get his friendship only by joining his plan for vengeance, and once he realizes her commitment, she becomes an attractive partner. They pledge their partnership in a rolling-pin waltz, and the sequence ends with a shot that echoes the earlier capstone, but including Mrs. Lovett.

There’s a lot more to be said about The Last of Sheila and Sweeney Todd, but I invoke them just to show that Sondheim’s talents can create robust, innovative, sometimes disturbing cinema.

I could imagine someone criticizing Sondheim as the ultimate middlebrow artist. Adapting foreign films (Smiles of a Summer Night, Scola’s Passion) and Grand Guignol to the American musical; turning Seurat’s Grande jatte into a living tableau (and naming the painter’s model Dot!); imposing games with time and viewpoint on a showgirls’ reunion; investing fairy-tale optimism with sinister implication–all can seem too clever by half. An objector might say that a Sondheim show doses schmaltz and hokum with just enough formal ingenuity to let audiences feel clever. But I think that sort of having-it-both-ways defines a great deal of popular entertainment, and it has its own value. Bergman and Seurat and Little Red Riding Hood remain unharmed by plays that take them as pretexts for ravishing music and cunning theatrical games. Formal ingenuity is not a small thing.

Sondheim opened new vistas for the musical to explore. I suppose you can call Lin-Manuel Miranda’s Hamilton middlebrow too, making rap and hip-hop safe for people who can afford a Broadway ticket. But if you think Miranda opened new paths, note that he thinks that Sondheim pointed the way. He took advice from Sondheim while writing the show, and he paid tribute in a preface to an interview:

He is musical theater’s greatest lyricist, full stop. The days of competition with other musical theater songwriters are done: We now talk about his work the way we talk about Shakespeare or Dickens or Picasso.

You don’t have to go that far to see that artists at all levels of taste innovate, and their efforts sometimes oblige us to see fresh expressive possibilities in their artforms. If we are all nerds now, we can become connoisseurs of the experimentation–sometimes subtle, sometimes bodacious–that pervades popular entertainment. Sondheim, meticulous and generous and tirelessly exploring, coaxes us to do that.

I’ve drawn most of my Sondheim quotations from Finishing the Hat: Collected Lyrics (1954-1981) with Attendant Comments, Principles, Heresies, Grudges, Whines and Anecdotes (Knopf, 2010) and Look, I Made a Hat: Collected Lyrics (1981-2011) with Attendant Comments, Amplifications, Dogmas, Harangues, Digressions, Anecdotes and Miscellany (Knopf, 2011). Other remarks come from Craig Zadan, Sondheim & Company (Harper & Row, 1994) and Meryl Secrest, Stephen Sondheim (Knopf, 1998). Google Book Search should help you locate my citations by phrase. Steve Swayne provides a thorough analysis of the role of cinema in his career in How Sondheim Found His Sound (University of Michigan Press, 2005), 159-213.

More general books about the craft traditions Sondheim adopts and revises are Philip Furia’s The Poets of Tin Pan Alley: A History of America’s Great Lyricists (Oxford, 1992) and Jack Viertel, The Secret Life of the American Musical: How Broadway Shows Are Built (Farrar Straus Giroux, 2016. I’ve praised and applied Viertel’s account in this earlier entry.

Sondheim discusses the composition of “Someone in a Tree” in this interview with Frank Rich. The second part is especially revealing about Sondheim’s combining music and lyrics through a vamping figure. That accompaniment, detached from the sung melodies, depends on a “gradual change” principle that reminds me of the minimalist music of Glass (Einstein on the Beach, 1975) and Reich (Music for 18 Musicians, 1976) at the same period. A musicologist would probably correct me, but if the affinity holds good it would further show Sondheim’s pluralistic appropriation of many traditions. Thanks to Jeff Smith for discussions of this and for help with other musical matters.

The John Dickson Carr quotation comes from his 1946 essay, “The Grandest Game in the World.” The most complete version of it is in The Door to Doom and Other Detections, ed. Douglas G. Greene (Harper, 1980), 334-335.

