Archive for the 'Film and other media' Category

Merrily he rolls along: A belated birthday tribute to Stephen Sondheim

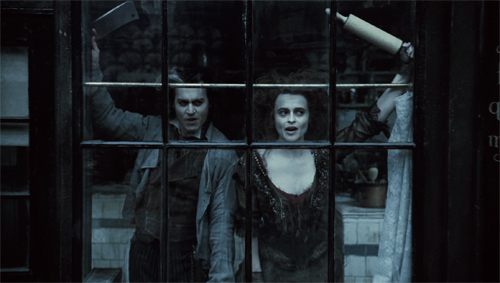

Sweeney Todd: The Demon Barber of Fleet Street (Tim Burton, 2007).

DB here:

Last month Stephen Sondheim celebrated his ninety-first birthday. By coincidence, I just finished a section on him in my current book on popular storytelling.

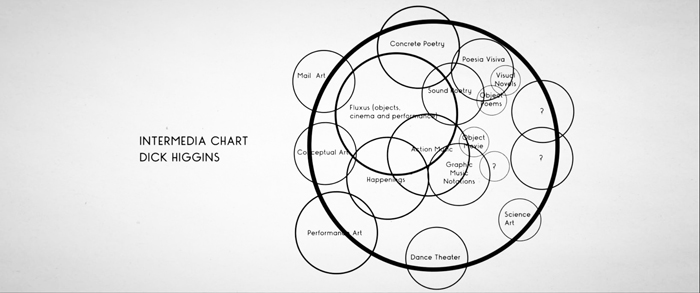

The argument there is that art at all levels, high and low, mass and elite, depends on novelty. That demanded accelerated in the twentieth century, with the explosion of book publishing, magazines, film, radio, theatre, and television. I see this process as a vast energy of crossover. Popular and “middlebrow” storytelling picked up on avant-garde innovations. But it seems to me that modernism, even the High Modernism of Joyce, Woolf, and Faulkner borrow more than is usually noted from conventions of popular storytelling. I hazard the view that it’s enlightening to look at how experimentation, innovations that open new avenues of artistic expression, emerge in mass-audience art.

Nowadays, most intellectuals have found something to love in mass culture. (“We are all nerds now.”) It wasn’t always so. In England and America, the “battle of the brows” had as one consequence the idea that true art, usually typified by High Modernism or the more radical avant-garde, was being squeezed. On one side was mass culture, manufactured as a commodity designed to sooth the masses. On the other was “middlebrow” art, which mimicked the techniques of modernism but made them simple enough for suburbanites to follow. By the 1960s, the people who believed in this trinity were in the minority, partly because they began to realize that centering on the most difficult side of modernism created too austere a prototype of all ambitious art. Irving Howe called this “The Decline of the New.”

Not that everything is a mashup. But I think now we all realize that crossover is a valid expressive option, probably the most pervasive one. The mass media make room for a huge amount of creativity that can’t simply be dismissed as lowbrow or middlebrow. And one reason it can’t is because we can still be excited by unexpected innovations.

Hence the importance of the nearly seventy-year career of a man who confessed a “taste for experiment in the commercial theatre.”

Experiments that are fun

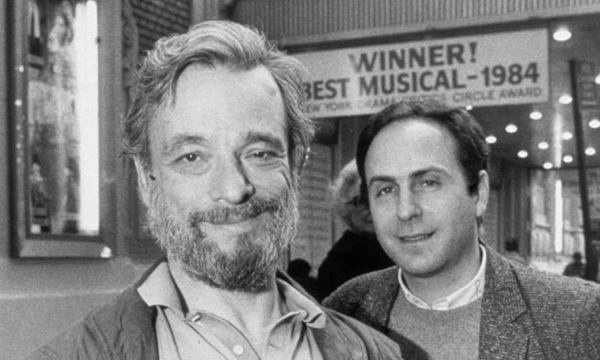

Stephen Sondheim and Leonard Bernstein.

You couldn’t, I think, find a better case for the prospects for experiment in popular culture than his work. His fondness for stage games is part of a theatre tradition we might call “light modernism,” a merging of avant-garde strategies with traditions of popular entertainment. It stretches back to Cocteau’s Parade (1917) and includes the work of Pirandello. Similarly, a trend in British theatre fused aspects of modern theatre (Pinter, Beckett, Ionesco) with the comedy of P. G. Wodehouse and The Goon Show. Tom Stoppard’s Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead (1966) showed that what was “offstage” in one story could constitute the amusingly doom-laden plot of another.

Alan Ayckbourn dedicated his career to formal experimentation with space (three bedrooms as one in Bedroom Farce, 1975) and time (simultaneous action in How the Other Half Loves, 1969). Intimate Exchanges (1983) spreads forking-path plots across eight separate plays and sixteen possible endings. (Two of the variants are on display in Resnais’ films Smoking/ No Smoking of 1993.) House and Garden (1999) consists of two plays performed simultaneously in two auditoriums, with actors dashing between them. Ayckbourn’s most famous cycle, The Norman Conquests (1973) displays a “stacked” structure; each play gathers all the action taking place in one location and skips over scenes elsewhere, which are assembled in the other plays. The audience must construct the overall story, remembering what has happened just before the scene we see now.

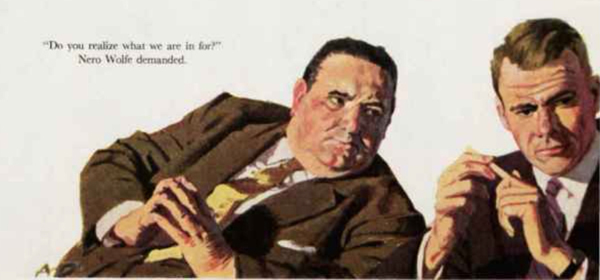

Michael Frayn’s virtuoso Noises Off (1982) probably owes something to Stoppard and Ayckbourn, but it offers its own switcheroo. The opening scene of a sex farce is rehearsed in our first act, is performed skillfully in our second, and collapses in our third view. Crucially, the smooth show of the second act is presented to us in a backstage view displaying the intricate timing involved. Again, an abstract formal concept is mapped onto a conventional scenario, the comedy of a bungled stage production.

Michael Frayn’s virtuoso Noises Off (1982) probably owes something to Stoppard and Ayckbourn, but it offers its own switcheroo. The opening scene of a sex farce is rehearsed in our first act, is performed skillfully in our second, and collapses in our third view. Crucially, the smooth show of the second act is presented to us in a backstage view displaying the intricate timing involved. Again, an abstract formal concept is mapped onto a conventional scenario, the comedy of a bungled stage production.

Mystery plots make useful targets for this sort of popular experiment. Ayckbourn plotted some plays as quasi-thrillers, and Stoppard’s The Real Inspector Hound (1968) is a parody of the country-house murder. Stoppard undercuts the mystery by a Pirandellian device: two critics down in front are commenting as the performance unfolds. This gives Stoppard a chance to mock pretentious reviewing language. The standard whodunit device of reenacting the murder transforms into a replay of the opening act, but now with the critics taking the roles of detective and victim.

Also not surprisingly, both Ayckbourn and Stoppard declared themselves influenced by cinema, a reliable marker of crossover in modern media. Ayckbourn plays were adapted, with ingratiating wit, to film, while Stoppard wrote several scripts, most famously Shakespeare in Love (1998), which if the term means anything must count as defiantly middlebrow entertainment.

Sondheim is on the same frequency as these masters, but has, I think, greater bandwidth. He plunged into cinephilia more deeply. His early musical influences were Hollywood scores, notably that for Hangover Square (1945); Sweeney Todd, The Demon Barber of Fleet Street (1979) was his tribute to Bernard Herrmann. A Little Night Music (1973) and Passion (1994) were adapted from films. Many of his songs refer to movies, and he composed music for Stavisky (1974), Dick Tracy (1990), and other projects. He was even a clapper boy for John Huston on Beat the Devil (1953).

Instead of parodying mysteries, he has been deeply committed to them. Detective fiction is his favorite reading, and as a puzzle addict he has spent hours devising murder games. “I have always taken murder mysteries rather seriously.” Both Company (1970) and Follies (1971) were initially planned as mysteries, with the latter concerned not with “whodunit?” but “who’ll do it?” Sweeney Todd is a paradigmatic revenge thriller. Asked by Herbert Ross to write a film, Sondheim and Anthony Perkins (another admirer of “the trick kind” of mystery practiced by John Dickson Carr) came up with The Last of Sheila (1973).With George Furth, Sondheim wrote a play, Getting Away with Murder (1996), and with Perkins he planned the unproduced Chorus Girl Murder Case, an homage to 1940s Bob Hope movies. The clues would be hidden in the songs.

Fiddling with formula

Sondheim and producer/director Hal Prince (left) during rehearsals for Merrily We Roll Along.

Sondheim’s zest for film and mystery fiction reflects a deep admiration for popular culture. It’s one thing to enjoy it, as Ayckbourn and Stoppard clearly do, while also poking fun at its silly side. It’s something else to appreciate its artistry in depth and try to master the conventions yourself. Despite learning “tautness” from the austere avant-gardist Milton Babbitt, Sondheim took as his mentor Oscar Hammerstein II. Tin Pan Alley, with its finger-snap rhythms and suave wordplay, pushed him toward a brisk cleverness. The virtuoso rhymes in his bouncy “Comedy Tonight” (A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum, 1962) inevitably bring a grin: Panderers! Philanderers! Cupidity! Timidity! . . . Tumblers, grumblers, bumblers, fumblers!

While executing these pirouettes, the song provides a Cliffs Notes guide to Roman New Comedy by contrasting it with tragedy. Tonight, weighty affairs will just have to wait. Sondheim similarly lays bare a convention in his script for the unproduced movie Singing Out Loud, where the couple gradually learn that it’s okay to express emotion in song. “They have to learn to overcome the unreality of it and break into song in the conventional manner of all musicals.”

By taking fun seriously, Sondheim ransacks culture high and low for occasions for experimentation. He was crucially influenced by Allegro (1947), an ambitious Rodgers and Hammerstein musical he considered “startlingly experimental in form and style.” Its use of sliding screens to create “cinematic staging” would become standard in later musicals. He calls Hammerstein “the great experimenter” who used the verse sections of songs to explore possibilities of structure, melody, and harmony.

Sondhim’s breakthrough experiment was Company (1970). It consists of flashbacks framed by the protagonist Robert’s thirty-fifth birthday party. Sondheim claimed it offered “a story without a plot.” The flashbacks don’t supply a goal-directed character arc and instead sample Robert’s bachelor lifestyle and its effects on his three girlfriends and the five married couples in his circle. The result is a compare-and-contrast pattern of parallels. Complicating things further, bits of action are accompanied by a chorus-like commentary from characters not in the scene. Still, there is a certain progression to the whole, indicated by Robert’s disillusioned but faintly hopeful final song, “Being Alive.”

The nonlinearity of Company poimts up Sondheim’s impulse to play with time, viewpoint, and other techniques. Assassins (1990) moves freely back and forth across a hundred years. In Follies characters argue with their former selves. Sunday in the Park with George (1984), built on parallels between two painters, assigns inner monologues to artist and model; characteristically, Sondheim expresses jumbled thoughts by avoiding rhymes. Another duplex structure (Before/ After) shapes Into the Woods (1987), s a virtuoso braiding of classic folktales into a single plot.

Several plays utilize a narrator, who may take a role or converse with the characters. The Narrator of Into the Woods is killed fairly early in the action. Alternatively, Sondheim conceived Passion as an epistolary musical. Characters writing or reading letters operate “somewhere between aria and recitative,” rendering the emotional climaxes as “read rather than acted.” In this excerpt, Giorgio goes to bed with Clara while Fosca is reading his letter breaking up with her. This is a concert performance; in a full production the couple undress on one side of the stage, while Fosca reads the letter. Time floats uncertainly

Working in musical theatre gave Sondheim a layer of implication beyond what Stoppard and Ayckbourn had available with spoken dialogue. A score can evoke earlier scenes through leitmotifs and can enhance characterization. Starting with Anyone Can Whistle (1964) Sondheim created pastiche songs that vary from the show’s overall style. Merrily We Roll Along incorporates cabaret acts (“Bobby and Jackie and Jack”) while Assassins integrates various popular musical traditions, from vaudeville to melodrama. We might think of these pastiches as akin to the “polystylism” of the chapters of Ulysses, which Sondheim strongly admires.

Pacific Overtures (1976), a chronicle of Japan’s early engagements with the west, has the structure of a “portmanteau” film composed of exemplary episodes. It too has a narrator, the Reciter, and its experiments include turning renga linked verse into a passed-along song. The most formally daring scene, “Someone in a Tree,” stages the March 1854 signing of the treaty opening up ports to American ships. We do not see the ceremony, which is held in a secure house.

The Reciter questions an old man who claims that as a boy he watched the negotiations from a tree. During their dialogue, a boy clambers up the tree, and he and his older self collaborate in reporting the event he sees but cannot hear. Then the Reciter discovers a samurai guard hiding beneath the floorboards. He reports what he hears but cannot see. (Beware the YouTube ad at the start.)

As the singers’ accounts intertwine, a moment is assembled through partial perceptions. In a gesture reminiscent of Joseph Conrad’s novels, the event is broken up, made accessible only through partial viewpoints. And only the witnesses attest to the event; without them, we have no access to history. “I’m a fragment of the day./ If I weren’t, who’s to say/ Things would happen here the way/ That they’re happening?” In adapting novelistic techniques for relativistic point of view to the stage, Sondheim, as an experimental storyteller, is ready to plunder any tradition that can yield something fresh.

Form, “content,” and everything in between

Sondheim and collaborator James Lapine.

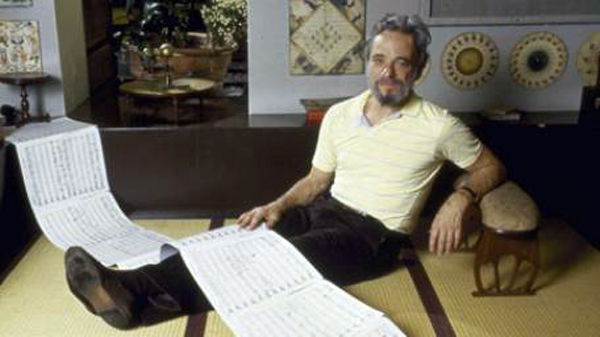

In his invaluable creative memoirs, Finishing the Hat (2010) and Look, I Made a Hat (2011), Sondheim claims as a basic creative principle “Content dictates form.” But his puzzle-addict efforts to seek out difficulties to be overcome makes me think that this is more alibi than axiom.

I’d rather think that like many experimental artists, Sondheim uses “content” (whatever that is: subject matter, theme, bare-bones story) as at best one ingredient and often as a handy excuse. Sometimes audiences need help when faced with radical novelty. People may have been more receptive to Debussy’s daring pieces because of the “atmospheric” connotations of their titles. The stratagem of labeling one movement of “La Mer” as “From Dawn to Noon on the Sea” was pointed out by Erik Satie: “I liked the part at quarter to eleven best.”

Granted that Sondheim tries to suit his words and music to the genre and story he has selected, he often seems to take “content” as a pretext for solving problems he sets himself. Who else would decide to write all the songs for A Little Night Music in waltz tempo, not least for the challenge of avoiding monotony?

I think Merrily We Roll Along is a good example of how, accepting an initial problem, Sondheim complicates matters “unnecessarily.” This largely forgotten 1934 Kaufman and Hart comedy was formally daring: its scenes play out in reverse chronology, so the last scenes we see in the plot are the first events of the story. In adapting the play to a musical, Sondheim created a story of three twentysomethings trying to break into show business.

I think Merrily We Roll Along is a good example of how, accepting an initial problem, Sondheim complicates matters “unnecessarily.” This largely forgotten 1934 Kaufman and Hart comedy was formally daring: its scenes play out in reverse chronology, so the last scenes we see in the plot are the first events of the story. In adapting the play to a musical, Sondheim created a story of three twentysomethings trying to break into show business.

The purported rationale for telling their story backward is that it poignantly traces the loss of youthful idealism. But that arc could be just as poignant laid out in chronological order–or, if you want advance knowledge of how the struggles will turn out, via chronological flashbacks wrapped in a contemporary time frame. The reverse chronology seems both an experiment in whether audiences can follow the string of events and an effort to end a sad story in an upbeat way, with the characters still vigorous and hopeful–while we know what awaits them.

Sondheim faced an initial task of making the time scheme clear. He came up with transitional choral passages by the whole company that signal the shift to an earlier block of time. Different productions experimented with ways of reinforcing these musical tags, such as a synoptic slide show reminiscent of the “News on the March” sequence of Citizen Kane.

But the inverted chronology of Merrily We Roll Along also justifies experiments in musical texture. Because the play is about friendship, melodic motifs are swapped among the characters in their soliloquy songs. Moreover, in a 1-2-3 plot, Sondheim explains in Finishing the Hat, fully vocalized melodies are given reprises, shorter versions of the original number. Sondheim could have followed this convention. Instead, in relentless adherence to the reverse chronology, he made the reprises come first, as appetizers for songs yet to be fully heard. The puzzle addict will try to fit everything together in surprising ways, whether the audience realizes the fine points or not.

Solving one problem can launch a cascade of further problems. To introduce a 1980s audience to the musical ambience of Broadway’s heyday, Sondheim opted to revive the thirty-two bar song that he and his generation had “stretched out of recognition.” But then his penchant for pastiche posed a new problem. How to use that schmaltzy song form not just to satirize superficial characters like Joe the producer but to sustain connection to the sympathetic characters when they express authentic emotion?

Sometimes the problem is set not by “content” but by genre, tradition, or purely practical contingencies. Sondheim embraces show-biz conventions to discover what he can do with them. Hammerstein told him that the opening number can make or break a show, so Sondheim strives for a grabber when he can. The eleven o’clock number, a hangover from the days when shows began at eight-thirty, demands a show-stopping vehicle for the stars–e.g. “Anything You Can Do” in Annie, Get Your Gun. For Anyone Can Whistle, Sondheim wrote “There’s Always a Woman,” a rapid-fire comic confrontation between the two stars Angela Lansbury and Lee Remick, dressed identically. He conceived it as “the eleven o’clock number to end all eleven o’clock numbers.” It didn’t achieve what he wanted (“more like a ten-fifteen”) but it indicates his inclination to display virtuosity in response to purely formal demands.

Look, he made a show

Finishing the Hat and Look, I Made a Hat take us into the artisan’s kitchen–not only the studio or the stage where a team comes together but also the kitchen that’s the mind of the creator, who sweats out as much as possible beforehand. Sondheim shares with us the “choices, decisions and mistakes in every attempt to make something that wasn’t there before.”

This is a rarer accomplishment than you might think. Relatively few artists in any medium have the wish or ability to probe their creative process in detail, from conception to minutiae of execution. There are plenty of artists who talk of story sources and bursts of inspiration, but they seldom get down to the compromises, workarounds, and failed efforts. The best such books on popular storytelling, Sidney Lumet’s Making Movies and Patricia Highsmith’s Plotting and Writing Suspense Fiction, are illuminating, but nothing compared to the multilayered self-consciousness Sondheim brings to the task. He notes: “The explication of any craft, when articulated by an experienced practitioner, can be not only intriguing but also valuable.”