Many fine appreciations of Sondheim appeared around his birthday, but I especially like this one by Jennie Singer, packed with clips.

For a long time Kristin and I have studied innovations in popular storytelling, as in her analysis of narrative in the New Hollywood, my book on the same area, her monograph on P. G. Wodehouse, our book on Christopher Nolan, my studies of Hong Kong cinema and 1940s Hollywood, and comments over the years on this blog (e.g., Paranormal Activity and Happy Death Day). For more on Into the Woods, go here.

The Last of Sheila (Herbert Ross, 1973). This shot harbors a clue–actually, more than one.

P. S. 18 April 2021: Sondheim has been extraordinarily generous in sitting for interviews describing his creative process, and many are stimulating. Alert reader and master interviewer Brian Rose kindly sent me a link to the remarkable 2020 interview with Adam Guettel that you might enjoy.

1917 and DUNKIRK: A conversation

1917 (2019).

DB here:

For over twenty years, the Willson Center for Humanities and Arts at the University of Georgia at Athens has hosted Cinema Roundtable, a series of film screenings and discussions. Covid-19 hasn’t stopped them from keeping it going, and they kindly invited Kristin and me to visit, virtually, and talk about two war films. The title is “Wartime Suspense in ‘Dunkirk’ and ‘1917’: A Conversation with Kristin Thompson and David Bordwell.”

We discussed aspects of style and genre. Many participants, notably Professor Tanine Allison of Emory, brought up other points about these two intriguing movies. It was also nice to see some old friends from Wisconsin logging in.

The entire session is on YouTube.

We enjoyed participating and thank our hosts, Dick Neupert and Dave Marr. In preparing for the session, I think it’s fair to say we liked both films better on rewatching them.

And no, we haven’t yet seen Tenet. Health precautions keep us at a distance. But we are keen, and when we can write about it, we will.

In a piece of good timing, Tom Shone’s book The Nolan Variations came out three days before our session. It’s excellent and offers the most comprehensive overview of this director’s achievements.

Our e-book on Christopher Nolan is available for download here. (Thanks to those Willson attenders who picked it up!) There’s some background on the book here. Our various blog entries on Nolan’s work are here.

Dunkirk (2017).

Borat: Keep it stupid, simple

Borat Subsequent Moviefilm: Delivery of Prodigious Bribe to American Regime for Make Benefit Once Glorious Nation of Kazakhstan (2020).

DB here:

Defending some of his wildest films, Hong Kong director Tsui Hark pointed out: “Sometimes it’s fun to be stupid.” True enough. But we need to be stupid in sync. When a leader is being stupid and only some of our fellow citizens are, it’s a lot less fun.

The situation invites you to respond with meta-stupidity: Showing how invincibly stupid others are being by doing something stupid yourself. One option is silly satire (Saturday Night Live), but there’s a more deeply disturbing alternative. You can be stupid in a savage, no-holds-barred way.

This can disturb your audience. Shock defeats geniality, obliterates wit. You get called heavy-handed, on-the-nose, over-the-top, and other hyphenated things. You may even move into the realm of the grotesque.

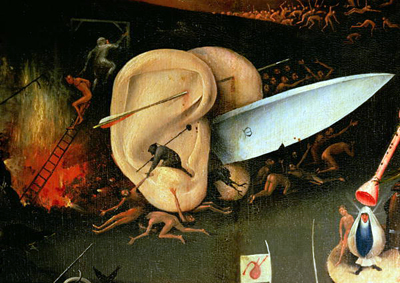

Blunt, tasteless, outrageous grotesquerie has been an important artistic strategy through the millennia. Bosch (below), Bruegel (next), Goya, and other artists have taken exquisite pains to present giddy images of human folly, bursting the limits of taste and sense.

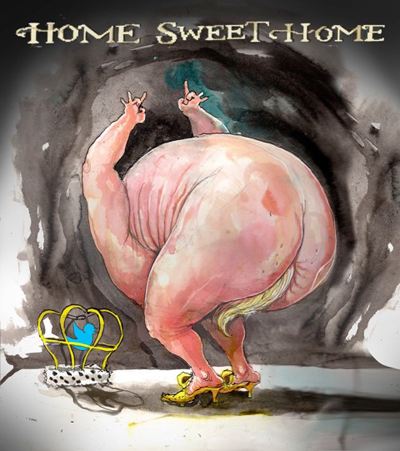

Unsurprisingly, in America the grotesque flourished during the 1960s, in Robert Crumb comix and Paul Krassner’s Disney orgy. Nowadays, Australia’s David Rowe has done fastidious work with slack jaws, skin blotches, and, inevitably, flab.

The realm of the stupid grotesque is one that Sacha Baron Cohen has made particularly his own. It suits our moment.

Friction between parts

The Republican Party’s steamrolling takeover of civil society, begun in earnest in the 1980s but turbocharged under Trump, has created a Golden Age of American agitprop. Responding to the lava flows of vile, vacuous sludge on social media, carefully crafted counterstrikes have shown a fair bit of wit. Call it the spontaneous genius of the American people. That usually comes down to jaunty disrespect.

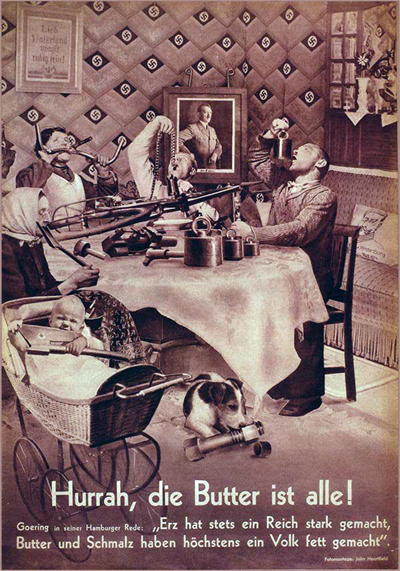

Caricature is the go-to format for those who can draw. But it’s striking that the photomontage techniques of John Heartfield, aimed at an earlier Reich, have been revived for the Age of Trump. Below, Heartfield’s 1933 portrait of Goering as butcher of the Reischstag, alongside an ailing Trump.

Photoshop makes the craft of photomontage easier than in earlier eras, but the trick is still to have an ingenious idea–a play on words, or a reference to a meme. Heartfield’s famous “Hurrah, the Butter’s All Gone!” defiles the guns-vs.-butter motto of classical economics by suggesting that we’re foolish enough to think we can survive on instruments of death. It also quotes Goering’s speech: “Iron has always made an empire strong, butter and lard have, at best, made a people fat.” While suggesting that Hitler’s followers have a hearty appetite for self-destruction, Heartfield has shrewdly created metaphors: handlebars like a corncob, a bandolier like spaghetti, a bomb like a coffeepot, a grenade serving as a doggy’s bone. The baby teething on an axe-blade is a bonus, as are the sprightly swastikas in the wallpaper.

In the gentler example, Trump isn’t just any baby, he’s the kid in Home Alone (covert reference to his cameo in the sequel), with the invaders as both the Blump and, for once, a smiling Bob Mueller.

Note that these aren’t deepfakes, undetectable blends. Montage promotes friction between parts. The juxtaposition bears the traces of the act of bringing disparate pieces together. (Trump’s hands are plausibly small, but that icebag is an awkward fit.) The pieces create a coherent spatial layout, but there’s enough mismatch to remind you of the act of assemblage.

Of course montage is also a film technique, and sometimes–as with the Soviet films of the 1920s, or found-footage films like those by Bruce Conner–we sense a jolt or abrasion between shots. By and large, though, a film like Borat Subsequent Moviefilm: Delivery of Prodigious Bribe to American Regime for Make Benefit Once Glorious Nation of Kazakhstan is less an exercise in montage (despite all its jump cuts) than a faux-documentary mixing the casual norms of prosumer video and quickie tabloid-crime cable fodder.