It helps when the artist works in brief, segmented forms, such as the songs that make up a musical. They can be analyzed line by line, and can illustrate the challenges of word choice, rhythm, and rhyme as they relate to the ongoing story, the portrayal of character, and of course the score. This engineering side of construction, basic to popular art, is attractive to a practitioner who happens to be a puzzle fiend. He makes every choice a challenge to his ingenuity.

Take one example, “A Little Priest” from Sweeney Todd. Sweeney has decided to turn his lust for personal vengeance into random barber-chair homicide. This scheme suits Mrs. Lovett’s need to produce better meat pies. The result is a list song, a Sondheim favorite. Here’s the rendition of the Broadway original with Len Cariou and Angela Lansbury, for most of us the definitive version.

The couple deliriously catalogue what citizens might furnish appropriate ingredients. Sondheim’s founding choice: the list will consist not of individuals, who would need naming, but of social types whose titles can rhyme more easily. Sweeney role-plays a customer checking Mrs. Lovett’s imaginary wares.

Todd: What is that?

Mrs. Lovett: It’s priest./ Have a little priest.

Todd: Is it really good?

Mrs, Lovett: Sir, it’s too good, at least./ Then again, they don’t commit sins of the flesh./ So it’s pretty fresh.

Todd: Awful lot of fat.

Mrs. Lovett: Only where it sat.

Todd: Haven’t you got poet/ Or something like that?

Mrs. Lovett: No, you see the trouble with poet/ Is how do you know it’s/ Deceased?/ Try the priest.

Second choice: the song must be constructed so that the rhyming emphasis falls on the types, so the lines end on the name of the profession, as above. Third choice, new constraint: Throughout the play, Sondheim tries for triple rhymes, so one- or two-syllable professions (priest, poet) will allow for that. Fourth choice: the need to build the song out of short lines, which will permit “an increasingly intricate rhyme scheme.” That’s on display here, with priest–least–deceased–priest threaded with flesh–fresh and fat–sat–that and poet–know it.

The song surveys a range of social types, while reminding us of Sweeney’s main target Judge Turpin (“I’ll come again/ When you have judge on the menu”). The climax of the song declares a perverse commitment to equity. “We’ll not discriminate great from small/ No, we’ll serve anyone/ Meaning anyone–/ And to anyone/ At all.” The catalogue culminates in a sprightly celebration of mass murder.

Finicky as ever, Sondheim confesses that he never liked the line “Meaning anyone,” which is a place-filler, but now he says he knows how to improve it.

Why probe the artist’s craft in such detail? Sondheim notes that journalistic reviewers aren’t trained in technique or don’t know the trade secrets; they’re just declaring what they like or dislike. More intellectual and academic critics are inclined to write broad overviews, usually about the cultural sources and effects of the music. A practitioner who explains the cascade of decisions, freely made or imposed from without, can provide something rare. Just as the sports fan enjoys learning the fine points, learning the tricks of the artist’s trade can boost our appreciation. We can learn to enjoy “the spectacle of skill.”

No surprise: I was reminded of the historical poetics of cinema. This approach to film studies tries to analyze how filmmakers draw on the menus of options normalized in particular times and places. In trying to discover principles of craft practice, we seek out any information we can glean from artisans. For this purpose, we’ll not discriminate great from small.

At the movies

Sondheim with Steven Spielberg on the set of the remake of West Side Story.

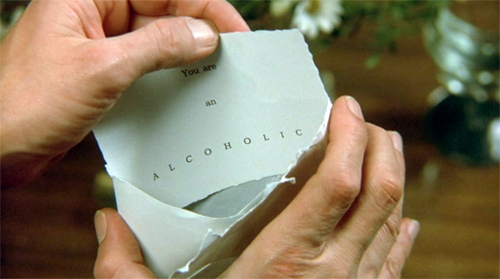

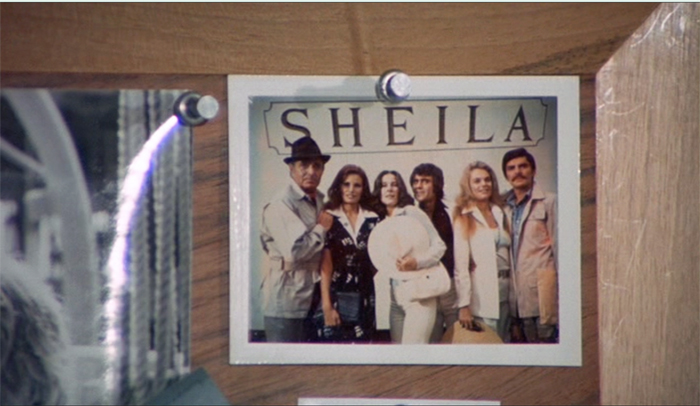

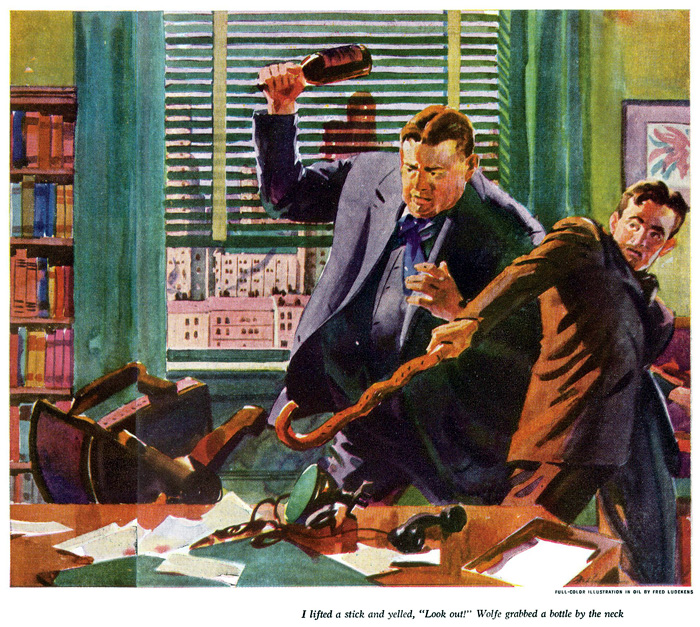

The Last of Sheila is a brittle, cynical satire on the film industry while being a well-designed classic mystery. Sheila Greene is struck down by a hit-and-run driver after she storms out of a party she and her husband Clinton have been holding. Under the promise of a potential movie deal, Clinton gathers six suspects on a pleasure cruise on the French Riviera. Once they’re are aboard, Clinton announces the entertainment: a mystery game. Each guest receives a card declaring a secret, such as “You are a homosexual” and “You are an alcoholic.” Clinton assures them that each is simply “a pretend piece of gossip,” but it becomes clear that the game is designed to expose someone, not necessarily the recipient, as guilty of the card’s charge. Meanwhile, Clinton tries to discover Sheila’s killer.

Every night, at the port they visit, the guests must follow clues to link one of them to a past transgression. The game is interrupted when one of the travelers is killed, and so the survivors embark on their own investigation. As in an Agatha Christie novel, the characters are stock types. There’s the vapid star, her hanger-on husband, the over-the-hill director, the rapacious talent agent, the second-tier screenwriter, and his heiress wife. Again, as in Christie novels like Death on the Nile and Murder on the Orient Express, the yacht cruise isolates the suspects and allows them to debate the identity of the culprit but also also to reveal Clinton’s scheme. In response, the killer has conceived a counterplot for baffling the other guests. Instead of these Christie novels, there is no designated Great Detective to take Hercule Poirot’s place. Any of the people hazarding solutions could be guilty.

In the spirit of the “fair play” detective novel, the audience is provided some clues that flit by, but can be checked on a replay. It’s not a spoiler to note the casual early appearance of an icepick, or the glimpses of some–but not all–of the clue cards.

By contrast, as John Dickson Carr points out, the really skillful mystery writer rubs your nose in the clues. It’s not a matter of a passing mention of the color of a man’s tie, or the way a character pronounced a word.

The masterpiece of detection is not constructed from “a” clue, or “a” circumstance. . . . It is not at all necessary to mislead the reader. Merely state your evidence, and the reader will mislead himself. Therefore, the craftsman will do more than mention his clues: he will stress them, dangle them like a watch in front of a baby, and turn them over lovingly in his hands.

The best example of this tactic in the film is the photograph at the bottom of this entry. The shot lets us dwell on Clinton’s apparently innocuous photo of his guests. Elsewhere the script plays up that old favorite, the discarded cigarette butt.

Sondheim and Perkins’ passion for classic detection is revealed in a long sequence of pure ratiocination. Across twenty-one minutes in the yacht’s lounge, one guest reconstructs the scenario behind Clinton’s game. The layout of space, in both long shots and shot/reverse shot, is quite precise and varied. Of course there are clues in the behavior of certain characters.

Part of the reconstruction turns out to be erroneous, as in the detective-novel convention positing an initial, faulty solution. In all, The Last of Sheila, while memorializing the sort of scavenger hunts and elaborate games Sondheim put his friends through, remains a rare example of an updating of the classic whodunit.

By contrast, the film adaptation of Sweeney Todd is a suspense thriller. The plot doesn’t hinge on an investigation but a pursuit (although that does yield a surprise revelation). Sondheim considers it the only satisfactory film version of one of his shows. “This is not the movie of a stage show. This is a movie based on a stage show.” But then what was the show? Opera? Operetta? No. “What Sweeney Todd really is is a movie for the stage.”

And a grim, brutal one at that. Tim Burton has developed Sondheim’s original through several cinematic strategies. One emphasizes Sweeney’s willed estrangement from humanity. If the stage Sweeney, often played by a large man, has a certain sweeping bravado, Sweeney on film scowls in soft-spoken fury. His puckered brows and pinched lips are set in a face as unearthly pale as a cadaver’s, or a clown’s. This seething little man is presented as virtually locked in his quarters, peering out at the world on which he will wreak vengeance.

Sweeney’s isolation is given a narcissistic cast when he unpacks his razors. He who has no human ties croons to “my faithful friends.”

Mrs. Lovett looks on, trying to secure a connection: “I’m your friend, too.” But he ignores her. Burton provides POV shots of Sweeney’s face reflected in his razor blade, a neat way of showing his self-absorption passing into violence.

At one point, he seems to register Mrs. Lovett’s gestures of affection, and Burton neatly shows the POV reflection shifting to her.

His contemplation of her as an ally can, it seems, only see her as another reflection of himself and an instrument of his vengeance–a tool, not a lover.

He rejects her affection (“Leave me”) and he twists the razor, turning the reflection back to him. He’s still locked in his solitary obsession.

He finishes the song alone, now even more committed to his mission. A final shot shows him gleefully peering out the window at the city he and his faithful friends will ravage.

Mrs. Lovett becomes his genuine accomplice in the song, “A Little Priest.” In the stage directions, Sondheim asks that Sweeney and Mrs. Lovett use pantomime to evoke the meat pies they want to harvest from Sweeney’s customers. In the film, however, the pies she has already made are surrogates for the ones she proposes.

Given the more tangible setting, Burton returns to the window motif; Mrs. Lovett’s shop becomes an extension of Sweeney’s enclosed world. The couple’s list-song takes place with the two of them at the windows, scanning the street for victims. As you’d expect, they spot a priest first.

If the barber shop upstairs is Sweeney’s mission control, the pie shop becomes his supply center. Mrs. Lovett realizes that she can get his friendship only by joining his plan for vengeance, and once he realizes her commitment, she becomes an attractive partner. They pledge their partnership in a rolling-pin waltz, and the sequence ends with a shot that echoes the earlier capstone, but including Mrs. Lovett.

There’s a lot more to be said about The Last of Sheila and Sweeney Todd, but I invoke them just to show that Sondheim’s talents can create robust, innovative, sometimes disturbing cinema.

I could imagine someone criticizing Sondheim as the ultimate middlebrow artist. Adapting foreign films (Smiles of a Summer Night, Scola’s Passion) and Grand Guignol to the American musical; turning Seurat’s Grande jatte into a living tableau (and naming the painter’s model Dot!); imposing games with time and viewpoint on a showgirls’ reunion; investing fairy-tale optimism with sinister implication–all can seem too clever by half. An objector might say that a Sondheim show doses schmaltz and hokum with just enough formal ingenuity to let audiences feel clever. But I think that sort of having-it-both-ways defines a great deal of popular entertainment, and it has its own value. Bergman and Seurat and Little Red Riding Hood remain unharmed by plays that take them as pretexts for ravishing music and cunning theatrical games. Formal ingenuity is not a small thing.

Sondheim opened new vistas for the musical to explore. I suppose you can call Lin-Manuel Miranda’s Hamilton middlebrow too, making rap and hip-hop safe for people who can afford a Broadway ticket. But if you think Miranda opened new paths, note that he thinks that Sondheim pointed the way. He took advice from Sondheim while writing the show, and he paid tribute in a preface to an interview:

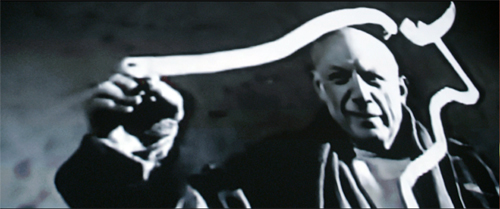

He is musical theater’s greatest lyricist, full stop. The days of competition with other musical theater songwriters are done: We now talk about his work the way we talk about Shakespeare or Dickens or Picasso.

You don’t have to go that far to see that artists at all levels of taste innovate, and their efforts sometimes oblige us to see fresh expressive possibilities in their artforms. If we are all nerds now, we can become connoisseurs of the experimentation–sometimes subtle, sometimes bodacious–that pervades popular entertainment. Sondheim, meticulous and generous and tirelessly exploring, coaxes us to do that.

I’ve drawn most of my Sondheim quotations from Finishing the Hat: Collected Lyrics (1954-1981) with Attendant Comments, Principles, Heresies, Grudges, Whines and Anecdotes (Knopf, 2010) and Look, I Made a Hat: Collected Lyrics (1981-2011) with Attendant Comments, Amplifications, Dogmas, Harangues, Digressions, Anecdotes and Miscellany (Knopf, 2011). Other remarks come from Craig Zadan, Sondheim & Company (Harper & Row, 1994) and Meryl Secrest, Stephen Sondheim (Knopf, 1998). Google Book Search should help you locate my citations by phrase. Steve Swayne provides a thorough analysis of the role of cinema in his career in How Sondheim Found His Sound (University of Michigan Press, 2005), 159-213.

More general books about the craft traditions Sondheim adopts and revises are Philip Furia’s The Poets of Tin Pan Alley: A History of America’s Great Lyricists (Oxford, 1992) and Jack Viertel, The Secret Life of the American Musical: How Broadway Shows Are Built (Farrar Straus Giroux, 2016. I’ve praised and applied Viertel’s account in this earlier entry.

Sondheim discusses the composition of “Someone in a Tree” in this interview with Frank Rich. The second part is especially revealing about Sondheim’s combining music and lyrics through a vamping figure. That accompaniment, detached from the sung melodies, depends on a “gradual change” principle that reminds me of the minimalist music of Glass (Einstein on the Beach, 1975) and Reich (Music for 18 Musicians, 1976) at the same period. A musicologist would probably correct me, but if the affinity holds good it would further show Sondheim’s pluralistic appropriation of many traditions. Thanks to Jeff Smith for discussions of this and for help with other musical matters.

The John Dickson Carr quotation comes from his 1946 essay, “The Grandest Game in the World.” The most complete version of it is in The Door to Doom and Other Detections, ed. Douglas G. Greene (Harper, 1980), 334-335.

Many fine appreciations of Sondheim appeared around his birthday, but I especially like this one by Jennie Singer, packed with clips.

For a long time Kristin and I have studied innovations in popular storytelling, as in her analysis of narrative in the New Hollywood, my book on the same area, her monograph on P. G. Wodehouse, our book on Christopher Nolan, my studies of Hong Kong cinema and 1940s Hollywood, and comments over the years on this blog (e.g., Paranormal Activity and Happy Death Day). For more on Into the Woods, go here.

The Last of Sheila (Herbert Ross, 1973). This shot harbors a clue–actually, more than one.

P. S. 18 April 2021: Sondheim has been extraordinarily generous in sitting for interviews describing his creative process, and many are stimulating. Alert reader and master interviewer Brian Rose kindly sent me a link to the remarkable 2020 interview with Adam Guettel that you might enjoy.

THE TRIAL OF THE CHICAGO 7: Aaron Sorkin samples the menu

The Trial of the Chicago 7 (2020).

DB here:

Love him or hate him, you have to admit that Aaron Sorkin has carved out a unique position in contemporary Hollywood. If we want to understand craft practice from the position of media poetics—that is, the principles governing form, style, and theme in particular historical circumstances—we can usefully look at him as a powerful example.

He’s more than merely typical, of course. In an era when the f-word exchanges of Palm Springs pass muster as comic dialogue, it’s refreshing to watch a movie where smart characters, sparring for high stakes, make a retort that’s more stinging than a slap in the face. These movies are written through and through, and in distinctive ways.

More broadly, Sorkin’s distinctive career invites us to consider the nature of innovation and originality in the popular arts. Because of “progressive” accounts of art history, we’re inclined to emphasize the shock of the (utterly) new as the mainspring of change and the central source of quality. The history of modern painting is written as a series of breakthroughs after Post-Impressionism, from Cézanne through Picasso and Mondrian and so on—the leap to abandon the past, the “next logical step” in an advance toward…what? Abstract Expressionism? Then what? Similarly, from Wagner to Strauss to Schoebberg to Berg to Webern and then…? Boulez? And…?

If the history of an art is a surging procession of avant-gardes, what then do we do with the artists who don’t fit? There are eccentrics, such as Balthus or Satie, who turn out to “point forward” at angles and detours that the linear-progress story doesn’t allow. What about those artists who refine or revise tradition in fresh ways? Where do we put Deineka, recently noticed as no mere Socialist Realist hack, or Shostakovich and Sibelius? Or, in the orthodox history of the detective story (whodunits surpassed by hardboiled), Rex Stout?

In the popular arts particularly, we should expect to find historical patterns less like the Breakthrough Canon, a high-altitude survey of outsize rock formations, than something closer to the ground. Studying mass entertainments like film and popular fiction, we’re likely to find valleys revealing unexpected views of familiar landscapes. There are daisies in the crevices.

In contrast to the Breakthrough account, non-western art traditions valorize accumulation of options and preservation of precedent. An artist earns acclaim for finding fresh ways to realize long-standing craft principles. The Japanese renga poet, the Chinese painter or calligrapher, and the Ottoman carpet weaver revise inherited techniques to reveal new expressive possibilities. Actually, in the West we have the same situation. Come down from the bird’s-eye view, and we’ll see the same fine-grain fluctuations. E. H. Gombrich pointed out how painters, the masters and the minor players, develop their pictures on the basis of inherited patterns—schemas that they have learned and that provide a point of departure for original treatment.