Instead of the relatively softball treatment of POTUS seen in my images, Borat Subsequent Moviefilm gives us something much closer to Heartfield’s blood and bombs. As in a photomontage, bits of reality are turned into a cartoon that’s outrageous, even offensive. But like Heartfield, Baron Cohen reminds us of one crucial point. Fascism promises to make stupidity fun.

Just another movie?

Spoilers ahead, of course.

The grotesque is usually associated with deformation, but Borat Subsequent Moviefilm has a firm structure. At the risk of sounding silly, I insist that it’s a surprisingly tightly-knit classically conceived film.

The hero starts off with a goal. Ex-journalist Borat Margaret Sagdiyev will get a reprieve from penal labor if he will deliver Johnny the Monkey as a bribe to well-known “pussy hound” Mike Pence. Borat’s daughter Tutar joins Borat in the US by smuggling herself into Johnny’s cargo crate, and because she has eaten Johnny, she must replace him as Pence’s bride.

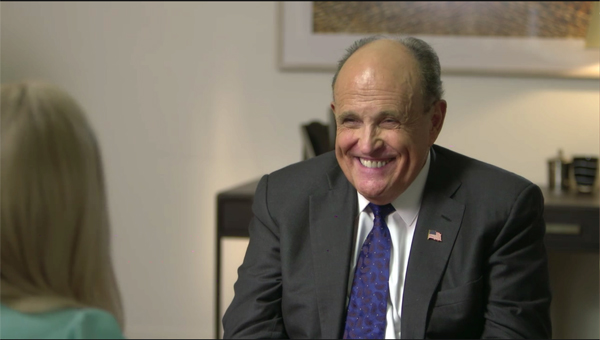

The film falls into the familiar four parts. The setup introduces Borat’s goal and peaks at the invasion of CPAC. As usual, the development section that follows redefines the initial goal. Turned away by Pence’s guards, Borat gets his boss’s permission to offer Tutar to Rudy Giuliani instead. This goal forms the through-line for the rest of the film, as Borat undertakes to make over Tutar into a submissive American woman.

The third section is occupied with various delays and stretches of character change. Tutar starts to liberate herself from Kazach patriarchy and Borat comes to accept his daughter as a person. At the climax, when Tutar decides to offer herself to Giuliani to save her father, he races to rescue her–prepared to sacrifice himself to save her from violation. The epilogue celebrates a new stability with a happy ending, if a worldwide pandemic counts.

The main thread is the familiar device of the naive traveler, the alien who reminds us of how strange our everyday world can seem to an outsider. Borat is introduced to smartphones (though he never figures out the camera), cyberporn, plastic surgery, QAnon, and Covid-19. Tutar learns that her vagina will not chomp her arm, that women can drive cars, and that fathers can walk hand in hand with their daughters.

As in a traditional film recurring motifs–raw onions, a chocolate cake, a plastic baby, strings in the brain–bind the scenes together. Stylistically, the apparently offhand shooting displays classic camera ubiquity. We always have the best view because multiple setups are covering the action (something not common in a true documentary), and probably scenes are retaken. Matches on action are the giveaway.

Many of the scenes, particularly those involving crowds at right-wing events, are made to cohere through the Kuleshov effect. Editing allows Pence to appear to react (stonily) to Borat’s appearance in a Trump fatsuit at the back of the hall.

Think Rudy really inspected these pages of Tutar’s book? He is very moved by receiving it.

And there’s a nice homage to Griffith-style crosscutting, when Borat scrambles to rescue Tutar from the clutches of America’s Mayor.

I grant that Borat Subsequent Moviefilm seems pretty episodic when you watch it, but I suspect that’s partly because of the inherent looseness of a road-movie plot, and partly because of the shock effect of individual scenes. That shock depends, I think, on the relentless grotesquerie on display. Classical clarity of presentation enables the film to chart two major types of stupidity at large in our world.

Leering in bestial degradation

The aesthetic of the grotesque centers on fanciful but disturbing deformation, an exaggeration that’s at once playful and threatening. Art critic John Ruskin, describing the carved heads he found on the Bridge of Sighs in Venice, was appalled to see them “leering in bestial degradation.” That’s not a bad description of Borat Subsequent Moviefilm. The operative word, of course, is leering. The grotesque, as James Naremore points out, mixes fear, disgust, and laughter.