In several places I’ve proposed that filmmakers work with schemas too—pictorial ones, but also narrative ones. The shot/reverse shot technique is a schema, but so is the framed flashback, the four-part plot, and the strategy of beginning your action at a point of crisis.

You see where I’m going with this. Sorkin is worth studying, I think, as a very skilled craftsman. Surveying just a few of his films showed me that he finds ingenious and sometimes powerful ways to rework the schemas from the tradition of American filmmaking—and, of course, from the theatre.

Ventilating the play

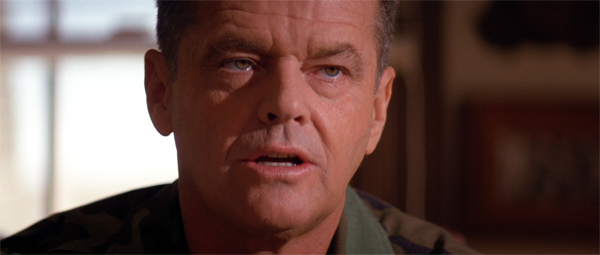

A Few Good Men (1992).

If you want to reach a broad audience in today’s American cinema, you need to either make films with large doses of physical action (as crossover indie directors have found) or to find a signature identity that cultivates a following. In Sorkin’s case, he has dared to rely on plot, dialogue, and a distinct worldview that he has managed to make entertaining. Sorkin’s first plays, followed by the huge stage success of A Few Good Men (1989), typed him as a “theatrical” talent. But over thirty years his film projects sought to “cinematize” what’s usually considered stage technique.

The obvious example is his reliance on “walk and talk,” the long backward tracking shot covering characters striding toward us and spitting out dialogue rapidly. This develops the verbal drama while also yielding some attention-grabbing visuals. But there are less apparent ways Sorkin has blended theatrical technique and cinematic narration.

Early twentieth-century playwrights tended to put the “point of attack”–the moment in the story when you start the play’s plot–fairly close to the climax. Associated with Ibsen and other pioneers of “new theatre,” the late point of attack was a solid convention by the 1910s. As in A Doll’s House and Ghosts, the action starts at a point of crisis, and offstage events leading up to it get revealed through dialogue, sometimes called “continuous exposition.”

The trial schema is a good example of the crisis structure. Typically a trial starts after a lot of stuff has already happened, so the continuous exposition is supplied through testimony and speeches by the defense and prosecution. By 1915, Elmer Rice’s play On Trial was inserting flashbacks that reenacted trial testimony, but some plays stick only to what happens in the courtroom. The Off-Broadway production of A Few Good Men used that linear, present-tense premise, in the vein of earlier plays like The Caine Mutiny Court-Martial (1954) and Inherit the Wind (1955). The investigation of the death of a young Marine is pursued by a prosecution team running up against the military code and a couple of hard-headed officers.

But in preparing the film version, Sorkin adapted to the menu of storytelling options on offer in 1990s moviemaking. For instance, the opening scene could be a grabber, a strong moment that aroused curiosity or suspense. (This might have been a reaction to the need to grab the viewer who’d later see the movie on cable or video.) So instead of letting everything be recounted in the trial, Sorkin’s screenplay for A Few Good Men chose an earlier moment in the story action–a literal “point of attack” showing Dawson and Downey assaulting Santiago.

Later, Sorkin ventilates the play in a traditional manner, supplying scenes that present the prosecutors taking the case and investigating the circumstances. The courtroom scenes don’t begin until about an hour into the film, and they alternate with strategy sessions among the legal team and the defendants. The result is a “moving spotlight” narration, mostly attached to Kaffee the lead prosecutor and Lieutenant Commander Joanne Galloway, but ready to shift to other characters.

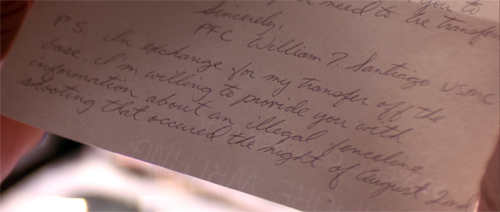

The timeline is chronological, except for a brief flashback dramatizing a letter initially voiced by Santiago. He appeals to Colonel Jessep to transfer him out of the unit for medical reasons. In exchange he offers to give information about an illicit fence-line shooting.

The flashback modulates to Jessep reading the letter aloud (an audio hook) and considering how to handle the situation.

This narration, shifting us from one group of characters to another, gives us a glimpse of the hidden story that the prosecutors need to uncover. The question will become not whether the officers overstepped their authority, but how they will be caught.

After A Few Good Men, we can see Sorkin’s cinematic career as exploring the creative space opened up in the 1990s, a space I’ve tried to map in The Way Hollywood Tells It and several blog entries. For one thing, there’s the matter of how to pick a protagonist.

It seems to me that the film version of A Few Good Men makes Kaffee the protagonist, with Joanne and Sam Weinberg as helpers–just as Jessep is the ultimate antagonist, with Kendrick as his helper. Centering on Kaffee and making him a gifted but glib and cocky young lawyer fits Cruise’s emerging star persona (Top Gun and The Color of Money of 1986, Cocktail of 1988). Sorkin has given us other single-protagonist plots, such as Charlie Wilson’s War (2007), Moneyball (2011), and Steve Jobs (2015).

We may identify Sorkin more with ensemble, or multiple-protagonist, plots because of the fame of his TV shows Sports Night (1998-2000), The West Wing (1999–2006), Studio 60 on the Sunset Strip (2006–2007), and Newsroom (2014-1016). A long-form series permits constant shifting of the protagonist role across a season. But in feature films, I think, a genuine equality among several protagonists is more common in “network narratives” than in crowded films like The Women (1939) and Ocean’s 11 (2001). In the latter, there tends to be a “first among equals”: one or two main characters whose fates are most important, even if subplots centering on others are woven in. Such is the case, I’ll argue, with The Trial of the Chicago 7.

Scanning the menu

Molly’s Game (2017).

Sorkin’s preferred artistic strategies emerge even more clearly, I think, in his handling of narrative structure. He has more or less systematically surveyed a range of storytelling possibilities.

Politically liberal but narratively conservative, The American President (1995) presents an utterly linear plot. As in other romantic comedies, the central couple shares the protagonist role. Their relationships change as they make decisions and respond to external forces. The film plays out the familiar Hollywood double plotline of love versus work: political pragmatism threatens the President’s affair with a lobbyist for environmental reform. There are no flashbacks or fancy time-juggling, and the dialogue is classic flirtation, wisecrack, and one-upsmanship. The one “Fuck you!” becomes a shocking turning point, a test of friendship.

The crisis structure in The American President is presented as a race against time to line up support for two White House bills. Moneyball (2011) creates a comparable pressure on its protagonist. After his baseball team’s loss and the departure of his top players, Billy Beane faces the need to rebuild his roster for the new season. In a classic problem/solution plot layout, he finds a helper in statistician Peter Brand. Again, the plot is mostly linear, though interspersed with summary montages of sports coverage and brief flashbacks to Billy’s own failed ballplaying career.

The fragmentary flashback that carries its own mystery was a common technique of 1990s cinema (e.g., The Fugitive) and remains a standard tool of filmic storytelling. Sorkin’s films use it often, usually to gradually reveals what’s driving the protagonist’s struggle. A version of “continuous exposition,” the flashback allows deeper character revelation; it can liven up the more static sections of the film; and it can provide its own little mystery revelation. In the Moneyball flashbacks we see Billy recruited, decide to give up a college career, and then face failure. This shows how he could have empathy for the second-tier players who are cast aside–and whom Brand’s moneyball algorithms give a second chance.

The time structure is a little more complicated in Charlie Wilson’s War. Here Sorkin samples another option in the schema menu. The story’s crisis is over; the plot starts at the epilogue. After a credits-sequence montage, we’re taken to a CIA awards ceremony, at which Charlie Wilson is honored for working strenuously against the USSR for thirteen years. This scene turns out to be a frame around an extensive flashback.

What follows deflates this high-flown tribute, as we go back to 1980 and see the reprobate congressman pressured into helping the Afghan people by finagling clandestine US investment in fighting the occupying Soviet troops. Other subplots, including an investigation of Charlie’s partying ways, are interwoven. The long flashback concludes and the film’s final sequence returns to the ceremony, with a replay of a grinning Charlie getting his award. The ABA structure makes the whole public event a charade, underscored by a final title: “And then we fucked up the endgame.”

By contrast, Molly’s Game is more fragmentary. We start with a teenage Molly Bloom in a skiing competition qualifying for the Olympics, but an accident knocks her out of the running. This early passage is in turn interrupted by brief flashbacks to earlier in her childhood, of other competitions and accidents and recoveries, overseen by her demanding father. Her first-person voice-over fills in the background, echoing the fact that the story is drawn from the book she’s written (both in real life and in the film).

“None of this has anything to do with poker,” a title ironically informs us, but it’s a tease. This prologue, mixing scenes from phases of Molly’s girlhood, characterizes her as having tenacity, determination, and not a little rage at her dad. Then the present-day action starts, as usual at a crisis. Molly is wakened from sleep by the FBI arresting her for illegal gambling. What has happened in the meantime? Even after the scene of her arrest, the film’s narration wedges in a VHS interview with young Molly in which she’s asked about her goals.

The revelation of the formative years, saved for late in Moneyball, is put up front in Molly’s Game. But now there’s a mystery: How does a promising athlete become a gambling queen?

The question is answered through another series of time shifts, and these occupy the bulk of the film. After Molly’s arrest, the narration fills in her arrival in Los Angeles and her job working for a sleazy entrepreneur who arranges poker games for rich men. Her rise in the world of underground gambling is intercut with present-time scenes of her consulting an attorney to take her case–a risky proposition, since her customers include Russian mafia. And the alternation of her legal problems and her gambling career continue to be interrupted by flashbacks to her as a little girl, as a teenager, and as witness to her father’s infidelities.

Sorkin has layered his plot within several time zones: present, immediate past, and distant past, with the earliest one including scenes scrambled out of chronological order. Again, the purpose is to reveal character motivation. The flashbacks suggest sources of Molly’s decision to triumph over weak men–perhaps, it’s suggested, as revenge for her father’s mistreatment of her and her mother. The time jumps also reveal her as a fierce competitor unwilling to give in. Athletics, it turns out, has a lot to do with poker.

The network as character prism

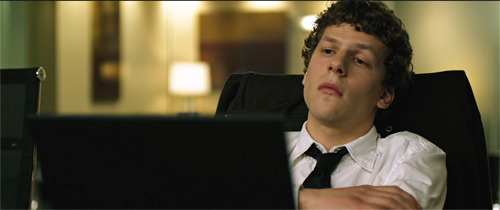

The Social Network (2010).

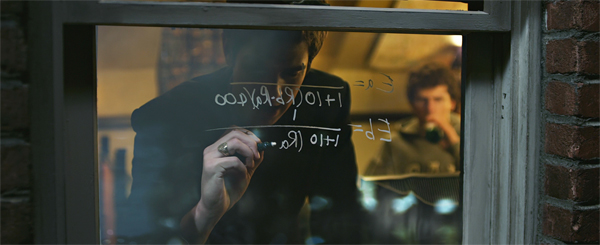

If there were a simple progress in Sorkin’s exploration of the menu of options, you’d expect that The Social Network would come later than it does. Yet before Molly’s Game yielded three principal time layers (the legal case, the career rise, the girlhood), Sorkin’s screenplay tracing the rise of Facebook had already fielded something more complicated than that.

Still trying variants, Sorkin this time puts the motivating moment, the incident that drives the character, at the front of the film. In 2003, Mark Zuckerberg is on a date with Erica Albright. His arrogance provokes her to break up with him. In a burst of pique, he turns a blog into a page that denounces her and asks readers to rate local women. With the reluctant help of his friend Eduardo Savarin, the site crashes the Harvard server and Mark faces disciplinary action.

At this point the film splits into more time-tracks, again transmitted through legal proceedings. The Harvard disciplinary hearing is filtered through a deposition responding to Eduardo’s lawsuit against Mark, long after their partnership has collapsed. Sorkin could have picked this testimony as his point of attack for opening the film, then flashed back to the origins of the suit. Instead, like Molly’s Game, The Social Network starts its plot in the past, skips ahead to the future, and then fills in more of the past.

A second lawsuit is in progress, this time from the Winklevoss twins, and a second string of deposition scenes. Apparently more or less simultaneous with the Eduardo sessions, these also anchor us in an approximate present and cue up incidents in the past. For instance, in a past scene, after an ally of the twins tells of Mark’s successful webpage, the narration cuts to the opening of the Winklevoss case’s depositions, and then back to the brothers recruiting Mark to work on their project.

The dual-track depositions in the present allow Sorkin not only to segue into illustrative scenes in the past, but also to set up crosstalk between the two lawsuits. Immediately after Mark dodges questions from the Winklevii, we see him dodge questions in Eduardo’s session.

By the 2000s, audiences trained in the time-shifting of the 1990s could follow these quick alternations. It’s also up to the director to keep us oriented through differences in costume, angle, lighting, color design, and other elements.

If you take the opening portion as what sets the narrative Now, you could call the deposition scenes flashforwards. Alternatively, you might consider those scenes as Now, although the opening orientation to them has been deleted. Either way, Sorkin has provided a flexible, dynamic structure that allows us to study Mark’s behavior and others’ responses to it.

One of the dreams of storytellers who embraced multiple-viewpoint plots was the idea of letting us see different, even contradictory facets of a character. The prospect was broached by Henry James (in his novel The Awkward Age) and Joseph Conrad (in Lord Jim, Chance, and other books). On the stage, Sophie Treadwell had experimented with it in The Eye of the Beholder (1919). Herman Mankiewicz and Orson Welles played with the possibility of such a “prismatic” narration in Citizen Kane, perhaps as a result of Mankiewicz’s unproduced play about John Dillinger.

By using the trial schema a storyteller can present a character’s public self-presentation, the impression management that tries to win adherence. But the fact that different people testify about a situation also offers prismatic possibilities. Here, the chief contrast is between Mark’s snotty recalcitrance at the counsel table and his swagger in the past.

During the film’s opening, when Mark confides in Erica and Eduardo, we’re about as close to penetrating his mind as we’ll get in the film. Later the film’s narration offers less a study in how his mind works than a portrait of how he handles people–his social survival strategies. The range runs from sheer bluster, as when he tries to overwhelm Erica, through awkward acceptance of class ambition when he meets the Winkleviii, to evasion, threats, and bumbling efforts at friendship. At the end, he goes flat and legalistic, telling Eduardo: “You signed the papers.” The film’s denouement arrives when Eduardo’s lawsuit is launched. “Lawyer up, asshole.”

The opening sections began in the past, but the ending leaves us hanging in the present. At a pause in Eduardo’s suit, the film concludes on the image of blank-faced Mark staring at his monitor. Isolated by his betrayal of the one person close enough to have been a friend, he’s checking Erica’s Facebook page.

This conclusion lets us imagine that sexual and romantic frustration, exposed in the opening, have reinforced Mark’s low-affect aggressiveness. It’s also a suggestion that his slightly vampirish predation suits him for the age of the social network. But we’ll never be sure, because his disdainful indifference is his armor against everyone he encounters.

As with Molly’s Game, this cluster of parallel timelines is intelligible and forceful as a revision of a schema (present/ past/ present) that we know well. And careful cutting, sound work, and performance have kept us on track throughout.

End to end control

Steve Jobs (2015).

In films that don’t rely on chases, fights, explosions, time travel, fantasy, or extraterrestrials, what can hold your interest? For one thing, snappy talk. The old theatre adage claims that dialogue needs to do one of three things: advance the action, delineate the characters, or add humor. Sorkin’s dialogue does all of them at once.

Steve Jobs is braced by his assistant Joanna while he frets over a press story.

“’The only thing Apple’s providing now is leadership in colors.’”

“Don’t worry about it.”

“What does Bill Gates have against me?”

“I don’t know, you’re both out of your minds. Listen to me–”

“He dropped out of a better school than I dropped out of . . . but he is a tool bag and I’ll tell you why.”

“Make everything all right with Lisa.”

“You know–Joanna–boundaries.”

“You’ve come to my apartment at 1 AM and cleaned it, so tell me where the boundary is.”

“There, let’s say it’s there.”

“If I give you some real projections, will you promise not to repeat them from the stage?”

“What do you mean real projections? What have you been giving me?”

“Conservative projections.”

“Marketing’s been lying to me?”

“We’ve been managing expectations so that you don’t not.”

“What are the real projections?”

“We’re going to sell a million units in the first ninety days. Twenty thousand a month after that.”

Each reply shows that a strong line is like an arrow–feathered at the top, barbed at the tip. If your conflict is psychological, then the last part of the line should land with a punch. “We’ve been managing expectations so you don’t not.”

But the lines don’t exist in isolation. Every stretch of the film is a vivid lesson in whipping together bits of earlier conflicts, jumping from one to another as Jobs parries and ducks and changes the subject, all the while tension rises. One issue is picked up (Steve’s reaction to press coverage), interrupted by others (his rivalry with Gates, his friction with his daughter), followed up by a long-running relation with Joanna (“boundaries”), then a big piece of information: one goal, a sales target set in the first segment, has been achieved. But the others are left dangling, to be revisited, and we are looking forward to that.

This sort of repartee brings back the era of snappy chatter. The exchanges recall the films set in rehearsal halls (Footlight Parade), news offices (His Girl Friday), movie studios (Boy Meets Girl), gangster cafes (All Through the Night), and even a research institute (Ball of Fire). A few films of recent years, such as The Paper, successfully recapture the exhilaration of such fast, pungent dialogue. Sorkin delivers it consistently.

Steve Jobs is one of Sorkin’s most structurally ambitious projects. Here he tries out another menu item, that of block construction. In this layout, we get two or more marked-off chunks or chapters, sometimes without the same characters. Block construction came into fashion with Mystery Train (1989), Slacker (1990), and other indie works, and it remains a basic resource for Tarantino and Wes Anderson.

As ever, Sorkin rewrites the block premise as a drama convention, the division into spatially and temporally confined acts. The plot of Steve Jobs is organized around three public product launches: in 1984 (the Macintosh), 1988 (the NeXT Black Cube), and 1998 (the iMac). Each event teems with crises large and small, public and private. They’re all parallel, in that we see the few minutes of preparation leading up to the curtain-raising. Like a party or restaurant scene in a play, a product launch offers a confined space in which characters and story lines can mingle. The pressure of a product demo allows Sorkin to create deadlines and motivate many walk-and-talk passages through backstage corridors.

Just as theatrical is the flow of people into and out of Steve’s presence. From act to act the same associates are ushered into Steve’s presence: his former romantic partner Chrisann, his business partner Steve Wozniak, John Sculley, engineer Andy Hertzfeld, a journalist, and Lisa, the daughter that Steve is reluctant to acknowledge. The French phrase liaison des scènes, “scene linkage,” captures the way that within a single setting characters’ entrances and exits break the act into distinct pieces.