The grotesque breaks categories. Borat’s main disguises as a spare-tired redneck make him implausibly cartoonish. Animals become human (Johnny the chimp is a porn star) and humans become animals, or simply raw material. The producer of Borat’s previous film has been turned into an armchair, with privates preserved.

Species transmogrify. Borat himself–hugely tall, loping like a moose, shitting in front of Trump Tower, with his inane grin and wobbly vocal pitches, high-fiving with hands like seal flippers–is a walking graffito, something you might see scrawled on a remote East European grotto. Tutar, like all Kazakh daughters, is kept in a cage. Grotesque art also breaks taboos. The film wallows in menstruation, incest, masturbation, animated POTUS erections, kinky birth stories, and sex toys, including a gag that pivots on Borat’s accent (Amazon delivers “fleshlights” instead of flashlights). In this context, Rudy Giuliani’s 1200-watt smile becomes wolfishly sinister.

Again, though, narrative processes provide some development. Tutar abandons her cage and (in a sign that Borat is warming to her) joins her dad in the trailer. She becomes a high-gloss Fox-babe interviewer. Borat correspondingly submits to a gender revision, showing up in a bikini to save her from Giuliani. The armor-plated gender roles assigned by Kazakh culture melt a bit in Borat’s odyssey, though again–faithful to the grotesque–father and daughter’s final slow-mo romp through Washington streets is less a lyrical reconciliation after two “character arcs” complete than another bit of tawdry public cosplay.

Eisenstein thought that the grotesque had two registers, the comic (say, slapstick) and the pathetic (say, The Hunchback of Notre Dame). So you could argue that the Borat film moves broadly from the first to settle on the second. In the very last scene, there’s even a hug as a “normalized” Tutar and Borat assume meritocratic professional identities.

Still, this normalization doesn’t really wipe away a cruel Boschian vision of a hellscape seething with grotesques. The film sets up two parallel cultures, Kazakhstan and the USA, each deeply committed to imposing stupidity on its populace.

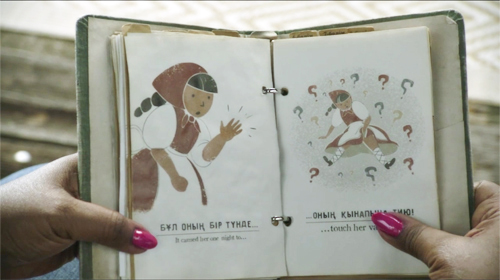

Kazakhstan is a parody of traditional folk patriarchy as recast by a Communist state. Fathers treat daughters as livestock while corrupt officials execute their enemies. Social life is ruled by a guidebook that Tutar dutifully carries everywhere. It details all the powers due to men and all the roles allotted to women, with special instructions about areas they must not touch.

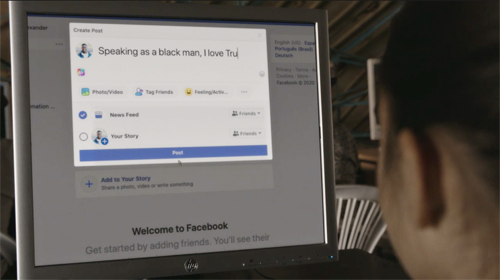

The USA, for all its wealth, is filled almost completely with deadpan imbeciles who advise Borat on how to cage his daughter and gas gypsies. Women instruct Tutar in finding a sugar daddy and behaving at a debs’ ball. True, Tutar learns that the Kazakh manual is bunk, but her new vessel of truth is Facebook, which assures her that the Holocaust didn’t happen.

Armed only with a barbaric yawp, Borat visits anonymous malls and bland bakeries. This moronic inferno houses the pious women of a Republican club, the well-heeled attenders of a CPAC meeting, and Gadsden flag-wavers. As the virus spikes, Borat takes refuge with conspiracy theorists who claim that the Clintons drain children’s adrenaline and feast on blood. Crashing a Second Amendment rally, Borat can quickly teach the audience a song which urges that members of the press be chopped up “like the Saudis do.”