In addition, Sorkin doesn’t confine his time frame to the duration of the demos. As in other films, flashbacks interrupt the present. The 1984 segment uses only one flashback, a visit to garage-hacking days that sets up the dispute about open and close architecture. The flashbacks thicken in the second segment, which reveals the conflict that led Steve to break off with Sculley. That quarrel in the past is tightly crosscut with their confrontation in the present, and as the tension builds one man in the present is replying to an objection in the past. This rapid pacing is one way a “theatrical” premise can hold an audience accustomed to action movies.

Like Fincher’s intercut depositions in The Social Network, Danny Boyle’s handling keeps us oriented through staging, costume, color, lighting, and shot/ reverse shot eyelines.

The block most saturated with flashbacks is the third, the one launching the computer that brought Apple to marketplace triumph. This chapter incorporates glimpses of scenes shown in the first two segments, along with revelations of Steve’s first approach to Sculley. This last recollection is prompted by his admission that he long ago found the biological father who gave him up for adoption. (Many of Sorkin’s protagonists have Daddy Issues.) Again, a big revelation about character motivation is saved for a flashback late in the film.

In addition, other crises come to a head. Steve appears to break definitively with Wozniak, and he reconciles with Lisa, whom he hasn’t, after all these years, fully taken into his life. As he achieves his goals–a successful computer at last, a settling with Wozniak and Andy, and a tentative accceptance of Lisa–he displays more chastened and cautious behavior. He has admitted his fallibility (he was wrong about the Time cover), he has realized what he lost in challenging and trashing Sculley, and he’s ready to move to the next challenge (“music in your pocket”). True, he treats Woz brutally, but Woz gets the final word: “It’s not binary. You can be gifted and decent at the same time.” Steve doesn’t change completely; he just gets a bit more human.

Interestingly, these cadences fit the four-part structure that Kristin’s Storytelling in the New Hollywood has revealed governing many classical plots: Setup, Complicating Action, Development, and Climax, followed by an epilogue or tag. Sorkin has “cinematized” his three “acts” by letting the final one harbor Development, Climax, and an epilogue.

Kristin also points out that classical film story telling relies on motifs that weave their way through the film. Not only music but lines of dialogue and images recur to point up repeated actions, indicate changes in character, or add humor. (A running gag is a comic motif.) Yet movies didn’t invent this tactic. Novels, poems, and plays rely on recurring motifs. Macbeth circulates imagery of blood and ill-fitting garments, while The Importance of Being Earnest wrings a lot out of the mysterious word “Bunbury.”

Steve Jobs is packed with motifs, far more than most movies I can think of. Some bounce around one segment and into another, and several come back at intervals in all three. All the characters relitigate old complaints, and Steve masterfully deflects a conversation by returning to remarks he’s made before. Here’s a partial list of items that are recycled again and again.

Starting exactly on time, the controversial SuperBowl ad, the need to turn off the Exit signs, a bottle of ’55 Margot, the Time cover, the purported treachery of Dan Kottke, “a million in the first 90 days,” “I don’t have a daughter,” 28%, Woz’s request to acknowledge the Apple II, “playing the orchestra,” closed versus open systems, the name Lisa, “end to end control,” 2001, “a dent in the universe,” slots, Pepsi, the psychology of adopted kids, “You get a pass,” the threat of a press release, and “which Andy?”

For Sorkin, even “Fuck you” becomes a motif rather than a space-filler.

A significant cluster involves the arts, particularly music and painting. In their quarrel the two Steves compare themselves to the Beatles, and Bob Dylan’s image and songs float through the movie. This association with the arts helps offset the unpleasant side of Jobs’ temperament, his crisp, frosty bullying of others and his relentless imposition of his “reality distortion field.”

Another motif softens him a bit: his desire to bring computing to kids. The prologue, in which Arthur C. Clarke is interviewed about the future of computing, sets up several motifs–the idea of separating oneself from others (Steve in a nutshell), the importance of home (associated with Chrisann’s demands), and particularly childhood. The reporter interviewing Clarke has brought his boy along, and they discuss how a new generation will quickly grasp the power of personal computing.

That motif is dramatized when, at first indifferent to five-year-old Lisa, Steve uses her as a demo to show Chrisann what the Mac can do. But his interest rises when Lisa intuitively understands that she can draw with it. “Lisa made a painting on the Mac,” he says thoughtfully. He seems to realize that she could be his brainy daughter, and he resolves to put her in a good school. Her drawing looks forward to Picasso’s swooping dab at a bull in the climactic montage of the 1998 launch.

The ping-ponging motifs are mostly in the dialogue, though. They push the action forward, recall earlier moments, and characterize the combatants while also yielding some laughs. Above all, the motifs chart Jobs’ character arc. We know that he’s more committed to Lisa at the end when he breaks his routine and says he’s willing to start the performance late. Soon he will reveal that he has saved her painting to give to her.

In The Way Hollywood Tells It I call Jerry Maguire a “hyperclassical” movie–more classical than it needs to be, flaunting a virtuosity of construction and motivic echo. I vote for Steve Jobs as another instance. Sorkin has used cinema to multiply motifs to a higher power.

Exporting ideas across state lines

The Trial of the Chicago 7.

One innovation of turn-the-century-theatre was the so-called “drama of ideas” or “problem play.” Ibsen, John Galsworthy, and Bernard Shaw sought to break away from standard intrigues of mystery and romance in order to dramatize women’s rights, labor struggles, and other social issues. Sorkin, with his liberal political bent, has brought that legacy to his film work. The subjects and themes he tackles have become as distinctive a marker of his work as any strategies of form and style.To be more precise, his formal and stylistic strategies work upon the ideas he wants to put forth.

How much private life is a US President entitled to? What is the duty of a politician who wants to enact social change? For a tech entrepreneur, where does idealism end and domination begin? Why should a woman not be able to compete on equal terms with men? Does social change come best through reform (reason, the ballot box) or revolution (change of consciousness)? Something like this last occupies him in The Trial of the Chicago 7.

The problem at the center of the film is: How to protest, and eventually stop, US involvement in the Vietnam war? The film’s prologue and epilogue announce the sweep of the issue. It begins with President Johnson ramping up troop commitments and establishing the draft lottery, all during a wave of assassinations. The film ends with Tom Hayden reading out the names of troops who have died while the trial was dragging on. Early on, Rennie Davis establishes the list because it’s “who this is about.”

The defendants in the trial are only loosely associated. Bobby Seale doesn’t know the others and was in Chicago just four hours; he’s also denied counsel. Sorkin carves out two major factions. Tom Hayden and Rennie Davis, as student activists out of SDS, are presented as preppy intellectuals, committed to antiwar action within the frame of protest and legal debate. Abbie Hoffman and Jerry Rubin, associated with the Yippies, are countercultural provocateurs. They anticipate a spectacle of innocence attacked by those in power. They will show the Chicago Democratic convention to be staged, as Walter Cronkite says at the end of the opening montage, in “a police state.”

Although Tom’s and Abbie’s factions communicate a little before the events, it’s the pressure of circumstances in Grant Park that pushes them into dispute. Alongside them Sorkin develops subplots that suggest other political alignments. David Dellenger’s commitment to nonviolence is tested by the flagrant repression of Bobby Seale. Richard Schultz goes along with orders to prosecute, knowing that the case is trumped up. Jerry Rubin falls briefly in love with an undercover policewoman. Fred Hampton tries to help Seale, only to be killed. Attorney William Kunstler discovers that he has a surprise witness to call. Editor Richard Baumgarten notes that in cutting all these lines of action together: “I feel like one of the great successes of how this film unfolds is that each of the characters does have a moment, or multiple moments.”

Tom and Abbie emerge as the “first among equals” because they most sharply articulate alternative accounts of what they’re facing. They aren’t dual protagonists, like a romantic couple tackling common problems. They’re at odds throughout. On the first day when Tom tries to get agreement on goals, Abbie challenges him.

Early court scenes show Tom annoyed by Abbie’s antics, but neither is really an antagonist for the other. Tom can half-humorously admit that he got a haircut to impress the judge, and clearly Abbie admires Tom. The antagonists are the government prosecutors and Judge Hoffman. Tom and Abbie function as what Kristin calls parallel protagonists. Like Mozart and Salieri in Amadeus, or Captain Ramius and Jack Ryan in The Hunt for Red October, they are at once opposed to one another and fascinated by each other. They both compete and cooperate.

What does each one want? This will become part of the drama’s problem, because the two men will be charged with coming to Chicago to stir up violence. Sorkin shrewdly postpones the question in the opening montage that brings some main players together through crosscutting. Incomplete dialogue hooks make their goals somewhat mysterious.

Tom: Young people will go to Chicago to show our solidarity, to show our disgust, but most importantly–

Abbie: –to get laid by someone you just met. . . .We’re going peacefully, but if we’re met there with violence, you better believe we’re gonna meet that violence with–

Dellenger: –non-violence. Always non-violence and that’s without exception. . . . (asking his son what to do in the face of police:)

Dellenger’s son: Very calmly and very politely–

Bobby Seale: –Fuck the motherfuckers up!

Seale’s capper would seem to negate the nonviolence of Dellenger’s position, but at the end of the montage Bobby refuses the pistol his colleague Sandra offers him. “If I knew how to use that, I wouldn’t need to make speeches.”

Unlike Dellenger, he’ll hit back if attacked first. So now only the positions of Tom and Abbie remain undefined.

Eventually, Tom exposes his rationale. If they can prove they were peaceful demonstrators within their rights, it will help “to end the war and not fuck around.” That demands treating the trial seriously. “We as a generation are serious people.” And he doesn’t want to raise police culpability. “We’re protesting the war, not the cops.”

From the start Abbie insists that the trial isn’t a matter of law but of contingency. “This is a political trial.” They were chosen to be examples, and the two lesser defendants are “give-backs,” people the jury can let off with a clear conscience. Abbie and Jerry came to Chicago knowing that police violence was very likely. (Cronkite said so too.) The best way to prove state oppression is to lay it bare, preferably with gonzo humor. After all, the whole world is watching.

The film’s structure supports Abbie’s analysis. Sorkin’s narration, using a moving-spotlight approach, has from the start tipped us that Attorney General John Mitchell has ordered Schultz to prosecute the 7 on flimsy grounds. Mitchell, a spiteful conservative, wants to crush antiwar protest, but he’s also petty. He’s miffed that Johnson’s AG Ramsey Clark insulted him on the way out of office. Mitchell has assembled a mixed bag of antiwar activists to charge with conspiracy. (In an ironic twist, they conspire most successfully after they have been thrown together for trial.)

So the problem play becomes a progress toward understanding political power. Tom Hayden (and to a lesser degree Kunstler) come to grasp the reality of an engineered police provocation and a show trial. Abbie’s privileged insight is further stressed by the fact that he’s the only character given a narrator role. Sorkin interrupts the trial with shots of Abbie at a mike in a club, telling the story of the fights during the riots, correcting the false testimony of the cops. In stage tradition, Abbie is the raisonneur, the explainer.

The conflict between Tom and Abbie gets specified gradually, sharpened in strategy sessions where Tom berates the Yippie contingent for clowning. If progressive politics is branded as childishness, “We’ll lose elections.” Abbie calmly replies that “We’re going to jail for who we are.” The debates are about tactics as well. Tom wants the demonstration to keep away from the convention hall, while Abbie insists that they go downtown. As it turns out, the police squeeze them out of the park and force them into a trap that yields the spectacle that Abbie and Jerry anticipated.

Through crosscutting Sorkin again creates several layers of time: the runup to the convention, the protests themselves, the trial, and a more unspecified moment when Abbie is at the microphone narrating. More linear than the time mosaics of Molly’s Game and Steve Jobs, the Chicago 7 array might seem a step back toward the classic trial schema. Basically, the court proceedings frame the flashbacks to the purported crimes.

The relative linearity is needed, however, to allow us to chart the progress of the parallel protagonists. In a neat balancing act, Sorkin dramatizes character change with Tom Hayden and character revelation with Abbie Hoffman.

Hayden’s character arc traces his realization that the trial is rigged. He has brought table manners to a revolution. He presents a wholesome appearance, and when pressed by Bobby he half-admits he’s rebelling against his upbringing. (Daddy Issues again.) Even his “reflex” action of rising when His Honor enters, violating the pact among the 7, shows that the impulse to behave well is struggling against his sincere urge to end the war through citizen action.

Yet Tom has an outlaw side as well. He releases the air from the tire of a cop car to allow Rennie to escape surveillance. At the climax, seeing Rennie beaten, he calls for blood to flow through the city–not, he tries to explain, the blood of others, but the blood freely given by the protesters. Still, he joins forces with Abbie, Jerry, and Dellenger as they are lured onto the footbridge and into the cops’ trap. The cops, having choreographed the street assembly, push them through the tavern window.

Tom, our main viewpoint vessel in the film, also visits Ramsey Clark with his attorneys. It’s then that he realizes the trial is Mitchell’s political charade aiming to override Clark’s decision not to prosecute the demonstrators. So, after Clark has testified (and sees his testimony suppressed by Judge Hoffman), Tom can redeem himself.

Judge Hoffman has offered Tom clemency before he makes his final statement. The good boy who had asked, “Why antagonize the judge?” rises in polite defiance to read the names of the dead. He will take the same punishment meted out to the others. He now understands revolution as spectacle.

So there’s a little of Abbie in Tom. In the same final stretches of the film, we learn that there’s a little of Tom in Abbie. Tom had planned to testify, but he can’t justify what he said on tape. So Abbie takes the stand. His slapstick persona drops. Behind the Jewish Afro and the wisecracks is revealed an intellectual who can quote the New Testament and gently praise Tom as a patriot. Schultz questions him: Was he hoping for a confrontation with the police? “I’ve never been on trial for my thoughts before.”

As in the opening montage, Sorkin cuts away before Abbie answers, and his pause and grave demeanor let us consider that for all his bravado, he has regrets about the crisis he saw coming.

Like any problem play, The Trial of the Chicago 7 can be criticized for stacking the deck, or oversimplifying, or recasting the problem in ways that favor certain interests (e.g., white college-educated men). But that critique is the risk artists run all the time, even in the most anodyne “nonpolitical” work. If critics study how films achieve their effects, viewers can be more aware of how the schemas we know are shaped by the movies we see and get a clearer sense of means and ends, purposes and fulfillment.

At the same time, artisanal skill in a robust tradition is intrinsically worth analysis. That analysis can reveal new possibilities in what cinema can do. In The Trial of the Chicago 7 Sorkin creates a dramaturgy that embodies ideas in characters’ conflicts, changes, and hidden facets. Once more a theatrical premise has been turned into classically constructed cinema. Sorkin’s work offers one way that this tradition can stay fresh–not through shocking breakthroughs but by highly skilled reworking of schemas accessible to a broad audience. You know, the way theatre used to be.

Thanks to conversations with Kristin and Jeff Smith, who helped me clarify my ideas.

For more background on this sort of narrative analysis, there’s a synoptic blog entry here. This earlier one might also be of use. Rory Kelly offers some nuanced analysis of the Hollywood character arc.

Cinema’s debts to theatre are considered in this entry, and some others in the category Film and other media. On the power of artisanal care, there’s this on Buster Scruggs.

Another entry discusses how actors use their faces in The Social Network.

P. S. 5 March 2021: I’ve just found some interesting remarks from Sorkin about what he calls “the puppy crate”–the need to focus a drama in a confined time and space. The Trial of the Chicago 7 is an obvious example, but so too is Steve Jobs. “I need four walls really badly.”

The Trial of the Chicago 7 (2020).

Vancouver: “It’s the Arts”

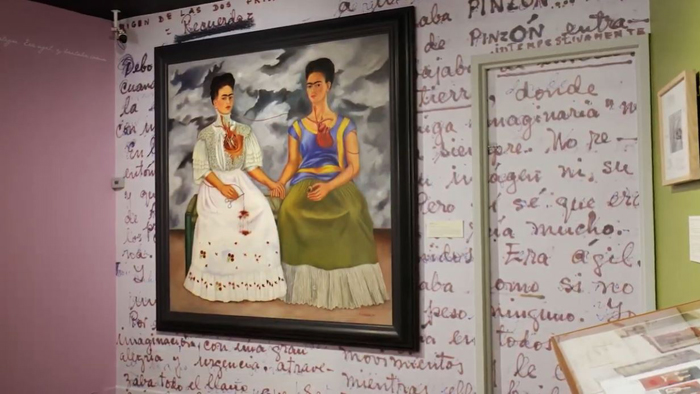

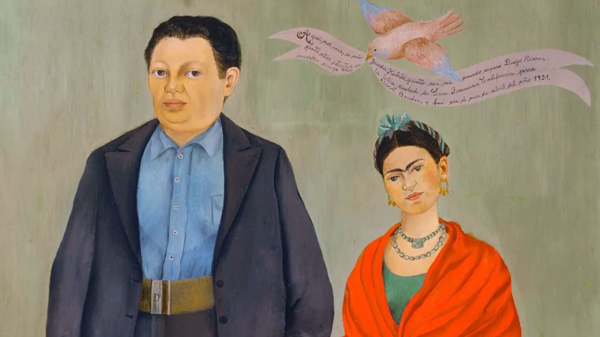

Frida Kahlo (2020)

Kristin here:

I wonder how many of my readers will recognize the source of this entry’s title. Is Monty Python’s Flying Circus still the perennial classic it was among young people for decades after its original series was broadcast? That brief sentence was the title of the sixth episode of the first season, shown in 1969, though I didn’t see it until some years later. The episode itself has little to do with the arts, but for some reason that particular title stuck with David and me, as few if any others did. Whenever we have encountered a TV program or a review, often something pretentious, one of us will turn to the other, or both simultaneously, and say, “It’s the Arts!”

The Vancouver International Film Festival has an admirable custom of showing many documentaries. They often deal with ecological issues and Canadian subject matter. One prominent thread, however, is documentaries about the arts. These are known as MAD, or “Music, Art and Design.” Although, as I mentioned in my previous entry, I tend to stick to the Panorama program of international fiction films, I always try to attend a few of these arts documentaries when they fit in with my interests. Most of these are in fact wonderful, not pretentious. Still, I am too accustomed to the phrase, and I think automatically, “It’s the Arts.”

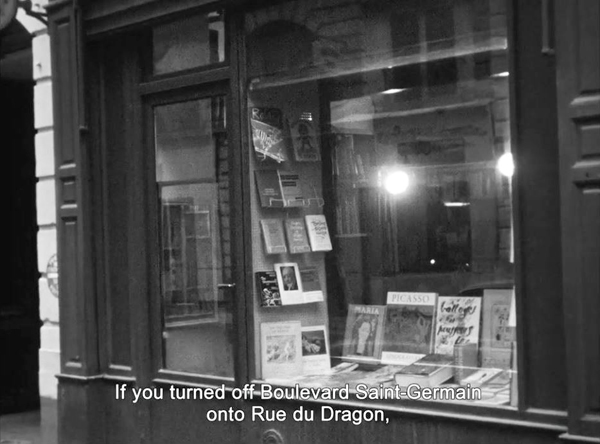

Paris Calligrammes (2019)