Does an elderly Jewish woman provide a glint of light? After all, she assures Borat that the Holocaust really happened. But the twist is that he’s comforted because her news vindicates his countrymen’s historic role working in the camps. And the image remains pure grotesquerie: a Nosferatu-like Borat measures the lady’s nose, in an echo of the visit to the obliging plastic surgeon who discusses Jewish noses.

If the Kazakhs have been regimented in the service of the state, the American social default is freewheeling, blank indifference. You can tell someone you’re chaining up your daughter, you can send a penis image by fax, you can walk into a conservative gathering in KKK robes, and at best people raise an eyebrow. Stupidity is stolidity. Behind every reaction shot is the unspoken American version of tolerance: Whatever.

The French call us les grands enfants, the big kids. In a country where you do whatever you want until somebody says you can’t (and then you will demand to do it as an expression of freedom), why shouldn’t a man suggest paying for breast implants by letting perverts watch the procedure? (“The perverts,” the staff member explains, “have to be medical personnel.”) Why shouldn’t a birth counselor overlook the father’s apparent confession of impregnating his daughter? You want “Jews will not replace us” squiggled on a cake, with a happy face underneath? No problem. Why shouldn’t the President’s personal lawyer claim on the record that the Chinese invented the virus and deliberately unleashed it on the world? Maybe. Might be something to that. I’m just saying. Check out the retweet.

The most redemptive moments come with Jeanise Jones. As Tutar’s babysitter she nudges the girl away from having breast implants and sets her on the way to thinking independently. Jeanise also teaches Borat that the pain he feels in his heart is love for Tutar. Another way this is a classical movie: Borat Subsequent Moviefilm has its own Magic Negro.

Narrative being narrative, the climax brings a change. Borat returns home, expecting execution, but he learns that his mission has actually been accomplished. His real purpose was to spread the coronavirus, developed in Kazakh labs to punish the world for laughing at the homeland after his first film. He has been the Typhoid Mary of the pandemic (his middle name is Margaret), and with his success Kazakhstan recovers a place of honor in the world community. It has moved forward to the digital age. Instead of playing ostrich, cut off from the outside world, the people are now staffing troll farms.

Now the daughters have joined globalization and have something important to do: overturn American democracy.

And instead of the Running of the Jew, the honorable tradition revealed in the first film, the homeland can afford to look down on a new scapegoat: America. In a colossal magnification of the grotesque, the ballcap hillbilly and the gun-toting Karen terminate Dr. Fauci.

Satire gone gross, pranks and punking pushed to randy delirium: No wonder Sacha Baron Cohen was so suitable for the role of the Yippie Abbie Hoffman in The Trial of the Chicago 7. In Borat Subsequent Moviefilm, I think he has done something important. He has made the 1960s put-on a vehicle of political criticism, by simply demonstrating how scary the pleasures of being stupid can be.

The movie cons its subjects, people say. No, they con themselves, aided by the Whatever principle. It’s not always very amusing, detractors say. Right. The grotesque never is. Being thoroughly stupid isn’t thoroughly fun. We are going to learn this over and over in the days and years ahead.

For enlightening commentary on Heartfield, visit here. On comix, the authoritative source is James P. Danky, Underground Classics: The Transformation of Comics into Comix (Abrams, 2009).

The standard survey of the grotesque is Wolfgang Kayser’s The Grotesque in Art and Literature. Jim Naremore makes the case for Stanley Kubrick as an artist of the grotesque in On Kubrick (British Film Institute, 2007). My quotation from Ruskin comes from p. 26 of that.

On the camera-ubiquity convention of pseudo-documentary, as it bears on The Office, you can see this entry. There’s also this one, on the Paranormal Activity series. The Kuleshov effect is discussed throughout our entries, especially here and in this video.

A noun, a verb, and . . . copping a feel in Borat Subsequent Moviefilm.